Chapter 7

Commercial TBML

TBML is generally considered to be a money-laundering methodology that is used to wash the proceeds of criminal activities such as narcotics trafficking, weapons smuggling, the trafficking of persons, and intellectual property rights violations. As we have discussed, TBML is also used in evading taxes and customs duties. TBML schemes are also sometimes used to circumvent restrictions on capital flows. Informal value transfer systems—a subset of TBML—such as hawala and fei-chien are also used.

Unfortunately, commercial enterprises also misuse trade in other suspect ways. International businesses and brokers engage in fraud and deceptive trade practices to obfuscate the money trail and transfer value for profit. Sometimes this takes the form of lowering taxes or claiming government trading incentives. The commercial misuse of trade goes hand-in-hand with the criminal misuse of trade. We cannot succeed in stopping criminals while we turn a blind eye to multinationals using misinvoicing and abusive transfer pricing as they choose. While commercial TBML is not the focus of this book, the reader should be aware of some common techniques such as trade diversion, misinvoicing, and transfer pricing. While some of the schemes may be generally accepted and legal per se, they often have the look and feel of their sister TBML scams.

Trade Diversion

In international economics and finance, there are various types and definitions of trade diversions. For the purpose of commercial trade-based value transfer, trade diversion is considered one of the more sophisticated forms of laundering large amounts of money.1 Like other forms of trade-based money laundering, commercial trade diversion often relies on hiding in plain sight; suspect or fraudulent transactions are disguised as legitimate, often using well-known firms to accomplish the transfer.

In trade diversion schemes, generally speaking, the conspirators take advantage of the fact that pricing differentials of goods can vary greatly from market to market and from country to country and are often based on narrow regulations and legislation in particular markets. In an international trade situation, a business or broker that offers a lower-cost product for importation into a particular country tends to create a trade diversion away from another importer or local producers whose prices are higher for a similar product.2 According to the late Donald deKieffer, an international trade attorney who studied trade diversion schemes, “The amount of people who are actually masters of the technique is fairly limited. These individuals, however, move millions of dollars every day in international commerce, largely undetected.”3

The “U-boat” commercial trade diversion scheme is popular in many international locations. Let's use the following hypothetical example where a buyer or a professional “diverter” directly or indirectly approaches a U.S. manufacturer and multinational corporation. Famous consumer brands such as Kraft, Johnson & Johnson, and Procter & Gamble have immediate brand recognition and are sought after around the world, so diverters often seek out these and other well-known companies. The diverters use a veneer of authenticity, often using shell companies and fronts to facilitate the transaction. The lack of transparency and beneficial owner information creates difficulties in later following the paper trail.

The broker/buyer/diverter presents a large and seemingly legitimate order. A sophisticated seller such as a large U.S. multinational will generally insist on an irrevocable letter of credit (L/C)—see Chapter 9. The conspirators in the scheme have relationships with financial institutions that can issue an L/C acceptable to the seller. When asked the destination of the product, the “buyer” most likely will indicate a legitimate market that is not served by the multinational manufacturer. The proposal might be presented in such a way as the buyer/broker will help the manufacturer “break into a new market.”

While there is nothing wrong with the above scenario, there are a few alarming possibilities:

- When the buyer/broker takes control of the goods, the shipment could be diverted to a proscribed destination or sold to a front that acts as a broker for a prohibited end-user such as Iran or North Korea.

- The goods could be diverted and sold back in the original country of origin—in the current example, the United States.

The first scenario is self-explanatory. The reason the second scheme is sometimes called U-boating is that upon purchase, the goods are frequently transshipped via an intermediary location. Rotterdam and Dubai are among the favored diversion locations. The containers are stripped, stuffed, and reloaded (in a manner similar to the method described in Chapter 2). The goods are then shipped right back to the country of origin. In the United States, taxes and tariffs are not paid to import the goods since customs law provides “duty-free treatment for U.S. goods returned.”5 (Many other countries have similar provisions.) A co-conspirator takes possession of the goods and they are sold and distributed at sometimes-steep discounts to prevailing prices. As a result, U.S. manufactured name-brand goods can sometimes be found in the U.S. black and gray markets and suspect distribution channels. They even surface in “big-box” discount stores.

