CHAPTER 7

Impact Investing

“The negative idea of Unselfishness carries with it the suggestion not primarily of securing good things for others, but of going without them ourselves, as if our abstinence and not their happiness was the important point. I do not think this is the Christian virtue of Love.”

—CS Lewis

A company is asking for an investment from you. Its numbers are incredible—the company projects 65% annualized returns over the next 10 years. What's more, you believe that it can accomplish this. In fact, this is, by your estimate, a conservative projection. One catch: the company employs slave labor in its manufacturing process (overseas, of course).

Clearly, no one would invest in this company (if you find yourself tempted, you should put this book down and read some books on moral philosophy or religion). There is, in fact, no financial return that could justify the enslavement of our fellow humans. Given a marketplace of investors who all turn down even such a lucrative offer, we could say that the cost of capital for this business is infinite. And that is part of the point of impact investing—to change the cost of capital for a business so that other businesses take note and change their behavior to reflect the norms and preferences of their investors. Given an infinite cost of capital, businesses will realize that slave labor is not a financially successful practice and abandon it.

We are all, therefore, impact investors, at least on some level.1 The conversation surrounding impact investing is not really about whether it should be done—the illustration above readily demonstrates that we all do it—rather, the conversation is about what matters to me. We can all agree that slavery is wrong. But what about fossil fuels? Or gender equality? Or investing in Japanese stocks?

It is here that the industry has taken its usual approach: we build products, then sell them to clients. Impact investing is no different: here is what we care about, so you should care about that, too. But goals‐based investing starts with the client's wishes. It is about the client's goals, not ours. I have found that, more than any other topic we may cover, impact, ethical, and environmental, social, and governance (ESG) investing is very personal. What you consider important may not be important to your client. What matters to me in impact/ESG investing is not necessarily what matters to you.

In that way, ethical/impact/ESG investing is a perfect topic for goals‐based portfolio theory. As should by now be obvious, investors very often have multiple goals they wish to achieve. As individuals have become more socially aware (and certainly more aware of the potential harms their investment dollars may enable), the goals‐space has now expanded to include objectives that are not strictly financial. Impact investing is one example of a nonfinancial, but very real, goal.

Yet these types of goals offer some specific challenges to the practitioner. First, since they are not financial nor futuristic, they are achievable right now. In other words, if your goal is to not invest in oil and gas companies, that goal can be accomplished by simply reallocating away from oil and gas companies. But what is the cost to your long‐term financial goals to avoid oil and gas companies in your portfolio? How much has your new probability of achievement changed by adding this restriction to your portfolio? Is that change worth it?

To date, these questions have been given only a superficial treatment. There are those who claim that ESG constraints and impact investing are a long‐term good for any portfolio—that it is just good investing. There are others who insist that investors must be giving up something to incorporate any investment constraint, ESG constraints included.

It is not my intent to wade into this debate. In my opinion, an honest review of the literature leaves me as undecided as I ever was. The point for goals‐based practitioners is not necessarily to have an answer or strong opinion on this topic. Rather, it is our job, as practitioners, to help investors accomplish their goals. If my client wishes to retire on a rowboat in the middle of Lake Erie, my job is to help her retire on a rowboat in the middle of Lake Erie, not to pass judgment on whether that is a worthy goal. Similarly, if it is our investor's objective to incorporate an ESG constraint or impact mandate, our role is to help her do so, and help her to manage any tradeoffs, not to impose our value judgements onto her decision. With the framework of goals‐based investing, we can now advise our clients whether or not they should incorporate an ESG or impact mandate, given their desire to achieve other goals, as well.

We begin, as usual, with an understanding of our client's goals, which includes understanding the time horizon, funding requirement, and total pool of current wealth. From there, we have the client rank her goals from most important to least important, then elicit the value ratios of each goal to the other (this is all covered in Chapter 3). Note that the impact mandate will simply be another goal in the goals‐space, listed and understood along with all the rest. The difference is that the impact mandate has no funding requirement, only an allocation requirement, so we have to code it a bit differently in the model.

