11

Beyond Technology

In Chapter 2, the definition of systems was introduced together with a method to specifically demarcate them in their peculiarity in order to guide the analysis of their particular (physical) realizations. At this point, the fundamentals of the theory of cyber‐physical systems (CPSs) have been already presented, together with more practical examples and the description of the key enabling information and communication technologies (ICTs). What is still missing is the necessary articulation of the technical dimension as part of the social whole. The determination of a particular system by explicitly considering its conditions of reproduction and external conditions allows the CPS designer or analyst to define the level of effectivity of aspects beyond the technical development itself.

CPSs do exist materially in the world to perform specific functions. They affect, and are affected by, existing social practices; they may also create new practices, possibly modifying some aspects of society by reinforcing or challenging them. For example, during the decade that started in 2011, the growth of social media interactions, the widespread of high‐speed mobile Internet and the development of algorithms for pattern recognition have produced changes in established political and economic practices (e.g. [1]). These effects are far from linear and can be seen as part of the different CPS self‐developing reflexive–active dynamics that are relatively autonomous, but not at all independent of the world external to them. Although it would be impossible to provide a complete account, there are some aspects that are indeed more general and far‐reaching, and thus, much more likely to produce real effects in the CPS design, deployment, and operation. This chapter critically discusses these aspects.

11.1 Introduction

It is unquestionable that we all live under the capitalist mode of production. Despite all ideological prejudice and political propaganda, Karl Marx is still fundamental to scientifically understand the complex exploitative dynamics of the modern society based on historically determined social forms. This theory was introduced in his magnum opus Capital [2], whose first words are:

The wealth of societies in which a capitalistic mode of production prevails, appears as a 'gigantic collection of commodities' and the singular commodity appears as the elementary form of wealth. Our investigation begins accordingly with the analysis of the commodity.

Capitalism is a specific mode of production that is built upon the commodity form: the abstract concept that apprehends the reality of Capital; it is the elementary aspect of Marx's theory and of the actual capitalist social formations themselves [3]. Throughout thousands of pages, Marx produces a scientific theory (abstract theory) of society based on specific concepts and social forms (i.e. concrete abstractions), which serve as the scientific frame to assess any capitalist social formation. In particular, the text consists of several concrete examples of then existing social formations, notably England.

Against certain dogmatic and idealist readings of Marx, the philosopher Louis Althusser returns to the mature Marx of Capital considering it as the beginning of the science of history, i.e. the history punctuated by different dominant modes of production [4]. Although the discussions within the Marxist tradition and the critiques toward (academic and political) Marxism are very far from the scope of this book, I consider impossible to not move in this direction because the theoretical readings of Althusser, systematized mainly in [5], are the most suitable way to conceptualize the mutual effects between technology (including CPSs) and other aspects beyond the social whole.

In Althusser's words, the society is a complex whole articulated in dominance where the economic relation is the determination in the last instance. This means that, in the capitalist mode of production, the social phenomena are always affected by the commodity form, which organizes at some level the existing social relations and practices. In plain words, capitalism is a society of commodities where every single aspect of the world, not only including man‐made things and processes but also the environment, animals, and humans with their labor power is a potential commodity to be produced, exchanged, exploited, accessed, or sold, aiming at the perpetual self‐growth of capital (an unlimited abstract ending in itself). Note that this is not a reductionist argument, but rather acknowledges that in capitalism money talks.

This apparent digression is needed because CPSs are a result of the technical‐scientific developments of capitalism, and thus, an articulation with the realities outside their boundaries must consider this fact. We actually have implicitly considered this when we have indicated, for example, that the existence of a given CPS requires maintenance, technical development, education, and trained personnel as conditions of reproduction or external conditions because, in capitalism, they are all related to the availability of funding, cost‐benefit analysis, potential for profit, return of investment, and so on. Our role as a CPS designer or analyst is to properly articulate how those needs that are not technical in a strict sense are related to particular CPS technologies and their technical operation. One of the aspects is the governance model that implicitly or explicitly affects the design and operation of CPSs.

11.2 Governance Models

Governance is defined as [6]: the act or process of governing or overseeing the control and direction of something (such as a country or an organization). In 2009, the Nobel prize in economics was awarded to Elinor Ostrom for her analysis of economic governance, especially the commons [7]. Her main contribution is to prove that the usual economic classification that divides governance models into two mutual exclusive possibilities, namely the market‐based model from the (neo)liberal theory and the state‐based model based on the centralized planning optimization, is not sufficient and is indeed misleading [8, 9]. A commons‐based governance model is then presented as an existing third option where specific norms are set by the users of a given shared resource themselves in order to define the way to manage its use.

Although most of her studies focused on special cases concerning communities and their respective environment to produce a social‐ecological system [10], the categorization of governance models proposed by Ostrom is also suitable for the study of CPSs. In particular, CPSs are self‐developing reflexive‐active systems that operate under a specific governance model that might also determine the approach taken in their operation by affecting the internal decision‐making processes. In the following subsections, a brief overview of the three (ideal) types of governance models and their impact in (and on) the operation of CPSs will be provided.

11.2.1 Markets

Market‐based governance models presuppose that potentially everything (goods, services, persons, working power, etc.) can be commodified. In order words, they assume the existence of sellers who have property rights of the commodity ![]() and buyers who are willing to spend money to acquire some rights of

and buyers who are willing to spend money to acquire some rights of ![]() . The price of

. The price of ![]() will be defined by the balance between the aggregate supply and demand of that commodity. The market relations are mostly studied by microeconomics supported by neoclassical economic theory, which strongly relies on mathematization.

will be defined by the balance between the aggregate supply and demand of that commodity. The market relations are mostly studied by microeconomics supported by neoclassical economic theory, which strongly relies on mathematization.

Despite its elegance, such a theory is built upon very strong (unsound) assumptions of how the real interactions actually happen. These assumptions are that economic decision‐makers/agents [11]: (i) can identify, quantify, and prioritize their individual choices without internal contradictions; (ii) always aim at maximizing their individual utility or profit; and (iii) are independent of one another and have access to all relevant informative data at the time of their (synchronous) decisions. The neoclassical theory mathematically proves that if those arbitrary axiomatic assumptions hold, the competitive market structure always leads to the most efficient allocation of ![]() in the terms defined by the theory itself.

in the terms defined by the theory itself.

