Chapter 9

![]()

Problem-Solving Principles: Strive Toward a Clear Direction Through Experimenting

One area where I think we are especially distinctive is failure. I believe we are the best place in the world to fail (we have plenty of practice!), and failure and invention are inseparable twins. To invent you have to experiment, and if you know in advance that it’s going to work, it’s not an experiment.

—Jeff Bezos, Amazon founder

PROBLEM SOLVING AS SCIENCE

Toyota Business Practices (Chapter 2) is Toyota’s problem-solving method. When someone says “I am a problem solver,” they often mean they are fire fighters—fixing things that are broken. This is not what we mean by problem solving. There are several common understandings in Toyota about problem solving. First, there is no problem without a standard. A standard can be a policy, an engineering specification, or an aspirational target, and it can come from inside or outside the organization. The current state is then compared with the standard, and the gap is a problem. The focus of problem solving is striving to close the gap between the actual condition and the standard. It goes far beyond fixing things that are broken.

Second, a problem is not an opportunity. It is a “problem” because there is a gap that needs to be closed. Closing the gap is not some nice opportunity in Toyota. It is an obligation.

Third, problem solving should be a focused search in the direction of the target. Those who have been students of a Toyota master trainer quickly tire of the incessant questions: “What is the purpose?” and “Why focus on this instead of that?” “There is waste, and we want to eliminate it” is never a sufficient reason. There must be a defined need, ultimately defined as a measurable or observable target.

But Toyota Business Practices is more than a problem-solving method. It is an approach to developing people to think deeply about their goals and how to achieve them. It is a teaching method to develop a way of thinking, a pattern. The way of thinking is drilled into the student until it is a habit that will automatically be drawn on to address any problem, big or small.

If we follow a standard method that becomes a habit, we do not have to think deeply, which conserves energy. When we strive toward an ambitious goal, we will need to discover new information and innovate, which heavily taxes our prefrontal cortex. But if we draw on an established routine for approaching the improvement, one that we have practiced many times, we will have less of a burden on our brain. We still have to navigate through uncertain territory, but we will not have to, in parallel, teach ourselves an approach to navigating.

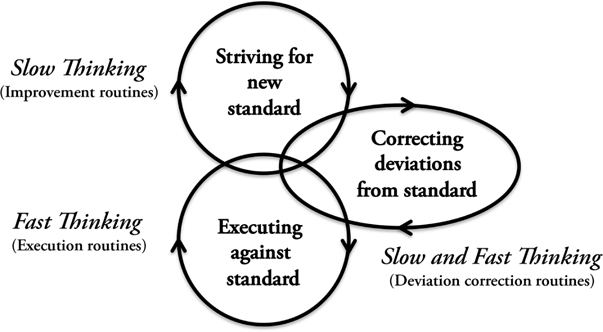

Our lives at work and at home are full of routines (see Figure 9.1). When we are performing tasks using a standard method that we have practiced, we are using an execution routine—getting dressed, driving a car, balancing our checkbook, checking our e-mail, and the list goes on. Daniel Kahneman, the Nobel prize winner, called this fast thinking. It is as if we are on automatic pilot. Ever had the experience of arriving at work and you can’t remember anything about the drive there? You are doing fast thinking, almost in the background, to drive this well-practiced route. Your brain loves it—it conserves mental energy to be saved for your survival.

Figure 9.1 Standards and problem-solving routines

See Daniel Kahneman, Thinking, Fast and Slow, 2011.

The mental work of striving for a new standard requires a lot of activity in the prefrontal cortex—what Daniel Kahneman calls “slow thinking,” deep and intensive. As we have repeatedly emphasized, slow thinking is painful and requires a lot of mental energy, and therefore we tend to avoid it if possible. Kahneman calls this “the law of least mental effort.” Unfortunately, as a result, we attempt to use fast thinking even when slow thinking is called for. That is why we must work so hard to develop the habits of scientific thinking.

Correcting deviations to an already standard method that we have practiced is somewhere in between. Again we will draw on our habits. For example, one manager may think there is an easy solution to every case of a slippage in production or quality or safety and run in to implement the known solution. On the other hand, a manager who has learned a more deliberate improvement process will see this as yet another gap between the standard and actual, and his improvement routine will kick into gear. Therefore, we are always using routines either to conduct work that we are familiar with or to face a challenging goal that requires innovative thinking. Tough problems will require routines for “slow thinking,” deep and intensive, while simple problems that we already know how to solve can draw on existing routines or “fast thinking.”1

We caution that correcting deviations from the standard is very different from striving for a new level of performance. One of the greatest systems thinkers, Russell Ackoff, made this distinction very clear:2

A defect is something that is wrong . . . When you get rid of something that you don’t want you do not necessarily get what you do want. So finding deficiencies and getting rid of them is not a way of improving performance of the system.

What Is Scientific Thinking?

I always had a bit of slow thinking in me, which is why I pursued a PhD and wanted to be a professor. Getting a PhD in sociology at the University of Massachusetts in the late 1970s put me at the center of debates about the nature of social science, a decidedly slow thinking process. Sociology, the study of people in groups and social systems, is perhaps the most complex science, with many variables interacting in complex ways. My PhD advisor, Peter Rossi, was known as one of the leaders in quantitative sociology. His focus was applied sociology to inform policy. Like the Toyota folks, he valued managing by facts, which to him was mainly large data sets. He believed the ultimate test of the efficacy of a policy was a large social experiment comparing a treatment group with a control group, such as experimenting with different forms of unemployment insurance.

A number of other sociology faculty were violently opposed to Rossi’s approach. They believed there were severe limits in our ability to understand social phenomena through the lens of statistical analysis. There were various tribes that did qualitative social research—observing and meticulously recording notes and seeking to build theory from the ground up. Ohno’s admonition to stand in one place and observe without preconceptions would resonate with these faculty members. As you might imagine from this book I have increasingly grown to appreciate the qualitative researchers and wish I had spent more time learning from them when I was in graduate school.

A Practical View of Scientific Thinking

Karyn sent me an eye-opening article by Robin Wall Kimmerer about the nature of science. Kimmerer is a Native American woman whose PhD dissertation was on moss, and her first book was called Gathering Moss.3 Compared with sociology, what could be a simpler application of the traditional scientific method than to study moss? It turns out there is much more to the study of plant life than I ever imagined.

Kimmerer’s father was forced off an Indian reservation in New York State and sent to a school designed to assimilate Native American children. Over time her family bucked this trend and worked hard to rekindle tribal connections, which included getting close to nature. Robin Wall Kimmerer was well educated in traditional American schools and earned her PhD in botany. She describes her learning journey as a circle. She loved plants as a child, observing them with awe and living among them, then conformed to the traditional scientific view of studying plant life from a distance, and then returned to learning through the senses in a spiritual connection with nature. She now spends much of her time living among plant life and observing it with childlike awe.

Kimmerer writes about “two ways of knowing.”4 One is the traditional scientific method of isolating samples in a lab, studying the world as an object, and attempting to make generalizations. The other is an observational approach, like that used by qualitative social researchers, based on interacting with, and sharing learning with, the life-form being studied. She explains this in a deep and personal way:

Western science explicitly separates observer and observed. It’s rule number one: keep yourself out of the experiment. . . . In the traditional way of learning, instead of conducting a tightly controlled experiment, you interact with the being in question—with that plant, with that stream. And you watch what happens to everything around it too. The idea is to pay attention to the living world as if it were a spider’s web: when you touch one part, the whole web responds. Experimental hypothesis-driven science looks just at that one point you touched.

Her patient, direct observation of nature has led to many surprising findings, such as “Plants certainly do communicate, primarily through exchange of chemical signals. They inform one another of insect and pathogen attacks for example, which allows them to mount defenses.”

Detailed observations of nature also have practical value for the very preservation of life. For example, salmon fishermen will not survive very long if they do not learn about the mating and migration habits of salmon and about specific environmental conditions, such as the presence of mosquitos and how they will affect the stock of salmon and where they will be at a particular time.

We can see parallels between the way Kimmerer came to learn about plant life and the way Pierre Nadeau learned sword making. Kimmerer’s teachers were the plant life. Pierre learned from a master sword maker, but actually his most important lessons were learned by his body, in the process of working with metal.

Both Kimmerer and Nadeau were learning a science, but it was a practical view of science. Their goal was to deeply learn and understand, not to poke and prod and divide and compartmentalize the subject in order to test generalizations.

Lean Management and Scientific Thinking

At the heart of lean management is scientific thinking. It was not a casual decision for James Womack and Daniel Jones to call their seminal book Lean Thinking.5 They could have called it Lean Processes, or Lean Implementation, or Lean Deployment, but they called it Lean Thinking. In the book they tell a story of a Japanese sensei practically being begged and cajoled into coming to America to teach about the Toyota Production System. He was invited to advise a division of Danaher Corporation that made brakes. The sensei at first refused to come, then came to the plant and immediately went back to Japan. He said the Americans were “concrete heads” and would never understand.

After further cajoling by the president, who flew to Japan, he agreed to come back to America and warned that if anyone questioned anything he said or did not comply, he would be on the next plane to Japan. The people at Danaher did everything he asked, and he continued to teach them. He was brutal, for example, using a chainsaw to cut down shelves of inventory and then asking his students to place all the inventory on the floor and spend day and night over the weekend figuring out what to get rid of and how to organize the rest so they could continue manufacturing on Monday. Danaher calls these dramatic displays “kaizen theater,” and the company still practices this internally. The point of the theater is to open people up to a new way of thinking, instead of accepting things as they are.

