Going to Be Buried Right Here

How Residents View Their Towns

“OH, WE’VE TALKED ABOUT MOVING SOMEPLACE WHERE IT’S warmer or to a larger community. But we have always said no to that. We were born here. Even our kids have stayed in the area. We’re going to be buried right here in this local cemetery and we’re very comfortable with that.” It just made sense to this man that his midwestern community of fifteen hundred was where he was meant to be—now and forever. He and his wife were the sixth generation of their families to live here.

But is that typical? Certainly it is unusual in contemporary America to find anyone whose family has lived in the same small town for six generations. Even in small towns the average length of residence is only nineteen years, and one of every five residents has currently lived in their community for fewer than five years.1 What about the typical resident who has resided in their town for only a generation or two? Or is a newcomer, or has lived elsewhere and moved back? How do they understand the choices they have made? What are their reasons for living where they do? What do their perceptions tell us about the changing meanings of community?

As I listened to people talking about their towns, I realized that many of the perceptions promulgated by television as well as in movies and books need to be examined more carefully. Some of the stereotypes about small towns are consistent with how people who live there think about their communities. They may perceive the pace of life to be slower, for example, or cherish the town because it reminds them of the warmth and security they experienced as children. But the specific attractions—and drawbacks—of small towns cannot be understood without listening closely to residents’ descriptions.

From residents’ accounts, we learn more precisely what it means when people say that the pace of life is slow. We see more clearly what counts as neighborliness, and why that is both an appealing part and a drawback of living in a small community. A person who anticipates being buried at the graveyard in their hometown is expressing something more than resignation. It is not surprising that people who have settled into a life in their community have many good things to say about that choice. And yet the firsthand remarks are surprisingly candid about what is not so desirable.

Perhaps because they fear civic loyalties are declining, social scientists have become increasingly interested in better understanding how communities function. Residents of small towns are keen observers of their communities, and frequently offer rich insights into the social relationships that strengthen—and at other times weaken—their ties with neighbors and fellow residents. We learn how networks govern what can and cannot be said, why newcomers feel uncomfortable, and what provides a sense of community spirit. To an outside observer, small towns may seem static, but a closer consideration shows how they are changing, and why some changes are welcomed more than others.

Ever present in residents’ minds are comparisons between small towns and larger places. These comparisons are replete with information about the values Americans think can better be found in small communities than in metropolitan areas, and what they feel is being lost as more and more people live in cities. Urban residents provide insightful contrasts. Age-old distinctions between country and city are still very much alive. These distinctions, though, are continually adapting to new realities. Residents of small towns worry that their communities are losing timeworn values, while residents of suburbs and cities hope their communities can retain some of what was desirable in small towns.

More than a century ago, Tönnies, the German scholar whose discussion of the distinction between the terms gemeinschaft and gesellschaft has held continuing resonance among social scientists, argued that community that transcends kinship (a community of blood) should include a meaningful combination of place and spirit. Neighborhoods, villages, and towns typically involve both. Place implies proximity, and thus mutual familiarity among coresidents as well as common interests driven by their relationship to the natural and built environment. The “rooms and cellars and their furniture,” “groups of buildings,” and “the roads and streets between them,” Tönnies wrote, provide a dwelling place that gives residents their “common habitation.” Spirit inheres in common memories and mutual understanding, a kind of tacit consensus as well as repertoire of shared values that may at times involve something akin to worship or a sense of sacredness about the collectivity of which all are members.2

Tönnies’s discussion remains a useful starting point for understanding the contemporary meanings of community in small-town America. Place and spirit are integrally connected. The fact that a small town seldom covers more than a few square miles means that residents not only live within close proximity of one another but also share a common visual horizon of natural topographic features, buildings, streets, and fields. Proximity influences time as well as space. Distances and temporal relations shrink. The spiritual connections that are forged through neighborly visits, looking after the safety of one another’s children, shopping at the same stores, and participating in community events inscribe meanings into the commonly experienced environment. It is a circumscribed space with a name and identity. To be “buried right here” literally symbolizes the deep connection between place and spirit.

And yet community, even in the smallest towns, is never realized as an entirely self-contained enclosure. Residents participate in the wider world too, commuting, visiting, and vacationing. The consciousness of living in a small town is always divided between what is here now in the present and what lies elsewhere as well as beyond. For contemporary residents at least, the meaning of community is expressed in the language of choice. What an inhabitant prefers is an indication of how community is perceived and an expression in turn of how it is valued.

THE FAMILIARITY OF CHANGELESS PLACES

Ann Gautier lives in a town of four hundred that offers a beauty salon, tavern, American Legion post, post office, and not much else. The nearest city of any size is two hours away. Mrs. Gautier runs a farm supply store and teaches school part-time in another town during the winter months, which seem to last most of the year in her part of the country. Her husband died a few years ago, and none of her children live in the area. She has been thinking lately about her mother, who also died recently. It was her mother who encouraged her to live in a small town. Small towns were just healthier, her mother always told her, because the air was fresh, and you could buy meat and vegetables from local farms.

But Mrs. Gautier’s mother also believed in seeing the world. Her mother and father traveled extensively, and on one occasion lived abroad for a year. The summer after high school Mrs. Gautier lived in Mexico and after that left her hometown for good to attend college in a city several hundred miles away. She did her practice teaching in the suburbs of a large city, and then applied far and wide for teaching jobs. There happened to be an opening in the town where she now lives. She was glad it was in a rural area where she could buy natural foods, like her mother advised, but was worried about not being accepted as a newcomer. Had it not been for meeting the man she married, she would likely have moved on.

Like Mrs. Gautier, hardly anybody we talked to indicated that they had no choice about where they lived or had never considered living elsewhere. They did acknowledge that their choices were guided by circumstances. They said they chose to live in a small town because they had enjoyed living in one as a child, felt close to their parents who still lived in a small town, had been financially dependent on their parents at some point in their adult lives, had not been successful or happy living in a city, or had married someone from a small town. Those who left the small town of their youth said they had always wanted to live in a city, liked to travel and see the world, were set on a career that required living in a larger place, had been bored growing up, did not like their classmates in school, or met and fell in love with someone from another place.

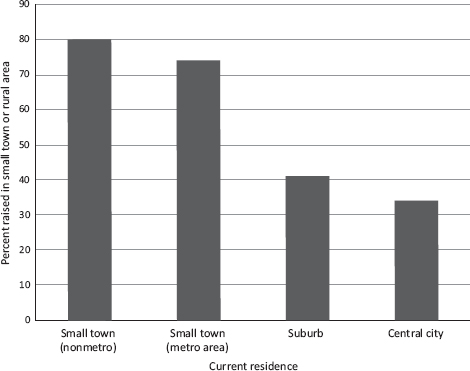

Figure 3.1 Residents raised in small town or rural area

Comments like “to be honest, I came back after college and was bored,” “I never kept in touch with any of my high school friends,” “I always wanted to move to a city,” and “my boyfriend wouldn’t have been happy here” were typical of people who had grown up in small towns and left. One woman who had moved away, for example, was particularly candid about her hometown. “It was the same twenty people I went to school with from kindergarten until high school graduation. Looking back, even as a little kid, I didn’t really have much in common with them.”