The U-boat scheme requires an international network of conspirators. According to deKieffer, there are dozens of trading companies in Switzerland, Dubai, Singapore, the United Kingdom, and other locations that specialize in these types of transactions. Generally speaking, diversion purchases of the type described above are rarely less than $100,000 and often in the multimillions of dollars.6

Trade diversion can have disastrous effects when counterfeit goods are sometimes introduced into the equation. Particularly in the case of pharmaceuticals, it is very difficult to determine the difference between goods acquired in the gray market from those sold via legitimate trade. And illegal pharmaceuticals pose a potential safety hazard, as they often do not pass through a controlled and regulated supply chain. Even in the United States, a highly regulated and protected market, diverted pharmaceuticals have penetrated the supply chain.

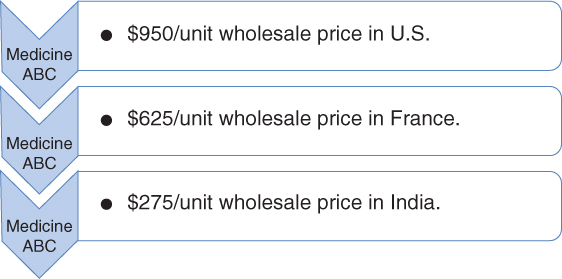

Using a hypothetical example of the sale of ABC medicine manufactured in the United States, per Figure 7.1 the selling price can vary dramatically in different markets. Yet it's the same medicine. This type of pricing arbitrage is unlike the fraudulent invoicing described in Chapter 2. Invoices are not used to launder money or transfer value in the form of a trade good, but rather product is diverted for profit.

Figure 7.1 Pricing arbitrage through diversion

The complex international supply chain for medicine provides a platform of opportunity for unscrupulous secondary wholesalers and traders to illegally divert product. Sometimes the medicine is passed through a wide array of other entities before reaching the end provider and patient or a bricks-and-mortar pharmacy.7 Two cases dramatically illustrate this type of commercial trade-based value transfer.

Example 1: Illegally Diverted Cancer Drug

An online pharmacy network based in Canada was investigated for its involvement in procuring illegally diverted pharmaceuticals. The Canadian company did not use best business practices and began to buy product in far-flung countries that drug safety experts say have lax regulation and problems with counterfeiting. In one case, purchase orders were made for Avastin—a lifesaving drug for some patients with cancer. The orders originated through a U.K. business, with a Barbados affiliate. Reportedly, the Barbados company owned or controlled some of the companies involved with the subsequent diversion.

Product was obtained through a Danish company, which in turn purchased the product from a licensed Swiss company. The cancer drug was originally ordered through an unlicensed Egyptian company, which obtained counterfeit drugs in Turkey using a Syrian broker.8 In the bastardized supply chain, some of the diverted and counterfeit Avastin ended up in the tightly controlled U.S. distribution network.

Example 2: HIV Drugs Destined for Africa Diverted to Europe

Drug maker GlaxoSmithKline participated in an HIV drug-discount program for developing countries. At the time, Combivar HIV anti-viral medication was selling for approximately $6 a pill in Western Europe. It was to be offered for sale at 80 cents a pill in sub-Sahara Africa.

