Chapter 4

Hawala: An Alternative Remittance System

There are an estimated 232 million migrant workers around the world.1 Globalization, demographic shifts, regional conflicts, income disparities, and the instinctive search for a better life continue to encourage ever-more workers to cross borders in search of jobs and security.

Many countries are dependent on remittances as an economic lifeline. The World Bank estimates that global remittances will reach $707 billion by 2016.2 Western Union, Money Gram, Ria Money Transfer, Dahabshill are just a few of the well-known companies that provide official remittance services for the world's migrants. Of course, banks and nonbank financial institutions are also used. In 2013, some of the top recipients for officially recorded remittances were India (an estimated $71 billion), China ($60 billion), the Philippines ($26 billion), Mexico ($22 billion), Nigeria ($21 billion), and Egypt ($20 billion). Pakistan, Bangladesh, Vietnam, and the Ukraine were other large beneficiaries of remittances. As a percentage of GDP, some of the top recipients were Tajikistan (48 percent), the Kyrgyz Republic (31 percent), Lesotho (25 percent), and Moldova (24 percent).3

These are estimates of what is officially remitted. Unofficially, nobody knows. However, the International Monetary Fund believes, “Unrecorded flows through informal channels are believed to be at least 50 percent larger than recorded flows.”4 So using the above World Bank and IMF estimates, unofficial remittances are enormous!

Sometimes touted as a new phenomenon and a symptom of the emerging borderless world, trade diasporas have existed since ancient times.5 Informal channels operate outside of the ironically labeled “traditional” channels. It's ironic because for most of the migrants involved, the alternatives to Western-style remittances such as via banks or Western Union are very traditional for them. Two of the largest alternative or informal systems are hawala and fei-chien (see Chapter 5)

Although diverse alternative remittance systems are found throughout the world, most share a few common characteristics. The first is that they all transfer money (or value) without physically moving it. Another is that they all offer the three Cs: they are certain, convenient, and cheap! And finally, historically and culturally, most alternative remittance systems use trade as the primary mechanism to settle accounts or balance the books between brokers.

Definition of Hawala

The definition of hawala was concisely expressed during the 1998 U.S. federal trial of Iranian drug trafficker and money launderer Jafar Pour Jelil Rayhani and his associates. During the trial, prosecutors termed hawala “money transfer without money movement.”7 That is, a broker on one side of the transaction accepts money from a client who wishes to send funds to someone else. The first broker then communicates with the second broker at the desired destination, who distributes the funds to the intended recipient (less small commissions at both ends). So the money (or value) is successfully transferred from Point A to Point B but the funds are not physically moved.

Hawala (also commonly known as hundi in Pakistan and Bangladesh) is an informal value transfer system based on the performance and honor of a huge network of money brokers, which are primarily located in the Middle East, North Africa, the Horn of Africa, and South Asia.

Hawala comes from the Arabic root h-w-l (![]() ), which has the basic meanings “change” and “transform.” The modern definition of hawala (

), which has the basic meanings “change” and “transform.” The modern definition of hawala (![]() ) is a bill of exchange or promissory note. It is also used in the expression hawala safar (

) is a bill of exchange or promissory note. It is also used in the expression hawala safar (![]() ) or travelers check. The Arabic root s-r-f (

) or travelers check. The Arabic root s-r-f (![]() ) has, among other meanings, “pay” and “disburse,” and the Arabic word for bank, masrif, (

) has, among other meanings, “pay” and “disburse,” and the Arabic word for bank, masrif, (![]() ), comes from this root. In Iran, s-r-f is also the basis for the Farsi words saraf (

), comes from this root. In Iran, s-r-f is also the basis for the Farsi words saraf (![]() ), which means a money changer/remitter, and sarafi (

), which means a money changer/remitter, and sarafi (![]() ), which is the name for the business. Afghan hawaladars sometimes refer to themselves as sarafi, or saraf in the singular.8

), which is the name for the business. Afghan hawaladars sometimes refer to themselves as sarafi, or saraf in the singular.8

The primary component of hawala that distinguishes it from most other formal financial systems is trust. This often revolves around the extensive use of family, clan, tribe, or regional affiliations. According to R. T. Naylor, an academic who has studied black markets, “Typically, entrepreneurial members of a trade diaspora make no distinction between social and economic life. Their business firms are extensions of kinship structure, with leadership that reflects the extended family hierarchy, which can extend across continents.”9 These are the attributes that also make it very difficult for Western law enforcement and intelligence services to penetrate the underground financial networks.