It is not surprising that influences, such as childhood experiences, family crises, marriage, and jobs, shape people’s preferences about where they live. National data show that one of the strongest determinants of where people live is where a person was raised. For example, four-fifths of the respondents in one survey who were currently living in a small nonmetropolitan town had grown up in a small town or rural area, compared with only two-fifths of those currently living in cities or suburbs (see figure 3.1).3 Although respondents may have been raised in a different town from the one in which they currently live, these data suggest that a large majority of small-town residents live where they do because of circumstances during their youth that either reduced their opportunities to live elsewhere or positively encouraged them to remain in a small community (the large minority of urban and suburban residents who grew up in small towns and rural areas is also impressive). It is important to understand, though, that the people we interviewed talked freely about such background influences, because this information puts their comments about what they like or dislike about small towns into perspective.4 The attractions are not principally the main reasons they live in a small town. Having chosen to live there because of circumstances, people point to these attractions as some of the benefits of their choice. It is, in effect, a matter of saying that one can be happy anywhere. These are the reasons to be happy in a small town.5

Small communities are often viewed by the people who live there as places that do not change much from one decade to the next. Towns may lose or gain population, but these shifts usually occur slowly. Among all nonmetropolitan towns with fewer than twenty-five thousand residents in 1980, for example, the majority were smaller three decades later, but only 18 percent lost population at a rate averaging more than 1 percent a year over the next quarter century, and only 20 percent gained population averaging more than 1 percent a year during that period.6 Unless towns happen to be located near a rapidly expanding city, or in the path of a new airport or highway, residents’ way of life is unlikely to be dramatically disrupted. For residents of rapidly growing cities and people who move around a lot, change is the spice of life. For people in small towns, just the opposite is generally the most compelling aspect of the community. They like the fact that things stay the same. As one of the town leaders we talked to noted, only half in jest: “There’s a mural in city hall that got painted in 1900. Sometimes I look at that mural and I think there are a lot of people here who would like the town to remain exactly that way, just completely unchanged.”

A case of someone who likes the changelessness of life is Mr. Parsons, the man we met in the last chapter who works at a bank in a town of six hundred and does hobby farming on the side. He says straight-out that he hates change. He would still be raising hogs on his father-in-law’s farm if he hadn’t been forced to pursue a different line of work. So living in a small town similar to the one near his childhood home has been to his liking. He enjoys tinkering with his old tractor as well as going to a little league game now and then better than traveling to someplace new. He loves the hilly wooded landscape surrounding the town. One of the best things about living here, he says, is the familiar smell of a farming community. “When they cut the hay, there’s a smell that is just unreal,” he observes. “It just gives you shivers.” He likes the smell of cattle barns, straw, fresh paint, and even fly spray and manure.

This is an extreme example, but it is not that atypical of the way many townspeople describe their communities. They like the familiar sights, sounds, and smells of where they live. “It’s the same talk, the same activities, the same festivals every year,” explains a woman in her thirties who lives in a southern town of three thousand. “Everything’s the same.” That is how she likes it. Being a “creature of habit,” “predictable,” and wanting to know what’s going to happen seems right to her.

“Oh, I’d really miss the familiar faces,” a woman in a town of sixteen hundred replies, when asked if she has ever thought about moving away. The phrase “familiar faces” seems to have special meaning to her, more so than plain words such as friends or neighbors. “I love the smell of fresh dirt around here,” a man in another small town remarks. The farms and fields give him a sense of security. Comments like “it’s pretty stable here” and “we’re not changing much” are common. Townspeople revel in the daily sameness of it all—seeing the same neighbors, living in the same house they lived in as a child, and enjoying the same landscape. “I’m looking out on a big lush green pasture with cattle grazing off in the background,” a woman says, describing the view from her front window in a town of two hundred. “The only sound I’m hearing is the air conditioner running.” Except for that, things are pretty much as they have been for two generations.

The perception that nothing ever changes in small towns is of course contradicted by the fact that things do change. Populations increase or decrease, people move away and newcomers arrive, stores close and others open. But even residents who acknowledge these changes—sometimes celebrating them and often bemoaning them—insist that they like the fact that things remain the same. What they mean is that life in a small town can be—indeed, has been for them—stable, at least compared with what they imagine city life to be. An older man who has lived all his life in a small community explains, for instance, that his brother moved to a city and made a lot of money. Yet his brother, the man says, has “traveled all over the country,” lived in a number of different places, and gotten caught up in “the rat race.” His brother’s children are “very unsettled,” he adds. They are latchkey kids. In this man’s view, it is not just that cities change more than small towns but also that getting along in a city requires people themselves to change more frequently by moving around and thus becoming unsettled—to the detriment of their families.

This emphasis on stability is illustrated in a different way in the remarks of another man, a professor who teaches at a community college in a rapidly growing suburb of a large midwestern city but who grew up in a small town. He feels that unlike many of his suburban neighbors, he has been able to lead a stable family life, pointing to thirty years of marriage as proof. He says several of his closest friends have enjoyed stable lives as well and ventures that this is probably atypical of the larger metropolitan area. He attributes this stability to the fact that “they all came from environments like I did. They weren’t real city dwellers. They were mostly from farmland backgrounds and small communities. They’re more down to earth.”

On the surface, the language townspeople use to depict the changelessness of their communities mostly suggests a sense of rootedness. Being down to earth means feeling grounded. Not traveling all over means staying in one place. Feeling settled is the opposite of being up in the air. These are the metaphors through which the attractions of being attached to a particular place are expressed. The language also emphasizes the advantages of familiarity. A person who lives in a small community knows it, and knows what to do and how to get around. That knowledge is the basis for a sense of personal security. It depends on a lack of change, but paradoxically can accommodate change to a degree. A person may never have had occasion to visit a resident on the other side of town or contact the local attorney, yet knows how to get there and probably knows someone else who has done so.

An interesting study by psychologists Walter Perrig and Walter Kintsch examined how this sense of familiarity may work. Subjects were presented with two different descriptions of a hypothetical small midwestern town called Baldwin. In one portrayal, which the psychologists called the Survey version, the town was described as it might appear on a map—for example, “The general store is on the southern end of Main Street” and “A few blocks north on Main there is the Lutheran Church on its east side.” The other description was termed the Route version, and consisted of statements such as “Going left on Main after a few blocks you see the Lutheran Church on your right” and “Returning on Main Street to the other end, you come to the general store.” Using various structured and open-ended measures, subjects’ recall of the town was tested. The main result was that subjects’ recollection was much better for the Route than for the Survey version.7

Why might this have been the case? One reason may have been that the Route version used more personal pronouns and therefore drew subjects into the picture more effectively than the other version did. The words invited them to identify with the places mentioned (“you see,” “you come to,” or “on your right”) and described what to do (“drive east,” “cross the river,” or “come to the general store”). Although the subjects had never been there and the town did not exist, they could visualize themselves being part of it.

In real life, this is also what townspeople experience and what they imply in their descriptions of what they like about their community. They not only know where the Lutheran Church is located; they have walked or driven past it, have probably been inside or talked to someone who attended there, and they know how to get there. When people spoke about the hayfield south of town or hardware store that used to be on the corner, they could visualize themselves in the picture. It was easy to recall the hardware store even if it had been gone for years or even if they no longer lived in the town. This was the meaning of familiarity. Feeling at home in a community means in the first instance being an active participant in any description of it and knowing one’s way around.

THE SLOW-PACED LIFE

Closely related to the perception that small towns offer changelessness and stability is the perception that life in small communities moves at a slower pace than anywhere else, and thus is more relaxed.8 “The slower pace is quite an advantage,” a man in a town of three hundred says. “It’s restful, less distractive.” “It’s just a relaxed way of living for people,” a shopkeeper who lives two blocks from his store in a town of a thousand remarks. Another man says he walks most mornings to the post office, which is just two blocks from his house, chats with a couple of neighbors along the way, and thinks to himself, “This is such a nice place to live.” Yet another man, who lives in a town of six thousand, muses after a recent visit to Los Angeles, “I just didn’t like the pace there. We’re more laid back. Things are slower. You can take a breath here. In the big cities, you hardly ever seem to be able to take a breath.”9

A resident of an even smaller town likewise voiced an almost-physiological response. With hardly any trees and situated on terrain flat as a pancake, the town gives her a sense of being able to see. She likes that because it helps her feel at peace with the world and herself. She says that when she lived for a few years in a city, she felt claustrophobic. “I felt like I couldn’t see anything. I didn’t know what was going on.” For her, space and time are closely connected. The city was both crowded and frenetic. She simply experiences less anxiety in a smaller place. The smells that people associate with small towns clearly have a physiological basis, too. In the same way that a person from a mill town may be reminded of home by the smell of sulfur in the air, a person like Parsons feels at home smelling cow barns and hayfields. Another man in a farming town says he loves driving past a freshly plowed field. It is the “smell of fresh ground,” he says, that sticks in his mind.10

