Community Spirit

Small-Town Identities That Bind

ALTHOUGH THEY LIKE THE SLOW PACE OF LIFE and small scale of their towns, residents most often say the best thing about living in a small town is simply the people. They know one another and regard one another as good neighbors. They appreciate seeing familiar faces and waving to people they know on the street. It is a kind of storybook existence, as people describe it—like a scene from a 1950s’ television program. But folksy depictions wrapped in half-hour segments for family viewing are hardly reality. We need to move the camera in for a closer look.

Myrna Zlotnik lives in a coastal community of six thousand that is seventy-five miles from the nearest city of any size and a seven-hour drive to the closest large city. She and her husband live in a small cabin-size house that is heated by an old-fashioned woodstove. Hauling wood keeps them busy during the long winter months. She savors the smell of the Douglas fir that grow tall along the Pacific coast. When she thinks about the future, she asserts that she would never live anywhere else again. She says she would be dead by now if she had stayed in the city where she grew up. The slow pace here—“no apparent urgency to get from point A to point B”—keeps the stress level low. If a town gets too large, she explains, people become pushy and, well, you just “start bumping into stuff.” She especially values the friendly atmosphere of the community.

There is some truth to the view that small towns are friendly places in which people know their neighbors and generally get along with one another. In a national survey, for example, 44 percent of respondents living in small nonmetropolitan communities said they knew almost all their neighbors, whereas that was true of only 14 percent in larger metropolitan areas.1 But community spirit involves more than simply knowing one’s neighbors—especially when one’s neighbors, even in the smallest communities, constitute only a fraction of the town.

Mrs. Zlotnik believes that the clichéd saying about everyone knowing everybody else is a true description of her community. She is a gregarious person who relates easily to friends and neighbors. But when pressed, she says she probably knows only about 10 percent of the town’s six thousand residents by name. She has about thirty close friends who share similar enough interests that they get together for dinner parties once in a while or just socialize at the café, telling stories over plates of pasta and keeping the conversation light.

In this respect, her social circle is an affinity group, just as it probably would be if she lived in a city. Two important aspects of small-town life make her social relationships different, however. One is that everybody—rich, poor (like herself), or in between—eats at the same café and buys gas at the same filling station. The faces she sees at the café and gas station are familiar enough that she regards these people as neighbors, even though she may not know them by name. She also feels that living in the same place and seeing one another this frequently is a leveling experience. She thinks of her neighbors as her equals. They also talk about watching out for their neighbors’ children, keeping their eye out for one another, and participating in community projects.

This example illustrates that community is a concept that people construct and maintain through the ways they talk about it. Its existence depends only in part on the fact that people actually get together at dinner parties. It does not require that everyone literally knows everyone else. Community is reinforced by the place that throws people together and the discussions that occur in these places. No individual person knows everyone, but it may seem as if they do because they talk about the ones they know, and emphasize the commonalities and norms of neighborliness that they consider important.2

Community spirit resides in activities and organizations along with the resulting perceptions and narratives that arise. Making and sustaining these activities and organizations takes effort. Community spirit depends not only on the fact that people live in small out-of-the-way places with tight networks and scant populations. It also relies on residents working together, sharing common interests, and celebrating their shared ideals. As one community-minded resident puts it, “It is an action and a feeling. I feel it when I’m doing something for the town.” Community spirit also inheres in unspoken codes of behavior that govern social relationships. This is why newcomers often find it awkward adjusting to small-town life, but also why newcomers are an important source of insights about the nature of camaraderie in these places.

Residents of small towns talk passionately about the social ties that forge solidarity in their communities. Many say they have stayed in small communities or moved to one because they were looking for close neighborly social relations—and are pleased to have found them. They worry about the potential loss of community as times change and they resent decisions that seem to undermine the most basic sources of community spirit. At the same time, there are surprises. For many residents, it is not the camaraderie that instills loyalty to their community as much as it is their attachment to the place, their love of the familiar ambience (however modest it may be), and the feeling they have of being close to the natural environment. For some, small towns are appealingly devoid of social constraints, offering freedom, individuality, and even anonymity.

It is no accident that the word spirit is so often appended to references about community. Spirit implies culture—an emotional attachment expressed in and reinforced by a repertoire of symbols. The town’s name and location, its school, the school’s mascot, the community’s history and its commemorative festivals, the unwritten norms that govern routine sidewalk encounters, and the symbolic boundaries that differentiate newcomers from old-timers and townspeople from urban residents all contribute to the spirit of community. With slight modification, what anthropologist Benedict Anderson famously observed of nations pertains equally to towns. Community is imagined “because the members of even the smallest [ones] will never know [all] of their fellow-members, meet them, or even hear of them, yet in the minds of each lives the image of their communion.”3

To say that community is imagined is not to say that it is only a mental fabrication. The fact that a small town occupies a particular place on the map, has a name and a history, and is defined geographically well enough to be easily recognized is important. When respondents in a national survey were asked what came to mind when they heard the word community, the top choice among suburban and city residents was their “neighborhood,” but among residents of small towns, it was their “town.”4 That is crucial because conceptualizing social categories does not come naturally. In an interesting study of community service organizations, sociologist Paul Lichterman found that even the most dedicated volunteers usually thought of their recipients as individuals, whereas only with effort did they conceptualize themselves and their recipients as representatives of larger social categories.5 For townspeople, “town” is a social category that comes easily to mind but is also reinforced through events and public discourse.

Much of the social science literature in recent years has highlighted social capital. Social capital consists of network ties with specific individuals, either with ones who are similar to oneself and thus constitute relationships of bonding, or with different others with whom bridging occurs. This view lends itself to enumeration. If people visit frequently with their neighbors over dinner, and if they see one another at club meetings and bowling alleys, community is said to be strong. If those social ties weaken, community is considered to be weakening. Those kinds of participation are significant in small towns, as I have suggested. But they are by no means all that make a small town a community. It is important that residents are able to conceptualize their town as a community, and not simply to visit or email their closest friends. The town as a social identity is preserved and made real through symbols that represent it, and through the narratives that blossom around these symbols.6

SCHOOLS AS SOURCES OF COMMUNITY SPIRIT

In all but the smallest towns, nothing serves so effectively to instill community pride as the local school. “Our school is central to everything,” a resident of a town with only a thousand people and hardly any stores left on Main Street asserts. “We have one school K through 12. Old-fashioned school. Wonderful, wonderful school. It makes us proud.” This is a man who has no immediate connection with the school. His children are grown, and he is retired, but like many residents of small towns, he regards the school as the focal point of the community. People gather at the school for games and plays, town meetings and holiday events. “It isn’t perfect,” he acknowledges, “but it is a very good school, and our whole community revolves around it. Nobody plans anything in this community without checking the school program. Everyone gets the school calendar, and that is the social calendar for the community. Everything revolves around it.”7

If a school closes because of declining population or consolidation, the blow to the community is more than simply having to see the remaining children bused to another town. It strips the town of a critical piece of its identity. “You jerk the school out of there,” Mr. Steuben says, “and you just cut the town’s throat.” He remembers the little towns in Montana, Oklahoma, Texas, and Wyoming that he traveled through as a custom cutter. They had a couple of grocery stores, a hardware store, a telephone office, and a school. But then, he figures, two-thirds of them lost their schools. He is all for good education and is glad to live in a larger town with strong schools. But for the small towns, he thinks losing their schools is like a cancer creeping through town.

