Chapter 2

Trade-Based Money Laundering Techniques: Invoice Fraud

In traditional money laundering involving the transfers of money, criminals seek to wash, launder, or legitimize illicit funds. Generally, they use a variety of techniques to first place dirty money in financial institutions in ways that do not trigger the financial transparency reporting requirements briefly described in Chapter 1. They next layer the money by frequently moving it between accounts or wiring it from bank to bank, often through multiple jurisdictions. Finally, criminal organizations integrate the laundered money back into the economy by purchasing real estate, businesses, investing in the stock market, and so on. The above three stages of money laundering are designed to make it difficult for investigators to follow the money trail. (See Appendix A for an overview of the three stages of money laundering.)

In TBML, criminals likewise seek to legitimize funds. They do so by genuinely or fraudulently buying and selling trade goods using a variety of techniques that very effectively transfer value in ways that sometimes bypass financial intelligence reporting requirements. Trade is also used in placement, layering, and integration.

In 2010, total global merchandise trade was approximately $31 trillion.1 The enormous size of global commerce increases the probability of TBML. Just like in traditional money laundering when criminals mix or comingle illicit money with licit money via financial institutions, the same holds true in international trade. The large volume of international commerce masks the occasional suspect transfer. It is the sheer magnitude and noise of global trade that presents the primary challenge to law enforcement and customs services around the world in their attempts to detect and counter TBML.

In addition to the massive trade volume and the mixing of the occasional illicit transaction with the overwhelming percentage of legitimate trade, there are other factors that combine to make it very difficult for authorities to monitor suspicious trade transactions:

- There are innumerable, complex types of trade finance deals found in the business world.

- Tax avoidance and capital flight generally involve the transfer of legitimate funds across borders, making it very difficult to distinguish intent.

- Underground financial systems that rely heavily on trade are, by their very nature, nontransparent.

- At all levels of industry and government, there is limited understanding and resources to detect suspicious trade transactions.

- Criminals, fraudsters, and tax cheats use a variety of techniques and schemes in the misuse of trade.

- Corruption is the great facilitator in many forms of TBML.

TBML is generally considered a complex money-laundering methodology. Its components cut across sectorial boundaries and national borders. To distinguish TBML and value transfer from the legitimate activities of international trade is sometimes quite difficult. And TBML is often combined with other common money-laundering techniques, such as the layering of financial transactions, the use of offshore shell companies, the use of bulk cash, and various underground financial systems.

How Does TBML Work?

In its primary form, TBML revolves around invoice fraud and associated manipulation of supporting documents. When a buyer and seller work together, the price of goods (or services) can be whatever the parties want it to be. There is no invoice police! As Raymond Baker—one of the world's foremost experts in financial crimes—succinctly notes, “Anything that can be priced can be mispriced. False pricing is done every day, in every country, on a large percentage of import and export transactions. This is the most commonly used technique for generating and transferring dirty money.”2

The primary techniques used for invoice fraud and manipulation are:3

- Over- and underinvoicing and shipments of goods and services

- Multiple invoicing of goods and services

- Falsely described goods and services

Other common techniques related to the above include:

- Short shipping: This occurs when the exporter ships fewer goods than the invoiced quantity of goods, thus misrepresenting the true value of the goods in the documentation. The effect of this technique is similar to overinvoicing.

- Overshipping: The exporter ships more goods than what is invoiced, thus misrepresenting the true value of the goods in the documentation. The effect is similar to underinvoicing.

- Phantom shipping: No goods are actually shipped. The fraudulent documentation generated is used to justify payment abroad.

Invoice Fraud

Money laundering and value transfer through the over- and under-invoicing of goods and services is a common practice around the world. The key element of this technique is the misrepresentation of trade goods to transfer value between the importer and exporter or settle debts/balance accounts between the trading parties. The shipment (real or fictitious) of goods and the accompanying documentation provide cover for the transfer of money.

First, by underinvoicing goods below their fair market price, an exporter is able to transfer value to an importer while avoiding the scrutiny associated with more direct forms of money transfer. The value the importer receives when selling (directly or indirectly) the goods on the open market is considerably greater than the amount he or she paid the exporter.