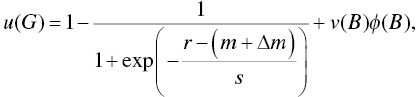

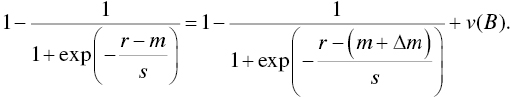

Pulling the goals‐based utility function, let us consider a two‐goal case for ease of discussion (so ![]() ):

):

where, as before, ![]() is the value of the client's most important goal, and

is the value of the client's most important goal, and ![]() is the value of the second‐most important goal. In this case, goal B is the impact investing mandate, and goal B is achieved if goal A's portfolio is invested according to the mandate, or not achieved otherwise. Leaning on the logistic distribution to assess probability (for tractability), we can model the two‐goal case with the mandate as

is the value of the second‐most important goal. In this case, goal B is the impact investing mandate, and goal B is achieved if goal A's portfolio is invested according to the mandate, or not achieved otherwise. Leaning on the logistic distribution to assess probability (for tractability), we can model the two‐goal case with the mandate as

where ![]() is the return drag of the impact mandate (if there is any),

is the return drag of the impact mandate (if there is any), ![]() is the annualized return required to achieve the goal,

is the annualized return required to achieve the goal, ![]() is the volatility of the portfolio, and

is the volatility of the portfolio, and ![]() is the expected return of the portfolio. Again,

is the expected return of the portfolio. Again, ![]() if the mandate (and return drag) are implemented, and

if the mandate (and return drag) are implemented, and ![]() otherwise.

otherwise.

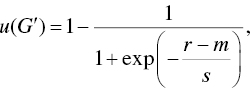

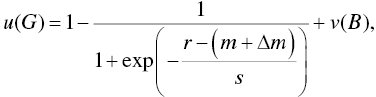

We can now model the investor's point of indifference—that is, when does the return drag of the impact mandate outweigh its added benefit? This indifference point will give us the maximum return drag our investor is willing to accept to implement the return mandate. Since the utility of the goals‐space without the mandate is (recall that ![]() , so it is not enumerated)

, so it is not enumerated)

and the utility of the goals‐space with the mandate is (recall that ![]() , so it is not enumerated)

, so it is not enumerated)

then the point of indifference is ![]() :

:

