2

The Entrepreneurial Spectrum

Introduction

While there are many sources of capital, there are three ways to finance a business: the capital can be invested in the form of debt, in the form of equity, or in a combination of the two. In this book, we will discuss both forms of investment capital. However, be it debt or equity, the most important determinant of whether the capital will be provided is the entrepreneur and his management team. As venture capitalist Richard Kracum of Wind Point Partners said, “During the course of 70 investments we have made in many different kinds of situations over a 16-year period, we have observed that the quality of the CEO is the top factor in the success of the investment. We believe that the CEO represents approximately 80% of the variance of outcome of the transaction.”

The importance of the entrepreneur can be further supported by a statement from Leslie Davis, the director of portfolio management at Equator Capital Partners and former vice president at South Shore Bank in Chicago, who said, “The most important thing we consider when reviewing a loan application is the entrepreneur. Can we trust him to do what he said he would do in his business plan?” Banks, just like venture capitalists, bet on the jockey. Now, the horse (the business) cannot be some run-down creature that is knocking on the door of the glue factory, but ultimately, financial backers have to trust the management team. What are investors primarily looking for in entrepreneurs? Ideally, investors prefer people who have both entrepreneurial experience and specific industry experience.

As Table 2-1 shows, investors grade entrepreneurs as either A, B, or C. They believe that the best entrepreneurs to invest in are the A entrepreneurs, people who have experience as an owner or even an employee of an entrepreneurial firm, and also experience in the industry that the company will compete in.

TABLE 2-1 Investor Ratings of Entrepreneurs

The second most desirable investment candidates are the B entrepreneurs, who have experience either in entrepreneurship or in the industry, but not both.

The last category of people is the least attractive to investors. People who fall into this category should try to eliminate at least one of the shortcomings prior to seeking capital. As one investor said, “There is nothing worse than a young person with no experience. The combination is absolutely deadly.” There is nothing a young person can do about her age except wait for time to pass, but experience can be gained by working for an entrepreneur and/or working in the desired industry. The next best thing that an entrepreneur rated C can do is to hire someone to work on the team who has entrepreneurship and/or industry expertise.

The Entrepreneur

It takes a certain amount of guts, nerve, or chutzpah—whatever you want to call it—to cut the safety net and go out on your own and start a business. No one who does it, including me, has the end goal of burning through his life savings, failing miserably, and dying alone and penniless! In reality, the deck is stacked against the entrepreneur. The failure rate of companies, particularly start-ups, is staggering. A study by the Small Business Administration (SBA) showed the following failure rates for small businesses, which is the lowest in a decade: 49% after 5 years and 67% by year 10.1

True entrepreneurs have remarkable resilience, however, and the statistics suggest that they need it. The average entrepreneur fails 3.8 times before succeeding.2 One such entrepreneur is Steve Perlman, the cofounder of WebTV Networks, which he sold to Microsoft for $425 million. Before his success with WebTV, he had been involved in three start-up failures in a 10-year period. One of the obvious reasons for the high rate of entrepreneurial failure is that it is tough to have a successful product, let alone an entire company. A Nielsen BASES and Ernst & Young study found that about 95% of new consumer products in the United States fail.3 Kevin Clancy and Peter Krieg of Copernicus Marketing Consulting estimated that no more than 10% of all new products or services are successful.4 Another reason for failure is that people are starting companies and then learning about cash flow management, marketing, human resource development, and other such areas on the job. Too many people are learning about what to do when you have cash flow problems when they actually have those problems, rather than in a classroom setting or as an intern with an entrepreneurial firm. This type of training is costly, because the mistakes that are made have an impact on the sustainability of a company. A study of unsuccessful entrepreneurs found that most of them attributed their lack of success to inadequate training.5 The area in which they lacked the most training was cash flow management.6 During tough economic times, the number of business failures will increase because owners cannot pay the bills. At the same time, the number of entrepreneurial start-ups will also generally increase during these periods because people get downsized. There is an important lesson here. All entrepreneurs, prospective and existing, should easily and readily be able to answer the question, what happens to my business during a recession? Businesses respond to recessions differently. For example, one type of business that does well during recessions is auto parts and service because people tend to repair old cars rather than buy new ones. The alcoholic beverages industry also does well during recessions because people tend to drink more when they are depressed or unhappy. Businesses that do not fare as well include restaurants (people eat at home more), the vacation industry, and any businesses that sell luxury items, such as boats. However, just because a business may not fare well during a recession does not mean that a business should not be started at the beginning of or during a recession. It simply means that the entrepreneur should plan wisely, keeping costs under control and maintaining adequate working capital through lines of credit and fast collection of receivables. As an example, BusinessWeek magazine began six weeks after the onset of the Great Depression. Other companies founded during a recession includes General Electric, IBM, General Motors, Disney, Burger King, Microsoft, and Apple.7

On a personal note, about a year after I bought my first business, a lampshade-manufacturing firm, the country went into a recession. The Gulf War started, and people stopped shopping and sat home in front of their televisions watching events unfold. I needed them in department stores buying my lampshades! I remember sitting at my desk at work, holding my head in my hands, when my secretary, Angela, interrupted the silence with a gentle knock on my door. “Are you crying?” she asked. “No,” I answered. “But I should be! I’ve had this business less than a year, I’ve got all this debt, and I’ve got to figure out how to pay it off.” Prior to purchasing the business, I had laid out a specific plan for dealing with a downturn, and we did manage to make it through. But in the spirit of candor, I have to admit that I underestimated how tight business would be. It was ugly. Years ago, former heavyweight champion Mike Tyson was preparing to fight Michael Spinks. A reporter doing a prefight interview with Tyson told him that Spinks had a carefully laid-out plan for beating the champ. Tyson replied, “Everyone has a plan until they get punched in the mouth.” I could not say it better myself. Do yourself a huge favor: be brutally honest with yourself and any investors, and paint the ugliest damn picture you can imagine. Imagine how the economy, competitors, or other conditions could “punch you in the mouth.” Now, tell everyone how your business is going to survive, thrive, and live to ring the cash register another day. Finally, before starting a business and preparing for a recession, the prospective entrepreneur should be able to answer these questions: Where is the recession? Is it yet to come, has it passed, or are we currently in one? The official definition of a recession is “two consecutive quarters of no GDP growth.” The last recession in the United States began in December 2007 and ended in June 2009. The country’s economy typically goes through a recession every five to seven years. During the Reagan administration, the country went 92 consecutive months, or 7.7 years, before going through a recession. Another long period that the country has gone without a recession was during the Vietnam War, with 106 consecutive months (8.8 years).8 As of June 2019, the country has gone 120 months, or 10 years, without a recession. This is peanuts to Australia, which has gone 28 years without a recession!

