Chapter 8

![]()

Microlevel People Principles: Develop People to Become Masters of Their Craft

They’re (traveling teachers) useless sir. They teach us facts, not understanding. It’s like teaching people about forests by showing them a saw. I want a proper school, sir, to teach reading and writing, and most of all thinking, sir, so people can find what they’re good at, because someone doing what they really like is always an asset to any country, and too often people never find out until it’s too late.

—Tiffany Aching (town witch) pleading the case for a new school to the Duke, in Terry Pratchett, I Shall Wear Midnight

DEVELOPING PEOPLE AS AN ORGANIZING PRINCIPLE

Limitations of Organizational Design Approaches to Change

The high-performance organization approach is humanistic and has led to impressive results. But there is something missing. The starting assumptions seem flawed: that a good design, meaning an elaborate sociotechnical systems plan, can be faithfully executed if only management will get behind it. In this approach, most of the organizational design activity is done in several-day workshops led by external or internal consultants, with senior managers who get “educated” and develop a paper design that they then try to implement throughout the organization.

The Finnish consulting firm Innotiimi began to learn about lean management and saw how it could complement the broad HPO design concepts. In its magazine called Change, it vividly describes what happens when the broad HPO design characteristics are combined with rapid-change methods based on scientific experimentation:1

Just remember a situation (in your private or professional life) where really great things happened: situations where nearly impossible, brilliant results were achieved, where positive energy was high and people felt some kind of flow. What happened? Typically, people describe it like this: “We had a clear, challenging goal to which we all were committed. We felt trust in our team, and each of us acted out of our own personal judgments for success. It was easy to find the right person for the task without any power games. The processes were smooth, without bureaucracy. The focus was on short planning, doing, short reflection, easy adoption and doing again. And at the end, we were proud of our success and were not the same as at the beginning. Our culture, the way we do things, has changed.”

Despite this deep insight, however, Innotiimi continued to focus heavily on the workshop approach. The company added a longer “three-month Rapid Results . . . series of workshops to implement the changes” to the macrolevel workshops. This seems like a useful addition to the theoretical design workshops, but it still is far short of the extended period of daily practice needed to change behavior and mindset. As they describe for one engagement:2

The first workshop was held for the management team. In this one-day meeting, the three percent direct cost decrease, the main organizational framework of the process and the management roles for the project itself were decided. This was followed by functional mini workshops with the key people of each function: three-to-four-hour discussions about the interpretation of the goals for each functional area and the preparation of a process roadmap. . . . In a second half-day management workshop, the potentials found by the functional subteams, who had reviewed their own cost structures, were summarized, and people for the Rapid Results teams were appointed. Afterwards, bi-weekly how-to-workshops were held. . . . Through the initiative, a cultural change started. . . . The Hungarian site achieved savings of 3.3 percent in direct production costs.

In other words the senior management developed a plan for the cost reduction and in a cross-functional team found the cost savings. We certainly believe a well-facilitated team of managers can identify cost savings, but this is far short of any intervention that will deeply change culture. Nonetheless, the macrolevel planning of HPO can provide a framework for microlevel change that is often missing from many lean approaches, which can have the opposite problem of getting caught up in improving specific processes without seeing the bigger, organizational picture. We are not out to criticize this consulting group for which we have deep respect, but short bursts of decisions at meetings is simply not how culture change works. If only cultural change were so quick and easy as creating plans on paper during workshops and then implementing them according to plan.

We believe this common mythology holds many organizations back. There is something missing. And that something, we believe, is the development of the skills and mindset needed for continuous improvement, which focuses on continuously learning, not on rapidly implementing well-defined conceptual plans in short workshop bursts.

We saw in Chapter 7 that Elisa got great value from the work of Kai Laamanen, a consultant of Innotiimi. But his work was specifically focused by Elisa VP Petri Selkäinaho on a specific task—facilitating an executive team to identify the core customer-focused business processes. Then Petri and Elisa people took over facilitating improvement, teaching problem solving, establishing daily management systems, and leading the long and arduous process of changing culture. After six years Petri will tell you that they are still scratching the surface.

Our three microlevel people principles focus on developing people who are coached by leaders with the skills and mindset for improvement (see Figure 8.1):

Figure 8.1 Microlevel people principles

![]() Develop skills and mindset through practicing kata

Develop skills and mindset through practicing kata

![]() Develop leaders as coaches of continually developing teams

Develop leaders as coaches of continually developing teams

![]() Balance extrinsic-intrinsic rewards

Balance extrinsic-intrinsic rewards

From the very beginning, organizations serious about lean transformation need leaders to have the scientific mindset and skills to lead the transformation. As we will see, changing how we think and act is very challenging. We might learn the concepts in training sessions and workshops, but we deeply change how we think and act through repeated action and repeated experiences, and we generally need a coach to guide us. A relatively new approach to developing leaders, introduced in the book Toyota Kata, is a powerful way to develop the scientific mindset. Let’s consider how the fictional company Service 4U came to realize that leaders who were not committed and lacked skills were holding back the lean transformation process.

Services 4U Learns to Develop Leaders Using the Improvement Kata and Coaching Kata

Sam McQuinn and Sarah Stevens had just finished eating lunch in Sarah’s office. It was hard for Sam to believe that almost a year had passed since he left NL Services. Leaning back in his chair, Sam shook his head and said, “Well, what they say about time moving more quickly as you get older really must be right! Looking at the calendar, I can see a year has passed, but it really seems like it’s only been a moment that I’ve been here!”

Sarah laughed, “That’s because we’ve done so much work and made so much progress! At NL Services, even when we’d put in a lot of time and effort doing ‘things,’ it always seemed like we just ended up in the same place—exactly where we started!” Sam laughed as well. Sarah was right. At NL Services, no matter how many long hours he had put in and no matter how many “initiatives” were put in place, the company never seemed to make any progress.

“That’s a great observation,” Sam said as he finished folding up the last bit of paper from his sandwich. “And it’s a great segue into our meeting topic for this afternoon. Just how much progress have we made this year at Service 4U?” Sarah and Sam spent the best part of the afternoon reviewing the targets and results for the different regions: customer satisfaction, client retention, new client growth, and productivity. They were pleased to see that there had been a great deal of progress in many parts of the company. But as they reviewed the graphs for each business unit, they noticed there were a few stars that exceeded expectations, a good number of units that barely made the numbers, and some laggards who seemed hopelessly behind.

“Interesting,” said Sarah as she moved some of the graphs around on the table and lined them up beside one another. “The Northwest Division is on fire, while the Southeast and Southwest Divisions seem to be making steady progress. But the Northeast really seems to be lagging behind. I wonder why that is?”

Sam was silent for a moment reviewing the graphs. “Hold on a minute,” he said to Sarah as he searched on his computer. “Look,” he said, pulling up a copy of the company’s org chart. “I’ve just completed my annual reviews with the regional presidents. Doug Barns, the regional president for the Northwest, just couldn’t stop talking about all the lean work that’s been going on in his regions. And I know that he really ‘knows’ what’s going on—the facts, not just data from reports—and he is always in the regional offices . . . going to the gemba to see for himself. He’s even been out on sales calls with his sales managers and their reps.”

“Yes,” agreed Sarah. “That’s definitely true! I approve Doug’s expense reports, and when I asked him about all the travel, he told me that it was a small price to pay for what he was learning and how he was able to help his managers and supervisors develop themselves and their people.”

Nodding in agreement, Sam went on, “Unfortunately, it doesn’t seem to be the same for the Northeast. Maria Canson, the regional president for the large Northeastern region, just doesn’t seem to be as actively involved in the lean efforts. When I asked her about how she was monitoring her region’s progress and teaching her leaders how to use lean principles, she could give me a few examples of lean projects that she had read reports about, but it didn’t seem to me that she was as committed, as excited, or as personally invested as Doug was.”