For example, law enforcement agencies in the United States typically do not have many Pashtu speakers, Farsi speakers, Gujarat speakers, and so on. And even if law enforcement recruited an agent to approach an underground hawala network, the very first question might be, “Who is your uncle in the village back in the old country?”

The opaque nature of hawala also explains why it is so attractive to criminal and terrorist organizations. Unlike Western banking, hawala makes minimal use of negotiable monetary instruments; instead, transfers of money are based on trust and communications between networks of brokers.

The Hawala Transaction

To illustrate how the hawala remittance process works, we will use a typical example. Ali is an Afghan national and a construction worker in New York City. During the long Taliban occupation of his homeland, he emigrated to the United States. He now earns money that helps support his family. He sends a portion of his salary back to his elderly father, Jafar, who lives in a village outside of Kandahar in southern Afghanistan. To make his monthly transfer—usually about $200—Ali uses hawala. This is very common in Afghanistan. About 30 percent of its population is externally and internally displaced, and remittances from outside of Afghanistan are received by about 15 percent of the rural population.11

If Ali went to a bank in New York City to send the money home to his father, he would have to open an account. He doesn't want to do that for a number of reasons. First, Ali grew up in an area of the world where banks are not common. He is not used to them and doesn't trust them. Next, Ali has little faith in governments and wants to avoid possible scrutiny. Many immigrants believe the government is monitoring their immigration status and/or will make them pay taxes. He also doesn't want the U.S. government to screen his money transfers to Afghanistan. In addition, although Ali has lived in New York for a few years, he is still a bit intimidated. His English is marginal. He is only semiliterate (approximately 80 percent of Afghanis cannot read or write) and cannot fill out the necessary forms. Moreover, banks charge their customers assorted transfer fees and offer unfavorable exchange rates. If Ali only earns a little money and is sending $200, bank transfer fees of 15 percent or more are quite substantial! And delivery of a bank transfer to Jafar would pose additional problems. The number of licensed banks in Afghanistan is still quite small. They are used by only about 5 percent of the population. Particularly in a poorly secured area such as Kandahar, Jafar does not want to leave his village home and travel a far distance to a bank.

In light of these problems and concerns, Ali uses a hawaladar in New York City who is a member of his extended clan and family. He feels comfortable dealing with him. The hawaladar also owns and operates a New York City–based “import–export” company. The hawaladar completes the transaction for a lower commission than banks or money services businesses charge. In addition, he obtains a much better exchange rate (the amount of afghanis—the local currency—for dollars). Delivery direct to Jafar's home in the Kandahar area village is also included in the price. In fact, in certain areas of the world, hawala is advertised as “door-to-door” money remitting.

In the New York portion of the hawala transaction, Ali hands over the $200 that he wants to transfer, from which the hawaladar takes his small commission. Ali is not given a receipt because the entire relationship is based on trust. This is a different kind of know your customer (KYC) procedure! For purposes of illustration, particularly if this is a first-time transfer, Ali may be given a numerical or other code, which he can then forward to Jafar. The code is used to authenticate the transaction. But the nature of hawala networks means that codes are not always necessary. As opposed to the often-lengthy formal operating requirements of bank-to-bank transfers, this informal transaction can be completed in the time it takes for the New York hawaladar to make a few telephone calls or send a fax or e-mail to the corresponding hawaladar in his network who handles Kandahar.

It is important to note that although some transactions are arranged directly, many are cleared or pass through regional hawala hubs such as Dubai, Mumbai, Karachi, and Kabul. So generally speaking, money can be delivered directly to Jafar's home within 24 hours and the transaction will not be scrutinized by either U.S. or Afghan authorities. The above scenario with Ali in New York City could just as easily take place in Minneapolis with its large Somali community, northern Virginia with its large Indian community, or Detroit with its large Arab community.

