CHAPTER 14

The Future Structure of Wealth Management Firms

“Standing against the march of history might be a better solution, but only until history marches all over those who have resisted its progress.”

—Jean LP Brunel

Jean Brunel once quipped that goals‐based investing really does change everything.1 Now that we have covered the nuts‐and‐bolts of goals‐based portfolio theory, it should be clear how right he was! The whole approach of goals‐based investing changes both the structure and nature of client interactions, as well as the actual management of the investment portfolio. As should now be obvious, the math is fundamentally different for goals‐based investors. Another keen observation made by Brunel is that goals‐based investing blurs the line between financial planner and investment manager.2 Investment portfolios must be informed by goals, and goals, in turn, are influenced by the choice of investments.

Unfortunately, the current structure of wealth management firms is not conducive to delivering true goals‐based solutions. While financial planning has now long been part of most wealth management practices, to execute the plan, firms build model portfolios—large boxes that can only ever approximate client needs. Of course, to date this has been the only way to scale a practice. It is not possible to run thousands of different portfolios, each with a separate objective and investment universe without a considerable investment of man‐hours. Goals‐based portfolio theory brings a need for better plan implementation. Those differences between account objectives and the differences between clients, though ignored by monolithic model portfolios, are fundamental to the proper execution of a goals‐based plan.

Therefore, we need to update the structure and skill set of the wealth management firm.

To best understand the needed changes, we need to first understand the client experience. Goals‐based investing puts the client at the absolute center of everything we do, so to properly understand the changes needed it is best to first understand our center of gravity. Let's walk through the client experience from the point of first contact to the accomplishment of a goal.

A prospective client comes to the firm. Clients, of course, do not come to an advisor looking for goals; they have plenty of those. Clients come to the advisor looking for ways to accomplish their goals. The first meeting, in addition to the usual rapport‐building, should be focused on understanding the panoply of goals: their relative importance, time horizons, funding requirements, and all else that has been discussed in this book so far. A clear understanding of the client's current financial picture is also important. As a general rule, investment recommendations have no place being discussed in a first meeting. Certainly prospective clients will want some understanding of the firm's opinions of markets and investment solutions offering, and some brief discussion on the firm's points of difference is all sensible. But there is no way for an advisor to properly know what investment solutions are needed by the client without first doing the work of financial planning. Investments, in a goals‐based framework, are simply tools to get a job done. How can we reach for the correct tool when we do not yet know what job needs doing?

After the initial discussion, the advisor takes the client's data and builds a financial plan. Of course, the nature of the client and the listed goals will determine how detailed this financial plan needs to be (I am not fond of the 127‐page financial plan, simpler is better in my view). Much of the plan is calculating the relative value of goals, calculating the allocation of current wealth and future savings across goals, the determination of optimal investment allocations for each subaccount, the determination of taxes on the various account types, and so on. The role of the financial planner is to map the plan of attack—it is, perhaps, the most important role in the firm. Errors at this stage will compound into later stages, becoming magnified and possibly catastrophic to the client. Financial planning done well is of paramount importance.

Our prospective client is called back for a second meeting in which the financial plan is presented and discussed. Central focus should be on the achievement probabilities of goals, and discussion of the investment strategy and market philosophy is now warranted. A discussion of the biggest risks threatening the plan should also be discussed, and this is much more than investment risk. If the plan is fragile with respect to the client's human capital inputs, or to potential inheritance, these points need to be discussed. Risk allayment may be warranted, but only if it increases achievement probability, rather than decreasing it.

Assuming the client agrees to proceed, the plan is implemented by the investment strategy team.

Proper plan monitoring is important, too. Currently, most firms only report investment performance relative to some benchmark. But a benchmark is not our client's objective! Rather, we have some return that must be achieved to progress toward a goal. It would be considerably more sensible to report progress toward the goal, relative to what was originally forecast. Are we ahead of schedule or behind? If behind, why are we behind? Was this a forecasting error at the financial planning stage (i.e. we overestimated what was possible), was it a bad but transient market environment, or was it simply a poor job by the investment management team? Understanding what is wrong (and how to correct it) begins with proper, goals‐based, reporting, and goals‐based reporting is different from the current industry standard.