Sarah thought about it for a minute. “I think you may be onto something,” she said to Sam. “I’ve noticed the same thing. When I ask her how her people are doing, she seems to give the right kind of answers, but then often follows up with something like, ‘This lean stuff is harder than it looks. I miss the good old days when we just told people what to do and they did it.’ I wonder if she’s really focusing on developing her people’s capabilities—and if she isn’t, maybe that’s one of the reasons her region isn’t making the same sort of progress that Doug’s regions are.”

“Yes,” said Sam, “I agree. And thinking back on it, too, I guess I’ve spent more time with Doug and his leaders because he calls more often for my continuous improvement team’s help. I haven’t spent the same time focusing on Maria and her region either.”

Sam and Sarah were silent for a few minutes. Overall they were pleased with the company’s results, and they were excited that management culture seemed to be shifting to a long-term focus on developing people, but it was also clear to them that most of the company, the regions in which leaders were just playing with lean and were really relying on their past history of traditional command and control, wasn’t progressing like the one part of the company with a passionate leader who was learning to lead with the right combination of understanding lean processes and knowing how to motivate people toward a common goal.

“Sam,” said Sarah, “I think that if we want to continue to make progress—and not end up just like we were at NL Services in the long run—we’re going to have to do some more work on this leadership thing. For the most part, we still have a lot of the leaders we started with, and we certainly don’t have any strategy for promoting or choosing new leaders. And we seem to be focusing our efforts on helping the leader who is already ‘getting it’ and paying less attention to those who don’t. It seems to me that to really become a culture of continuous improvement, we’re going to have to make a plan for developing our leaders so that they can develop their managers and supervisors too. I just wish I knew how to do that. Can’t say that I do right now.”

“Well, Sarah,” said Sam, “I can’t say I know how to do that either. But I bet I know someone who does!”

Two weeks later, Sam and Sarah had a conference call with Leslie Harris, the lean advisor whom they’d grown to trust deeply. Leslie listened carefully to their story. “Great observations and learning,” she applauded Sam and Sarah. “What you’re noticing is a very common problem, and as you’ve found out, unless you have the right leaders in place and they are learning and teaching others, you’re going to see the uneven development that you’re having now: some areas blossoming and some areas stagnating. I’d like to put you in touch with a colleague of mine, Dennis Garrett, who’s very involved in a recent movement in lean toward a practice called Toyota Kata. Toyota Kata is an approach to developing people that fits the way adults learn. Dennis is a real ‘kata geek,’ and I think he’ll be just the right person to help Service 4U progress on leadership development—give the leaders the tools to change instead of just expecting them to figure it out.”

PRINCIPLE 13: DEVELOP SKILLS AND MINDSET THROUGH PRACTICING KATA

The Research Behind Toyota Kata

Mike Rother was my student in a master’s program and worked with me at University of Michigan, but then we went separate ways professionally. I was writing books, speaking, and developing the conceptual basis for the Toyota Way, and he was on the shop floor learning by doing. We both faced the challenge of trying to shift managers from a lean tools orientation to more of a focus on developing people, but in different ways. I wrote about the concepts with case examples. Mike was trying to develop a practical countermeasure. The countermeasure he developed was Toyota Kata. Before we delve deeply into Toyota Kata, let’s consider the problems it was trying to solve.

What Mike observed were a number of weaknesses in lean transformation:

1. Mindless tool deployment. People deployed tools to take out waste without really understanding the reasons for using the tools. They were using “tools for tools’ sake.”

2. No clear direction. There was no clear direction to waste elimination, just a kind of random walk, so the often frenetic activity did not add up to meaningful business results.

3. Lack of scientific method. Although lean professionals all learned about PDCA, few had a really deep understanding of the scientific method behind it; therefore, they were doing a lot of work that had weak planning, checking, and learning.

4. Unclear leadership and accountability. Although improvement teams did this and that, it was not always clear who was responsible for what targets and areas of improvement.

5. Start-and-stop, episodic improvement. There were bursts of improvement activity, followed by business as usual, particularly in companies that used kaizen events as the main deployment mechanism.

There were some positive results from these bursts of activity to deploy tools. Things would get better in certain respects—better flow, less inventory, more organized work patterns, better quality, higher productivity, and on-time delivery, and people were deeply engaged . . . at times. But the process was always jerky, and most of the great ideas produced in those flurries of activity led to changes that degenerated over time. Even when “improvements” led to longer-term changes in the flow of work, there was little adaptation to changing conditions, and eventually the improvements were out of step and less effective. Moreover, management was not really changing the way it thought or acted to support the new systems. Lean became one more improvement program to work on until the next program came along.

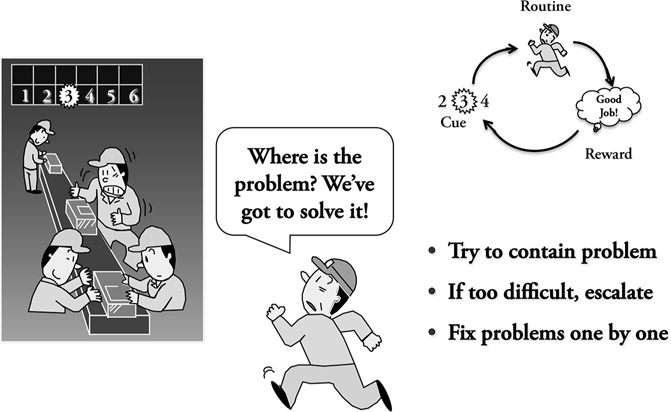

The Root Cause: The Way Our Brains Work

Mike concluded that in most cases well-intentioned people were doing what they thought was right for the company based on existing habits and mindset. He delved into research on neuroscience and cognitive psychology. This was not a Toyota thing; it was a matter of the way humans work and learn. It turns out that the part of our brain that our prefrontal cortex cannot access—the unconscious—plays a far greater role in how we operate day to day than we generally believe. Some estimate 70 to 80 percent of what we do comes from deeply rooted habits that we find difficult to change or do not try hard to change.

The need for habits, or routines, evolved out of the instinct for survival in prehistoric times. People hunting deadly prey did not have the luxury of time to reflect and reason when faced with what they hoped would be their next meal. They had to read and react—see the animal, predict where it would be when the spear arrived, and throw the spear. Those who did this well survived and spawned children, and those who were very contemplative died—and their genes died with them. In modern life there is still a need to read and react, for example in driving. And read-and-react is also very helpful in getting through the day—to get dressed and washed, get to that meeting, get our coffee, perform the routine parts of our daily work, and much more.

Whatever is stored in our brain as routines does not require the use of our most energy-intensive and valuable real estate—the prefrontal cortex. This is our conscious reasoning center where we think through what to say and do. This is where we reflect on what happened and try to learn from it. And it is where we try to control that unruly unconscious part of the brain—most often to little avail. Roughly speaking it is estimated that the brain is about 2 percent of our body volume, yet takes about 20 percent of our energy. The real energy hog is the prefrontal cortex, while much of the brain coasts on automatic pilot. In fact, some argue that what freed us up to develop the human part of the brain that reasons was shifting from moving on all fours to walking erect on two legs, thereby reducing energy for movement and allowing us to develop our brain through evolution. In other words those with developed prefrontal cortexes (the energy hogs) could use their wits to survive and reproduce.3

This is a terribly simplistic explanation, but it provides a general picture, and neuroscientists now know a great deal about how the brain works and are learning more every day. When we are learning something new, we have to forge new connections—synapses —between individual neurons. It is these connections that allow us to remember. These then become our storage for memory and the basis of our semiautomatic routines that we execute. Complex tasks require very dense networks of connections between neurons. Building up these networks of connections takes a lot of work, mainly through repetition. As Mike Rother concludes from his research:4

![]() The brain learns to favor whatever we focus on repeatedly.