This result is the main strength and the main weakness of this way of theorizing social‐economic phenomena. As a theory itself, its scientific value to apprehend the reality of economic processes is highly questionable because its main assumptions are empirically inconsistent with its object, despite the mathematical formalism and correctness. On the other hand, neoclassical economy provides a clear technical knowledge to guide and justify decision‐making processes: it has a heuristic value to intervene in the reality it claims to produce the truth of. This interventionist rationality affects the design of policies and technologies alike.

A market‐based governance model then shapes the conditions of reproduction and external conditions of CPSs through the assumption that CPSs are commodities themselves and/or produce commodities. In other words, the constitutive relations of CPSs are at some level mediated money (the universal equivalent) allowing exchanges of property rights determined by private law and contracts between free subjects of law; all these are valid and guaranteed by the state power. Note that property rights are different from, although related to, possession. The first depends on a third element – the state (or perhaps a blockchain) – to enforce the contracts between subjects of law (or of new ICT systems); property is then mediated and refers to the ownership guaranteed by a third party (or by a specific ICT system design). Possession, in turn, is related to the direct use or consumption of a specific thing, good, or process. The following example illustrates how the market‐based governance model affects the operation of a specific CPS.

Today, the market‐based governance model is almost a natural choice because prices are always given and universal. In practice, the problems of the unsoundness of neoclassical theory are solved by particular institutional designs and technical interventions, as well as education to produce the rational human beings axiomatically defined by the theory. There have been several studies (including several Nobel prizes) that have tried to correct the assumptions of neoclassical theory; the reader is referred to the last chapter of [11] for some examples. One remarkable and very pragmatic approach is to consider the market economy as a multiagent complex system. The engineer–economist W. Brian Arthur is probably the best‐known author in the field called Complexity Economics, whose main principles have been summarized in [16].

The heuristic value of Complexity Economics, heavily supported by the advances in computer sciences and ICTs, does not change the core of neoclassical theory. Markets are theoretically studied based on universal rules of behavior and concretely deployed through enforcement of contractual rules (or private law). The freedom of market relations is bounded by those types of rules that define the possibilities that individuals have (even if they are heterogeneous and have access to different sources of information); in this sense, individuals become subjects to the given rules (or to the law). Because individuals cannot (directly) deliberate about (abstract) rules that affect their relations with each other, their autonomy is (strongly) bounded. Nevertheless, there is a certain level of autonomy where individual decision‐makers are usually agents, making the market‐based governance model associated with a distributed topology of decision‐making process and action. In the following section, we will move to another governance model related to the centralized approach of planning, where the autonomy in decision‐making is further limited but, counterintuitively, opening the possibility for more effective individual and social outcomes.

11.2.2 Central Planning

In contrast to the market‐based governance model where decision‐makers are considered independent and formally equal in relation to the rules, central planning is fundamentally grounded in an asymmetry in the decision‐making process. In this case, there is one central decision‐maker that sends direct commands to agents. This centralized approach provides a straightforward way to coordinate agents because the decision‐maker can produce a schedule of actions to be taken by them. Central planning usually refers to disciplines of operational research and systems engineering [17].

Such a governance model is, nonetheless, fully integrated into the capitalist mode of production and the commodity production. In fact, the Fordist regulation of the period usually called golden years of industrial capitalism has been strongly related to centralized planning and hierarchical decision‐making [18]. Despite its key differences from the post‐Fordist regulation (which is related to decentralization of operations toward a market‐based governance model), central planning is not opposed to the capitalist social forms but it assumes a rigid technocratic distinction between the elements of the system: one capable of “thinking” and planning (the decision‐maker) and several others of “doing.” A one‐to‐many topology where one element controls and all others follow its direct orders directly emerges from that.

In CPSs, this is reflected in situations where there is only one element that is a decision‐maker orchestrating actions in order to reach the optimal operation of the system considering some performance metric to be optimized. This approach is usually operationally driven, and thus, the effectivity of the CPS to perform its peculiar function is put at the center of the optimization problem. This generally leads to maximization problems related to a utility that captures the efficiency of the CPS to accomplish its operational function. It is also possible that, like in market‐based governance models, price signals are used to make decisions and guide actions, aiming at profit maximization or loss minimization. In this situation, however, the market price is given as an external signal, and the goal of price is not to balance supply and demand that are internal to the CPS (in contrast to the market‐based governance approach when it is internally used by distributed decision‐makers). In the following, an example of central planning in a cyber‐physical energy system will be provided.

Despite the differences between the two governance models, this example indicates that, in the capitalist mode of production, central planning is subordinated to market imperatives (e.g. maximizing profit or improving cost‐efficiency). However, in central planning, price signals are used only as an external input for the optimization procedure, which organizes the agents' interventions. In any case, depending on the CPS under consideration, a central planning governance model might be used to prioritize operational aspects of the system self‐development rather than internalize price signals as information to be used by distributed decision‐makers to decide about their actions, creating the possibility of collective effects. On the other hand, network topologies that rely on central elements are more vulnerable to targeted attacks.

Nevertheless, most large‐scale CPSs like cyber‐physical energy systems and industrial CPSs are neither completely distributed nor completely centralized in their decision‐making processes. Therefore, they can be assessed by systematically studying their own peculiar functions and the complex articulations between the specific CPS and the environment in which it exists, which is also composed of other systems (cyber‐physical or not). As the two examples presented so far indicate, in capitalism, the articulation between the CPS and the economy shall always be considered, either operationally or as an external condition. Following the groundbreaking empirical research of Elinor Ostrom [8] about the commons and the theoretical contributions by Karl Marx [2], the next subsection focuses on a different mode of production that exists at the margins of capitalism but that offers an alternative to the commodity form following commons‐based peer production [19].