As noted earlier, failing does not exclude one from becoming an entrepreneur. There are many notable examples of entrepreneurs who have succeeded despite initial failures. For example, Fred Smith had an unsuccessful company before he succeeded with FedEx. Berry Gordy, the founder of Motown Records, started a jazz record shop that went bankrupt. Following this bankruptcy, he went to work for Ford Motor Company on the assembly line to get his personal finances in order, and then left that job to start Motown Records. Henry Ford went bankrupt twice before Ford Motor Company succeeded. And as Henry Ford said, “Failure is the chance to begin again more intelligently. It is just a resting place.”9 Therefore, all prospective entrepreneurs should take heed of the fact that entrepreneurial success is more the exception than the rule. In all likelihood, one will not succeed. But one must simply realize that failure is merely an entrepreneurial rite of passage. It happens to almost everyone, and financiers will typically give the entrepreneur another chance as long as the failure was not the result of lying, cheating, stealing, or laziness. They would rather invest in someone who has failed and learned from the experience than in an inexperienced person. Venture capitalists in Silicon Valley deem failure not only inevitable but also valuable. Michael Moritz, a partner at Sequoia Capital, which invested in the early stages of Apple, Google, Oracle, WhatsApp, YouTube, and Instagram, noted that entrepreneurs who have suffered a setback could be better bets than those who have enjoyed only success.10 Warren Packard, managing director at the Silicon Valley venture capital firm Draper Fisher Jurvetson, is quoted as saying, “Failure is just a word for learning experience. When we meet an entrepreneur who has not been successful, we ask ourselves, ‘Did he learn from past mistakes or is he just crazy?’ As long as an entrepreneur is honest about his abilities, his past does not matter. He has learned some very important lessons on someone else’s dollar.”11 Renowned venture capitalist John Doerr of Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers (KPCB), the Silicon Valley fund that successfully invested in over 800 companies, including Netscape and Amazon.com, said, “Great people are so hard to find that even if one particular start-up fails, you are not tainted for life.”12 And finally, Thomas G. Stemberg, founder and CEO of Staples, Inc., noted, “How you recover is more important than the mistakes you make.”13

Why Become an Entrepreneur?

Over half a million people become entrepreneurs every month.14 A Harris Interactive study found that 47% of Americans who do not currently own their own business have dreamed of starting their own business.15 Now, why do people want to become entrepreneurs? Why has entrepreneurship become so popular? Everyone has a different reason for wanting to start a business. Inc. magazine surveyed the owners listed in the Inc. magazine 500 and found that the number one reason these entrepreneurs gave for starting their own company was to gain the independence to be able to control their schedule and workload. In fact, 40 percent of the respondents indicated that they started their own companies to “be my own boss.”16 Many people become entrepreneurs because they loathe working for others. As one person said, he became an entrepreneur because having a job was worse than being in prison: “In prison: You spend the majority of your time in an 8 × 10 cell. At work: You spend most of your time in a 6 × 8 cubicle. In prison: You get three free meals a day. At work: You only get a break for one meal and you have to pay for it. In prison: You can watch TV and play games. At work: You get fired for watching TV and playing games. In prison: You get your own toilet. At work: You have to share. In prison: You spend most of your life looking through bars from the inside wanting to get out. At work: You spend most of your time wanting to get out and go inside bars! In prison: There are wardens who are often sadistic. At work: They are called MANAGERS!”17

The second most cited reason for becoming an entrepreneur is the sense of accomplishment people achieve when they prove that they can start or own a successful company. Joseph Schumpeter, the originator of the famous “creative destruction” moniker for capitalism, described it well. “Entrepreneurs, he insisted . . . feel the will to conquer: the impulse to fight, to prove oneself superior to others, to succeed for the sake, not of the fruits of success, but of success itself. . . . There is the joy of creating, of getting things done, or simply of exercising one’s energy and ingenuity.”18 Interestingly, most people, young or old, do not become entrepreneurs to become rich. In a survey of high school teens undertaken by the Gallup Organization, 71% of the respondents said that they were interested in starting their own businesses. However, only 26% cited earning a lot of money as their primary motivation for starting a business.19 In the Inc. magazine survey mentioned earlier, “making a lot of money” was only the third most popular reason why entrepreneurs started their own companies.

Finally, a survey conducted by the University of Nebraska indicated that only 6% of business owners believe that the major reason to start a business is to “earn lots of money.”20 What is evident is that for most people, making a lot of money is not necessarily the driving force for becoming an entrepreneur. However, despite this fact, the majority of wealthy people in the United States became rich as a result of being an entrepreneur. The by-product of entrepreneurship is wealth creation. In the United States, 11 million people make up the categories of millionaire, decamillionaire, and billionaire. In 2019, there are a record 607 billionaires. In The Millionaire Next Door, the authors found that 80% of these people gained their wealth by becoming entrepreneurs or as a result of being part of an entrepreneurial venture. For example, one of the country’s wealthiest people, Bill Gates, achieved his wealth by founding Microsoft. Besides Gates, Microsoft has produced an estimated 12,000 millionaires, Google 1,000, and Twitter 1,600.21 Many of these wealthy people are young men and women who were very ambitious, smart, and talented. To further support the wealth creation–entrepreneurship relationship, Forbes reported that three out of five of the Forbes 400 richest Americans were first-generation entrepreneurs.22 But this wealth creation–entrepreneurship relationship is not new. John D. Rockefeller cofounded Standard Oil, the first major US multinational corporation, in 1870. In 1913, his personal net worth was $900 million, which was equivalent to more than 2% of the country’s gross national product. As mentioned earlier, for some people, becoming an entrepreneur was not a choice; rather, they took this route when they were laid off from their jobs. Others started companies with the objective of creating jobs for others.

One entrepreneur who has been selected by Inc. magazine as one of the company builders who is “changing the face of American businesses” is quoted as saying, “I have a business that has the highest integrity in town. . . . People respect me and I support 72 families.”23 For some entrepreneurs, their business is an outlet for their creative talent. Others feel the need to leave behind a legacy that embodies their values. Still others have community or societal concerns that they feel can best be addressed through their company.24 For some people, becoming an entrepreneur is the natural thing to do. They either are the offspring of an entrepreneur or have developed an interest in being an entrepreneur because they were exposed to the business world at an early age. Successful high-growth entrepreneurs who were offspring of entrepreneurs include Berry Gordy of Motown Records; Wayne Huizenga of Waste Management, Blockbuster Video, and AutoNation; Josephine Esther Mentzer of Estée Lauder; Ted Turner of TBS and CNN television networks; and Akio Morita, who left the sake business that his family owned for 14 generations to start Sony. Another high-growth entrepreneur who belongs in this category is John Rogers Jr., the founder of Ariel Capital—a financial management firm that manages billions of dollars. Financial management is in Rogers’s blood. To encourage his son’s interest in business, every birthday and Christmas, John’s father gave his young son stocks as gifts. John’s parents, grandparents, and great-grandparents have always owned their own businesses. In fact, his great-grandfather, J. B. Stafford, was an attorney by training but also owned a hotel in Tulsa, Oklahoma. It burned down in the early 1900s when he was falsely accused of starting a race riot. Instead of giving up, Stafford fled Tulsa, Oklahoma and came to Chicago, where he started his own law firm. Other entrepreneurs start companies to develop a new idea or invention. For example, as discussed later in this chapter, Steve Wozniak, the cofounder of Apple Computer, became an entrepreneur by default. If Hewlett-Packard had not rejected his idea for a user-friendly small personal computer, he probably would not have resigned from the company to start his own business and launch a dramatic change in the computer hardware industry. Another reason why people want to become entrepreneurs is the emergence of role models.