For example, Company A located in the United States ships one million widgets worth $2 each to Company B based in Mexico. On the invoice, however, Company A lists the widgets at a price of only $1 each, and the Mexican importer pays the U.S. exporter only $1 million for them. Thus, extra value has been transferred to Mexico, where the importer can sell (directly or indirectly) the widgets on the open market for a total of $2 million. The Mexican company then has several options: it can keep the profits; transfer some of them to a bank account outside the country where the proceeds can be further laundered via layering and integration; share the proceeds with the U.S. exporter (depending on the nature of their relationship); or even transfer them to a criminal organization that may be the power behind the business transactions.

To transfer value in the opposite direction, an exporter can overinvoice goods above their fair market price. In this manner, the exporter receives value from the importer because the latter's payment is higher than the goods' actual value on the open market.

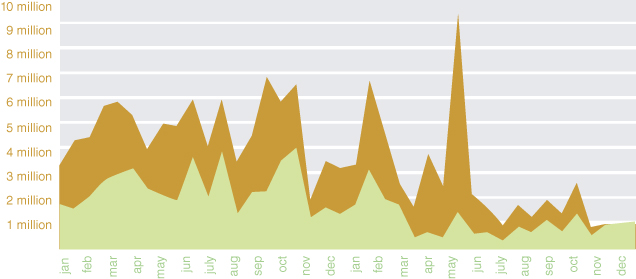

For example, Figure 2.1 shows the fluctuating value associated with thousands of refrigerators exported from Country A to Country B via a series of shipments. The darker shade represents the declared value of the refrigerators upon export from Country A, and the light shade represents their declared value upon arrival in Country B. The horizontal line represents the time period over which these shipments occurred. The vertical line represents the value expressed in dollars. In this case, the refrigerators were overinvoiced. The export data came from the “shippers export declaration” (SED) that accompanies the shipments. The import data came from the importing country's customs service. Obviously, the declared export price should match the declared import price. (There are some recognized but comparatively small pricing variables. In addition, the quantity and quality of refrigerators should also match—which occurred in this case.) The difference in price between the dark and light shades represents the transfer of value from the importer to the exporter. In this case, the transfer actually represented the proceeds of narcotics trafficking.

Figure 2.1 Comparative imports and exports of refrigerators4

Copyright © 2012. SAS Institute Inc. All rights reserved. Reproduced with permission of SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA. From http://www.sas.com/news/sascom/terrorist-financing.html.

The reader can see at the end of the chart the shaded colors start to converge. The colors or values between imports and exports begin to match because data were compared, anomalies noted, and joint enforcement action taken by the two countries involved. Trade transparency was achieved. The comparative stability at the end of the chart reflects true market conditions.

Table 2.1 lists genuine examples of abnormal prices of trade goods entering and departing the United States. The information is from a study conducted by Dr. John Zdanowicz analyzing U.S. trade data. For example, plastic buckets from the Czech Republic are imported with the declared price of $972 per bucket! Toilet tissue from China is imported at the price of over $4,000 per kilogram. The second column lists low U.S. export prices; for example, bulldozers are being shipped to Colombia at $1.74 each! As we will see, there are various reasons why the prices could be abnormal. For example, there could simply be a data “input” or “classification” error. However, recalling the above explanation of over- and underinvoicing, the abnormal prices could also represent attempts to transfer value in or out of the United States in the form of trade goods. At the very least, the prices should be considered suspicious. Only analysis and investigation will reveal the true reasons for such large discrepancies between market price and declared price.