Data compiled by the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) in 1987 and again in 1999 show the reality behind residents’ worries about school closings. Although school consolidation had been taking place for more than half a century, during these twelve years the number of schools in small towns fell from approximately 18,000 to approximately 11,000, and in rural areas from about 19,000 to approximately 16,000. During the same period, total enrollment at schools in small towns fell from 9.5 to 4.8 million, and in rural areas from 6.7 to 4.7 million.8

Figure 4.1 Decline in schools and enrollment

Meanwhile, the school-age population grew more rapidly in cities and suburbs than in small towns and rural areas, which meant that the nation’s schools included a declining share of these smaller communities. As shown in figure 4.1, the proportion of US schools located in small towns fell from 22 percent in 1987 to 10 percent in 1999 and in rural areas from 15 to 10 percent. School enrollment as a proportion of total US enrollment declined in small towns from 24 percent in 1987 to 13 percent in 1999 and in rural areas from 25 to 19 percent during the same period.

If school-age population was any indication, there was a good chance of small towns losing a school or already having lost one. Among all nonurban towns with fewer than twenty-five thousand residents in 1980, 81 percent had fewer than five hundred school-age children, 70 percent had fewer than three hundred, and 37 percent had fewer than a hundred. Most of the towns with small numbers of school-age children had total populations of under two thousand, but among towns with populations between two and five thousand, 27 percent had fewer than five hundred school-age children, and that proportion rose to 34 percent over the next two decades.9

It is difficult for an outsider to truly appreciate what having a school means to a small town—or the effect of losing one. In one of the mining towns we studied, there were two school buildings now vacant because the children were being bused to a town ten miles away. The buildings were crumbling hulls, waiting against hope ever to be reopened. They were a constant reminder, one of the residents explained, of better days. The silence was too. Residents remembered when children’s laughter from the playground could be heard throughout the town. They recalled children riding their bicycles and walking to school. Now the town was quiet.10

We talked with people in another town where the school had recently closed because of consolidation. “It’s an ugly, ugly thing,” a resident told us, referring to the merger process. “When the school leaves, it just sucks the life out of the town.” In another town that had lost its school more than a decade ago a man told us, “It was just like they took the heart out of our town when they did that. People no longer had a regular place to go.” He still blames the school superintendent for not fighting harder to keep the school open. “It was just a smoke job,” the disgruntled interviewee said. “They spent more money closing the school than keeping it open. That’s really when the town started going downhill.”

Teachers and many parents talk with pride about how good the school in their town is, frequently lauding its graduation rate and the standardized scores of its pupils. But the most publicized community-wide aspect of the school is usually its sports program. If the town has a local newspaper, at least a quarter of it is generally devoted to the week’s athletic events. A good student who performs well academically may get their name in the newspaper once a year, but a star athlete receives regular publicity. If the home team has a winning season, the entire community turns out for its games. Towns in rural areas typically have a highway sign at their edge stating the most recent year of winning a state championship. “I’ve said for years that the only identity small communities have is through their children,” an older man in a town of seventy-five hundred explained, referring to the importance of football and basketball tournaments. Communities just lose their entire identity, he said, when the school closes. Another resident told us, “There’s a huge sense of pride, and it kind of brings the community together when we win a basketball championship.” But he said the town’s football team was known as the worst one in the region and had been for fifteen years. “It really makes the community feel bad during football season,” he lamented.11

Because of the symbolic importance of schools to the community, coaches and teachers occupy a special position that can work to their benefit in gaining friends as well as respect, but can also make them uncomfortable when the spotlight shines too brightly. A winning coach is likely to be the toast of the town. In one community we studied, for example, the coach was especially beloved for having won several state championships. There was even a street named in his honor. Teachers and school principals we talked to usually said they knew a lot of people in town and enjoyed being in a friendly community. But that was different for those teachers who had lived in the community a long time than it was for the newcomers. The old-timers were often women who had grown up in the area or had married local men. They had family ties in town as well as professional connections. The newcomers found it harder to assimilate. They had been raised elsewhere, gone to college in a larger community, and come to town because of a job opening. Some purposely isolated themselves because they had family and friends elsewhere, and expected to move on after a few years. “They are sort of a lost group if they don’t have a family connection here,” one parent noted of the teachers in his community. “They just sort of do their own thing. They’re in the background and very quiet.” Even the ones who tried to assimilate sometimes acknowledged that it was difficult to feel accepted. They knew community spirit revolved around the school, and yet it did not always include them personally.

Some of these towns had distinctive school traditions that went back many years, but in other towns we learned of new efforts being made to invent activities that townspeople hoped would eventually become traditions. One idea is fall homecoming, which typically is the same weekend as the traditional homecoming football game at the high school, but is now a more extensive celebration that lasts the entire weekend and is billed as a town homecoming. If the town still has a newspaper, a sufficient number of former residents may subscribe, so announcements of the town homecoming can be circulated this way. Increasingly, Web sites, list serves, and emails are also used to spread the word. The homecoming festival may include a sidewalk sale, community picnic, parade, and antique show as well as class reunions and family gatherings. “People come back from all over the country,” one resident notes. “The town homecoming is a big deal,” reports another.

SMALL-TOWN FESTIVALS

One of the most popular events in small towns is an annual festival, usually held in conjunction with the homecoming weekend, or at another time when residents and former residents gather to promote community spirit plus remind themselves of the community’s traditions. These events are seldom evident in towns of fewer than a thousand residents, but were nearly universal in the towns we studied that had populations of at least two thousand. Fall harvest celebrations, county festivals, and rodeos are common examples. In most instances the festival celebrates something distinctive about the community, whether that consists of commemorating its founding or drawing visitors from the region because of its ethnic traditions. The Oktoberfest in a prairie town of twenty-three hundred surrounded by pastures and soybean fields is typical. Timed to coincide with the homecoming football game, the festival runs for three days, involves costumes and prizes, includes a dance, and reminds everyone of the community’s heritage. Another town calls its festival Old Home Week. Still another has an annual Blueberry Festival, and yet another hosts the best-attended Salmon Festival in its vicinity. Less typical is another town that celebrates its religious heritage with a festival topped by a parade of citizens dressed as biblical characters. One town we visited called itself the German capital of its state, another Little Sweden, another was known as the nylon capital of the world, and yet another billed itself as the start of the Chisholm Trail. Each had festivals commemorating its heritage. A dinner theater with special performances during the annual festival was the regional attraction in one town, an annual outdoor musical concert in another one, and a tractor pull in still another. Other festivals included Daniel Boone Day, Fun Day, Dogwood Day, Hot Dog Day, Frog Leg Day, Tomato Day, Carrot Day, and Daisy the Cow Day.12

Residents spoke glowingly of these events. The people we talked to in one small town boasted of having the best Mardi Gras festival anywhere—that is, anywhere that celebrates Mardi Gras in the fall. A leader in another community said his town was the inspiration for the famous American Gothic painting. Indeed, nearly every community in which we conducted interviews considered itself special in some way. One town conceived of itself as the birthplace of rock and roll, and another—two, in fact—as the birthplace of the blues. Yet another boasted of being the real home of the first rodeo (in contrast to faux competitors), and another as the location of the first Red Cross chapter.