Twenty years ago, the main business role models were corporate executives such as Roberto Goizueta, the legendary CEO of the Coca-Cola Corporation who died of cancer in 1997, and Jack Welch of General Electric. In the entrepreneurship decade of the 1990s, and years that followed, entrepreneurs became primary business role models, the people that everyone wanted to emulate. In a speech titled “Entrepreneurship, American Style,” the American ambassador to Denmark, James Cain, highlighted the reverence that Americans have for entrepreneurs. He notes, “In America, Bill Gates of Microsoft, Steve Jobs of Apple, Fred Smith of Federal Express, and the self-made millionaire down the street, are all considered heroes. In just about every community there are entrepreneurs ‘down the street’ who have succeeded. In fact, it is the ‘ordinary’ millionaire down the street who is often the most celebrated, because people think ‘hey, he is not half as smart as I am. If he can do it, then so can I.’ ” The ambassador continued with an anecdote from Kjeld Kirk Kristiansen, the legendary Danish entrepreneur and former CEO of the Lego Group, demonstrating his point: “He said that over the years fans and customers of Lego’s products have created product conferences and tradeshows where adults, using Lego bricks, showcase their latest impressive creations. He described two such events. One in Berlin, and one in Washington, DC. In Berlin, he said, when he arrived at the conference [he was] treated as just another guest in the room. Nothing special, nothing unique. He contrasted that with the experience in Washington, where, upon his arrival, the 2,000 adult customers who were gathered there treated him as a rock star, as a celebrity, as a hero; gathering around, taking photographs, seeking autographs. He says when he gets to go to America for a show like this; he knows how Elvis Presley must have felt.”25

Inc. magazine conducted a study aimed at assessing the impact of entrepreneurs and their companies on American businesses. A total of 500 entrepreneurs and 200 upper- and middle-level Fortune 500 executives (vice presidents, directors, and managers) were surveyed and asked the same questions. When asked whether they agreed with the statement, “Entrepreneurs are the heroes of American business,” 95% of the entrepreneurs and 68% of the corporate executives agreed. These results were starkly different from the responses given by these two groups 10 years earlier, when 74% of entrepreneurs and 49% of executives had agreed with this statement. Interestingly, 37% of the corporate executives noted that if they could live their lives over, they would choose to run their own companies.26 To scratch this itch, many of America’s most profitable companies continue to devote resources to spurring entrepreneurial activity. Several companies have, in fact, demonstrated this support by creating programs that encourage and assist employees who want to become entrepreneurs. Boeing’s Chairman’s Innovation Initiative, a $200 million in-house venture capital fund, provides employees the opportunities to develop new business ideas from company-developed ideas. Procter & Gamble pushes “open innovation,” encouraging managers to seek new business ideas outside as well as inside the company.27 Other firms, such as Intel, have internal venture capital arms that search for the next breakthrough technologies. Intel has invested more than $4 billion in about 1,000 companies since the early 1990s, maintaining a consistent investment pace through two major recessions. Adobe functions as a sole limited partner in a venture capital fund that it outsources to Granite Ventures in an effort to maintain relationships with the start-up community.28

Layoffs have become a fact of life for American workers. In 2018, despite the growing economy, the corporate carnage was ever present. Major corporations trimming their ranks included AT&T (4,000 workers), HP (5,000 workers), and Deutsche Bank (7,000 workers). While many furloughed workers will eventually return to other corporate jobs, it is likely that others will follow in the footsteps of previous pink-slip recipients. Many workers who lost their jobs during corporate cutbacks either chose or were forced to pursue the entrepreneurial route rather than employment in the corporate arena. An Inc. 500 survey, a list of the 500 fastest-growing small companies, found that 40% of these founders started their businesses after a company reshuffling.29 The Council on Competiveness, an organization devoted to driving US competitiveness in world markets, explains, “Economic growth is not an orderly process of incremental improvements—it happens because new firms are created and older firms are destroyed. . . . And entrepreneurs are the moving force behind this churn that underpins the dynamism of the US economy.” Economist Joseph Schumpeter refers to this process as “creative destruction.” A result of this creative destruction is that employees are laid off as firms downsize or go out of business. This unemployment generates new entrepreneurial ventures.30 An example of an entrepreneur who chose to start his own business after being downsized was Patrick Kelly, who started a company called Physician Sales and Service, which rose to over $1.6 billion in revenue and became the nation’s largest supplier of medical supplies to physicians’ offices before it was purchased by the McKesson Corporation in 2013. When asked why he became an entrepreneur, Kelly said, “I didn’t choose to become an entrepreneur. I got fired and started a company in order to earn a living. I had to learn to be a CEO. I will tell you right now, I stole every idea I have. There is not an original thought in my head. I stole everything and you should too.” Another happy story regarding a downsized employee is the story of Bill Rasmussen, who was laid off from his public relations job. He went on to start the Entertainment Sports Programming Network (ESPN) in Connecticut, which is now jointly owned by Disney and the Hearst family and employs 6,500 people.

In 1970, only 16 American universities provided training in entrepreneurship. Today, more than 2,000 universities throughout the country (roughly two-thirds of all institutions) have at least one class, and many more classes are being taught in universities all over the world. In 1980, there were 18 entrepreneurship endowed chairs at business schools; that number of endowed chairs and professorships in entrepreneurship and related fields grew 71%, from 237 in 1999 to 406 in 2003.31,32 In fact, entrepreneurship has become an academic discipline in virtually all of the top business schools across the country. Another indicator of academia’s commitment to this field is the fact that business schools offer not only classes, but also minors and majors in the field of entrepreneurship. The number of entrepreneurship majors in undergraduate and MBA programs has risen; in the United States, there are approximately 200 colleges and universities that offer entrepreneurship studies, and over 1,000 MBA programs.33

Does entrepreneurial training work? While concrete research is difficult to gather and entrepreneurs such as Steve Jobs of Apple and Bill Gates of Microsoft have certainly succeeded without such education, a study by the University of Arizona showed that five years after graduation, the average annual income for entrepreneurship majors and MBAs who concentrated in entrepreneurship at school was 27% higher than that for students with other business majors and students with standard MBAs.34 In addition, according to a study by the Kauffman Foundation, 32% of successful entrepreneurs had taken at least five business classes, while only 18% of unsuccessful entrepreneurs had taken these kinds of courses. Anecdotal evidence is plentiful. Mark Cuban, who sold his start-up, Broadcast.com, to Yahoo! for $6 billion in 1999 and HDNet to Anthem Sports in 2019 and is the current owner of the Dallas Mavericks, swears by his entrepreneurship training. He notes, “One of the best classes I ever took was entrepreneurship in my freshman year at Indiana University. It really motivated me. There is so much more to starting a business than just understanding finance, accounting, and marketing. Teaching kids what has worked with startup companies and learning about experiences that others have had could really make a difference. I know it did for me.”35