Similarly, hawala transfers are very common in London, Frankfurt, Dubai, Damascus, Baghdad, Tehran, Karachi, Zanzibar, Durban, the Colon Free Trade Zone, the Tri-Border region of South America, and many other locations around the world. For example, according to the U.S. State Department 2015 INCSR report, in the West African country of Gabon, “There is a large expatriate community engaged in the oil and gas sector, the timber industry, construction, and general trade. Money and value transfer services, such as hawala, and trade-based commodity transfers are often used by these expatriates, particularly the large Lebanese community, to avoid strict controls on the repatriation of corporate profits.”14 The important point is that in all locations, the hawala transfers occur without any physical movement of money (though hawaladars eventually have to settle with each other via methods described in this chapter).

The hawaladars conducting the transactions can offer better prices because they do not have to adhere to official exchange rates, and because they often have representatives in isolated or remote areas where banks do not operate. And for individuals who wish to conduct illicit business, hawala protects their confidentiality. Hawaladars maintain very few records, offering customers near anonymity. They only keep simple accounting records, and even these are often discarded after they settle-up with one another. This means the paper trail is limited or nonexistent, making transactions very difficult to track. Even when records are kept, they are often in a foreign language or code, making them very challenging for Western authorities to decipher.15

How Do Hawaladars Make a Profit?

Hawaladars have many advantages over formal money remitters. They generally do not have to maintain a large bricks-and-mortar storefront. Sometimes the brokers will run the money operation out of their homes; more often, they offer hawala in tandem with other businesses such as import–export companies, clothing stores, money exchange companies, gold and jewelry shops, carpet stores, cell phone/calling card shops, or even from their taxi or tea shop. The money they make from hawala fees reduces their overall operating costs and is easily integrated into normal business activities.

As indicated, many hawaladars also operate as currency exchangers, charging small commissions for the service and, in some cases, profiting from currency speculation or black market currency dealing.16 For example, restrictions enacted by many governments in South Asia often limit the amount of currency that can be taken out of the country. To get around the restrictions, hawaladars are able to provide “hard currencies” such as dollars or euros in exchange for local currencies such as rupees, dinars, or afghanis. In addition to low overhead, currency speculation is one of the principal reasons why hawaladars can beat the official exchange rates that banks offer. And in some areas, hawaladars also offer short-term lending, trade guarantees, and the safe keeping of funds.17

Figure 4.1 represents a prototypical hawala transaction.

- A person in Country A (sender) wants to send money to a person in Country B (recipient). The sender contacts a hawaladar and provides instructions for delivery of the equivalent amount to the recipient. A small percentage of the amount transferred is the hawaladar's profit.

- The hawaladar in Country A contacts the counterpart hawaladar in Country B via telephone, e-mail, or fax and communicates the instructions.

- The hawaladar in Country B contacts the recipient and arranges for delivery of the equivalent amount in local currency (sometimes requiring verification of a remittance code that the sender previously gave to the recipient). The hawaladar in Country B charges a small transaction fee.

- Per Figure 4.1, funds and value move in both directions between hawaladars in Country A and B. Over time, accounts may have to be balanced. Hawaladars use a variety of methods to settle the books. Historically and culturally, trade is the primary vehicle used to provide countervaluation between hawaladars.

Figure 4.1 Prototypical hawala transaction

Countervaluation and Trade

Hawaladars eventually have to settle their accounts with each other. Frequently, the close relationships between the brokers help facilitate the settlement. Remember, the key ingredient in hawala is trust. So kinship, family, and clannish ties often enable the settlement process. For example, in Afghanistan, intermarriages between the families of hawaladars are common because they help cement confidence between the parties. Brothers, cousins, or other relations often operate in the same hawala networks. They are not going to rip each other off! Lebanese family members that operate in the same hawala networks can be found in Beirut, Dubai, the Colon Free Trade Zone, and various locations in Africa. Yet even though they may be related by family or have tribal ties, they are still in business to make money. Money transfers between hawaladars are not settled on a one-to-one basis but are generally bundled over a period of time after a series of transactions. Payments go in both directions. For example, remittances may flow into South Asia from the United States and Europe, but money and various goods flow back as well. A variety of methods are used to make payments and settle the accounts.