11.2.3 Commons

The commodity form as a universal abstraction necessarily supported by the state power and by a legal system nucleated around private law is very recent in history [2, 19]. In 2021, the tendency of commodification of every possible aspect of reality is probably stronger than ever, enclosing not only physical spaces but new cyber‐physical ones. Opposing it and, at the same time, opposing a centralized state power to command the access of shared good, processes, and environments (being them physical or cyber‐physical) [9], Ostrom et al. studied the commons as a type of governance used in several communities that shared common resources (e.g. fisheries); her work is so remarkable that she won the Nobel prize in economics for her studies.

The term commons refers to a shared resource that needs to be managed to avoid overutilization, which may harm its existence. In her empirical study of local communities, Ostrom showed peculiar institutional arrangements produced by the members themselves to (self‐)govern the shared pool of resources, summarized in eight principles [Table 3.1][8] (with modifications indicated by [![]() ]):

]):

- Clearly defined boundaries (…)

- Congruence between appropriation and provision rules and local conditions (…)

- Collective‐choice arrangements [where] most individuals affected by the operational rules can participate in modifying the operational rules.

- Monitoring (…)

- Graduated sanctions [where] appropriators who violate operational rules are likely to be assessed graduated sanctions (depending on the seriousness and context of the offense) by other appropriators, by officials accountable to these appropriators, or by both.

- Conflict‐resolution mechanisms [where] appropriators and their officials have rapid access to low‐cost local arenas to resolve conflicts among appropriators or between appropriators and officials.

- Minimal recognition of rights to organize [where] the rights of appropriators to devise their own institutions are not challenged by external governmental authorities.

- Nested enterprises [for larger systems where] appropriation, provision, monitoring, enforcement, conflict resolution, and governance activities are organized in multiple layers of nested enterprises.

Ostrom's approach is empirical in the sense that it identifies institutional principles that exist in communities that share a resource among their members. Her work is also normative because these principles are associated with appropriation rules that govern a common pool of resources (i.e. the commons) without being guided by market‐based or central‐planning‐based governance models. More interestingly, such an institutional‐normative solution is not universal and depends on the resource under consideration; it is also based on possession and not on private property or a universal legal system. In other words, the commons is, in principle, not subordinated to the commodity form. Despite its importance, Ostrom did never foresee it as the basis of a new mode of production.

Other authors, in their turn, were motivated by her work to find alternatives to capitalism. Specially with the development of the Internet together with new forms of peer production and distribution of cyber goods such as Wikipedia, Linux, and BitTorrent, the potential of new more participatory technologies was identified as the seed of a new society [20]. From those ideas, Bauwens et al. defended in [19] a new mode of production based on peer production and peer‐to‐peer (P2P) exchanges where resources are shared in a common pool. In their own words:

P2P enables an emerging mode of production, named commons‐based peer production, characterized by new relations of production. In commons‐based peer production, contributors create shared value through open contributory systems, govern the work through participatory practices, and create shared resources that can, in turn, be used in new iterations. This cycle of open input, the participatory process, and commons‐oriented output is a cycle of accumulation of the commons, which parallels the accumulation of capital.

At this stage, commons‐based peer production is a prefigurative prototype of what could become an entirely new mode of production and a new form of society. It is currently a prototype since it cannot as yet fully reproduce itself outside of mutual dependence with capitalism. This emerging modality of peer production is not only productive and innovative 'within capitalism,' but also in its capacity to solve some of the structural problems that have been generated by the capitalist mode of production. In other words, it represents a potential transcendence of capitalism. That said, as long as peer producers or commoners cannot engage in their self‐reproduction outside of capital accumulation, commons‐based peer production remains a proto‐mode of production, not a full one.

As indicated above and exemplified by the very examples of the Internet (Wikipedia, Linux, and BitTorrent) or more recent ones like Bitcoin, commons‐based peer production, and P2P exchanges can be (and are) subordinated by the commodity form as far as the dominant mode of production is (still) capitalism. However, the proposed concept of cosmolocalism that would arise from the commons as a foundational social form based on peer production and shared appropriation of resources provides another way to design CPSs. In this case, price signals are excluded from the CPS self‐developing operation while trying to isolate it from the commodity form. In other words, whenever possible, the CPS design and operation shall avoid market relations that should be kept at the minimum level as part of its external conditions. An example of a commons‐based cyber‐physical energy system as proposed in [21–24] will be presented next.

The most interesting aspect of commons‐based governance models is the decentralized, yet structured, nature of the decision‐making process focusing on the use or appropriation – and not the property – of a given shared or peer‐produced resource by agents considering their needs. On the other hand, large‐scale CPSs governed as a commons need all types of support, such as technical, financial, and scientific, to be able to sustain their existence at the margins of capitalism. Nevertheless, as pointed out in [19], such designs might be part of a new society based on sharing, constituting then a new mode of production based on the commons. In this case, the capitalist mottoes would change to unlock the access and create a new commons.

11.2.4 Final Remarks About Governance Models

This section provided a very brief review of three types of governance models and how they can potentially affect CPSs. It is noteworthy that not all CPSs are equally impacted by the governance model, but they are all at some level subjected to it. We have illustrated three examples based on cyber‐physical energy systems where market‐based, central‐planning‐based, and commons‐based approaches are internalized in the system self‐development. The objective is to indicate the importance of the governance models when analyzing and designing CPSs, not only neglecting them or considering them as something irrelevant or independent. The core argument is that the governance model is both (implicitly or explicitly) constitutive of the CPS design and (indirectly or directly) articulated with its operation. The reader is invited to think more about it in Exercise 11.1.

11.3 Social Implications of the Cyber Reality

This section presents different emerging domains where the cyber reality, which is intrinsic of CPSs, has been disruptive in social terms. The topics covered are: data ownership, global platforms, fake news, and hybrid warfare. They are clearly interwoven, but it is worth discussing them individually and in this order. The rationale is that data regardless of the legal definition of their ownership are usually associated with global platforms that possess hardware capabilities for data storage and processing in huge data centers, cloud servers, and super computers. Processed data usually produce semantic information, which can be manipulated to become misinformation – part of this phenomenon is today (in 2021) called fake news. The widespread of fake news is analyzed by several authors as part of military actions, creating hybrid warfare associated with geopolitical movements.