Tatiana Saribekian, a Russian immigrant, believes that San Diego State University’s MBA program helped her master the art of the deal. After failing with her first US-based lumber venture, she decided to get an MBA, and concentrated in entrepreneurship. She has recently started over as a builder and reflects on her MBA in entrepreneurship: “My classes opened my eyes to how business works here in America. It is completely different from Russia. I think this time I will have a better chance at success.”36 Finally, the growth in entrepreneurship will be forever linked with America’s technological revolution, which began in the early 1980s. Companies such as Microsoft, Apple, Lotus, and Dell, to name a few, gave birth to the present technology industry, which is on pace to reach $5.2 trillion in 2020, according to the research consultancy IDC.37 Advances in technology have led to the proliferation of new products and services fostering the creation of companies in new areas, such as Internet-based businesses. The years 1995 and 1996 were heady times for Internet pioneers. This spur in entrepreneurial activity resulted in unprecedented job and wealth creation. For example, as of 2019 in Silicon Valley, there are over 2,000 tech companies, the densest concentration in the world.38

Traits of an Entrepreneur

Building a successful, sustainable business requires courage, patience, and resilience. It demands a level of commitment that few people are capable of making. Membership in the “entrepreneurs club,” while not exclusive, does seem to attract a certain type of individual. What, if any, are the common attributes of successful high-growth entrepreneurs? While it is impossible to identify traits that are common to all entrepreneurs, it is possible to describe certain characteristics that are exhibited by most successful entrepreneurs. A survey of 400 entrepreneurs undertaken by an executive development consultant, Richard Hagberg, identified the top characteristics that define entrepreneurs.39 These characteristics are:

1. Focused

2. Steadfast and undeviating

3. Positive outlook

4. Opinionated and judges quickly

5. Impatient

6. Prefers simple solutions

7. Autonomous and independent

8. Aggressive

9. Risk taker

10. Acts without deliberation and reactive

11. Emotionally aloof

While this list is thorough, the addition of a few more traits would make it more complete:

1. Opportunist

2. Sacrificer

3. Visionary

4. Problem solver

5. Comfortable with ambiguity or uncertainty

Some of these traits are worth discussing in more detail—focused, steadfast, and undeviating.

Successful entrepreneurs are focused on their mission and committed to getting it accomplished despite the enormous odds against them. They are tenacious in nature—they persevere. They are not quitters. If you want to join the club of entrepreneurship and you have never done anything to its completion in your life, this may not be the club for you, because it is one where you will be required to hang tough even when times get rough. And in all likelihood, especially in the first three to five years of a new business, there will be more bad times than good, no matter how successful the venture is. An example of an entrepreneur who was focused on her goals is Josephine Esther Mentzer, the founder of the Estée Lauder Cosmetic Company, who is described as a person who “simply out-worked everyone else in the cosmetics industry. She stalked the bosses of New York City department stores until she got some counter space at Saks Fifth Avenue in 1948.”40 Her company, which presently controls 8% of the cosmetics market in US department stores and had almost $12 billion in revenues in 2017 from 130 countries throughout the world, pioneered the practice, which is common today, of giving a free gift to customers with a purchase.

Positive Outlook and Optimistic

Entrepreneurs are confident optimists, especially when it comes to their ideas and their ability to successfully achieve their goals. They are people who view the future in a positive light, seeing obstacles as challenges to be overcome, not as stumbling blocks. They visualize themselves as owners of businesses, employers, and change agents. The rough-and-tumble world of entrepreneurship is not a good fit for someone who is not an optimist. Bryant Gumbel, the former Today show host and CBS morning show anchor, once told a story that illustrates this point well: It is Christmas morning and two kids—one a pessimist, the other an optimist—open their presents. The pessimist gets a brand new bike decked out with details and accessories in the latest style. “It looks great,” he says. “But it will probably break soon.” The second kid, an optimist and future entrepreneur, opens a huge package, finds it filled with horse manure, and jumps with glee, exclaiming, “There must be a pony in there somewhere!”41

Prefers Simple Solutions

Ross Perot, the founder of EDS, who recently died, and Ted Turner, the founder of CNN, are two successful entrepreneurs who had a prototypical knack for always describing the simplicity of their entrepreneurial endeavors. One of their favorite quotes, stated with their respective comforting southern accents, is, “It’s real simple.” One can easily envision one of them being the entrepreneur described in the following story of a chemist, a physicist, an engineer, and an entrepreneur. Each of them was asked how he or she would measure the height of a light tower with the use of a barometer. The chemist explained that she would measure the barometric pressure at the base of the tower and at the top of the tower. Because barometric pressure is related to altitude, she would determine the height of the tower from the difference in pressures. The physicist said that he would drop the barometer from the top of the tower and time how long it took to fall to the ground. From this time and the law of gravity, he could determine the tower’s height. The engineer said that she would lower the barometer from the top of the tower on a string and then measure the length of the string. Finally, the entrepreneur said that he would go to the keeper of the tower, who probably knows every detail about the tower, and say, “Look, if you tell me the height of the tower, I will give you this new shiny barometer.”42

Autonomous and Independent

Entrepreneurs are known to be primarily driven by the desire to be independent of bosses and bureaucratic rules. Essentially, they march to their own beat. As one observer who was experienced in training entrepreneurs noted, “Entrepreneurs don’t march left, right, left. They march left, left, right, right, left, hop, and skip.”43

Risk Taker

A study by Wayne Stewart, a management professor at Clemson University, investigated common traits among serial entrepreneurs, whom he defined as people owning and operating three or more businesses over their lifetime. He found that the 12% of all entrepreneurs who fit the “serial entrepreneur” bill had a higher propensity for risk, innovation, and achievement than their counterparts. In essence, they were less scared of failure.44 The most common misconception people have of entrepreneurs is that they are blind risk takers. Most people think that entrepreneurs are no more than wild gamblers who start businesses with the same attitude and preparation that they would undertake if they were going to Las Vegas to roll the dice, hoping for something positive to happen. This perception could not be further from the truth. Successful entrepreneurs are, without doubt, risk takers—they have to be if they are going to seize upon new opportunities and act decisively in ambiguous situations—but for the most part, they are “educated” risk takers. They weigh the opportunity and its associated risks before they take action. They research the market or business opportunity, prepare solid business plans prior to taking action, and afterward diligently “work” the plan. They also recognize that risk taking does not—despite the fact that this is a calculated risk—always guarantee success. There are always exceptions to the rule, however. Fred Smith, the founder and CEO of FedEx, did roll the dice, so to speak, when his start-up was low on capital. Despondent after being unsuccessful at raising capital during a trip to Chicago, he boarded a plane to Las Vegas at O’Hare Airport instead of to his home in Memphis and played blackjack, winning $30,000, which he used to save his company. Entrepreneurs are risk takers because failure does not scare them. As John Henry Peterman, the founder of the Kentucky-based J. Peterman Company, said, “There is a great fear of failure in most people. I never had that. If failing at something destroys you, then you really have failed. But if failing leads you to a new understanding, new knowledge, you have not. If you don’t make any mistakes, you’re not doing it right.”45

Opportunist

Entrepreneurs are proactive by nature. The difference between an entrepreneur and a non-entrepreneur is that the former does not hesitate to seize upon opportunities. When entrepreneurs see an opportunity, they execute a plan to take advantage of it. That disposition is in stark contrast to non-entrepreneurs, who may see something glittering at the bottom of a stream and say, “Isn’t that gold?” Instead of stopping and mining the gold, they simply keep paddling their boat.46 An example of this type of opportunism is the story of Eugene Qahhaar, who owned a hot dog stand on the South Side of Chicago in the early 1970s. During one of the hottest days of August 1973, a refrigerated truck filled with frozen fish broke down in front of Henry’s stand. Rather than let the fish spoil, Henry, who had never sold fish before, offered to buy the entire stock at a very sharp discount. The truck driver agreed, and that is how Dock’s Great Fish Restaurant began. Henry named the restaurants after his father, Dock. There are presently 27 Dock’s restaurants in Chicago and Cleveland.