| High U.S. Import Prices | Low U.S. Export Prices |

| Plastic buckets from Czech. Rep. $972/unit |

Live cattle to Mexico $20.65/unit |

| Briefs and panties from Hungary $739/dozen |

Radial truck tires to the United Kingdom $11.74/unit |

| Cotton dishtowels from Pakistan $153/unit |

Toilet bowls to Hong Kong $1.75/unit |

| Ceramic tiles from Italy $4,480 sq. meter |

Bulldozers to Colombia $1.74/unit |

| Razors from the United Kingdom $113/unit |

Missile launchers to Israel $52.03/unit |

| Iron bolts from France $3,067/kg |

Prefab buildings to Trinidad $1.20/unit |

| Toilet tissue from China $4,121/kg |

Forklift trucks to Jamaica $384.14/unit |

I once investigated an international criminal network involved in the transshipment of garments and textiles into the commerce of the United States in violation of quota laws. The conspiracy involved an international network of brokers and manufacturers. They were involved in trading tens of millions of dollars' worth of garments. The garments were manufactured in China and India but the country-of-origin labels on the garments and accompanying documentation made it appear that they actually originated in countries located in the Middle East and East Africa. Working with an industry source, I obtained information on this transnational fraud scheme including the recovery of a document, which was the proverbial “smoking gun.”

The document was sent from the primary suspect, a Dubai-based trade broker, to a garment manufacturer in the Middle East, his co-conspirator in the transshipment scheme. The document advertised the conspirators' trade-based laundering services, including “reexport charges,” “relabeling charges,” and fees for “unstuffing and reloading containers.” The freight forwarder also listed charges for creating bills of lading, customs duties, port fees, and document-handling fees. A notation on the document also stated, “Suggest you send us some blank invoices on company letterhead.” With fraudulent invoices and supporting documentation, conspirators on opposite sides of the world commit customs fraud at a minimum. They can also transfer value in the form of trade goods. Unfortunately, there is little risk of detection.

Another technique used to transfer money under the guise of trade is to issue multiple invoices for the same international trade transaction. This is done to justify multiple payments for the same shipment of goods. Although fictitious pricing can be involved, unlike the over- and underinvoicing, there is no need for the importer or the exporter to misrepresent the price of the good on the commercial invoice. And to add further complexity to the scheme, sometimes the fraudsters use different financial institutions to make payments.

For example, as part of the analysis into the laundering of a massive amount of proceeds from narcotics sales in the United States as part of Operation Polar Cap (see below), I investigated gold dealers in Europe and the Middle East. They issued multiple invoices for the same shipment of gold. The invoices facilitated the international payment of laundered drug money from accounts in the United States.

Suspect actors involved in TBML and other types of financial fraud may keep false sets of books. I once conducted a joint investigation in Italy with the Italian Guardia di Finanza (GdF), or fiscal police. The suspect was engaged in TBML via the fraudulent invoicing of shipments of gold jewelry from Italy to the United States. The investigation was a spinoff of Operation Polar Cap. The analysis of business records included GdF search warrants served at the subject's business and residence. At the business, they found a set of fictitious business records, including fraudulent invoices. This was the set of books the suspect kept to show the authorities. In the simultaneous search of the suspect's residence, they found the true set of books.

On another occasion, I was in the Middle East conducting a fraud investigation. Once again, fictitious invoicing was involved. During the course of the investigation, copies of the invoices and the supporting shipping documents were obtained. When the investigation was complete, I interviewed the subject in the presence of the local authorities. If the document said one thing, the suspect said another. Finally, when I proved to the suspect that the documents he originated and that we had in front of us were fraudulent, instead of staying quiet or admitting guilt, he offered to get another set of documents within a few hours. They would magically have the correct numbers, signature, amount, certifications, and so on! Thus, because TBML is fraudulent by its very nature, it often involves multiple sets of books and rampant document fraud.

Case Examples: Invoice Fraud and Manipulation

The best way to understand the variety of the techniques involved with invoice fraud and how it is related to TBML and value transfer is to examine genuine case examples. The following cases originated in diverse locations. Some are recent and some dated. However, even the older cases are exemplary of current schemes. (In my professional experience, criminal organizations continue to use the same methodologies and techniques until there is some sort of successful enforcement action.) In some instances, the identifying information has been omitted or changed. A few of the examples are rather straightforward and deal with some of the techniques already described. Some cases illustrate combinations of money-laundering techniques and are more complex. Case examples involving underground financial systems and other forms of TBML will be included in later chapters.