In other towns, residents reported with pride that their community currently produced more irrigation sprinklers than any other place, that theirs had shipped the most ammunition during World War II, and that their town was where the police had spotted a UFO some years back. They knew about these distinctive features of their town because of hearing about them at the annual festival. A community nestled along a winding river billed itself as the best hiking spot around, a community near a lake claimed to have the best birdwatching anywhere, and another one claimed to be near the most scenic covered bridges. It may only have been that the town had the oldest Halloween parade on record, the largest ball of twine, the most colorful ceramic jack rabbits, the largest tomato ever grown, an exceptionally large oil storage tank, or the best attended gun show, but residents knew about and made a point of mentioning it, half in jest, half seriously.

Profile: Shepherdstown, West Virginia

Shepherdstown, West Virginia, is a community of eight hundred, not counting the four hundred students who attend Shepherd University, located on the Potomac River seventy-five miles upstream from the nation’s capital. Its location as well as the university has given it the opportunity to become a popular weekend getaway for visitors interested in the arts, music, and history. With Harpers Ferry just twelve miles to the south and the Antietam National Battlefield across the river three miles east, Shepherdstown has little difficulty attracting visitors, but does find it necessary to put on special events that draw them specifically.

Unlike towns that have one festival during the year, Shepherdstown has five. Each July it hosts the Contemporary American Theater Festival. In October its calendar includes the Sotto Voce Poetry Festival. And in November the American Conservation Film Festival comes to town. The theater festival is held at the university and venues in town. The film festival is also held at the university and the Opera House. In addition, the Mountain Heritage Arts and Crafts Festival is held each June and again in September. Each of these events attracts hundreds of tourists for an afternoon, evening, or longer.

Smaller events include the Back Alley Garden Tour and Tea, held each year in May, and the Shenandoah-Potomac House and Garden Tour, usually in late April.

As if these were not enough, the town hosts community-wide celebrations on holidays as well. Santa’s arrival and the lighting of the town Christmas tree occur in late November and December. The Easter bunny oversees an Easter egg hunt each spring. May Day includes a parade and traditional dance around the maypole. And July 4 includes a parade and community picnic.

These events have worked well to bring revenue to Shepherdstown, but residents worry that the community may have grown too dependent on hosting tourists. Most of the regular retail business is now located in Martinsburg and Hagerstown. A small but growing number of residents commute to jobs in Washington, DC, spending little time in Shepherdstown except on weekends. As a result, housing prices have increased. Some residents complain that the community is becoming “yuppified.” Others enjoy the festivals that clog the town with swarms of people and block the streets from week to week, but say it is harder to get acquainted and feel that people really care about the community.

If there was any way to weave its distinctive historic identity into an annual celebration of some kind, residents did so. Several towns hosted annual reenactments of Revolutionary or Civil War battles, and a few commemorated local skirmishes with outlaws and renegades. One town took pride in calling itself the Indian or, more recently, Native American capital of its region. It was true that Indians populated the region before white settlers came. But that was more than a century ago. There had been no significant Indian population in the town for many decades. Yet the town had been named for an Indian chief, and so over the years all the streets were given Indian names as well. Each year on a Saturday in May the town hosts a well-publicized Indian festival. A high school boy is elected chief, and a high school girl is elected princess. The two dress in Indian garb and preside over the event. It is all done lightheartedly, but residents say it is the one thing that gives their town an identity.

A community leader in another town agreed that something like this was important enough that a festival just might save a dying town. “The only way you’re going to survive is to make the community unique, different, even odd,” he observed. “Make it an antique capital. Restore the old opera house. Offer the best fried chicken. Have an Oktoberfest.” That view was generally shared, although occasionally we heard mixed opinions. These came from town leaders who worried that festivals were taking the place of more serious discussions about their community’s future. It was good that the festivals were happening, they said, because organizing them brought people together and sparked conversations about the town’s history. But coming up with a comprehensive plan for the future, including something about historical preservation along with applying for grants or raising money locally were much more difficult. As one town manager noted, “Those are great things to talk about, and everybody feels good doing it, but implementing things becomes very hard.”

Small-town festivals are largely organized and staffed by local volunteers, which means that the meetings during the year at which planning occurs provide occasions for sharing information about other community developments and exchanging gossip with neighbors. As is true of other aspects of small-town life, festivals are changing as a result of demographic shifts and different means of communication. The towns we studied with declining populations were finding it more difficult to organize festivals, but other communities were attracting visitors by advertising on the Internet and in state tourism magazines, and were supplementing local traditions by hosting antique car displays, tractor pulls, and craft fairs. Small towns are also benefiting from regional celebrations in which they can participate, such as festivals that combine events up and down a river, or commemorations of an early expedition or along a pioneer trail.13

At their best, festivals spark community spirit because emotions run differently than on other days, and because people physically come together and participate in common activities. The lightheartedness plays an important role. Men sport top hats and beards, and women don prairie dresses or wear Victorian-era jewelry. Children wear costumes, much like they would in any community on Halloween. The difference is that the town is symbolized as the focus of the event. Beneath the fun is a layer of serious commemoration. These are our war heroes, first settlers, volunteer fire company, teachers, or youths.14

Just as national holidays do, small-town festivals provide opportunities to define and redefine the community. In emphasizing the town’s first settlers and early citizens, residents who have lived there for generations can imagine that the community especially values its old-timers—and perhaps feel that it should pay more attention to preserving its past. Festivals also serve as occasions for assimilating new citizens. In our research, we saw this especially in towns with large numbers of recent immigrants. On the one hand, old settlers’ picnics and pioneer days permitted one definition of the community to be remembered. On the other hand, Cinco de Mayo festivals, celebrations of Mexican Independence Day, performances by Mexican American dancers and Guatemalan marimba groups, and tables with eastern European and South Asian food suggested a changing definition of the community.15

For better or worse, community festivals selectively emphasize some aspects of reality and neglect others. Just as weddings and funerals do in families, they present the community in its most favorable light. Acrimony is temporarily set aside. Festivals are not the time to worry that the town’s population is diminishing or be reminded that growth is significantly altering its ethnic composition. Whole sections of the community—minorities, the poor, and newcomers—may be left out. Celebrations work because they are clearly demarcated from everyday life. They punctuate time with levity, lifting spirits above the ordinary humdrum, adding color, drawing people loosely together, and perhaps most important, giving them something to talk about. This is why festivals so often commemorate the town’s history. In collective memory, the festivals both retell and become part of that history.

The one caveat that emerged from talking with residents is that community festivals sometimes become so popular that they overwhelm the town—and indeed define it in unanticipated ways. The clearest example was a town of two thousand that decided a few years ago to host an annual motorcycle rally. As publicity spread, the crowd grew to nearly twenty thousand bikers, biker babes, and spectators. Residents said the event was mostly helping local liquor dealers. It put the community on the map, so to speak, but not in the way many of its citizens wanted.

OF TRAGEDIES AND CARE

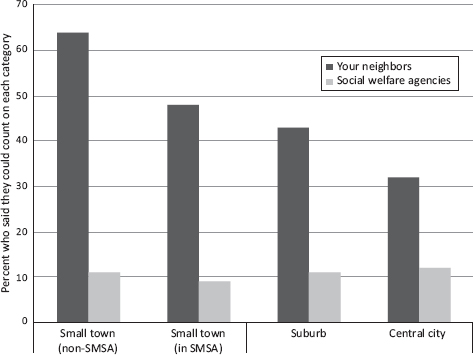

Caring behavior serves in much the same way that festivals do—when they work well—as symbols of community spirit. Residents of small towns feel that they can rely on one another for help in the event of a tragedy or some other adverse situation. In my Civic Involvement Survey, nearly two-thirds of the respondents in small nonmetropolitan towns said they could count on their neighbors if someone in their immediate family became seriously ill. That was twice the number who felt that way in central cities, and was significantly higher even than in suburbs and small towns in metropolitan areas. It was five times the number in any community who felt they could count on social welfare agencies for help (see figure 4.2).

