Today, most leaders want to empower you. They want to give you the authority and responsibility to deliver successful IT projects. They need you to tell them the ground truth. They need you to help them understand the status of your project. They need to know what you need from them as well in order to meet schedule, cost, and quality requirements. They need you to lead your team members—to motivate them to provide IT solutions that meet the users’ requirements.

You need to be ready to perform when they give you the opportunity. The Project Management Institute (PMI®) conducted a Role Delineation Study for the Project Management Professional (PMP®) certification. In this study, they advised project managers to “enhance individual competence by increasing and applying professional knowledge to improve services.” Doing this “requires knowledge of personal strengths and weaknesses, appropriate professional competencies. Requires skills in self-assessment, developmental planning, and obtaining and applying new information and practices” (Project Management Institute, 2000).

In this chapter, I describe how to use self-talk to improve your self-leadership, and I provide you with a process called the Self-Leadership Cycle, which will help you enhance your individual competence as a leader. Through this process, you can learn to take initiative and to exercise a growth mindset. You can become a self-directed leader.

In any circumstance, leaders have to adapt to new situations and changes first, before they can lead their team members. Adapting in this manner requires you to change how you think about leading and working with others.

Let’s take a look at how Tony, a fictional character based on some of my real-life experiences, faces a challenging situation that requires him to adapt his thinking in order to become a project manager.

“Tony, I need to tell you something,” James said. “Not now, man,” Tony replied. “I need to finish this systems architecture document for the server farm. I just got the network load balancing configuration working in the lab and I want to make a final update to the document and send it out for review today.”

“That’s cool—I’ll call you after work,” James replied.

“I am proactive. I keep my commitments and obtain my goals,” Tony thought.

On the drive home, Tony’s phone rang, and James’ picture appeared on the screen. Tony answered in hands-free mode. “James! What’s going on?” he said.

“Hey, I quickly reviewed the architecture doc—man, it looks good. It should get through the review board very quickly,” James said. “Thanks,” replied Tony. “So what did you want to tell me?” “I just got a promotion and I’m going to another program,” said James. “Wow! Congrats!” exclaimed Tony. “What’s the new position?”

“I’m going to be a senior architect on the Dillinger program. You know, the word on the street is that the Baker program that we’re on is going to be cancelled. The great work we’re doing may never go into production, so I decided to apply with Dillinger,” replied James.

“Yes, I heard about that. Smart move on your part. Congrats again, man!” Tony said.

As Tony and James hung up, Tony thought, “Wow, James made the right move. The last time a program was cancelled, the whole team got laid off. I’m a good architect, but I’m no James. I need to figure this out.”

Then Tony said to himself, “I begin with the end in mind. I create success first in my mind and then in my life.”

The next day, Terry, Tony’s boss, asked to see him in Terry’s office. “Uh oh,” Tony thought. Tony sat in a chair across from Terry’s desk. He was wringing his hands, but Terry didn’t notice because he couldn’t see Tony’s hands over the desk.

“You did a great job on the architecture document, Tony,” Terry said. “Thanks,” Tony replied, exhaling. Terry continued, “I’ve noticed that you’re a good architect Tony, but I think you’re a better project manager. I’ve noticed how organized you are, and you’re a good writer. Have you ever thought about becoming an IT project manager?” “I do enjoy project management,” Tony replied, “but I haven’t given it much thought.”

“You should,” said Terry. “I see you with a Six Sigma certification or a PMP®. You should think about that. Once the Baker program ends, there will be new project management opportunities in the company as we stand up the PMO. I recom mend that you prepare yourself.”

“Interesting,” Tony replied. “Thanks for the feedback and the advice. I’ll give this some thought.”

That evening, Tony attended the systems engineering class he was taking for his master’s degree. Aaron, Tony’s professor, made it a habit to mentor the promising students in his classes. Tony admired Aaron because he was smart and successful, and just an overall great person.

Referring to Tony’s self-talk statements during their one-on-one session after class, Aaron said to Tony, “OK, let me hear it.”

“I am proactive. I keep my commitments and obtain my goals,” Tony begins.

“I begin with the end in mind. I create success first in my mind and then in my life.

“I put first things first. I organize and execute around my priorities.

“I seek first to understand and then to be understood. When I listen, I rephrase content and reflect feeling. When I respond, I present my ideas clearly, specifically, visually, and contextually.

“I think win/win. I constantly seek mutually beneficial solutions.

“I seek positive synergy. I utilize conflicting opinions to create third alternative solutions.

“I’m balanced and sharp. I ‘sharpen the saw.’ I constantly learn, do, and commit to activities that promote physical, mental, social/emotional, and spiritual improvement.”

“Great,” Aaron said. “You flowed right through those. Everyone morning and every night, right?”

“That’s right,” Tony replied. “I recorded them on my phone as you suggested. I listened to them every day and every night until I memorized them. Now I recite them at least once a day in the mirror, and throughout the day.”

Aaron had attended a seminar with Lou Tice from The Pacific Institute. He combined Tice’s ideas on self-talk with Stephen Covey’s The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People (Covey, 1989) to create specific affirmations—constructive selftalk—which he used to mentor his students.

“You weren’t yourself tonight in class,” Aaron said. “Something wrong?”

“Things are changing at work,” Tony replied. “The program I’m working on may get cancelled before we’re complete. My boss says I should think about becoming a project manager to prepare for life after this program. I’m trying to visualize myself as an IT project manager.”

“Begin with the end in mind,” Aaron said. “Your boss is right, you know. I have noticed your leadership abilities during class, on group projects. IT projects have a high failure rate, and we need good project managers in the industry. Since you’re thinking so hard about this, it’s obviously something you want to do. Tell you what, why don’t you sign up for the Project Management course next quarter, and then take the PMP® once you finish. You should also use the 10-Page Plan to get through the PMBOK® Guide (Project Management Institute, 2013a) while you’re taking the class. This will help you pass both the PM course and the PMP® exam. The quarter starts next week, so you can begin right away. What do you think?”