Danaher’s business model is to buy underperforming companies and use the Danaher Business System to raise their performance level and profitability. It works. Danaher is very profitable and keeps growing year after year. For example, in 1994 its total sales were $1.29 billion, and by 2014 they reached $19.9 billion. What Danaher’s leaders learned was a new way of thinking, and they have used it repeatedly to elevate the performance of companies they purchase.

Taichi Ohno provides some perspective on the deep thinking at the core of the Toyota Way: “The Toyota style is not to create results by working hard. It is a system that says there is no limit to people’s creativity. People don’t go to Toyota to ‘work’; they go there to ‘think.’”

From the early days the Toyota Production System was equated with the scientific method. One of Taichi Ohno’s star students, Hajime Ohba, explained it this way: “TPS is built on the scientific way of thinking. How do I respond to this problem? It is not a toolbox. You must be willing to start small, and learn through trial and error.”

If you watch Ohba work, you will see that a project with a new client who desires to learn TPS always starts with a big challenge, but then the work itself focuses on a very small area. A client who wants to start by implementing a future-state value-stream map will be asked instead to start work in one area without spending money. “Let’s start small, and learn through trial and error.” The reason is that the learner cannot accurately guess at all the problems and appropriate countermeasures entailed in a major transformation of all the things shown on the future-state value-stream map. The client company must discover the value of learning by trial and error and learn that it knows much less than it thinks it knows.

Ohba is like Nadeau’s sword master teacher who refused to answer questions if he thought it would encourage the student to think he knew before he actually learned through the body. Ohba refused to show his students in companies the value-stream maps because it would confuse them—“they will not understand.” But even worse, they might think they understand.

View of Scientific Thinking Underlying Kata

If lean is based on scientific thinking, and our brains punish us for trying to think slowly and deeply, what are we to do? The answer is practice. Mike Rother describes the improvement kata as “a process of deliberate practice to develop more scientific thinking in groups of people who work together.”6 He is not interested in turning people into scientists for the purpose of developing universal theories. His goal is to develop practical scientific thinking to improve toward a clear vision of what we need to achieve to be successful. Practical scientific thinking is a life skill.

The improvement kata pattern is designed to address common weaknesses in how adults respond to problems. This includes observing only superficially and filling in blanks in our understanding by making assumptions without even realizing it. It includes jumping into a waste-elimination mode before clearly understanding our direction. And it includes implementing “solutions” without taking the time to predict what will happen so we can compare the prediction with what actually happens and reflect on what we learned.

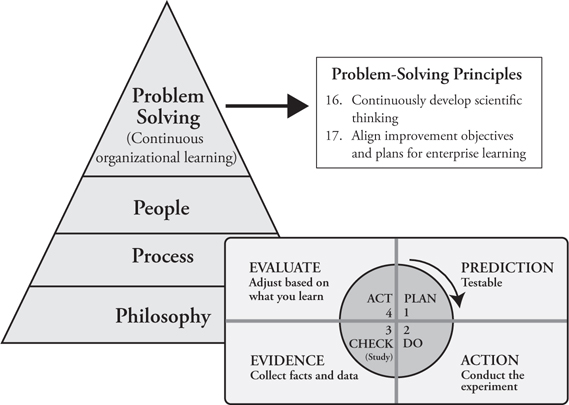

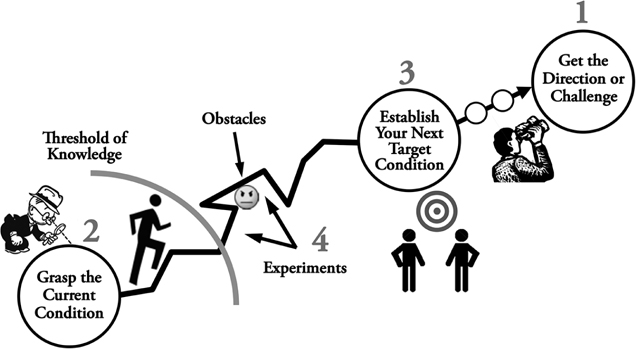

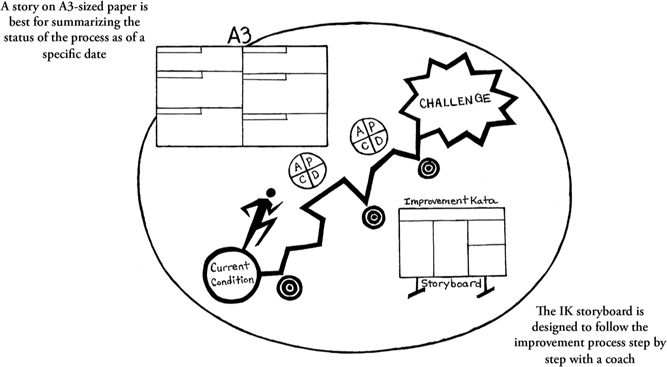

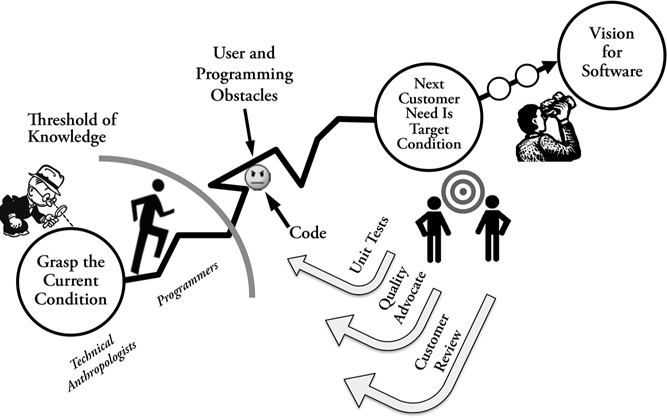

Earlier in the book, we introduced the 4P model and called the fourth P problem solving. We do not mean fighting fires or reacting to all the problems we notice. For us problem solving is a deliberate process of learning our way to achieving a clearly defined vision (see Figure 9.2). Ultimately it is a process of continuous learning at the individual level, group level, and organizational level.

Figure 9.2 Problem-solving principles

We borrowed from Rother in mapping PDCA to the common process of scientific experimentation. In the final analysis the Plan leads to a prediction, or hypothesis. The hypothesis is the countermeasure that we expect will move us in the direction of the challenge. It is a hypothesis because we do not assume we know it will work. At this point it is a theory to be tested. The Do means we run the experiment. Let’s try it and see what we can learn. As Jeff Bezos notes, it is not an experiment if you know what is going to happen. If you actually know then just do it. The Check (or Study, if the process is PDSA) is when we collect the data and facts to assess what happened. Finally we move to the Act stage, where we evaluate what we learned, which prepares us to plan our next experiment, and the cycle continues.

The starting point is to “continuously develop scientific thinking” of the practical variety. We will consider Toyota’s approach to developing scientific thinking and relate this to the improvement kata and coaching kata. As the skills and mindset of scientific thinking mature, the organization is better able to “align improvement objectives and plans for enterprise learning.”

PRINCIPLE 16: CONTINUOUSLY DEVELOP SCIENTIFIC THINKING

Managing to Learn Through True A3 Coaching

John Shook was the first foreign national to become a manager for Toyota Motor Company in Japan. He wrote and spoke Japanese and was hired in 1983 as Toyota was preparing to launch NUMMI. At the time TPS was not well documented, and John had to piece together the knowledge to develop training materials to teach the Americans hired for NUMMI. In this unique position John was taught and coached by many of the best in Toyota. He was exposed firsthand to Toyota’s unique culture, including the role of A3 reports, a report on one side of an A3-size paper. His first boss emphasized that he needed to learn how to “use the organization” to get anything important accomplished. A3 was one tool to help in using the organization.