This sense of being able to depend on one’s neighbors is what sociologist Robert J. Sampson identifies as the source of collective efficacy in a community. When neighbors trust one another and experience a sense of cohesion that involves solidarity and shared values, they also feel more capable, Sampson argues, of controlling their lives as well as facing the challenges that confront them. In his research on inner-city neighborhoods in Chicago, Sampson found that collective efficacy was strongly associated with lower crime rates and lower fears of violence.16

Figure 4.2 Who you could count on

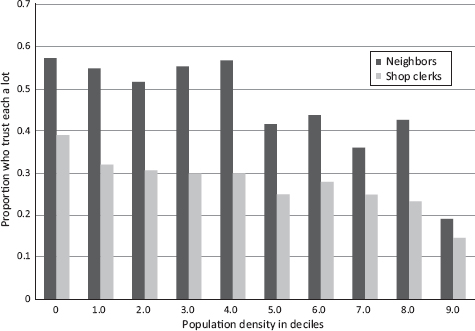

Figure 4.3 Trust of neighbors and shop clerks

Collective efficacy crucially means being able to rely on informal networks rather than impersonal bureaucratic agencies. But it does not stop there. It also means feeling more confident about the business transactions that make up such a significant share of our social interaction. Some interesting evidence of this is shown in figure 4.3, which summarizes results from a national survey conducted by political scientist Robert Putnam. Although the data that were released for public use did not permit an exact comparison of residents in small and larger towns, it did report variations in the population density of the communities in which respondents lived, which as we saw in the last chapter are significantly lower in small towns than in larger communities. As population density increases, the proportion of residents who say they trust their neighbors “a lot” declines—from almost 60 percent in the least densely populated areas to less than 20 percent in the most densely populated ones. The proportion of people who say the same about shop clerks is lower in all comparisons, but also declines significantly, from almost 40 percent down to about 15 percent.17

In our interviews, it was the fact that shop clerks and local business proprietors were known personally that resulted in their being trusted. Fellow residents knew them by name and saw them in other settings, such as at school functions, church, or civic events. This, as much as the sheer inconvenience of having to drive to another town to shop, was one of the reasons residents mourned when a local business closed. Their sense of efficacy was stronger when they could do business with someone local who they could trust.

Further emphasizing the importance of collective efficacy, a longitudinal study conducted among residents of nearly a hundred small towns in Iowa examined the extent to which shocks to the community, such as natural disasters and the loss of a major employer, affected community life. Contrary to expectations suggested in some of the social science literature, the study showed that shocks were not associated with declines in residents’ perceived quality of life. The reason possibly was the sense of collective efficacy that came from townspeople’s feeling of being cared for by their fellow citizens. What the study did not examine is how significantly caring behavior in response to local misfortune and tragedies—small and large—figures into residents’ understandings of their communities.18 It may be that these stories of caring—the narratives residents tell about how they helped one another and overcame adversity—develop within days or weeks after a tragedy, such as a destructive tornado or flood, and play a significant role in residents’ sense that their town is a good place to live after all.

When asked what is good about their towns, residents characteristically tell stories that illustrate how the townspeople work together—often in modest and yet meaningful ways—to help one another and promote the good of the community, especially during times of personal hardship. As a small example, an elderly woman in a town of two thousand recalls, “I had a backyard with a wooden fence and it was getting in bad shape, and the local men came up and tore all that out and rebuilt the fence, labor free. They didn’t expect anything.” A neighbor of hers chimes in, “I know a young couple that was expecting a child and were trying to remodel their house and get it back together and some men went up there and helped them do that, again as a charitable donation. They didn’t take any payment or anything of that nature.” One of their friends was not to be outdone. “The other day I had a vehicle that wouldn’t start,” she said, “and I just called the neighbor down the road and said, ‘Can you come over and pull it so we can get it off the street?’ ‘Sure, I’ll be right over.’ ”

Mr. Parsons and his wife tell the following story. They were at the little league game only a few weeks before we talked to them. A tornado struck a farm not far from town that evening. They called the lady whose farm had been damaged the next day and offered to bring some food. The lady said townspeople had already brought her more food than she could eat in a month. “That’s just what happens in these small towns,” he observes. “Everybody will do what they can to help out. It’s just the way we do things. That’s the way we live.”

Another man told us about his son, now seventeen, who was diagnosed with lymphoma at the age of eight. “This town did things for us that I cannot to this day believe. I mean they did fund-raisers for us in the community to help with our medical expenses. They set up special funds for us and just bent over backward for us. I would walk into a barbershop downtown and say, ‘I need a haircut,’ and the stylist would look at me and say, ‘I’ve been wanting to do something for your family to help you through this time; this is on me.’ That kind of thing is just absolutely common.”

In a manufacturing town of six thousand on a major river, residents’ minds turned to instances of flooding when asked what was distinctive about their community. “Being a river town, we’ve had flooding,” one resident explained. He recalled a flood when he was in high school. Everyone pitched in to sandbag the power plant. “There were hundreds of people helping fill sandbags. You’d look up, and somebody was bringing cold water or bringing sandwiches and potato chips or cookies. That went on for days. It’s your neighbors helping your neighbors.” Flooding like that happened about once each decade, but for this man the community pulling together during emergencies was testimony to the town’s basic virtue. “It’s the Golden Rule. That’s just the way our community is. At the drop of a hat, they’ll come and help you.”

Other examples include the story of a man who operated a greenhouse, in which he grew flowers and vegetables. When he was in the hospital after an automobile accident, the football team came over and planted his tomatoes, and some church ladies potted his flowers for him. A woman in another town says she and her husband keep several cows in a pasture a few miles away. Every so often a neighbor calls. “Your cows are out. I tried to put them in, but didn’t quite get it done. We got several of them.” She is grateful for the neighborly assistance.

Stories like this function in public discourse as warrants—supportive evidence that sticks in residents’ minds as proof that the people in their community are good caring individuals, and that the town somehow attracts and encourages such behavior. Such stories do not prove statistically that small towns are any more caring than larger communities or that residents necessarily feel better about their towns when caring occurs. They are best understood as community lore. When residents talk about their towns, these anecdotes are what they associate with the meaning of community.19

Why do small towns die? Fifty-two percent of nonurban towns of under 25,000 had fewer residents in 2010 than in 2000. But decline is seldom dramatic or fatal. Only a fifth declined by more than 10 percent, and out of more than 16,000 only 57 declined by more than 50 percent.

Sometimes death is precipitated by a plant closing or decline in farming. That happened in Lily, South Dakota, when the railroad that had led to its founding in 1898 shut down service in 1979. Lily’s population dropped from 37 residents in 1980 to only 4 in 2010.

Towns also die from natural disasters. Church’s Ferry, North Dakota, fell from 138 residents in 1980 to only 12 in 2010 when a series of wet seasons increased the size of nearby Devils Lake. McMullen, Alabama’s all-black population of 66, fled from Hurricane Katrina in 2005 and only 10 people returned.