Case Study 1: False Invoicing Polypropylene Pellets

A narcotics trafficking and money laundering network inflated the value on high-volume shipments of polypropylene pellets exported from the United States to Mexico. Polypropylene is used to make a variety of plastic articles. Eventually, the operation caught the attention of bank compliance officers and they discontinued letters of credit used by the suspected launderers. Law enforcement investigated the network. It is believed the operation was hiding approximately $1 million every three weeks. One individual involved said, “You generate all of this paperwork on both sides of the border showing that the product you're importing has this much value on it, when in reality you paid less for it. Now you've got paper earnings of a million dollars. You didn't really earn that, but it gives you a piece of paper to take to [Mexican authorities] to say: “These million dollars in my bank account—it's legitimate. It came from here, see?”8

Case Study 2: Inflated Invoices and Terror Finance

According to Pakistani officials, a madrassa—a fundamental Islamic religious school—was linked to radical jihadist groups. The madrassa received large amounts of money from foreign sources. It was engaged in a side business dealing in animal hides. In order to justify the large inflow of funds, the madrassa claimed to sell a large number of hides at grossly inflated prices. This ruse allowed the extremists to “legitimize” the inflow of funds, which were then passed to terrorists.9

Case Study 3: TBML and Export Incentives

A network of co-conspirators based in Argentina engaged in both TBML and fraud against the Argentine government. The conspirators created a company in New Jersey called “Molds, Dies, and Novelties” that imported goods from an Argentine company the conspirators controlled called “Casa Piana.” Over a multiyear period, the Argentines exported gold-plated copper medallions worth approximately $95 million. However, the conspirators prepared fraudulent export documentation for Argentine customs showing that the value of the goods was far greater. The medallions were flown from Buenos Aires to New York's JFK International Airport and imported into the United States. In addition to the medallions, Casa Piana also sent fraudulently described “solid gold” coins that were only coated with gold. They were overinvoiced. The scam enabled the conspirators to collect export incentives for the “locally manufactured” goods.

Many countries offer generous tax incentives to domestic manufacturers for selling their goods and services abroad. And criminals sometimes abuse these tax incentives by overreporting their exports. So in addition to engaging in TBML and value transfer through overinvoicing the coins, the government of Argentina awarded the conspirators approximately $130 million in export incentives!10

Case Study 4: Vehicles, TBML, and Terror Finance

From approximately 2007 to 2011, at least $329 million was transferred by wire from the Lebanese Canadian Bank, the Hassan Ayash Exchange Company, the Ellissa Exchange Company, and other Lebanese financial institutions to the United States for the purchase and shipment of used cars. Allegedly, some of the money involved was from the proceeds of narcotics trafficking. According to investigators, the car buyers in the United States typically had little or no property or assets other than the bank accounts used to receive the overseas wire transfers. After purchase, the cars were primarily shipped to Cotonou, Benin, where they were housed and sold from large car parks. See Figure 2.2.

Figure 2.2 Export of used cars from the United States

Source: http://www.fatf-gafi.org/media/fatf/documents/reports/Trade_Based_ML_APGReport.pdf, p. 57.11

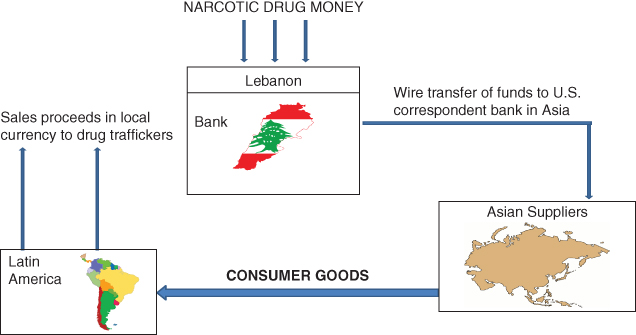

The money exchanges in this scheme were involved with various TBML techniques, including the misinvoicing of automobiles and consumer goods from Asia. The primary suspect, based in Asia, owned a wide network of companies dealing in numerous products. The suspect based his banking operations in Lebanon. The suspect received funds in his accounts from a Latin American drug kingpin. Proceeds generated in local currency from the sale of the imported consumer goods were deposited in individuals' accounts in the local banks. Per Chapter 3's explanation of the Black Market Peso Exchange, this allowed for the repatriation of narcotics proceeds for the Latin American drug producers.12 See Figure 2.3. The exchanges also used their foreign money transmitter businesses to process millions of dollars on behalf of narcotics traffickers and money launderers. They attempted to hide the source of the funds by comingling and layering the transactions across a variety of international businesses and financial accounts.13

Figure 2.3 Purchase of consumer goods14

Source: http://www.fatf-gafi.org/media/fatf/documents/reports/Trade_Based_ML_APGReport.pdf, p. 58.