“Let me think about it. I’ll email you tomorrow and let you know,” Tony replied.

“Introverts need time to think,” Aaron remembered.

The next day, Tony sent Aaron this message: “I appreciate your advice, as usual. I am ready to make the commitment to become a great IT project manager, and I know with your help, I can achieve this goal.”

Tony followed Aaron’s advice to the letter. Over the next three months, he joined the Project Management Institute (PMI®) and earned an A in his project management course. He followed the 10-Page Plan that Aaron had taught him, studying 10 pages per day, every day, enabling him to read the PMBOK® Guide twice while taking his project management course. This prepared him to pass the PMP® certification exam. Tony then notified the HR department at his employer to add the PMP® certification to his records.

Tony called James at his desk and asked as he picked up, “James, do you have a minute?”

“Absolutely,” James replied. “I heard Baker was cancelled. What’s going on with you?”

“How do you feel about Dillinger?” Tony asked.

James answered, “Great, man, we’re fully funded, and we’re leveraging the work we did on the Baker program.”

“Yes,” Tony said. “Terry told me today that I need to transition my documentation from Baker to you. You’ll be hearing about this from your boss soon. The reason I’m calling is to let you know I got promoted to project manager, and I will be in the new PMO. I’ll be managing projects on Dillinger, among other projects.”

“That’s awesome,” James said. “I’m looking forward to working with you again!!”

Tony sent Aaron another email: “I got the promotion! I’d like to thank you by taking you to dinner—we can celebrate and talk about the next challenge!”

“Outstanding!” Aaron replied. “You’ve embarked on your leadership journey!”

“I am a leader who demonstrates excellent project management skills,” Tony said to himself.

Self-talk is very powerful. What you say to yourself influences who you are in both positive and negative ways. Positive self-talk provides life-giving nutrients to your brain, building neural pathways that enable you to grow and become what you want to become. Negative self-talk is poison. It cripples your mind, debilitates your self-image, and restricts your growth.

We begin our exploration of self-talk with an examination of the self. Then, we will cover inner motivation. Next, you will learn how to rewrite your own code in order to take on the IT geek leadership mindset. Finally, we will talk about improving your self-talk in order to improve your self-leadership.

The self is created in the conscious mind. We mentally integrate our unique collection of perceptions, beliefs, and feelings to form the self. The self consists of three aspects: personality, self-concept, and self-esteem (Kehoe, 2011).

As self-leaders, our challenge is to know ourselves. We are challenged to observe our own personality—our needs, perceptions, and emotional reactions—and the personality we perceive to be required for leaders, and then we make the effort to adapt. We are challenged to observe our own self-concept and then to understand our strengths and weaknesses in how we define ourselves in relation to leadership.

Our self-concept is based on how we see the world, not necessarily how the world is. Our ability to make these changes, considering the complexity of knowing oneself, is quite challenging. Our success rate for adapting to situations that require leadership impacts how we feel about ourselves—our self-esteem.

Our self-concept is in motion, constantly changing through interactions with others. We enhance certain parts of who we are and hide others. We are constantly changing through interactions with others, growing and adapting to meet their needs while they do the same to meet our needs (Kehoe, 2011).

Researchers have found that most people and organizations are able to perform effectively if they strive to understand themselves and each other, then adjust their behavior and change the way they communicate (Institute for Management Excellence, 2003). They have to work to progress toward better teamwork and productivity. But they must first be committed to positive change. Our personality’s enduring characteristics include our needs, perceptions, and emotional reactions. These characteristics influence our reactions to the world across a variety of situations (Kehoe, 2011). Psychologists have found that personality is a consequential system, in which personality characteristics follow as a result or effect of the situations we face. Just as individuals develop Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI) preferences early in life that usually do not change, our personalities exhibit persistent patterns over time that influence our lives (Mayer, 2014).

As we discussed in Chapter 2, the MBTI helps us understand how our conscious minds process information. The tendency of IT professionals to be introverted and to prefer working alone makes effective communications and motivation challenging. This introverted tendency impacts their ability to communicate with their team, peers, and leaders. We also discussed the Big Five Study in Chapter 2, which found that IT professionals scored low on visionary style and may have trouble thinking strategically, which is another core leadership requirement.

While the MBTI preferences may not change, the personality patterns can change as people adapt to their situations, choosing when to use their preferred behavior style and when to use one of their less preferred styles.

IT geeks can learn to adapt to the leadership mindset—to use their less-preferred extraverted preference, to establish and lead others to pursue a clear vision, to value teamwork and collaboration; IT geeks can learn leadership just as a programmer that prefers Visual Basic can learn to code in C#.

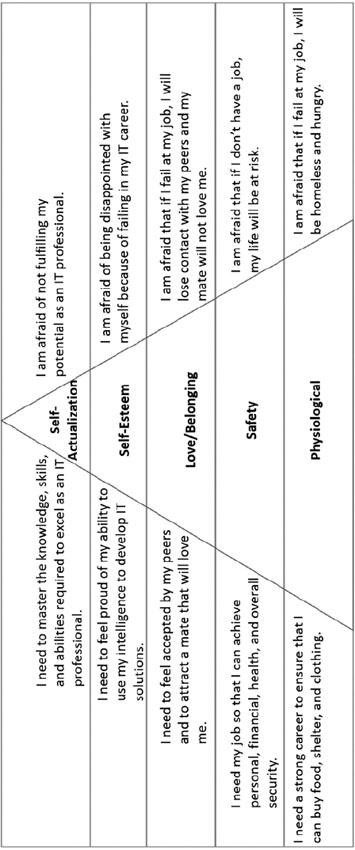

In 1943, Abraham Maslow developed his Hierarchy of Needs Theory to explain human motivation. Figure 4-1 depicts the Hierarchy of Needs. Maslow theorized that we are compelled to respond to five levels of needs: physiological, safety, and social needs (considered lower-order needs); and esteem and self-actualization needs (considered higher-order needs) (Maslow, 2012a).