Glaxo used airfreight companies to ship the medicine to Africa. However, once on the ground, the shipments were sent to multiple companies and then finally to an airfreight service employed by the diverters. In a type of U-turn transaction, the HIV drugs were then flown back to Europe and were introduced by middlemen into the regular supply chain for medicines. The African-destined version of Combivar was identical to the European version, thus mitigating scrutiny. The scheme was finally detected when customs inspectors in Belgium noticed irregularities in a shipment of HIV drugs sent from Senegal.9

Trade Misinvoicing

According to Raymond Baker, the head of Global Financial Integrity (GFI) and a worldwide authority on financial crime, “Trade misinvoicing—a prevalent form of trade based money laundering—accounts for nearly 80 percent of all illicit financial outflows that can be measured using available data.”10

The rapidly increasing volume of international trade exacerbates the situation. During my career with U.S. Customs, I observed first-hand the never-ending balancing act between efforts to promote commerce on the one hand against security and revenue concerns on the other. Because of the enormous pressures on customs services around the world to process commercial shipments as quickly as possible, trade misinvoicing is a comparatively low-risk endeavor for fraudsters—especially conspirators that only misrepresent their transactions by a moderate amount. If a buyer and seller do not get too greedy, their odds of getting caught are very slim.

So how do companies misinvoice trade goods? In many areas corruption and poor governance come into play, but according to GFI, legal gray areas and financial secrecy are the most important facilitators.11 An essential component of re-invoicing is sending profits offshore.

An excellent explanation of how the re-invoicing process works comes from GFI's Brian LeBlanc. I am quoting his imaginary example:13

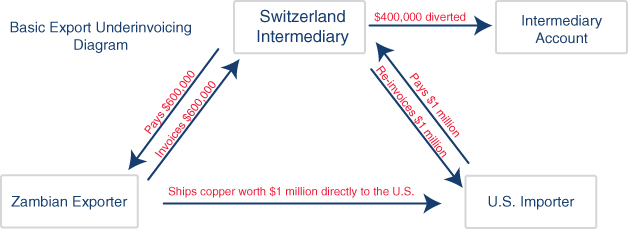

Let's assume the following scenario: imagine a hypothetical Zambian exporter of copper arranges a deal with a buyer in the United States worth $1,000,000. Now, let's assume that the Zambian company only wishes to report $600,000 to government officials to circumvent paying mining royalties and corporate income tax.

First, the Zambian exporter sets up a shell company in Switzerland, which (because of anonymity) cannot be traced back to him. By doing so, any transaction the Zambian exporter conducts with the shell company will look like trade with an unrelated party. Thus, even if the Zambian government suspects some wrongdoing, it will be very difficult, or impossible, to tie the Zambian exporter to the shell company in Switzerland.

Second, the exporter then uses the shell company to purchase the copper from the exporter in Zambia for a value of $600,000, $400,000 less than the true value of the copper. An invoice that shows receipt for the $600,000 copper sale is then forwarded on to Zambia tax collectors.

Third, the shell company in Switzerland then re-sells the copper to the ultimate buyer in the United States for the agreed-upon $1,000,000. The importer is instructed to make a payment to the shell company, and the goods are sent directly from Zambia to the United States without ever even passing through Switzerland.

Thus, the Zambian exporter lowered its taxable revenue from $1,000,000 to $600,000. The remaining $400,000 remains hidden in Switzerland where it is untaxed and unutilized for development purposes.

Figure 7.2 helps explain the process visually.

Figure 7.2 Basic export underinvoicing diagram14

Source: http://www.gfintegrity.org/press-release/trade-misinvoicing-or-how-to-steal-from-africa

Transfer Pricing

There is nothing illegal per se about transfer pricing. Transfer pricing is not used to launder criminal proceeds, but rather to lower taxes and increase profits. It is a fact of international commerce and occurs millions of times every day. However, abusive transfer pricing or the manipulation of the international trading system within the same multinational group to take advantage of lower jurisdictional tax rates represents enormous tax loss in the producing country. The magnitude of transfer pricing is difficult to determine but is believed to be in the hundreds of billions of dollars per year.15 Transfer pricing is found in both the developed and developing world but most dramatically affects poor countries, robbing them of needed revenue. According to tax expert Lee Sheppard of Tax Analysts, “Transfer pricing is the leading edge of what is wrong with international tax.”16

If two unrelated companies trade with each other across international boundaries, there is generally negotiation on price, resulting in a fair or market-driven charge. This is known as arm's-length trading and is considered acceptable for tax purposes. But if two companies jointly owned by a parent multinational group artificially distort the price of the recorded trade to minimize the tax bill, this becomes an issue of concern—particularly when the tax liability is shifted to a low-tax or tax-free haven.