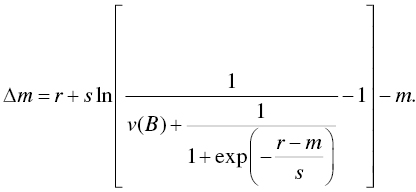

Solving for the maximum acceptable return drag, we have

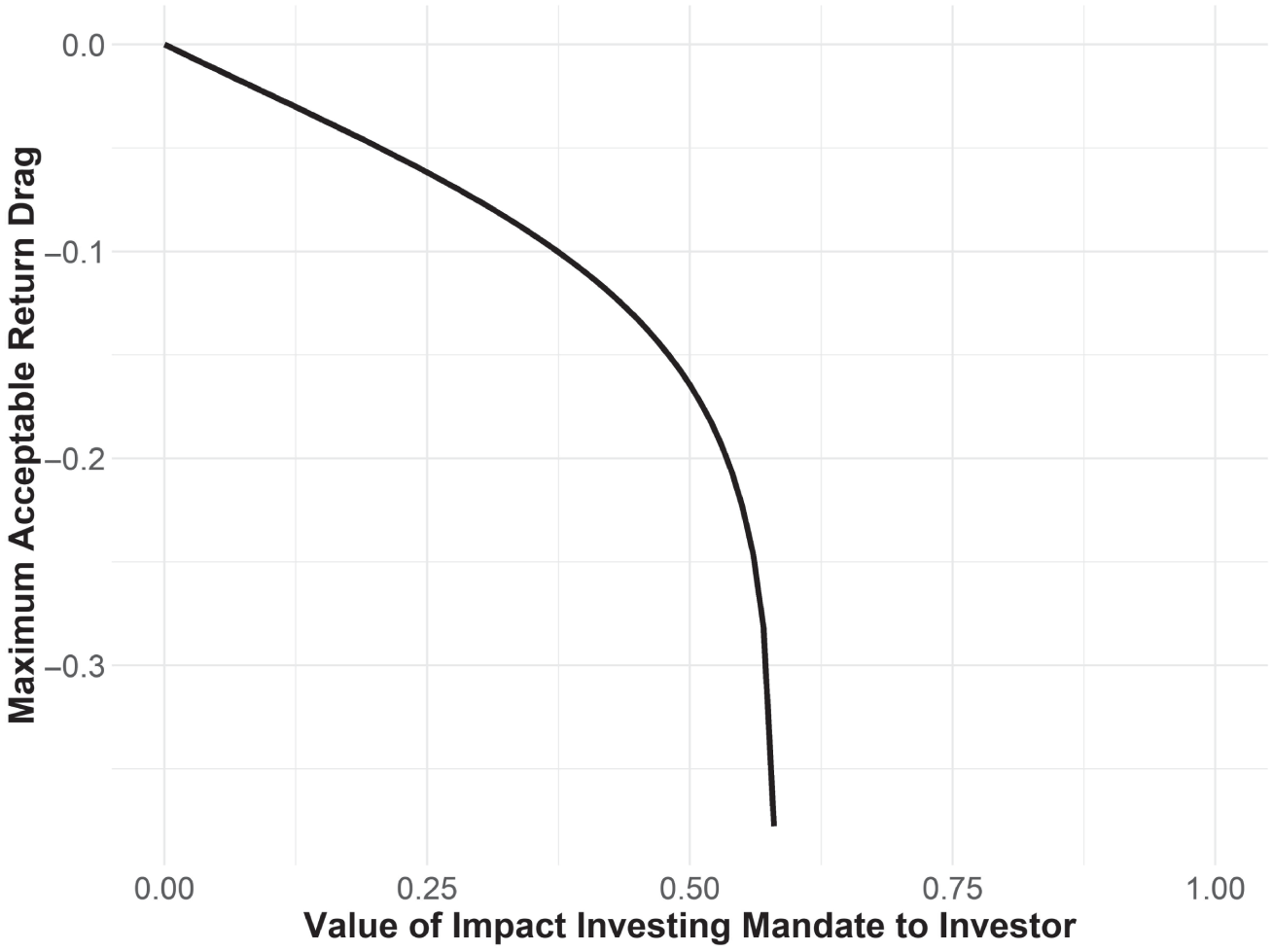

FIGURE 7.1 Maximum Acceptable Return Drag, as a Function of Mandate's Relative Value

Where required return is 6%, expected portfolio return is 8%, and expected portfolio volatility is 6%.

Clearly, the maximum return drag our client is willing to accept is a function of many things: how much return we expect to get from the unconstrained portfolio, how much volatility we can expect, the required return of the goal, and how much the impact mandate is valued relative to the other goal, ![]() . In Figure 7.1, everything is held constant except how much the investor values the impact mandate, which illustrates the asymptotic nature of the relationship. As the relative value of the mandate grows, our investor becomes willing to accept absurd levels of return drag.

. In Figure 7.1, everything is held constant except how much the investor values the impact mandate, which illustrates the asymptotic nature of the relationship. As the relative value of the mandate grows, our investor becomes willing to accept absurd levels of return drag.

Mathematically, this asymptote makes sense. Recalling our point of indifference equation from above, we can simplify it in an alternate way:

yields

where ![]() is the probability of achieving goal A without the impact mandate, and

is the probability of achieving goal A without the impact mandate, and ![]() is the probability of achieving goal A with the impact mandate. In English, this tells us that the value of the mandate is the amount of achievement probability our investor is willing to give up in her financial goal to pursue the impact mandate. Obviously, one can only give up the amount of achievement available in the first place—hence the asymptote. More importantly, this illuminates an important concept, which I dub the philanthropy limit.

is the probability of achieving goal A with the impact mandate. In English, this tells us that the value of the mandate is the amount of achievement probability our investor is willing to give up in her financial goal to pursue the impact mandate. Obviously, one can only give up the amount of achievement available in the first place—hence the asymptote. More importantly, this illuminates an important concept, which I dub the philanthropy limit.