The brain learns to favor whatever we focus on repeatedly.

![]() As this information is reinforced through repetition, it becomes wired in the brain and solidifies our thoughts and actions. It becomes who you are. Think about that the next time you’re angry at something or someone.

As this information is reinforced through repetition, it becomes wired in the brain and solidifies our thoughts and actions. It becomes who you are. Think about that the next time you’re angry at something or someone.

![]() Due to these preferred pathways in the brain, we are led into using them again and again, like walking a trail in the snow, which strengthens them even more. Try brushing your teeth with your nondominant hand.

Due to these preferred pathways in the brain, we are led into using them again and again, like walking a trail in the snow, which strengthens them even more. Try brushing your teeth with your nondominant hand.

![]() We can alter our mindset! A way to rewire your brain is to deliberately practice a new pattern. In so doing the existing pathways eventually lose their strength and are replaced with new neural pathways and behaviors.

We can alter our mindset! A way to rewire your brain is to deliberately practice a new pattern. In so doing the existing pathways eventually lose their strength and are replaced with new neural pathways and behaviors.

![]() A sense of optimism will be important. To develop new habits and a sense of self-efficacy through practice, the learner should experience successes and the positive emotions, like those produced by dopamine, that come from them.

A sense of optimism will be important. To develop new habits and a sense of self-efficacy through practice, the learner should experience successes and the positive emotions, like those produced by dopamine, that come from them.

Those of us who have learned to play a musical instrument, in my case classical guitar, know the hard work necessary to build these neural networks. When I begin to learn a challenging piece for the first time, it is downright painful. Twenty minutes of practice and I am spent. My teacher has carefully guided me on how to practice:

1. Break the overall musical piece into small sections, or phrases.

2. Learn to play a phrase at a time, starting with learning individual measures.

3. Play a single measure repeatedly until it is done correctly five times in a row, then move to the next measure, then play the measures together, then move to the next measure, then play the two measures together, and continue to build outward from there into the phrase. Then advance to the next phrase.

4. Play slowly, then more slowly, then more slowly until it is barely recognizable as music. Doing it slowly and correctly is more effective than speeding through it and making mistakes. It turns out our brains will build the pattern just as well slowly and can easily then speed it up when the synapses start getting developed. The brain will also learn the mistakes made when going fast and try to reproduce these “bad habits.”

5. Keep practice sessions short and frequent. Three 20-minute sessions with breaks between are more effective than a continuous 60-minute practice session. The first part of the practice session, when I am most fresh, should focus on learning something new, and then the later part could be playing already learned pieces to enjoy them and to maintain them in my brain.

6. With a degree of mastery of the notes and rhythm of each section, it is time to put it all together and begin focusing on expression.

7. Get corrective feedback from the teacher as often as possible, in my case weekly.

To be honest, what I desire to do is play pieces I already know how to play. This is pleasant, and apparently my brain is doing a lot of self-rewarding through shots of dopamine. However, what I hope to do is to continue to learn, and that is hard and painful. Giving in to playing, rather than learning, means stagnating. I do not develop as a guitar player. And my teacher routinely, year after year, reminds me: “Start with a section that you are having difficulty with and practice it repeatedly, and very slowly, in the way I taught you.”

Kata to Practice Toward Mastery: Sword-Making Example

Kata are the practice routines that allow us to build effective habits. The more I practice a musical piece in the proper way, the more easily I can access what I learned from memory and execute it with little energy expenditure. It is now fun. And it frees me to focus on expression of the music. But I need to know what to practice and how in order to develop these priceless routines. And I need to know what it feels and sounds like to play it in the right way, which I could not do effectively without my teacher’s information inputs.

The Japanese term “kata” is used routinely in the martial arts, which evolved through the master-apprentice relationship. Many people saw the original film The Karate Kid when the master, Mr. Myagi, orders the student, Daniel, to clean his car—wax on, wax off—for many hours.5 He orders him to sand a floor with a similar repetitive motion. He orders him to paint a fence with a repetitive motion. Daniel cannot imagine why he is mindlessly repeating these menial tasks day after day. Exhausted and frustrated, he finally has had enough and confronts Myagi. Finally Mr. Myagi asks him to repeat the motions for sanding a wood floor, for waxing the car, and for painting a fence. He then engages him in a mock fight and tells him to sand the floor, now wax the car, and now paint the fence! Daniel uses the exact same motions to defend himself against Myagi’s attacks. The lightbulb comes on. He was mastering patterns through practice routines that on the surface had little to do with the desired skill but actually were basic skills for karate.

One “karate kid” who decided to submit himself to this process in real life is Pierre Nadeau, a French-Canadian blacksmith, who learned sword making in Japan as an apprentice to a master sword maker.6 After five years of intense study, submitting himself to the teachings of the master, he still came away feeling like an apprentice, and years later he refuses to call himself a master. He realizes how much more there is to learn.

Pierre began his journey with a desired outcome. He loved the swords made by the hands of masters and wanted to learn to make this beautiful product. So he decided from the start that he would do whatever was necessary to develop the skill. He was aware of the rituals in the initial stages of learning from a master, the mindless work that appeared to be meaningless, but he committed to doing whatever he was asked with energy and enthusiasm.

He discovered that we often overemphasize learning concepts with the mind. Think about all those classes and workshops to “explain the concepts and change people’s minds” that most companies start with to begin their lean transformations. Pierre learned that we underemphasize how our mind can learn from what our body does. In fact, the master early on refused to answer any of Pierre’s questions because it would be a waste of time, and it might give the apprentice the impression that hearing an explanation is the same as developing a skill. As Pierre Nadeau explains:

The first aspect of traditional learning in Japan (and, I realized later, anywhere else in the world as far as craftsmanship is concerned) is that one should learn with one’s body instead of one’s head. Narau yori narero. Don’t understand intellectually, but assimilate with your whole body. In the beginning many questions were left unanswered (literally, like you ask a question and my master would keep working like I wasn’t there at all). The idea is that even if he explained it to you in detail, since you haven’t had the experience, it would not make any sense to you other than give you a false feeling of having gotten it. Understanding is actually considered dangerous for it prevents the open-mindedness and full-body experience of someone doing something without any prior knowledge. Even if given the exact recipe, someone with only an intellectual understanding wouldn’t be able to replicate the same sauce. But an experienced chef could guess the right preparation without even knowing the recipe.

Pierre also explains something that I admit was kind of embarrassing to me as someone known as a Toyota Way expert. He says:

If you try to take knowledge (that is, the real learned-with-body kind) and write it down, put it in a box . . . as is done in most school systems nowadays, and you try to pass knowledge around (that is, teach), you’re losing the essence, you’re losing the important subtleties that make this knowledge useful.

And here my main professional accomplishment has been putting the Toyota Way into a box. I can hear my readers, “Now you tell us!” Pierre further explains:

That’s why martial arts (and many other practices) are learned through kata, the actual repetition of the movement, not the explanation of the movement. During kata, the role model (the sensei) watches and corrects; he refines your practice until your kata is perfect.

When writing The Toyota Way to Lean Leadership, I was excited when I discovered the notion of shu-ha-ri, which are three phases of mastering a skill. Pierre describes this as a Western construction that you rarely hear about in Japan and can be misunderstood as a linear process. The idea is that in the shu phase you are copying the role model exactly without questioning. You are imitating a specific pattern. When you practice it enough in the ha stage, it becomes natural, like the basic skills of riding a bike. You do not have to think about the basics—they are now routines embedded in long-term memory. In the ri phase you begin to innovate with new ways of doing things. Pierre agrees you have to start someplace in the shu phase, but after that you could be alternating between the ha phase and the shu phase or even the ri phase and returning periodically to the shu phase to brush up on basic technique.