11.3.1 Data Ownership

As mentioned in the previous section, capitalism depends on private property defined by legal rights, in contrast to direct appropriation and possession. When this is related to a concrete thing ![]() , it is easier to indicate the ownership. For instance, a house

, it is easier to indicate the ownership. For instance, a house ![]() , which is in possession of a person

, which is in possession of a person ![]() , is legally owned by a bank

, is legally owned by a bank ![]() ;

; ![]() is allowed to use

is allowed to use ![]() following the contract signed with

following the contract signed with ![]() . The cyber domain brings new challenges: who is the owner of data (as a raw material) and information (as processed data)? Are data owned by the one who acquires them? Or the one who legally owns the hardware used in the data acquisition? Or even the one who stores and processes the data? The following example illustrates these challenges.

. The cyber domain brings new challenges: who is the owner of data (as a raw material) and information (as processed data)? Are data owned by the one who acquires them? Or the one who legally owns the hardware used in the data acquisition? Or even the one who stores and processes the data? The following example illustrates these challenges.

This example points to the challenges that the cyber reality brings in a mode of production where informative data are commodified, and in this case, can be traded after being processed. Thus, a definition of data ownership becomes necessary. This is, in fact, an ongoing discussion, and different national states are legislating their own solutions. So far in 2021, the most remarkable legal definition is probably the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) [29, 30] defined by the members of the European Union. Without discussing the details, GDPR aims at offering more rights to legally defined individuals to control their data in order to facilitate business operations of corporations in a world increasingly composed of CPSs. Although this, in principle, complies with the idea of empowering people's control over their data, the actual results might be different because most data processing power is located in very few profit‐driven global platforms.

11.3.2 Global Platforms

There is only a handful of private enterprises that own large‐scale platforms (i.e. hardware – data centers and super computers – logically connected through the Internet) that are employed to store and process the (big) data acquired worldwide [31]. Furthermore, these platforms offer widely used services and applications like emails, calendars, and text editors and, at the same time, enable third parties (being them other companies, governmental agencies, or individuals) to run their own applications. As their name already indicates, platforms are deployed to serve as a shared infrastructure (forming, in the current business language, ecosystems) where different applications coexist and run. Therefore, they are nowadays essential for CPSs to exist and operate.

The importance of such global platforms in the world of 2021 is unquestionable, and their economic, social, and political powers are growing steadily (the reader is referred to [32], for example). There are already uncountable issues related to political interventions, prejudice, data leak, and service outages. The strong dependence of fundamental aspects of society – including applications related to CPSs – on very few for‐profit platforms is problematic. The book [33] presents several examples of such problems; actually, the main claim is that they tend to be a rule rather than only exceptions. Some other issues have been reported in [34], considering personal assessments during the growth of one of the largest global platforms that exist at the moment when this book is being written. One remarkable problem of today's Internet very related to social media controlled by such platforms refers to the phenomenon of fake news.

11.3.3 Fake News

Traditional media channels such as newspapers, radio, and TV have been (correctly or incorrectly) considered reliable sources or curators of news (or in our wording, informative semantic data). With the widespread of the Internet and the emergence of platforms, every user is a potential producer of content, including data that might be (intentionally or not) incorrect, i.e. a source of misinformation or disinformation. This characterizes the context in which the term “fake news” has been defined. The reference [35] presents a definition of fake news that is reproduced next.

We define “fake news” to be fabricated information that mimics news media content in form but not in organizational process or intent. Fake‐news outlets, in turn, lack the news media's editorial norms and processes for ensuring the accuracy and credibility of information. Fake news overlaps with other information disorders, such as misinformation (false or misleading information) and disinformation (false information that is purposely spread to deceive people).

Fake news concern the domain of semantic data, bringing more uncertainty in existing structures of meaning. The key problem is that, as mostly discussed in Chapters 3 and 4, uncertainty can be only studied with respect to some givens (i.e. well‐determined structures of assumptions, which can vary, but these variations shall also be well determined). If this is not the case, then the uncertainty assessment becomes unfeasible to decision‐makers. This phenomenon was described in detail in a recent report by Seger et al. [36], which also proposes ways of promoting epistemic security in a technologically‐advanced world.

In this sense, the epistemic insecurity caused by disinformation attacks against stable structures of semantic information seems to be the function of fake news. However, it is very unlikely that this is something that has emerged spontaneously in society, but rather it seems to be closely linked to two interrelated trends of today's society, namely cyber‐security (and the large business behind it) and hybrid warfare (and the geopolitical rearrangements after the Cold War, the 2008 economic crisis, and the emergence of global platforms among other relevant issues).