Emphasis on a slow-paced way of life can conjure up images of lazy, slow-witted people who get up late, spend their mornings drinking coffee with friends, and then take long naps during their afternoons. A woman we talked to in a larger community, for example, expressed this view in criticizing her mother-in-law, who the woman said lived in a small town where people gathered at the coffee shop every morning at 9:00 to share gossip, continued gossiping over lunch at 11:00, and returned at 3:00 p.m. for more of the same. Survey results sometimes reinforce these impressions. For instance, 95 percent of the residents of small nonmetropolitan towns in one survey described their communities as “comfortable,” 92 percent said their communities were “quiet,” only 18 percent said their communities were “exciting,” and 38 percent admitted that their towns were “dull” and “boring.”11

Researchers, noting that people often associate small towns and rural areas with a slower-paced life, have tried to determine if life actually is slower in these places. In a classic study, psychologists Marc H. Bornstein and Helen G. Bornstein found evidence that people walk faster in large cities than they do in small towns. The reason, the psychologists suggested, is that crowding, feelings of being somehow personally restricted in one’s movements or the use of one’s time, and increased social stimulation lead to a sense of overload in larger places that people try to adapt to by walking faster.12

Among several follow-up studies, psychologists Robert V. Levine and Ara Norenzayan conducted one of the most ambitious in thirty-one countries, and included observations of pedestrian velocity and the length of time it took postal clerks to fill a standard order for stamps. Undertaken only in large cities, the study did not include an adequate test of the effects of population size, but did suggest that individualism—as measured by a subjective assessment of the local culture—might be more prevalent in larger places and seemed to be associated with a faster pace of life.13

The most extensive research on walking speed and related measures that actually compared small towns and cities in the United States was published some years ago, and was based on relatively sparse observations of approximately two hundred people in six East Coast cities and about fifty residents of small towns in the vicinity of Ames, Iowa. It showed that people, on average, walked slower in the small towns than in the cities, and that post office and gas station transactions took longer in small towns than in cities.14 While these results are suggestive, the lack of more recent research comparing residents in more towns and cities of course makes it difficult to draw broad generalizations.15

The other obvious weaknesses of these studies is that none of them asked subjects if they were aware of walking slower or conducting business transactions less rapidly than in other places, or if it mattered to them how quickly or slowly these activities occurred. There was no indication if these measures of pace were related to other possible sources of variation, such as subjects’ age or occupation, or other uses of time, such as minutes spent in traffic or relaxing over a cup of coffee. Nor was there any evidence to suggest that residents who say they prefer a slower pace of life are thinking about how quickly or slowly people in their community walk.

Thus it is important to consider what people actually mean when they talk about enjoying the less frenetic pace of small-town life. The single theme that emerges repeatedly is the convenience of living in a community free of the complexities associated with large populations. As one man explains, “We don’t have the burdens of living in a city.” Or as the man who says the slow pace is “less distractive” mentions, “You don’t have ambulances and emergency vehicles going by.” “Not a lot of congestion,” a neighbor of his adds, “not the problems you have in urban areas.” These residents are rather pleased that there is not a single stoplight in the entire county. A woman who lives in a town of twenty thousand where the population has been growing and where there are numerous stoplights offers a similar view. She has lived in a city and currently works in a high-stress managerial job, so in noting the slow-paced life as an attraction of her town, she quickly adds that she is capable of dealing with a quicker tempo. What she likes is that living close to her work, having shops and basic services nearby, and not having to fight traffic every morning and evening all supply her with more time to relax. The slow pace literally gives her the chance to stop and chat with someone on the sidewalk, or wave to a neighbor from her car, whereas she figures in a city she would be too busy negotiating bumper-to-bumper traffic.

Almost more than anything else, it is the absence of traffic in small towns that serves as a metaphor of the slow-paced life. “Oh, today was very stressful,” an old-timer in a town of six thousand likes to tell visitors from the city. “I had to wait for a car to go by before I could pull out of my driveway!” When people mention walking, it is not that a person is expected to walk slow or fast but rather that walking and not driving is possible. They may put more miles on their automobiles than someone in the city, especially if they commute from a small town to a city to work or shop. But being able to stroll down the sidewalk is a symbol of the carefree life. It means having to make fewer decisions, being less dependent on technology—“unplugged,” as one woman put it. A project can unfold over a longer period. A person can take time getting somewhere.

Townspeople like these typically associate the slow pace of life with simplicity. They view small towns as places where the basic necessities of life can be attained without the hassles of large metropolitan areas. Going to the post office is not a half-hour drive through heavy traffic and another twenty-five minutes standing in line. That is the example given by a longtime resident of a town of ten thousand. “We get spoiled by the convenience of a small town,” he observes. “We expect to drive right up to the front door and go in and be waited on immediately.” Others speak of being able to walk to work in a few minutes or living close to their children’s school. Still others mention safety, not meaning a low crime rate particularly, but instead less risk of being killed in heavy traffic on a major highway.

The common denominator in comments about the slow pace of smalltown life, familiarity of a changeless ambience, and convenience of not having to wait in long lines is being in control. Community implies a social arrangement that helps people get along with daily tasks, much like a home does, as opposed to a large-scale social space in which everything is dauntingly complex. Small towns feel right to their residents because the size of the community is relatively free of confusion. Small towns are in this respect like an extended family that takes care of its children. Mildred Ferguson, a homemaker in her fifties who has lived in several different countries and in cities as well as in small towns, puts it well when asked what she likes about her current community of six hundred. “Oh, I don’t know how to explain it,” she replies, “but you can walk down the street and you don’t have to worry about something happening.” Or as Sharon Sandler, who lives in a coal-mining town of seven thousand and travels frequently, says in describing what she dislikes about being in a city, “I feel like a little fish in a huge pond, just swimming in circles, and I don’t know what I’m doing, where I’m at, or what to do.”

BACK IN THE DAY

For people who did not grow up in a small town but who have chosen to move to one, the attraction is often that small-town life reminds them of something pleasant from childhood. Their memory is of a simpler time that no longer exists in most places yet is still present, they believe, in smaller communities. “It’s sort of like the neighborhood I grew up in the fifties,” one woman who had been raised in a middle-class suburb of a large city and who now lives in a small town explains. The neighborhood she remembers was “trusting” and “comfortable.” It seemed like a “big family.” She recalls leaving home in the morning as a child on her bicycle, playing all day with friends, and roaming the neighborhood. The small town of a thousand people where she now lives is like that. “The world is just so troubled,” she says. The small town gives her a “day-to-day haven in a very troubled world.”

Other townspeople view their communities similarly. In a town of two thousand, a newcomer in his early forties says the community takes him back thirty years to his childhood home in a town of about the same size. “I went the other day to the little mom-and-pop movie theater on the corner. I thought how quaint. I haven’t seen one of these since my childhood. It reminded me of my youth when everything was locally owned, when people were friendly and nice.”16

Besides reminding them of their childhood, small towns where people have lived for generations also provide a tangible link with the past through the presence of those family members from previous generations. These are the “ghosts of place,” as sociologist Michael Mayerfeld Bell has colorfully termed them. They inhabit the cemetery that is near enough to be visited often. The memory of their lives is tangibly associated with the field they farmed and stores where they shopped. Their presence is felt on Memorial Day and at funerals, when families gather at the cemetery where parents, grandparents, and great-grandparents are buried.17

There is more intergenerational mixing among the living as well. “We are pretty family oriented here,” a woman in her twenties says of her community. “It is not uncommon to see three-generation families in this area. People make an effort to spend time together with their grandparents, grandkids, and parents.” She comments that this is important to her because there are not a lot of people in the community her own age. She especially likes to sit with older people and hear their stories. A man in his fifties who is part of a multigenerational family echoes her sentiments. His grandfather came to town a century ago, his father still lives here, and his daughter and son-in-law do too. This is where “all my growing up memories” are, he says.