The story of Picher, Oklahoma, was different. Located in the far northeast corner of the state, Picher was founded in 1913 when lead and zinc were discovered in the area. As mining boomed, its population grew to 14,252 in 1926. With a gradual reduction of mining in the area, the population eroded steadily, from 7,773 in 1930 to 2,180 in 1980. In 2000, the town was still doing reasonably well with a population of 1,640, and as recently as 2007 was estimated to have approximately 1,600 residents. But three years later the number had fallen to only 20. Mining took away what it had previously provided in jobs for its employees and profits for its owners. The residents who remained in Picher after most of the mining activity ended in 1967 were living amid 14,000 abandoned mine shafts, 70 million tons of mine tailings, and 36 million tons of contaminated sludge. In 2006, plans were finally made to evacuate the town, but before they could be carried out, a tornado struck the area in 2008, causing extensive damage to what remained. In 2009, the school and post office closed, and with federal assistance the remaining residents moved away.

Although the Picher story was extreme, it was not unique. Dependent on single industries for employment and with meager political clout, towns have died from mining disasters, chemical spills, and toxic-waste pollution like the one that led to Picher’s demise.

To make the contrast vivid, residents also tell stories about city life suggesting that a caring spirit is lacking there. The woman who talked about her cows above, for example, says her daughter lives in Washington, DC, where “it’s hard to even know who is in your apartment complex.” Ms. Clarke, the county extension agent, notes that she was riding her bicycle in a city a few years ago and took a spill. “I went head over heels over the handle bars, and the only person who checked on me, even though there were four people walking within visual sight of me, was the person I was with. Whereas here, if I were to have a bicycle accident and there were four people there, I really feel they would immediately try to help. There just is kind of an interest in that.”

Residents of large metropolitan communities sometimes are in fact less sure that acts of kindness characterize where they live. The comment of a man who himself does volunteer work at the Salvation Army in a city is revealing in this regard. He says that “we like to think that we help one another” in this community, but is unsure if that is true. “In my dream world, I would say yes, but in reality, who knows?” Who knows indeed; the implication is not so much that the community is uncaring but rather that people live anonymously. Nobody would know if people were or were not helping one another.

The strangest story of small-town caring we heard was told by a man who lived on the edge of town near a wooded field. He and his neighbor were digging a hole one day to put up a fence. A big rabbit came along and sat within about five feet of the two men. When they looked at it, the rabbit ran away a few feet and then returned. The men thought maybe the rabbit was sick or even rabid. But when the strange behavior continued, the men followed the rabbit into the brush and after about a hundred yards came to the rabbit’s nest. A big snake was threatening the rabbit’s babies. Clearly, the rabbit was seeking the men’s help, the speaker concluded. He said he came home and told his wife the story—and it was probably a story he had told many times. What made it unusual was that he volunteered the tale in response to a question about possible criticisms of his community. He said there had been a newcomer who had nothing good to say about the town, but after a few months she was sold on it because everyone was so caring. He thought the story of the rabbit revealed just how caring the community was. Even the animals knew it.

If caring behavior is grist for apocryphal stories, it nevertheless reinforces community spirit in tangible ways. Besides the obvious benefits of people working together to solve their problems, charitable activities promote conformity to community norms. In an interesting study of a small isolated town in northern California, sociologist Jennifer Sherman found that low-income residents who otherwise had few opportunities for economic advancement were extensively engaged in informal caring activities, such as caring for one another’s children and helping neighbors with home repair. These activities supplemented other survival strategies, such as hunting and fishing, applying for food stamps, and in a few cases selling drugs. But they also served, Sherman argued, as a kind of moral capital. By engaging in charitable behavior, poor residents demonstrated that they were responsible members of the community.20

That sense of moral capital was evident in my interviews as well. Lower-income residents distanced themselves from riffraff and welfare chiselers by describing small acts of neighborliness in which they had engaged as well as telling stories about similar activities among fellow residents they admired. Besides living frugally and keeping up their property, they tried to be good citizens by keeping their eye on an elderly neighbor, taking a Jello salad or casserole to a bereaved family, or fixing a broken shutter on a widow’s house. Neighbors who noted these activities concluded that the town was community minded.

Nor was it only lower-income residents who earned moral capital in these ways. Many of the tales of neighborly caring that people portrayed in interviews occurred among middle-class residents. The events were sometimes minor enough to seem trivial. For instance, Mr. Segundo, the man who recalled his conversations at the nursing home with Don Pedro, described his neighbor, Johnny, on one occasion helping him chop down a tree, and on another occasion, spoke of the local hardware dealer coming over in the middle of the night to help install a new water heater. These acts of neighborliness were ones that Mr. Segundo could easily have paid for—and he did in fact offer to pay. Had he lived in a large metropolitan area, he likely would have hired someone to do the work. But in a small community, where even the nearest McDonald’s was fifty miles away, neighbors depended on one another. It was how they got to the doctor in the absence of public transportation. It was where they got hamburger buns when none could be had at the grocery store.

THE UNWRITTEN CODE OF BEING A GOOD NEIGHBOR

Charitable acts, such as helping an elderly neighbor or pitching in to save the town from flooding, stand out as symbols of community spirit. They become the stock of local lore; they are part of the stories repeated at the coffee shop or related to strangers to show that small towns are good places to live. In more subtle ways, community spirit in small towns is maintained through behavior so common that hardly anyone notices it unless someone fails to conform or a social scientist comes along asking questions about it. These small acts of neighborliness convey implicitly that small towns are friendly places.

The most important rule of being a good neighbor is to abide by the etiquette that demonstrates in token ways that the town is a caring community. A key part of this etiquette is the rules that govern ordinary sidewalk behavior. There is a good chance of knowing people you meet on the sidewalk, so the proper thing is to acknowledge their presence. That can be done simply by making eye contact, but is more likely to require a visible or verbal greeting as well as perhaps a brief conversation—as one man emphasized by mentioning that he typically has at least five conversations on the way to the post office. Anything less would be rude. Not speaking or looking away is enough to mark a person as a stranger, and probably a shifty-eyed one at that. “I almost wondered if people had something wrong with their hands,” one newcomer jokes, “because every time I met someone on the street, it seemed like their hand automatically waved.”21

It is not only necessary to wave; it is incumbent on townspeople to signal in just the appropriate manner, as determined by the time of day, how well the parties know each other, and whether they are related by blood. If their meeting occurs while driving, the appropriate wave is further determined by the speed at which they are traveling, whether the greeting happens in town or the country, and how rough or smooth the road may be. For instance, a one- or two-fingered wave with palm resting firmly on the steering wheel may be appropriate at higher speeds, while an arm out the window wave at slower speeds may indicate a moment to stop entirely for a brief chat.22

Sidewalk and other public encounters are also the time to mention some piece of information that shows a behind-the-scenes connection. “You don’t just say, ‘Hi, how are you?’ ” a lifelong resident of a small town explains. “You say, ‘So, I understand your daughter broke her leg. Is there anything we can do to help?’ ” That kind of remark shows that people have been talking. It says, in effect, that even in this era of health information privacy rules, your friends know something about your family. I know this because my friends know your friends.23

Perhaps because the likelihood of knowing someone on the street is high, the custom of smiling and waving extends to strangers as well. Mr. Segundo, for example, says his son-in-law who visits from another state has remarked on more than one occasion, “People wave at me and I don’t even know them.” Mr. Segundo laughs. “Yes, that’s the way it is.” It is not that townspeople are unable to distinguish a stranger from someone they know. Rather, it is that their sense of community necessitates waving at everyone.