The shu phase is where the concept of kata comes in—basic practice routines. This he says is also to a degree a Western construction of trying to make sense of Japan, but he likes the idea. As he explains:

I love the expression “fake it until you can feel it.” If you do not agree or you do not understand something you can still do it, just accept to do it, and at some point it may become natural for you to do it and you will be the first to say that this is the best way to do something. This is why learning with the body and learning with the mind are very different. When you learn with your body you have a whole set of senses and emotions that come into play which doesn’t happen when you learn with your mind. . . . The idea of kata is very interesting because instead of trying to convince somebody to adopt managerial or work practices, you get them to fake it at some point or just do it, without asking questions, or maybe without agreeing. But they get to assimilate and do it naturally. . . . They get to assimilate continuous improvement practices into their routines and then reach the goal without any specific effort—it becomes natural for them.

When Pierre was explaining his experience to me, he made one thing clear. To begin his immersion in learning sword making, he needed a high level of trust in the master teacher. Early on he had to prove to the master he was worthy of being taught. Often it seems the other way in the West—the teacher must convince the students he is worthy of teaching. For that reason Pierre sees an advantage in Japanese culture for the type of mentor-apprenticeship model we are talking about. “Trust your mentor, trust your community. People trust those older than them all their life. The craftsmanship culture is alive throughout Japan.”

Skill Development Cycle

By now the notion of 10,000 hours of deliberate practice to mastery is practically a cliché. Who knows if it is 10,000 hours of practice or half that or three times that—what we can be sure of is that it is a lot of practice. But the key word here is “deliberate.” My son, a professional musician, regularly reminds me not to “play through my mistakes.” He hears me practicing, and I continue through mistakes because I am enjoying playing. He thinks I should be working to learn, not playing around. The usual exchange:

JESSE: Hi dad, what are you doing?

ME: Practicing guitar.

JESSE: Oh, that’s nice. What are you trying to learn?

ME: I am practicing a new piece I am working on with my teacher.

JESSE: Oh, so what is it you are working on?

ME: Getting better at the piece.

JESSE: If you keep playing through your mistakes, do you think you will get better?

You can extrapolate and imagine how much fun I am having talking to Jesse. I want to get back to “practicing.” Playing is not practicing in music, sports, or any craft. Playing is executing what you have already learned, incorrect or correct. Deliberate practice means you know what you are trying to learn, what good performance looks like (excellent is even better), and where there are deviations from good performance.

This is where my teacher comes in. His corrective feedback helps me to understand how I am doing compared with an excellent performance. I am not great at giving myself feedback, and I often do not even know how well I am doing until he explains it.

The process of developing new skills and habits can be thought of as a cycle, or some would say a spiral increasingly deepening your skills and understanding. The cycle can be somewhat simplistically thought of as four steps (see Figure 8.2):

Figure 8.2 Skill development cycles

Source: Mike Rother

1. Starter kata. To learn a new skill it helps to have a beginner’s kata—something to practice to develop the pattern in your brain.

2. Practice. You then practice the kata repeatedly, ideally at least daily, in short bursts working to build the complex synaptic structure to make it a routine.

3. Coaching. An experienced coach really helps to get the corrective feedback so you are burning into your brain a good way of executing the routine, rather than practicing mistakes.

4. Self-efficacy. It is unlikely we will put ourselves through grueling practice sessions without getting some type of reward that is best when it is intrinsic—within our brain. This triggers feelings of self-efficacy—I can do this, and I can make a difference. Self-efficacy is the emotional experience that comes from learning with your body, not only your mind. It can trigger amazing sensations as your brain rewards you for a job well done.

In the center of the skill development cycle shown in Figure 8.2 is the hand of a person learning to write. This act is related to a simple exercise that you can do right now. Please sign your name five times and time it from start to finish. How does it feel? Now use your other hand and sign your name five times and time it. How does that feel? If you are like me, you have highly developed neural pathways for your dominant hand and very weak ones for your other hand. For the nondominant hand it probably takes longer, the quality of writing is lower, and it feels strange and frustrating. Now imagine if you deliberately practiced with your nondominant hand every day for a few weeks. I bet it will feel more natural, the time will go down, and the quality will go up.

The Improvement Kata Model

Learning a scientific approach to continuous improvement is similar in many ways to learning to write with your nondominant hand. It does not come naturally, but the habit can be developed with a lot of deliberate practice. Few people can be expected to go through the grueling ordeal that Pierre endured, but we can learn important lessons from him. As Pierre says, you cannot develop deep skills from books, and the learning process cannot be packaged in a box. It is a fluid, dynamic process with a skilled teacher. In this spirit Mike Rother wanted to create effective aids to learning for those of us not willing or able to spend five years at the feet of a master.

These aids are what Rother calls “starter kata,” and as the apprentices are developed and coaches are developed, they will naturally elaborate on the kata. The starter kata come from decades of deep-practice learning and coaching by Mike, as well as five years of research refining the kata by trial and error. Mike observed that the conditions for effective learning involved a coach and a student he called the learner. The coach used practice routines, kata, to teach the learner step by step. Without a coach or practice routines, the student will tend to fall back to bad habits.

What Mike came up with fits well the underlying thinking of the Toyota Way. Like Toyota, the improvement kata (IK) and the coaching kata (CK) focus on developing people through actual experience improving processes—learning by doing with a coach. Like Toyota and like the experience of Pierre, the most effective way to develop a mindset, in this case a scientific approach to improvement, is through deliberate practice. Like Toyota, the ultimate goal is respect for people and continuous improvement, including improving ourselves. Where the IK and CK go a step further is in developing explicit practice routines so we can systematically develop both the skills and the mindset. We will discuss the approach in more detail in Chapter 9. We will introduce the model here.

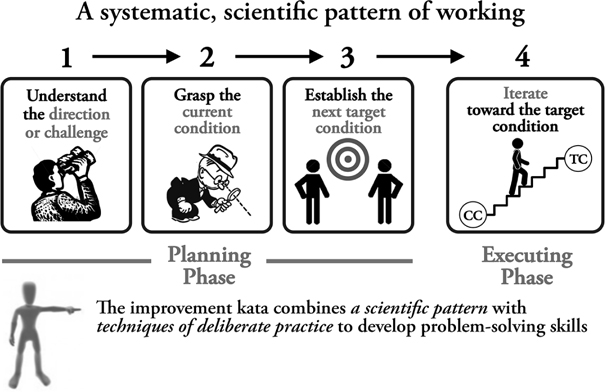

There are four high-level steps in the improvement kata (see Figure 8.3). Together these make up a meta-pattern. By this we mean the kata can be applied to any type of improvement goal, from business goals like quality, lead time, safety, and cost reduction to personal goals like losing weight or stopping smoking. The kata is a higher-level scientific process that is agnostic about the specific content of the problem. It can be applied to any challenge and goals, but following the basic pattern is very important. Let’s consider each step with a simple illustration of trying to lose weight.

Figure 8.3 The four steps of the improvement kata model

Source: Mike Rother

1. Understand the direction or challenge (Plan). This is the first step in planning. In Lewis Carroll’s book Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, the Cheshire Cat and Alice have the following conversation:

“Would you tell me, please, which way I ought to go from here?” asked Alice.

“That depends a good deal on where you want to get to,” said the Cat.

“I don’t much care where—” said Alice.

“Then it doesn’t matter which way you go,” said the Cat.

“—so long as I get SOMEWHERE,” Alice added as an explanation.

“Oh, you’re sure to do that,” said the Cat, “if you only walk long enough.”

It seems like many lean practitioners are taking the same page out of the book:

“Would you tell me, please, which wastes I should chase first?” asked the lean practitioner.

“That depends a good deal on where you want to get to,” said the Cat.

“I don’t much care where—” said the lean practitioner.