The following is another example.

“He just looked at me. He was wearing an old cowboy hat and jeans and so on. I noticed him when I was visiting my grandmother down the street at the nursing home. There was something familiar about him. I kept looking at him every time I would go. He would just be looking out the window, just staring out at the sunset. One day I said, ‘Is your name Don Pedro Milagro?’ ”

This is Ramon Segundo explaining why he would never live anywhere else. His town is an arid place of five thousand not far from the Mexican border, with barely enough moisture to keep the mesquite trees that grow along the arroyo alive. Several of the ranchers irrigate a few acres to grow hay for their livestock. Mr. Segundo, now in his sixties, works for the sheriff’s department. He has lived here his whole life.

“ ‘Is your name Don Pedro Milagro?’ I asked him a second time, thinking perhaps he was hard of hearing.

“ ‘Who wants to know?’ he replied. Of course we were talking in Spanish.

“ ‘My name is Ramon Segundo and I think I know you. You look like Don Pedro Milagro. I have a good memory of him. You used to live on Walnut Street. I used to work in the fields.’

“During the roundup season, Don Pedro was a cowboy, but during the agricultural season he used to work in the fields. He had a prestigious job because he was older. He was the person who sharpened the tools. He got paid maybe ten cents more an hour than everybody else.

“ ‘You’re him, aren’t you?’ I said.

“ ‘Yeah, but how’d you know?’

“It was the hat. You have to understand cowboys here. Their hats are like their fingerprints. The way they wear it, the headband, just old cowboy hats, get it?

“I told him my grandmother lived on Walnut Street. I used to visit her and watch him across the street.

“ ‘You used to sit on the front steps of your house and you would braid horsehair into key chains. You wore your hat just like you do now. You’d push your hat back and then you’d roll a cigarette with one hand.’

“Anyway, every time I went to see my grandmother I would visit him, and we would talk. I’d walk him around the block in his wheelchair and sometimes I would sneak him a cigarette. One day he started talking about his mother, and I could see he was getting emotional, like he was seeing her.

“ ‘Do you see your mother with us?’ I asked.

“ ‘Yes I can.’

“He started making this noise like click, click, click. I said, ‘What is that? What’s that noise?’

“He said, ‘It’s my mother.’

“ ‘What is she doing?’

“ ‘She’s making tortillas.’

“ ‘What’s the noise?’

“ ‘It’s her ring hitting the rolling pin.’

“And then I remembered hearing that as a kid with my grandmother. I had forgotten all about it.

“Then I asked him a question. ‘Was your mother a pretty lady?’

“He asked me to get closer and he hit me with his hat. ‘What was that about?’

“ ‘Don’t worry, get closer again.’

“ ‘No, you’re going to hit me.’

“ ‘I’m not going to hit you,’ he laughed. There was a twinkle in his eye. ‘Why would you ask such a stupid question?’

“ ‘What’s stupid about it?’

“ ‘Well, have you ever seen an ugly mother?’ ”

This is the kind of story that could plausibly be told anywhere: at a barbershop in an urban neighborhood, on an airplane, or in a book of folklore. It conveys special meaning in this context because of its smalltown location. It illustrates the local knowledge that comes from living in a community for a long time and includes knowing the fingerprint of an old cowboy hat. It underscores the slow passage of time and continuities of life.

The story points to another feature of small communities as well. Research on memory suggests that it is somehow bundled into mental packages that can be triggered into consciousness by the right stimuli. The stimuli that work best are sensual: smells, tastes, tactile impressions, sights, and sounds. This is why detectives take eyewitnesses back to the scene of a crime, hoping that a forgotten memory will surface. It is the reason abstract concepts are more difficult to remember than an experience of a place rich with sounds and smells.18

Mr. Segundo tells the story to show why places have special meaning. When he walks down Walnut Street where his grandmother used to live, he can hear the click, click, click of her ring on the rolling pin. He can see Don Pedro across the street pushing his hat back and rolling a cigarette. Visualizing Don Pedro in his mind’s eye, he is reminded of hot days as a boy working in the fields and the smell of fresh-cut hay. “I walk past a vacant lot. It’s not just any vacant lot. It’s where I played as a kid.”

If we are to understand the meaning of community, we must include the mental associations that connect experiences and places. This is why we decorate our homes with photos and memorabilia. To do otherwise is to live among mass-produced items that speak only of consumption. Community extends the principle of home to include its wider surroundings. The old school and park are meaningful because they have been there for a long time, and because one’s personal experience is intertwined with their meaning.

The experiences that familiar places bring to mind are not always pleasant. The park that Mr. Segundo is now able to visit was once restricted to the Anglos who lived on that side of town. Walking through it reinforces his views about the possibility of change as well as his memory of the past.

Reminiscing is an important part of small-town life. Telling stories of the past keeps the past alive. Having the places nearby that prompt the stories helps associate them with the community. A town seems like a community because of this mixture of places, memories, and people with whom these memories can be shared.

GROWING UP AUTHENTIC

Apart from the fact that intergenerational mingling and reminiscing is possible, residents often argue that small towns are the ideal place to raise children—a further connection with the idea of communities needing to be the right size to be nurturing. Child rearing is clearly a matter of practical significance for the many residents of small towns who are in fact raising children. Its larger symbolic significance is evident as well, especially in the frequency with which residents who no longer are parents—and perhaps have never been—mention it. Childhood connotes both innocence and vulnerability. For a place to be conducive to child rearing, it must afford an opportunity for innocence to be expressed and safeguard against threats to vulnerability.

At first blush, this emphasis on child rearing usually means that small towns are safe. Children can play in the yard without supervision and wander to a friend’s house without parents worrying.19 Residents point out that crime is low, traffic is sparse, and schools are within walking distance. And their perceptions are warranted, judging from uniform crime statistics, which show that crime rates are lower in smaller towns than in larger ones, and lower still among small towns in nonurban areas (figure 3.2).20 Of course this impression of safety is tempered by the fact that children in small towns can get in trouble just as easily as in cities and suburbs. And for that matter city parents would argue that opportunities for cultural enrichment, ballet, art lessons, ice skating, lacrosse leagues, gymnastics, and almost everything else are greater in larger places.

But small-town parents often refer to something deeper that they see in small places. This is the freedom they think children need to explore as they grow and develop: getting outside, roaming through backyards and over fences, collecting toads, leading a kind of Tom Sawyer and Huck Finn existence, rather than having structured activities, fixed schedules, and adult supervision. These are the ideals. Collectively, they constitute a definition of authenticity. Children who develop an authentic self, residents contend, have had the freedom to spend time playing, being outside close to nature, being by themselves, and learning without close monitoring who they are.21

One parent quotes the adage, “The work of childhood is play,” and stresses that play “has to be without adults.” That could happen in suburbs, and the saying probably described life in urban neighborhoods a generation or two ago, this parent feels. And yet the seeming lack of organized opportunities in small towns appears to be an advantage. It provides the space in which play can happen—literally, in fact, since the average person has considerably more square footage in a small town than in larger communities (figure 3.3).22 The further advantage of growing up with freedom to play and space in which to roam, small-town residents argue, is that children grow up to be better rounded and more genuine. They are imagined to be more in charge of their lives, better able to make their own decisions, more self-sufficient, and less influenced by the pressures of large institutions that necessarily weigh down on an individual.

