CHAPTER 4

EXECUTING THE VIRTUAL PROJECT

The project manager's planning work is just that, planning. There is a reason you see coaches and managers on the sidelines during games; they are needed as much then as they are needed during practice. If practice was the only important aspect of a coach's role, there would be no need for her or him during the game, where all that practice is executed. The same can be said for virtual project managers as projects move into execution.

If planning work was done well, an integrated project plan will be created that represents the collective work that needs to be accomplished by the team during project execution. If best practices for virtual projects were used, there was likely one or more face-to-face meetings to solidify the project charter and team charter, cement project member roles and expectations based on the project's business case, demystify any assumptions or rumors about any team member and cultural beliefs, and enjoy some social time to get to know one another and establish team chemistry. Hopefully, this did occur; even if it did, though, it does not mean that the synergy will be maintained once the team and the work are redistributed geographically, organizationally, and culturally. A one-time face-to-face meeting or event does not make a team perform at a high level. The most important aspect of any such event is not the event itself but what happens afterward. (See the box titled “Actions Speak Louder than Words.”)

The executing stage is arguably the most anticipated stage of a project's life cycle. It is when an intangible concept moves forward to become a usable, tangible asset for the business. It is also the part of the project in which the quality of the integrated project plan and the ability of project managers will be put to the test.

The job of managing a virtual project during the executing phase can be challenging due to a couple of natural factors. First, the size of the project team and the number of project interdependencies to track and manage grow rapidly from planning to executing. Staff size, budgeted dollars, and the number of project interdependencies are at their highest levels during this stage of the project. Project managers must closely manage these factors to ensure that the project stays in alignment with the business objectives and that the triple constraints are balanced.

Table 4.1 Base Assumptions for Project “Amherst”

| Assumption | Status |

| Resources will be available at project kick-off. | Open |

| Technical staff is fully trained. | Confirmed |

| Business requirements are completely documented. | Open |

| Full budget is available at project initiation. | Confirmed |

| Equipment order lead times are known and can be met. | Open |

| System components will be able to be integrated with minimal rework (three weeks maximum). | Open |

| No outsourced work will be required. | Confirmed |

| Strategic customers will participate in beta testing of the product. | Open |

The second factor that complicates the management of virtual projects is, of course, the geographic distribution of the work caused by the distribution of the team. Monitoring, adjusting, integrating, and changing the work of the project team is complicated by the distance and time factors associated with virtual projects. Because of these complex factors, there are more nuances for virtual project managers to address. This chapter details those nuances, best practices, and solutions to enable project managers to overcome the challenge of virtual project execution.

Managing Assumptions

Few, if any, projects begin with absolute certainty of how their execution and outcome will play out. In reality, more is unknown than known during the planning stage of a project. This is due to the fact that project planning is about trying to predict the future, and even the most gifted project managers do not possess a crystal ball to foresee future events. As projects are planned and executed, some facts are known while the remainder must be estimated based on a set of assumptions of how the future will unfold. An assumption is a likely condition, circumstance, or event that is presumed known and true.

Assumptions and constraints form the basis of the project plan and must be closely monitored during project execution to ensure that the plan remains viable. If not, changes will need to be made. For example, a constraint for a particular project may be that $200,000 has been allocated to complete the project (the project budget). A base assumption of the project may be that the $200,000 budget is sufficient to complete the project. If this assumption is proven untrue, changes will need to take place during project execution to realign reality and the constraint.

Project Assumptions Identification

The first and most crucial step in managing assumptions is identifying the base assumptions on which the project plan is established. If assumptions are not identified and made visible, they cannot be managed. Identification of assumptions is important on all projects, but even more so for virtual projects because the validity of the assumptions has to be assessed wherever the work is being performed. Managing the base assumptions is therefore a shared and distributed task on virtual projects. For this reason, it is necessary to clearly document the base assumptions for the project, as illustrated in Table 4.1.

Assumptions Validation

The best-case scenario is one in which all assumptions are validated as truisms during project planning so the team begins execution activities with a full set of knowns. This is an extremely rare scenario, unfortunately. In reality, the validation of assumptions becomes a primary activity during project execution that feeds both the risk management and change management processes. Because of its importance, assumption validation has to be centralized and performed by virtual project managers (with critical input from project team members). As a best practice, the assumption list should be reviewed during each team meeting to maintain focus and effort on validating the base assumptions of the project.

Assumptions Control

Initial assumptions are rarely static. As a project evolves, more will be learned about the future, and assumptions will be proven true or untrue in the process. When an assumption is proven to be untrue, action must be taken. Likely, a project risk will be associated with the false assumption that will require mitigation or elimination. The risk mitigation or elimination action will in turn likely result in a change to the project baseline. Project assumptions, risks, and changes need to be closely managed as they, many times, are closely related and dependent on one another.

Documenting and validating the base assumptions on which the project plan is established enables a more proactive approach to managing the execution of a virtual project. Risks and changes can be identified and responded to in a timelier, and many times in a less disruptive manner if assumptions are tested early and regularly as part of the project execution process.

Hyper-vigilant Governance

“Monitoring progress on a virtual project is like status on steroids.” That is how Giovanni Mazzolli sees governance for a virtual project. Mazzolli, a virtual project manager in the automotive industry, is not alone in his view of virtual project governance. When we began our research for this book, we established a panel of experienced virtual project managers. The goal in doing so was to get a wide variety of practice-based perspectives pertaining to managing virtual projects and leading virtual teams. We began with one question: “What are the three main differences between traditional projects and virtual projects?” We received many great answers, most of which are included in this book. However, the answer we received the most often supports Mazzolli's assertion that hypervigilant project governance is a primary discriminator between traditional and virtual projects. Here is a sample set of other responses we received:

- “I have experience with both co-located and virtual teams and I find the main difference is during execution and when performing monitoring and control.”

- “When you track progress during execution, I find it very different when it has to be done remotely. When done remotely, the process of reporting is more structured. We set the days we meet and the days I get an email status report.”

- “When working with a local team, monitoring is less formal. I tour the office every morning and do a ‘what's new’ survey of team progress. When monitoring remotely, it is more important to use defined reporting cycles and common dashboards.”

The distribution of work in the virtual environment makes project monitoring and control so challenging and so important. Studies regarding virtual team governance reveal that stage gate–based systems are reasonably standard in project governance for reviewing and approving established project milestones and critical decision points. Further, metrics and dashboards are used for measuring and tracking progress and related success factors and are used as decision support tools. Such tools are used to keep execution aligned with business objectives and to illustrate what is working well and what needs additional effort relative to the project success factors. The governance process and tools will indicate when course correction becomes necessary.1

A solid governance system also requires that periodic reporting and assessing takes place consistently and across the organization by each project manager and project team. Additionally, responsibility and authority is assigned to managers and project managers possessing governance responsibilities to ensure that actions and decision making are occurring as intended. The consistent application of the governance system is necessary to provide the highest probability of achieving the intended project objectives. This point cannot be overemphasized as it pertains specifically to virtual projects that face challenges associated with the virtual team environment.2

The Project Management Institute defines project governance as the alignment of project objectives with the strategy of the larger organization by the project sponsor and the project team.3 A project's governance is defined by and is required to fit within the larger context of the organization sponsoring it, but is separate from organizational governance. Project governance manifests itself as an oversight activity that most organizations consider a subset of the broader organizational governance activities defined by the project life cycle. The project governance framework normally includes such things as structure, processes, decision making models, and tools for monitoring and controlling the project. A robust project governance system has three primary functions:

- Establish and maintain the project goals, objectives, and linkage to the organization's strategic goals.