Certainly, most major hawala networks have access to financial institutions, either directly or indirectly. A majority of international hawaladars have at least one or more accounts with formal financial institutions.18 Bilateral wire transfers between brokers to settle accounts are sometimes used. If a direct wire transfer is made between international brokers, hawaladar A would have to wire money directly to hawaladar B's account to clear a debt. This could be problematic because the banks' foreign exchange rate procedures would be triggered. So in this case, hawaladar A might choose to deposit the funds into B's foreign account.

Direct cash payments are also used to settle debts. This is particularly true in areas of the world that have cash-based economies. Sometimes we forget that hawala networks also operate domestically between states and provinces. For example, in Afghanistan, hawala networks are found in each of the 34 provinces. Periodically, the brokers settle accounts and generally use cash. Hawala couriers have been identified transporting money within Afghanistan and across the border into Pakistan. Cash couriers representing hawala networks also frequently travel from Karachi to Dubai to settle accounts. Moreover, gold is sometimes also used as a medium of settling accounts (see Chapter 6).

Although open source reporting is very sparse, there is reason to believe that some underground remittance networks are using cyber-currencies including bitcoins.19 This development could potentially have a great impact on the hawala settlement process. It would also further obfuscate the money trail for authorities. Similarly, mobile payments or M-payments—particularly via the use of cell phones—are an increasingly popular vehicle for the remittance of wages, transfer of money, purchase of goods and services, and the payment of bills. The ubiquitous cell phone now acts as a virtual wallet and has brought twenty-first-century financial services directly to the developing world's large unbanked population. Unfortunately, M-payments can also be used to structure or place illicit proceeds via the purchase of M-payment credits. This is sometimes called digital smurfing. And it is believed M-payments could be used in the settling of accounts between underground money remitters including hawaladars.20 There are also reports that informal banking schemes including M-payments have been used to help fund the terrorist group the Islamic State of Iraq and al Sham (ISIS).21

As we have seen, from the earliest times—before modern banking and contemporary monetary instruments—trade-based value transfer was used between hawala brokers to settle accounts and balance their books. And the use of trade remains widespread. Settling accounts through import–export clearing is somewhat similar to bilateral clearing using bank transfers, but it uses the import–export of trade goods. That is why many import–export concerns are associated directly or indirectly with hawaladars. If a debt needs to be settled, hawaladar A could simply send goods to hawaladar B such as gold, electronics, or myriad other trade items. Or at the end of a reporting period, if an outstanding balance exists between, for example, hawaladar A in Somalia and hawaladar B in Dubai, B can use a Japanese bank account to purchase cars for export to Somalia. Once the cars arrive, they would be transferred to A to settle the debt and/or sell them for profit. The transaction would clear the debt between the two hawaladars.22

Chapter 1's discussion of basic TBML techniques such as invoice fraud and manipulation is also in the hawaldars' playbook. As the reader recalls, to move money out, a hawaladar or his agent will import goods at overvalued prices or export goods at undervalued prices. To move money in, a hawaladar or his agent will import goods at undervalued prices or export goods at overvalued prices. This type of procedure is called countervaluation. Most other worldwide alternative remittance systems or informal value transfer networks are similarly based on trade. That is why a close examination of trade could be the back door to penetrating hidden hawala networks and is an additional reason why TBML should be the next frontier in AML/CFT enforcement. Trade transparency as a countermeasure will be discussed in Chapter 9.

An Abused Financial System

I want to emphasize that the overwhelming majority of people that use hawala and similar systems are not criminals or terrorists—they are simply trying to send or remit legitimately earned money. These transactions are sometimes called “white” hawala. Similar to Ali in the example above, a migrant worker chooses to use an alternative remittance system for both personal and practical reasons. Most governments do not have any desire to interfere with hard-working migrants who simply wish to send a portion of their wages back to their home country to help support their loved ones. Unfortunately, despite hawala's legitimate role as an alternative remittance system, the system is abused by criminals and terrorists who wish to transfer money and value securely, cheaply, and without transparency. Similar to the BMPE described in Chapter 3 and the Chinese flying money system described in Chapter 5, hawala as the informal value transfer system is abused. Although criminal transactions—often called “black” hawala—constitute only a very small percentage of total hawala transfers, they still add up to an enormous amount of money.