Figure 3.2 Crime rate by size of town

It is interesting, certainly, that townspeople and the researchers who study them have varied and even conflicting views of exactly how—and whether—small towns promote authenticity in children. During much of the nineteenth century, it was commonplace to assert that fresh air, hard work, and room to roam resulted in healthier children being raised on farms and in small towns than in squalid urban contexts. But by the start of the twentieth century, that perception was changing. Cities were thought to be attracting the best and brightest, leaving behind uneducated, unmotivated, and perhaps intellectually inferior children in smaller places. In 1915, the renowned sociologist E. A. Ross declared that whole sections of rural America were left with “communities which remind one of fished-out ponds populated chiefly by bullheads and suckers.”23 Naturally, that comment does not sit well with researchers who observe better developments in small towns. “Those bullheads and suckers left behind in Midwestern rural communities spawn smart and capable youth, generation after generation,” rural sociologist Sonya Salamon concludes.24 The question is why.

Figure 3.3 Ambience by town size

On the one hand, freedom to explore and play without adult supervision is indeed one possibility. Some research suggests, for instance, that “downtime” is essential to childhood development and more effective learning among adults, whereas too much structure and time that is too thoroughly programmed can be detrimental to creative thinking.25 Authenticity may be nurtured in those moments when self-reflection happens without conscious thought. On the other hand, researchers like Salamon suggest that the informal monitoring that happens in small towns matters more. As residents themselves observe, children are mentored by not only their own parents but also neighbors who watch out for them, teachers who also live in the community and perhaps are neighbors, and opportunities to participate with adults in community activities, such as local improvement projects. Rubbing shoulders with multiple role models may be the source of a better-rounded personal identity.

If children somehow grow up to be more authentic in small towns, adults insist that relationships with other adults are also more authentic. It is the scale that matters, they say. “Well, it’s small enough that you know a good deal about the people who live in town,” a resident of a town of two thousand says. “It’s very neighborly.” Mr. Grimshaw, the investment banker, observes that the advantage of living in a smaller place is that one’s circles of activity are more likely to overlap. “If you’re working in the city,” he explains, “you’re probably going to get out to work and then get back to your community where you live, so you’re living in two worlds, whereas here you’re living in both your worlds at the same time. Your business contacts and your social contacts and your neighbors are all the same people.” He says that makes the relationships more personable and meaningful. Similarly, a woman who lives in a town of a thousand and regularly visits people in other small towns as part of her job comments, “They just seem to be more genuine, more helpful, more caring. I mean the whole community is a caring community. I travel in six counties, so I see the same thing in the other small towns. People are good and they are a caring kind of people who are easy to get along with most of the time. And the times that I’ve been in the city, you don’t get that feeling. And I don’t know why it’s that way, but the people are different.”

Part of what it means to be authentic, in these residents’ views, is being sufficiently well rounded to take care of oneself. Of course this definition of authenticity is arbitrary. Authenticity could just as well mean that a person knows when to depend on others. But in small towns, residents have the sense that in the past, people were somehow more authentic because they lived close to the land, raised their own food, cooked their own meals, and were less dependent on the marketplace. One woman provides this illustration. She says there wasn’t a good grocery store in her hometown, but that was good because most of the townspeople raised some of their own food. She had a garden and kept some chickens in the backyard. Most of her neighbors, she notes, cut their own firewood and had wood-burning fireplaces. It made her feel good that if something happened in the world, like the electricity going down, people in her town would probably be OK.

What people like about small towns becomes clearer when contrasted with the remarks city dwellers make about their communities. Consider how a lifelong resident of a city of two million describes her community. Although the suburb in which she lives has a population of only twenty-two thousand, she thinks of her community as the larger metropolitan area. She portrays it as a “friendly, open” city, but dwells at greater length on its “good amenities.” She says these include good sports teams, a sophisticated level of fine arts, and music. It is a good place to live, she explains, because it is “easy to fly in and out of,” and “lots of people here are well traveled.” She says that the traffic isn’t bad, but backtracks to acknowledge that there are lots of cars and suburban sprawl. When pressed to explain what she means by friendly, she says “family friendly” is what she has in mind. To her, that means that there are “many activities, many options for families to do.”

Or consider the comments of a forty-five-year-old banker who lives in a metropolitan area of half a million three hours from the town of two thousand where he was raised. Having lived in a small town, he is able to draw the comparison and even sees some similarities. He confesses that he sometimes wishes he were still in a small town, but it is unlikely that he will ever live anywhere besides a city. He has made a success of his career, and says that he and his family live comfortably. He likes his community. But his relationship to it is instrumental rather than one of deep emotional attachment. He explains that his reason for living there is that he was looking for a job after college and happened to find one in this place. What he likes best about his community is that it has been growing lately. Somehow, he is proud of that. Even though he dislikes the added traffic congestion and noise, it affirms his own sense of worth knowing that other people are coming to live in his community. His thinking does not venture far down that path. Instead his mind turns quickly to the instrumental benefits of living in an expanding community. Population growth is good for the tax base, he says. “There is a lot of stuff going on. There is more shopping.”

Discussions of what is authentic and what is not are always rich with irony. The special irony that attaches itself to the statements townspeople offer is that they are effectively turning one of the most familiar stereotypes about small towns on its head. In that view, attaining an authentic self—which means somehow finding the “real you”—is impossible in a small community because of its oppressive demands for conformity. Instead, residents argue, a small community is a place of freedom. Or more precisely, a secure space patrolled at the edges by attentive, caring adults (parents and neighbors) who give children sufficient freedom to explore, play, and be close enough to nature to discover who they really are. The city, in contrast, inhibits the search for a true self. A person there, bombarded by advertising and the cacophony of competing voices, more easily succumbs to self-deception.26

A SPACE FOR FAMILY

When small-town residents contend that their community is a good place for families, they usually have in mind raising children, but relationships with parents and responsibilities toward them frequently matter as well. These relationships are part of the reason people remain in small towns or return to live in these communities. It may be that the family farm or business has been in the family too long to be abandoned, or the decisive consideration may be a parent’s death or ill health. An adult child may give up plans for a life elsewhere in order to care for a parent’s needs.

The sacrifices that parents make for their children or their parents are probably no greater on average among residents of small towns than among inhabitants in cities and suburbs. The community nevertheless figures into the meaning of these sacrifices. The family obligation becomes part of the story of why a person has chosen to live in a small community. The story reinforces the connection between community and family. It dramatizes the importance of family, and in some instances encourages people to behave in ways that strengthen that value. Family ties then matter not simply as a belief but also as an activity that is considered significant enough to work at in order to maintain.

The thinking that goes into decisions about family and community are always complicated. A good way of teasing out some of this complexity is to consider the story of Arlan Harding, a postal worker in his early fifties. He lives in a town of fewer than four hundred people nearly a hundred miles from the closest city. The average age of residents in his community is considerably older than in the rest of the state. Not a single new house has been built in the last decade. Mr. Harding is one of the few who graduated from college. In fact, he has five years of college and majored in prelaw in hopes of going on to law school. He had just graduated, however, when his father was diagnosed with cancer. Mr. Harding put his plans on hold, and returned home to be with his dad and help his mother with the little newspaper his parents were putting out each week. His father died two years later. Mr. Harding stayed on and continued to assist his mother, who outlived her husband by nearly two decades. He never pursued his dream of becoming an attorney and living in a city.

A story like Mr. Harding’s can be interpreted in several ways. As an only child, he felt a special responsibility to be with his father and help his mother. They had no one else. It was uncertain how long his father would live. His mother was still in good health, but had no place else to go after her husband died. Still, Mr. Harding figures in retrospect that the decision to stay was entirely his. “I never felt pressured or tied down,” he says. He could have sold the newspaper and persuaded his mother to move or do something else. “I felt like I could have gotten out of it, sold it, done whatever at any time.” Instead, he settled down, got married, kept the newspaper going, and worked at the post office because the newspaper was hardly breaking even. “You get comfortable,” he adds. “You get complacent, and the longer you’re in it, the easier it gets.”