Figure 4-1 is best read from the bottom up. Maslow’s theory is that people are motivated to satisfy the lower-order needs—to obtain food, water, and shelter; to be safe and secure; and to love and be loved—before satisfying the higher-order needs. Once these lower-order needs have been satisfied, people are then compelled to satisfy their needs for esteem and self-actualization—to be the best they can be and to fulfill their purpose in life (Maslow, 2012b).

Human beings are constantly wanting, working toward the satisfaction of a need. The basic needs are arranged in order of power and influence over the human consciousness. When a need is somewhat satisfied, the next most powerful need emerges and dominates thinking and behavior. Lesser needs may be set aside, forgotten, or denied. Once a person feels the need to self-actualize, he or she may become anxious, on edge, tense, and overall restless (Maslow, 2012b). It is easy to tell when a person feels hungry, unsafe, unloved, or lacking self-esteem, but it is difficult to determine what will satisfy a person’s need to self-actualize.

Self-leadership requires you to find internal motivation to achieve your leadership goals. External motivators, such as paying your mortgage or rent, passing an exam, or completing a project at work, are good positive motivators. But better motivators are those that help you achieve more, that help you to change for the better. Internal motivation does not require an outside stimulus; instead you have a sense of purpose, a determination to change yourself, if necessary, in order to self-actualize, to become all that you can become (Helmstetter, 1982).

Figure 4-1 Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs.

Stephen Covey’s Habit 2, “Begin with the End in Mind,” is based on the principle that all things are created twice, first in the mind, and then, physically, in life (Covey, 1989). No one else knows your needs, goals, and desires like you do, so they cannot—should not—create in their mind what manifests in your life. No one else is responsible for or capable of setting a path for your future.

I have interviewed several people who did not know what they wanted to do. They were working in an area outside of their degree; they had changed jobs several times. They were actually very capable workers, but they didn’t know if they were fulfilled because they did not set out to achieve a particular goal. They struggled to find a position that satisfied their self-esteem needs because they could not visualize or articulate what they were looking for. You don’t have to be that way. You can commit yourself to becoming an IT leader. You can devote yourself to discovering where you are on Maslow’s hierarchy and set out on a journey to self-actualize. Aristotle said, “Knowing yourself is the beginning of all wisdom” (Aristotle, 2012).

An IT geek that has made the commitment to become an IT leader faces such a challenge. You need to find not only external motivation, such as a promotion, but also internal motivation, a sense of purpose that is unique to you, the geek. “Real leaders are guided more by internal than external regulation” (Tice, 2005). Many psychologists believe that you cannot motivate anyone to become something they do not internally agree to become (Helmstetter, 1982). IT geek leaders need to have an emotional connection; a requirement to satisfy a physiological need, a safety need, a self-esteem need, or a need to self-actualize; a need to develop a sense of pride and accomplishment; a belief in themselves; and a fulfillment that comes from living in accordance with their values, beliefs, and expectations.

“You have beliefs and expectations that affect every aspect of your life,” Tice writes, “what kind of person you are morally, socially, spiritually, intellectually. So, in a sense, you don’t have just one self-image, you have thousands. For example, you have a belief about what kind of leader you are, and within that belief, you may have self-images. You may think, ‘I’m a leader on my softball team and as a teacher at my school, but I’m not a leader in my community or church’” (Tice, 2005).

Your belief about your IT geek leadership ability follows the same principle. You may believe you are a leader, that you have a leadership mindset in your family or at school, but not on an IT project.

But you can change this self-image and become an IT geek leader. Taking responsibility for your team means first taking responsibility for your own self-leadership by motivating yourself to adapt, to don the leadership mindset required to succeed in your organization.

As discussed in Chapter 3, a schema is a framework into which we pour our experiences and the emotions associated with those experiences. If we limit ourselves to schemas from days gone by, we cannot grow. We have to live in the present. This is a new day, and we are facing new situations. The fears of the past are not relevant to today’s situation. The constraints that once restricted us do not apply to the challenges we face today.

In Chapter 3, I introduced self-talk as the first element of the Talk Continuum. Self-talk is the voice in our minds that presents our thoughts and feelings in language. What we say to ourselves not only reflects our thoughts and feelings, but also influences our values, assumptions, beliefs, and expectations. What we say to ourselves influences the image we have of ourselves.

Changing your self-talk can change your life. When you begin to picture yourself as a leader, to use your imagination to sense how a leader thinks and feels, your brain builds neural pathways to help you “become” the new picture you create. Whenever you send the same message, or have the same thought, or have the same experience, your brain sends nutrition and energy along that neural pathway, and that pathway gets stronger (Helmstetter, 2013). Weight lifters develop a workout routine that builds muscles through repetition, and the body sends nutrients to those muscles so that they grow stronger and larger. The brain works in a similar fashion. In the brain, the action that builds new neural pathways is not weight lifting, but self-talk.

In 1998, I attended a seminar entitled “Investment in Excellence,” presented by Louis Tice of the Pacific Institute. Lou, who died in 2012, was an outstanding motivational speaker who taught us techniques for visualization, constructive self-talk, setting and achieving goals, and building teams. Lou taught us to create positive, specific affirmations that we were to review every day, morning and night. In 1998, my goal was to earn a Microsoft Certified Systems Engineer (MCSE) certification to complement my MBA and my undergraduate degree in computer science. I wanted to be equally as good with technology as with management. Lou’s techniques helped me accomplish this goal and many, many more. His techniques are recorded in his book, Smart Talk for Achieving Your Potential (Tice, 2005). I am using his techniques right now to imprint into my mind the goal for improving my speaking and writing abilities.