Another rule is to send greeting cards on birthdays, anniversaries, and holidays, and shower a sick neighbor with get-well cards and a bereaved family with cards of condolence. Card sending is expected even when townspeople routinely see each other in person. An elderly man reports with pride in his voice that his wife is “very, very good about sending out cards even to people who are pretty well outside the perimeter of knowing them but are in the community.” An older woman says she keeps a large supply of cards on hand for every occasion in case something happens when she cannot get to the store. Younger people say sending greeting cards is not nearly as common among their generation as the practice is among older people. But one young woman mentions that her mother constantly reminds her to send greeting cards. “The idea,” her mother explains to her, “is that as you get older, you plan to send out more cards than you receive.” In this instance, even though the younger woman says local customs are changing, there is intergenerational pressure to keep the old ways alive.

Beyond the simple etiquette of greeting one another properly and sending cards, the most important rule for being a good neighbor is to not be a burden on the community. In the first instance, this means being independent and self-sufficient. In fact, a kind of paradox is involved. Being a good neighbor means not depending on your neighbors for much of anything unless you are truly in desperate straits. At one of the home gatherings we convened, we asked people to say what was distinctive about living in a small town. “Less tolerant of riffraff,” one person in the group volunteered. She explained, “A small town is made up of a lot of very independent people. They don’t suffer well those who just lay around and expect someone else to take care of them.” What she was pointing to is a key principle of community life. If a town prides itself on caring for its own, that can only work to the extent that the caretaking required is limited. And the way to limit those needs is by everyone doing as much as they can for themselves.24

Social scientists would call this emphasis on self-sufficiency a way of dealing with the free rider problem—taking and not giving back. Norms have to be established to discourage free riding. Formal organizations can deny benefits to anyone who is not officially a member. In colonial America, towns would literally deport an indigent who was not an official resident. The current practice in small towns is less formal. Free riding is discouraged by calling a lazy person riffraff. “We don’t approve of riffraff who just don’t want to help themselves and who expect a handout,” this woman comments.25

Judy Quandt was a single mother with three children and only a high school degree when she moved to a town of five thousand that was suffering from high unemployment after the only manufacturing plant in the area closed its doors. She was hardly riffraff but experienced the norms that operate when residents fear someone may be expecting to benefit from the community’s generosity. She secured a cheap rental house and found a job as a nurse’s aide, yet soon began hearing rumors that she was not the kind of resident the community wanted. That was five years ago. She is now married and has found a better job. She likes living here because the rent is cheap, she can walk to work, and it is a safe community for her children. But she mostly keeps to herself. It has been hard to avoid feeling ostracized.

Being self-sufficient is such a critical part of being a good neighbor that a number of people we talked to report not having sought help at times when they could have used it. Or they tell stories about neighbors who refuse help because these extreme examples show that people really are expected to be as independent as possible. One case is Old Chuck, as he is known in the community, a retired widower who lost his house and everything in it when a forest fire swept through the area. The man telling the story belongs to a civic group that raised five hundred dollars to help Old Chuck. “Took the money to him. He turned around and handed it right back. Said, ‘I’ve never taken anything from anybody my whole life, and I’m not going to start now. Give it to somebody who really needs it.’ ”

Being reluctant to take charity is part of the code that governs behavior among recipients. To spare them the potential embarrassment of accepting charity, the matching rule is for donors, if at all possible, to give anonymously. A woman in a town of about a thousand recalled her husband falling from a roof, shattering his heel, and being out of work for months while the doctors did reconstructive surgery. “I got anonymous cash in the mail,” she says. “People would just put cash in an envelope and send it to me.” The same woman voices the discomfort that arises when charity is not anonymous. One of her daughters had recently been married. The church wedding included four hundred guests. The woman said a friend at her church who lives in a big house and is married to a banker put on a beautiful bridal shower plus provided the decorations for the wedding. That was a nice example of small-town caring, the woman reported. But as soon as she said it, her voice trailed off with something about not being financially well off. “You don’t want to feel like you’re a welfare case,” she said.

Her story is similar to an event that a woman in another town describes. “It was when the kids were little,” she recalls. She and her husband were working, but the family budget was so tight that there was no money to buy the children Christmas presents. They told the children not to say anything, but word got out at school. On Christmas Eve, they all went to the Christmas program at the school. When they came home, they found a box on the kitchen table. In it was a gift for each member of the family and an envelope with eighty dollars. “We never knew who brought it,” the woman says. She also admits that it hurt her pride to have been the recipient of charity. It helped that the charity was anonymous.

But if charity has to be anonymous, how does that affect personal relations in situations where a neighbor cannot hide their need? One possibility is that donations of time need to be handled as delicately as monetary assistance, but in a different way. Social scientists who study the meanings of money argue that financial transactions invoke special rules that usually do not apply in other relationships.26 A cash handout has to be anonymous because it would otherwise communicate to the recipient that the donor knows something about their financial situation. Talking about personal finances is generally a taboo topic, perhaps especially in small towns.27 But donations of time are different. Although hours and minutes can be translated into dollars and cents, as anyone who has dealt with lawyers knows, contributions of time for charitable purposes are usually exempt from these implicit calculations. The reason is that charitable time is popularly regarded as a voluntary activity that occurs in a person’s leisure hours, which we commonly refer to as free time. This means that people can volunteer their time for civic organizations or help needy neighbors and be more public about it than they can in giving money.

What may be distinctive about caring behavior in small towns is that neighbors actually claim to know one another and thus find it harder to escape helping one another than would be true if they knew less about each other. In a suburb where people stay to themselves, a needy neighbor can live right next door and never receive help, whereas a situation like that would be more awkward in a small town. Women who are not gainfully employed outside the home, and who therefore are thought to have plenty of free time on their hands, are especially at risk of being called on to volunteer. We heard about this from many of the women we talked to. They felt obligated to assist with everything from school committees to caring for the sick and elderly. They enjoyed being helpful, but sometimes wished they were called on less frequently.

We caught up with Linda McKenzie, a stay-at-home mother of four children ages five to fifteen in a town of thirty-three hundred, as she was dashing from one obligation to another. She and her husband live in a nearly new brick house in one of the better neighborhoods on the edge of town. Both have college degrees. He works as a commodities trader in a larger town fifteen miles away. That morning Mrs. McKenzie had been up since five, and gotten her children dressed, fed, and off to school by eight o’clock. She had also picked up a neighbor’s boy and watched after him while his mother was having chemotherapy for breast cancer, and had driven her youngest home from preschool plus delivered flowers to a friend in her community who was sick. That afternoon she drove her children and several others home from school, hosted an after-school 4-H club meeting, and then cooked supper, and in the evening took her oldest son to tennis practice and walked her daughter down the street to visit friends. When asked what she liked best about her town, a slow pace was not something that crossed her mind. It was the caring that went on among neighbors and friends every day.

She confessed it was often difficult being a good neighbor, though. The eighty–twenty principle applied, she said. Eighty percent of the volunteer work was done by 20 percent of the people. She helped the woman with cancer by watching her son and frequently by driving her to the hospital. This had been going on for four years. Another neighbor took turns driving the woman, and still another cleaned her house. “Right now,” Mrs. McKenzie observed, “I have the friend with cancer, a friend who lost a little boy to a drowning, and several neighbors who are having financial difficulties because of losing their jobs.” She sometimes wonders what more she could possibly do. But the “outpouring of support” that people give and receive continually amazes her.

