Prologue

![]()

The Toyota Way as a General Management Philosophy

The thieves may be able to follow the design plans and produce a loom. But we are modifying and improving our looms every day.

—Kiichiro Toyoda, founder of Toyota Motor Company (after design plans for a loom were stolen from his father’s firm)

THE PROBLEM: MISUNDERSTANDING OF LEAN AND HOW IT APPLIES HERE

Lean (along with its variations, such as six sigma, theory of constraints, lean six sigma, and specialties in different industries like agile IT development, lean construction, lean healthcare, lean finance, and lean government) has become a global movement. As with any management movement, there are true believers, resisters, and those who get on the bandwagon but do not care a lot one way or the other. There are a plethora of service providers through universities, consulting firms, and not-for-profit organizations, and there is a book industry. For zealots like me (Jeffrey), this is, in a sense, a good thing—there are consumers of my message. But there is also a downside. As the message spreads and goes through many people, companies, and cultures, it changes from the original, like the game of telephone in which the message whispered to the first person bears little resemblance to the message the twentieth person hears.

In the meantime, well-meaning organizations that want to solve their problems are searching for answers. What is lean? How do we get started? How do these tools developed within Toyota for making cars apply to my organization, which has a completely different product or service? How do they apply in our culture, which is very different from Japanese culture? Do the tools have to be used exactly as they are used in Toyota, or can they be adapted to our circumstances? And how does Toyota reward people for using these tools to improve?

These are all seemingly reasonable questions, and unfortunately, there are many consultants and self-appointed “lean experts” ready to answer them, often in very different ways. But the starting point should be the questions themselves. Are these the right questions? Though they may seem reasonable on the surface, I believe they are the wrong questions. The underlying assumption in each case is that lean is a mechanistic, tool-based process to be implemented in an organization in much the same way as you would install a new piece of software on your computer. Specifically, the assumptions can be summarized as:

1. There is one clear and simple approach to lean that is very different from alternative methodologies.

2. There is one clear and best way to get started.

3. Toyota is a simple organization that does one thing—assembles cars—and it uses a core set of the same tools in the same way every place.

4. The tools are the essence and therefore must be adapted to specific types of processes.

5. Because lean was developed in Japan, there may be something peculiar about it that needs to be modified to fit cultures outside Japan.

6. Toyota itself has a precise method of applying the tools in the same way in every place that others need to copy.

7. The formal reward system is the reason people in Toyota engage in continuous improvement and allocate effort to support the company.

In fact, none of these assumptions are true, and that is the problem. The gap between common views of lean and the reality of how this powerful thing Toyota has been pursuing actually works is preventing organizations from accomplishing their goals. The Toyota Way, by contrast, is a generic philosophy that can apply to any organization, and if applied diligently, it will virtually guarantee dramatic improvement.1 It is a way of thinking, a philosophy, and a system of interconnected processes and people who are striving to continuously improve how they work and deliver value to each customer. At the heart is a passion to pursue perfection, by striving, step-by-step, toward clearly defined goals. The twin pillars of the Toyota Way are continuous improvement and respect for people.

As you read this book, our goal is to give you a clear understanding of “lean,” or whatever you want to call it. Coauthor Karyn and I start by dismissing the common and simplistic notion that it is a program of using tools to take waste out of processes. If your organization views it this way, you are doomed to mediocre results, until the next management fad takes over to create mediocre results. We will demonstrate the real meaning of what Toyota discovered through discussions of the origin of the Toyota Way, the principles we have distilled, and actual examples of organizations that are pursuing service excellence.

The starting point will be the principles I described in The Toyota Way published in 2004. Those principles were developed as a way of organizing decades of observations of Toyota and direct experiences with many organizations that had struggled on their lean journey. Most of the examples in the original book came from Toyota and mostly from manufacturing, though there were some product development and service examples. The book continues to be widely read (over 900,000 copies sold) across many manufacturing and service sectors. People have been able to abstract the messages beyond manufacturing, but I repeatedly get questions like: “How do these principles apply to my organization in my culture? We are in services, which is not like manufacturing.” While it is impossible to describe every situation you may face, we decided to write this book to bring lean closer to the world of services. We are focusing on service, although as you will see in Chapter 1, the distinction between manufacturing and service is messier than it seems at first glance.