Whatever a person thinks about it later, the path not taken is always there in the shadows of one’s imagination. “At first I kind of resented being back here,” Mr. Harding acknowledges. “The idea was to get away. You go to college not to move back to a town of 350 to use your degree.” Yet as the years passed, he realized that he was using his college training, especially in editing the newspaper and advising his children about their own futures.

If the small town was not what he had hoped for, it at least had its own advantages. Despite their meager incomes, he and his wife purchased a big old house that they love, and have invested their time and energy into restoring it. The workdays are long, starting at six each morning with the newspaper, sorting and delivering mail from eight to four six days a week, and working again on the newspaper until ten or eleven each evening. “I don’t want to sound like Garrison Keillor,” he says. “If I could, I would rather live in a town of maybe ten thousand than here. But this is comfortable. You know people. It’s a slower pace, almost to the point of dozing.”

Dozing perhaps, although it is difficult to see that in Mr. Harding’s case. He and his wife hardly ever have time for a nap. The reason is mostly the long hours they both work. The slower pace is less evident in their daily schedule than in their sense of not being overly stressed. “Going postal” might be an appropriate phrase for a harried postal worker in a large city, but not in a small town. Mr. Harding believes that the life he has made for himself has provided the time and space in which to behave as a responsible son as well as father.

Saying that a small town is a good place to raise children is too clichéd to sound quite right to Mr. Harding. “We’re not Father Knows Best or a Norman Rockwell painting,” he says. The “we” refers to the hundred or so families who populate his town. It is all too common for people in his community to pop a slice of frozen pizza into the microwave and call it dinner, he thinks. It takes more time, but he and his wife maintain that the extra time is worth it to have family meals that take longer. “I guess we’re old-fashioned. Believe it or not, we actually have sit-down meals with meat and vegetables. And we have a garden. Our kids actually know what vegetables are.”

Undoubtedly Mr. Harding’s neighbors would each have a slightly different story to tell. He does not consider his typical, and it probably is not. What his story illustrates is one of the many ways in which thoughts about family responsibilities and living in a small town come together. Having sacrificed a more prestigious career as an attorney to deliver mail and run a small-town newspaper, his feeling of having done the right thing in helping his mother is strong. It is sufficiently strong to reinforce the value he attaches to having sit-down dinners with his children. It worries him that more children are not learning about vegetables. He fears that families are just “kind of disintegrating.”

DRAWBACKS OF LIVING IN A SMALL TOWN

Although people in small towns generally say they like living where they do, they are not Panglossian enough to say that everything is to their liking. Many of their complaints have nothing to do with the size of the town itself. People in the Midwest, for example, talk about the harsh winters, and people in the South and Southwest say they hate the hot summers. Their complaints about the town itself are seldom specific to the town, but reflect problems common to many small towns. As much as residents may talk about liking the open spaces or being near farms, the truth is that most towns are located in spots that would hardly have been selected for their beauty or the comforts they provide.

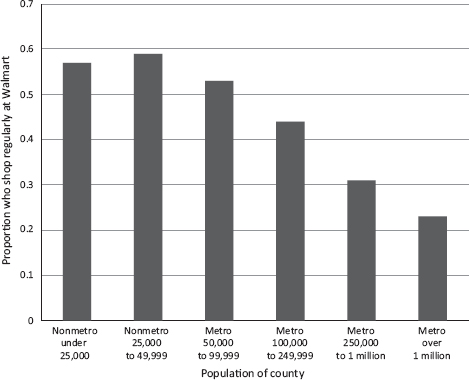

A few years ago, the Economic Research Service of the US Department of Agriculture developed a natural amenities scale that scored places in terms of the environmental qualities most people find attractive, such as mild winters, winter sun, temperate summers, low summer humidity, topographic variation, and water area. Most nonurban small towns—and the majority of the population living in them—were in locations that scored below average on the amenities scale (see figure 3.4). There was also a notable contrast between the scores of nonurban small towns and those of larger cities. For instance, only 8 percent of nonurban small towns received scores higher than “1,” whereas 42 percent of cities with populations of fifty thousand or more did.27

Other than bad weather or a lack of natural amenities, one of the more commonly mentioned drawbacks of living in a small town is the lack of cultural activities. As one community leader chuckles, “If you like high school athletics, this is a great place to be, but in terms of concerts, artists coming here, lecture series, we just don’t have that.” At first I was surprised that this came up as often as it did. My assumption—naive in retrospect—had been that people in small towns probably do not care much about such highbrow activities as orchestra concerts, the opera, and viewing fine art in museums; if they did, they would have lived elsewhere. I realized, though, that townspeople frequently visit concert halls and galleries in cities, and they may have relatives who live near such amenities, or they at least have an appreciation of the arts because of television or high school programs. When this was the case, they do miss the fact that cultural activities are not available in their own communities.

Figure 3.4 Amenity scores of small nonurban towns

Besides cultural events that people in cities and suburbs can more easily attend, the broader cultural atmosphere of small towns is disappointing to residents who long for the kind of interaction they experienced in college or imagine exists in other places. “We are college educated,” a sixty-year-old businessperson in a town of five hundred says, mentioning his own background and that of his wife. “We miss the interaction with other college-educated folks and the professional people we lack out here.” He says the Internet and email have made it easier to feel connected to a community of better-educated people, but he regrets not having the opportunity to visit face-to-face.

If the lack of cultural activities is a drawback, it is nevertheless one that many townspeople manage to overcome. Middle-class people in small towns take advantage of cultural opportunities when they are on vacation or visiting relatives in cities. Some take in concerts and museum exhibits by driving an hour or two. They figure it is no harder to enjoy the arts than if they lived in a metropolitan suburb and had to drive or take public transit into the heart of the city.

We also came across a number of people who participate in cultural activities within their own towns. These are usually residents of towns of at least three to five thousand people, and more often live in towns of ten to twenty thousand. One example is a college town of three thousand that has a major art gallery along with an annual concert that attracts audiences from throughout the region and is home to a nationally renowned photographer who has a gallery on Main Street. Another is a community of approximately thirteen thousand that has its own orchestra. Yet another is a town of fewer than two thousand known regionally for its productions of popular Broadway musicals, such as Oklahoma and My Fair Lady.

The mental adjustment townspeople make when cultural activities are truly lacking involves emphasizing the simpler pleasures of small-town life, such as the joy of working hard and being useful to the community. For these residents, the beaux arts are desirable on rare occasions, but unnecessary most of the time. “If you’re a person who has to be entertained,” a resident of a town of two thousand explains, “there’s not a lot of entertainment here. For most of us who live here, we know how to entertain ourselves.” Thus, if asked specifically to mention something their town lacks, they point to the absence of a major museum or concert hall, but from day to day these are hardly sources of serious discontent. Indeed, survey responses show that on average, residents of small towns are just as satisfied with the cultural events available in their communities as are residents of cities and suburbs.28

What cannot so easily be compensated for are the advantages for children of living in a place with a larger school that offers a wider range of educational opportunities, including orchestras, dramatic productions, dance ensembles, and visits to museums. Although consolidated school districts have broadened these possibilities in many small towns, residents still point to disadvantages. The quality of smaller districts in rural areas is sometimes relatively good because of the property taxes supporting the schools, and yet there are limitations on the variety of science courses that can be taught, for example, or availability of music and arts programs. We talked to some parents who had driven their children to larger towns and worked out arrangements for their children to take advanced placement courses at high schools in those towns. We also spoke with people who had been frustrated because the small-town high school placed so much emphasis on sports compared with academic achievement.