- Ensure the right structures are in place to achieve the project goals and objectives.

- Monitor and direct the project to ensure that stated project objectives and business benefits are realized.

Most organizations have a strong link between internal project governance activities normally managed and led by project managers and the broader organizational governance system established by the enterprise. Projects are initiated to achieve business goals, and as a result, project success is judged on the basis of the achievement of those goals.

Start with Defining Project Success

The first principle of good project governance involves understanding and communicating how well project performance is progressing toward achievement of project objectives. Many times project managers become over focused on progress against their cost and schedule baselines and forget that the real intent of a project is to achieve the business objectives driving the need for the project.

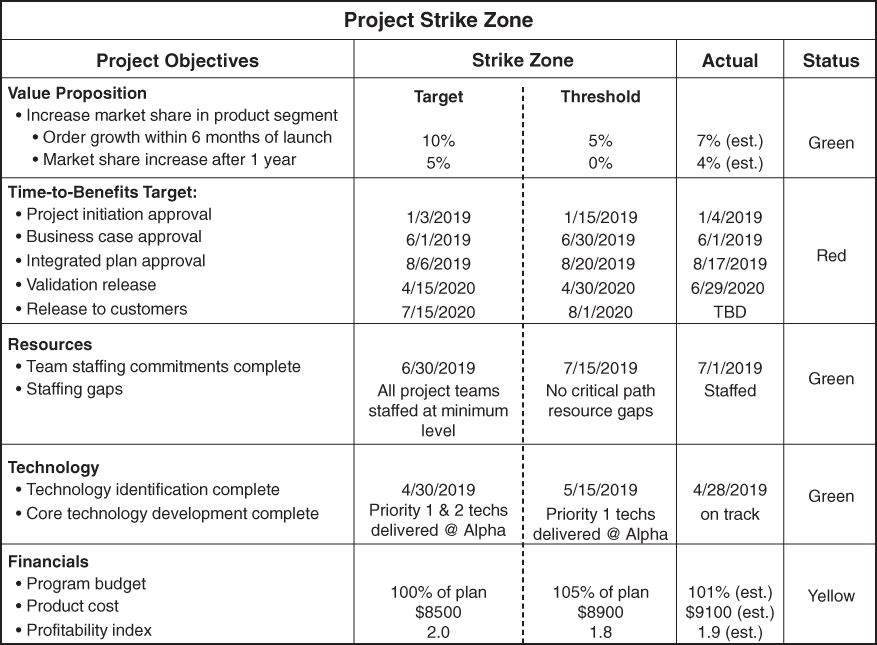

The project strike zone is an excellent tool for evaluating and communicating progress toward achievement of the project objectives. It is used to identify the critical objectives for a project, to help project managers and their stakeholders track progress toward achievement of the key business results anticipated, and to set the boundaries within which project managers and teams can operate without direct top management involvement.

As shown in Figure 4.1, elements of the project strike zone include the project objectives, target, and threshold values, an “actual” field that provides indication of where a project is operating with respect to the target and threshold limits, and a high-level status indicator.4

Figure 4.1 Example Project Strike Zone

Creating an effective project strike zone is a critical activity for ensuring that project managers, project teams, top management, and other stakeholders all understand and agree on the objectives of the project. It is also critical for establishing the success measures to monitor during project execution in order to gauge project progress.

Defining a meaningful project strike zone requires quality information from a number of sources. The initial set of objectives is derived directly from the approved project business case. (See Chapter 2.) To establish and later negotiate the control limits for each objective with project managers, project sponsors also need to know the project team's capabilities and experience and past track record and to balance thresholds against the new project's complexities and risks accordingly. The four steps for creating and using a project strike zone are:

- Identify project objectives.

- Set the recommended target and threshold values.

- Negotiate the final target and threshold values.

- Use the project strike zone for virtual governance.

Identify Project Objectives

Identification of the project objectives begins during the initiation stage of a project. The objectives represent a subset of the metrics normally tracked by a project team. The project strike zone should include only the measures that represent the high-level project objectives (often the business objectives). The project objectives will be unique to every organization and are derived directly from strategic management and portfolio management processes.

The strike zone is most effective when the objectives identified are kept to a critical few (usually five to six), as this focuses the project and top management's attention on the highest priority contributors to project success. The factors deemed must-haves often include market, financial, and schedule targets and the value proposition of the project output.

Set the Recommended Target and Threshold Values

The target and threshold control limits shown in Figure 4.1 form the strike zone of success for each project objective. The target values for the objectives in the project strike zone are the objectives as specified in the project business case and baseline plan. The target values should be pulled directly from the project business case.

The threshold values represent the upper or lower limit of success, as specified by senior management for the project objectives.5 Some discussion and debate is normally required to understand how far off target an objective can range and still constitute success for the project. For example, the target project budget may be set to $500,000. But, if additional spending of 5% is allowable, then the budget threshold can be set at $525,000. This means that even though a project team misses the target budget of $500,000, it still is successful from a project budget perspective if it spends up to $525,000.

Negotiate the Final Target and Threshold Values

Once project managers establish the recommended target and threshold values for each project objective, they present the information to the senior executive sponsoring the project. Based on the project's complexity and risk level, and on the capability and track record of the project manager and team, the project sponsor may adjust the values accordingly. For example, on a project that is low complexity, low risk, and is being managed by an experienced project manager, the range between target and threshold values may be opened up to allow for a higher degree of decision making empowerment for the project manager. Conversely, on a project that is of higher complexity or risk or is being managed by an inexperienced project manager, the range between target and threshold values will be tightened up to limit the project manager's decision making empowerment.

Once the targets and boundaries are negotiated, the team should be empowered to move rapidly as long as members do not violate the strike zone threshold values.

Use the Project Strike Zone for Virtual Governance

The project strike zone adds value in many ways to project managers, the executive sponsor of a project, and the project governance body. Project managers utilize it to formalize the critical project objectives for the project, to negotiate and establish the team's empowerment boundaries with executive management, to communicate overall project progress and success, and to facilitate various trade-off decisions throughout the project life cycle.

Executive managers utilize the project strike zone to ensure a project supports the intended business objectives and to establish control limits to ensure that the project team's capabilities are in balance with the specific project's level of complexity. When used properly, the project strike zone provides top managers a forward-looking view of project alignment to business objectives. When problems are encountered, the tool's structure provides an early warning of trending problems, followed by a clear identification of “showstopper” conditions based on the level of achievement of project objectives. If a project is halted, senior executives can reset the project objective targets or thresholds, modify the scope of the project to bring it within the current targets, or, in the extreme case, cancel the project to prevent further investment of resources.

Executive managers and the project governance body set the boundary conditions (targets and thresholds) of the project strike zone between which project managers can operate, thereby empowering project managers to make decisions and manage the project without direct top management involvement. As long as the project progresses within the strike zone of each project objective, the project is considered on track, and project managers remain fully empowered to manage the project through its life cycle. However, if the project does not progress within the strike zone of each project objective, the project is not considered on track, and the top managers must intervene directly.

When the project strike zone is used appropriately, the project manager and team are empowered because boundaries for authority, responsibility, and accountability are established. Too often, project managers tell us that they have all the responsibility for driving project success but lack the authority. The project strike zone is the best tool we are familiar with to balance responsibility with the appropriate level of authority.