Some of the best examples we have seen of lean in services were kicked off by visits to exceptional lean factories. One of the best in healthcare is ThedaCare in Appleton, Wisconsin. John Toussaint, CEO at the time, had an epiphany after he visited a manufacturer of snowblowers whose president was totally committed to lean. During the visit, Toussaint saw engaged people and a true flow of value through the factory. Certainly this factory was at least as complex as his healthcare systems! He could easily imagine healthcare systems where patients did not queue up and wait, but were flowing through the healthcare experience without interruption.2 He also learned that he needed to lead the transformation personally. As his organizations learned and evolved, patient waiting time was dramatically reduced. Before the transformation, patients would have to make several visits to get required tests, test results, and a diagnosis, and then perhaps they’d have to return an additional time for treatment. The vision became to move from testing to treatment during the very first visit; if this was not possible, at least the patient should leave with a plan of treatment on the first visit. Bringing this vision to reality led to many changes in thinking and in processes including how and where blood samples were analyzed. In the past the lab work was centralized and could take days. Now most tests are completed in on-site clinics in minutes. In fact, after years of improvement, about 90 percent of the lab tests or imaging studies needed in primary care can be completed on-site, and 95 percent of the patients leave with a plan of care in a single visit.

There can be many barriers to learning, however. One may simply be getting the horse to water. Karyn has sometimes had to beg and plead to convince managers in the service organizations she has worked with to visit a manufacturing plant. She recalls one instance, after she succeeded in bringing a group of executives from an insurance company to Toyota, how delighted she was when one leader exclaimed: “The next time people say to us that ‘we don’t make widgets,’ we’re going to send them to Toyota. When they see how complex making a car is, they will run right back to work as quickly as possible, thankful that all they have to do is make some decisions, enter some information into the computer, and out comes an insurance policy!”

Having dismissed the common and simplistic notion that lean is a program centered on tools for taking waste out of manufacturing processes, in this Prologue we wish to convey the deeper meaning of the Toyota Way. We will briefly describe the origin of the Toyota Way within Toyota, how the concept of “lean thinking” fits with the Toyota Way, and what it looks like to pursue it in practice.

THE TOYODA FAMILY: GENERATIONS OF CONSISTENT LEADERSHIP

To understand a company’s culture, we should begin with its roots—the core values of its founders—and Toyota is no exception. Many companies have drifted so far from their roots that the initial values are barely visible, but Toyota has maintained a remarkable degree of continuity of culture over most of a century, starting with its founder, Sakichi Toyoda.

Sakichi Toyoda: Creating Looms and Values

Sakichi Toyoda was born in 1867, the son of a poor carpenter in a rice farming village. He learned carpentry from the ground up, and he also learned the necessity of discipline and hard work. A natural inventor, he saw a problem in the community. Women were “working their fingers to the bone” using manual looms to make cloth for the family and for sale, after a full day of work on the farm. To ease the burden, he began to invent a new kind of loom. His first modification used gravity to allow weavers to send the shuttle of cotton thread back and forth through the weft by manipulating foot pedals instead of using their hands. Immediately, women worked half as hard and were more productive. Sakichi Toyoda continued to make improvement after improvement, some small, some big, and in 1926 he formed Toyota Automatic Loom Works.

He was a devout Buddhist and always lived strong values. One of his favorite books was called Self-Help,3 by British philanthropist Samuel Smiles. Smiles dedicated much of his life to mentoring juvenile delinquents so they could become successful contributors to society. He wrote about the inspiration of great inventors, who, contrary to popular opinion, were not always privileged and gifted students but achieved great things through self-reliance, hard work, and a passion for learning. This fit well the story of Sakichi Toyoda, who raised himself from a poor background as a carpenter’s son and did not appear particularly outstanding, but who through the passion of contributing to others, the hard work of learning the fundamental skills of carpentry, and a clear picture of the problems he wanted to solve, relentlessly made improvement after improvement, each to solve the next problem.