Naturally, many of the townspeople we talked to recognized that unemployment, low wages, a lack of jobs, and inadequate social services were a serious deficit in their community. Although the extent of these concerns varied, and were often mitigated by inexpensive housing and government transfer payments, we found numerous instances in which residents were troubled by local economic conditions. This was especially true when the only manufacturing plant in the community had closed or mines in the area had been shut down, but was not limited to these circumstances. In one of the towns we visited, residents were able to find steady employment at an automobile assembly plant thirty miles away, but rising fuel prices and a dearth of day care facilities were making it difficult for residents to commute. In another town, community leaders were keeping ahead of the grass that grew through the cracks on sidewalks along Main Street, but were unable to pay for a water treatment plant that the community desperately needed. In yet another town, unemployment was low and median household incomes were close to the state average, and yet the community’s remote location made it difficult for residents to find fresh produce. In fact, a committee that monitored the situation discovered that even canned goods at the local grocery store were sometimes a year or two beyond their posted expiration dates.

The other drawback townspeople frequently mention is the ease with which gossip spreads. “I call it the small-town disease,” a resident of a town of sixteen hundred observes. He says farmers in his community are always watching what the other guys are doing. For example, he was thinking about buying a piece of land and knew from long experience word would spread at the coffee shop before the deal was ever consummated. Knowing that, he asked a friend to be a mole at the coffee shop and report whatever was said. “There’s just too many people watching what you’re doing,” he sighed. This is the downside of people knowing and caring about one another. “I was at the local restaurant,” one woman recalled, “and I overheard people in the next booth talking about what a scandal it was that my parents were getting a divorce.” A man in a town of eight hundred related a similar incident. He seldom got his hair cut in town, but did one day and within a few hours heard from two neighbors what exactly he had said to the barber.

If gossip is the small-town disease, it is nevertheless one that warrants caution in interpretation. An earlier generation of social scientists, writing at a time when all things progressive were considered to be happening in cities, sometimes described small-town gossip more as a plague than as a simple disease. In a study of a town in Colorado published in 1932, for instance, Chicago-trained sociologist Albert Blumenthal found gossip to be a pervasive feature of community life—so petty as well as so often false and scandal ridden that it shaped public opinion, and frequently constituted a serious invasion of privacy. Another sociologist, drawing on Blumenthal’s study concluded that small-town gossip “makes every person’s tongue a whip to discipline his neighbor and, at the same time, puts every neighbor at his mercy.” Yet it was the residents themselves who informed Blumenthal that gossip was petty and false, and who often singled out the town’s gossips for ridicule. That was evident in our interviews as well.29

Because they recognize it as a problem, residents do find ways to push back against gossip. One way is to keep silent about business dealings and other private matters, such as how much money a person makes or whether the corn crop was as good as expected—easier now than in Blumenthal’s time because of changes in business practices and information technology. Another way is simply to shop out of town. Townspeople also respond by criticizing someone who develops a reputation as too much of a gossip. As one woman explained, a gossip who claims to know about everybody’s business is “a major turnoff” and soon would not have many friends. Implicit norms exist as well about what can and cannot be gossiped about. For example, it is more acceptable to gossip about someone being in the hospital than about seeing something illicit through a neighbor’s window. Despite its problematic aspects, gossip also serves valuably to spread useful information and maintain social ties. Residents we talked to mentioned, for instance, helping neighbors whose needs became known through the grapevine, and newcomers gained information about where to shop and who to call on for home repairs.30

One might expect the drawbacks seen by city dwellers to be the exact opposite of those described by small-town residents, and to some extent that is the case. Urban residents bemoan traffic, congestion, and noise. They list rapid population growth and not knowing anyone among the main disadvantages of living where they do. Yet it is important to note that the standard of comparison for city residents is often not the small town but rather other cities. Indeed, city residents frequently seem defensive about how their communities compare with cities that are larger or more prominent. Comments such as “Of course, we’re not New York or Los Angeles, but we’re more sophisticated than people might think” are not unusual. Or, “People come here and it’s better than they expected. We’re not provincial. We’re knowledgeable about the world.” Or, “We are more genuine here, not like some of that pseudocosmopolitanism you find in other cities.” Unless they had actually lived in a small town, they had in mind that the crucial comparisons were other cities, and not unrealistically so because their friends and coworkers, and often they themselves, had lived in other cities. The comparisons dealt with size, weather, jobs, sports teams, and airports.

The comments of people who live in suburbs offer a more nuanced comparison with those of small-town residents. In many ways, suburbanites identify so many of the same attributes as townspeople that it almost seems that suburbanites are trying to replicate small-town life in these larger, more metropolitan communities. For example, they insist that their communities are safe, friendly places in which to raise children. By safe, they do not mean safer than in small towns but rather in comparison with inner cities, where they assume crime is higher. By friendly, they do not suggest, as small-town residents often do, that they are acquainted with nearly everyone but instead that they have found a few like-minded people with whom they could be friends. If they had children, suburban residents say less about children being free to roam the neighborhood, and more about excellent schools, fine after-school programs, ample parks and recreation facilities, and other young families.

Somewhat more surprisingly, many of the people we spoke to in suburbs described their communities as self-sufficient, meaning that everything a person could possibly want was readily available. It was unnecessary, they said, to venture beyond the confines of their own community. A woman in her forties who had lived in cities as well as the suburb in which she and her husband were currently living, for example, said her neighbors frequently remarked that “they have everything they need right here. There isn’t a need to go anywhere.” That was similar to the way residents of small towns talked. It was not literally true in either case, by people’s own admission. They did drive to airports, go shopping some distance away, and fly to visit loved ones. But what they liked to feel was that their community had all the basic essentials nearby.

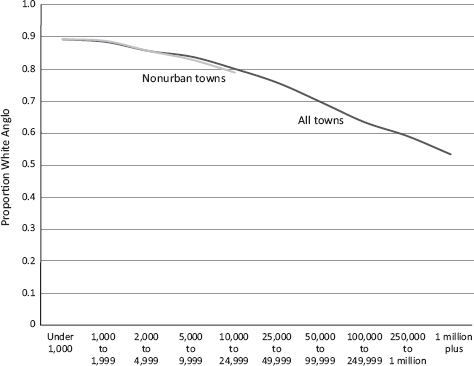

The clearest contrast between suburbanites and townspeople is in how they understand their community’s authenticity. Whereas townspeople insist that their community exemplifies authenticity, suburbanites more often say something is inauthentic about theirs. “It’s not reality,” one suburban resident explains. “It’s not even a dose of reality.” Says another, “Look at things around here very long and you realize everything is artificial. Even the buildings aren’t quite what they seem.” Among those who make comments like this, several reasons become evident. One is that the suburb’s residents seem too ethnically and racially homogeneous. “People are the same here and they like their sameness,” one resident comments. People in small towns are homogeneous, too, and they recognize that sameness. But suburbanites live next door to inner cities and perhaps even other suburbs that make them aware of greater diversity, so they are more likely to say that homogeneity is not reality. A second reason suburban life is regarded as inauthentic is that the suburbs are usually newer and change more rapidly than small towns did. People point to recently constructed malls and housing developments, and contrast those with older downtown areas in cities or farming communities. That contrast is evident, too, in comments about people. In small towns people are viewed as natural lifelong friends, whereas in suburbs friends are chosen and thus are understood to be somewhat arbitrary.

The other reason suburbs are viewed as artificial is that residents there look at neighbors who live in mansions and drive fancy cars, and wonder about those neighbors’ values. One hears remarks such as “I see people driving eighty thousand dollar SUVs,” “I was in somebody’s house, and they had twenty-two bar stools around their bar,” or “There’s a family with a full movie theater in their house. How much do you need? I mean, come on!” In contrast, residents of small towns usually know their neighbors well enough to vet their neighbors’ values or have stories of caring that vouch for the community’s wholesomeness. They also claim that neighbors mostly do not engage in conspicuous consumption. That makes the small town seem authentic whereas suburban life seems unnatural.

