We all think we know what stress is and that we can easily recognise its symptoms. It seems that stress has become more common in today’s society and there is a risk that familiarity will breed contempt for it. But the long-term effects of stress are worthy of far greater respect: stress can destroy lives and families.

This chapter sets out to ensure that you can recognise the signs of stress in yourself, so that you can take it seriously. It will examine the science behind stress: the way our bodies are designed to respond, and attempts to predict stress in people. This will lead us to a formal understanding of what stress is, which will be the basis for learning how to control it – and controlling stress is the basis of this book.

Signs of stress

The earliest symptoms of stress are often subtle. A bit of anxiety, feeling a little blue, getting easily flustered and angry, and tiredness are all early warnings. You may also notice changes in yourself and in your behaviour. Let’s look at some of the common signs of stress.

Emotional signs of stress

As we get stressed, our levels of anxiety can cause us to respond less appropriately to unexpected and unwanted events. Do you sometimes find yourself overly defensive or aggressive – sometimes even looking for arguments? Do you feel detached from life, wanting to withdraw? Maybe your confidence has dropped noticeably and you find yourself feeling guilty or inadequate about every little failing.

Physical and mental signs of stress

One of the first features of stress is often poor or irregular sleep patterns, leaving you constantly tired (and anxious at bedtime). You also start to get every little bug going around, leading to a feeling of a constant cold with runny nose and sore throat. Other signs of diminishing health are skin problems and cold sores. Your digestion seems a little unreliable, leading to diarrhoea or constipation, and maybe you get more headaches than you used to. Back and neck pain can often follow and all of this leads to poor concentration and panic at not getting things done or not being able to cope. There are a host of other signs too, like an uncontrollable little twitch in one eye and a drop in your libido.

Important note: Some of these symptoms could also be signs of illness. If you are in any doubt, contact your general practitioner.

Behavioural signs of stress

A rush-rush busy-busy lifestyle is not just a trigger, but a symptom of stress, which leads to working longer and longer hours. This leaves you less time to relax and take care of yourself, so your appearance can start to suffer, as will your diet. More fast food, sugary or caffeine drinks, chocolate, nicotine and alcohol all indicate that you are trying to cope with stress; maybe you have lost your appetite or, paradoxically, find yourself overeating. You may also notice yourself becoming more irritable and argumentative as your patience is tried more and more. Impatience leads to a short temper, forgetfulness and more mistakes and accidents. You are becoming a danger to yourself and others.

Assess your symptoms. Count how many of each type of symptom you have on a regular or long-term basis.

Emotions

- Anxiety

- Tearfulness

- Aggressiveness

- Withdrawal

- Guilt

- Inadequacy

Physical symptoms

- Dodgy tummy

- Headaches

- Back, neck or shoulder pain

- Poor sleep

- Constant illnesses

- Loss of sex drive

Changes in your behaviour

- Working long hours

- Bad diet

- Argumentative and short-tempered

- Forgetful

- Less attention to your appearance and self-care

- Making mistakes

Physiology of stress

There was a time when your ancient ancestors lived in a ruthless environment, long before the brilliant series of books appeared. Every day a lion, or a bear, or something even bigger and uglier woke up and it knew that, if it did not catch some tasty morsel, it would go to sleep hungry. And at the same time, every morning, when your ancestors woke up, they knew that, if they did not keep out of the jaws of all those creatures, they would never go to sleep again.

The good news is that your ancestors did all survive … at least long enough to have healthy children. The bad news is that those children – and you in your turn – have inherited a fight-or-flight response, which is poorly designed for life in the twenty-first century. Whenever your brain detects stress, it responds in just the same way as your ancestors’. Somewhere between 20 and 30 different stress hormones are released into your bloodstream and, together, they have a massive impact on you. Your natural response to stress comes from the effect of these hormones.

Your senses become more acute, your breathing becomes faster and shallower, your pulse rate shoots up, and your muscles get tense, ready to spring into action. You sweat, you become anxious, you want to run away!

And at the same time as this part of your nervous system – called your sympathetic nervous system – jumps into overload, your body shuts down the other part of your nervous system, which is responsible for immunity, repair, digestion, sleep regulation and sexual function.