As Sakichi Toyoda grew, his ambitions and contributions also grew. He began to envision a fully automatic loom, and each innovation moved him toward that idea, continually improving toward his vision. He started by helping the women in his family and then the community; then he began helping to industrialize Japanese society, ultimately contributing to all society. He is considered by many to be the father of the Japanese industrial revolution and has been given the title “King of Inventors” in Japan. Along the way, he cultivated himself and his own values. These values eventually become the guiding principles of Toyota Motor Company and included:

![]() Contribute to society.

Contribute to society.

![]() Put the customer first and the company second.

Put the customer first and the company second.

![]() Show respect for all people.

Show respect for all people.

![]() Know your business from the ground up.

Know your business from the ground up.

![]() Get your hands dirty.

Get your hands dirty.

![]() Work hard and with discipline.

Work hard and with discipline.

![]() Work as a team.

Work as a team.

![]() Build in quality.

Build in quality.

![]() Continually improve toward a vision.

Continually improve toward a vision.

Built-in quality was most evident in one of his most influential inventions—the loom that could stop itself when there was a problem. Every innovation by Sakichi Toyoda was problem driven. After the loom was reasonably automatic and could run at a relatively high speed, he noticed that when a single thread broke on the weft to make cloth, the cloth would be defective. A human had to stand and watch the loom and stop it when that happened, which he considered a tremendous waste of human capability. Yet another invention using gravity would solve this problem. This time, Sakichi added a metal weight on the end of a string to each thread in the weft. When a thread broke, this weight would jam the threads and stop the loom. He called this jidoka, a word that was formed by adding to the Japanese kanji for automation a symbol for a human. Thus he had put human intelligence into automation so the loom could stop itself when there was a problem. He later added a small metal flag that would pop up signaling, “I need help.” Jidoka would become a pillar of the Toyota Production System (TPS), conveying the notion of stopping when there is a quality problem and immediately solving the problem.

Based on the teachings of Sakichi Toyoda, the Toyoda Precepts were created, which still guide the company today:

1. Be contributive to the development and welfare of the country by working together, regardless of position, in faithfully fulfilling your duties.

2. Be ahead of the times through endless creativity, inquisitiveness, and pursuit of improvement.

3. Be practical and avoid frivolity.

4. Be kind and generous; strive to create a warm, homelike atmosphere.

5. Be reverent, and show gratitude for things great and small in thought and deed.

Toyota Motor Company and the Toyota Production System

In 1937 Toyota Motors was formed by Kiichiro Toyoda as a division of Toyota Automatic Loom Works. Kiichiro’s father, Sakichi, had asked him to do something to contribute to society, and Kiichiro chose automobiles, a highly risky major challenge. Automobile companies are very capital intensive, and it seemed Toyota was a lifetime behind Ford Motor Company, which at the time was pumping out over 1 million vehicles per year and getting all the attendant economies of scale. Why would a tiny start-up in an obscure part of Japan have any chance of competing, outside perhaps of the protected market in Japan? Like his dad, Kiichiro Toyoda saw a need, an opportunity, and believed in his team. Embodying one of the Toyota principles in starting up this company, Kiichiro, a mechanical engineer, and his team would learn about all the technologies from the ground up and get their hands dirty. This reflected the Toyota principle of self-reliance. Another core principle was announced in a speech Kiichiro gave in which he said: “I plan to cut down on the slack time in our work processes. . . . As the basic principle in realizing this, I will uphold the ‘just in time’ approach.”

What was this “just-in-time” (JIT) approach? Operations management courses in MBA programs would not teach JIT for decades, and there were no books or articles about it. It seems he made it up! And he was not exactly sure what it was. Taiichi Ohno, a brilliant young manager in Toyota Automatic Loom Works, was given the assignment to develop the manufacturing system that would become the next great innovation in Toyota beyond automatic looms—the Toyota Production System. Turning just-in-time from a concept into a working system would be foundational for this new manufacturing system.

The methodology for Ohno’s innovation was the same as Sakichi Toyoda’s for the loom—relentless kaizen. Kaizen literally means “change for the better,” but in Toyota’s case it means systematically working toward a challenge, overcoming obstacle after obstacle one at a time. When Ohno started, he was running the machine shop for engine and transmission components and just began trying things—small experiments—to solve problem after problem. Nothing was worth talking about for Ohno until he actually tried it on the shop floor. The more problems he solved, the more problems were revealed.