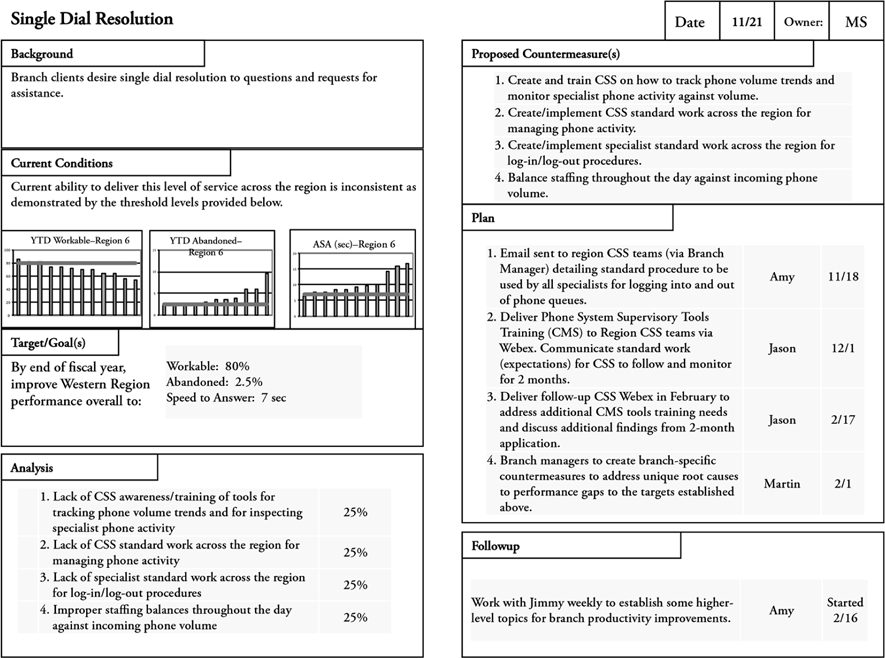

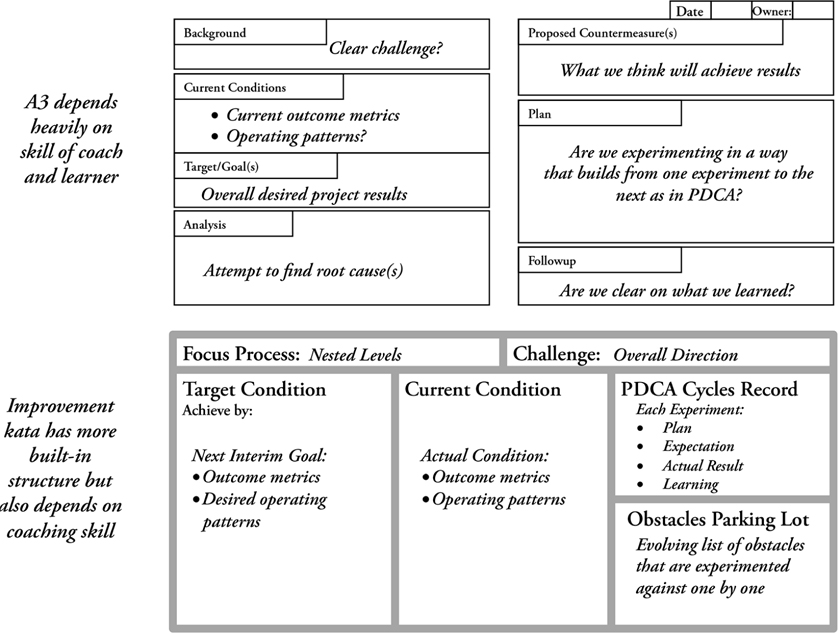

There are a variety of types of A3 reports ranging from the highly structured problem-solving story to the very unspecified format for an information story.7 An example format of a problem-solving A3 is shown in Figure 9.3. This is one I got from Toyota. It is curious that after the Do box there is one box which would include the Check and the Act which leaves little room for documenting results. We are presenting this as a common A3 problem solving format, but there are many variations.

Figure 9.3 Problem-solving A3

A lot of information can be jammed into a well-constructed A3. In fact, the project plan for NUMMI was on an A3 signed off by vice presidents and cascaded down to department managers who then had to develop their own A3s on how they would support the plan. At each step there was a deliberate and exhaustive process of discussion, debate, and revision after revision. One person was responsible for each A3, including gathering and using input from appropriate people. Nemawashi is the process of seeking information and ideas from many people, often one by one, and the “A3 story” evolves through investigation and synthesis. The A3 is a living document to be used in dialogue with others. Its power is in quick communication with others.

The final A3 is a snapshot of the overall process of planning or solving a problem, but it does not give any insight into the learning process that produced it. To better understand the full story, one would have to view the multiple iterations that got torn up, torn down, and revised and follow the evolution of the writer’s thinking, discussions, and experimentation.

The A3 report came to be a hot tool used by lean practitioners outside of Toyota. After all, Toyota was the benchmark and used A3, so lean companies should use A3. When John saw how it was being used by “outsiders,” he shuddered. He had gone through many years of training and practice on how to define a problem, how to deeply observe the actual process, how to ask questions, and how to conduct nemawashi, while constantly responding to questions and challenges from his various coaches. It was always intense and exhausting—lots of slow thinking. The A3 can be a powerful tool to summarize thinking at the moment and to continue to work through the organization—when this tool is used within the context of coaching by an experienced mentor. But writing an A3 does not somehow transform the writer into an excellent thinker or leader (see Figure 9.4) any more than handing someone a laptop would make him or her a great author.

Figure 9.4 Learning A3 thinking requires a seasoned coach; the A3 tool format is not enough

Source: Mike Rother

John Shook wrote Managing to Learn8 with the intention of correcting many misconceptions about the role of the A3. As John writes in the book:

I discovered the A3 process of managing to learn firsthand during the natural course of my work in Toyota City. . . . My colleagues and I wrote A3s almost daily. We would joke, and lament, that it seemed we would regularly rewrite A3s 10 times or more. We would write and revise them, tear them up and start over, discuss them and curse them, all as ways of clarifying our own thinking, learning from others, informing and teaching others, capturing lessons learned, hammering down decisions, and reflecting on what was going on.

Managing to Learn tells the story of a young manager, Desi Porter, who is assigned to improve Japanese documentation for a major plant expansion. The last time this was done, there were many problems in the translation causing significant project delays. He is asked by his boss to develop an A3 for the preliminary plan to address the documentation issue. He did have some experience writing simple problem-solving A3s, but this was a much more complex assignment.

Buckling down he launched into developing an A3 that would get quick approval and impress the boss. This would allow him to then dive into implementation. Desi Porter used the scant information that he already knew to “write the report.” This began an odyssey that Porter could not have imagined, as his boss, Ken Sanderson, incessantly questioned everything, driving Porter to the gemba to learn and challenge his thinking about even the smallest detail of the project. He was being mentored in A3 thinking to learn how to “use the organization,” not simply write a report.

The learning process began when Desi proudly presented what he thought was his completed A3 to Ken Sanderson. Ken focused in on the goals and targets that were to simplify and standardize the process and reduce costs by 10 percent. Ken wondered why Desi assumed he had to standardize the process. Was that really a main goal or an assumed countermeasure? And how did Desi decide the main goal was cost reduction and come up with a 10 percent target? It seemed that quality of the translation work was the priority.

Desi Porter was flabbergasted by Ken’s questions. Of course, he believed he understood the problem and had good ideas on how to solve it. He had learned from his research that in the last project the company had used multiple vendors with varying cost and performance, so it stands to reason this needed to be fixed with a more rigorous selection process. Ken replied rather harshly to Desi’s defensive responses:

That is all very general and vague. Do you know how the process actually works? Can you tell me what is causing the problems and delays? What is actually causing the cost overruns?

This intensive questioning led Desi Porter to more carefully study the process at the gemba where he discovered most of his preconceptions were wrong. This led to rethinking and rewriting and more and more questioning from Ken. It was not simply an issue of vendor selection for cost reduction. Many of the translation problems originated in the IT system. The bigger issue was the quality of the translation, as the cost of delays was many times more than any savings that might come from a cheaper translating service. The final A3 bears little resemblance to the original. In the process of digging deeper and deeper and being forced to think and rethink, Desi Porter grows immensely as a manager and a thinker. In fact, he can never go back to naively assuming so much when confronted with a new problem.

Desi was beginning a personal transformation in his way of thinking. It would never have even started if his boss had simply accepted his initial A3 or had just made some minor edits. It was the deliberate feedback and challenges by Ken that forced Desi to go back and question his assumptions and approach over and over. Ken had a general picture of the A3 process and what he wanted Desi to learn. We rarely can effectively challenge our own thinking. Desi needed Ken to coach him and in fact needs continued coaching, or his start at scientific thinking will atrophy.

A3 Coaching by the Real Leslie in a Payroll Company

The real Leslie, whom NL Service’s lean advisor is modeled after and who was Karyn’s first lean mentor, has evolved an approach to developing leaders through A3 that is very much in the spirit of the Toyota Way. Her goal is to change thinking, not simply deliver one-off business results. She does not assume that she can teach people in a classroom and send them off as experts. Here is how she helped one region within a payroll company go from worst to best on key performance indicators through leadership coaching using A3 . . . and then watched them fall backward.

Each month the payroll company’s corporate office sent out a report of overall performance by branch. There were a variety of KPIs rolled into one that created that list, with high performers at the top and low performers at the bottom.

The region at the bottom that Leslie worked with had about 500 people in total. The senior leader was the regional manager responsible for 10 branches. Each branch had a branch manager and a service manager, for a total of 10 branch managers and 10 service managers for the region. Each branch also had about 10 customer satisfaction supervisors (approximately 100 in total for the region).

The regional manager had previously been in a different position and had worked closely with Leslie, so he already had experience with lean in his operation. When he moved to the regional manager position, he wanted to incorporate what he had already learned and also continue learning. He also wanted to develop the leaders that reported to him from the branches.

His challenge was to raise the scores in his region, which was in last place overall for KPIs measuring business performance (including customer satisfaction) for the country. The regional manager brought together the branch managers and service managers, and Leslie provided a one-day overview of lean learning. They used a Lego airplane simulation and created “practice” A3s from the exercise.

At the end of the day of lean learning, the regional manager tasked each of the branch and service managers to go back to their branches and create A3s focusing on KPIs with the two biggest gaps. The branch manager and service manager were each responsible for their own A3, with coaching from Leslie and the regional manager. The challenge—a formidable one—was to move from last place into first by the end of the fiscal year.