Even the mostly “white” nature of hawala poses a challenge. Just like money transfers via banks, money services businesses, or even sending value through trade, it is necessary to sift through the statistical noise of a lot of hawala transactions to find the occasional suspect or black hawala transfer. One prominent hawaladar and gold trader in Dubai I once spoke with said that in his experience, it would be necessary to examine 1 million to 1.5 million white hawala transactions to find one black transfer. Although this is undoubtedly a self-serving statement, and experience has shown in areas of Afghanistan and other problematic regions that there are hawaladars who specialize in illicit transfers, it highlights some of the obstacles to successfully monitor hawala networks and to employ effective countermeasures. As the Dubai source put it, governments can make all of the laws they want in an effort to regulate hawala, but the people will simply go around them and continue to use alternative banking, “until there is no longer a need for the service.”24

How to Recognize Hawala

Both black and white hawala transactions are generally off the authorities' radar screens. In this respect, hawala represents one of the major “cracks inside the Western financial system” that Osama bin Laden once emphasized.25 As indicated, I believe a concerted international effort to promote trade transparency could be the back door into hawala and many sister underground financial systems. But even without trade transparency, there are some ways to better identify the system and its abuses.

In general, some hawala networks are quite open while others are opaque. Many hawaladars operate in plain view in cities and town throughout the Middle East and Africa, particularly within souks (markets). Sometimes a particular city street or area of a souk will have a concentration of hawaladars and other types of financial businesses. Typically, they will advertise themselves as “money remitters,” “money changers,” “foreign exchange dealers,” and “door-to-door” money delivery services. The word hawala itself is rarely used. In some areas (including the United States), the shop titles are displayed in both English and the native language. Certain businesses are more likely than others to be involved with hawala. While the following is not an exhaustive list, the following types of establishments have been known to offer hawala or similar services:

- Import–export or trading companies

- Travel and related services

- Jewelry dealers (particularly buyers and sellers of gold)

- Foreign exchange companies

- Sellers of rugs and carpets

- Used car sales

- Telephone/calling card sales

- Ethnic restaurants

Hawaladars sometimes operate out of their homes, attracting customers by word of mouth or relatively inexpensive forms of advertising such as flyers or signs in shop windows. Again, the word hawala will not be used in most cases. For example, a hawala advertisement in New York City might look similar to that shown in Figure 4.2.

Figure 4.2 Sample hawala advertisement26

From John Cassara and Avi Jorisch, On the Trail of Terror Finance: What Law Enforcement and Intelligence Officers Need to Know (Red Cell IG, 2010).

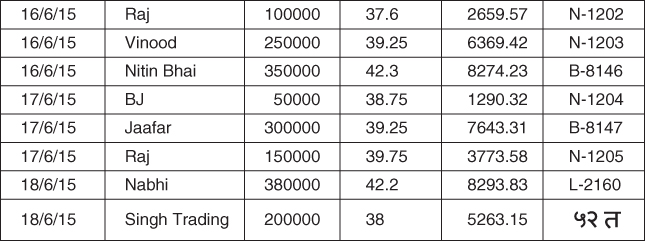

“Following the money” in hawala investigations is very difficult. By their very nature, the transactions are underground and there is generally very little financial intelligence or other paper trail to follow. In most areas, customer identification is not required and formal recordkeeping is rare. Yet, most hawaladars maintain ledgers to record transactions, sometimes even in computerized spreadsheet form. Hawala bookkeeping emphasizes keeping track of how much money is owed and to whom. The sample ledger in Figure 4.3 is representative of the kind of record that might be kept. (Note that these ledgers are usually handwritten, and it is not uncommon for the native language to be used.)27

Figure 4.3 Sample hawala ledger

From John Cassara and Avi Jorisch, On the Trail of Terror Finance: What Law Enforcement and Intelligence Officers Need to Know (Red Cell IG, 2010).