Monitor Distributed Work Closely

Project monitoring is a critical aspect of virtual project governance. Due to the distributed nature of work on a virtual project, project managers have to be hyper-vigilant about collecting team status and monitoring progress to plan. They must do so on a schedule specified by their respective senior management and project sponsor in an organized manner.

Many times monitoring cadence is dependent on where the project is in its life cycle, as Jerry Conners, an experienced virtual project manager, explains:

During the early and middle stages of project execution, I rely on our weekly team meeting to collect status from the distributed team members. This is my normal reporting cycle. During final integration and testing, we will go to daily stand-up meetings to make sure action and re-action is quick.

Monitoring is the delicate balance between not diving too deep, because virtual project managers will quickly realize that there is not the time to do so, and not diving deep enough to monitor project progress and team health. Best-practicing virtual project managers realize that as managers, they are part auditor and therefore need to take on a “just don't tell me, show me” attitude (see the box titled “Using Weekly One-on-Ones to Capture Dashboard Data and Build Rapport”).

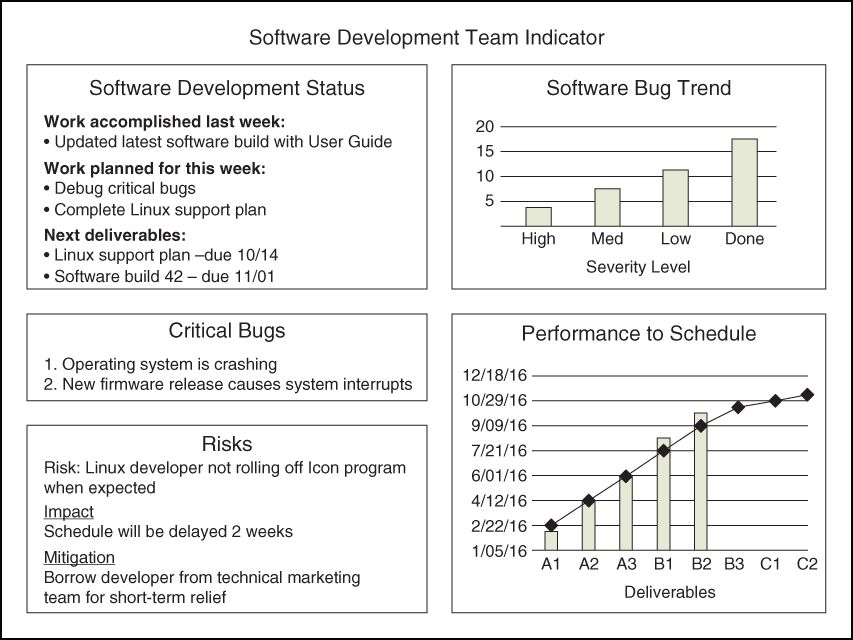

Figure 4.2 Example Team Indicator Report

Project managers need to see work completion to fully trust it is getting done. It is a trust but verify management style and is accomplished in two ways. The project managers intentionally design project schedules and integration points that are closely associated in time. In other words, best-practice virtual project managers never have decision points, milestones, or deliverables that are months into the future. All such key points on a schedule are no more than two to three weeks out, which means there are always touchpoints to verify actual progress.

To facilitate consistent intra-team progress reporting, virtual project managers can require team leaders to prepare and present a team indicator that reflects the work of their team of specialists. Keep in mind that, for some distributed team members, it may be a team of one specialist. Figure 4.2 shows an example project team indicator report that can be adapted for a team's special situation and information requirements.

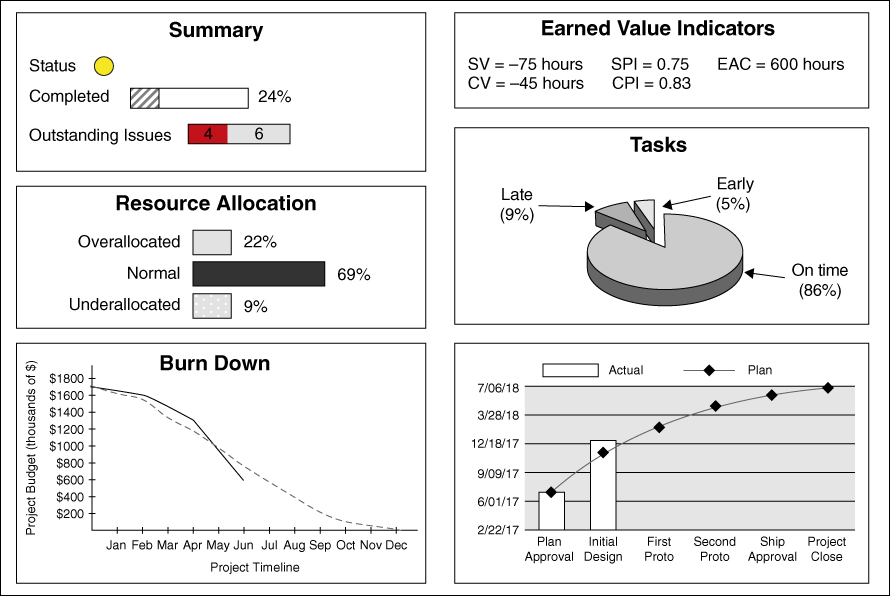

Figure 4.3 Example Project Dashboard

Project managers must work with the team to determine the best format and content to present in the team indicator. Content includes progress to planned work since the last reporting period, work planned during the next reporting period, critical issues and risks needing project manager attention, changes agreed to through the team's change management process, and performance to a team's performance metrics. By requiring team members to keep their indicators current, project managers will receive a comprehensive yet concise report on team status. As an effective communication tool, the team indicator facilitates the necessary transfer of status information between the distributed team member and the virtual project manager.

Consolidating Project Status Information

In today's frenzied pace of virtual projects, project managers need to understand how the project they are responsible for is performing, but they rarely have time to read through a number of detailed status reports from their functional teams. From this time-versus-information dilemma grew the concept of the project dashboard.6

Much as the dashboard of an automobile provides drivers with a quick snapshot of the current performance of the vehicle, the project dashboard provides project managers with an up-to-date view of the current status of the project. Unlike the project strike zone, which focuses on performance against the higher-level project objectives and business goals, the project dashboard focuses on the current state of the lower-level key performance indicators (KPIs).

The dashboard should be designed as an easy-to-read and concise (often a single page) representation of all KPIs as illustrated in Figure 4.3. The information presented on a dashboard will vary by design, but typical items include:

- Key decision dates (this week, next 3 weeks, following 2 months)

- Upcoming milestones (this week, next 3 weeks, following 2 months)

- Upcoming deliverables (this week, next 3 weeks, following 2 months)

- All key integration points

- Project quality

- Project cost

- Project risks (top 3)

- Key stakeholder engagement meetings/discussions

- Team resourcing metrics (current and forecasted allocation)

There are many types of project dashboards in use and available for reference when designing a customized dashboard that represents the information most relevant and critical to a project. We like the design of the dashboard shown in Figure 4.3 because of its graphical nature, the variety of project status measures it provides, and its conciseness.

Designing a Project Dashboard

The project dashboard is one of the most flexible and customizable tools in a project manager's toolbox. As stated earlier, it needs to be designed around the particular KPIs of a project. Since each project is unique, each project will have somewhat unique performance indicators and therefore likely will have a unique project dashboard design.