As the impact mandate grows in importance to our investor, there is some point at which she ceases to be an investor and instead becomes a philanthropist. Philanthropists are content to lose 100% of their cash in pursuit of their goals, whereas investors expect some return on their cash. Admittedly, there is no exact point at which our impact investor becomes a philanthropist—it is much more a transition than a specific point, as our plot illustrates. Even so, it is important to help our clients understand the difference between investing and philanthropy! So, I like to label the philanthropy limit as the actual asymptotic limit. If you value the impact mandate more than that, you are very clearly a philanthropist, and your goal might be better achieved in that frame of mind.

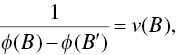

The philanthropy limit becomes clearer if we swap the ranking of goals. Rather than modeling the financial goal as the most important, we can label the impact goal as the most important (goal A) with the financial goal as the less important goal (goal B). Similar to before, we can determine the point at which our investor is indifferent to the achievement of the financial goal with the mandate and the achievement of the financial goal without the mandate. Let ![]() be the probability of achieving the financial goal without the mandate and let

be the probability of achieving the financial goal without the mandate and let ![]() be the probability of achieving the financial goal with the mandate. We can set up the problem as

be the probability of achieving the financial goal with the mandate. We can set up the problem as

When the impact mandate is in place, goal A is achieved, so ![]() , and we set

, and we set ![]() , per usual. Solving for the investor's value of goal B (which is the financial goal in this setup), we find

, per usual. Solving for the investor's value of goal B (which is the financial goal in this setup), we find

which is a contradiction! ![]() , meaning

, meaning ![]() , which directly contradicts our original definition, that the value of goal A is equal to 1 and that the value of goal B is less than the value of goal A:

, which directly contradicts our original definition, that the value of goal A is equal to 1 and that the value of goal B is less than the value of goal A: ![]() .

.

In other words, no investment solution exists if our investor values the impact mandate more highly than the financial goal. In that case, our investor is not an investor at all, but is instead a philanthropist. And this delineation is important because it can spark an important conversation. Namely, is an investment solution the best use of your capital, or would a direct gift to a philanthropic endeavor more readily accomplish your goal?

Of course, direct philanthropy and impact/ESG investing are not the same in practice. The idea behind impact/ESG investing is to decrease the costs of capital via financial markets for businesses with agreeable practices or products, thereby encouraging them to adjust. Direct philanthropy typically sidesteps financial markets altogether, so the net result is different in practice. Financially, however, it is the same to our client to invest in an unconstrained portfolio and then donate the annual return drag we would have been willing to accept to a philanthropic cause. That is, if you stood to gain 8% in the unconstrained portfolio and 5% in the impact portfolio, then receiving 8% return and donating three percentage points of your return every year to a relevant philanthropy is the same financially as investing in the impact portfolio (which returns 5%).

This framework also offers a method for allocating to philanthropic goals. By coding philanthropic concerns as another goal in the goals‐space, we can optimize our wealth across goals, and that optimization procedure will yield an amount dedicated to philanthropy—given all other goals and their inputs. Some decision with respect to a probability of achievement function would have to be made, but something simple could stand in for the general case (leaving specifics to the practitioner). A simple proportional funding function may do the trick: If the cause requires $1.00 to fund, and our investor funds $0.80, then the “probability of achievement” is $0.80/$1.00 = 80%.