Your self-talk strongly influences your internal motivation. Olympic athletes use it to motivate themselves to perform at a world-class level. Scores of sports teams use it to increase the performance of their players (Helmstetter, 1982). Incidentally, Lou Tice honed his techniques while working as a football coach (Tice, 2005).

The brain builds neural pathways for both positive and negative self-talk. The environment you live and work in, your values, assumptions, beliefs, and expectations—everything you experience—impacts your self-talk (Helmstetter, 2013). You can decide if the neural pathways you create are poisonous weeds or nutritious vegetation. You can directly use self-talk to become what you want to become, including an IT geek leader.

Self-talk can help those who avoid leadership to learn to value good leadership. It can change your assumptions about yourself from “I can never lead” to “I am improving my leadership abilities every day.” Self-talk can change your belief about your work style, drowning out the voice that says, “I’d rather work alone,” with a louder voice that says, “I work very effectively in teams.” It can change what you expect for yourself, transforming “I just do what I’m told” to “I establish and lead others to pursue a realistic vision.”

4.2.4 Improving Your Self-Talk

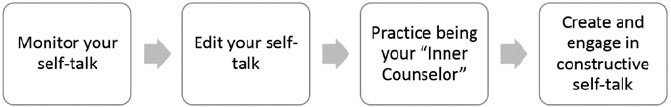

You can take proactive steps to improve your self-talk. Figure 4-2 provides a high-level process for improving your self-talk.

Monitor Your Self-Talk

Monitoring your self-talk requires you to be mindful. You have to “think about what you are thinking about,” as if you are a third person listening to the chatter going on inside your head. Accomplishing this step makes you self-aware.

Table 4-1 explains how to monitor your self-talk.

Edit Your Self-Talk

When you listen to your self-talk, you identify the negative thoughts about yourself that are detrimental to improving your leadership abilities. No one controls your thoughts but you, so you siphon out the poison, replacing the negative with positive.

Your new self-talk, replacing negative thoughts with positive thoughts, may not sound like you at first. However, repeating the processes provides your brain with new instructions, and your brain will do what you repeatedly tell it to do (Helmstetter, 2013). If you change the way you think, you will change the way you act. If you learn to think like a leader, you will become a leader.

Figure 4-2 Self-talk improvement process.

Table 4-1 Monitor Your Self-Talk

Step | Instructions | Self-Talk |

Monitor your self-talk | • Listen to everything you say or think. • Pay attention to the poisonous things you say about yourself that could work against you. | Listen for thoughts such as: • “I don’t know what to say to senior leaders.” • “No one listens to me.” • “The customer makes me nervous.” • “I will never understand the big picture.” • “I never do well working with teams.” • “I am not cut out for leadership.” |

Data derived from Helmstetter, S. (2013). The Power of Neuroplasticity, p. 161.

Table 4-2 provides instructions for editing your self-talk.

Table 4-2 Practice Your “Inner Counselor”

Step | Instructions | Self-Talk |

Edit your self-talk | • When you anticipate that you will say something negative to yourself, something that should not be imprinted into your mind, stop. • Instead of saying the negative phrase, replace it. Think your best and not your worst. Rewrite and reframe. • Choose a positive thought to record in your brain. | Sample self-talk changes: • “No one listens to me” becomes “Everyone respects my point of view.” • “I can’t talk to my senior leaders” becomes “Senior leaders value my input.” • “I’m not comfortable delivering bad news” becomes “Leadership needs to hear the truth and they trust me to deliver it.” • “I don’t understand the customer” becomes “I’m the bridge between the customer and my technical team.” |

Data derived from Helmstetter, S. (2013). The Power of Neuroplasticity, p. 162.

Editing alone will not remove all of your negative programming, but it keeps you from getting more of the same.

Practice Being Your “Inner Counselor”

During this step, you take on the role of what you imagine to be your more enlightened self. You create an image of yourself that is your coach or mentor. This “Inner Counselor” provides you with inspiration and guidance for improving your leadership abilities.

Table 4-3 explains the role of the “Inner Counselor.”

Of course, your “Inner Counselor” is no substitute for an actual counselor, but it supplements your experience with your coach, mentor, or professional counselor.

Table 4-3 The Role of the “Inner Counselor”

Step | Instructions | Self-Talk |

Practice being your “Inner Counselor.” | • Image your “Inner Counselor” to be a more enlightened form of yourself. • Give this image of yourself the authority to work with you to help you reduce fear and to identify and correct false notions. • Your “Inner Counselor” uses cognitive, inner dialogue to inject reality into your self-talk so that you focus on the current situation and not the irrelevant past where the negative thoughts originated. • Meet with your “Inner Counselor” daily in order to break old, negative habits and replace them with new, positive habits. • Speak to yourself in the second person, using “you” instead of “I.” | Here is an example of an “Inner Counselor”: “Alright, Tony. I know you’re nervous about presenting the project schedule to the CIO. You need to calm down and relax. You and the team worked really hard to develop the schedule. You have already socialized it with the CIO’s office—they know about the delays the vendor caused and your contingency plan. Your nervousness stems from that time five years ago when your presentation didn’t go so well. You have learned much since then, and those people aren’t even here—but you are! And you have had many successes since then! You’ve rehearsed and you know this project cold! You can do this!” |

Data derived from Helmstetter, S. (2013). The Power of Neuroplasticity, p. 164.

Create and Engage in Constructive Self-Talk

Your creative subconscious mind enforces your behavior. It maintains your present version of reality, causing you to act like who you believe you are. When you wake up in the morning, you don’t have to rediscover who you are. Your creative subconscious maintains this image and thereby allows you to maintain your sanity. It provides consistency for who you are (Tice, 2005).

Your creative subconscious always maintains your presently dominant self. This is the self that you present to the world, the self that everyone reacts to. Maintaining your idea of reality is more important than anything else—any ambition, drive, or goal that you set. Constructive self-talk, tempered by your inner counselor, tells your brain what reality is, changing the way you think and therefore changing the way you act (Tice, 2005). Table 4-4 provides instructions for creating and engaging in constructive self-talk.