The first column indicates the date of the transaction. The second column shows the name of the hawala broker to whom the debt is owned; partial names (e.g., “Raj”) or codes (e.g., “BJ”) are often used. In this example, the names are Indian. The third column is the amount of the debt. This ledger reflects a tendency to do business in multiples of 100,000, so it would not be uncommon to see notations like “1.5” for 150,000. The fourth column indicates the dollar/rupee exchange rate in effect for the transaction. The fifth column is the value of the transaction in dollars. The sixth column reflects the manner in which the payment was made. Notations such as “N-1203”) usually represent a bank and a check number. (N could be “National Bank,” B could be “Basic Bank,” and L could be “Local Bank.”) In many locations in the Middle East and South Asia, however, checks are not used, and payments/deposits are in cash. In such cases, a remittance code may be designated. In the sample ledger, the notation ![]() in the Singh Trading row is “52 T” in Hindi. This represents 52 tolas of gold, possibly paid to a local goldsmith or jeweler instead of being remitted via a bank (see Chapter 6 for more on gold transactions).

in the Singh Trading row is “52 T” in Hindi. This represents 52 tolas of gold, possibly paid to a local goldsmith or jeweler instead of being remitted via a bank (see Chapter 6 for more on gold transactions).

Countermeasures

After September 11, a buzz developed in the worldwide media about terrorist finance. There were published stories about al Qaeda's alleged exploitation of gold, diamonds, tanzanite, and even the honey trade. Articles were written about the abuse of charities and donations from wealthy individuals in the Middle East to finance terror. But perhaps the biggest “discovery” for both the media and government agencies and departments was hawala. Talking heads and so-called experts gave interviews and were asked to testify on Capitol Hill about the threat of hawala and other alternative remittance systems that might be exploited by our adversaries. Congress wanted a solution, or at least the appearance of a solution, for an underground system that doesn't have a solution.28

Hawala—and similar alternative remittance systems—are here to stay. They are not going away because they fill a need. Moreover, hawala is intertwined with complex issues such as macro and micro economics, currency exchange controls, the devaluation of currencies, tax avoidance, capital flight, illiteracy, underground trading networks, and the promotion of banking services to non-banked populations. New laws, rules, and regulations in the United States and other jurisdictions are not going to solve the problem. Certainly, the last 10 years have proven that the registration and licensing requirements of hawaladars are mostly cosmetic.29

In short, there is no silver bullet to prevent the misuse of hawala. Yet we should not stop trying to develop and implement countermeasures or ways to identify suspect hawala transactions. We know trade is still the most widespread method of settling accounts between hawaladars and other underground financial brokers. As I have urged elsewhere, a systematic examination of suspect trade anomalies could provide insights into hawala networks.

Case Examples: Hawala

The following are a few examples of “black” hawala. They are representative of cases that use hawala both to launder criminal proceeds and also finance terror.

Case 1: Manhattan Foreign Exchange

On March 20, 2003, law enforcement agents in New York arrested four individuals in connection with a Pakistani unlicensed money services business called Manhattan Foreign Exchange. Run from the basement of a Kashmiri restaurant in midtown Manhattan,30 the business was one of New York's largest hundi remitters to Pakistan, transferring more than $33 million to the country during a three-year period, mostly drug proceeds.31 The criminal organization also sold fake U.S., Pakistani, Canadian, and British passports and travel documents.32

Shaheen Khalid Butt, the Kashmiri owner, was charged with money laundering, currency reporting violations, conspiracy, and immigration fraud charges.33 Over the course of the investigation, law enforcement bugged the basement of the restaurant and videotaped couriers dropping off bags of cash.

Case 2: Shidaal Express

In November 2013, a federal judge in San Diego sentenced three Somali immigrants for providing financial support to al-Shabaab—a designated terrorist organization. Evidence presented during the trial showed the defendants conspired to transfer funds to Somalia through a hawala operation known as the Shidaal Express. Among those involved in the conspiracy were Basaaly Saeed Moalin, a cabdriver, Mohamed Mohamed Mohamud, the imam at a popular mosque frequented by the city's immigrant Somali community, and Issa Doreh, who worked in the hawala operation that was the conduit for moving the illicit funds. Moalin had direct ties with al-Shabaab and one of its most prominent leaders—Aden Hashi Ayrow. At the trial, the jury listened to dozens of the defendants' intercepted telephone conversations, including many between Moalin and Ayrow. In those calls, Ayrow begged Moalin to send money to al-Shabaab, telling Moalin that it was “time to finance the jihad.”34