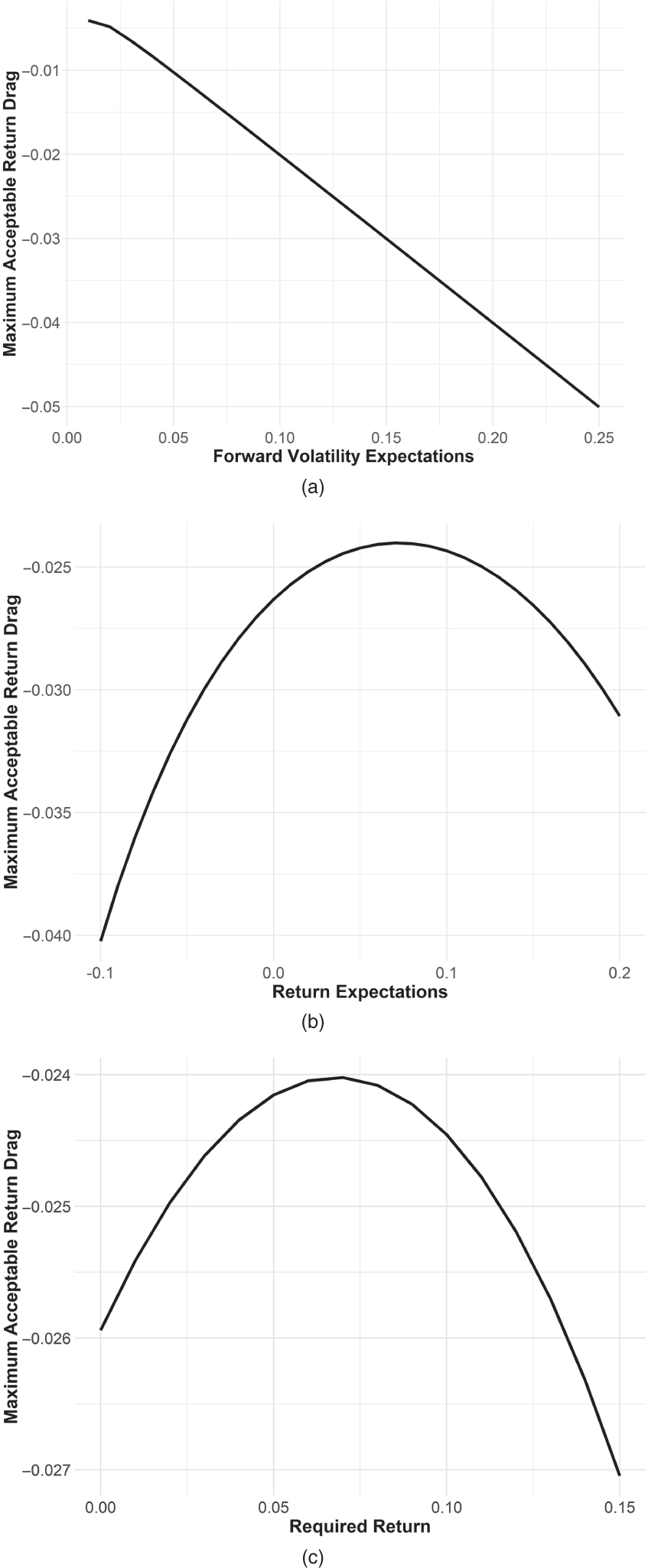

The goals‐based framework also reveals some important dynamics around willingness to pursue an impact mandate. It is not the same in all market environments. If we hold other factors constant and vary our portfolio return expectations, our volatility expectations, and our required return expectations, we find that each affects willingness differently.

Investors tend to be least willing to sacrifice return when portfolio volatility is smaller. As volatility expectations grow, so does an investor's willingness to sacrifice return, illustrated by Figure 7.2(a). This makes some intuitive sense: as volatility expectations grow, the probability of achieving the financial goal shrinks. This makes the utility offered by the secondary goal more important, and so return drag becomes more acceptable. Walking a client through her volatility expectations and asking her to imagine a higher or lower volatility environment may be useful in preparing her for her own shifting sentiment. With regard to accepting return drag, volatility expectations are the second most important factor, after the value of the mandate.

FIGURE 7.2 Other Factors Affecting Willingness to Accept Return Drag. Unless otherwise specified, in all figures required return equals 6%, expected return equals 8%, expected volatility equals 12%, and the value of the impact mandate is 0.05. (a) Expected volatility; (b) Expected returns; (c) Required return

As realized market returns shift the principal value of the portfolio, we can also expect investors to adjust their sentiment toward impact investing, but this shift is not a linear one. This market value adjustment shows up as a new required portfolio return (market gains yield lower future required returns; market losses yield higher future required returns). As Figure 7.2(c) shows, the relationship is an inverted parabola with investors being least willing near where the required return equals the expected portfolio return, and most willing as return requirements move away from this point in either direction. For example, if an investor expects a 6% portfolio return, she will be least willing to sacrifice return around the 6% required return mark, and more willing at the 3% or 9% required return mark. It is a similar case for shifting portfolio return expectations. As portfolio return expectations move away from equality with the required portfolio return, an investor becomes exponentially more willing to accept return drag (again, this is an inverted parabolic relationship, as Figure 7.2(b) shows).