“Then it doesn’t matter which waste you chase,” said the Cat.

“—so long as I get SOMEWHERE,” the lean practitioner added as an explanation.

“Oh, you’re sure to do that,” said the Cat, “if you only chase wastes long enough.”

To get beyond randomly “eliminating wastes,” we have to decide where we want to get to. We discussed this in Chapter 3 when we talked about purpose-driven organizations. Asking “What is your purpose?” leads to a general, abstract answer. It is what we might call a vision. A strategy, like that of Southwest Airlines, makes the vision more concrete. But to motivate groups of people toward collective action requires a challenge statement, one that is inspiring, concrete, and measurable, or at least observable.

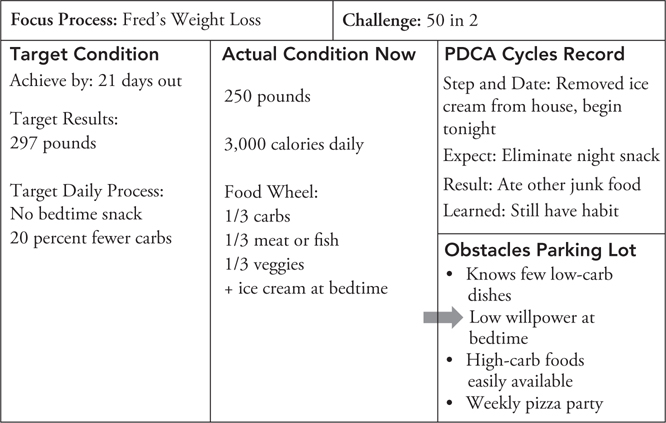

Assume you have a friend, Fred, who wants to lose weight and seeks your help. He has tried in the past with limited success and any weight he lost immediately returned. You have learned about the kata at work and decide to practice using it as a coach helping Fred, the learner, with his weight loss goal. First you ask him what he would like to accomplish. Fred is 55 years old, is 5’11", and currently weighs 250 pounds, and his challenge is to get to and sustain 200 pounds. He decides he wants to do this over a two-year period. There are plenty of quick-results weight loss programs out there, but Fred wants to achieve a sustainable change in lifestyle and read that this is more likely if you change your habits over a longer period of time. You emphasize to Fred the power of defining the challenge in crisp, motivational terms. He comes up with “50 in 2.”

2. Grasp the current condition (Plan). If we want to improve toward a challenging goal, we have to understand our starting point. Can’t we simply measure where we are on the challenge metric? “We want to double sales, and we are at $100 million in sales. The current state is done.” This is useful information but not enough. The question remains: What in the process is producing the current outcome? That is why this is called a current “condition” rather than current “results.”

The concept of a condition versus results is perhaps the most difficult to understand in the IK. We are so used to results-oriented thinking. “What do I need to accomplish to get a good performance review? Give me the target, and I will chase it.” In some senses chasing a target is no better than chasing wastes. What am I likely to try to change if I am making a mad dash for the target? I am likely to go after the low-hanging fruit using methods that I am already good at. “If it worked for me in the past, then it will work for me in the future.”

Unfortunately what has worked in the past in some other condition may not work in your current condition. And this mad sprint to results kills creativity. So we ask in the IK that the learner describe the current condition. Where am I compared with the desired result? What is my current operating pattern?

Understanding the current operating pattern was the goal of Taiichi Ohno’s famous teaching device known as the Ohno circle. He simply would draw a circle on the shop floor and ask you as a learner to stand in it and look. About one hour later he would come by to ask what you see. You describe it, and he says, “Please keep looking.” He repeats this throughout the day. At the end of the day if you have done well, he says, “You are tired. Please go home.” The unlucky students were asked to come back to the circle tomorrow.

What Ohno was teaching was the power of real observation, with a “clear mind.” He wanted the learner to strip away assumptions and see the reality in great detail. He knew this was an experience few had, as most of us run from place to place without really seeing. As you observe, you will understand the operating patterns of all the various actors and the equipment. You will see patterns where at first glance you saw what appeared to be random events.

Back to Fred, he is raring to get started toward his new lifestyle, but as his coach you slow him down a bit. We know he weighs 250 pounds, but there is more to learn. You ask him to establish his current condition by keeping a log of what he eats for one week. He finds he is taking in just over 3,000 calories a day on average. There is about an equal split between high-carb foods, meat and fish, and fruits and vegetables. In addition Fred likes to have a dish of low-fat ice cream before he goes to sleep. He rarely exercises and is in a sedentary job.

Understanding the current condition grounds us in today’s realities. We begin to understand the operating conditions we might have to change to approach the challenge. At this point many “solutions” come to mind, but there is one more critical step in the improvement kata before we run off eliminating wastes and implementing things.

3. Establish the next target condition and define obstacles (Plan). We are still in the planning mode and need a series of shorter-term goals between us and the challenge. The challenge provides direction, but there are many obstacles between us and this big challenge, so we are still wandering through an uncharted wilderness. Expecting to jump from where we are to the challenge suggests an unrealistic degree of certainty in our solutions.

What is perhaps unusual about the target conditions is that we are not going to lay all of them out as a road map to get from here to there. In fact, we are going to start with only one, the first target condition. When we achieve that, we will look at where we are and where we are going and identify the second target condition, and so on.

We need to define a near-term next target condition that we can see clearly from where we are and set an achieve-by date. The key words here are “next,” “condition,” and “achieve by.” It is not enough to say my challenge is to get to a 50 percent customer satisfaction improvement, and my first target condition is a 5 percent improvement. It is like telling Fred who wants to lose 50 pounds that he should start with 5 pounds in the next month. Okay, but how? “Eat less and exercise more,” you answer. The response is likely to be, “I think I knew that, but I still do not know how.”

Assume you are Fred’s kata coach and he is your learner. Instead of giving him useless generic advice, you ask him to set his first target condition. It should include a desired result like a three-pound weight loss but also include the change in desired living pattern—the condition—by some specific date. Generally speaking, novices should have shorter-term achieve-by dates than those with experience in scientific thinking. The more the learners have mastered the kata, the more disciplined they will be in experimenting systematically with that target condition in mind. For a novice, three months out might as well be three years out. So we suggest a target condition two to three weeks out.

Fred sets as his first target condition that he wants to lose three pounds in three weeks. You as a coach ask him what he expects to be different about his eating or exercising pattern in three weeks. You suggest that he think of himself as traveling by time capsule to three weeks from now and describing what he sees in his eating or exercising habits that he believes will help him lose three pounds. It should be a condition he observes, like the current-condition analysis, but after stepping three weeks into the future. He thinks about this and projects that in three weeks he will be going to bed without a snack and eating 20 percent fewer carbohydrates daily. Now he has a target condition:

![]() Target results: Three pounds

Target results: Three pounds

![]() Target daily process: No bedtime snack, 20 percent fewer carbs

Target daily process: No bedtime snack, 20 percent fewer carbs

![]() Achieve by: 21 days out

Achieve by: 21 days out

There is strong evidence from psychology research that Fred has greatly improved his chances of succeeding by defining a short-term target condition. Goal setting generally distinguishes between outcome goals and process goals. A sports psychology definition is that “Outcome goals are a result you’d like to achieve, and process goals are the processes you will need to repeatedly follow to achieve that result.”7 Outcome goals should give clear, measurable outcomes to aim for, but process goals give a desired pattern you can begin to work on right away.

But even this is not enough. There is one more step before execution. We identify obstacles to this first target condition. What will we have to overcome in order to achieve the desired pattern? In this case Fred thinks about it and develops the following obstacle list:

![]() Knows few low-carb dishes

Knows few low-carb dishes

![]() Low willpower at bedtime

Low willpower at bedtime

![]() High-carb foods easily available

High-carb foods easily available

![]() Weekly pizza with friends

Weekly pizza with friends

Finally Fred has completed the initial planning phase and is ready to begin execution. In these coaching sessions with Fred, you have asked him to document his plan on a learner’s story board that tracks the steps of the improvement kata (see Figure 8.4).