For example, the factory was organized in the traditional way by type of process—lathes over here, drilling machines over there—and there were specialist workers for each machining department. Ohno’s idea was to create a cell for a product family and have all the machines set up in sequence to make complete parts, which might mean a lathe, followed by a machining center, followed by a drilling machine and then an assembly process. He wanted the cells to build to takt—the rate of customer demand—with no inventory in the cell except one part here or there as a buffer between machines. This is what we now call one-piece flow. He also wanted the flexibility to adjust the number of people in the cells based on the rise and fall of customer demand without losing productivity. This meant that as demand went down, there would be fewer people, and some would have to operate more than one type of equipment, such as a lathe and a drill.

The concept of a cell building to takt was a magnificent idea but proved to be much harder to implement than Ohno expected. Lathe operators did not want to operate drilling machines and vice versa for the drill operators. His solution? Go to the gemba (where the work is done) every day and spend time with the workers convincing them, showing them, and getting them to try the new system. Over time, they found it was a better way to work, as it produced higher quality with less wasted effort, and it was even safer. Ohno learned a critical lesson—simply thinking of an idea is only the start, and the real work is the time-consuming process of training and developing people through repeated practice so the new system becomes “the way we work.”

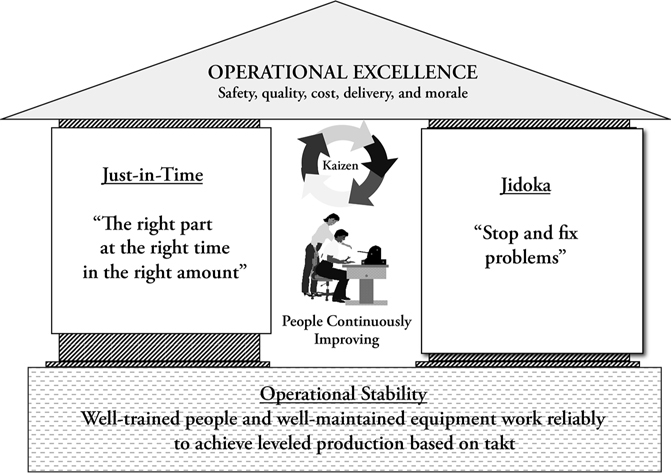

Much later, after the bugs had been mostly worked out, the system was put into writing and was represented as a house (see Figure P.1). The term “system” is not incidental, but very intentional as all the parts are interrelated. The two key pillars were Kiichiro Toyoda’s just-in-time and Sakichi Toyoda’s jidoka (built-in quality). If Toyota was going to work with very little inventory and build in quality at every step, the foundation had to be extremely stable. There had to be reliable parts delivery, equipment that worked as it was supposed to, well-trained team members, and essentially no deviations from the standard. Ideally, the foundation would provide the ability to build consistently to a leveled production schedule, without huge ups and downs, supporting the customer takt. Leveled production would provide a steady rhythm for the factory.

Figure P.1 The Toyota Production System house

To maintain this high level of stability, quality, and just-in-time production would require intelligent team members who were vigilant in noticing the many problems that occurred every day and who took the time to think about and test countermeasures to address deviations from the standard. At the center of the house are highly developed and motivated people who are continually observing, analyzing, and improving the processes. The process gets closer to perfection through continuous improvement by thinking people; therefore, some in Toyota have described TPS as the Thinking Production System.

The purpose of the system is represented by the roof—best quality, lowest cost, on-time delivery, in a safe work environment with high morale. As a system all the parts needed to work in harmony—weak pillars, a weak foundation, a leaky roof, and the house will come tumbling down. Perfect adherence to the TPS vision was never possible, but it provided a picture of perfection that could always be strived for—the purpose of kaizen.

WHAT IS LEAN?

The “lean movement” that has swept across manufacturing and services globally was originally inspired by the Toyota Production System. There are many definitions of “lean,” but let’s start with the term’s origin as a descriptor of organizational excellence. It is not a term you will hear a lot around Toyota. It was first introduced in 1990 in the book The Machine That Changed the World,4 which was the result of a five-year study at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology comparing the American, European, and Japanese auto industries. The researchers consistently found, regardless of the process or metric, that the Japanese auto companies were at that time far superior to the European and American companies in a wide range of areas, including manufacturing efficiency, product quality, logistics, supplier relationships, product development lead time and efficiency, distribution systems, and more.