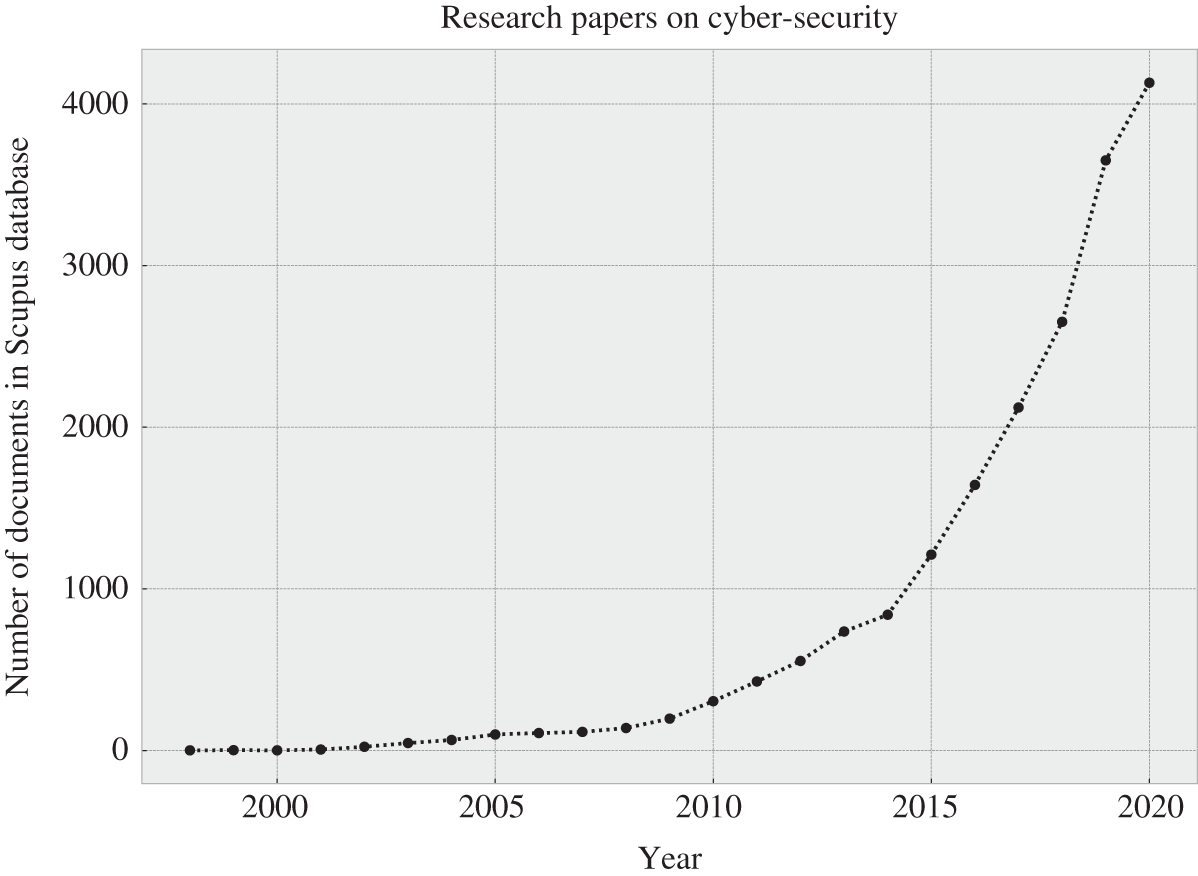

Figure 11.2 Number of publications in the Scopus database containing the term “cyber‐security” or “cybersecurity”.

11.3.4 Hybrid Warfare

With the widespread of CPSs, security issues are increasingly moving from physical attacks toward cyber attacks. Just as an illustration, we have plotted the number of research articles published from 1980 to 2020 containing the words: “cyber‐security” or “cybersecutiry.” Figure 11.2 indicates an exponential‐like growth, remarkably after 2015.

Despite the recent general interest, the research in cybernetics has always been associated with security and military applications since the Cold War years [37–39], leading to two traditions – one from the USA another from Russia – whose principles are remarkably similar.

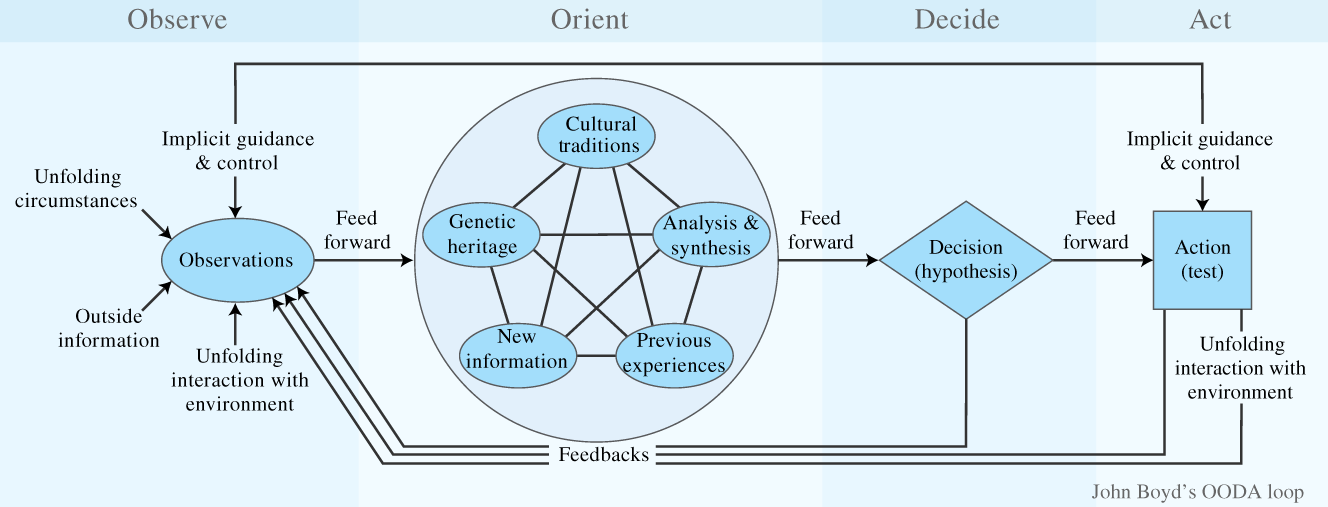

In the USA, the cybernetics ideas for the military can be framed by the observe–orient–decide–act (OODA) loop described by United States Air Force Colonel John Boyd [40], which was influenced by the US‐based cyberneticians like Nobert Wiener. Figure 11.3 depicts the OODA loop, where observations provide informative data for orientation that are then used for decisions about actions. Note that the OODA loop approach is similar to the 3‐layer CPS concept defined in Chapter 7. For Boyd, the warfare should involve operations in the OODA loop by, for example, injecting intentionally false semantic data (i.e. disinformation of a cyber attack) or sending electromagnetic signals to disrupt transmissions (i.e. physical cyber attacks). By purposefully affecting the OODA loop, the attacker might be capable of producing the desired results without physical battles, bombing, or other military interventions. The best analysis of the contribution of Boyd to contemporary military thinking is provided in [40].

Figure 11.3 Boyd's OODA loop.

Source: Adapted from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/OODA_loop.

On the Russian side, the research field is called reflexive control, defined as [41]: a means of conveying to a partner or an opponent specially prepared information to incline him to voluntarily make the predetermined decision desired by the initiator of the action. The idea of reflexive control started in the 1960s with [42], already discussed in Chapter 7, and it is still an active field nowadays developed as part of the third order cybernetics research activities [43]. The first military researcher outside the former Soviet countries to pay attention to this methodological way to approach warfare was the already retired Lieutenant Colonel Timothy Thomas from the US Army [41] in an attempt to better understand the military thinking in Russia after the Cold War. In a recent monograph, Major Antti Vasara from the Finnish Defense Force [44] revisited the Russian reflexive control in an attempt to bring more light to the different military operations (fairly or unfairly) imputed to today's Russia.