Figure 8.4 Learner storyboard for Fred

4. Iterate toward the target condition (PDCA Cycles of Learning). Finally Fred gets to do something. He is excited. He meets with you as his coach, and you explain that he will begin by planning an experiment. Fred screams—“Arghh!!! I thought we were done with planning.” You, as his coach, explain, “We are done with planning where we want to be in the next three weeks, but we are not done with PDCA. We still need to think carefully about each experiment, rapidly try it, and then check on results and think through what we have learned. PDCA is going to be our pattern for execution, but now we are in a rapid PDCA mode. Planning the first experiment involves picking one obstacle and then testing ideas for overcoming that obstacle one by one.” Fred, a bit reluctantly, plays along. He chooses “Low willpower at bedtime.” His first experiment will be to get rid of ice cream from his freezer.

You, as a coach, respond, “Great start, Fred! Please explain to me what you expect to happen when you try this?” Fred says he expects to skip his snack before bed. “Great,” you say. “When can you run this experiment, and when can we next meet to discuss the results?” Fred says it would help to run the experiment for two nights, so let’s meet in two days. You respond, “I look forward to learning about the results of your experiment in two days.”

Two days later you ask Fred how it is going. Standing in front of the learner storyboard, you ask him to remind you about the first target condition. You then ask him what the actual condition is and the obstacle he chose to work on. He reads his first target condition, describes his current condition, and reminds you of the experiment he chose to run and what he expected to happen. You then ask the big question: “What actually happened?” Fred looks disappointed. Without ice cream to turn to, tired and feeling hungry before bed, he found a junk food stash and ate even more calories of sweets and potato chips. “The first experiment failed,” he explained, obviously disappointed. You as the coach respond that no experiment is a failure if you learn from it. “What did you learn, Fred?” He responds that he learned that he did not break the habit of an unhealthy snack before bed but simply made one snack unavailable. You exclaim: “Great learning Fred!!! Now we can plan our second PDCA building on what we learned.”

What we are doing is developing a new pattern, a new habit, of iterative learning. We are learning to experiment, and for each experiment we explicitly define expectations, try one thing at a time, define the results of the experiment, and reflect on what we learned. Real learning happens when we compare expectations with reality. This forces us to confront the fact that there is much we do not know until we try. It starts to eat away at our fear of uncertainty. It begins to reinforce our comfort with failed experiments. In our experience, reflective trial and error will overcome obstacles and get us closer to our goals in a sustainable way.

What Mike Rother concluded from years of studying Toyota, and from practicing what he learned, is that there are limitations to revering Toyota as a model and worshiping “sensei” who in some way learned from Toyota. He explained this to me in a personal communication (March 2016):

In hindsight (and this is all conjecture), it seems like the Lean community had long been practicing a mindset of “certainty,” using Toyota as a mythical organization where everything that glitters is gold. It was actually our two trips to Japan that helped me get beyond this attractive but completely fabricated mental image. How healthy it was to learn that Toyota has all sorts of struggles and messes too. They just approach them a little differently. I think there is a danger in perpetuating a “guru” mindset in the community which, again, makes its followers believe that there is a right answer and that the gurus and Toyota know what that answer is. That’s a comforting, religious-like feeling for people, and probably a comforting “I’m great” feeling for the gurus. You can see this reflected in the behavior and words of many Lean specialists out there.

PRINCIPLE 14: DEVELOP LEADERS AS COACHES OF CONTINUALLY DEVELOPING TEAMS

Often in a seminar I ask, “What are the characteristics of a great coach?” Most of us either have direct experience with a coach we admire or know of a famous coach of a sports team. The groups have no trouble generating marvelous lists that include characteristics like:

![]() Passionate about vision of success

Passionate about vision of success

![]() Follows a disciplined process

Follows a disciplined process

![]() Clear communicator

Clear communicator

![]() Motivates players

Motivates players

![]() Listens to players

Listens to players

![]() Understands the game in detail

Understands the game in detail

![]() Patient

Patient

![]() Firm

Firm

![]() Fair

Fair

Then I ask the group to think about any great coaches among the management team of their organizations. Total silence. We think about management as something different from coaching. Yet what do great coaches do? They get the best out of all of their people and develop them as a team. Don’t we want our managers to do that? Isn’t that important for twenty-first-century management?

Like culture, great leadership is a complex topic. We know it when we see it. Different organizations have different ideas about the ideal leader. Most work hard to identify personality profiles to select their ideal. But are great leaders born that way or developed? Ask a Toyota executive, and that person would probably say both.

Toyota works hard to select people with high potential, but it recognizes this is a hit-or-miss process. Since Toyota employs people over long periods of time, often a full work life to retirement, it can be patient to see how people evolve. The company uses the same skills for deeply observing processes to observe people in actual work situations. Some rise to each challenge living Toyota Way values step by step and get promoted. Others get results, but by working around people rather than developing people—they do not get promoted to further leadership positions. Over time the cream does not naturally rise to the top, but through challenging goals and nurturing by managers as coaches, people learn and develop. Those who develop faster and better and show true leadership skills at the gemba will rise the fastest and furthest.

There is no standard definition of great leadership at Toyota, but the people there know it when they see it. As we discussed in Chapter 2, Toyota Business Practices training is one way to identify those with potential for further leadership roles. It is Toyota’s improvement kata. After that, leaders are expected to coach others to complete a TBP project through On-the-Job Development. This is Toyota’s coaching kata.

Kata to Learn to Coach

The coaching kata that Mike Rother developed exactly parallels the improvement kata (see Figure 8.5). Ideally the coaches will meet with the learners at the storyboard every day and ask them questions about where they are and what they did since yesterday. What the coaches ask them will depend on where they are in the improvement kata. At first it is about the challenge and then moves to the current state, target conditions, obstacles, and PDCA cycles.

Figure 8.5 The coaching kata mirrors the improvement kata

Source: Mike Rother

The challenge is actually provided to the group by management so the learners do not need to be coached about this. There is a fair amount of work to coach the learners through the current-condition analysis, and there are many failure modes. Learners collect and analyze outcome data until the cows come home and do not spend enough time at the gemba observing the facts. Learners do not develop good run charts (timed cycles and observations to identify work timing and patterns). Learners have difficulty figuring out the customer demand rate or takt. The type of process they are working on is not simple and repetitive, and it is not clear how the basic kata tools apply (see Chapter 9 on current condition analysis). At some point the coach needs to get a little directive and take this as an opportunity for some training on how to collect and analyze data. Setting the target condition is even more challenging as we will discuss in the next chapter. There is plenty of opportunity for teaching, and it takes repeated practice until the student gets it.

Once we get past the initial planning stage—challenge, current condition, target condition, obstacles—we move on to execution through PDCA cycles, and the coaching becomes more routine. This repetitive part of the coaching kata is simple and structured. What has become known as the five-question card provides the script for the early learner of the coaching kata (see Figure 8.6). At the very beginning the coach should follow the script exactly, like any kata. Simply ask the questions. Now the student may not have great answers. Getting the student on track may require further clarifying questions, as we illustrate here when the coach is trying to understand what the learner expected to happen in the last step taken:

Figure 8.6 The question card is the standard work for the coach

Source: Mike Rother

COACH: What did you expect?

LEARNER: We expected improvement.

COACH: Good. Can you be more specific about what you expected to improve and by how much?

LEARNER: We expected a 3 percent drop in missed customer calls.

In some cases the learner will be off track on the kata, and the coach will have to bring him back on track. In these cases it is often best to explain in simple terms what is being missed and ask the learner to think about it overnight.