As mentioned, goals‐based reporting represents a move away from a focus on reporting performance relative to a benchmark and a move toward reporting performance relative to the client's goals. This is certainly more complicated, as it requires the reporting system to track the holdings and performance of each goal's subaccount, even if those subaccounts are aggregated in practice. It also requires a reporting system to track the projected funding of each goal for each client at any given time, perhaps with some margins of error, and that means synthesizing disparate pieces of information from the client's financial plan and the firm's investment view. How much liberty a firm should have in the presentation of such information is an open question, a question on which regulators will, no doubt, form an opinion.

None of this to say that reporting benchmarks carry no utility. Benchmarking is important as it easily shows the market opportunity of a given period. Given the client's personal restrictions, expecting something other than the opportunity set offered by the marketplace is unreasonable, and that should always be part of the conversation. Similarly, benchmarking can help asset managers identify sources of weakness. If progress toward a goal was hampered by a poor opportunity set (i.e. a bad market), some conversation around protecting hard‐won gains is reasonable, but perhaps not urgent. If, however, progress toward a goal was hampered by poor choices amidst a good opportunity set, the conversation (and solution) is much more pressing. In both cases, clients should be engaged in an honest discussion that is tailored to their level of sophistication—hence the need for more than simple performance‐relative‐to‐a‐benchmark reports.

Finally, if we have done our job correctly, our client attains her goal!

Now, I laughably oversimplified a step a few paragraphs ago. When I said, “The plan is implemented by the investment strategy team,” I skipped quite a lot. From the perspective of the client, other than the nature of the conversation and the nature of ongoing reports, there is little difference between the current service model and the goals‐based service model. Sorry to say that this is where the similarities end. Everything about the execution of a goals‐based approach is different. Pretty much everything behind the advisor‐client interaction has to change in the wealth management firm of the future.