So, as if it isn’t bad enough that when we are stressed we tense up, we sweat and our hearts race, but we also lose our appetite, can’t sleep, get spots and lose our sex drive!

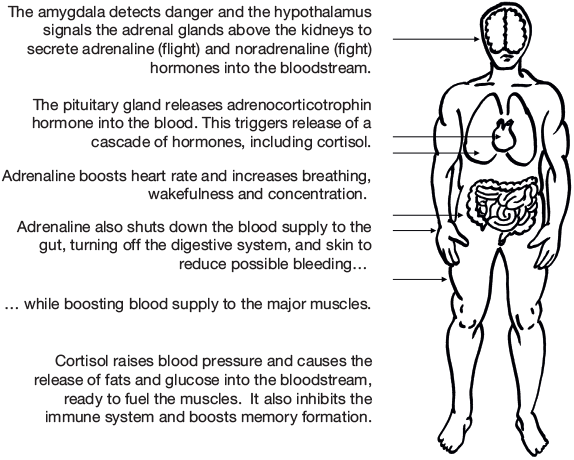

Figure 1.1 illustrates the main elements of our physiological response to stress.

All of these changes have positive short-term effects that allow us to cope with a sudden threat, but adverse long-term effects that, if they persist, will do you the harm that we recognise as the symptoms of stress. Part of brilliant stress control and management is finding time to let the stress hormones discharge fully, before the next onslaught.

The good news for managing immediate threats

Your sympathetic nervous system jumps into overload:

- Your senses get more acute and you become more alert.

- Your breathing and heart rates increase, bringing more oxygen to your muscles.

- Your muscles get ready for action.

- You will notice increased sweating, to keep your muscles cool.

- Your blood thickens, ready to clot more easily, if you are hurt.

- Your hunger is suppressed, so you can focus on the threat at hand.

The bad news for your long-term health

Your parasympathetic nervous system shuts down:

- Your immune system is suppressed.

- Digestion stops.

- Your sleep is inhibited.

- You experience a depressed libido.

- Your heart is under increased pressure.

Type A and Type B

In the 1950s, heart specialists Dr Meyer (Mike) Friedman and Dr Ray Rosenman observed that a majority of their patients had a consistent set of personality and behaviour traits, which led them to dub such people as Type A personalities. In contrast to others (Type B personalities), they argued that Type As had an increased risk of heart disease. Their original research was first published in an academic journal in 1959 and their subsequent 1974 book, Type A Behaviour and your Heart, became a best-seller.

Are you a Type A or a Type B?

Score yourself on a scale of 0 to 6. Score low numbers according to how like the statements on the left you are, and high numbers if you are more like the corresponding statement on the right.

What are Types A and B?

Type A behaviours include a sense of urgency and a need to get as much done as possible. In the car park of Friedman’s and Rosenman’s clinic, all the visitors would typically back their cars into parking spaces to allow a quick getaway. Patients of other clinics parked more randomly. Type As are competitive, impatient and often hostile.

Friedman and Rosenman concluded that by spotting Type A behaviour they could predict heart disease.

How significant are Types A and B?

The good news is that further studies have shown that Type A behaviour, as Friedman and Rosenman defined it, is not a reliable predictor of heart disease – phew. But one aspect of it is: hostility. In numerous studies, general hostility is associated with increased mortality from heart disease and, indeed, a number of other diseases.

How this happens is not clear, and some evidence is contradictory.

For example, some experiments suggest that expressing anger heightens the link to heart disease and others suggest that suppression is more significant. What is clear is that, when we suppress our emotions, our bodies increase the physiological changes they cause.

Since provocation causes our bodies to release the fight (noradrenaline) and flight (adrenaline) hormones, suppressing our emotions can increase our hormonal response. Over a long period, this will lead to increased stress.

Type T

Adrenaline is the hormone responsible for the ‘rush’ of increased heart rate and oxygen flow we get when we feel under threat – whether from an unwanted source or when we seek out our thrills. However, different people feel that rush with less or more provocation. Dr David McCobb is a biologist specialising in the brain at Cornell University. He has found evidence of two different versions of a protein that is fundamental to the rate of release of adrenaline.

Anxiety is related to an increase in one form of the protein, leading to the ready release of adrenaline under low levels of threat. On the other hand, the second form of the protein dampens adrenaline release, meaning that it takes more provocation to get the same physiological response.