COACH: Which one obstacle are you addressing now?

LEARNER: We are not addressing any specific obstacle. If we solve this problem, we will overcome a number of obstacles.

COACH: In the improvement kata the experiments should be against an obstacle. Can you get with the team and think some more about this so we can return to it tomorrow?

Is that it, you might ask? Simply ask the questions on the card along with a few elaborating questions, and you become an expert coach? Clearly that is not the case. This is still at the starter level where the coach in training is following the kata exactly. As the coach advances, she will learn to develop questions that go beyond the card, as well as approaches to corrective feedback.

The coaching kata is a bit less structured than the improvement kata, by necessity. There are so many situations, it is impossible to account for them all, or even a large percentage. So the stripped-down basics are provided to get the new coach started. Some companies have developed more extensive cards that include notes and clarifying questions. This is great! As you begin your journey, follow the kata exactly. As you mature in your learning by doing, please do modify and expand to improve it for your use. But do not abandon the underlying pattern of improvement.

The difference between clarifying questions and completely new impromptu questions is important. What we are trying to teach through the kata is a pattern—a pattern of improving using the scientific method. It is important to keep the learners focused on the pattern of the improvement kata, or it will not become a habit. If the coaches begin making up questions on the fly, the questions are likely to take the learners, and the coaches, out of the pattern. Often when the coaches feel free to make up their own questions, the questions become directive: “Is that really a difficult enough target condition?” “Did you consider this other solution?” “Was that the real root cause?”

In these cases the coaches were likely trained in some problem-solving methodology and have their own ideas and begin to impose their known methodology, and their ideas, on the learners. It will distract the learners, and the learners will shift into a passive mode, thinking: “Yes, boss. Right, boss. If you wanted it your way, why did you pretend to want to coach me?”

Toyota Work-Group Structure: Layers of Leadership, Not Supervisors

Toyota believes strongly in the power of work groups, but unlike the high-performance organization movement, the company does not believe in self-directed or even self-sufficient teams. Toyota believes strongly in leadership. When a work group is not functioning properly, Toyota management officials almost always will look at weakness in the group leader as the source of the problem. They will focus on developing group leaders as the countermeasure.

Toyota views its managers as leaders who develop other leaders and team members. And the manager of the group leaders will be expected to coach them. The managers’ primary role is to act as coaches. They have figured out the ideal span of control of a work group based on this coaching role. A supervisor who is mainly checking for compliance and dealing with those who break rules might be able to manage 30 or more people. But a leader can coach about five people at a time, so that became the goal of Toyota’s work-group structure. This of course leads to a taller structure, while the rage in businesses today is to flatten the structure. The concept of self-directed teams is attractive if it can mean eliminating a whole layer of management and saving money. Since Toyota believes in leaders developing people, it is willing to pay the extra cost of this apparently nonlean management structure.

I first saw an organizational chart of Toyota’s work-group structure when it was drawn for me by Bill Costantino, one of the first group leader’s in Toyota’s Georgetown, Kentucky, plant. He drew it upside down by usual standards, with hourly production workers (called “team members”) at the top of the chart and senior managers at the bottom (see Figure 8.7). He had been taught this by his Japanese trainers. It represents a version of servant leadership where leaders serve those whom they lead by coaching and developing them. That was how he saw his role at Toyota.

Figure 8.7 Typical organizational structure of Toyota assembly—trim

Source: Bill Costantino, W3 Consulting

It is often said in Toyota that the group leader is like the CEO of a small business. What this means is that the group leader is accountable for everything that goes on in the group, from safety, to discipline, to business results, to human resource development. Nothing is “implemented” in her area that is not led by the group leader. An engineer trying to deploy new technology cannot just walk in and start doing his work. He must inform the group leader, schedule his visits, and serve the work group. Ultimately the members of the work group will be responsible for operating and maintaining any new equipment, and so they must lead its introduction.

The work-group size is about 25 to 30 people, so there is a need for more leaders to get closer to Toyota’s ideal 1:5 ratio. To do this, the company created an assistant role called “team leader.” Team leaders are hourly employees with a natural leadership capability that is cultivated by the group leader. The group leader sees potential and encourages the hourly team member to go to training classes to become a team leader. The group leader finds opportunities to put that team member into leadership positions such as heading up the safety committee or running a quality circle that meets weekly for several months to solve a significant problem. Every day at work there is an on-the-job training opportunity for future team leaders.

Group leaders have formal authority to discipline team members, but team leaders do not. Team leaders normally support a specific number of people doing jobs, usually five to eight. They have done all those jobs and can perform them as needed, for example, if a team member is out sick. They get to the work area early to make sure everything is where it should be, in good working order. They support the team member if she pulls the andon cord, they do quality checks, they collect data for improvement activities, they substitute for team members who need a break, and they stay overtime to clean up and prepare for the next shift. In an ideal situation two of the team leaders are working production on a given day, and two are offline in a support role for the shift.

This model is quite standard in Toyota manufacturing, and variations of this model are used in all functions. Does this mean that it should be copied? Absolutely not! Toyota does not copy it exactly in other parts of manufacturing such as stamping and plastic molding. These are equipment-intensive processes, and the roles and responsibilities are somewhat different. What the company does insist on is following the principles.

Bill Costantino explained further to me that there are certain operating assumptions that are carried out by the work group (see Figure 8.8). Toyota’s assumption in manufacturing is that every car scheduled to be built in a shift will be built. Since Toyota encourages team members to pull the andon when they see an abnormality there is almost always some overtime needed to complete the build schedule. There are no extra people to staff the line if a team member is out for some reason—the team leaders will act as flexible resources for staffing. Team leaders will perform regular, standard checks of the process—standard work checks, tool checks, product checks. Team leaders will perform routine preventative maintenance of tools and equipment. The leaders will train the team members so they know enough jobs to rotate throughout the shift. And the group leader and team leaders will facilitate continuous improvement and develop team members’ improvement skills.

Figure 8.8 Principles behind Toyota’s work-group structure

Source: Bill Costantino, W3 Consulting

Work Groups Need to Be Developed, Not Deployed

When the people at General Motors first attempted to implement work groups like those they saw at their joint venture NUMMI, they copied blindly.8 They exactly copied the structure, but they missed the critical role of leadership development. When GM conducted an internal study to understand how team leaders spent their time, it was found that they focused on emergency relief of workers (e.g., so workers could use the restroom) and quality inspection and repair. When there were no immediate problems and no fires to put out, they went to a back room for a break. In fact, only 52 percent of the time the GM team leaders did anything that you could regard as work, while NUMMI team leaders were actively supporting the assembly-line workers and spent 90 percent of their time doing work on the shop floor. Some of the things the NUMMI team leaders were actively doing:

![]() 21 percent of their time was spent filling in for workers who were absent or on vacation. GM team leaders did this 1.5 percent of the time.

21 percent of their time was spent filling in for workers who were absent or on vacation. GM team leaders did this 1.5 percent of the time.

![]() 10 percent of their time was spent ensuring a smooth flow of parts to the line. GM team leaders were at 3 percent.

10 percent of their time was spent ensuring a smooth flow of parts to the line. GM team leaders were at 3 percent.

![]() 7 percent of their time was spent actively communicating job-related information. This was virtually absent at GM.

7 percent of their time was spent actively communicating job-related information. This was virtually absent at GM.

![]() 5 percent of their time was spent observing the team working, in order to anticipate problems. This did not happen at all at GM.

5 percent of their time was spent observing the team working, in order to anticipate problems. This did not happen at all at GM.

I advised one large multinational manufacturing company, starting when the company first introduced its version of lean. The vice president in charge was very diligent about going to see top lean benchmarks. He told me that he was assembling the company “recipes” (his word) for the production system. With over 90 manufacturing sites throughout the world, he believed a key to success was a set of recipes organized around my Toyota Way principles. Flattering, but I was concerned.