Case 3: Health-Care Fraudsters Send Funds to Iran

In March 2013, Hossein and Najmeh Lahiji, a naturalized U.S. citizen and his wife, were indicted for medical billing fraud in Texas, and for sending the illicit proceeds to Iran via hawala. The Lahijis transferred the illicit funds through Espadana Exchange, an unlicensed money remitting business. During the investigation, evidence was obtained that allegedly showed the co-conspirators defrauding multiple health-care benefit programs by submitting false and fraudulent claims, including instances where Dr. Lahiji submitted claims for urology services allegedly performed when in fact he was traveling outside the United States.35

Case 4: Somali Remittances

In Somalia, there is an absence of regulated commercial banks. As a result, informal remittance companies are the primary conduits for moving funds into and out of Somalia. Trade goods are often used to settle accounts between hawaladars. In one case, a Somali trader buys commodities from Dubai for resale in Somalia. To finance the trade, the Somali trader contacts a local remittance company in Mogadishu. The trader gives cash to the local remittance agent. (Most transactions are dollar-based, but other currencies are used as well.) A commission is charged for the exchange. The trader asks that the funds be transferred to his foreign bank account located in Dubai.

The local agent of the remittance company contacts a hawaladar also located in Dubai and asks that the funds be transferred to the Dubai-based bank account identified by the Somali trader. The Dubai bank issues a letter of credit so that goods can be purchased. The desired goods are purchased in Dubai and the vendors have no idea—nor do they care—that the origin of the funds is actually the result of a hawala exchange. The trade goods are then shipped to Somalia and sold by the trader. A percentage of the profit is kept and the balance is used to pay suppliers, and the cycle is repeated.36

Case 5: Financial Intelligence Instrumental in Hawala Investigation

In 2002, the FBI opened an investigation into the activities of a hawaladar in the western United States. A tip from a citizen complaint prompted a query of the BSA database. The query yielded 30 SARs and 13 CTRs, which were instrumental in identifying numerous bank accounts used in the hawala operation. Over a five-year period, the subjects, all Iraqi immigrants, wired in excess of $4 million from a U.S. bank to accounts in Amman, Jordan. From there, most of the money was illegally smuggled into Iraq. Additional funds were sent to Syria, Saudi Arabia, Iran, UAE, Chile, Ukraine, and Denmark.37

Cases 6 and 7: Examples of Hawala and Terror

According to transcripts from the trial of Mohammed al-Owahali, an al-Qaeda member serving a life sentence for his role in the 1998 U.S. embassy bombing in Nairobi, funding for the attack was received through a hawala office in the city's notorious Eastleigh district, a predominantly Somali neighborhood.38 And according to the indictment of Faisal Shahzad, the Pakistani American who attempted to detonate a bomb-laden SUV in New York's Times Square in May 2010, hawala transfers were used to finance that plot as well. Shahzad reportedly received approximately $12,000 from the Pakistani Taliban to carry out the attack.39

Cheat Sheet

- The magnitude of unofficial remittances is enormous, easily surpassing multiple hundreds of billions of dollars a year.

- Hawala is one of many worldwide alternative remittance systems. It is commonly found in South Asia, parts of Africa, the Americas, and the Middle East.

- Hawala can be defined as “money transfer without money movement.”

- The overwhelming majority of hawala transactions are benign and involve the remittance of wages.

- Hawala is based on tust. It works primarily because of family, clan, or tribal associations.

- Transfers of money and value take place based on communications between members of a network of hawala brokers, called hawaladars.

- Attractive elements of hawala are that it is certain, convenient, and cheap. Clients also feel comfortable working with a financial system they trust and understand.

- Accounts between hawaladars are periodically settled through banks, cash couriers, and trade. New settlement techniques such as cyber- and mobile payments are on the horizon.

- Hawala brokers frequently operate other businesses. Some of the most common include currency exchange houses, import–export shops, cell phone/calling card shops, gold jewelers, and various kinds of business brokers.

- Hawala is widespread even in jurisdictions where it is technically illegal.

- Hawaladars generally keep temporary books or an informal ledger to track their transactions.

- Hawala countermeasures have proven ineffective in part because the service is interwined with regional issues such as illiteracy, currency devaluations, nonconvertibility of currency, excessive taxation, corruption, lack of inexpensive financial services, and trade and value transfer.