Design of the project dashboard begins with the identification of the KPIs for the project. The project objectives, identified and quantified in the project strike zone, define the end-state of the project in terms of what value the project brings to the sponsoring organization. The KPIs quantifiably measure how well the project is performing toward accomplishing the project objectives. These measures typically can be found in other tools, such as the project business case or project charter. (See Chapter 2.)

The project KPIs are part of a measurement hierarchy that must be understood. Business outcomes support an organization's strategic goals, project objectives support the business outcomes, and KPIs support the project objectives. If, for instance, a strategic goal for an enterprise is to be the leader in a particular market segment, a business outcome in support of that strategic goal would be first-to-market advantage with new products or offerings. A project objective would, in turn, have to quantitatively define the project completion date that ensures first-to-market position for the project outcome. Two important project KPIs would likely complete the measurement hierarchy: performance to schedule and resource allocation percentage. (If resources are not close to 100% allocated to plan, the schedule likely will suffer.)

The KPIs identified in the project dashboard should directly measure performance toward achieving the project objectives documented in the project strike zone. The KPIs represented in the project dashboard in Figure 4.3 include performance to schedule, performance to budget, performance to cost, and resource utilization. Since resources are geographically distributed on a virtual project, resource utilization should always be viewed as a must-have performance indicator for any virtual project.

The final step in designing the project dashboard involves locating the pertinent performance data and representing it on the dashboard. Whenever possible, graphical representations should be used, as they facilitate speedier analysis of the current performance on the part of recipients than text-based representations, and they are easier to communicate to project stakeholders.

Some project managers embed hyperlinks within the top-level performance graphics that link to detailed data about the KPI of interest. For instance, if additional detail is needed for the performance to schedule KPI, a link can be provided to a detailed Gantt chart, milestone analysis chart, or even the schedule section of the current detailed status report for the project.

Project managers can use project dashboards as both communication tools and decision support tools. By using project dashboards to synthesize lower-level performance data into higher-level information, project managers are armed with the information they need to communicate the current status of the project with respect to the KPIs. Additionally, many decisions have to be made during the course of a project, some large and some small, and project dashboards serve as bases of past and current information from which decisions can be driven. (See the box titled “Tips for Using Project Dashboards.”)

Project Reviews

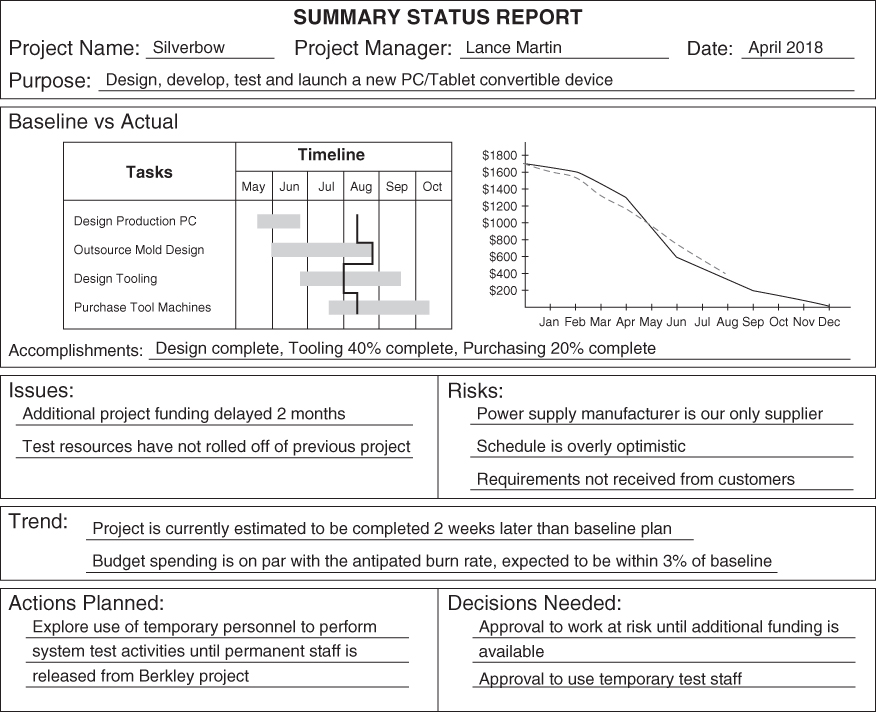

The project review is an organizational meeting in which project status is presented to and reviewed by senior managers, governance board personnel, and other key stakeholders. Given the virtual project team environment, most of these reviews are held by video conference across multiple company sites. Each project manager will present the status for the project he or she manages.

For consistency in reporting format and message, it is most effective to have a consistent project summary status report for use by all project managers. Much like the project dashboard, which is used to communicate intra-team status, the project summary status report is a one- or two-page summary brief that communicates overall project status to a broader set of stakeholders. (See Figure 4.4.)7 Much of the information contained in the status report is derived from the most recent team indicators and presented in summary format.

Figure 4.4 Example Project Summary Status Report

In addition to the summary status report, the project strike zone and project dashboard tools are normally used in the project review to communicate status toward achievement of the project business goals and KPIs, respectively. It is important to point out that the project review serves a dual purpose. First, it provides the data and information necessary to ensure that a project is progressing as anticipated, and second, it provides the necessary information to assist senior management and the governance body to make decisions with respect to business value and strategic direction. In the project review, the objective for project managers is to communicate both operational and strategic status of the project and to use the forum to gain management help if needed for specific issues or barriers outside of the project managers' control.

Managing Outsourced Project Work

Virtual project teams, just like traditional project teams, periodically face the need to outsource elements of work to other companies or subcontractors. Many times this need arises because the expertise or specialty skills required to complete the work do not reside entirely within the organization or company managing the project.

It is important to note that outsourcing a portion of a project to another company does not relieve project managers of the need to effectively manage the outsourced work to required specifications, delivery, and quality expectations and periodic progress reporting from the owner of the contracted portion of the project.

Leading and managing outsourcing is more challenging for a virtual project team than for a traditional team because of the additional oversight needed due to virtual distribution of the work. Some management and coordination elements for the virtual team leader to keep in mind are listed next.

- Ensure the right virtual project personnel are directly involved in the outsourced work to provide necessary guidance.

- Provide specific and detailed specifications and requirements to the outsourced agent. Most likely, this very specific information will be contained in a written contract.

- Require a project plan from the outsourced agent that specifies schedule, deliverables identified, and testing required before the release of the work. Virtual project managers will incorporate this useful information into the integrated project plan.

- Require periodic status reports and special meetings to address progress, issues, and risks as they arise, and consistently monitor progress of the outsourced work.

- Be ready and available to address the outsourced contractor's questions, concerns, issues, and requests for additional information in a timely manner.

Like all virtual team members, virtual project managers must be willing to invest face time with the outsource agent to build relationships, trust, and a physical presence that will carry forward in time.

Managing Change

Change happens often and quickly on any project. As soon as a project baseline is set, something is sure to change in the project environment that will test the need to adjust that baseline. The same is true on virtual projects, but the probability of unmanaged change creeping in is much higher on a virtual project due to the distribution of work geographically. Diligent and visible management of change is a must on a virtual project and constitutes a large portion of virtual project managers' effort during project execution. To lower the risk of unmanaged change, three practices are important:

- Gaining visibility to change that is occurring remotely and virtually.

- Establishing a robust change management process for the project.

- Efficiently communicating all changes that have been approved and declined to the virtual team and key stakeholders.