This provides the first hint of an explanation of why some people don’t just cope well under pressure: they seek it out. Psychologist Frank Farley refers to these people as Type T where the T stands for Thrill. Type Ts like extreme sports and risk taking, and appear remarkably calm in situations that would rattle the rest of us.

Stress or strain?

Stress is an external stimulus. It’s all of the day-to-day, week-to-week problems and difficulties we have to face; it’s the angry boss, the aggressive driver, the rude shop assistant, the pressing deadline, the stupid helpdesk and the queue that never moves in the supermarket. It’s the endless list of things we have to do.

We all have this in our lives, so why is it that some people let themselves get really stressed and uptight and frustrated and angry; and then make themselves really ill? At the same time, others seem to take it all in their stride; they’re cool, they’re relaxed, they just handle it … nothing seems to stress them.

Most of us live somewhere in the middle and our response varies from time to time. So if this is true, it can’t be the external stimulus that does the damage. It must be something in us.

Some physics

I have a PhD in physics, and in physics we define terms very precisely. Stress is a set of forces applied to an object. Those forces cause the object to deform in some way, and that deformation is called strain. Taking these definitions, we can see that, in our lives, stresses are the external forces in your life. Strain is your body’s, your emotional and your behavioural responses to the stress.

Figure 1.2 Stress and strain

It is not the stress that does the damage to you. It is the strain: your response. More particularly, it is the long-term effects of that strain.

Stress can be a good thing

Short-term stress is good – it can rev you up to perform well. So ‘good’ stress includes taking on an exciting challenge, recognising pressure to meet an important deadline, or even sensing that something is wrong and you need to seek out help and support.

Robert had been a stage actor for nearly 20 years when stage fright first struck him. At the time, he was playing the king in Hamlet. He confided in his colleague, Anne, whom he had known since drama school.

‘Whenever I think about going on stage, my palms start to sweat, my heart pounds, I feel a little dizzy and a little sick, and I know I am just terrified about walking on.’

Anne recognised those symptoms; she’d had them for her whole career:

‘Whenever I think about going on stage,’ she said, ‘I feel my heart racing, my mouth dries up and my palms start to sweat, I get that horrid feeling in my tummy, and I know I am pumped up and ready to walk on.’

Your fight-or-flight response simply means you feel threatened. How you interpret that threat – as a real danger, or pressure to perform at your best, is up to you.

A definition of stress

To avoid confusion, in How to Manage Stress, we will refer to the unwanted external pressures in your life as stressors, and your response to those stressors as stress. We will adopt the UK Health and Safety Executive’s definition of stress.

The adverse reaction people have to excessive pressure or other types of demand placed on them.

Health and Safety Executive (www.hse.gov.uk)

So, we feel stress when the pressures on us are too much for our ability to cope with them. Look back at the example of actors Robert and Anne: for Robert, the pressure feels too much for him, whilst, for Anne, it is just the cue she needs to give her best performance.

Long-term strain

When your body is under strain for a long time, and you do not have the opportunity to discharge the stress from time to time, you will be at risk of a wide range of serious medical problems. Chronic back pain can lead to severe damage like a prolapsed or ruptured disc, and elevated heart rate can lead to high blood pressure, cardiovascular disease, strokes and heart attack. Lowered immunity can lead to increased susceptibility to serious infections and has been implicated in increases in the malignancy of certain cancers.

Psychologically, anxiety and withdrawal can trigger underlying mental illnesses, anxiety disorders and social phobias, or depression. The implications of long-term stress on family life can also be severe: conflict, impotence or frigidity, and even breakdowns do occur.

In responding inappropriately to long-term stress, abuse of alcohol, tobacco and controlled drugs are common, as are a range of eating disorders that can lead to obesity, or malnourishment. Violent thoughts can be turned outwards, towards the people around us, or inwards, into self-destructive behaviours, self-harm, and even suicidal thoughts.

Stressors in your life

We all have stressors in our lives. The first steps to brilliant stress management are to recognise them and understand how much stimulation will keep you at optimum levels of arousal and productivity.