The reader may recall during the explanation of TBML in Chapter 2, that when a buyer and seller are working together, the price of a good (or service) can be whatever the two parties want it to be. Although the above rule of thumb applied to TBML and illicit proceeds, the same applies to commercial transfer pricing.

So how does transfer pricing work?

Per Figure 7.3, Global Inc. is a hypothetical multinational headquartered in Canada. Tax Haven Inc., South Africa Inc., U.K. Inc., and Other Global partner companies are all subsidiaries of Global and part of the same multinational group.

Figure 7.3 Transfer pricing scheme

Global Inc. produces a variety of food products and wants to maximize its profit by lowering its tax rates. Per Figure 7.3, South Africa Inc. sells the product to Tax Haven Inc. at an artificially low price. This results in South Africa Inc. having low profits and the government of South Africa receiving little tax revenue. Then Tax Haven Inc. sells the product to U.K. Inc. at a very high price. The sale price per unit between the corporations is almost as high as the final retail price per unit offered for sale in the U.K. This results in U.K. Inc. having a very low tax bill and the U.K. government not receiving much revenue. In contrast, Tax Haven Inc. (part of the Global Inc. multinational family), bought the product at a very low price and sold it at very high price.

Tax Haven Inc.'s profits are enormous. But since it is in a tax haven jurisdiction, it has little tax liability. The end result is that Global Inc. artificially shifted its profits out of both South Africa and the United Kingdom and into a tax haven. Tax revenue was likewise shifted from South Africa and the United Kingdom and converted into higher profits for the multinational Global Inc.18 According to international trade expert Dr. John Zdanowicz, “It is not really necessary to move corporate headquarters to slash taxes and increase profits. What is necessary is to move taxable income.”19

The hemorrhage of needed tax revenue is enormous—particularly in the developing world. There are real societal losses connected to trade misinvoicing and transfer pricing. According to Global Financial Integrity, “For each $1 developing nations receive in foreign aid, $10 in illicit money flows abroad—facilitated by secrecy in the global financial system. Beyond bleeding the world's poorest economies, this propels crime, corruption, and tax evasion globally.”21

The human costs of commercial trade-based money and value transfer are the strongest arguments for international trade transparency and why this issue must be the next frontier in financial crimes enforcement.

Cheat Sheet

- Generally speaking, commercial TBML is not usually considered to be a vehicle used to launder illicit proceeds.

- Commercial TBML is widespread in international commerce and is used primarily to maximize profits and minimize taxes.

- Three prominent forms of commercial TBML are trade diversion, trade misinvoicing, and transfer pricing.

- Like other forms of TBML, commercial trade diversion often relies on hiding in plain sight.

- Participants in these schemes take advantage of the fact that pricing differentials of goods can vary greatly from market to market and from country to country and are often based on narrow regulations and legislation in particular markets. They rely on a type of arbitrage: buying goods cheaply and selling them dearly.

- Trade diversion is considered a gray-market activity. One of its most prominent forms is the U-boat scheme where genuine product is purchased at a very favorable price and is rerouted or diverted from its intended international market and “returned” to the country of production. There is generally no duty on returning goods. The goods are often resold on the black market or fraudulently into suspect distribution channels.

- An essential component of re-invoicing is sending profits offshore.

- Approximately 60 percent of international trade happens within multinationals—not between.

- If two unrelated companies trade with each other, there is generally negotiation on price. This results in a fair or market-driven charge. The process is known as arm's-length trading and is considered acceptable for tax purposes.

- If two or more companies jointly owned by a parent multinational group artificially distort the price of the recorded trade to minimize the tax bill, this becomes an issue of concern—particularly when the tax liability is shifted to a low-tax or tax-free haven. This is known as transfer pricing.