Chapter 1

The Next Frontier

The Financial Action Task Force (FATF) has declared that there are three broad categories for the purpose of hiding illicit funds and introducing them into the formal economy. The first is via the use of financial institutions; the second is to physically smuggle bulk cash from one country or jurisdiction to another; and the third is the transfer of goods via trade.1 The United States and the international community have devoted attention, countermeasures, and resources to the first two categories. Money laundering via trade has, for the most part, been ignored.

The United States' current anti–money laundering efforts began in 1971, when President Nixon declared the “war on drugs.” About the same time, Congress started passing a series of laws, rules, and enabling regulations collectively known as the Bank Secrecy Act (BSA). The BSA is a misnomer. The goal is financial transparency by mandating financial intelligence or a paper trail to help criminal investigators “follow the money.” Today, primarily as a result of the BSA, approximately 17 million pieces of financial intelligence are filed with the U.S. Treasury Department's Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) every year. The financial intelligence is warehoused, analyzed, and disseminated to law enforcement agencies at the federal, state, local, and increasingly the international levels.

The worldwide community slowly followed the U.S. lead. In 1989, the G-7 created the FATF. The international anti–money laundering policy-making body championed 40 recommendations for countries and jurisdictions around the world aimed at the establishment of anti–money laundering (AML), and after September 11, counterterrorist financing (CFT) countermeasures. These included the passage of AML/CFT laws, the creation of financial intelligence, know your customer (KYC) compliance programs for financial institutions and money services businesses, the creation of financial intelligence units (FIUs), procedures to combat bulk cash smuggling, and other safeguards.

The FATF's initial recommendations were purposefully imprecise in order to accommodate different legal systems and institutional environments. In its infancy, the FATF was also Western centric, focusing on money laundering primarily through the prism of the West's “war on drugs,” where large amounts of dirty money were found sloshing around Western-style financial institutions. The FATF and its members almost completely ignored other forms of non-Western money laundering. Unfortunately, the FATF's early myopia had serious repercussions. Terrorist groups and criminal organizations continue to take advantage of what Osama bin Laden once called “cracks” in the Western financial system.2

As FATF evolved and the international community responded to growing financial threats, including the finance of terror, its nonbinding recommendations became increasingly precise. Its recommendations and interpretive notes have undergone periodic updates. In 1996, 2003, and 2012, its standards were significantly revised. The FATF's membership expanded, and today FATF-style regional bodies are found around the world.

Yet outside of FATF's 2006 trade-based money laundering “typology” report and similar studies conducted by FATF-style regional bodies (a study of particular note was conducted by the Asia Pacific Group in 2012), trade-based money laundering and value transfer have, for the most part, been ignored by the international community. This despite the FATF's above declaration that trade is one of the three principal categories of laundering money found around the world. For a variety of reasons, it has not been possible to achieve consensus on the extent of the problem and what should be done to confront it. And there continues to be an ongoing debate about whether financial institutions have the means and should assume the responsibility to help monitor international trade and trade finance as it relates to money laundering.

In 2014, The Economist called trade “the weakest link” in the fight against dirty money.3 I agree with the assessment but believe it will change. Governments around the world—simultaneously pressed for new revenue streams and threatened by organized crime's use of money laundering, corruption, massive trade fraud, transfer pricing, and the associated threat of terror finance—are slowly moving to recognize the threat posed by trade-based money laundering and value transfer. (Note: TBML will be used in this book as the accepted acronym.)

The key word in the above definition is value.4 To understand TBML, we must put aside our linear Western thought process. Illicit money is not always represented by cash, checks, or electronic data in a wire transfer, or new payment methods such as stored-value cards, cell phones, or cyber-currency. The value represented by trade goods—and the accompanying documentation both genuine and fictitious—can also represent the transfer of illicit funds and value. This book will provide many examples of the how and why.

The Magnitude of the Problem

To estimate the amount of TBML in the United States and around the world, we must first examine the magnitude of international money laundering in general. Those estimates are all over the map. In fact, the FATF has stated, “Due to the illegal nature of the transactions, precise statistics are not available, and it is therefore impossible to produce a definitive estimate of the amount of money that is globally laundered every year.”5

However, the International Monetary Fund has estimated that money laundering comprises approximately 2 to 5 percent of the world's gross domestic product (GDP)6 or approximately $3 trillion to $5 trillion per year. In very rough numbers, that is about the size of the U.S. federal budget! The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) conducted a study to determine the magnitude of illicit funds and estimates that in 2009, criminal proceeds amounted to 3.6 percent of global GDP, or approximately $1.6 trillion being laundered.7 So how much of that involves TBML? The issue has never been systematically examined. However, I will use a few metrics to put things in context.