Figure 9.5 shows the A3 for one branch for one of the two KPIs that it was worst on—single dial resolution. Single dial resolution was measured by three sub-KPIs:

Figure 9.5 Single dial resolution A3 for one branch manager

1. Workable percent. Percentage of time in the day that the service reps were available to answer customer calls or were talking to customers

2. Abandoned percent. Percentage of customers who hung up without the phone being answered or without leaving a message

3. Speed to answer. Amount of time from when the phone first rings to when the service rep picks up phone

Leslie held weekly meetings to coach the regional manager. In their coaching sessions, they reviewed the A3s of the branch and service managers that the regional manager would be having one-on-ones with that week.

Each branch and service manager had a biweekly one-on-one in which the regional manager would review and coach them on their A3 and on the rest of the KPIs. For the first quarter, Leslie joined those one-on-ones to evaluate and coach the regional manager on his coaching. As the regional manager’s coaching experience and strength increased, Leslie joined less frequently.

During Leslie’s weekly coaching sessions with the regional manager, she would ask him questions such as “How do you know that?” and “How can you find out?” as she was teaching him the questions to ask the branch managers and service managers. The regional manager, in his one-on-ones with each branch manager and service manager, was coached by Leslie to ask questions about both process and results for the A3s, such as “Were the results of what you did what you expected? What did you learn?”

These questions focused largely on the KPIs and the progress toward the KPIs and whether the managers were following up. We asked Leslie whether the writers of A3s experimented as the improvement kata would suggest. Leslie explained that she was not teaching the improvement kata, but she coached the learners to develop countermeasures which built on one another. As each countermeasure was put into place, the KPI shifted (or didn’t shift). Once the learners saw what happened, the coaching revolved around creating the next countermeasure based on understanding what previously happened. Leslie didn’t use the exact word “experiment”; but she did use the term “PDCA cycle.” She also taught people to use the word “countermeasure,” and not “solution,” as the process was iterative and experimental.

The individual branch and service managers were responsible for developing their people by creating a team and coaching the team members through the work on their A3. The regional manager coached this during the biweekly one-on-ones. The branch and service managers were in the beginning stages of learning themselves and did not suddenly become seasoned coaches, but those who took it seriously were on a fast learning curve.

Finally, the regional manager made follow-up calls each month to check on the status of the KPIs. At the end of each month, after the regional KPI results were available, branch and service managers were responsible for updating the status of their A3s—red, yellow, or green based on KPI targets—in preparation for the call.

Approximately four months into the work, the regional manager called the branch managers and service managers together for another day of lean learning, again led by Leslie. This time, the participants included the 100 or so customer service supervisors, and the group redid the Lego simulation, etc. Many of the customer service supervisors had been working on the A3s with their branch and service managers, and so they already had practical experience. Now they would have the “theory” behind it, and they would be expected to take the thinking and start working on A3s at their levels and teaching the frontline team members.

After six months the region was excited to find that its hard work had paid off. It had moved from last place overall to first place overall. It wasn’t first in every KPI, so it continued to create A3s for those that still had gaps to target. Until . . .

The regional manager was, yet again, moved to another area. Unfortunately, the new regional manager who took over the leadership of the region didn’t have the same interest in lean and didn’t continue the coaching and A3 process . . . so . . .

Over the next six months or so, without someone to coach the managers on a continual basis, old habits returned and the branch and service managers stopped using the A3 process . . . and . . .

The region returned to its original position . . . last.

What does this case teach us? We could easily jump to a number of different conclusions:

1. The use of A3 for coaching and learning does not work. After all, it was not sustainable.

2. The whole idea of creating a culture of continuous improvement is not possible in most organizations because it depends on the fragile role of particular leaders.

I would propose a different set of conclusions:

1. It is fragile, unless . . . It does seem fair to conclude that if building a learning culture depends on people leading in a certain way, the culture is inherently fragile unless we develop enough of a critical mass of people who deeply learn the way of thinking to survive changes in leaders.

2. It takes time . . . Six months certainly was not a lot of time to change the habitual way of thinking and alter the leading style of 100 people. It was not enough time to become a new culture, so when the leader driving it stepped away, it disintegrated fast.

3. It did get results . . . As an experiment testing the efficacy of developing people through an A3 process with strong coaching, it was quite impressive. When we perform an experimental intervention, we would like to see that there is a big change from before to after in the treatment group compared with a control group that did not get the intervention. In this case the treatment group went from last to first in a large company compared with the control groups of other regions. This was a convincing result. And the performance of the treatment group falling down when the leadership coaching ended also demonstrates the efficacy of the coaching and learning process. Without that, superior performance ends.

Leslie was working with the opportunities presented to her, which were actually exceptional. It is rare that you start out with so engaged and enlightened a senior leader who provides this opportunity for intensive coaching over a six-month period. Yet even this was not sufficient to create a self-sustaining change in culture. In fact, it can be argued that there is no self-sustaining cultural change—just a culture continually reinforced and rebuilt by passionate leaders.

Managing to Teach: Do We Have the Coaches?

Not all teaching of A3 in real life resembles the intensive coaching that John Shook received or that Leslie was able to provide. Karyn has worked with many organizations and has experienced firsthand the limitations of trying to treat A3 as a classroom training exercise. As Karyn explains:

Many of the service companies that I’ve worked with have “lean training groups” that create “training” materials and courses for the internal lean change agents. Because Managing to Learn is such a powerful story, it is often used as the basis of A3 training courses that the lean training groups put together. Having attended a number of these classes in different organizations, I’ve often been quite surprised at how the rigorous people-development process described in Managing to Learn gets lost in translation in the classes. Here is how most of these classes go:

Before the class, all the attendees are asked to “choose a problem to bring to class” . . . any problem they want. Of course, in Managing to Learn, Desi Porter doesn’t pick his own problem to work on; Ken Sanderson assigns it to him.

When I go to class, I usually find that the “coaching” part of this is going to be “peer to peer” only. The people attending the class—who have absolutely no more knowledge or skill than each other—are going to be practicing coaching each other—in groups. As the class mechanically goes over each section of the A3, class participants take turns trying to “coach” each other through their problems. Unfortunately, since they don’t have deep experience coaching, or understanding of the business conditions of the problems, it’s usually just a disaster . . . what else could it be?

To add to the problems, these classes are often held in a central training facility that the participants must all travel to. How are the participants going to work on their A3s without being able to go to the gemba and see? The result is that the participants sit around conference tables in the training room and discuss “assumptions” they have. This only serves to reinforce the behavior of sitting around in conference rooms discussing assumptions.

Classes wrap up with the instructor tasking the students to “please finish the A3” when they go home. Of course there is usually no expectation that they will have coaching from their manager or anyone else from the lean training group as it will take too much time.

I often hear students as they leave say things like, “Now we really have a much better understanding of A3 thinking and we’ll be able to use A3s to solve problems.”

A3s don’t solve problems . . .

Now in all fairness, Karyn is not saying that the trainers did a bad job on organizing the class or on delivery. The students appreciated the classes because they were well done. But sitting in a conference room, working with fake data, being coached by other beginners, and then going off with no coaching to apply what you have learned is far from the experience John Shook had in Japan . . . like night-and-day difference. Unfortunately Karyn’s experience is all too typical. We acquaint people with the tools and somehow expect the tool itself to make people into great problem solvers.

The A3 is a Toyota tool that the company uses in the context of corrective coaching by an experienced mentor. When A3 gets used in other organizations without this skilled coaching, the probability of A3 developing systematic, scientific thinking and acting is low. The improvement kata and coaching kata provide the structure for bringing novices to a basic level of competence.

The Improvement Kata and Coaching Kata in Services: Sales Example from Dunning Toyota

Dunning Toyota is a family-owned and -operated business that has been part of the greater Ann Arbor community for more than 40 years. One might assume that it follows all the principles of the Toyota Production System and the Toyota Way, but as an independent business it only began learning this from Toyota recently through a pilot project to create express maintenance—dedicating repair bays for rapid turnaround, routine service like oil and tire changes. The company already had strong values to support its customers and respect people, but this had not translated into managers and team members trained in continuous improvement.

In 2014 Dunning Toyota agreed to participate as a host site for a team of students in my graduate course on lean thinking. The students in class, and Dunning Toyota managers at the same time, practiced the improvement kata and coaching kata. Dunning participated again in 2015 and then in 2016, expanding the number of projects and managers trained. One of the 2016 projects focused on the sales process.9 As we all know, sales is not a routine process and will vary with each customer. Yet we will see that it is still a process that can be improved with impressive results. Let’s walk through the steps of the improvement kata using the sales process example.

1. Direction. Dunning’s challenge was “Number 1 in Michigan.” The vision was to become number one in Michigan in new car sales in three years. This was of course too big a challenge for the student group to take on in one semester, but I always advise companies to select a big challenge and then begin learning the improvement kata focused on one part of the value stream with its own challenge. Dunning had experience with the kata, but not in sales. It considered the overall value streams of different customers purchasing cars and decided to focus on what is often the first stage in sales, the phone call to the dealership. The challenge for this process became “making every phone call count.”

2. Current condition. This turned out to be a much bigger part of the improvement project than anyone would have imagined. The general sales manager, Lowell Dunning was leading the activity and exclaimed, “I thought we would just knock off the current-state analysis, but the more we dug in, the more we realized we had no idea what the condition of the process was!”