Although it is unfeasible to delve deeper into this topic, which is also blurry because of the nature of military conflicts themselves, the ICT‐based, CPS‐based warfare is pervasive, including relations to uprisings and conflicts worldwide. The term hybrid warfare is usually employed to characterize the nature of these conflicts. In a policy brief What is hybrid warfare? we read [45]:

Various characteristics have been attributed to HW [hybrid warfare] conducted by non‐state actors. First, these actors exhibit increased levels of military sophistication as they move up the capabilities ladder, successfully deploying modern weapons systems (like anti‐ship missiles, UAVs), technologies (cyber, secure communication, sophisticated command and control), and tactics (combined arms) traditionally understood as being beyond the reach of nonstate adversaries. Combining these newly acquired conventional techniques and capabilities with an unconventional skill set – and doing so simultaneously and within the same battlespace – is seen as a potentially new and defining characteristic of non‐state HW. This emphasis on greater military sophistication and capabilities is one of the key features of non‐state actors using HW.

A second core characteristic of non‐state HW is the expansion of the battlefield beyond the purely military realm, and the growing importance of non‐military tools. From the perspective of the nonstate actor, this can be viewed as form of horizontal escalation that provides asymmetric advantages to non‐state actors in a conflict with militarily superior (state) actors. One widespread early definition of HW refers to this horizontal expansion exclusively in terms of the coordinated use of terrorism and organized crime. Others have pointed to legal warfare (e.g. exploiting law to make military gains unachievable on the battlefield) and elements of information warfare (e.g. controlling the battle of the narrative and online propaganda, recruitment and ideological mobilization).

(…)

The single critical expansion and alteration of the HW concept when applied to states is the strategically innovative use of ambiguity. Ambiguity has been usefully defined as “hostile actions that are difficult for a state to identify, attribute or publicly define as coercive uses of force.” Ambiguity is used to complicate or undermine the decision‐making processes of the opponent. It is tailored to make a military response—or even a political response–difficult. In military terms, it is designed to fall below the threshold of war and to delegitimize (or even render politically irrational) the ability to respond by military force.

It is clear that the description of hybrid warfare fits well with the development of both CPSs for military functions and for the use (and abuse) of the new opportunities that the cyber domain opens to new types of attacks. Disturbances in elections, military‐juridical coups, and civil wars employing epistemic insecurity as a military tool are related to the new economic powers and geopolitical movements in the post‐Fordist time we currently live in [1]. All these rearrangements in the economic and (geo)political power associated with the emergence of global platforms can be seen as a social impact of CPSs as part of the capitalist mode of production. The new technologies do work, but their effects beyond technology can lead to consequences that increase the exploitation of work and nature, reinforce existing oppressive relations, and support new types of military operations.