Sacrificer

Every successful entrepreneur will acknowledge that success does not come without sacrifice. The most common sacrifice that an entrepreneur makes is in terms of personal income, particularly during the initial stages of a company. Almost all entrepreneurs must be willing to give up some amount of personal income to get a business started, either by committing their own resources or by taking a cut in pay. One of Jeff Bezos’s early investors said that the most convincing factor was that Bezos had given up a job at D. E. Shaw with a seven-figure annual salary to start Amazon.com. The investor quoted, “The fact that Bezos had left that kind of situation overwhelmed me. It gave me a very, very powerful urge to get involved with this guy.”47 In fact, capital providers, such as bankers and venture capitalists, want to see an entrepreneur earning a salary that is enough to live comfortably, but not too comfortably, during the buildup stage of the business. Specifically, the entrepreneur’s expected salary should be enough to cover her personal bills (home mortgage, car payment, and so on), but not enough to permit personal savings of any significant magnitude. This indicates to potential financial backers both the entrepreneur’s level of commitment to the venture and her realism about the challenges that lie ahead. A case in point: a venture capitalist received a business plan from a team of three prospective entrepreneurs who wanted to start a national daily newspaper targeting middle-class minorities. The idea seemed sound—such a newspaper did not exist to meet the demands of a rapidly growing segment of the US population. The request for start-up capital was rejected, however, as it was evident to the venture capitalist, upon reading the business plan, that the team did not understand this key notion of sacrificing personal income. The three of them included in their projections starting salaries of nearly $400,000 each, comparable to the corporate salaries they were earning at the time! Such salaries put them in the top 1% of the highest-salaried people in the country. The venture capitalist viewed this as a sure sign that these three businesspeople were not sincere entrepreneurs.

Another difficult sacrifice that successful entrepreneurs sometimes make is spending less time with their families. For example, entrepreneur Alan Robbins, the owner of a 50-employee firm called Plastic Lumber Company, once said that he regretted not spending more time with his children during the beginning of his business, but he considered it a trade-off he had to make. He argued, “When you start a business like this . . . you have to deny your family a certain level of attention.”48 The demands of owning or building a business put considerable strains on an entrepreneur’s time. However, this does not mean that the entrepreneur must completely neglect his family or friends in order to run a successful business. To do so in the name of entrepreneurship is called “entremanureship”! When I owned my businesses, I did not miss the nightly dinner with my family. I did not miss my kids’ birthday parties or baseball games—I worked around them. My two daughters are adults now, but when I started my businesses they were ages eight and four. I coached my younger daughter’s Little League baseball team and her flag football team. I would have coached the older one, too, but she had decided that perhaps it would be best for me to simply cheer from the stands. I have seen more of my kids’ games and events than any other parent I know. Of course you are going to work long hours in the first couple of years to get your business going. But one of the beautiful things about being your own boss is that, by and large, you are the one who determines which hours to work. In addition to sitting on several boards of billion-dollar companies, I am also a director for several start-ups. I tell these entrepreneurs, “Go home, have dinner with the family, and read the kids a bedtime story. Then get your butt back to work.” When Staples surveyed small-business owners (those with under 20 employees), 33% reported working while they eat dinner, 73% said that they worked during their last vacation, and over 75% reported working more than a 40-hour workweek.49 The MasterCard Global Business Survey of 4,000 small-business owners found that the average US business manager works 52 hours per week. This figure actually rises to 54 hours per week if you include all eight countries surveyed.50 When Inc. magazine surveyed the CEOs of its 500 fastest-growing companies, 66% of them remember working at least 70 hours per week when they started their company, and 40% reported working more than 80 hours per week.51 Ken Ryan, CEO of Airmax, told Inc., “There were times when I slept on the floor by the phone so as not to miss a call.” The good news is that only 13% say that they now log more than 70 hours. Trust me, it gets better. You can make time to take your kids to the park, but nobody said starting a business was a walk in one.

Visionary

Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary defines a visionary as someone who is “marked by foresight.” This is an appropriate characterization of most successful entrepreneurs. They are able to anticipate future trends, identify opportunities, and visualize the actions needed to accomplish a desired goal. They must then sell this vision to potential customers, financiers, and employees. A couple of entrepreneurs who were great visionaries and made an impact on almost everyone’s daily lives include Ray Kroc, founder of McDonald’s Corporation. Ray Kroc was an acquirer; he purchased McDonald’s restaurants in 1961 for $2.7 million from the two brothers who founded the chain, Dick and Mac McDonald. After concluding that Americans were becoming people who increasingly liked to “eat and run” rather than dining traditionally at a restaurant or eating at home, his vision was to build the quick service, limited-menu restaurants throughout the country. McDonald’s, with operations in 119 countries, is now the largest restaurant company in the world with almost 35,000 restaurants. By the way, for the graying dreamers reading this book, Kroc was a 52-year-old sales clerk when he bought McDonald’s.

Another visionary was Akio Morita, cofounder of Sony Corporation. The company, which was started in 1942 under the name Tokyo Telecommunications Engineering Inc. and went on to become the first Japanese firm on the NYSE in 1970, succeeded by using Akio’s vision to market the company throughout the world so that the name would immediately communicate high product quality. While this is a marketing concept that is commonly used today, it was not so 40 years ago, especially in Japan. In fact, most Japanese manufacturers produced products under somebody else’s name, including Pentax for Honeywell, Ricoh for Savin, and Sanyo for Sears. Sony successfully introduced the pocket-sized transistor radio in 1957. Six years later, in 1963, with the vision of making Sony an international company, Morita moved his entire family to New York so that he could personally get to know the interests, needs, and culture of Americans and the American market.52 All successful entrepreneurs are visionaries at one time or another. They have to constantly reinvent their strategy, look for new opportunities, and go after new products and new ideas if they are to survive. However, this does not mean that they have this ability all the time. Visionaries can become non-visionaries. In fact, as Cognetics Consulting points out, sometimes “the most astute masters of the present are often the least able to see the future.”53 Examples of quotes from some famous non-visionaries include:

“Heavier than air flying machines are impossible.”

—Lord Kelvin, President of the Royal Society, in 189554

“Everything that can be invented has been invented.”

—Charles H. Duell, Commissioner, US Office of Patents, in 189955

“I think there is a world market for maybe five computers.”

—Thomas Watson, Chairman, IBM, in 194356

“We don’t like their music, we don’t like their sound, and guitar music is on the way out.”

—Decca Recording Company, rejecting the Beatles in 196257

“There is no reason anyone would want a computer in their home.”