Table 4-4 Create and Engage in Constructive Self-Talk

Step | Instructions | Self-Talk |

Create and engage in constructive self-talk | • Create your self-talk in the present tense—“I am …” “It is …”. • Create specific self-talk. Include the details, and don’t be vague. • Avoid self-talk that produces unwanted side effects—pushing yourself too hard can cause stress and illness. • Keep your self-talk simple and easy to use. • Create self-talk that is practical and achievable. Plant your self-talk on solid ground, not on miracles. • Create self-talk that stretches you and demands the best of you. | Examples: • Present tense: “I really am a very special person.” • Specific: “I accept responsibility for leading the Dillinger Software Development Team.” • Avoid danger: “I will work 16 hours a day until I complete this project.” • Simple: “I never worry.” • Practical/achievable: “I read leadership books every day and I practice what I learn.” • Stretch goals: “I can clearly see myself successfully leading a team of 20 software engineers and developers, delivering a critical project on time and within budget.” |

Data derived from Helmstetter, S. (2013). The Power of Neuroplasticity. Gulf Breeze, FL: Park Avenue Press; and Tice, L. (2005). Smart Talk for Achieving Your Potential: 5 Steps to Get You from Here to There. [Kindle Version].

My inspiration for the self-talk example provided above in the section Practice Being Your “Inner Counselor” came from a couple of my emotional experiences. I was a shift lead in an operations center as a 20-something US Air Force Airman. While I was in charge, a special operations event occurred that we had to respond to. I can’t go into details concerning the event, but I can say that I was responsible for making sure the team followed procedures correctly and then reporting the results of our scientific analysis to higher headquarters. I remember how embarrassed I was because my voice was trembling and my hands were shaking. This was long before the Lou Tice seminar. I plowed through it, and we were successful, but I did not get any style points. I knew the bits and bytes cold, but I was not prepared to interact with senior leadership.

“If you want to be a leader, but believe yourself a follower, you will automatically act like you believe yourself to be when a crisis occurs,” writes Lou Tice in Smart Talk to Change Your Life. “If you feel out of place, tension constricts your vocal chords so your voice changes. That’s why, when someone gets up in front of a group of people and says in a squeaky, timid voice, ‘I’m looking forward to this,’ you sense they are lying” (Tice, 2005).

As that young shift lead, I hoped that we would not experience an event while I was in charge. I was certainly not looking forward to leading. My self-image was that of a programmer, as a technologist, as an IT geek. I was in a leadership position, but I did not have a leadership mindset.

I was working among the technical elite of Air Force enlisted personnel. We all needed high test scores to get accepted into our career field. I desperately wanted, needed, to be as good they were, to be as confident and accomplished as they were. However, during this operations event, I fell short of the mark, and I knew I had a lot of work to do.

Not long after this event, I took a speech class while in college. Then I earned an undergraduate degree, and after that, the Air Force sent me to leadership school with over 100 of my peers. Unlike a few others, I decided to apply myself at school because I needed to embrace what was taught in order to achieve my goals. At leadership school, I won the Communicator’s Award as well as the Leadership Award, presented to the sole honor graduate. Next, I attended Officer Training School and Computer Officer Training School, where I was an honor graduate. Both of those schools required me to participate in communications training, both speaking and writing. Prior to departing from the Air Force, I attended the Lou Tice seminar, and I earned an MBA, which also provided extensive communications training.

After becoming a civilian IT project manager, I needed to make a presentation to the CIO of a large organization concerning the results of our analysis of a global workstation modernization requirement. I developed the presentation with the team, and I knew the material cold. But I did not rehearse, as I was taught to do for critical presentations. I thought I could “wing it.” Although I was prepared, and although I had given many successful presentations up to that point, I was still haunted by my experience as a young shift lead, stumbling through leading our response to an operational event. I stumbled through the presentation—again, no style points.

When it comes to presentations, this geek is “hit and miss.” The more I prepare the better I am. I joined Toastmasters so that I could constantly hone my presentation skills and so that I would have a fresh library—schemas—of recent successful presentations that I can now draw from for confidence. I am nervous almost every time, and Toastmasters allows me to practice handling that nervousness, channeling my nervous energy to a successful presentation. The more opportunities I get to practice overcoming nervousness, the better the outcome.

I have presided over hundreds of meetings for the dozens of projects and programs I have led. I have presented at seminars at churches and colleges in my area. I have received many compliments for my presentations at award ceremonies and the like. Why? Because now I am mindful and self-aware. I have worked hard to edit out previous failures and poisonous self-talk. I know what I need in order to be successful in this area, what I need to do and how I need to think. I have learned to rewrite my code. Since Lou Tice, and since my poor performance in front of the CIO, my daily self-talk has included, “I am an excellent public speaker and I am very comfortable in this role.” Repeating this specific affirmation to myself before I speak, whether at Toastmasters or in a professional setting, gives me confidence, reminds me of my public speaking successes, and calms me down.

Now that you understand the power of self-talk, let’s examine how self-talk can be combined with what I call the Self-Leadership Cycle to create and strengthen your IT geek leadership mindset.

William Deming is known for the Plan-Do-Check-Act (PDCA) Cycle, a four-step model for carrying out change (isixsigma, n.d). Author Stephen Covey concludes the chapter “Habit 7: Sharpen the Saw,” in The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People, with a description of an upward spiral, in which we learn, commit, and do activities that take us to increasingly higher levels of effectiveness in life (Covey, 1989). These two models inspired what I call the Self-Leadership Cycle, as depicted in Figure 4-3.

Let’s take a closer look at the Self-Leadership Cycle in relation to improving IT geek leadership.

Figure 4-3 The Self-Leadership Cycle.