The dealership had data from new CRM (customer relations management) software and was quite proud of this relatively new system it had purchased. But it soon discovered it was garbage in, garbage out. There were serious problems with data quality because of very basic issues like no common definition of concepts. For example, the business was interested in turning “fresh calls” into sales but there was no common definition of a fresh call. If a husband calls in after his wife had previously purchased a car, is he a fresh call or a referral?

When the process was documented, it became clear that there were a number of handoffs among people all entering data into the CRM. The call came into a receptionist, who entered some data and handed the customer over to a salesperson, who entered some data and handed off the customer to a sales manager, and then the customer might call back any of these people. The result was often inconsistent information or maybe missing information, as one party thought the other had taken care of it.

For the focus on “making every phone call count,” the sales management team needed accurate measures of the process, which required that all participants use a consistent approach to entering data. The management team chose two metrics for “making every phone call count” and needed to establish an accurate baseline for comparison. The management team, with my students’ support, spent a lot of time on measurements of the current condition and found the following:

![]() Fresh calls to appointments. March 16–22: of 39 fresh phone-ins, 24 appointments were made (61 percent).

Fresh calls to appointments. March 16–22: of 39 fresh phone-ins, 24 appointments were made (61 percent).

![]() Appointments to actual visits. March 23–29: of 30 appointments made by phone, 14 led to visits (47 percent).

Appointments to actual visits. March 23–29: of 30 appointments made by phone, 14 led to visits (47 percent).

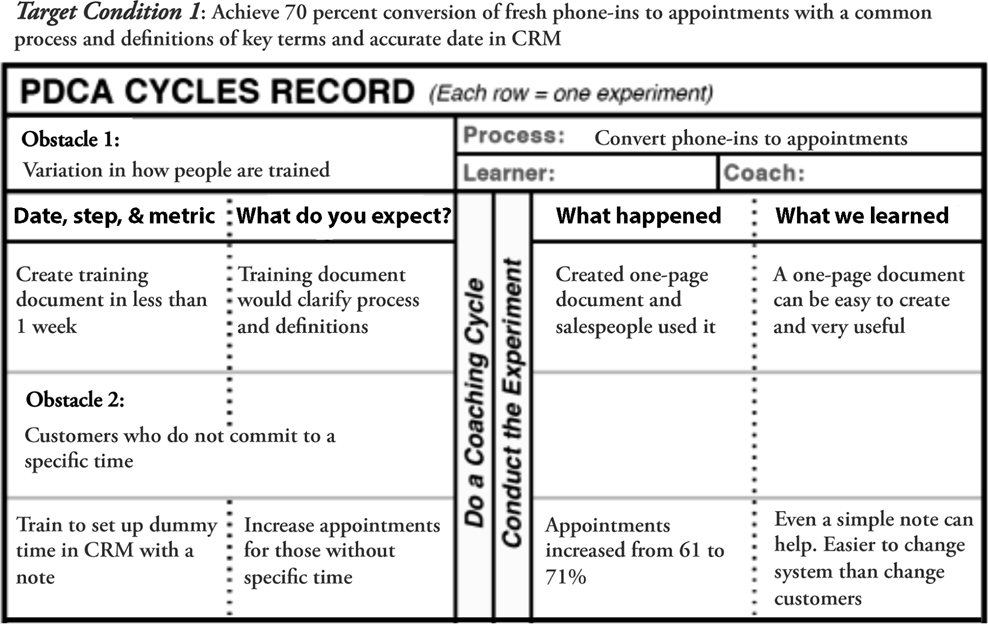

3. First target condition. The process of making every phone call count was broken into two stages: converting calls to appointments and converting appointment to visits. The first target condition was to be achieved in one week: convert 70 percent of phone calls into appointments to visit the dealership, based on a common process and definition of terms, and achieve accurate input of data in CRM.

Obstacles to the first target condition:

![]() Differing definitions of key terms

Differing definitions of key terms

![]() Variation in how people are trained

Variation in how people are trained

![]() Customers who do not commit to a specific time

Customers who do not commit to a specific time

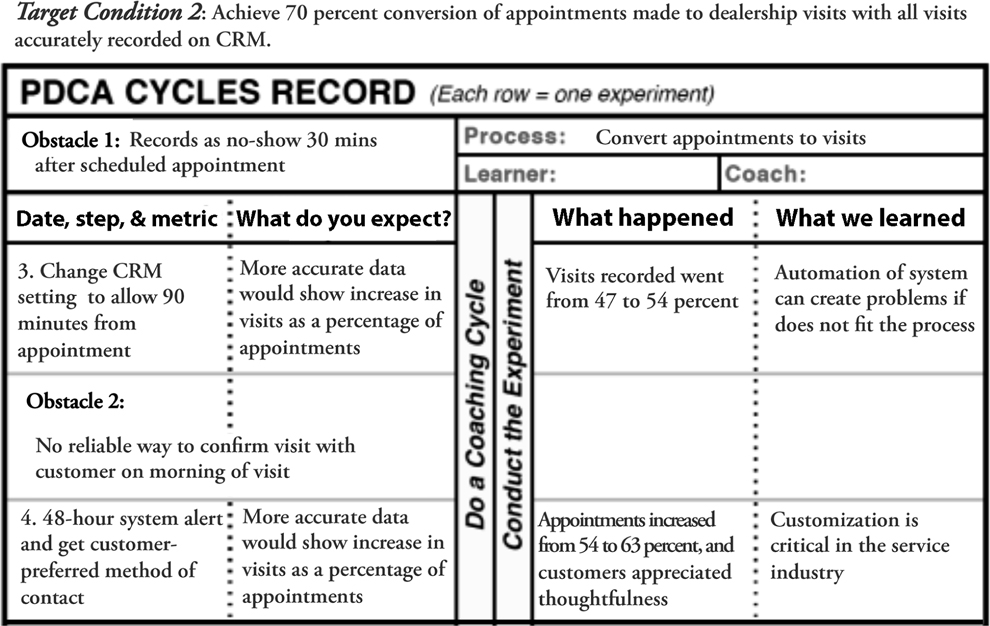

4. Experiments. The PDCA cycles for the first target condition are summarized in Figure 9.6. The team first took on the obstacle that there was “variation in how people are trained.” The sales manager agreed to put together a simple, one-page sheet to define key terms and specify how to enter data into the CRM. He sat down and went through the information on the sheet with each of the CRM users. It worked and only took one week to complete. Each person referred to it when taking phone calls. Everyone concluded that it was simple to follow and useful as a reference.

Figure 9.6 Dunning Toyota sales process experiments to achieve the first target condition

The second obstacle addressed was “customers who do not commit to a specific time.” Oh, those customers are always messing things up! The team analyzed the problem and realized the problem was in the CRM system. The system required the user to select a specific appointment time, or else it would record that no appointment was made and mess up metrics on percentage of calls converted to appointments. The team figured out how to get around the system and trained users on how to set up dummy appointments when the customer did not want to commit to a specific time. This immediately increased appointments made from 61 to 71 percent, achieving the first target condition. More important, the team realized that there is no benefit to blaming the customer, and it is more productive to find something to improve in the system that supports the customer. The team was excited. Two experiments, two successes!

5. Second target condition. One week out: Convert 70 percent of appointments into actual visits to the dealership with all visits accurately recorded on CRM.

Obstacles to the second target condition:

![]() Salesperson had only 30 minutes from scheduled appointment to click button, or CRM would record as missed.

Salesperson had only 30 minutes from scheduled appointment to click button, or CRM would record as missed.

![]() No reliable way to confirm visit with customer on morning of appointment (75 percent of calls go to voice mail).

No reliable way to confirm visit with customer on morning of appointment (75 percent of calls go to voice mail).

6. Experiments. The PDCA cycles for the second target condition are summarized in Figure 9.7. The team first took on the obstacle that the “salesperson had only 30 minutes from scheduled appointment to click button, or CRM would record as missed.” That is, if the user does not push a button within 30 minutes, the system records the customer as a no-show. In reality some customers show up late, beyond the 30-minute window. A simple fix was to increase the buffer time to 90 minutes. Implementing the fix, though, was not simple since nobody at Dunning had made changes in system settings like this before. Fortunately, my students figured it out. The change had an immediate effect, increasing visits recorded from 47 to 54 percent. The Dunning folks realized that not all automation is productive. They needed to be in control of the system, not let the system control them.

Figure 9.7 Dunning Toyota sales process experiments to achieve the second target condition

The second experiment addressed the obstacle of “no reliable way to confirm visit with customer on morning of visit.” The system would ping the receptionist the morning of the visit to remind her that the appointment was coming up. She would in turn call to remind the customer but often the call would go to voice mail. It was too late to do anything about it. Again a simple system change addressed the problem. The system was reset to remind the receptionist 48 hours in advance. The staff also asked the customers how they preferred to be contacted—phone, text, or e-mail? This increased the rate of getting customers into the store from 54 to 63 percent, and some customers commented that Dunning was very efficient and they appreciated that the staff was courteous enough to ask for their preferred communication method.

Dunning Toyota Results and Reflection

As the improvement process progressed, there was a steady increase in calls turning into appointments, visits, and ultimately sales. There was an increase of 27 percent in the calls leading to appointments and a whopping 90 percent increase in appointments leading to visits to the dealership.