—Ken Olsen, Founder and Chairman, Digital Equipment Corp., in 197758

Problem Solver

Anyone working in today’s competitive and ever-changing business environment knows that the survival of a company, be it large or small, depends on its ability to quickly identify problems and find solutions. Successful entrepreneurs are comfortable with and adept at identifying and solving problems facing their businesses. Risk takers by nature, they are willing to try new ways to solve the problems facing their companies and are capable of learning from their own and others’ mistakes or failures. The successful entrepreneur is one who says, “I failed here, but this is what I learned.” Successful entrepreneurs are always capable of extracting some positive lesson from any experience. An example of someone who exhibits this characteristic is Norm Brodsky, a former owner of six companies and presently a writer for Inc. magazine. In an article, he says, “I prefer chaos. Deep down I like having problems. It is hard to admit it, but I enjoy the excitement of working in a crisis atmosphere. That is one of the reasons I get so much pleasure out of starting businesses. You have nothing but problems when you are starting out.”59

Comfortable with Ambiguity or Uncertainty

The ability to function in an environment of continual uncertainty is a common trait found among successful entrepreneurs. Often, they will be required to make decisions, such as determining market demand for a newly developed product or service, without having adequate or complete information. Other important traits that successful entrepreneurs have in common are that they are hardworking people who possess numerous skills, as they are required to play multiple roles as owners of businesses. They are good leaders. They have the ability to sell, whether it is a product, an idea, or a vision. One of the most infamous sales pitches used by an entrepreneur was when Steven Jobs, the cofounder of Apple Computer, was closing his recruiting speech to PepsiCo.’s John Sculley, whom he wanted to become Apple’s CEO. To sell John on the opportunity, Jobs asked him, “Do you want to spend the rest of your life selling sugared water, or do you want a chance to change the world?”60

Impact on the Economy

Entrepreneurs with small and medium-sized growth businesses are playing an increasingly crucial role in the success of the US economy.61 Not only are they providing economic opportunities to a diverse segment of the population, but they are also providing employment to an increasingly large segment of the US population. The Fortune 500 companies are no longer the major source of employment; rather, entrepreneurs are creating jobs and therefore are doing “good for society by doing well.” As one employee of a 400-employee firm said about his company’s owner, “To everybody else she’s an entrepreneur. But to me she is a Godsend.”62 In the 1960s, 1 out of every 4 persons in the United States worked for a Fortune 500 company. Today, only 1 out of every 14 people works for one of these companies. Contrary to popular belief, small businesses are not the exception in the American economy; they are the norm. This fact was highlighted when Crain’s Chicago Business weekly business newspaper advertised its new small-business publication by taking out a full-page advertisement that read: “There Was a Time When 90% of Chicago Area Businesses Had Revenues of Under $5 Million. (Yesterday).”63 On the national level, the same holds true. Out of the approximately 24.8 million businesses in the United States, only about 9% have annual revenues greater than $1 million.64

Impact on Gender and Race

The entrepreneurial phenomenon has been widespread and inclusive, affecting both genders and all races and nationalities in the United States. One group that has benefited is female entrepreneurs. In the 1960s, there were fewer than 1 million women-owned businesses employing less than 1 million people. By the 1970s, women owned less than 5% of all businesses in the United States. In the 1980s, they owned about 3 million businesses, approximately 20% of all businesses, generating $40 billion in annual revenues. Things have changed tremendously. In 2017, there were 11.6 million women-owned businesses in the United States who employed 9 million people, and generated $1.7 trillion in revenues. Finally, not surprisingly, contrary to much of what is said in the popular press, women are not starting businesses out of need. Forte Foundation research reports that women start businesses for the same reasons as men: because they are driven to achieve and want control over their achievement.65 The entrepreneurship revolution has also included virtually all of the country’s minority groups. In 2017, there were 11 million firms owned by minorities, generating $1.8 trillion in revenue and employing 6 million people.66

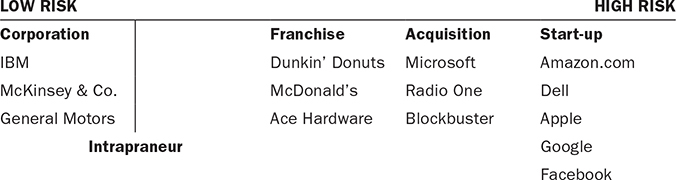

The Entrepreneurial Spectrum

When most people think of the term entrepreneur, they envision someone who starts a company from scratch. This is a major misconception. As the entrepreneurial spectrum in Figure 2-1 shows, the tent of entrepreneurship is broader and more inclusive. It includes not only those who start companies from scratch (start-up entrepreneurs), but also those people who acquire an established company through inheritance or a buyout (acquirers). The entrepreneurship tent also includes franchisors and franchisees. Finally, it also includes intrapreneurs, or corporate entrepreneurs. These are people who are gainfully employed at a Fortune 500 company and are proactively engaged in entrepreneurial activities in that setting. Chapter 12 is devoted to the topic of intrapreneurship. But be it via acquisition or start-up, each entrepreneurial process involves differing levels of business risk, as highlighted in Figure 2-1.

FIGURE 2-1 The Entrepreneurial Spectrum

Corporations

While the major Fortune 500 corporations, such as IBM, are not entrepreneurial ventures, IBM and others are included on the spectrum simply as a business point of reference. Until the early 1980s, IBM epitomized corporate America: a huge, bureaucratic, and conservative multibillion-dollar company where employees were practically guaranteed lifetime employment. Although IBM became less conservative under the leadership of Louis Gerstner, the company’s first non-IBM-trained CEO, it has always represented the antithesis of entrepreneurship, with its “Hail to IBM” corporate anthem, white shirts, dark suits, and policies forbidding smoking and drinking on the job and strongly discouraging them off the job.67 In addition to the IBM profile, another great example of the antithesis of entrepreneurship was a statement made by a good friend, Lyle Logan, an executive at Northern Trust Corporation, a Fortune 500 company, who proudly said, “Steve, I have never attempted to pass myself off as an entrepreneur. I do not have a single entrepreneurial bone in my body. I am very happy as a corporate executive.” As can be seen, the business risk associated with an established company like IBM is low. Such companies have a long history of profitable success and, more important, have extremely large cash reserves on hand.

Franchises

Franchising employs more than 7.6 million people and accounts for roughly $674 billion in economic output.68 Like a big, sturdy tree that continues to grow branches, a well-run franchise can spawn hundreds of entrepreneurs. The founder of a franchise—the franchisor—is a start-up entrepreneur, such as Bill Rosenberg, who founded Dunkin’ Donuts in 1950 and now has approximately 10,500 stores in 32 countries.69 These guys sell enough donuts in a year to circle the globe . . . twice! Rosenberg’s franchisees (more than 7,000 in the United States alone70), who own and operate individual franchises, are also entrepreneurs. They take risks, operate their businesses expecting to gain a profit, and, like other entrepreneurs, can have cash flow problems. The country’s first franchisees were a network of salesmen who in the 1850s paid the Singer Sewing Machine Company for the right to sell the newly patented machine in different regions of the country. The franchise system ultimately became popular, and franchisees began operating in the auto, oil, and food industries. Today, it’s estimated that a new franchise outlet opens somewhere in the United States every eight minutes.71