Have you ever made a vow to a country, an organization, or a person? When US military members make a vow to defend their country, they raise their right hands and say, “I solemnly swear to defend the Constitution of the United States against all enemies, foreign and domestic, so help me God.” School children in the United States are taught to put their hands over our hearts and “Pledge allegiance to the flag of the United States of America.” We make enduring commitments to our country and to our loved ones, but how about to ourselves? In the Commit phase, we make the same magnitude of commitment to ourselves to become IT leaders.

As an IT geek seeking to become a leader, your commitment begins with a choice. Commitment requires you to be mindful, “to pay attention to how you are paying attention” to the tasks and make the effort necessary to reach your goal of becoming an IT geek leader. You need to be mindfully aware of where you are and where you want to go as well as committed to changing your mental state so that you will first think like, then feel like, and finally behave like an IT leader.

The mindset you have as a team member is not the mindset required for leadership. You have to practice thinking like a leader. When I was a young Air Force Staff Sergeant, I dreamed of becoming a commissioned officer. I started to observe the officers around me, to listen to what they said and to watch how they behaved in order to understand how they thought. I would emulate how they approached situations, and then I would try to take the same approach to address challenges as I imagined an officer would. From my perspective, if I started with the academics first, understood the best practices and understood what schools were teaching about the subject matter related to the issue I was facing, and then applied those academics to the situation I faced, my approach would be as sound as the approaches of the officers around me. I thought about this goal every day and worked hard to adapt my mindset. Eventually, I got the opportunity to apply for Officer Training School, and I believe this thought process emulation exercise helped me successfully transition into the commissioned officer role.

There is power in the choices we make. Repeating the same choices again and again builds neural pathways in our brains that reinforce those choices. Positive choices build positive habits (Helmstetter, 2013). Choices concerning whether we will make the effort to be good communicators, to interact and collaborate with other team members, to develop and maintain relationships with our leaders and customers, to have an open mind and make the effort to use dialogue to understand the customer’s requirements, to choose to pursue world-class solutions even when we don’t agree with the requirements, to choose to courageously report bad news early and often—all of these choices determine how well we lead. As a self-leader, you need to understand where you are in these areas and make the commitment to form the positive habits to improve yourself in these areas. No one can make this commitment for you; only you can mindfully make this choice concerning your own thoughts, feelings, and behavior.

To transform yourself into an IT geek leader, choose to make the commitment to change your mindset. Learn to use self-talk to imprint this goal and build leadership habits, to create neural pathways for leadership that are stronger than the neural pathways for your current behavior.

When we make a commitment, we proactively take on responsibility for our own personal development. We take responsibility for developing a leadership mindset, for editing out what author Stephen Covey calls reactive language and replacing it with proactive language. According to Covey, reactive language absolves you from responsibility (Covey, 1989). As leaders, our team members, our peers, and our senior leaders depend on us to take proactive actions. This begins with proactive self-talk, editing out reactive language and replacing it with proactive, committed self-talk (see Table 4-5).

Covey said that there are two ways to put ourselves in control of our lives immediately. We can make a promise and keep it, or we can set a goal and work to achieve it (Covey, 1989). Both of these actions require commitment and build our credibility as a leader. As we make and keep even small commitments, according to Covey, we establish inner integrity that gives us the awareness of self-control. We gain power—courage and strength to accept responsibility for our lives. We set an example for our subordinates to follow and our peers to emulate.

Table 4-5 Reactive and Proactive Self-Talk

Replace Reactive Self-Talk | With Proactive Self-Talk |

“I can’t please this customer.” | “I listen in order to understand the issues and take action to improve processes.” |

“He makes me so upset.” | “I am in control of my feelings.” |

“They don’t want to hear what is really happening.” | “I choose to communicate the ground truth effectively.” |

People in organizations are capable of change and growth. They can work toward progress, toward better teamwork and productivity. But they must first be committed to positive change.

IT geeks are a smart bunch. According to the US Census Bureau, in June of 2013, 68% of IT professionals in the US hold a bachelor’s degree or higher, and an additional 24% had some college or an associate’s degree (Department of Professional Employees, 2014). Many others have earned IT certifications and do not have any college.

We need our best and brightest IT professionals to lead IT projects, and many who have undergraduate and graduate degrees are doing just that all over the world. However, the Computer Science Curricula 2013, which is the curriculum guideline for undergraduate degree programs in computer science and information technology, does not include leadership in the body of knowledge (ACM/IEEE, 2013). The curriculum does, however, promote the principle for continuous learning, expounding, “Curricula must prepare students for lifelong learning and must include professional practice (e.g., communication skills, teamwork, and ethics) as components of the undergraduate experience.”

To become an IT geek leader, you need to make a commitment to lifelong learning about leadership. During my leadership journey, I found that many IT professionals that I worked with avoided tasks that required them to write and to speak, and that they missed out on opportunities to present information to customers and to leadership. Because my peers avoided these job requirements, I knew that if I embraced speaking and writing, while remaining adept in technology, I’d have job security. Like a fireman that runs toward a fire instead of away from it, I made a conscious and continuous effort to overcome the fears that kept others in the shadows and on the sidelines.

You have the same choice. Your brain is a chemical organ that uses chemicals to develop neural pathways for your thoughts. Choosing to be mindful adds strength to those pathways, forming habits for activities that lead toward attainment of goals. Research has shown that concentrating for 10 to 15 seconds or more on a thought upgrades that thought from short-term memory storage to longer-term memory storage. You are in charge, not your brain, so you can mindfully instruct your brain that you are not just an IT geek, but an IT leader. And you can do this in a way that you enjoy; you are free to make yourself not only an IT geek leader, but an IT geek leader who enjoys his or her work (Helmstetter, 2013).

After you have made the commitment to change your thought processes about leadership, learn everything you can about how to be a strong leader. Take classes, buy books, go to the library, subscribe to periodicals, and read Internet sites. Create a “Smart-book”—a three-ring binder with articles, clippings, copies from library books, and the like that you can use as references.