11.4 The Cybersyn Project

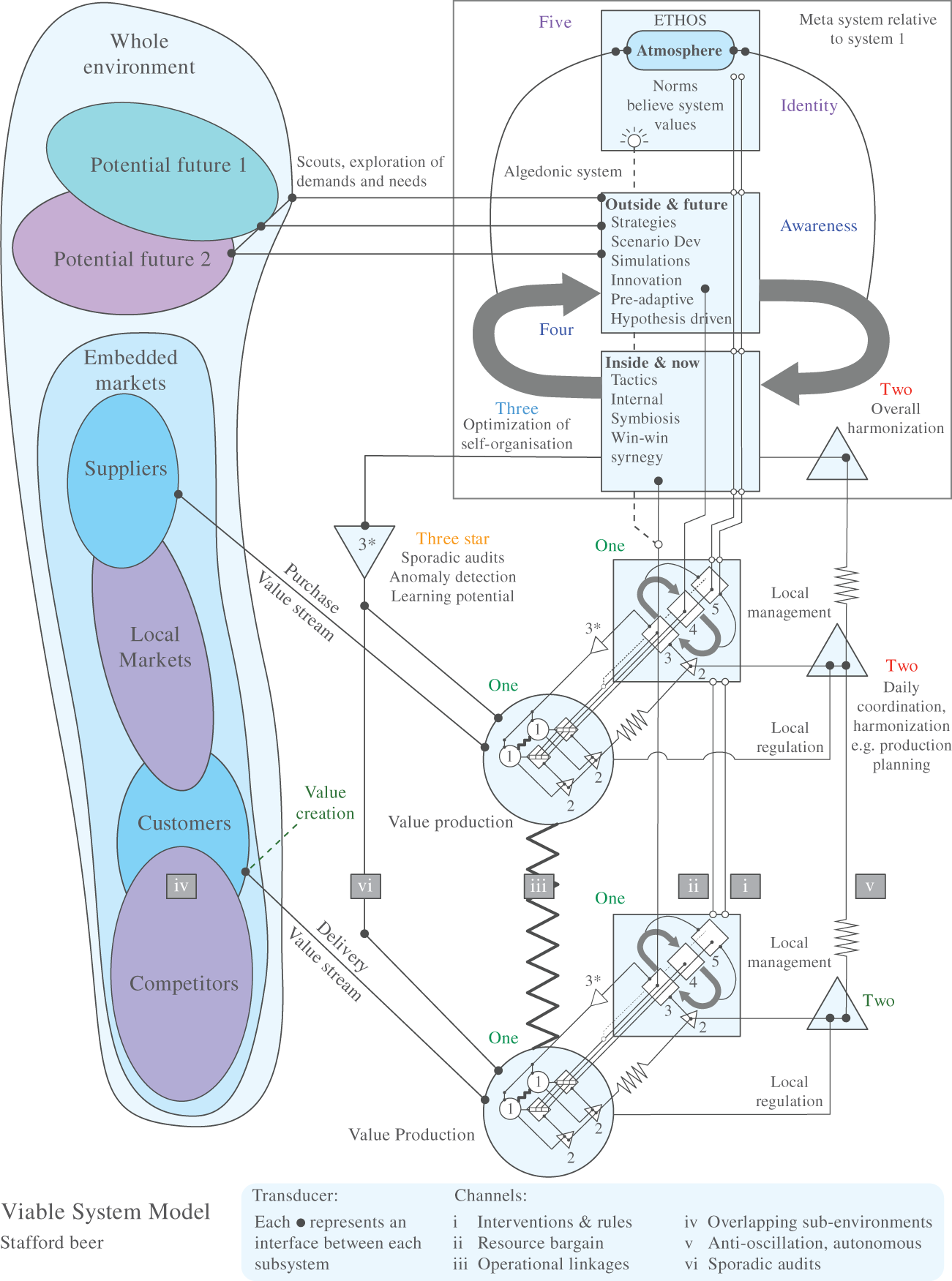

To end this chapter, a remarkable – and not well known – historical fact will be briefly introduced: the never realized cybernetic management of the Chilean economy. In the early 1970s, the democratically elected president in Chile, Salvador Allende, started the implementation of a distributed decision system to support the management of the Chilean national economy. The leader of the project was the recognized British researcher Stafford Beer, who first developed the field of cybernetic management by constructing the viable system model (VSM) [46]. Figure 11.4 illustrates a case of the VSM for the management of a socioeconomic scenario. The main idea is to incorporate both physical and information flows to operate and manage (sub)systems and their relations to viably perform their functions in a resilient way because the VSM is designed to be adaptive with respect to changes in the environment. In other words, the VSM sees (sub)systems forming as an organic, cybernetic whole (a system of systems).

Despite the active participation of unsuspected researchers, universities, and companies from the USA and England, the Cybersyn project had the same fate as president Allende: a victim of the Cold War and the fight against socialism in Latin America. The plan of creating a communication network and a decision support system to manage the Chilean economy in a distributed manner failed for reasons beyond technology. Chile paid the price of the geopolitics of the 1970s, and the ICT development to produce the social impact needed in Chile never took hold. Instead, in contrast to the economic plan for social development to produce a fair society, the military coup implemented (neo)liberal economic policies by force, making the Chile under the military dictatorship a laboratory of today's mainstream approach to the economic policies.

An important historical account in the complex relation between technology and other social processes is presented in [47]. The lesson to be learned is that technological development is far from being neutral, as already indicated by Marx [2] and further developed by Feenberg [20]. The design, operation, and actual deployment of technical systems are always subject to power relations, mainly economic, but also (geo)political and social. The story of the Cybersyn project makes very clear the challenges ahead if one acknowledges that the vision of a society dominated by the (peer‐produced) commons to be shared and managed by CPSs is, in many ways, similar to the cybernetic economic planning envisioned by Beer and Allende.

Figure 11.4 Example of Beer's VSM.

Source: Adapted from: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/b/b6/VSM_Default_Version_English_with_two_operational_systems.png.

11.5 Summary

The theory constructed throughout this book allows the incorporation of aspects beyond technology following the indications of the critical theory of technology developed by Feenberg [20]. Instead of illustrating the positive aspects of CPSs, which are fairly well known and advertised, we rather prefer to question the mainstream assumptions of technological neutrality that are narrowly evaluated by economic benefits. The main argument is that CPSs can be designed to not be subordinated to the commodity form, and thus, they can be used to govern the use of shared resources without market mediations by opening access and then creating new commons. Furthermore, the social impact of the new ICT technologies has been reviewed by discussing aspects related to data ownership, global platforms, fake news, and hybrid warfare. The list is not supposed to be extensive; it only serves as indications of the challenges of the society we live in, its limitations, and potentialities. We need to move beyond the capitalist realism [48] in order to build new ways of living with CPSs aiming at a future society based on sharing and without exploitation.

Exercises

- 11.1 Different governance models in CPS. Choose a CPS of your interest.

- Demarcate the CPS based on its peculiar operation and its conditions of existence.

- Indicate how the three types of governance models presented here can affect the selected CPS.

- Identify one benefit and one drawback of the three governance models with respect to this CPS operation.

- Write about how this CPS could be designed in a society that is not organized by commodities but by commons.

- 11.2 Thinking about the social impact of a CPS. Think about a smart watch that sets individual performance goals, measures heart beat, records how long the person stays active and sleeping, and also shows the most viewed news of the last hour. Discuss how this can be related to:

- data ownership;

- global platforms;

- fake news;

- hybrid war.

References

- 1 Cesarino L, Nardelli PHJ. The hidden hierarchy of far‐right digital guerrilla warfare. Digital War. 2021;2:16–20. https://doi.org/10.1057/s42984‐021‐00032‐3.

- 2 Marx K. Capital: A Critique of Political Economy. vol. 1. Progress Publishers. (Original work published 1867); 1887. Available at https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1867-c1/.

- 3 Rubin II. Essays on Marx's Theory of Value. vol. 23. Pattern Books; 2020.

- 4 Althusser L, Balibar E, Establet R, Ranciere J, Macherey P. Reading Capital: The Complete Edition. Verso; 2016.

- 5 Althusser L. On the Reproduction of Capitalism: Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses. Verso; 2014.

- 6 Merriam‐Webster Dictionary. Governance; 2021. Last accessed 29 September 2021. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/governance.

- 7 Facts NobelPrize org. Elinor Ostrom; 2021. Last accessed 29 September 2021. https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/economic-sciences/2009/ostrom/facts/.

- 8 Ostrom E. Governing the Commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action. Cambridge University Press; 1990.

- 9 Ostrom E, Janssen MA, Anderies JM. Going beyond panaceas. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104(39):15176–15178.

- 10 Ostrom E. A general framework for analyzing sustainability of social‐ecological systems. Science. 2009;325(5939):419–422.

- 11 Wolff RD, Resnick SA. Contending Economic Theories: Neoclassical, Keynesian, and Marxian. MIT Press; 2012.

- 12 Bak‐Coleman JB, Alfano M, Barfuss W, Bergstrom CT, Centeno MA, Couzin ID, et al. Stewardship of global collective behavior. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2021;118(27): e2025764118; https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2025764118.