It is not just market shifts that can move sentiment toward return drag. As we have discussed, the relative importance of the goal (impact mandate) is the most important factor. While individual investors may have a relatively constant valuation for this goal, this cannot be assumed for other account types, like trusts. It is not uncommon for a wealth‐creating generation to use trusts as a vehicle to pass along wealth to the next generation. For the bequeathing generation, it is likely that their estate goal is nearer the top of the Maslow‐Brunel pyramid (i.e. it is not a foundational goal, but more aspirational). The inheriting generation, however, is likely to view their inheritance nearer the bottom of the Maslow‐Brunel pyramid—it is likely a much more foundational goal. This means that each generation will value an impact mandate differently. In theory, the bequeathing generation should be more willing to accept a return drag to pursue an impact investing mandate, while the subsequent generation should be less willing.

Of course, up to now the drive to pursue impact and ESG mandates has tended to come from the younger generation. However, we should not assume that to always be true. For one, the luster of social consciousness can wear away with age or changing social norms. Also relevant: as the second generation learns, through experience, how fragile their corpus of wealth can be, willingness to sacrifice return for an impact mandate may be blunted. An assumption that return‐drag tolerance will be always constant is a dangerous one, not just for retaining clients, but also for the liability of trustees.

In any event, people tend to be less tolerant of return drag in their foundational goals than their aspirational ones. Circling back to the generational divide just mentioned, it may well be that younger investors are more willing to give up return for impact mandates, but whether they should be, given all of their other objectives, is a separate question. It may well be the practitioner's job to talk through a mismatch between what a client says and what a client should do. People are not always rational, after all.

Furthermore, balancing not just competing psychological interests but also the legal interests2 (in the case of trusts) of multiple generations is a delicate tightrope to walk. An understanding of the value placed on an impact mandate, not just today but also across various market environments and generations, is absolutely critical—and even then, ongoing adjustments seem likely. Building flexibility in the account and setting flexible expectations with the client are two key components to long‐term success in impact investing for goals‐based investors.

With impact investing, some of the benefits of goals‐based portfolio theory become clearer. Traditional portfolio theory has no guidance for the pursuit of nonfinancial objectives, whereas, as we have just discussed, goals‐based portfolio theory offers a rational framework for the management of any potential tradeoffs. It is the broader goals‐based approach, however, that lends the most value to clients, and ESG/impact investing is a great foil to see this. Currently, the industry imposes a particular view of ESG/impact investing on the client. That is, an asset manager will build a fund or a portfolio and then sell it to an investor, asking the investor to both buy in to the investment strategy as well as the fund manager's definition of ESG/impact. This is very clearly a top‐down philosophy.

But ESG and impact investing are very personal things, and not all investors define it the same way. I have a client, for example, whose father fought in the Pacific theater of World War II. She does not want to own any Japanese stocks. Of course, I have no problem owning Japanese stocks (assuming they are a worthwhile component of the portfolio). But this is her ethical constraint, and it is her money. My role is not to pass judgment on whether that is a worthy constraint, but rather to help her manage any potential tradeoffs that creates and invest the portfolio according to her wishes. In contrast to the current industry approach, this is decidedly a bottom‐up, client‐centered philosophy.

Every investor is different. Goals‐based theory accounts for those differences and offers a framework for managing them. Practitioners would do their clients good to adopt at least some of the methods.

Notes

- 1 Much of this discussion is taken from F. Parker, “Achieving Goals While Making an Impact: Balancing Financial Goals with Impact Investing,” Journal of Impact and ESG Investing 2, no. 3 (2021), DOI:

https://doi.org/10.3905/jseg.2021.1.014. - 2 A proper treatment of trust legalities is well beyond the scope of this book and my expertise. I would, however, highly recommend reading Schanzenbach and Sitkoff's paper, “Reconciling Fiduciary Duty and Social Conscience: The Law and Economics of ESG Investing by a Trustee,” Sanford Law Review 72 (2020): 381–454.