I love how small, incremental steps can add up to something very substantial. Did you know that if you read 10 pages a day, a task that probably takes about 15 to 20 minutes, 10 pages a day every day for a year, you would read 3,650 pages in a year? Assuming the average book has less than 300 pages, you would read at least 12 books in a year. If you read 12 books about leadership in a year and apply what you learn, you will be a far better leader than your peers (and maybe even your bosses). In the Learn phase, you commit yourself to finding out whatever you need to know to become a great leader. Knowledge is power—commit yourself to becoming powerful!

This type of dedication to learning requires a growth mindset instead of a fixed mindset. Dr. Carol Dweck, a psychologist at Stanford University, defines a learner with a fixed mindset as someone who believes that intelligence is a fixed trait. People with fixed mindsets believe a person is either smart in a given area or not. People with a fixed mindset usually exert much less effort to learn material they believe is too difficult to grasp (Doyle and Zakrajsek, 2013).

In contrast, people with growth mindsets toward learning believe that intelligence grows as one obtains new knowledge and skills. Failure to them is a trigger that they need to work harder to overcome the challenges they face in order to succeed (Doyle and Zakrajsek, 2013).

A person can have a fixed mindset in one area and a growth mindset in another. For example, an IT professional can have a growth mindset toward software development and a fixed mindset toward leadership.

As discussed earlier, your brain is capable of developing new neural pathways based on your experiences. According to Jesper Mogensen, a psychologist at the University of Copenhagen, neurons in the brain grow new connections, build new neural pathways, when we learn. Our intelligence is not fixed (Doyle and Zakrajsek, 2013).

To become an IT geek leader, you have to overcome the fixed mindset toward learning to be a leader. You need a growth mindset; you need to believe that if you can learn the complexities of IT, you can learn anything, including leadership. A leadership mindset is a growth mindset focused on leadership.

Here are some daily self-talk suggestions that can help you overcome a fixed mindset about leadership and develop a growth mindset:

• “I am smart and creative. I continually increase my leadership knowledge.”

• “I am a lifelong learner. I can learn anything I want to learn.”

• “I accept the responsibility to learn to be a great leader.”

Proverbs 12:1 says, “If you love learning, you love the discipline that goes with it—how shortsighted to refuse correction!” While you are learning what you need to know to succeed, you are going to need guidance from someone who can keep you on track and help you make decisions.

No one knows everything. It’s important to get guidance from someone you respect who has performed similar tasks or who has been on similar projects. Seeking mentorship allows you to create a dialogue with someone and get direction on where to find the information you need. A mentor can tell you what works and what doesn’t, and what to look out for. A mentor can direct you to other people who can help you.

We see the world the way we are, not the way that the world is (Kehoe, 2011). Scotomas, blind spots, cause us to see what we expect to see, hear what we expect to hear, think what we expect to think (Tice, 2005). “I don’t communicate well—I get too nervous.” “I am not good with people; I have never been a people-person. I’d rather deal with computers.” “I’m not the leadership type.” Locking in such beliefs shackles you, prevents you from being anything other than what you tell yourself you are.

Your mentor can help you see yourself and what you are capable of from a different perspective. He or she can help you see the blind spots and unlock the shackles that prevent you from meeting your full potential.

You need a mentor who can show you the way. But don’t wait for your mentor to find you—take the initiative to find a mentor. You can join organizations and clubs in your area of interest, such as the Project Management Institute and Toastmasters International. Seek mentorship, and you will find the direction and encouragement you need to become a strong leader.

Management and psychology students generally learn about Abraham Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs Theory, discussed earlier. During the experiment phase, the goal is to mindfully pursue what Maslow defined as a peak experience. This is a profound moment of love, happiness, understanding, or rapture; an experience in which a person feels in harmony and balance with the world around him or her. A person who self-actualizes, who meets his or her full potential, has many peak experiences (Maslow, 2012a).

Now it’s time to turn your commitment, your learning, and your mentorship into a planned peak experience. For example, the PMI® provides volunteer opportunities that will help you develop your leadership skills. The members of your local PMI® chapter can help you face and conquer your leadership challenges.

Because IT geeks are generally challenged when it comes to communications, I highly recommend Toastmasters International. Toastmasters provides opportunities for leadership as an officer in the Toastmasters club and during club meetings. Toastmasters will provide you with opportunities to develop and present speeches. Your fellow Toastmasters will gently evaluate your presentations. All of this mentorship occurs in a non-threatening environment that will help you grow as a communicator and a leader.

Experimenting with leadership in this way gives you the opportunity to visualize yourself committing, learning, being mentored, then planning and implementing a project. When you are successful, your self-esteem and belief in yourself as a leader will increase, and for a moment, you will self-actualize. It will be an experience you will not forget because you will develop a schema, as discussed in Chapter 3—a new neural pathway that you will draw on the next time you face a leadership challenge.

If you are taking on a leadership role for the first time, you may be nervous. You may fear failure. But if you have prepared yourself by studying and if you have a mentor to lean on for advice, you have the resources you need to be confident with your commitment. You have made a commitment to yourself to perform because you know you will be one step closer to becoming an IT geek leader. Experimenting allows you to make excellent contacts and to build a reputation for yourself as someone with outstanding character and determination.

I highly recommend keeping a Leadership Journal. This is just a notebook that you keep with you to write down and review your thoughts, feelings, plans, goals, and self-talk. It can help you stay focused and on track during your self-leadership journey.

Here are a few steps that can help you with your experiment:

Experimentation Exercises

1. Visualize yourself performing in a leadership role. Imagine what you will see, hear, and feel as you do lead. Think about situations you might encounter and how you will react. Rehearse presentations until you have them down cold.

2. Develop an action plan for the leadership tasks that you plan to perform. Ask your mentor and someone else on the project to review the plan and provide feedback.

3. Meet with all of the people involved in the project and communicate the plan. Get their feedback and address their issues.