- 13 Kühnlenz F, Nardelli PHJ, Karhinen S, Svento R. Implementing flexible demand: real‐time price vs. market integration. Energy. 2018;149:550–565.

- 14 Dawson A. People's Power: Reclaiming the Energy Commons. OR Books New York; 2020.

- 15 Palensky P, Dietrich D. Demand side management: demand response, intelligent energy systems, and smart loads. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics. 2011;7(3):381–388.

- 16 Arthur WB. Foundations of complexity economics. Nature Reviews Physics. 2021;3(2):136–145.

- 17 Blanchard BS, Fabrycky WJ. Systems Engineering and Analysis: Pearson New International Edition. Pearson Higher Ed; 2013.

- 18 Aglietta M. A Theory of Capitalist Regulation: The US Experience. vol. 28. Verso; 2000.

- 19 Bauwens M, Kostakis V, Pazaitis A. Peer to Peer: The Commons Manifesto. University of Westminster Press; 2019.

- 20 Feenberg A. Transforming Technology: A Critical Theory Revisited. Oxford University Press; 2002.

- 21 Nardelli PHJ, Alves H, Pinomaa A, Wahid S, Tomé MDC, Kosonen A, et al. Energy internet via packetized management: enabling technologies and deployment challenges. IEEE Access. 2019;7:16909–16924.

- 22 Giotitsas C, Nardelli PHJ, Kostakis V, Narayanan A. From private to public governance: the case for reconfiguring energy systems as a commons. Energy Research & Social Science. 2020;70:101737.

- 23 Nardelli PHJ, Hussain HM, Narayanan A, Yang Y. Virtual microgrid management via software‐defined energy network for electricity sharing: benefits and challenges. IEEE Systems, Man, and Cybernetics Magazine. 2021;7(3):10–19.

- 24 Giotitsas C, Nardelli PHJ, Williamson S, Roos A, Pournaras E, Kostakis V. Energy governance as a commons: engineering alternative socio‐technical configurations. Energy Research & Social Science. 2022;84: 102354. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S221462962100445X.

- 25 Hussain HM, Narayanan A, Nardelli PHJ, Yang Y. What is energy internet? Concepts, technologies, and future directions. IEEE Access. 2020;8:183127–183145.

- 26 Chan F, Wong T, Chan L. Flexible job‐shop scheduling problem under resource constraints. International Journal of Production Research. 2006;44(11):2071–2089.

- 27 Pournaras E. Collective learning: a 10‐year Odyssey to human‐centered distributed intelligence. In: 2020 IEEE International Conference on Autonomic Computing and Self‐Organizing Systems (ACSOS). IEEE; 2020. p. 205–214.

- 28 Mashlakov A, Pournaras E, Nardelli PHJ, Honkapuro S. Decentralized cooperative scheduling of prosumer flexibility under forecast uncertainties. Applied Energy. 2021;290:116706.

- 29 Voigt P, Von dem Bussche A. The EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). A Practical Guide, 1st Ed, Cham: Springer International Publishing. 2017;10:3152676.

- 30 Tikkinen‐Piri C, Rohunen A, Markkula J. EU general data protection regulation: changes and implications for personal data collecting companies. Computer Law & Security Review. 2018;34(1):134–153.

- 31 Ullah M, Nardelli PHJ, Wolff A, Smolander K. Twenty‐one key factors to choose an IoT platform: theoretical framework and its applications. IEEE Internet of Things Journal. 2020;7(10):10111–10119.

- 32 Ihlebæk KA, Sundet VS. Global platforms and asymmetrical power: industry dynamics and opportunities for policy change. New Media & Society. 2021;14614448211029662. https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448211029662

- 33 Wachter‐Boettcher S. Technically Wrong: Sexist Apps, Biased Algorithms, and Other Threats of Toxic Tech. W.W. Norton & Company; 2017.

- 34 Karppi T, Nieborg DB. Facebook confessions: corporate abdication and Silicon Valley dystopianism. New Media & Society. 2020;23(9):2634–2649. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444820933549.

- 35 Lazer DM, Baum MA, Benkler Y, Berinsky AJ, Greenhill KM, Menczer F, et al. The science of fake news. Science. 2018;359(6380):1094–1096.

- 36 Seger E, Avin S, Pearson G, Briers M, Ó Heigeartaigh S, Bacon H. Tackling Threats to Informed Decision‐Making in Democratic Societies: Promoting Epistemic Security in a Technologically‐Advanced World. The Alan Turing Institute; 2020.

- 37 Umpleby SA. A history of the cybernetics movement in the United States. Journal of the Washington Academy of Sciences. 2005;91(2): 54–66. https://www.jstor.org/stable/24531187.

- 38 Gerovitch S. From Newspeak to Cyberspeak: A History of Soviet Cybernetics. MIT Press; 2004.

- 39 Noble DF. Forces of Production: A Social History of Industrial Automation. Routledge; 2017.

- 40 Osinga FP. Science, Strategy and War: The Strategic Theory of John Boyd. Routledge; 2007.

- 41 Thomas T. Russia's reflexive control theory and the military. Journal of Slavic Military Studies. 2004;17(2):237–256.

- 42 Lefebvre V. Conflicting Structures. Leaf & Oaks Publishers; 2015.

- 43 Lepskiy V. Evolution of cybernetics: philosophical and methodological analysis. Kybernetes. 2018;47(2):249–261. https://doi.org/10.1108/K‐03‐2017‐0120.

- 44 Vasara A. Theory of Reflexive Control: Origins, Evolution and Application in the Framework of Contemporary Russian Military Strategy. National Defence University; 2020.

- 45 Reichborn‐Kjennerud E, Cullen P. What is hybrid warfare? NUPI Policy Brief; 2016.

- 46 Beer S, et al. Ten pints of Beer: the rationale of Stafford Beer's cybernetic books (1959–94). Kybernetes: The International Journal of Systems & Cybernetics 2000;29(5–6):558–572(15). https://doi.org/10.1108/03684920010333044.

- 47 Medina E. Cybernetic Revolutionaries: Technology and Politics in Allende's Chile. MIT Press; 2011.

- 48 Fisher M. Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative? John Hunt Publishing; 2009.