Perhaps the subtlest aspect of being a good neighbor is simply demonstrating civility whenever a person is tempted to engage in conflict or express anger. Not everyone we talked with agreed about this. Some argued that people in their town were all too willing to voice disagreements and hold grudges. Yet most agreed that it was important in their community to get along and work out differences. A resident in a town of nine hundred described a junk dealer who annoyed his neighbors by feeding stray cats. Eventually one of the neighbors persuaded the city council to pass an ordinance against this behavior. For the storyteller, this was the exception that proved the rule. For the most part, he explained, people in his town try to get along. “These are your neighbors. These are the people you work with, you go grocery shopping with, you go to the sport activities, and it’s your kids and their kid’s best friends on the field. You may disagree with each other, but on all but the rarest occasions, you’ve got to get along. And they do.”

“We just aren’t very confrontational,” is the way another resident puts it. “We learned when we were young, don’t go looking for trouble. You don’t create conflict with people unless your basic values are challenged. Most things really aren’t that important. Why make a big deal out of them?” “Yes,” another man laughs. “We’re kind of restrained. We just think, let’s suffer through this.” The editor of a small-town newspaper says it differently. In his job, it is not always possible to avoid confrontation. Readers come to him angry about a story. They think he is biased, or has given someone too much publicity and someone else not enough. He remarks half seriously that he worries sometimes about the safety of his family. The conflicts are that big. “Then you find yourself sitting next to that person at a soup supper benefit that evening,” he says. “You have to be able to set things aside. You have to have good people skills or you’ll just be miserable.”

Civility in small towns is perpetuated by the simple fact that if someone treats you with respect, you are more likely to treat them likewise. There is, however, more to it than that. The network structure of small towns is also a key factor. We asked some of the people we interviewed to say how many close friends they had and indicate how they knew their friends. Most said there were between twenty and thirty people in their community who they regarded as truly close friends. The ways in which they knew them varied—by living next door, going to the same church, participating in club activities, serving on committees, having met through business dealings, or being related to one another. These different points of intersection notwithstanding, most said that their friends also knew each other. They were members of overlapping networks and participated in mixed gatherings, such as community picnics and town meetings, rather than only in more restricted settings. This was an aspect of community life that residents understood and considered important. The fact that your friends not only know you but also know each other means that the chances of them talking about you behind your back are greatly increased. If you are rude to one friend, there is a good likelihood that your other friends will hear about it. You risk alienating more than one person. “You’re always connected with somebody” is how one person explains it. “It’s always someone’s cousin.”28

Whether people talk about you behind their backs or not, the scale of life in small towns encourages at least a facade of civility in public relationships because people know they will have to continue dealing with each other the next day and the one after that. A clear illustration of this aspect of social relationships is a story that a businessperson who lives in a town of twelve hundred tells. He runs a truck farm that manages to get along with two full-time employees besides himself during the winter, but hires two to four temporary laborers from Mexico each summer on a temporary visa program that functions with government approval. A store manager in town refused to serve the Mexicans because they could not speak English, and the manager complained to the man telling the story that he should not be hiring people from Mexico. The man said this incident made him furious. He wanted to tell off the store manager, who clearly did not understand the program through which the Mexican workers were being hired. Instead, he held his tongue. “It’s a small community,” the man explains. He sees the store manager almost every day. “I have to talk to him. So you just let it fly. Unless it’s something really important, you’re not going to push it.”

The other aspect of small-town life that affects civility is the fact that onstage and backstage behavior is different than in cities and suburbs. In those larger settings, more of life can be backstage. What happens inside your home is backstage. Even the interior of one’s automobile is backstage. People play loud music in their cars, sing along, polish their lipstick, and yell rude remarks at other drivers. In a small town, all these activities are more likely to be considered onstage. That makes for a greater sense of accountability.

But in the final analysis, the norms of civility and conviviality that govern sidewalk behavior in small towns would be inconsequential were in not for the fact that sidewalks actually exist and are used. When townspeople report that they live close enough to walk to work or the post office, it is critical not to overlook the fact that they walk. In a city or suburb, they might walk the dog, but would scarcely think of trekking on foot to the mall or work. It is, once again, the scale of small towns that matters.

Furthermore, sidewalks are by no means the only spaces in which neighborly behavior occurs. Sociologist Ray Oldenburg has coined the phrase “great good places” to describe the cafés, coffee shops, community centers, beauty parlors, drugstores, stores, bars, and corner hangouts that he believes constitute the essential fabric of community life. In these public spaces, Oldenburg argues, people share in the joy and stimulation of fellowship with respected peers. The need for sociability, he says, has encouraged such places to emerge wherever people live and congregate, whether in cocktail lounges in upscale neighborhoods, or inner-city pool halls, or at day-care centers and fitness clubs.29

On a per capita basis, small towns may have no more of these public spaces than cities do, but it is impressive that almost no town seems too small to have at least one, if not half a dozen or more, of such places. In nearly every community we studied, a VFW, American Legion, or community building provided indoor space for small community gatherings. Larger events were held in school gymnasiums and auditoriums, at fair grounds, and in churches. It was a matter of pride in some communities to have constructed a roller-skating rink or swimming pool where children, teenagers, and their parents could gather, and in others, to have an agricultural building or picnic ground that served a similar purpose. Because people knew one another or were expected to act as if they did, the post office, café, and convenience store served as public space as well.

There were specific spaces in which community issues that may have been divisive were hammered out. School board hearings and town council meetings served this purpose. But conflicts that may have been evident in those settings, or were expressed behind closed doors among relatives and in law offices, were seldom reported to have occurred in these other public spaces. They were great good places that preserved the spirit of local conviviality by keeping conversation within the accepted norms of congeniality. It would have been embarrassing to have a heated political argument in such settings and quite out of place to shout an obscenity.

THE DIFFICULTIES THAT NEWCOMERS FACE

Nearly everyone we talked to in small towns admitted that it is difficult for newcomers to feel comfortable in their towns. Even though long-term residents usually claim to want newcomers, and many towns even have programs to attract people, it seems that moving into one of these communities is not easy. A woman who herself had moved to a town of twenty-five hundred people four years ago expresses the prevailing view: “It’s a bit cliquish. If you weren’t born and raised here, you’re an outsider even though you’ve lived here for thirty-five years. That’s just kind of typical in small communities.” Ms. Clarke, the agricultural extension agent, says this was certainly true of the small town in which she had been raised. “If you didn’t grow up there, it’s very hard to commingle and truly become part of it,” she remarks. “You’re a new person for far longer than you would be a new person in a larger area.” She has been actively involved in her present community for five years and still feels like a newcomer. Long-term residents agree that they probably are not as welcoming toward newcomers as they should be. “It takes courage to get out of your comfort zone and go introduce yourself to them,” one man explains.