According to the U.S. Department of State's 2009 International Narcotics Control Strategy Report (INCSR), it is estimated that the annual dollar amount laundered through trade ranges into the hundreds of billions.8 In fact, the State Department has concluded that TBML has reached “staggering” proportions in recent years.9

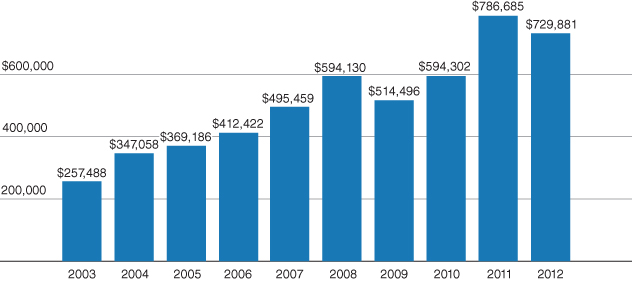

Global Financial Integrity (GFI), a Washington, D.C.–based nonprofit, has done considerable work in examining trade-misinvoicing. It is a method for moving money illicitly across borders, which involves deliberately misreporting the value of a commercial transaction on an invoice and other documents submitted to customs (see Chapter 7). A form of trade-based money laundering, trade-misinvoicing is the largest component of illicit financial outflows measured by GFI. After examining trade data covering developing countries, GFI concluded that a record $991.2 billion was siphoned from those countries in 2012 via trade misinvoicing!10 In its 2014 study, GFI finds that the developing world lost $6.6 trillion in illicit financial flows from 2003 to 2012, with illicit outflows alarmingly increasing at an average rate of more than approximately 9.4 percent per year.11 See the illustration in Figure 1.1 for the 2002–2012 trade-misinvoicing outflows. Of course, much of this hemorrhage of capital originates from crime, corruption, fraud, and tax evasion.

Figure 1.1 Trade-misinvoicing outflows from developing countries 2003–201212 (in millions of dollars, nominal)

Source: Global Financial Integrity, http://www.gfintegrity.org/issue/trade-misinvoicing/ (2015).

In the United States, the UNODC estimated proceeds from all forms of financial crime, excluding tax evasion, was $300 billion in 2010, or about 2 percent of the U.S. economy.13 This number is comparable to U.S. estimates.14

There are no reliable official estimates on the magnitude of TBML as a whole. Since the issue affects national security, law enforcement, and the collection of national revenue, it is remarkable that the U.S. government has never adequately examined TBML.

Dr. John Zdanowicz, an academic and early pioneer in the field of TBML, examined 2013 U.S. trade data obtained from the U.S. Census Bureau. Using methodologies explained further in Chapters 2 and 9, by examining undervalued exports ($124,116,420,714) and overvalued imports ($94,796,135,280), Dr. Zdanowicz found that $218,912,555,994 was moved out of the United States in the form of value transfer! That figure represents 5.69 percent of U.S. trade. Examining overvalued exports ($68,332,594,940) and undervalued imports ($272,753,571,621), Dr. Zdanowicz calculates that $341,086,166,561 was moved into the United States! That figure represents 8.87 percent of U.S. trade in 2013.15

A further complicating factor in estimating the magnitude of TBML involves the factoring of predicate offenses or “specified unlawful activities” involved. Predicate offenses are crimes that underlie money laundering or terrorist finance activity. Years ago, drug-related offenses were considered as the primary predicate offenses for money laundering. Over time, the concept of money laundering has become much more inclusive. Today, the United States recognizes hundreds of predicate offenses to charge money laundering, including fraud, smuggling, and human trafficking. The international standard is “all serious crimes.” This is an increasingly important consideration, because in many international jurisdictions, tax evasion is also a predicate offense to charge money laundering. This viewpoint is gaining traction around the world.