Gaining Visibility to Change

The biggest challenge to managing change on a virtual project is dealing with changes that can occur remotely before they happen. Proactive management of change can occur only if project managers establish a change management system for their virtual projects. A formal change management system establishes order to the job of collecting, analyzing, documenting, approving, and communicating project changes. Such a system also establishes the protocols, or rules, that define the expectations for how change will be managed once a project is in execution.8 Change management protocols normally include these points:

- All changes must be requested.

- Change requests must be made in writing.

- The benefits gained from a proposed change must be clearly articulated and documented.

- The approval process must be documented.

- A decision maker must be appointed.

- Approved changes must be incorporated into a revised project plan.

- Change decisions must be adequately communicated.

A formal change management system is useless, however, if the team is not committed to managing change. Project managers must set the expectation that all changes that can potentially affect the project baseline and task plans be communicated and analyzed for cost versus benefit. For distributed teams, it may make sense to establish a change management hierarchy where change is first managed locally, where the work is being performed. Then approved changes are communicated to the project-level change management body for ratification. Only changes that may affect the work of other team members or may affect the project baseline or success criteria need to go to the project level for evaluation. In practice, this is an effective model for collecting and analyzing change that is occurring remotely.

Establishing a Formal Process

The change management process itself is no different for a virtual project than for a traditional project. There is no shortage of materials available to help readers establish a process, so we will not add to the mountain of information. We do want to stress that project managers should strive for simplicity when establishing a change management process with a minimal number of steps. Seven steps are recommended:

- Submit a written change request.

- Evaluate benefit versus cost of the change.

- Assess impact of change.

- Make the change request decision.

- Log and communicate the change decision.

- Modify project and task plans based on approved changes.

- Communicate and implement the change.

For virtual projects, these steps will be performed with limited to no face-to-face discussions. It is important, therefore, to establish a dedicated change management team site for the project on the company intranet where fast and efficient communication related to various changes can occur. (See the box titled “Fast-Tracking the Change Process.”)

Communicating Changes

Finally, change decisions are of no value if they are not communicated to all those affected, especially virtual team members immediately affected by the change. Communication, always a critical factor in virtual project success or failure, is vital to ensure that changes that were approved and declined are communicated to the distributed workforce. Responsibility for implementing changes will likely fall on those performing project execution tasks in remote locations. Regular, specific, and formal change communication must come from the project change management body. The most effective means for communicating change decisions are the use of change management list servers and change management bulletin boards. (See Chapter 8.)

Additionally, communication of change should be incorporated into the project governance process. Each team should include information on changes approved and planned as part of their project indicator. Virtual project managers should, in turn, include baseline changes as part of their project dashboard and summary status report.

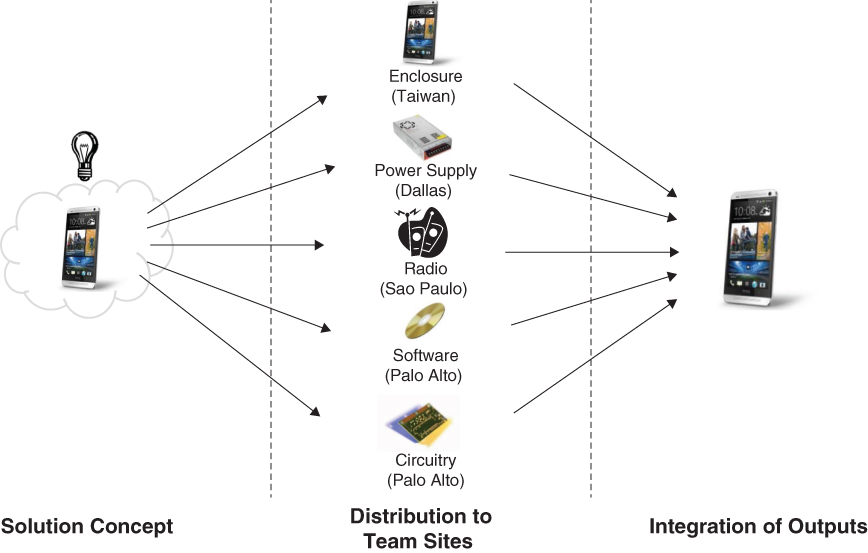

Integrating Distributed Work

An inescapable fact of virtual projects is that the various components of a project deliverable and final outcome are designed and developed in different locations.10 A significant portion of the execution stage of a virtual project involves the integration of the components into a holistic solution. (See Figure 4.5.)

Figure 4.5 Integration of Distributed Work Outcomes

Integration of the work outcomes and deliverables of localized teams is impossible if the work across the various locations of the virtual project is not occurring synchronously. In this regard, project managers are much like orchestra conductors. Even though each of the instrument sections of an orchestra has its own music to produce, the conductor ensures each section steps through the musical composition at a consistent tempo and in concert with each of the other sections. This ensures that an integrated, blended, and harmonious musical piece is produced.

Much is the same on a virtual project except for the fact that the players can be distributed around the world. Since the responsibility for managing the interdependencies between the geographically distributed team members falls on project managers, they must work to ensure that the work of each distributed team member occurs at an integrated and harmonious pace. Synchronization involves ensuring that timelines are aligned, that cross-project deliverables are planned and mapped appropriately, and that the work within each team is occurring at the appropriate pace.

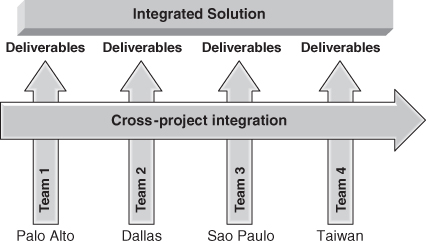

Managing Interdependencies

The disaggregation and reintegration of work is the centerpiece of integration and systems thinking. Virtual project managers oversee the disaggregation of the whole solution into a project architecture composed of multiple components. They then oversee the integration of work output from each of the components to create the consolidated whole solution. The true value and benefits of the project output can be realized only when the activities associated with each of the team members are integrated together into a holistic solution for the customer.11

Figure 4.6 Cross-Project Synchronization and Integration

Referring to Figure 4.6, we consider the horizontal dimension of a project as the synchronization of workflow across the team specialists. This synchronization is accomplished through cross-project interface definition, coordination of all project activities, collaborative communication on the project, and synchronization of the delivery of the interdependencies.

Although the role of localized teams is to manage the creation and delivery of their deliverables and outcomes, an important aspect of the integration role of virtual project managers is overseeing the handoff of deliverables between team members. This output-input relationship creates a network of interdependencies that has to be established and managed at the project level, not the local level.

Establishing the network of interdependencies is best accomplished through the practice of project mapping (see Chapter 3) and the creation of a project map. Project managers can use the map to manage the hand-off of cross-project interdependencies during the execution stage of the project.

Synchronizing Workflow

For effective integration to occur, synchronization of activities over time is necessary. However, for project managers, time management on a virtual project usually does not just involve managing the duration of tasks associated with each project component. Project managers who attempt to do so would be mired in detail. Rather, managing the project timeline involves ensuring the work outcomes and deliverables are occurring as planned and mapped.

Detailed schedule management is the focus at the local level, and summary, or integrated, time management is the focus at the centralized project level. This coordination requires a modular approach to time management where the schedule is disaggregated and partitioned according to where the work is to be performed. Schedule details for each component are worked by local teams and then integrated by project managers to gain the full perspective of the project timeline and critical synchronization points.