Of course, the bottom line is sales. In February 2016, 12 percent of fresh calls were converted to sales. By March, the conversion rate rose to 16 percent, and by April, a solid 22 percent of fresh calls resulted in sales.

There was also a great deal that was learned. Dunning Toyota learned the value of continuous improvement starting with understanding the current condition. When the CRM was first installed, Lowell Dunning was excited about what it did for the business and assumed the process of entering data and using it effectively was just fine. When Lowell and his staff took a close look at the current condition, they found they were wrong on both counts. The process was not well developed, it varied from person to person, and poor data quality meant the CRM was not as effective as they assumed. This new understanding led immediately to experiments that dramatically improved data integrity and the goal of the system, which was to get customers into the showroom and increase sales. Among the lessons from the experiments:

1. Understanding the current condition with reliable and useful metrics is critical to guiding improvement.

2. Technology can support people and a good process, but only if it is effectively used.

3. Technology off the shelf requires continuous improvement to maximize its effectiveness.

4. When it appears that the problem is the customer, one should look carefully at internal systems and processes for improvement.

5. Experimenting by changing one factor at a time leads to deep understanding of how to improve the process.

An astute observation from my students about what they learned borrowed a quote from educational reformer John Dewey: “We do not learn from experience. We learn from reflecting on experience.” They also learned a good deal about lean in sales. They learned that applying generic lean solutions to sales would be a lot of wasted effort, but rather they needed to systematically work toward a challenge, experimenting at each step. They intentionally avoided setting a goal that involved improving how salespeople sold. First, the salespeople were already well trained, and this did not appear to be the bottleneck. Second, this would be a very difficult project for those first learning the improvement kata. Therefore they focused on the systems and processes supporting the salespeople.

The students also got insight about the role of the consultant. They provided coaching support for the core team led by the senior sales executive, but the ownership and ideas came from the Dunning team. This led to a great deal of learning by the Dunning team and a process of learning that is continuing beyond the student project. Among other benefits the salespeople involved and the receptionist felt good about being involved and using their brains to improve the sales process. The receptionist was ecstatic about her involvement because usually “nobody pays attention to the receptionist.” With the various experiences Dunning had with my student projects, it now has assigned all managers to lead improvement activities using the kata.

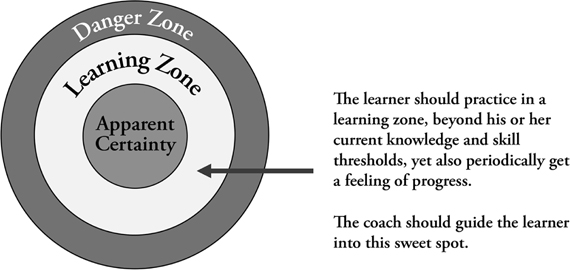

One disappointment to the students was how easily each experiment accomplished the intended goal and ultimately the target conditions. They referred to a graphic by Rother displaying three zones of target setting—apparent certainty, learning zone, and danger zone (see Figure 9.8). The Dunning project was mostly in the zone of apparent certainty. This is not challenging enough to push the learners beyond their current knowledge threshold, and the lack of challenge limits enthusiasm and learning. This is the responsibility of the coach, and in this case I did not coach the new learners sufficiently to push them beyond their comfort zone.

Figure 9.8 Three zones of challenge for the learner

Source: Mike Rother

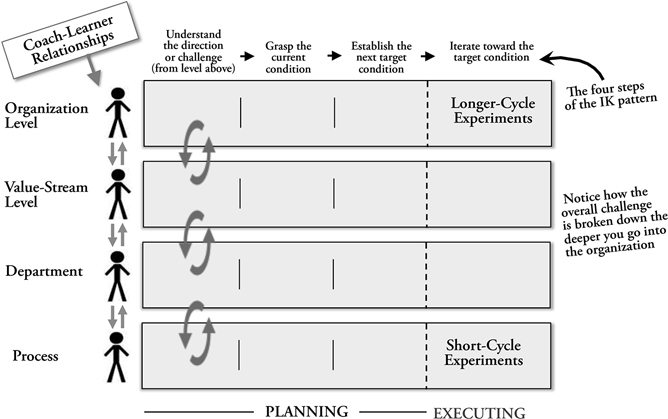

Improvement Kata Pattern and What Each Step Intends to Teach

A mantra of the improvement kata could be “It is all about practicing the pattern.” The IK is designed to teach a meta-skill, which becomes a habitual pattern of how we think and act. Here is one useful explanation of a meta-skill:10

A meta-skill is a kernel of pragmatic knowledge that applies to a wide variety of circumstances including ones you have never directly experienced before. Because meta-skills are portable across many environments, they are extremely valuable. . . .

The meta-skill taught by practicing the routines of the IK is a pattern of scientifically approaching how to navigate your way through obstacles in the direction of a challenge. It applies to the pursuit of virtually any challenge. We saw for example how it was used effectively to improve the sales process at Dunning. Typically we hear statements about how lean does not apply to us because our work is not repetitive, manual tasks. We do not hear that once people get started down the path of the improvement kata. They are focused on improving their process, not trying to imitate someone else’s very different process. As the improvement pattern starts to become a habit, it changes the thinking of people to a new way of approaching any goal.

Consider the life-changing experience of Tyson Ortiz and his wife when they discovered their newborn son had a very rare condition, half a heart. Tyson was being trained in the improvement kata at work and almost naturally began to use the pattern to save his son’s life. Tyson and his wife succeeded, and their son lived to get a successful heart transplant when he turned three, as you will read below.

We should recognize that the underlying pattern of the IK makes assumptions about the elements and sequence of an effective improvement process. It is trying to teach good habits and in the process defines what good habits are. Another representation of the pattern of the IK is shown in Figure 9.9, and our experience is that people find the steps intuitive and logical. We will walk through each step and describe what it intends to teach (summarized in Figure 9.10):

Figure 9.9 Another view of the improvement kata pattern

Source: Mike Rother

Figure 9.10 Core skills taught in improvement kata

1. Direction/challenge. How do my improvement activities contribute to a larger goal that matters to the organization? How do I know what problems to pay attention to and which are lower priority? We discussed strategy and purpose in Chapter 3 as part of the philosophy of the organization. Clarifying the organization’s purpose and defining a clear and distinctive strategy are critical skills to learn. Creating challenge statements that motivate us and help us achieve our purpose, and are consistent with our strategy, is another vital skill set that must be developed. We can think of challenge with the sentence “Wouldn’t it be great if . . . ?” What would be a difference maker? What could you provide your customer that would distinguish you from the competition for years to come?

2. Current condition. Fancy whiz-kid manipulation of data is not enough. Ohno admonished us to learn to deeply observe at the gemba without preconceptions. What is really going on? The more deeply that we observe, the more that current operating patterns, or routines, become clear.

3. Next target condition and obstacles. The key word is “next.” It is not the final target condition, but the next one in the near term on the way to the longer-term challenge. Most people find it pretty easy to state an outcome they desire on key performance indicators. Few are good at defining the operating pattern that they believe will help achieve the outcome. Think of traveling in a time machine to a certain future date (say three weeks out) and describe what you expect to see as the operating pattern and outcomes. Then ask what obstacles stand between where you are and where you want to be.

4. Experiments. This is where Plan-Do-Check-Act comes together as a series of rapid learning cycles. The fun part is fast thinking to brainstorm possible countermeasures and then “just doing it!” The slow thinking part is explicitly stating what you expect to happen before you run the experiment and then after the experiment reflecting on what happened and what you learned. We find that people do not naturally do the slow thinking without good coaching.

Comparing the Underlying Improvement Model of A3 and IK

Managing to Learn teaches us that the intended role of the A3 is as a living document that is rewritten and torn up many times as the student is being coached. The underlying model of improvement at Toyota is very similar to the improvement kata, which is not a surprise since the IK was, in part, modeled after what Rother observed from top Toyota coaches.

On the other hand, if we take the perspective of a novice learning to improve and we look at the A3 problem-solving story, we can infer some differences in the pattern compared with the IK. We have summarized the similarities and differences in Figure 9.11.

Figure 9.11 Underlying improvement process of A3 compared with IK

1. Direction/challenge. The A3 starts with the background. This could be in the form of a challenge statement, but this is not as explicit in the methodology as it is in the IK.

2. Current condition. We typically see in A3 reports the current condition expressed as the baseline on KPIs. These KPIs might include both outcome metrics and process metrics, or they might not. The small space of the A3, and the desire to use graphics, leads to charting a few metrics. The IK storyboard, by contrast includes a whole column for current condition analysis and explicitly asks the learner to look for both outcome metrics and operating patterns.

3. Next target condition and obstacles. The A3 asks for the overall desired project results, but it does not emphasize setting a series of “target conditions” one by one that include outcome metrics and desired operating patterns. Nor does it explicitly suggest an iterative approach to identifying the next target condition—and the next and the next.

A core assumption of A3 thinking is that it is important to find the root cause. Ask why many times, and keep digging until you find the root cause. The IK makes the almost blasphemous assumption that it is not realistic or necessary to find the single root cause. Instead brainstorm “obstacles,” and pick one at a time to overcome through experimentation. As you experiment, you will discover which obstacles are more important to overcome.