4. Lead, communicate, correct, and encourage.

5. Follow up with your team members, your leadership, and your mentor. Keep everyone informed and keep the communications process flowing.

6. Thank everyone involved in the process. Consider showing your appreciation to those who helped you through this process with special gifts and recognition.

7. Write in your Leadership Journal any notes or observations you make along the way.

The last phase is Review and Analyze. Now it’s time to take a step back and think about what you have learned.

As you consider your leadership experience, understand that you don’t have to be perfect. Perfection is neither attainable nor required. No one is perfect, and no one expects you to be. Everyone has challenges, setbacks, and shortfalls.

Researchers have found that 77% of our mental programs are false, counter-productive, harmful, or work against us (Helmstetter, 2013). This means over three-fourths of our thoughts distract us from reaching our goals. You may have thoughts such as, “I am afraid of being in charge. What if I mess up? I will lose my job and get evicted. No one likes me and they are not going to follow me. No one listens to me. I am too nervous to lead my team. We failed when I was in charge of field day in high school, and if I am in charge, we will fail now. I am not a born leader like Tony is. I will never be as good as he is.”

As much as we try to remain positive and focus on transforming our minds, we are distracted and interrupted by trips down mental pathways that lead in a different direction than the one we intended to follow.

In the Bible, the Apostle Paul finds himself in such a situation while trying to lead a righteous life. Romans 7:17–23 (The Message Translation) says, “But I need something more! For if I know the law but still can’t keep it, and if the power of sin within me keeps sabotaging my best intentions, I obviously need help! I realize that I don’t have what it takes. I can will it, but I can’t do it. I decide to do good, but I don’t really do it; I decide not to do bad, but then I do it anyway. My decisions, such as they are, don’t result in actions. Something has gone wrong deep within me and gets the better of me every time. It happens so regularly that it’s predictable. The moment I decide to do good, sin is there to trip me up. I truly delight in God’s commands, but it’s pretty obvious that not all of me joins in that delight. Parts of me covertly rebel, and just when I least expect it, they take charge.”

Paul struggled, as every leader does, but he never gave up. He became a great leader. He went on to establish several churches and to write thirteen letters that are included in the Bible. He was just a human being like you and me. He persevered and accomplished great things despite feeling he “did not have what it takes.”

As a leader, when you make a mistake, commit yourself to recovering quickly. Your followers and the leaders in your organization will be watching you and paying attention to how you handle adversity. Tell yourself, “Next time, I will …” and proceed with instructions to yourself on how you will avoid making the same mistake in the future. In your plans, include time to recover and learn from your mistakes. The better you are at recovering, the more effective and respected a leader you will be.

After you have completed a leadership experiment, take some time to reflect on what you have learned. Are you taking your commitment seriously? Are you closer to reaching your goal of becoming a strong leader? What went well? What did not go so well and where do you need to improve? What additional help do you need? What is the next step? How have you grown? Are you closer to reaching your leadership goal? Do you need to modify your goal—perhaps make it more realistic, or perhaps speed up the deadline? Are you happy with your results, or disappointed, and why? Was your mentor helpful? Would you seek advice from him or her again? In your Leadership Journal, write down the following:

Leadership Journal Exercise

1. What went well in your experiment?

2. What did not go well or had unintended consequences?

3. If you had to complete the experiment again, what would you do differently?

4. What would you recommend, as a mentor, to others doing similar projects?

Now consider what you learned about yourself. Perform the following free-writing exercise:

1. On a clean page in your Leadership Journal, write the phase “If I could change one thing about myself …”

2. Complete the phrase and write non-stop for five minutes.

3. After five minutes, take a 10-minute walk.

4. Come back and read what you wrote. How do you feel about what you wrote?

Think about these things and consult with your mentor. Put a plan together and repeat the Self-Leadership Cycle. Over time, and with effort, you will become comfortable with leadership. You will build neural pathways that you can traverse during your next leadership challenge.

Like Tony in the “Things are Changing” use case, you can use self-talk to change your mindset, to don a leadership mindset, and to take on a leadership role with confidence. You can make a commitment to becoming a leader, to learning the discipline of leadership, to finding and trusting a mentor to guide you along the way, to engaging in leadership experiments, and to reviewing and analyzing your progress toward reaching your IT geek leadership goals. I’m a geek who overcame my communications weakness and embarked on a leadership journey. I’ve stumbled, but I’ve also found success. If I can find a leadership mindset that fits me, I’m sure you can find one that fits you.

Now that you understand more about self-leadership, let’s move on to Chapter 5, where we will discuss what it means to be an effective follower and the relationship between effective leadership and effective followership.

Developing Your Leadership Mindset

The exercise below steps you through the Self-Leadership Cycle presented in this chapter in a manner that can help you develop a leadership mindset.

1. Take the Leadership Questionnaire at the end of Chapter 2.

2. In your Leadership Journal, list the areas in which you rated yourself with a 2 or below.

3. For each item you listed in Step 2:

• Visualize yourself performing the task in a way that you would rate yourself a 3 or 4. Imagine how you would feel if you were to be successful at it.

• Listen for poisonous self-talk concerning these items. What do you need to change in order to improve your self-image for performing this task?

• Write down a constructive self-talk sentence for the item you need to change. Recite your new, positive self-talk every morning and every evening in the mirror. Record it and play it back to yourself each day.

4. Research what you need to learn in order to be successful in any area you listed in Step 2. What books can you read? What projects do you need to research at work? Who do you need to talk to at work who can help you understand the business goals and objectives and how they relate to your project? Create constructive self-talk for the areas in which you are working to improve.

5. Identify someone you trust at school, work, or your PMI® chapter who is successful at the tasks with which you need help. Seek out this person as a mentor. Ask him or her to help you refine your plan to improve in the areas in which you are challenged.

6. Identify opportunities to implement your new knowledge and initiatives on your project.

7. Speak with your mentor about your experience and plan your next iteration.