Minimum stress

It is a fallacy to believe that too much pressure is the only source of stress. Too little pressure and stimulation can, over a long period, be equally stressful. Figure 1.3 illustrates how there is an optimum level of stimulation that allows each of us to be at our best. That level will be different for you and for me. We are also well able to withstand short periods of over-load and under-load, finding the over-load exciting for a time and the under-load relaxing.

However, if the degree and the duration of over-load or under-load are too great, then each can become a stressor. Once again, your thresholds and mine will be different.

Figure 1.3 The effects of under-load and over-load on your stress levels

What are your stressors?

The three main sources of stress are major changes in our lives, relationships and work. Let’s take a look at some of the typical stressors of each.

Work stressors

Any change in your workplace can be stressful, from a new role to a new boss, to a new location. But there are times when all of these can remain constant, but the pressure to perform well can increase, due to economic circumstances, customer demand, earlier problems, or even in response to a boss who is him- or herself responding to stress they are under. These are further exacerbated if you also have to cope with unreliable equipment, flawed processes, unhelpful colleagues or a frustrating daily commute. If you work unsocial hours or are frequently away from home, then these can add still further to the stress you (and your relationships) are under. Chapter 7 is devoted to managing stress at work.

Change stressors

Clearly, any form of traumatic experience or serious illness or injury is a big stressor, as is the loss of a loved one or the breakdown of an important relationship. Leaving home for the first time, loss of a job, moving home and life transitions like the birth of a child, children leaving home, and retirement are also important stressors. Chapter 8 focuses on managing stress from change.

Relationship stressors

Simply maintaining a relationship is hard work, so when that relationship faces challenges, they will be stressful. Whether at home, at work or in a social setting, conflicts can arise and, if they persist, they will take their toll. Chapter 9 examines managing stress from conflict.

How many stressors do you have?

Work stressors

- Changes

- Pressure to work harder

- Poor resources (equipment, processes, materials)

- Colleagues

- Travel

- Long or antisocial hours

Change stressors

- Injury or illness

- Traumatic experience

- Death or illness of a loved one

- Pregnancy or a new baby

- Job loss or retirement

- Moving home

Relationship stressors

- Divorce, separation or relationship breakdown

- Marriage or moving in with a partner

- Major decisions and disputes

- Sexual problems

- Major holidays and festivals

- Parent–child problems

The secret of managing stress: control

The importance of control

The fact that the symptoms of what we call ‘stress’ arise from your internal response is good news. If it is something inside ourselves, then it is also something that we can control. And if there is one single concept that sums up the source of stress and its solution, it is control. Stress comes from feeling that we do not have control and we solve it by regaining control – control of ourselves, control of our fear, control of our impulses and even control of our environment.

In Figure 1.4, it is the things that concern you, but that you cannot control, which cause you stress. Brilliant stress management is about two things:

- Focusing on the things that you can control, while accepting what you cannot.

- Testing the boundaries to extend your zone of control to its fullest extent.

Figure 1.4 Control in your life

Choice

How you respond to stress is your choice. The one source of all your feelings of being stressed is your mind. The stress does not do the damage – rather, it is the way you respond to it that does the damage, or not.

Think about a dried-up old tree with shallow roots and brittle twigs. If we put that tree under stress, what will happen? In a strong wind, it may blow over … or it may simply snap in two.

Now think of a mighty oak tree, with deep roots and a solid trunk. In the same wind, under the same stress, it just does not move. Its roots go deep into the solid ground and its trunk is strong and confident. Or think of a thin, supple willow. In the greatest of gales it bends and twists, moving this way and that, absorbing the stresses without leaving the place it is rooted to. Each has a different kind of strength – but each is equally strong.

The external stressors in your life are like that gale. How you respond to them is your choice.

Four failures to control

Before we look at taking control, which will fill the rest of this book, let’s start by recognising the ways people find to relinquish control over their lives. Each one is a way to avoid responsibility for our own stress.

Denial

‘There is no problem’, ‘I am in control’, ‘it’s only temporary’. How often have you heard yourself deny what you know deep down: you are in trouble. But don’t be too hard on yourself: denial is the first response we all have to adverse change, so these responses are totally natural. We’ve spent a lot of this chapter referring to your ‘fight-or-flight’ response, but the first reflex we all have when faced with danger is neither fight nor flight: it is fright. Like a hedgehog facing an articulated lorry, we want to curl up into a small ball and hope it goes away.