4. Experiments. A3 is not explicit about iterative learning through a series of experiments. The learner seems encouraged to identify all the countermeasures and to schedule their implementation, which the IK explicitly avoids. There is no clear pattern of PDCA cycles with predictions and reflection for each cycle in A3. By contrast, the IK’s PDCA cycles record explicitly calls for one experiment at a time, in each case recording expected results, actual results, and what was learned.

One way to think about the improvement kata is by returning to its purpose—to provide starter practice routines to develop positive habits for learning to improve to meet a challenge. In the learning phase it is important to document each step so it is clear to the learners as they are coached. The kata storyboard does this well.

The A3 is a way to document something on one side of one piece of paper to summarize the logical thought process. A good A3 tells a story, whether it is a problem-solving story, a proposal story, or a story presenting the status of a project. Think of the A3 as a snapshot at any point in the improvement process, or a summary at the end, that gives a picture of the whole and is a useful communication vehicle. The kata storyboard is a way of documenting each step of the learning pattern as the project unfolds, and also provides a forum for the coach to keep the student focused on the correct pattern (see Figure 9.12).

Figure 9.12 The A3 documents the whole process, whereas the IK storyboard documents each step of the process

The A3, as it is used to train people at Toyota, and the improvement kata/coaching kata (IK/CK) are aimed at the same purpose: developing scientific thinking skills (achieving clarity of objective, conducting experiments, striving based on facts and data).

The A3 alone is more of a summary of a problem-solving process. If used correctly, the learner is going through it with coaching, and hence practice, at every step. At Toyota the coaching is less structured than the kata, and it is not necessarily daily. There is no formal coaching protocol and no protocol for daily practice. It is up to the coach to determine the frequency and approach. This means the A3 requires a higher level of coaching skill.

The improvement kata and coaching kata make this process more explicit, teachable, and transferable, especially for beginning learners. The purpose of the IK and CK is to systematize the practice—as in sports and music—that’s more implicit in Toyota’s already-strong culture of improvement. Practicing the routines of the improvement kata and coaching kata teaches foundational thinking that makes the A3 effective at Toyota.

Creating Your Own Approach

While the IK is a great approach for beginners, as you mature, you should develop your own approach to improvement that still maintains the high-level pattern. That’s the point of the improvement kata approach. Mike Rother even calls the practice routines of the improvement kata “starter kata.” One experienced group of coaches used elements of the kata, but developed their own approach to teaching Michigan physician practices to improve their processes.

Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan funded a program called the Lean Collaborative Process Initiative (lean CPI), run out of University of Michigan, to help physician practices increase their focus on preventative healthcare. Healthcare reimbursement, particularly from Medicare-Medicaid, is increasingly tied to measurement of quality of care. One element of this is to make full payments contingent on regular screening for early detection of serious diseases. Physician practices are often not very good at this and have a strong incentive to learn how to improve.

Whitney Walters leads the center out of University of Michigan. She describes the challenge these small organizations have, which lack the staff for extensive measurement:

The targets are constantly going up and their processes have to keep getting better. There are so many things being measured that it is becoming difficult for the physician organization to really manage that. They are accustomed to relying on state-provided outcome measures, which are typically sixty days lagging. So you are not getting anything right away that is telling you whether this process is getting better. If I am working on colorectal screening in my office today, how do I know at the end of today how well I performed? So they are looking at their calendars at the end of the day and highlighting those over 50 and checking: Did we ask them for a screen? Did we schedule them for a screen? Did they get the screen?

Whitney’s group was fortunate to have funding for six months just to develop and pilot the approach. The general evolution was to start with a very rigorous and complex process and repeatedly simplify it as they practiced and learned. For example, the group members began with an approach they were trained on—using value-stream mapping. They spent a lot of time tracking the patient, or in some cases the test, through the current-state value stream and then developing a desired future-state map. As Whitney explains:

We were very by the book when we got started. And what we found out was that they just needed to get the gist of what is happening and what is going on in each role. So now we have them pick a type of patient. So for one of the teams they are looking at well visits, so it is going to be someone coming in for a well-patient physical. It is really loose. They do not need precise measures. It is ranges, like how long does it take the patient to check in? 30 seconds to 5 minutes. We had spent a lot of time getting really specific about those things and found that there wasn’t a lot of return on that.

Whitney’s group developed an approach similar to the A3 method Leslie used, but the group members put the information on whiteboards. They found that however much they simplified a step, they needed to simplify it further to be used by office managers and nurses who did not have experience documenting processes and measuring things.

The process started with high-level mapping to see the current state and develop a vision of the future state—the direction. Then the improvement team broke down the problem setting a series of goals and began to measure the current condition using run charts, measuring outcomes and process, cause and effect diagrams, and using simple forms for Pareto analysis of the relative frequency of different causes. They intentionally talked about targets, rather than target conditions, as they found the office managers and nurses found the concept of target condition confusing. At first they had difficulty getting the staff to feel comfortable experimenting. They added the PDCA cycles record and the coaching kata and they could barely slow them down to experiment on one change at a time. It worked, especially the experimentation, unleashing creativity and energy among the office managers and staff. Experimenting took off and percent of people receiving screening went steadily up.

Their largest client was a company with many physician offices, the Bronson Healthcare Group of over 7,800 employees. The client had gone through an earlier phase of lean and designed a standard KPI board and deployed daily management boards everywhere with little coaching. But that did not meet Bronson’s objectives. When the people at Bronson worked with Whitney’s organization, engagement and results went up dramatically, so Bronson replaced the standard boards with the kata approach.

The overall UM model is a series of three learning cycles, each 16 weeks long, with initial training, then Plan-Do-Study-Act coaching sessions, then monthly shared learning meetings. This at first seemed daunting to those at Bronson, but after the first of the three learning waves, the results were so compelling and enthusiasm so high that the most senior leadership asked to be trained. Dr. Elizabeth Warner led the effort inside Bronson, and she explained what happened:

Relatively early in the 2nd wave of training sessions, one of the directors stated, “I am not sure how to best support this work, what kind of training do I need?” This prompted an entirely new curriculum that was developed with University of Michigan, and tested as lean leader training. This was piloted with 6 leaders including the COO of Bronson Methodist Hospital, Vice President of Physician Development, Medical Director of Continuous Improvement Support, System Director of Continuous Improvement Support, and the System Director of Center for Learning. The impact of this training was immense, providing learners the opportunity to practice humility, self-discovery, and personal willingness to change.

The experience changed Dr. Warner’s view of improvement approaches—and in fact, the opportunities within our healthcare systems:

As a physician, being able to look at a process, with a process to really see the patient’s experience, was humbling. To see the confounding variation in our current processes, the elaborate strategies (work-arounds) that we had created, usually for provider-centric processes, and legacy processes and systems which never have been challenged prior to this context because “that’s how we do things” was a goldmine of improvement opportunities. It solidified my commitment to this methodology for life. The American healthcare system is so broken, and I believe that lean thinking, and the principles which can build and drive positive behaviors, will help us rebuild it.

The Role of Coaching in Improvement

I gave a talk and was asked how important coaching is for effective development of problem-solving skills. I answered that a tiny percentage of people can teach themselves basic skills with a book, whether it is playing a musical instrument, learning to bake, or learning to do basic home improvement. For the more than 95 percent of the rest of us, we need someone to teach us, on the job, providing corrective feed-back. Without that, we will run out of steam and stop learning, or we will continue to practice the wrong thing, developing bad habits. It is that simple.

The coach and learner roles are not as explicit in A3 thinking, though clearly that is the intent. There is no explicit coaching kata in the A3, though Toyota has worked to address this internally through OJD training.

What we repeatedly see outside of Toyota is that A3 is introduced in a course and then students are on their own with little or no coaching. Does this in fact lead to people development? In our experience, no.

Without effective coaching any method becomes a blunt tool wielded without skill. Probably the best situation is one-on-one mentoring from the very best, such as learning to make swords from a master or being taught by Ohno on the shop floor. Master coaches will adjust their methods based on the student and the situation at the moment. With novice to intermediate coaches, there is an important role for a more structured approach such as the kata. But these simple kata do not compensate for impatience, lack of persistence, lackadaisical coaching to meet the corporate mandate, etc. Bad or no coaching leads to little learning and skill development.

PRINCIPLE 17: ALIGN IMPROVEMENT OBJECTIVES AND PLANS FOR ENTERPRISE LEARNING

We have learned a good deal about how to coach continuous improvement. Continuous improvement is a skill and mindset of always searching for something better, not randomly, but with a clear direction guiding the search.

An effective search follows a defined meta-pattern. When the direction is clear, we open our mind to the reality of our current condition. Then we do not plan endlessly to imagine the single best solution, and we do not plot a detailed road map to get from here to there. We define a short-term target condition that includes what we want operating patterns to look like and what outcomes we want by a certain near-term date. At that point we think about the obstacles that will get in our way. And finally we start testing countermeasures to overcome the obstacles and reach our next target condition. When we have reached it, we look back to reflect on what we learned and where we now are, then set our next target condition.

Think of climbing a steep mountain, and the overall task seems overwhelming. But we set the next stake a certain distance up, struggle to get there, then reflect on what we learned about the mountain and look ahead to further obstacles and our next step to overcome them. We cannot possibly anticipate in advance all the obstacles we will face. We have to face them one by one. At some point we are on the top of the mountain, and then we search out another mountain to climb.