Virtual project managers should keep in mind that the most detailed schedule is not necessarily the best one. Too much detail can divert attention to one aspect of a project—the schedule—and away from the other critical aspects of managing a project and leading a team. If project managers focus on the critical synchronization points occurring over time and let local teams focus on the detailed schedule for their respective project components, a good balance for effective timeline management is achieved.

People Side of Project Execution

The mountain of literature that explains that most projects fail is discouragement enough to stop people from attempting to execute any project. The fact that the failure rate of virtual projects increases in relation to how distributed the virtual team is, puts virtual project managers under even more pressure to maintain diligence on the people side of project execution. Think about it. Here is the work (generally speaking) that project managers oversee during project execution:

- Manage planning assumptions while carrying out the integrated project plan to the realization of the value detailed in the business case and to the specifications in the scope document.

- Manage (in-sourced and outsourced) personnel, task assignments, deliverable hand-offs, and overall performance through tracking and monitoring systems.

- Establish and manage a rigorous governance system and facilitate status meetings and decisions ranging from staffing to task delivery to conflict resolution.

- Modify project details (schedule, budget, personnel, timing) as needed due to changes, risks, issues, and problems.

- Manage and integrate work of the project that is outsourced to other companies or subcontractors.

- Navigate team development from forming through storming and norming to high performing for the benefit of the existing project and future projects.

- Integrate the final product, service, or intended outcomes of the project.

All of this work occurs whether the project team is co-located or virtual. What is different when it comes to virtual project management, however, is the situational elements, the contextualization of the work, and how project managers and teams engage one another.

Not long ago, Sebastian Bailey, co-founder of Mind Gym, detailed the five killers in virtual work in a Forbes article.12 The five killers include:

- Lack of nonverbal, face-to-face communication

- Lack of social interaction among the team

- Lack of trust

- Cultural clashes

- Loss of team spirit

Clearly, each of these five killers of virtual projects has little to do with the blocking and tackling associated with basic project management practices. Rather, these killers all relate to the people side of a virtual team.

Moving from Storming to Norming and Performing

It is during the executing stage of a project that the full team is resourced and engaged in interdependent work. It's also during execution that project managers must lead the team from the forming stage of team development work to high performing.

Chapter 3 detailed the characteristics of a high-performing team. The five distinguishing factors of high-performing teams relative to other teams include:

- A deeper sense of purpose

- Relatively more ambitious goals

- Better work approaches

- Mutual accountability

- Complementary skill set (and, at times, interchangeable skills)

Achieving high performance is a challenge for even the most seasoned project managers. Conducting such work is much more challenging for managers overseeing virtual project teams.

Many of us are likely familiar with immersion programs. Whether it is a French immersion for a student from another country to become fluent in French and the French culture or a public safety community immersion in which police, fire, and other safety professionals purposefully immerse themselves in an area of the community to build awareness, establish common goals, build rapport, and establish trust. Immersion programs are similar in that they are strategies to quickly understand the community, align with its culture, and establish common ground and confidence. An immersion program would be great for virtual team development. Actually, nothing would be better. However, costs prohibit such a strategy for project planning and executing.

How can virtual project managers develop individuals and the team when they are not face-to-face and immersed with one another? The first step is to understand that project team member development is the responsibility and the challenge of project managers. Many project managers fail to realize their role in team development. Many assume this is the role of the human resources department or team members' direct supervising managers. Best-practicing project managers do indeed realize their role and, perhaps more important, realize the correlation between team development and project performance—from individuals to the collective team.

Beyond awareness of role responsibility, how does this development get done? First, let's start with how it doesn't get done. Team development success is not found in the latest technology. Sure, technology can be an enabler to team development, but often managers seek a technology solution when the problem is not a technology problem. Most problems associated with virtual project team development exist because of one of these reasons: (1) poor interpersonal skills, (2) lack of process discipline and consistency, or (3) team development is managed as an add-on rather than integrated into the team's work.

Based on these problems, the short answer for how best-in-class project managers develop their virtual teams is that they leverage interpersonal skills to know their team members and align developmental opportunities among team members, integrate team development into project work as an expectation and rule, and they spotlight individual knowledge in a way that enables everyone to teach others as much as they learn from others.

Team learning and team development is a social journey. Even if some individuals prefer self-directed learning and activities, they still learn from others in the process. For this reason, virtual project managers must establish a team culture of sharing lessons and best practices as a form of teaching and learning. The old Latin saying is true: “The best way to learn is to teach.”10

Why is this education so important during the executing phase of a project? For virtual teams, it's because of the need to be intentional and purposeful. Co-located project teams can get together (face-to-face) every week or so to review the knowledge area plans in a status meeting. During that meeting, team members can discuss risks relative to task-level work, milestones, and deliverables and how team members can support one another. They can also (face-to-face) sense frustration or conflict among one another and work through the conflict or schedule a separate meeting to resolve issues. In so doing, the team develops and naturally navigates the stages of team development. Additionally, being co-located allows team members to have coffee breaks together, or meet for lunch, and see what each other values; for example, displaying sports paraphernalia, family vacation photos, or other items in their cubicles allows others to see the personality of the person. All of this helps team members to get to know one another, understand one another, build trust and rapport, which cascades from personal awareness to team member camaraderie. These team member interactions all facilitate team development. Obviously, this rapport building is much more difficult among virtual team members. That's why virtual project managers have the additional role of intentionally seeking ways to build rapport within their virtual project teams.

Whether managers are leading a co-located or virtual team, they want the team to be high performing. It's from this point that collaboration occurs and further enables cross-team integration of work to be completed most efficiently and effectively. Listed in the box below are some additional suggestions from Dale Carnegie for leveraging the power of team members working together.

Influencing Virtual Stakeholders

The people side of project execution also includes the work virtual project managers perform associated with influencing a project's stakeholders. A stakeholder is commonly understood as anyone who has a vested interest in the outcome of a project. More important, for project managers, a stakeholder is anyone who can influence, either positively or negatively, the outcome of their project. This includes people and groups of people inside and outside the organization. Stakeholder management is a process with which project managers can increase their acumen in managing the political, communication, and conflict resolution aspects of their projects to ensure a positive outcome.14

Quite often, the accountability for project success relies more and more on the interpersonal abilities of project managers—those who have limited positional power within the organization yet still own the responsibility for project success. Project manager empowerment in part comes from building strong relationships and successfully influencing key stakeholders.15

Stakeholders are many and varied on projects, and they come to the table with a variety of expectations, opinions, perceptions, priorities, fears, and personal agendas that many times are in conflict with one another. One of the facts of virtual projects is that not all stakeholders are physically present and visible to project managers; nevertheless, they can exert significant influence over the project from afar. The challenges in working with stakeholders tend to increase in the virtual environment because of differences in language, time zones, cultural norms, and business practices (see the box titled “Managing Virtual Stakeholders).16 One virtual project manager we spoke with had an interesting perspective on virtual stakeholders:

The challenge, therefore, is to find a way to manage this cast of characters efficiently in a way that does not become all consuming. Fundamental to efficiency is being able to identify and separate the highly influential stakeholders and then create and execute a stakeholder strategy that strikes a balance between their expectations and project realities.17

Delegating Stakeholder-Influencing Duties

Due to the distributed nature of stakeholders on virtual projects, virtual project managers must rely on a number of their team members to share in the project stakeholder-influencing duties. In particular, project managers must tap influential team members who are geographically located near key stakeholders and can establish physical presence with them.