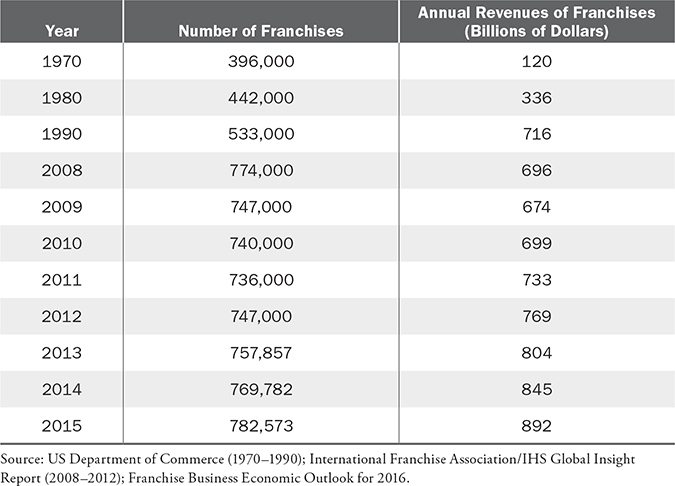

Franchisees are business owners who put their capital at risk and can go out of business if they do not generate enough profits to remain solvent.72 By one estimate, there are at least 733,000 individual franchise business units in America,73 of which 10,000 are home-based. The average initial investment in a franchise, not including real estate, is between $350,000 and $400,000.74 Additional data from the International Franchise Association, given in Table 2-2 (see next page), show that the number of franchised establishments grew from 1970 to a peak of 782,573 in 2015.

TABLE 2-2 Growth in Franchises in the United States (Selected Years)

Because a franchise is typically a turnkey operation, its business risk is significantly lower than that of a start-up. The success rate of franchisees is between 80 and 97%, according to research by Arthur Andersen and Co., which found that only 3% of franchises had gone out of business five years after starting their business. Another study undertaken by Arthur Andersen found that of all franchises opened between 1987 and 1997, 85% were still operated by their original owner, 11% had new owners, and 4% had closed. The International Franchise Association reports that 70% of franchisors charge an initial fee of $40,000 or less.75

Max Cooper is one of the largest McDonald’s franchisees in North America, with 45 restaurants in Alabama. He stated his reasoning for becoming a franchisee entrepreneur as follows:

You buy into a franchise because it is successful. The basics have been developed and you are buying the reputation. As with any company, to be a success in franchising, you have to have that burning desire. If you do not have it, do not do it. It is not easy.76

Acquisitions

An acquirer is an entrepreneur who inherits or buys an existing business. This list includes Howard Schultz, who acquired Starbucks Coffee in 1987 for approximately $4 million when it had only six stores. Today, more than 40 million customers a week line up for their cafe mochas, cappuccinos, and caramel macchiato in 29,324 Starbucks locations in 60 countries. Annual revenues top $24.7 billion.77

Another successful entrepreneur who falls into the category of acquirer is Cathy Hughes, who over the past 32 years has purchased 71 radio stations and divested 17. Cathy is one of the few African Americans and women to ever take a company public. Her company, Radio One, trades on the New York Stock Exchange as UONE. In 2019, it generated over $425 million in revenue and a whooping $125 million in EBITDA!78

One of the most prominent entrepreneurs who falls into this category is Wayne Huizenga, Inc. magazine’s 1996 Entrepreneur of the Year and Ernst & Young’s 2005 World Entrepreneur of the Year. His reputation as a great entrepreneur came partially from the fact that he was one of the few people in the United States to have ever owned three multibillion-dollar businesses. Like Richard Dreyfuss’s character in the movie Down and Out in Beverly Hills, a millionaire who owned a clothes hanger–manufacturing company, Wayne Huizenga was living proof that an entrepreneur does not have to be in a glamorous industry to be successful. His success came from buying businesses in the low- or no-tech, unglamorous industries of garbage, burglar alarms, videos, sports, hotels, and used cars.

Huizenga never started a business from scratch. His strategy was to dominate an industry by buying as many of the companies in the industry as he could as quickly as possible and consolidating them. This strategy is known as the “roll-up,” “platform,” or “poof” strategy—starting and growing a company through industry consolidation. (While the term roll-up is self-explanatory, the other two terms may need brief explanations. The term platform comes from the act of buying a large company in an industry to serve as the platform for adding other companies. The term poof comes from the idea that as an acquirer, one day the entrepreneur has no businesses and the next, “poof”—like magic—she purchases a company and is in business. Then “poof” again, and the company grows exponentially via additional acquisitions.) As Jim Blosser, one of Huizenga’s executives, noted, “Wayne doesn’t like start-ups. Let someone else do the R&D. He’d prefer to pay a little more for a concept that has demonstrated some success and may just need help in capital and management.”79

Huizenga’s entrepreneurial career began in 1961 when he purchased his first company, Southern Sanitation Company, in Florida. The company’s assets were a garbage truck and a $500-a-month truck route, which he worked personally, rising at 2:30 a.m. every day. This company ultimately became the multibillion-dollar Waste Management Inc., which Huizenga had grown nationally through aggressive acquisitions. In one nine-month period, Waste Management bought 100 smaller companies across the country. In 10 years, the company grew from $5 million a year to annual profits of $106.5 million on nearly $1 billion in revenues. In four more years, revenue doubled again.80

Huizenga then exited this business and went into the video rental business by purchasing the entire Blockbuster Video franchise for $32 million in 1984, after having been unable to purchase the Blockbuster franchise for the state of Florida because the state’s territorial rights had already been sold to other entrepreneurs before Huizenga made his offer. When he acquired Blockbuster Video, it had 8 corporate and 11 franchise stores nationally. The franchisor was generating $7 million annually through direct rentals from the 8 stores, plus franchise fees and royalties from the 11 franchised stores.81 Under Huizenga, who did not even own a VCR at the time, Blockbuster flourished. For the next seven years, through internal growth and acquisitions, Blockbuster averaged a new store opening every 17 hours, resulting in its becoming larger than its next 550 competitors combined. Over this period of time, the price of its stock increased 4,100%; someone who had invested $25,000 in Blockbuster stock in 1984 would have found that seven years later, that investment would be worth $1.1 million, and an investment of $1 million in 1984 would have turned into $41 million during this time period. In January 1994, Huizenga sold Blockbuster Video, which had grown to 4,300 stores in 23 countries, to Viacom for $8.5 billion. In 2010, Blockbuster Video went bankrupt, filing Chapter 11. Today, there is only one Blockbuster store in the world: Bend, Oregon.

Huizenga pursued the same roll-up strategy in the auto business by rapidly buying as many dealerships as he possibly could and bundling them together under the AutoNation brand. By the way, if you ever found yourself behind the wheel of a National or Alamo rental car, you were also driving one of Huizenga’s vehicles—both companies were among his holdings. What Huizenga eventually hoped to do was to have an entire life cycle for a car. In other words, he would cars from the manufacturer, sell some of them as new, lease or rent the balance, and later sell the rented cars as used.

In 2015, Huizenga sold the US operations of Swisher, a service to clean bathrooms at restaurants and shops, to hygiene firm Ecolab for $40 million. Huizenga also owned or previously owned practically every professional sports franchise in Florida, including the National Football League’s Miami Dolphins, the National Hockey League’s Florida Panthers, and Major League Baseball’s Florida Marlins. Mr. Huizenga passed away in March 2018 with an estimated net worth of $2.5 billion.82

Now, here is your bonus points question—the one I always ask my MBA students. What is the common theme among all of Huizenga’s various businesses—videos, waste, sports, and automobiles? Each one of them involves the rental of products, generating significant, predictable, and, perhaps most important, recurring revenues. The video business rented the same video over and over again, and the car rental business rents the same car a multitude of times. In waste management, he rented the trash containers. But what is being rented in the sports business? He rented the seats in the stadiums and arenas that he owned. Other businesses that are in the seat rental business are airlines, movie theaters, public transportation, and universities!