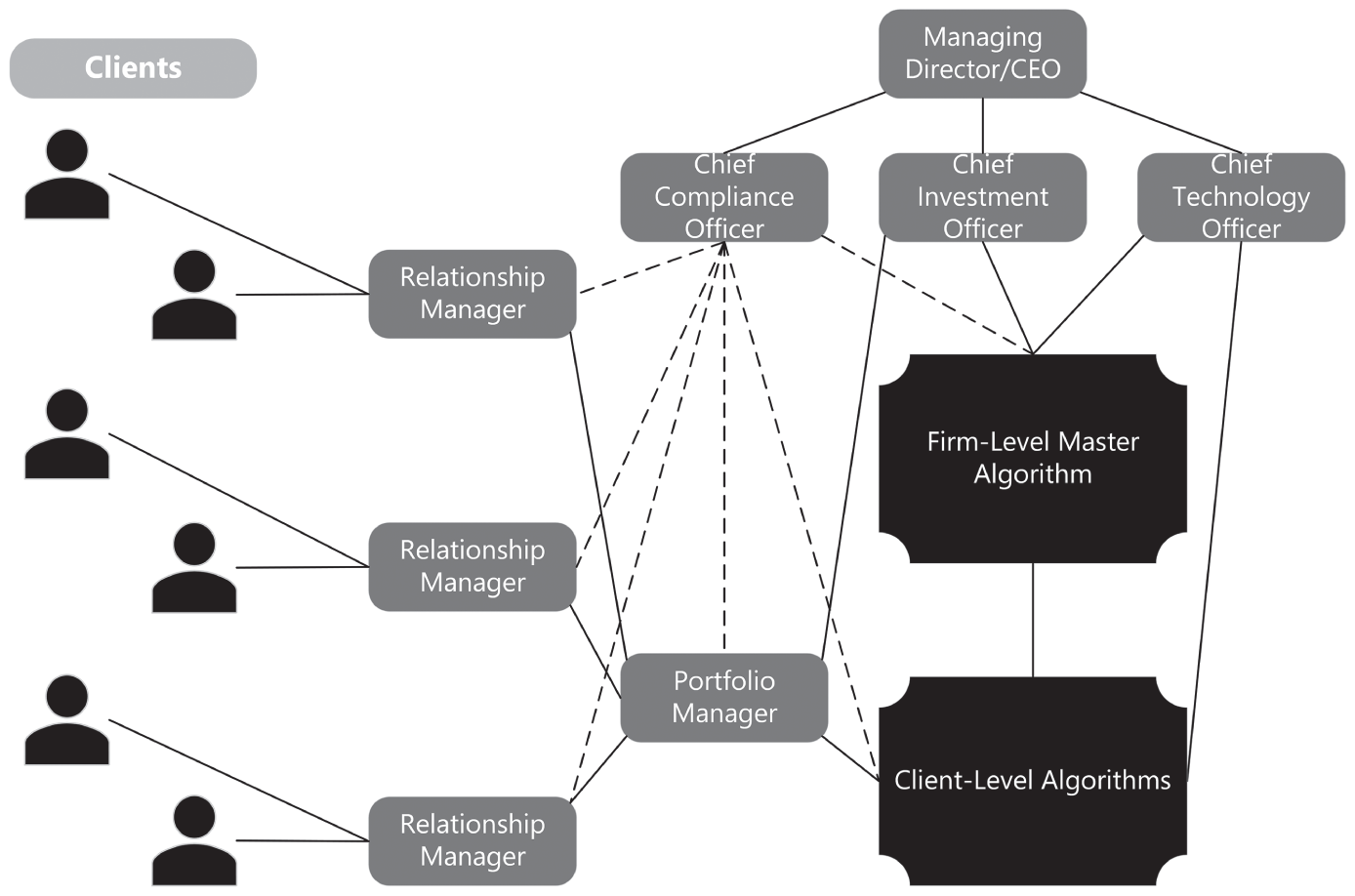

First, firms will need a two‐part technology solution to execute thousands of individual client plans at scale. Part A of the technology solution will be a firm‐level algorithm that houses the firm's view and philosophy of markets. If the firm, for example, believes value stocks and fundamental analysis are best for clients, the firm‐level algorithm will be responsible for intaking market data and building capital market expectations across the firm's investment universe. The automated component of this is important (though possibly not the only solution), because it is likely that each client—and possibly each client account—has a separate investment universe. Some accounts will benefit from dividend payments, while more tax sensitive accounts might avoid such forced taxable events, just to name one example. The point is, the firm's capital market expectations will need to be more granular than stocks, bonds, and commodities. Capital market expectations will need to include enough to enable the level of customization demanded by the goals‐based approach, likely a focus less on specific securities and more a focus on the rules that define the expectations of any security. The chief investment officer will be mainly responsible for overseeing the firm's master algorithm, though the role of “chief communicator” will maintain its importance.

ESG constraints are another aspect of the investment universe for which me must account. Every client has an individualized portfolio of ESG constraints. Up to now, the industry has focused on defining these constraints for clients, then “selling” investors on the value of that particular view. I see the future as clients defining it for themselves, and investment advisors implementing that customization. Ethical/ESG/impact mandates are as unique as the individuals who value them. What may be important to me may not be to a client, and vice versa.

This is one of the most exciting aspects of goals‐based investment tools, especially when implemented at the individual level rather than the model portfolio level. When we, as an industry, build and give individuals the tools to achieve both their financial goals and ethical goals through capital markets, then security prices will reflect not just all fundamental economic information about a company but all ethical information about a company as well. This could be capitalism's greatest moment. That will be when we can look at market prices and agree that they are an accurate mirror of who we are as a society. We may not like everything we see in the mirror, of course, but we could at least agree that it is an accurate reflection. But such a world only appears with individualized customization, and, likely more difficult, ecumenicity toward client ethical views that may challenge our own.

Such portfolio customization requires investment teams to maintain coverage on a wide range of securities. It seems unlikely to me that an investment team of reasonable size could maintain a database of all possible investment solutions by hand, and an investment universe that is too small would not deliver the level of customization that would be required across a whole book of accounts. Therefore, I see investment teams of the future focused on building the rules and technology systems that themselves build capital market expectations for thousands of possible investments, which is a significant shift in thinking.