The message was that the Japanese had developed an integrated enterprise based on a fundamentally different way of looking at the company, work processes, and people that can be best viewed as a new paradigm of management. The word “lean” was suggested by then graduate student John Krafcik, who argued that “lean” means doing more with less, like a superior athlete, and that the Japanese, especially Toyota, were doing more of everything they needed to do for the customer with less of almost everything. It was a holistic concept for the enterprise, not a tool kit for a specific type of process. It applied both to routine work, such as is done on the assembly line, and to very nonroutine work requiring specialized knowledge, like engineering design and sales.

The concept of “waste” in lean is central but often misunderstood. Waste is more than specific actions or objects that need to be eliminated. Waste is anything that causes a deviation from the perfect process. The perfect process gives the customers exactly what they want, in the amount they want, when they want it, and all steps that deliver value do so without interruption.

The concept of “one-piece flow” is the ideal. Each step in the value-adding process does what it is supposed to do perfectly, without the various forms of waste that cause processes to be disconnected by time, space, or inventory. Toyota often uses the metaphor of a free-flowing stream of water without stagnant pools. Of course, one-piece flow requires perfection in everything that is done by people or technology and is therefore an impossible dream. Toyota says this is its “true north” vision, which is not achievable and yet always the goal—striving for perfection while recognizing there is no perfect process.

This ideal, or some would say idealistic, vision arose in Toyota from some very special people, starting with Sakichi Toyoda. We would submit that any organization should desire this state of perfection, regardless of the specific product, service, or culture of the organization. The organization that can deliver pure value to its customers without waste, while continually innovating to improve the product, service, and process, will be successful.

Womack and Jones then built on The Machine That Changed the World with the book Lean Thinking.5 Lean was even more than a highly effective system for delivering value to customers—it was a different way of thinking about the total enterprise. The book made clear that the lean model was not based on Japanese auto companies in general but on Toyota specifically. Toyota had the best performance at the time of any of the Japanese auto companies and was the best model for “lean thinking.”

THE TOYOTA WAY: A PHILOSOPHY AND WAY OF THINKING

The Toyota Way begins with a passion for solving problems for customers and society. To do this requires deep respect for people and their ability to adapt and innovate. Building an enterprise that can withstand the tremendous pressures of the environment, decade after decade, requires a degree of adaptation that can only come from relentless kaizen from everybody. Since people are not born with the spirit of kaizen or the requisite skills, they must be taught. As with any other advanced skill, learning to improve processes requires some direction, relentless practice, and corrective feedback. And the practice cannot be limited to a specialized department of black belts.

If you believe findings by cognitive psychologists, such as Dr. K. Anders Ericcson,6 mastering any complex skill requires “deliberate practice” for 10 years or 10,000 repetitions. Deliberate practice requires being self-aware of weaknesses and knowing the drills to correct them, one by one, and is helped by a teacher who can see the weaknesses and suggest the drills. Ohno had been doing this throughout his career. As he learned, he then taught, not through lecturing, but at the gemba (where the work is done) by challenging students, giving them (often harsh) feedback, and letting them struggle.

After the Toyota Production System was well established in Japan, Toyota had a dilemma. Could this finely tuned system work in a foreign country, without the Japanese workers and culture that seemed to fit so well with its principles? To find out, Toyota did what Toyota does—experimented. The company decided not to go it alone and partnered with General Motors in a 50-50 joint venture called New United Motor Manufacturing Inc. (NUMMI). NUMMI started up in 1984, hiring back over 80 percent of the workers from the GM plant in Fremont, California, that had been closed down in 1982. A reason for closing down the GM plant was horrible labor relations that led to low productivity and quality. With these seemingly discontented workers and the Toyota Way, NUMMI quickly became the best automotive assembly plant in North America in quality, productivity, low inventory, safety—in short, more like a high-performing Toyota plant than a low-performing GM plant. Toyota learned a lot about developing Americans and about creating a culture of trust, and then it decided to start up its own plant in Georgetown, Kentucky. The Toyota Motor Manufacturing Kentucky, or TMMK, plant began production in 1988.