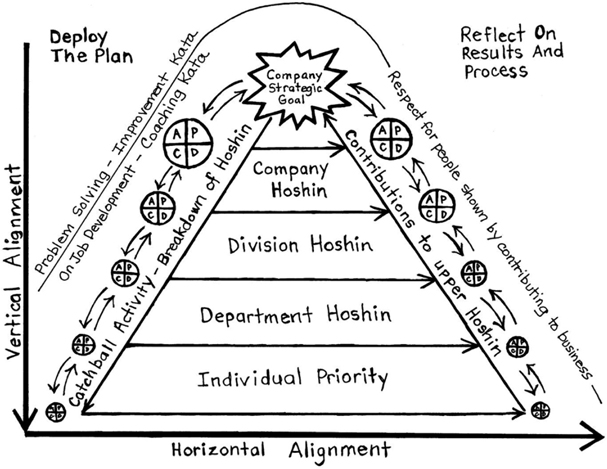

Now that we understand the skills that can help us strive toward a challenge, we can ask, “How do we identify the challenge?” In fact, the challenge will be different for different people in different departments and positions. Therefore we need nested challenges that connect from the very top of the organization to all its parts. That is the role of what in Japanese is called hoshin kanri and in the West is often called policy deployment.

Hoshin Kanri at Toyota

Hoshin kanri was first experimented with in Toyota in 1961 as part of a total quality management program. President Eiji Toyoda identified the need to modernize Toyota’s management practices in order to move from a provider of automobiles inside Japan to a global company. He identified two specific needs:

![]() The need for top management to clarify targets (especially quality) and engage employees

The need for top management to clarify targets (especially quality) and engage employees

![]() A management system that promoted cross-functional cooperation

A management system that promoted cross-functional cooperation

A challenge to mobilize the organization was to win the highly coveted Deming Prize for quality in three years. In 1965 Toyota won the Deming Prize. By 1972, after a decade of continuous improvement, Toyota matured hoshin kanri so that it is now a standard annual practice throughout the company globally.

Toyota works on a fiscal-year calendar from April 1 to March 31. At the beginning of January the company president makes an important speech reflecting on the last year and laying out the vision of the board of directors for the coming year. He enunciates three to five high-level challenges for the year. This leads to a flurry of activity, as these somewhat abstract challenges cascade down through the organization to concrete plans level by level.

For example, the global executive vice presidents of each function, such as sales, are asked what the challenges mean for their organization. How will they support the president’s objectives? What is the current condition? They have intensive discussions, fed by data, with their direct reports, who confer with their direct reports. So at any time there are at least three levels of the organization involved. When the executive vice presidents have committed to their targets and taken a first pass at the means to work toward the targets, the process is then cascaded to the next level down—leaders of the function in each region of the world. It ultimately continues down to the work group.

Some of these goals can be handled within a function, vertically, and others require leading horizontally across multiple functions (see Figure 9.13). For cross-functional work, one leader in one function is assigned the lead role. Learning to lead horizontally is considered the highest level of leadership skill at Toyota. The leader cannot fall back on command-and-control authority to get the team energized and directed toward the challenge. It requires true leadership! In fact as we look at the development of Toyota leaders, we see them starting out by working within one specialty and learning it deeply, then getting leadership responsibility for that function where they have formal authority, and then branching out to horizontal leadership responsibility, all under the watchful eyes of coaches.

Figure 9.13 Hoshin kanri is a top-down and bottom-up learning process

Toyota identifies two skills that are at the center of the hoshin kanri process—problem solving and OJD. We have discussed how Toyota teaches these, and we drew a parallel to using the improvement kata and coaching kata to develop fundamental skills. Toyota sees the hoshin kanri system as further developing these skills. To achieve increasingly difficult challenges as one rises in the organization takes greater mastery of problem solving and OJD.

Catchball in Developing the Initial Plan

Many companies have gotten the memo that hoshin kanri is more than top-down deployment of targets on KPIs. It requires a dialogue between boss and subordinate about the goals for the year. The process of catchball (throwing the ball back and forth) is often used in the planning process so that targets are bought into by each level of management. It is often viewed as a kind of negotiation session, but this is a very small part of the process of coaching and feedback. Each step in hoshin kanri has two objectives: (1) Get results aligned to the company needs. (2) Develop people. The catchball process is part of developing people. It begins in the planning stage that leads to aligned challenges, but then it continues at least as intensely in the ongoing execution process that follows PDCA.

What happens if we take the hoshin kanri method and introduce it into an organization whose managers rely primarily on formal authority and do not have the skills of scientific thinking? The answer is the same as asking what happens to the A3 report. It does not work like it does at Toyota. Targets get cascaded down the chain as orders, and managers are expected to make the numbers or else. Even if the managers participate in setting the targets through catchball, they are basically helping to create the noose that can be used to hang them. Making the numbers is very different from systematically learning your way toward a challenge through continuous improvement.

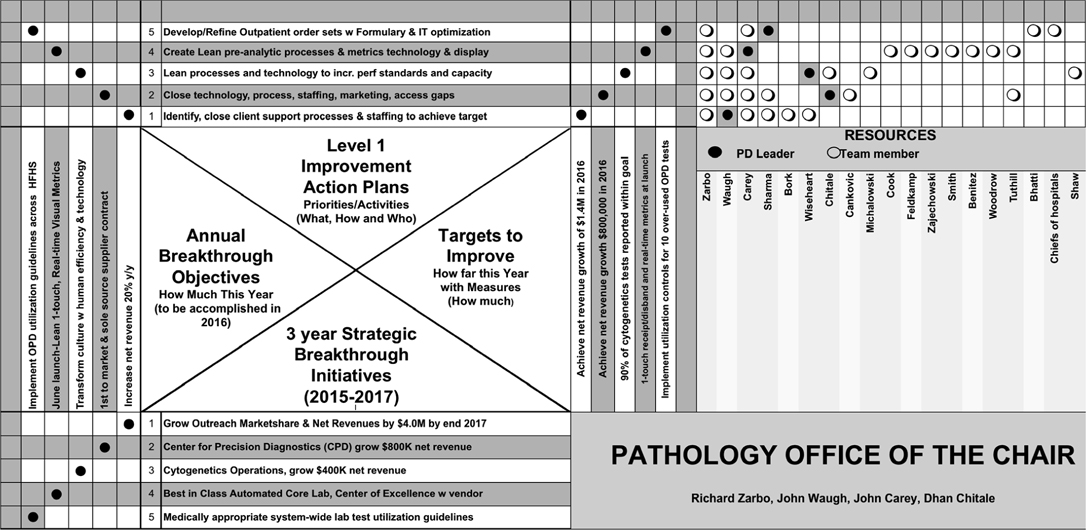

The X-Matrix in Henry Ford Medical Labs

Henry Ford Health System pathology and laboratory medicine under Dr. Richard Zarbo began using hoshin kanri about 10 years into its lean journey. By then all managers and supervisors had been taught problem solving and used it repeatedly, and every manager had an established daily management system with daily meetings to review the status of KPIs.

The X-matrix is to hoshin kanri what the A3 is to problem solving. Both are simple visual representations on one side of one piece of paper. Both can be powerful tools, or they can be superficial information displays. For the Henry Ford labs, building on the years of developing a culture of improvers, it became a powerful tool (see Figure 9.14). It allowed them to focus their improvement efforts toward a common strategic direction.

Figure 9.14 Hoshin kanri X-matrix for Henry Ford Health System pathology and laboratory medicine

Richard Zarbo and his executive team spent weeks meeting, discussing, and crafting their strategy and the first annual plan for the business. The healthcare environment is in turmoil and very stressful for managers trying to navigate through it. Quality care—a basic expectation! Patient safety—a must! Cost reduction—continuous pressure! Cost reduction has been the biggest challenge for the labs because of their dedication to developing a continuous improvement culture.

A foundation of the pact made with employees was that Dr. Zarbo would fight tooth and nail to protect their jobs. They would go forward and work intensely to learn and improve and prosper together. Zarbo managed to hold up his end for many years as other parts of the healthcare system were laying off and shrinking, but at some point he had to succumb to the pressure. It seemed that growth and profitability did not protect any part of the enterprise from mandatory targets for head-count reduction. This did not stop Zarbo from focusing on growth and total cost reduction as a way to reduce any layoffs.

Zarbo’s X-matrix focuses on strategies for growth and profitability. The five 3-year breakthrough initiatives are all focused on strengthening the lab system and growing. For example, one goal is to grow cytogenetics testing by $400,000. This is a new field focusing on the number and structure of chromosomes. Having extra or missing chromosomes is a cause of many chronic diseases. One application is in fetal testing to predict if there will be birth defects or a serious health threat. This is a potential growth area. As Zarbo explains:

Growth and new areas of testing will not protect us from cost reduction targets, but will allow us to get a more meaningful recognition of the lab’s role. Our real goal is growth. Our first target is to grow outreach business, beyond the Henry Ford system, 30 percent year over year. This will provide another million dollars per year in net income. This is the era of personalized medicine, precision medicine. These are tests tailored to the individual based on the DNA profile. We developed a new business starting with personnel recruitment, technology, informatics, marketing, and a business plan. Another goal is to grow the molecular business. We are negotiating to be the sole source provider for the second largest insurer to cover 800 thousand lives. Molecular informatics for a large population. We are not thinking small. This is all survival.