Part B of this technology solution will be the account‐level algorithms. These algorithms will interface with the firm‐wide algo and implement each account's financial plan. They will, of course, take account of the tax consequences of trades, dividends, interest payments, along with the client's ethical constraints and financial goals. While at first they may not interface with markets directly, it is likely that they will come to fully trade accounts—minute by minute aligning the firm's market view and the client's financial plan with ongoing market developments.

Clearly, the maintenance of these systems will be the joint effort of investment and technology teams. Investment teams will be responsible for developing the firm's market philosophy and particular view, while the technology team will be responsible for designing and maintaining these systems. This means a team of coders, IT, and system architects—unfamiliar territory for investment advisors!

The role of the portfolio manager will evolve, as will the needed skill set. The PM role will become about translating the financial plan into code for the firm's systems to execute—overseeing the client‐level algorithms to which she is assigned. While I could see PMs themselves coding the algorithms using common components, more than likely the technology team will build modular systems with specialized graphical interfaces, allowing PMs to focus on constructing and translating the investment policy statement rather than on the nuts and bolts of the code. Keeping PMs away from the code base of the firm has the added advantages of reducing the risk of incorrect implementation as well as reducing the risk of fraud. However, such a system comes with the cost of added development time and increased monetary costs.

The role of the compliance team will have to shift, as well. With tens of thousands of lines of code running considerable sums of money, compliance teams will need to ensure that the architects of these systems (the technology and investment teams) are not burying millisecond frauds amongst legitimate code. It will also fall to compliance teams to answer regulators' questions. No doubt that will be a significant undertaking—especially as this structure will be just as new to regulators as it is to practitioners. All of this in addition to the already traditional role compliance teams play in overseeing advisors.

Regulators will need to adapt, as well. The expectation that every trade can be reviewed and explained may be too much. The focus will need to shift toward actual client experience with the firm's technology (i.e. is it doing what we said it would do?). There is also the move away from risk‐tolerance questionnaires (which are entirely superfluous in the goals‐based framework), and the needs of ![]() portfolios. Exactly how regulators will feel about those dramatic shifts remains to be seen. Likely the first focus for regulators will be ensuring there are no frauds built into the firm's code base. Two to three lines of code are all it would take to create a front‐running scheme in an inattentive firm's algorithms. Finding malicious code amongst tens of thousands of lines is a problem yet to be solved.

portfolios. Exactly how regulators will feel about those dramatic shifts remains to be seen. Likely the first focus for regulators will be ensuring there are no frauds built into the firm's code base. Two to three lines of code are all it would take to create a front‐running scheme in an inattentive firm's algorithms. Finding malicious code amongst tens of thousands of lines is a problem yet to be solved.

Finally, a technology team will need to keep this whole system friction‐free. At the scale of a firm, the ongoing and growing computing needs—in addition to the traditional IT service—will need to grow and develop. Not to mention, a firm will need to keep pace with the ongoing shifts in enterprise‐level technology architecture. It also seems likely that the technology team will aid the compliance team in finding and protecting the code base from fraud. Much research in this field is needed (does this field even exist yet?). Indeed, it is my strong belief that we are entering an age when Nobel laureates in economics will be computer scientists by trade.

FIGURE 14.1 Possible Future Org Chart

Behind the client‐advisor interaction the wealth management firm of the future will need to look more like a technology firm than a traditional wealth management shop, as Figure 14.1 demonstrates. The transition to this adjusted set up is likely to take decades, but Luddite firms are sure to be left behind. Not only will clients come to expect a fully customized solution, but it is also how firms will stave‐off the “feepocalypse” that has long been foretold. I believe that people will pay for legitimately better solutions. In the end, the theory, execution, skill sets, and firm structure should all coalesce around one objective: delivering the best solution to the client. With a dogged focus on that, firms will do no less than thrive.

Of course, many firms will be loath to implement such changes. The cost alone could be considerable. Technologists do not come cheap and the prospect of retooling the skill set of an entire firm is daunting, to be sure. But there is a middle ground that could help to ease the transition. Firms that wish to continue managing model portfolios while incorporating some goals‐based techniques could do so with reasonable ease. We know that two of the biggest influences on goals‐based portfolios are required returns, which affects portfolio allocation, and time horizon, which affects risk control. These two can be combined into model portfolios that look like Table 14.1. By managing the models to these two variables firms can rightfully claim they are incorporating goals‐based concerns, and clients can rest assured that their portfolio is, at a minimum, managed with allocations and risk controls that maximize the probability of achieving their financial goals.