Fujio Cho was selected as the first president of TMMK. If anything, it surpassed the performance of NUMMI, and all seemed well. But Fujio Cho saw a weakness. As the Japanese trainers left and Americans were increasingly taking over responsibility for the plant, they needed explicit training in the Toyota Way. He realized there was more to Toyota’s company philosophy than is captured in the Toyota Production System, which is mainly a prescription for manufacturing. The broader philosophy was learned tacitly in Japan, by “living” in the company and repeatedly hearing the stories and being mentored. What he experienced in America was a lot of variation in the understanding of the core philosophy that Toyota expected all its leaders to embrace.

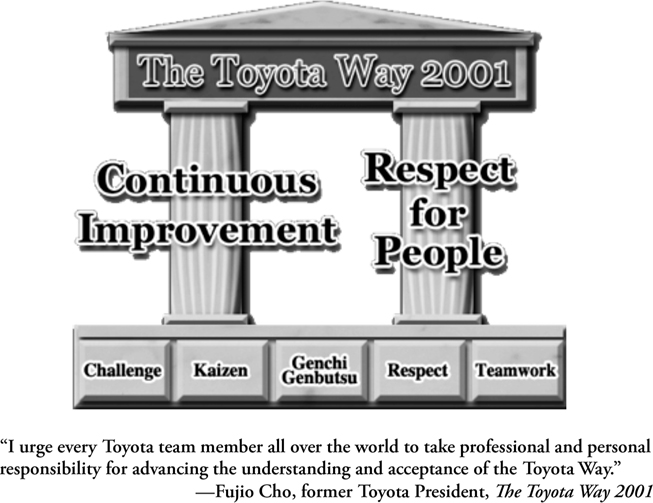

Fujio Cho put together a team who, over a period of about 10 years, worked to capture that philosophy in writing. After many versions, however, the document was still not approved. Toyota works toward consensus, and it could not get consensus. In 1999, when Fujio Cho became president of Toyota Motor Company globally, he revived the effort, this time for the company as a whole. He still struggled to get consensus because others said the philosophy was a living and breathing entity and could not be frozen in time as a document. He finally got agreement to call the document The Toyota Way 2001, with the understanding that it was the best they had developed by 2001 and could be modified in the future (it has not been so far).

It is represented as a house (see Figure P.2) supported by two pillars. One pillar is continuous improvement, and the other is respect for people. Continuous improvement means just what it says: people everywhere constantly challenging the way they are currently working and asking, “Is there a better way?”

Figure P.2 The Toyota Way 2001 house

Respect for people goes far beyond treating people nicely. In Toyota, respect means challenging people to be their best, and that means they are also continually improving themselves as they improve the way they work to better satisfy the customer. Respect for people is intentionally generic. It goes beyond respect for people who are employed by Toyota. It starts with the purpose of the company, which is to add value to customers and society by providing the best means of mobility possible. Respect for society includes respect for the environment, respect for the communities in which Toyota does business, and respect for the local laws and customs of each community.

It is difficult to respect people who are treated as temporary, disposable labor. So Toyota makes a long-term commitment to its employees and to the communities where it sets up shop. Though it does happen, people rarely lose their jobs. Even in the Great Recession, Toyota carried tens of thousands of people globally whom they did not need to make vehicles at the low level of demand. During this period, the company worked on continuous improvement and focused on developing people through education and training, waiting out the bad economy and preparing for the inevitable pent-up demand when things got better. Toyota did not close factories, and this saved local communities from the devastating effects of massive job loss.

The right way to achieve continuous improvement and respect for people is represented by the core values in the foundation of the house. It begins with developing people who will gladly take on a challenge, even when they have no idea how they will achieve it. The process of improvement is kaizen, relentless experimentation, with learning from each experiment informing the next. From 2000 to 2015 Toyota engineering engaged in relentless kaizen to increase the number of vehicles on a common, lightweight platform and make manufacturing processes smaller and more flexible. Results include:

![]() 20 percent reduction in resources for new-model development

20 percent reduction in resources for new-model development

![]() 25 percent improvement in fuel economy with 15 percent more power

25 percent improvement in fuel economy with 15 percent more power

![]() 40 percent reduction in cost of a new plant

40 percent reduction in cost of a new plant

![]() 50 percent reduction in launching a new model, with almost zero production downtime

50 percent reduction in launching a new model, with almost zero production downtime

One hard-and-fast rule of kaizen is to practice it at the gemba, or what Toyota calls genchi genbutsu, meaning, “Go and see the actual place to observe directly and learn.” Toyota leaders are obsessive about direct observation. In fact, they distinguish between data (abstractions of reality) and facts (direct observation of reality). Both are invaluable in understanding the current reality and determining what happens when you intervene in some way.