We must recognize, however, that virtual project team members are selected for their expertise in a particular specialty required for the project, regardless of their geographic location and their stakeholder-influencing capabilities.17

Selected team members must therefore concentrate on building collaborative relationships and alliances with their local stakeholder community. To do so effectively, the team members must be skilled in relationship building, stakeholder analysis techniques, and negotiating. In addition to distributed team members acquiring the necessary skills to influence project stakeholders, project managers must take care to choose team members who also possess an innate ability to communicate with people at all levels of the organization. Obviously not all team members will possess this innate ability or be able to acquire the skills necessary to influence others, so project managers must evaluate and choose stakeholder liaisons carefully. Once the liaisons are chosen, project managers also must take care to create an atmosphere in which team members are fully empowered to influence stakeholders on behalf of the project manager.

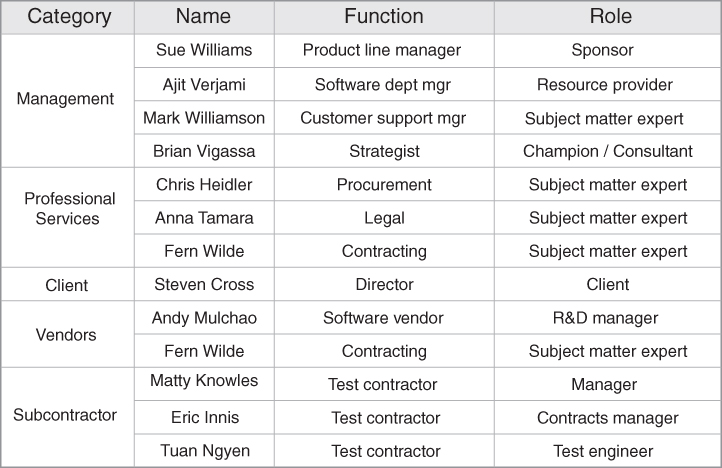

Instituting Common Methods and Tools

Since effective stakeholder management on a virtual project requires delegation of influencing activities to a number of project team members, it is essential that virtual project managers establish and oversee a common methodology and set of tools. This means there should be commonality in the way team members identify, categorize, and analyze key project stakeholders, regardless of geographic location.

Figure 4.7 Example Stakeholder Map in Table Format.

Source: Russ J. Martinelli and Dragan Z. Milosevic, The Project Management ToolBox, 2nd ed. (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley &Sons, 2016).

The primary goal of stakeholder management activities is to establish alignment to the strategic goals, intended business benefits, project objectives, and success criteria of a project.17 Unless there are only a very small number of project stakeholders, however, it is unrealistic to believe that there will not be conflicting opinions and interests between stakeholders. Such conflicts are common, and for this reason, it is important to develop a stakeholder strategy for the project to ensure that the right team members are influencing the right stakeholders. Developing a stakeholder strategy requires identifying all project stakeholders, analyzing the stakeholders' interest in and influence on the project, and then determining how to influence the key stakeholders.

Identifying Stakeholders

Effective stakeholder management begins with identification of all stakeholders associated with a project. It is important that the list of stakeholders be comprehensive to identify all players who may have a vested interest in the outcome of the project.

Regardless of whether the project team is co-located or virtual, when identifying stakeholders, it is important for project managers to cast a wide net, identifying all individuals and groups impacted by the project. The list of stakeholders will certainly include internal people, and also may include individuals and organizations beyond the boundaries of the organization. It is critical to think about the project impact relative to those in your supply chain and across your ecosystem.

Stakeholder identification also includes the categorization of stakeholders into the logical groups to which they belong. Such categories may include senior sponsors, executive decision makers, team members, and resource providers, to name a few. It is important to realize that some stakeholders may belong to multiple groups. The intent of stakeholder categorization is to bring structure to the stakeholder list based on common interests in the project.18

Tools such as stakeholder maps are common (see Figure 4.7) and can be effective in helping project managers identify the various stakeholders. The comprehensive stakeholder list should include internal stakeholders, such as top managers, project governance board members, department or functional managers, support personnel (accounting, quality, human resources), the project team, and any external organizations or contractors contributing to the project.

External stakeholders should also be listed and may include contractors, vendors, regulatory bodies, service providers, and others. The objective of stakeholder identification is to include anyone who might have an influence on the outcome of the project.

Analyzing Stakeholders

Project stakeholders can be many, dispersed, and varied in their viewpoints and characteristics. It is important for project managers to do a good job in identifying stakeholders, but stakeholder identification by itself has limited value. Developing a deeper understanding of project stakeholders' interests, opinions, and viewpoints is the necessary next step in the stakeholder management process. This step is commonly referred to as stakeholder analysis.

Stakeholder analysis activities involve determining what type of influence each stakeholder has on the project, such as decision power, control of resources, or possession of critical knowledge, and their level of allegiance to the project. In other words, would the stakeholder prefer the project to succeed, not to succeed, or is he or she indifferent about the outcome of the project?

The purpose of stakeholder analysis is to enable project managers to identify the individuals and groups that must be interacted with in order to accomplish the project goals. Effective stakeholder interaction is supported by thorough stakeholder analysis activities that allow project managers to develop a strategy to:

- Identify strategic interests that the various stakeholders have in the project to negotiate a common interest.

- Develop plans and tactics to effectively negotiate competing goals and interests between stakeholders.

- Secure active support from project champions. (See the box titled “What Is a Project Champion?”)

- Devise activities to neutralize or prevent the negative actions of nonsupporters.

- Allocate personal and expanded resources to engage with key stakeholders.

Many of the stakeholder analysis activities are about prioritizing project stakeholders. A small subset of stakeholders, commonly called key or primary stakeholders, possess a significant amount of organizational influence to either advance a project or inhibit its progress. Either way, these stakeholders have to be identified through a filtering and prioritization process. A stakeholder analysis table is an effective tool for analyzing the various project stakeholders. Table 4.2 provides an example.20

The table becomes the single source of information about the project stakeholders for further stakeholder analysis. To begin the analysis, project managers should use the information within the stakeholder analysis table to focus on four key pieces of information:

- Determination of the key project stakeholders.

- Assessment of stakeholder alignment to the project goals, scope of work, and project outcomes.

- Identification of potential conflicts of opinion between stakeholders.

- Identification of project advocates and nonsupporters.

It is far better to understand if stakeholders agree with the project goals identified and documented early in the project life cycle instead of waiting until it is too late to make adjustments to the goals or to work with stakeholders to get alignment.

Table 4.2 Example Stakeholder Analysis Table

| Name | Assumed Role | Expectations | Reservations | Provides to Project | Decision Control |

| Sue Williams | Sponsor | Project meets all business and execution goals | Firm's ability to develop the new capability | Direction and decisions | Gate approvals |

| Ajit Verjami | Department manager | No expectations for this project | Believes another project provides a better solution | Resources | Resource allocation decisions |

| Steven Cross | Client | Project will be completed under budget | Timeline is very aggressive | Funding | Gate approvals |

| Danielle Carvalho | Subject expert | Project will stay on schedule and complete on time | Already committed to two other projects | Time and expertise | None |

| … | … | … | … | … | … |

Virtual project managers cannot afford to be naive in thinking that all stakeholders want their project to succeed. Unfortunately, this is not always the case. Because of this, project managers can use the stakeholder analysis table to begin determining who the supporters and nonsupporters are. Specifically, close attention should be paid to the information that is contained in the “reservations” portion of the table. Typically, nonsupporters bring their reservations to light during discovery conversations with project managers. (See the box titled “Key Questions to Ask Stakeholders.”) Normally, an additional level of analysis is needed to determine if stakeholders who are not advocates may in fact become inhibiters to project success. However, at this stage, project managers should be able to separate advocates from nonsupporters. With information contained in the stakeholder analysis table in hand, project managers and their virtual stakeholder management proxies can begin to craft a stakeholder strategy for the project.