Returning to the estimates of the overall magnitude of global money laundering, experts believe approximately half of the trillions of dollars laundered every year represent traditional predicate offenses, such as narcotics trafficking. The other half comes from tax-evading components.16 In 2012, the FATF revised its recommendations to require that tax crimes and smuggling (which includes non-payment of customs duties) be included as predicate offenses for money laundering. The Internal Revenue Service believes, “Money laundering is in effect tax evasion in progress.”17 In the United States, customs violations including trade fraud is the most important predicate offense involved with TBML.18 Other primary predicate offenses worldwide for TBML include tax evasion, commercial fraud, intellectual property rights violations, narcotics trafficking, human trafficking, terrorist financing, embezzlement, corruption, and organized crime (racketeering).19

The misuse of trade is also involved with capital flight, or the transfer of wealth offshore, which can be very harmful to countries with weak economies. Although many governments have passed laws governing how much currency can be removed from their jurisdiction and what types of overseas investments their citizens can make, individuals and businesses have sometimes been able to circumvent these controls by sending value in the form of trade goods and payment offshore. This was a common tactic during the apartheid era of South Africa and is being done today by wealthy Venezuelans, Pakistanis, Russians, Iranians, Chinese (see Chapter 5), and many others. For example, much private wealth in Iran is also transferred out of the country via hawala. Dubai is a favored destination. As we will see later in this book, in the regional hawala networks, trade is the favored network to provide countervaluation between brokers. Wealth is also being siphoned via various forms of commercial trade–based money laundering, such as misinvoicing and transfer pricing. And, of course, trade-based value transfer is often an integral component in various forms of corruption, such as concealing illegal commissions.

Another way of looking at TBML from the macro level is to examine global merchandise trade, which is only the trade in goods, not services or capital transfers or foreign investments. We will discuss it in more detail in the next chapter. Global merchandise trade is in the multiple of tens of trillions of dollars every year. For illustrative purposes, if only 5 percent of global merchandise trade is questionable or somehow related to the multiple forms of TBML discussed in this book, we are talking about well over one trillion dollars a year in tainted money and value!

So if we factor tax evasion, including customs fraud, into the TBML equation, as well as capital flight, forms of informal value transfer systems as described in Chapters 3, 4, and 5, and commercial TBML such as trade misinvoicing as described in Chapter 7, the magnitude is enormous. It could very well be the largest money laundering methodology in the world! And, unfortunately, it is also the least understood and recognized.

How Are We Doing?

Once again, it is necessary to first look at our success/failure rate versus global money laundering as a whole. Reliable statistics are hard to find and sometimes dated. Yet the data that do exist present a bleak picture. It important to remember that in anti–money laundering efforts, the bottom-line measurables (a term used frequently within the U.S. government) are not the number of suspicious transaction reports filed (SARs) or the politically popular but vague term of disruption. Rather, the metrics that matter are the number of arrests, convictions, and illicit money identified, seized, and forfeited. Despite periodic positive public pronouncements from the Department of Treasury and various administrations, here are a few sobering numbers:

- According to the United Nations Office of Drug Control (UNODC), less than 1 percent of global illicit financial flows are currently being seized and frozen.20

- Per data collected by the Office of the U.S. National Drug Control Policy, Americans spend approximately $65 billion per year on illegal drugs. According to the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), only about $1 billion is seized.21

- According to Raymond Baker, a longtime authority on financial crimes, using statistics provided by U.S. Treasury Department officials concerning the amount of dirty money coming into the United States and the portion caught by anti–money laundering enforcement efforts, the numbers show enforcement is successful 0.1 percent of the time and fails 99.9 percent of the time. “In other words, total failure is just a decimal point away.”22

- Information suggests that in the United States, money launderers face a less than 5 percent risk of conviction.23 And according to the U.S. State Department,24 buttressed by my personal observations, the situation in most areas of the world is even worse.

Trying to narrow the numbers down to cover TBML is even more difficult. Statistics on the detection of TBML are very limited, and most international jurisdictions do not distinguish TBML from other forms of money laundering. Moreover, in most countries, trade data are collected by customs. Their mandate is primarily the collection of revenue via the collection of taxes, fines, and penalties. Thus, many customs services do not have the legal directive to take enforcement action, nor the training or competence to combat TBML.25

So considering that experts believe TBML is one of the three largest money laundering categories, it is found around the world, and simultaneously, it is one of the most opaque, least-known and understood, and most underenforced money laundering techniques, we are not doing very well at all.

Moreover, according to the U.S. Department of Treasury, TBML has a “more destructive impact on legitimate commerce than other money laundering schemes.”26 Trade fraud puts legitimate businesses at a competitive disadvantage, creating a barrier to entrepreneurship, and crowding out legitimate economic activity. TBML often robs governments of tax revenue due to the sale of underpriced goods, and reduced duties collected on undervalued imports and fraudulent cargo manifests.27 Commercial TBML causes massive societal losses— particularly in the developing world.

Simply put, TBML is the “next frontier” in international money laundering enforcement.