The final two values focus on people. People work to be the best contributors possible to the team. As stated in The Toyota Way 2001, “We stimulate personal and professional growth, share the opportunities of development, and maximize individual and team performance.” The team is always given credit for accomplishments, while there is always an individual leader accountable for the results of the project.

Then we come right back to respect as the way in which improvement is carried out. This includes respect for stakeholders, mutual trust and responsibility, and sincere accountability. Accountability is described in the following way: “We accept responsibility for working independently, putting forth honest effort to the best of our abilities and always honoring our performance promises.”

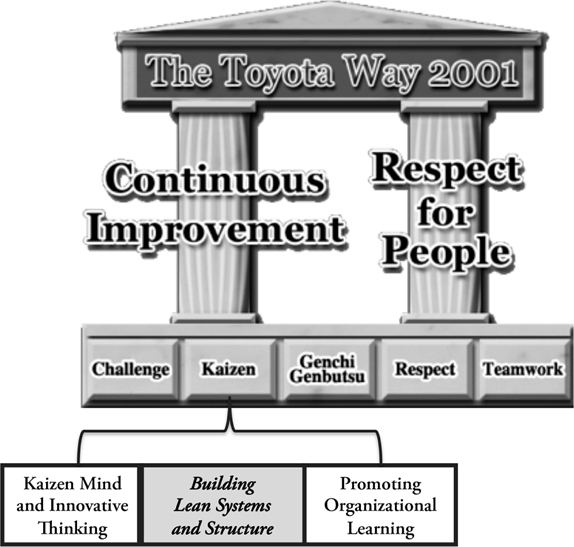

What happened to the Toyota Production System, you ask? What about JIT and built-in-quality and stable processes? In The Toyota Way 2001, these are part of the “lean systems and structure” that contribute to kaizen (see Figure P.3). These are the tools and concepts that we should consider when working to meet the challenging objectives.

Figure P.3 Lean systems are a contributor to kaizen in the foundation of the Toyota Way

At the start of this Prologue, I argued that lean management has lost perspective. It almost seems to be an end unto itself. Companies think, “Let’s implement JIT to reduce inventory” or “Let’s install quality systems to build in quality” or “Let’s put in standard work so that processes are stable.” In the Toyota Way, however, these are powerful tools and concepts to consider when doing kaizen to strive toward excellence. The focus is on the goal and the right way to achieve the goal. Lean systems are side by side with innovative thinking and promoting organizational learning. Collectively, these contribute to kaizen. This is an entirely different mindset than the mechanistic view of implementing tools to get specific—and often short-term—results.

LEARNING THE THINKING OF THE TOYOTA WAY HAS NO RECIPE

As we reflect on the beginning of the Prologue, when we discussed the problem of companies and their many advisors viewing lean as a tool kit for waste reduction, perhaps it is now clearer just how far afield these mechanistic “lean programs” have diverged from the rich tradition developed within Toyota. We hope this book helps guide our readers back on track to the original purpose of the Toyota Way: to create a culture of people continuously improving to adapt and grow through the many challenges of the environment in order to satisfy each customer and contribute to society for the long term.

This is not to say that anyone you meet anyplace you go in Toyota follows all these principles to the letter. Think of The Toyota Way 2001 as a holy document like the Bible or a government constitution. The fact that people deviate from the doctrine, or misapply it, is not an indictment of the doctrine. It is simply that we as humans are far from perfect, sometimes being misinformed, sometimes using bad judgment, rarely being perfectly disciplined, and often giving in to immediate needs and desires. In fact, if we were perfect, we would not need any written or spoken doctrine. We would just be.