Another example of an acquirer is Bill Gates, the founder of Microsoft. The company’s initial success came from an operating system called MS-DOS, which was originally owned by a company called Seattle Computer Products. In 1980, IBM was looking for an operating system. After hearing about Bill Gates, who had dropped out of Harvard to start Microsoft in 1975 with his friend Paul Allen, the IBM representatives went to Albuquerque, New Mexico, where Gates and Allen were, to see if Gates could provide them with the operating system they needed. At the time, Microsoft’s product was a version of the programming language BASIC for the Altair 8800, arguably the world’s first personal computer. BASIC had been invented in 1964 by John Kenney and Thomas Kurtz.83 As he did not have an operating system, Gates recommended that IBM contact another company called Digital Research. Gary Kildall, the owner of Digital Research, was absent when the IBM representatives visited, and his staff refused to sign a nondisclosure statement with IBM without his consent, so the representatives went back to Gates to see if he could recommend someone else. True opportunistic entrepreneur that he is, Gates told them that he had an operating system to provide to them and finalized a deal with IBM. Once he had done so, he went out and bought the operating system, Q-DOS, from Seattle Computer Products for $50,000 and customized it for IBM’s first PC, which was introduced in August 1981. The rest is entrepreneurial history. So Bill Gates, one of the world’s wealthiest people, with a personal net worth in excess of $96 billion,84 achieved his initial entrepreneurial success as an acquirer and has now become a great philanthropist with his wife, Melinda.

Microsoft continues to grow, investing billions of dollars to acquire 130 technologies and companies since 1994.85 In June 2012, Microsoft paid $1.2 billion in cash for Yammer, an enterprise social network system,86 and in May 2011, it invested $8.5 billion in cash for the ubiquitous online service Skype, a global digital connection platform for voice and visual communications. There is still plenty of “dry powder,” too, since Microsoft recorded $11.0 billion in cash on its books by its fiscal year end of June 2018.87 In October 2018, Microsoft completed the $7.5 billion acquisition of GitHub, a software development platform.88

Start-Ups

Creating a company from nothing other than an idea for a product or service is the most difficult and risky way to be a successful entrepreneur. Two great examples of start-up entrepreneurs are Steve Wozniak, a college dropout, and Steve Jobs of Apple Computer. As an engineer at Hewlett-Packard, Wozniak approached the company with an idea for a small personal computer. The company did not take him seriously and rejected his idea; this decision turned out to be one of the greatest intrapreneurial blunders in history. With $1,300 of his own money, Wozniak and his friend Steve Jobs launched Apple Computer from his parents’ garage.

The Apple Computer start-up is a great example of a start-up that was successful because of the revolutionary technological innovation created by the technology genius Wozniak. Other entrepreneurial firms that were successful as a result of technological innovations include Amazon.com, founded by Jeff Bezos; Google, with Larry Page and Sergey Brin; and Facebook, with Mark Zuckerberg.

Entrepreneurial start-ups have not been limited to technology companies. In 1993, Kate Spade quit her job as the accessories editor for Mademoiselle and, with her husband, Andy, started her own women’s handbag company called Kate Spade, Inc. Her bags, a combination of whimsy and function, have scored big returns on the initial $35,000 investment from Andy’s 401(k). In 1999, sales had reached $50 million. Neiman Marcus purchased a 56% stake in February 1999, for $33.6 million.89 In 2017, Coach Inc. acquired Kate Spade for $2.4 billion.90

Finally, there are also numerous successful start-ups that began from an idea other than the entrepreneur’s. For example, Mario and Cheryl Tricoci are the owners of a $40 million international day spa company headquartered in Chicago called Mario Tricoci. In 1986, after returning from a vacation at a premier spa outside the United States, they noticed that there were virtually no day spas in the country, only those with weeklong stay requirements. Therefore, they started their day spa company, based on the ideas and styles that they had seen during their international travels.91

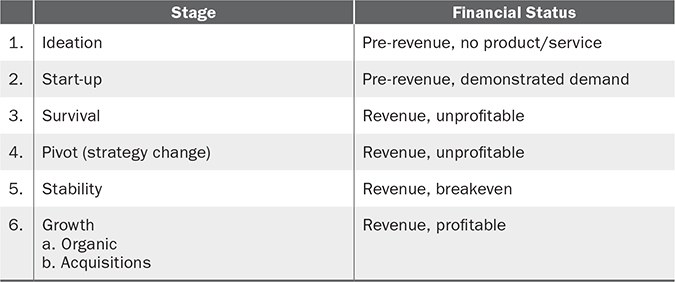

Stages of Entrepreneurship

It has been said many times that “overnight success” for the successful entrepreneur will usually take 7 to 10 years. During that time, the entrepreneur will proceed through the stages of Entrepreneurship shown in Table 2-3.

TABLE 2-3 Stages of Entrepreneurship

The movement from one stage to another stage may or may not be linear, from Stage 1 to Stage 2 to Stage 3. Some entrepreneurs may jump from Stage 2 to Stage 4, or Stage 3 to Stage 5. Almost all entrepreneurs will experience the Stage 3 category of survival. Some will experience it shortly after start-up, others may never get beyond the survival stage, and those who do get to the stability and/or growth stages may digress back to the survival stage, experiencing it multiple times.

It is imperative for financing purposes that the entrepreneur clearly knows the entrepreneurship stage of his company. The wise entrepreneur pursues capital from investors who target specific stages. For example, it would be foolish for an entrepreneur in the growth stage to try to raise money from an investor who invests in early stage start-ups.

Entrepreneurial Finance

In a recent survey of business owners, the functional area they cited as being the one in which they had the weakest skill was the area of financial management—accounting, bookkeeping, the raising of capital, and the daily management of cash flow. Interestingly, these business owners also indicated that they spent most of their time on finance-related activities. Unfortunately, the findings of this survey are an accurate portrayal of most entrepreneurs—they are comfortable with the day-to-day operation of their businesses and with the marketing and sales of their products or services, but they are very uncomfortable with the financial management of their companies. Entrepreneurs cannot afford this discomfort. They must realize that financial management is not as difficult as it is made out to be. It must be used and embraced because it is one of the key factors for entrepreneurial success.

Prospective and existing “high-growth” entrepreneurs who currently are not financial managers will appreciate this book. Its objective is to be a user-friendly guide that will provide entrepreneurs with an understanding of the fundamentals of financial management and analysis that will enable them to better manage the financial resources of their business and create economic value. Entrepreneurial finance is distinct from corporate finance; it is more integrative, including the analysis of qualitative issues such as marketing, sales, personnel management, and strategic planning. The questions that are answered in this book include:

• What financial tools can be used to manage the cash flow of the business efficiently?

• Why is valuation important?

• What is the value of the company?

• Finally, how, where, and when can financial resources be acquired to finance the business?