He came back from one trip excitedly exclaiming: “Every success story has in common work groups. They all build around work groups with group leaders and team leaders who are responsible for standard work, visual management, responding to andon, and continuous improvement. We need a recipe for work groups.” At that point the company had supervisors with a span of control of 30 to 40 people who were traditional command-and-control managers. He explained that he had already met with human resources in each country his company operated in to develop legal job descriptions and pay scales for group leaders and team leaders, and he wanted all plants in the world to begin to “roll out work groups” by the end of the year.

By now it should be clear that this is a mechanistic approach to deploying something that is inherently organic. My personal andon was going crazy saying stop, stop, stop! This will fail! As I thought about it, I realized the recipe should not be about putting bodies into job roles, but developing leadership. This personal transformation cannot be mandated. It is something that must be developed, and it takes time and patience—two things missing from this company’s view of deploying lean.

As expected, the teams got “deployed.” Also deployed were very well designed standard visual boards that served as a meeting place for daily huddles and also were used for monitoring suggestions for improvement. I recall touring a plant when an hourly production worker politely asked if he could ask me a question. He pulled me aside and said: “Dr. Liker, I understand the idea behind these teams. But they are not working. The group leaders and team leaders don’t know how to lead, the morning meetings are a joke, and people put up bad suggestions just to get management off their back. Is this really the way teams are supposed to work?” I felt uncomfortable in this situation because I believed he was right and the approach to deployment was fundamentally flawed, but I could not say that. I apologetically explained that senior management was sincerely trying, and there would be growing pains.

Contrast this with the leadership development approach used in the launch of a Toyota service parts warehouse described in The Toyota Way (Chapter 16). Senior leaders reflected on what they had learned in launching a similar warehouse and concluded that they had prematurely assigned group leaders and team leaders, giving them too much responsibility too soon. As a result they developed bad habits, and for years the organization had to backtrack and try to retrain these leaders. The head of the new warehouse explained, “We had one chance to get the culture right in the new warehouse.” He knew there was an early window to do it right, and if the company did not properly develop the leaders, it would mean years of rework.

He took a somewhat radical step within Toyota. He launched the warehouse without team leaders. The work groups started with group leaders, but they acted in a more directive way, like supervisors. The group leaders were intensely taught Toyota Production System principles and were responsible for applying them. Leadership was situational, and as the culture matured it would evolve from directive to participative. As the work groups developed to a certain level of proficiency and potential team leaders emerged, management would consider allowing the group leaders to appoint team leaders group by group as they were ready. Appointing team leaders was something to earn, not an inherent right. It was a multiyear process before all the group leaders had team leaders—years of intensive development.

Applying Principles of Toyota Work-Group Structure: Hospice Nursing Example

Bill Costantino served as a coach to a hospice that served terminally ill patients starting with the executives in charge. They made great progress in the initial stages, but realized their limitations. They had an admirable mission of “Here for Life” and devoted people at all levels. But managers were fighting fires every day and not improving. Each coach could at most develop five learners of the kata at a time, and that was pushing it. Developing coaches would take even longer. It could take years to get through even the management levels of the organization. The leadership team needed a more efficient way. This led them to think about the organizational structure.

The hospice was traditionally organized with anywhere from 13 to 32 nurses reporting to a supervisor. Bill described to the executives the Toyota group leader and team leader system, along with the underlying principles. He emphasized that they should focus on the principles rather than copying the Toyota structure. To his delight the team of executives wanted to approach the problem of organizational structure as a set of kata experiments. They wanted to identify a direction, understand the current condition, set a first target condition, and then experiment.

The initial condition is shown in Figure 8.9. The improvement team found that nursing directors and managers already felt overwhelmed with their workload. They spent all their time chasing problems and never felt like they had enough time. It became clear that layering improvement and coaching onto their existing responsibilities would be too much. If the hospice used a Toyota-like team leader model with a ratio closer to one leader per five team members, there would be time for each manager to become proficient at leading improvement and coaching others to lead improvement.

Figure 8.9 Current condition for the Hospice Care of Southwest Michigan nursing organization

Source: Hospice Care of Southwest Michigan

The hospice decided to focus on the largest group with the largest span of control reporting up to a director of client care (see Figure 8.10). The director, Kristin, had 25 direct reports, including Amy, a home care manager, who had 13 of her own direct reports. Both were overwhelmed with their daily responsibilities of managing mostly by exception and coordinating with other parts of the organization.

Figure 8.10 Kata pilot for the hospice care nursing organization

Source: Hospice Care of Southwest Michigan

The hospice team developed a variety of new organization concepts and in each case got broad input into strengths and possible limitations. The first concept sent up as a trial balloon looked virtually identical to the Toyota model with one team leader for every four team members. This was viewed as promising yet impractical. It would require a significant increase in the number of positions in the organization, and there was already a shortage of clinician talent available, and of course cost was always an issue. The second concept had larger groups with a mix of registered nurses and hospice aides and included a senior leader assisting the team leader. Each team leader would have six to eight registered nurses and six to eight hospice aides. Each team would also have at least one senior registered nurse with a lighter caseload to support the team leader. The nurses chose as their first target condition a third concept, similar to the second concept but without the senior registered nurse assisting (see Figure 8.11).

Figure 8.11 The third concept was chosen as the target condition for the hospice

Source: Hospice Care of Southwest Michigan

The team thought deeply about the responsibilities of their team leader role. The leader was not supporting a repetitive operation located in one place like the Toyota team leader. Clinicians were spread around mostly going to patient’s homes and the caseload varied day to day. They identified the team leader responsibilities in a way that borrowed some ideas from the Toyota model but fit better their situation:

![]() Set the day up for success

Set the day up for success

![]() End the day for success (hand-off to after-hours team)

End the day for success (hand-off to after-hours team)

![]() Provide phone support to frontline clinicians

Provide phone support to frontline clinicians

![]() Complete back-office EMR (electronic medical records) requirements

Complete back-office EMR (electronic medical records) requirements

![]() Maintain Team Quality Board

Maintain Team Quality Board

![]() Report out to leadership team on performance/problems

Report out to leadership team on performance/problems

![]() Complete one continuous improvement project per quarter

Complete one continuous improvement project per quarter

![]() Complete select administrative duties

Complete select administrative duties

A fourth organization concept was put in place in April, 2016 (Figure 8.12). By then they had decided to call the “team leaders” registered nurse managers. It was really a combination of what Toyota calls the team leader and group leader. They had a smaller span of control than the Toyota group leader, but larger than a team leader. They estimated that the ideal number of direct reports for this management position was 10 to 13, and they were close to this ratio at 9 to 14. Notice that their concern about difficulties filling these leadership positions was justified. One of the three management positions was open, with a number of other vacancies, as turnover was common. Also notice that Kristen was “elevated” from director to manager. She discovered she really enjoyed practicing the kata and being closer to the front lines and did not enjoy many of the administrative duties of a director. The turnover meant that whoever was put in the vacant position needed a great deal of kata training. On the other hand Kristen was right there as a resource and one of their most experienced kata coaches.

Figure 8.12 Hospice Care of Michigan, fourth concept

Source: Hospice Care of Southwest Michigan

The results in two areas more then justified all the resources put into learning the improvement kata and coaching kata. First was the preparation for deaths. At some point it is clear when the patient will die. There is a great deal of preparation required in paperwork, funeral arrangements, contacting all the right people, and more. Clinicians were overwhelmed with daily work and most of the time did not do this preparation as shown in Figure 8.13. Through the improvement kata, experiment after experiment, they were able to increase the percent of patients who were properly prepared for from about 20 percent to reach their goal of 80 percent.

Figure 8.13 Number of deaths that were preceded by a zip or on-call report

Source: Hospice Care of Southwest Michigan