Creating a Stakeholder Strategy

Stakeholder analysis is about sense making. This means understanding the significance of the information gained about the various project stakeholders. Project managers then use the significance of the information to develop a strategy for engaging and managing the right set of stakeholders—those who have power and influence to affect the outcome of the project.

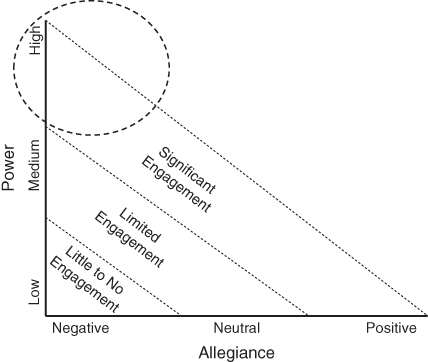

Most of the literature on stakeholder management classifies primary stakeholders as those with both high power and strong allegiance to the project. This is not completely accurate because it leaves out the most potentially dangerous stakeholders—those with high power and negative allegiance to the project. These people also need to be considered primary stakeholders. Figure 4.8 helps to illustrate why. Stakeholders with high power and negative allegiance require significant engagement.21

Figure 4.8 Power/Allegiance Grid

If project managers use the power/allegiance grid to map their stakeholders, a core stakeholder strategy will begin to emerge. The strategy should consist of a communication and action plan for each of the primary stakeholders. It should also keep the project advocates engaged, describe how they can be used to influence others, and plan how to win over or neutralize stakeholders who are not current advocates. The stakeholder strategy should consider:

- Which stakeholders require the most attention?

- Is there a need to influence a change of allegiance for any stakeholders?

- What message needs to be delivered to each stakeholder?

- Can any stakeholders be leveraged as champions?

- What is the best method and frequency of engagement and communication with each stakeholder?

- Does the strategy reflect the interests and concerns of each stakeholder?

The stakeholder strategy likely will identify the need to focus attention first and foremost on some of the most difficult stakeholders. Stakeholder engagement activities will test the courage of project managers who need to be brave and bold when faced with building relationships with stakeholders who are not fans of the project or may be professionally threatened by the project's outcome. Project managers must not follow the human tendency to avoid these stakeholders. Rather, they should seek them out and, most important, listen to what they have to say. Only by listening can project managers begin to find middle ground to use as a means to positively influence stakeholders.

I Forgot to Check the Box

All projects have both obvious stakeholders and nonobvious stakeholders. Because of the lack of physical presence between stakeholders residing at distributed sites, it is likely that more nonobvious stakeholders exist on virtual projects. Stakeholder identification, analysis, and strategy can only pinpoint needed actions for the obvious stakeholders. Surprises associated with nonvisible, nonobvious stakeholders are likely to occur, as they did for Jeremy Bouchard.

“I forgot to check the box that stated the product I was shipping to Japan for system testing was not for resale. Turns out that was a crucial oversight that had significant impact on the Sitka project. Because the product was in final prototype, it looked like a completed product that could be sold, even though it wouldn't perform like a completed product. The customs agent in Japan who inspected one of the products couldn't tell the difference by looking at it, and he therefore assumed it was not merely an engineering prototype, but could be sold. That raised his suspicion, and our systems test prototypes were quarantined in customs. Three weeks: That's what it took to submit the required paperwork, get it reviewed by Japanese customs, and get a decision to release the test prototypes from quarantine. Three weeks of lost schedule and project productivity. I learned that even a customs agent in a foreign country can be one of my project stakeholders—sight unseen.”

Assessing Virtual Project Execution

The virtual project execution assessment is really a readiness assessment that may be conducted several times during project execution. Depending on the duration and complexity of the project, project managers may want to conduct the first assessment 30 to 60 days after the start of executing. The reason for this is to make sure the team gets off to a fast and productive start, to ensure work plans designed in the planning phase are working properly in the executing phase, and perhaps to show early wins.

Additionally, the assessment may be used toward the end of the executing phase of work to ensure proper hand-off of project outcomes from the project team to the operations team. Again, depending on the duration and complexity of the project, project managers may conduct assessments 90 days prior to hand-off and then again at 30 and 60 days after hand-off. The goal of interval assessments such as these is to have the project managers, the team, and key stakeholders see “no” responses in the assessment moving to “yes” responses over time.

It is important to note that many of the assessment items are likely to yield a “no” response in the first 30 or 60 days of execution. That is intentional. For each “no” response, there should be an action plan and owner. It is a risk mitigation tactic to help the project manager ensure the project team has the resources and planning documents needed to achieve project success.

Virtual Project Execution Assessment

Project Name: _______________________________

Date of Assessment: ___________________________

Assessment Completed by: _____________________

Confidential Assessment: ______ Yes, confidential

______ No, not confidential

| Assessment Item | Yes or No | Notes for All No Responses |

| Resource Management | ||

| Financial resource needs are known, allocated, and appropriate for the successful execution of the project. | ||

| Personnel resource needs are known, allocated, and appropriate for the successful execution of the project. | ||

| Physical resource needs are known, allocated, and appropriate for the successful execution of the project. | ||

| Roles and responsibilities are documented. | ||

| Any impact on personnel resources has been planned with the office of human resources and strategies are agreed on. | ||

| Assumptions | ||

| Base assumptions from the outcome of planning are documented. | ||

| Each project assumption has an assigned validation owner. | ||

| All assumptions have been positively or negatively validated. | ||

| Risk events associated with untrue assumptions have been documented. | ||

| Stakeholders | ||

| All stakeholders (internal and external) have been identified. | ||

| A stakeholder assessment has been completed. | ||

| A stakeholder strategy has been developed and documented. | ||

| All team members with responsibility for influencing stakeholders have been notified and assigned specific stakeholders. | ||

| All team members with stakeholder responsibilities have been trained. | ||

| Governance | ||

| A project governance system has been established. | ||

| Monitoring and reporting expectations have been documented and communicated to the team. | ||

| A common status format and content has been established for distributed team members. | ||

| Distributed team leads are using a standard status indicator. | ||

| A project dashboard or equivalent tool is in use to track overall project status. | ||

| The project objectives are documented and are being monitored on a consistent cadence. | ||

| Project key performance indicators are documented and are being monitored. | ||

| Program reviews with senior leaders are being held at a regular cadence. | ||

| Change Management | ||

| All requirements have been detailed in a way that offers a solution that meets the organizational needs for the project and associated change. | ||

| Requirements are under change control. | ||

| A formal change management process is in place and in practice. | ||

| The organization has a culture that embraces change, but validates the need for change. | ||

| Change management protocols have been documented. | ||

| Changes are logged in a common database and change communication channels are established. | ||

| Changes are tracked and reported as part of the project governance system. | ||

| Additional Topics | ||

| Project managers and business personnel have discussed and planned for any integration conflicts with other projects and/or business initiatives. | ||

| Risks are identified and managed with clearly documented mitigation plans. | ||

| Communication processes, channels, and media are known for the project and are functioning effectively. | ||

| The implications of this project and associated changes to the rest of the organization have been communicated to the team. | ||

| Findings, Key Thoughts, and Recommendations | ||