People who lived in towns dominated by a single ethnic or nationality background say it is especially difficult for newcomers to assimilate into their communities. Language is rarely a barrier, but ethnic distinctiveness has been maintained over the years through other means. People go to the same church and marry within their ethnic group. The old-timers who are honored at community events for having operated a business a long time or hold large family reunions at the town hall are from the dominant ethnic group. Outsiders from a different ethnic background feel the subtle ways in which food, values, and habits of deference and demeanor are unfamiliar. “It is a very closed community,” a resident who moved to a predominantly German town of two thousand two decades ago observes. “They have close-knit families here and that is who they socialize with. To really get to know people here is hard. It is very definitely a German community, and Germans have a very different way than I was used to growing up.”

What facilitates assimilation into small towns is the same thing that smoothes the transition for newcomers in cities and suburbs: children. As one man who has lived in several small towns puts it, “Kids help the most. If you have kids, there are a lot of kids’ activities and a lot of family activities. That’s very easy to work your way into.” Even people who do not have children sometimes have found that children’s activities, such as ball games or scouts, are so central to community life that these events are the best way of meeting neighbors and making friends. “You go to football games and sit by somebody on the bench,” a woman in a town of two thousand explains, “and then maybe after the game you get together.”

Civic clubs help as well. “If you really want to grab the bull by the horns,” one man advises, “join Rotary, join Kiwanis, join Lions.” That usually works best, though, for married men. Single men and women say they have found it hard to assimilate. Small-town bars are not exactly where most say they want to hang out. Without children or spouses, they feel isolated. A man I met through a mutual acquaintance and knew only as Alejandro drove this point home one day. He was telling me how much he loved living in a city of two million. “It’s a great place,” he said. “Lots of bars and stripper clubs. I go out with a different girl every weekend.” Then he told me about his cousin who lives in a small town and is unhappy. His cousin happened to live in one of the towns I had been studying. “He should move to the city,” Alejandro said. “You just need to be happy. The bars and the stripper clubs make me happy.”

Because they know it is difficult for newcomers to fit in, many of the townspeople we met volunteered advice for anyone who might be considering moving to a small town. One suggested going next door for a stick of butter or cup of sugar just as an excuse to meet neighbors. In a small town, she says, that would be something neighbors would do. Another advised watering the lawn or planting a garden at times when neighbors were out, and by all means going over to chat if someone else came along. The bottom line is that a newcomer has to plan on making 90 percent of the effort to meet people, they said. Volunteering for committee work was often mentioned as well, but newcomers themselves expressed misgivings about this strategy. They said committees were frequently governed by such strong traditions that only old-timers were allowed to serve. A newcomer who volunteered might be regarded as pushy.

Townspeople say it is hardest for newcomers from the city to fit in. The difficulty is failing to recognize and understand the subtle cues governing behavior in small towns. “If they were from a small town and they understood small-town life,” a man who headed the welcome committee in his community noted, “they would tend to fit in pretty well most of the time.” In contrast, city people seemed to come with an “attitude,” he reported. They did not know exactly when and how to be neighborly, and that somehow was interpreted by the locals as dismissive or arrogant.

Members of the welcome committee have a story they like to tell, this man says. “A guy is moving into town, he stops at the gas station and says, ‘Is this a friendly town or not?’ and the guy at the gas station says, ‘Well, what kind of town did you just come from?’ ‘Oh, it was a miserable place, the people were unfriendly, unhappy, they didn’t treat you well; it was just a terrible place to live.’ And the guy at the gas station says, ‘I’m sorry, this is exactly that kind of town.’ Another guy comes by and says, ‘What kind of town is this?’ ‘What kind of town did you come from?’ ‘Oh, greatest, friendliest people in the world, wonderful place to live, to raise your kids, couldn’t ask for anything better.’ He says, ‘Guess what, you found that town again; it is great here.’ ”

This is a comforting story for the welcome committee. The message is that whatever difficulties newcomers have adjusting are their own fault. Not only do they have to learn the unspoken rules of being a good neighbor. They also have to put themselves out. They need to show themselves willing to get involved in civic activities. “If you want to get involved,” the man telling the story explains, “then this is a great place to live.

It would be mistaken, however, to argue that newcomers are deterred principally by the treatment they receive from established residents. Small towns attract their share of people who come expecting to leave as soon as they can. We found this to be true especially among younger college-educated professionals. The smallest towns were good places to start when a teacher or health worker was fresh out of college. With no experience, new teachers were sometimes unable to secure a position in a larger school system. The small town was desperate to find a teacher. Classes were probably small and less intimidating. The teacher would come for a year or two and then move on. The same was true of health professionals, some of whom came because of loan-forgiveness programs requiring a few years in a rural community.

The clearest contrast between small towns and cities with respect to newcomers’ adjustments is that choice plays a much greater role in cities. The recurrent theme among small-town residents is that newcomers have one choice: they can choose to become part of the community or not. In cities and suburbs the emphasis is on choosing among a variety of possibilities. A woman whose daughter-in-law recently moved to a large city offered a good illustration. “She found other young moms,” the woman said. “She found people who think like she thinks, people who want to raise their kids like she does.” Generalizing from this example, the woman said the adjustments necessary were “just finding the kind of activities you like, finding the kind of friends you like, concentrating on that.” Those choices were more available in the city where her daughter-in-law lived than they would have been in a smaller community.

DEALING WITH SCORN

With the vast majority of Americans now living in cities and having done so for several generations, it is easy for small-town residents to feel ignored and even second rate, as if they missed the train somewhere along the way and are having to stay behind as a result. If they feel attached to their community, it is still easy to consider themselves inhabitants of a second-class place. Perceptions of this kind are evident in occasional remarks about the advantages of living in cities and defensive comments about residents’ decision to live in small towns. Although the sense of being looked down on by city people can be understood in psychological terms, it functions mainly as a further symbolic distinction through which community is defined. Townspeople and residents of large cities may watch the same television programs, eat the same breakfast cereal, and shop at the same chain stores, but stereotypes of the differences persist. Small towns are places where village idiots reside, country bumpkins gather, and rednecks tell bigoted jokes. In defending themselves against the negative views they assume city people hold about them, residents of small towns assert what they believe is actually of value about their communities.30

The distinction between small towns and cities manifests itself in the stories townspeople tell about city people who looked down on or did not understand them, and their own rebuttals of these negative or ignorant perceptions. A woman who lives in a small town and does not herself have much education, for example, says she has been called a redneck and her sons, who are both in college, have felt looked down on by students from urban backgrounds. A woman in a mining town seconded that observation, saying that visitors look down on the locals for being uneducated and poor. She has heard comments about residents dressing poorly, not carrying themselves properly, and burping too loud. Another woman who is well educated and grew up in a small rural town says her current friends in the city ask if her hometown has electricity, and figure everyone there is a racist or right-wing fanatic. A businessperson in a town of about a thousand who deals with customers and suppliers from cities notes that a common response from these city people seems to be, “I’ve got this guy out in the prairie, a country bumpkin,” who they can take advantage of. “They don’t realize that, gee, we do have telephones here.” In a town that attracts tourists from cities because it is near a national park, a resident says she has gotten used to strange remarks from city people. “I’ll greet them, and they will slow their speech down and raise their voices, and say, ‘Do you have a bathroom?’ ” Sometimes city people ask her how a literate person can live in a small town like hers.

But the comments people in small towns remember from city folks more often are interpreted by the townspeople as reflections of urban ignorance than of scorn. City people likely have not heard of their town, sometimes even have no idea where the state is located, confuse it with another state, and ask if it is like something they have seen in a movie. One resident recalls being asked if her town has the Internet. She thinks it funny that anyone in a city would think her town of less than a thousand does not have the Internet.