An important caveat to the contrasts between small towns and suburbs is that life as it is actually experienced in small towns is sometimes more diverse than in suburbs or even cities. We heard this especially in towns that had at least five to ten thousand residents. What people mean when they say their town is diverse is that they personally know and interact with people who are different from them. “You are more likely to know and be friends with a wider variety of individuals than you might in a larger city,” a resident of a town of about ten thousand asserts, “because you are going to recognize and acknowledge people in the store and the bank and church. You are going to have more contact and have a better chance to develop a relationship with them.” Whether that could be proven true is difficult to say, but it does make sense. In this man’s town, which probably is not atypical, zoning laws have been established only in the last few years. During most of the town’s history, it was possible for a mansion to stand side by side with a shack—literally. Rich and poor were neighbors. That did not mean they spent much time together. They did, however, know one another by name and could greet each other on a first-name basis at the grocery store. Friendship was somewhat less selective, people said. They were thrown together by virtue of living in the same small community, whereas in a suburb or city they would have chosen friends because of similar interests and lifestyles. Other people that someone may have seen at the bank or grocery store would have remained strangers.

HOW SMALL TOWNS ARE CHANGING

The question of change in small towns, as I have suggested, is easy to misread. This is partly because of the sense one acquires both from talking to residents and hearing outsiders’ remarking that nothing ever changes in small towns. It also stems from the more general perception so often promulgated in the media and fiction that small towns are a thing of the past, and thus must surely be declining. This view corresponds closely with that gnawing fear—the one that never seems to quite go away—that community itself is on the verge of collapse.31

The truth is that many of America’s smallest towns have in fact been losing population—at least a little. In addition, many towns have been affected by economic difficulties, and have lost jobs and population for that reason. This is especially true of towns that are heavily dependent on agriculture and mining.32 Perceptions and reality do not always match, but both are important. It makes no sense to dismiss the perceptions held by residents of small towns as a kind of false consciousness. My interest here is only partly in the fact that population may be declining or growing. I am more intrigued by how townspeople themselves perceive the changes taking place in their communities.

Residents in towns of fewer than two thousand people frequently mention that the first thing someone who had lived there twenty-five or thirty years ago would observe now on returning would be a smaller population, a quieter Main Street, and less business activity. “They would notice that there weren’t as many people,” a man in a town of nine hundred says. He is right. In 1980, the population of his town was fourteen hundred—half again its present size. “They would notice that there weren’t as many shops,” he adds. “Thirty years ago on Saturday night, you could drive down Main Street and see cars. Now you won’t see cars.” In a similar vein, another longtime resident of a small town says that even when most of the people in his community lived on farms, they all knew each other because Saturday was the big shopping day. Her family came to shop, she remembers, and often stayed into the evening just talking with people. That no longer happens in her town.

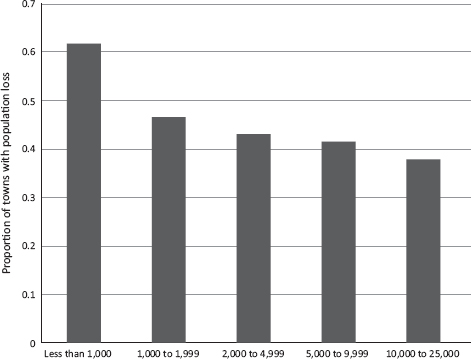

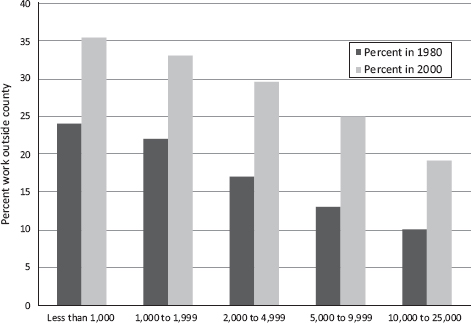

Nationwide, 62 percent of all nonurban towns with fewer than a thousand residents in 1980 became smaller during the subsequent three decades, and even among towns with populations between five thousand and ten thousand in 1980, 42 percent declined in population between 1980 and 2010 (figure 3.5).33 Many of these towns had been losing population for a long time—some for most of the twentieth century. They had been founded in team-and-wagon days when farmers considered it a major outing to travel three to five miles to the grocery store and lumberyard. Many of the towns were established by railroads that needed stops every seven to ten miles for coal and water to power the steam locomotives. As farms became larger, fewer farmers lived in the vicinity of these towns. Better vehicles and improved roads made it possible to travel ten to twelve miles to a larger town instead of five to the nearest village. Much of that population decline in rural communities occurred in the 1940s and 1950s when marginalized farmers left to take jobs in other sectors of the economy. Further decline occurred in the late 1970s and 1980s when government policies restricted grain exports, and low prices for grain and livestock forced additional reductions in the number of farmers.34

Figure 3.5 Towns losing population

In the past quarter century, further changes in agriculture have contributed to the decline of small rural towns. As agriculture has become more specialized, the self-sustaining diversified family farm has declined, and is now replaced by contract farming that involves networks among large feedlots, trucking companies, and meat-processing plants. A farmer we talked to describes the changes this way. “Twenty years ago if you drove by a farmstead nice and slow, you would see cattle, hogs, sheep, and chickens. You might see guineas, dogs, and cats. You don’t see that anymore. You see sheds and equipment. Diversification is no longer there. The farmer still may hold an interest in cattle, but they are in a feedlot in another part of the state. He buys cattle he’s never seen and has them trucked to a feedlot.” The man says this is true in his own case. He has three hundred cattle he has never seen in a feedlot two hundred miles away. They are being fed a scientific diet that gives them just the right number of daily calories and keeps their electrolytes in balance. This arrangement means increased population in the community with the feedlots because of a growing demand for low-wage workers, but it contributes to population loss in the cattle owner’s community.

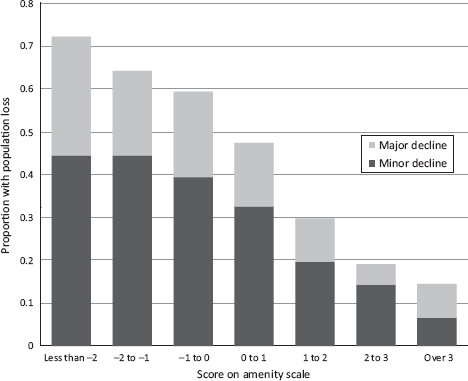

Figure 3.6 Decline by amenity ranking

The towns that are particularly at risk of losing population not only are small but also are located in places with natural amenities that hold few attractions (see figure 3.6). Upward of 70 percent of towns with the lowest scores on the US Department of Agriculture’s natural amenities scale have lost population, compared with fewer than 20 percent of those with the highest scores. The difference reflects the fact that the latter can attract tourists and retirees, whereas the former cannot. The fact that the majority of small towns have low amenities scores is part of the reason that so many have lost population.35

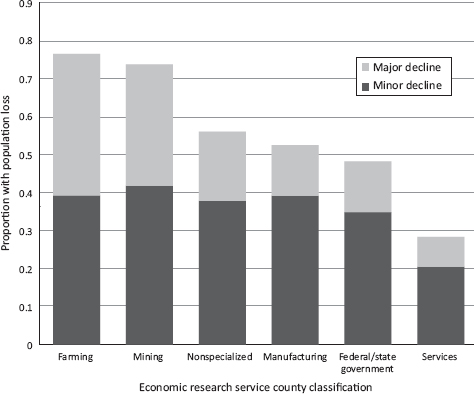

Population trends illustrate another critical shift in small towns. Traditionally, small towns existed largely to support farming communities. Then, during the latter half of the nineteenth century, towns increasingly supported the mining and manufacturing populations that played an important auxiliary role in urban industrialization. But in recent decades, mechanization in agriculture, mine closures, and the relocation of manufacturing to other countries all have meant that small nonurban towns are no longer as significantly sustained by these sectors of the economy. The most serious population losses have been in small nonurban towns located in counties that are farming dependent, mining dependent, economically nonspecialized, or manufacturing dependent, while the least significant declines have been among towns located in counties that are dependent on federal or state government employment or in services (as shown in figure 3.7).36