The Toyota Way is often spoken about as “true north,” a beacon that guides daily behavior and helps everyone detect whether they are on track or off track. The very basis of continuous improvement is to identify gaps between the actual and ideal and work relentlessly to reduce those gaps, including gaps in our own skills and behaviors.

If we think about trying to improve our bodies physically through exercise and healthy eating, we would all admit that we err from time to time—eating too much or skipping exercise. Our vision may be a great one, but the execution is often flawed. For those who have lost control of their bodies and are obese, it is extremely difficult to even get started. We have so far to go and need tremendous discipline and a great deal of social support. Those in relatively good shape may already have some of the skills and may have developed a degree of willpower. And the more we exercise that willpower to create positive habits, the easier it becomes to follow our daily regimen.

Being mediocre as an organization with few well-defined habits and poorly defined processes is like being obese. It is painful to even think of getting started on the path to true north. But as we try, sometimes fail, but also have some small wins, we get increasingly skilled in overcoming our weaknesses. Success breeds success, and diligent practice is the only true path to excellence.

Toyota is far from perfect, but it is comparatively healthy in many parts of the organization and in many different countries. The company has passionately developed leaders who endeavor to live the values—striving for true north. Middle managers have the social support of senior leaders consistent in their vision of true north—consistent over decades of development. Even for an organization very far from Toyota’s maturity level, it is never too late to start the process of looking with brutal honesty at where you are and where you would like to get to—your true north. Then you need to take a first step, then a second step, and continuously improve your way to the vision.

As you think of how to get started in your organization, review the principles of the Toyota Way. Review the various methods discussed in this book for developing the individual habits and organizational routines that will lead to excellence, such as Toyota Business Practices and OJD. Where will you start? Identify a challenge that will bring your organization to a new level of customer service. Understand the current state. Define the ideal state. Then break down the problem into manageable pieces—step-by-step. For each step, identify a short-term target and begin to experiment toward each target through rapid learning cycles. Every step is worthwhile, successful or not, as long as you learn something. Additional guidance is provided by Mike Rother in his book Toyota Kata.7 He has developed a clear model of the improvement process and practice routines to work your way toward the habit of daily improvement.

If you already have a lean program started, I encourage you to think about that program as part of the current state and compare it with the ideal state. What are the critical gaps in how the program is being executed? How are you doing at developing people in a respectful way? Where is a culture of continuous improvement starting to take root, and where is there stagnation? Investigate personally at the gemba. Learn from a coach. You will begin to understand the true condition of your organization and yourself as a leader.

In this book, Karyn and I will work to give you a clear picture of what lean transformation means in service organizations. As you read, remember, it starts with you.

Jeffrey K. Liker

Author, The Toyota Way

KEY POINTS

We will end each chapter with a summary of key points we hope you will take away and use. These are shorthand bullet points to help you recall what we are trying to teach and also to help you think about how you might use these ideas in your own work. In this chapter we learned:

1. The Toyota Way is a philosophy, way of thinking, and system of interconnected processes and people who are continuously striving to improve how they work and better deliver value to each customer.

2. The Toyota Way begins with a passion for solving problems for each customer and society. The underlying values of challenge, kaizen, genchi genbutsu (go study the actual conditions and learn), respect, and teamwork are the foundation of the system and support the twin pillars of continuous improvement and respect for people:

![]() Continuous improvement means everybody, everywhere, constantly looking for new and better ways to satisfy each customer by experimenting toward challenging goals, striving to reach true north.

Continuous improvement means everybody, everywhere, constantly looking for new and better ways to satisfy each customer by experimenting toward challenging goals, striving to reach true north.

![]() Respect for people means developing people both personally and professionally through challenging them to be the very best that they can be. Respect for people encompasses those who work for Toyota, as well as suppliers, the community, the environment, and the larger world.

Respect for people means developing people both personally and professionally through challenging them to be the very best that they can be. Respect for people encompasses those who work for Toyota, as well as suppliers, the community, the environment, and the larger world.

3. There is no generic “recipe” or one “best-practice way” to mechanically “install” or “implement” lean in an organization. The Toyota Way principles, as described in this book, can, however, help you reflect on your organization, understand where gaps are to your true north, and begin the process of striving toward perfection: delivering the services that your customers want, exactly as they want them, now and for the long term.