A significant portion of the cash proceeds from the car sales was transported to Lebanon by a Hezbollah-controlled system of money couriers, cash smugglers, hawaladars (see Chapter 4), and currency brokers. A network of money couriers controlled by Oussama Salhab, an alleged Hezbollah operative living in Togo, transported tens of millions of dollars and euros from Benin to Lebanon through Togo and Ghana. Salhab and his relatives also controlled a transportation company based in Michigan that was frequently used to ship cars to West Africa, as well as other entities involved in the scheme. Cash transported from West Africa was often routed through the Beirut airport, where Hezbollah security safeguarded its passage to its final destination.15

Case Study 5: TBML and Iranian Sanctions

Because of sanctions, much of Iran's foreign currency has been locked in overseas escrow accounts. The Iranian regime could only use local currency to buy local products. Front companies in Turkey were conduits for Iranian attempts to access the frozen funds. Turkish front companies issued fraudulent invoices for transactions for goods such as food and medicine that were permitted to be shipped to Iran under humanitarian grounds. For example, a Turkish prosecutor's report details a 2013 invoice involving a Turkish luxury yacht company selling nearly 5.2 tons of brown sugar to Iran's Bank Pasargad, with delivery to Dubai. Turkey's state-owned Halkbank facilitated the transaction. The sugar was invoiced at the price of 1,170 Turkish liras per kilo or approximately $240 per pound!16

Case Study 6: Teddy Bears Used to Launder Drug Money

Angel Toy Corporation based in Los Angeles received a large amount of illicit cash generated from a narcotic trafficking organization based in Colombia. In some cases, couriers affiliated with the drug traffickers dropped off the cash at the toy company's store in Los Angeles. In other cases, cash deposits were made directly into the company's bank account, sometimes by individuals located as far away as New York. During the four-year investigation, more than $8 million in cash deposits were traced into Angel Toy Corporation's accounts; not a single transaction was over the $10,000 currency transaction report (CTR) reporting threshold.

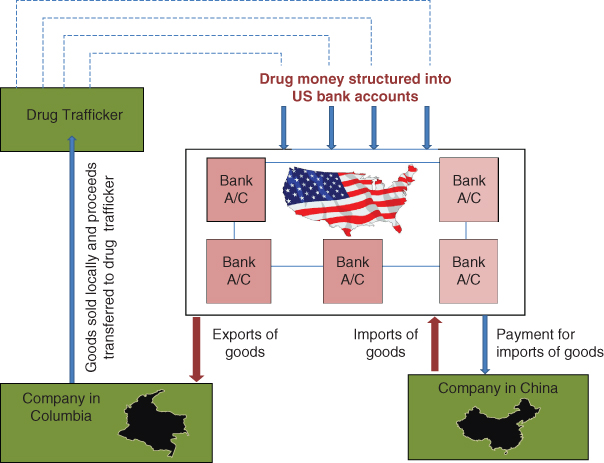

Bank accounts of the toy company were used to pay for the import of toys manufactured in China, including teddy bears. Once the toys arrived in the United States, they were exported from Angel Toy Corporation to another toy company in Colombia. Pesos generated by the sales of toys by the Colombian toy company were used to reimburse the Colombian drug trafficker. Five persons, including two owners of Angel Toy Company, were convicted and fined.17 See Figure 2.4. The Angel Toy Company case is representative of value transfer techniques, including the Colombian black market peso exchange. (See Chapter 3.)

Figure 2.4 Toy company involved with TBML18

Source: http://www.fatf-gafi.org/media/fatf/documents/reports/Trade_Based_ML_APGReport.pdf, p. 63.