TABLE 14.1 Example Goals‐Based Model Portfolio Structure

| REQUIRED RETURN | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4% | 6% | 9% | ||

| YEARS TO GOAL | 5 | 4%, 5 Year | 6%, 5 Year | 9%, 5 Year |

| 10 | 4%, 10 Year | 6%, 10 Year | 9%, 10 Year | |

| 15+ | 4%, 15+ Year | 6%, 15+ Year | 9%, 15+ Year | |

In this approach, the firm builds capital market expectations and, rather than infuse individual client portfolios with those expectations, the firm simply optimizes asset allocations based on a representative goal. The 6%, 10‐year portfolio, for example, would be optimized to deliver a 6% annualized return over a period of 10 years. The practitioner would need to update the client's model assignment each year to ensure the goal the allocation remains appropriate—what begins as a 10‐year goal becomes a 7‐year goal after 3 years have passed. The other advantage to this approach is that the portfolios could be blended to solve for those years that are not represented (the 6%, 10‐year portfolio could be blended with the 6%, 5‐year portfolio to yield a 6%, 7‐year portfolio, for example).3

Clearly, this comes with a considerable loss of customization, both with regards to impact/ESG concerns as well as with regard to taxes. A “representative client” would have to serve to estimate tax impacts of portfolio decisions, which is certainly not ideal. This also leaves open the question of whether highly appreciated transferred‐in positions should be sold or blended. Even with these questions, clients would still be better served by this middle ground than by the existing low‐variance to high‐variance model structure that carries no goals‐based concerns whatsoever.

Why not simply use a glide‐path fund? The central reason is that they are not allocated with any regard whatsoever to a required return. Rather than assume some goal needs to be accomplished, they simply grow more conservative in the allocation over time—whether that is in the best interest of the client's goal or not. That is, to me, like buying a smaller horse as you get older so that it doesn't hurt as much when it kicks. While that may be safer day‐to‐day, a smaller horse also does considerably less work. For investors who need to accomplish goals, a portfolio that delivers less and less return as time passes is likely to make it harder to achieve goals, not easier.4 Glide‐path portfolios are built on a psychological sense of safety, rather than a rational sense of goal achievement. To my mind, then, they have no real place in a goals‐based portfolio.

Most firms will need to change something about their current approach. Technology, skill sets, organizational charts, asset allocation engines, even marketing should shift to align with a goals‐based methodology. In my view, firms that fail to make this transition will be swept away by those who do. Clients intuitively understand when an approach is better for them, even if they may not understand all the technicalities of why. Even absent full customization, there are some basic changes to the model portfolio structure that would better serve clients. It is my genuine belief that people will pay for real value. Goals‐based investing is about delivering real value to real people in the real world. For their own sake, firms would do well to get on board sooner rather than later!

Those that do not are very likely to be left behind.

Notes

- 1 J. Brunel, Goals‐Based Wealth Management (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2015).

- 2 J. Brunel, “Extending the Goals‐Based Framework to Comprise Both Investment and Financial Planning,” Journal of Wealth Management, 24, no. 4 (2020): 1–16. DOI:

https://doi.org/10.3905/jwm.2019.1.096. - 3 Blending goals‐based portfolios like this brings up a whole separate theoretical issue, one that I do not wish to tackle here. In short, the portfolios can be blended horizontally or vertically, but not diagonally, though the validity of this will vary greatly with the firm's view of markets and methods for risk control. Firms interested in the approach can experiment themselves and find the best way to blend goals‐based model portfolios.

- 4 This intuition was backed up by a rigorous quantitative analysis, showing that as investors withdraw funds through retirement, they may need to grow more aggressive in their portfolio allocations rather than less. See S. R. Das, D. Ostrov, A. Casanova, A. Radhakrishnan, and D. Srivastav, “Combining Investment and Tax Strategies for Optimizing Lifetime Solvency under Uncertain Returns and Mortality,” Journal of Risk and Financial Management 14, no. 285 (2021): 1–25. DOI:

https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm14070285.