Splat!

Withdrawal

If you stay in your little ball and hide from the world, then, even if you accept you have a problem with stress, you will get nowhere with controlling it. Locking yourself away may feel like a positive action – stopping others from being hurt by your mood swings, perhaps. At the very best, however, it is a temporary fix, not even the start of a real solution.

Blame

Blame is for God and small children.Louis Dega (played by Dustin Hoffman) in Papillon, screenplay by Dalton Trumbo and Lorenzo Semple Jr, based on the book by Henri Charrière

Another reaction that avoids your taking responsibility is to lay the blame elsewhere: on events, on equipment failures, on other people. If the source of the problem is not your fault, then you can excuse yourself the responsibility for its outcomes. This is a foolish attitude; fault and blame are the wrong concepts. It is important to understand what the stressors are, so you can deal with your response to them, and possibly deal with them directly. But all of the responsibility for yourself lies with you.

It is important to add, though, that this does not mean that you must go it alone. Asking for help is not shirking responsibility: it is finding a way to take it.

Seize control

Brilliant stress management is about how you can take control of your situation and control your stress. The first three steps are:

- Own up to your stress.

- Find someone to talk to.

- Control your behavioural response to stress.

This is the sequence you should follow and is also in order of increasing challenge. When you have made good progress on each of these, you will be able to tackle a range of more powerful approaches, set out in Chapters 2 to 6. Those chapters are not in any order, and offer you choices and options. Some will be right for you, now. Others will serve well at other times or be better suited to different people in other circumstances.

1. Own up to your stress

Before you can do anything about your stress, you must be absolutely honest with yourself:

- How am I feeling?

- Which of my behaviours do I not want?

- What things are causing me stress?

- What is the range of possible consequences?

- How bad is it, on a scale of one to ten?

2. Find someone to talk to

Sharing your problem and asking for help is doing something positive. Turning to a friend, a colleague or a professional for support can help in two ways:

- The emotional support can help you to express how you feel and release some of the emotional pressures you are feeling.

- Another person may be able to help you find – or even offer you – practical solutions to help you regain the control you have lost.

The sooner you can access this help, the better. Ask explicitly for help, telling the other person why it is important to you, and invite them to suggest a time and a place where they will be able to give you the attention you need.

3. Control your behavioural response to stress

On pages 8–10 you learned about Type A behaviour. It may not kill you, but it isn’t doing you any good. The second piece of good news is that you can modify that behaviour. Indeed, this is exactly what Meyer Friedman did, after a heart attack at the age of 55. He saw in himself a strong Type A personality and set out to change it. He died at age 90, in 2001.

Here are six strategies to reduce your Type A behaviour.

Smiling

Look for opportunities to smile – whether it is through looking for the humour in a situation or by deliberately smiling when you want to scowl.

Deliberate slowness

Force yourself to slow down. Choose the slow-moving lane on the motorway, wait patiently to cross the road, offer people a chance to step ahead of you in a queue. Look for opportunities to challenge your ‘rush-rush-hurry-hurry’ instinct.

Associations

The people we associate with have a huge impact on our behaviours, so spend less time with your Type A colleagues and friends and more time with Type Bs.

Planning and time management

Type A behaviour is often reactive and last-minute, so make a point of planning your time and actively managing what responsibilities you take on, and what you reject. There is much more on this in Chapter 4.

Non-competitive activities

Competitive activities can bring out the worst in Type As. So replace some of your competitive activities with other, non-competitive activities.

Reduce hostility

Reducing your levels of hostility towards the people around you will have perhaps the biggest effect on your long-term health. One way to do this is to daily make a mental list of the people you are likely to meet today and, for each one, think of one thing you particularly like, value or respect about them.

- There are a host of emotional, physical and behavioural signs of stress. Stay alert for them and, if in any doubt about their cause, contact your qualified medical practitioner.

- Stress is a natural response to a threat. In nature, our response is designed to subside with time: in our modern lives, it persists because we feel under constant, low-level threat.

- Type A behaviour can lead to stress, and hostility often leads to heart diseases – and others. You can modify these behaviours.

- Work, changes in our lives, and relationships are common stressors.

- The key to dealing with stress is to regain a sense of control in your life.