Case Study 7: Brazilian Paralelo

An investigation of an unlicensed money services business (MSB) in Atlanta resulted in the seizure of substantial funds from several bank accounts. The subsequent investigation revealed that a black market currency exchanger in Brazil, called a doleiro, was transferring payments to U.S. bank accounts. The owner of the U.S. accounts would then facilitate third-party wire transfers to U.S. and Asian exporters for commercial goods that were shipped to the South American triborder area of Brazil, Argentina, and Paraguay. In Brazil, this kind of TBML scheme is known as the paralelo. It is designed to avoid high fees and taxes associated with legitimate international wire transactions conducted via the National Bank of Brazil. Criminal organizations use trade-based value to disguise the illicit origins of criminal proceeds. Analysis and investigation documented the illegal transfer of more than $100 million from the triborder area to the United States.19

Case Study 8: South Korean Uses Invoice Fraud to Circumvent Iranian Sanctions

According to U.S. State Department reporting, “In 2013, South Korean prosecutors detained and charged a Korean American with the illegal transfer of approximately $1 billion in restricted Iranian money frozen in South Korea pursuant to U.S. and international sanctions. The individual is suspected of making fraudulent transfers in 2011 from the Iranian central bank's won-denominated account at a South Korean bank by using fictitious invoices for payment. The scale and volume of the laundering operation demonstrate the vulnerabilities associated with not fully applying sufficient AML/CFT controls to high-risk customers and jurisdictions.”20

Cheat Sheet

- In TBML, criminals also try to place, layer, and integrate illicit funds. They do so by genuinely or fraudulently buying and selling trade goods using a variety of techniques that very effectively transfer value in ways that sometimes bypass financial intelligence reporting requirements.

- The volume of global merchandise trade (approximately $31 trillion in 2010) increases the probability of TBML.

- The misuse of international trade is also found in tax evasion, transfer pricing, capital flight, customs fraud, commercial fraud, underground financial systems, and various criminal schemes.

- Invoice fraud is the most frequently used form of TBML.

- The key element of TBML is the misrepresentation of a trade good in order to transfer additional value or settle debts between an importer and an exporter.

- The three most common techniques involved with invoice fraud are over- and underinvoicing, multiple invoicing, and falsely described goods.

- The amount shown on an invoice can be whatever the buyer and seller agree upon. “Whatever can be priced can be mispriced.”

- Payment for the goods provides cover for the movement of illicit money.

- Illicit actors may create false sets of books and accounting records to match their fraudulent invoices.

- Other documentation used in trade, such as fraudulent bills of lading, are also used to support TBML schemes.

Questions to Ask if a Shipment of Goods Looks Suspicious

Questions and observations will vary greatly, depending on the position of the questioner, that is, whether the interviewer works in a financial institution and is involved in trade finance, or perhaps has a position in customs, law enforcement, and so on. A comprehensive list of red-flag indicators is included in Chapter 10.

- What are the items being shipped?

- Where are they manufactured or produced?

- What is the ultimate destination?

- Is the routing logical?

- Is the origin and destination logical or suspect?

- Who is the buyer and who is the seller?

- Who benefits most from the transaction as it appears on paper? (Investigators should direct most of their attention at this party.)

- If one of the parties is obviously losing money on the transaction, investigators should question how they are still in business.

- Who is the shipper, broker, and/or freight forwarder? What is the relationship to the buyer/seller?

- Is this a regularly scheduled shipment of goods?

- Does the content of the shipment match the business of the parties involved with the transaction?

- Are there accompanying documents available? If so, what kind? If possible, request copies of all documents.

- Does the content and cost of the shipment match the description in the accompanying documents?

- Is the price of the goods in question standard market value? (There will be many variables involved in determining price.)

- Are the size, weight, and packaging consistent with the contents?

- What kind of payment is involved (e.g., cash, letter of credit, direct wire transfer, barter, etc.)?

- What financial institutions are involved?

- Is there an extraordinary business relationship between the parties involved (buyer, seller, freight forwarder, brokers, etc.)? Are they part of an identifiable group, network, or family?

- Are the parties involved reputable? Have they been engaged in previous verifiable business?

- If applicable, is there any law enforcement, financial intelligence, internal, or publicly available derogatory information on any of the parties involved?