Habits of Faith

The Social Role of Small-Town Congregations

VALLEY VIEW UNITED METHODIST CHURCH occupies a spacious corner lot conveniently located just a block from the town square which surrounds a modest two-story county courthouse constructed of native limestone. The church’s stately red-brick building with a tall bell tower rising above the front door was erected a century ago to replace the small frame church constructed in 1870, two years after the congregation was organized by a circuit rider. The sanctuary with curved wooden pews easily holds two hundred worshippers, but on most Sundays attendance at the eleven o’clock service is fewer than half that number. This morning, the preaching service and Holy Communion are being conducted by candlelight. Heavy rain on Saturday afternoon flooded the river that runs through the south end of town and knocked out the area’s electricity.

It is not uncommon in small towns to find several aging churches within a block or two of Main Street or the town square. One was probably founded by the Disciples of Christ, another by Presbyterians or Congregationalists, and another by one of several Baptist denominations. There may be a Lutheran church and probably a Roman Catholic one. In addition, at least one newer church building of modern design is likely to exist on the edge of town, several modest storefront or residential congregations are tucked along side streets, and perhaps a metal-frame edifice or two with a church sign in front are located on the outskirts of the community. Filmmakers and writers still depict small towns with church spires rising above the trees along with hymns emanating from white-clapboard edifices. Those images may be dated and stereotyped, but religious congregations are still a vital feature of small-town America. Ask almost any small-town resident, whether they are personally religious or not, and the answer is nearly always that religion is an important part of their community.

When they talk about religion, moreover, townspeople hardly ever mean anything other than Protestant, Catholic, or other denominations in the Christian tradition. Although there may be an occasional Jewish, Muslim, Buddhist, or Hindu family living in the community, it is more likely that those families will travel to a larger metropolitan area to worship than to have a worship center associated with their own faith in the community itself. A study conducted in 2009, for example, identified 3,376 Jewish congregations nationwide, but only 15 were located in counties with populations of fewer than twenty-five thousand people. The same study identified 513 mosques nationwide, but only 3 were in counties this small. Of the 625 Buddhist temples identified in the study, 6 were located in small counties of this size, as were only 2 of the 183 Hindu temples in the study.1

The Valley View ministerial alliance recently canvased the community to see what could be done to increase church attendance. At the Congregational and Christian churches, both founded in the nineteenth century, attendance on Sunday mornings has fallen below a hundred. The Southern Baptist Church up the street from the Methodist Church is barely holding its own. Attendance at the new Lutheran Church on the edge of town and the Catholic Church is stable. Eleven other churches, mostly fundamentalist, Pentecostal, and nondenominational Bible congregations, are faring better, although none has more than a hundred members. Religion is nevertheless quite important in the community. The flagging attendance is partly because members more often spend their weekends visiting children living in cities and suburbs than was true a generation ago. The more serious source of decline is that the town is economically depressed and losing population. More than half the stores on the town square are vacant. After rising to four thousand in 1920, the population settled back to thirty-two hundred through the 1950s and since then has declined by a third.

Studies of churchgoing demonstrate that people’s habits are significantly influenced by their surroundings. When people move to a different region of the country, their religious participation increases if that part of the country has high rates of religious involvement. It decreases if the rate of involvement there is low.2 Research shows that religious participation among new immigrants to the United States is similarly affected. It rises in communities where churchgoing among the native-born population is high. It declines where native-born religious participation is low.3

The puzzle is how do people know? How do they know whether religious participation in their community is high or low? Especially if religion is as private as many observers say it is, how would someone determine that religion is or is not important? Is it because of particular individuals they meet? Is it because of reading statistics from surveys, canvasing the community, or some other information? Is it that people actually talk about their religious activities more often than might be supposed even in secular settings, as a study of volunteers at a soup kitchen found? Is it that people draw conclusions from viewing cars in church parking lots, as one team of observers tried to do?4

In a city, the information that shapes public perceptions of religious activity is probably a function of geographic region. Atlanta may be regarded as a religious place because it is in the South, whereas Boston may have the opposite reputation because it is in the Northeast. Small towns have a reputation of being more religious than big cities, perhaps correctly judging from surveys. But it is interesting to ask residents of small towns why they think religion is important in their communities. Doing so provides a window into the social role that small-town congregations play.

Townspeople usually do not try to judge the significance of religion by estimating how many people believe in God or attend church regularly. One of the few exceptions in our research is a man who figures that 95 percent of the townspeople in his community believe in God and at least 50 percent are at church on any given Sunday. This man happens to teach social studies at the high school. Another exception is a member of a Nazarene church in a town of about nineteen hundred. She is sure that nearly everyone in her community is affiliated with a church. The reason she knows this is that her congregation recently completed a survey of the town. I mention these because they are indeed exceptions. They illustrate that it is rare for townspeople to think about the importance of religion the way that social scientists do.

The common way of indicating the importance of religion in small towns is by pointing to the number of churches. “There are a lot of churches in town,” a man in a community of thirty-three hundred says. He isn’t sure just how many, but notes that three of them are different kinds of Lutherans. A lifelong resident in another town offers a more precise figure. “There are twenty-two churches in this county of about six thousand people. So I would say it’s more important here than in the bigger cities.” He conjectures the reason for the difference is that in cities, nobody knows whether you go to church or not, whereas in a small town “you have more accounting to the audience.” Churches are a visible part of his community because of their buildings. “Let me see,” a woman in another town says, “one, two, three, four, five, six.” She pictures the churches as she counts. “It’s pretty important,” she concludes. The membership at some of the churches is usually small, yet townspeople seem to take pride not in the size of any particular building but simply in the fact that there are a lot of them.

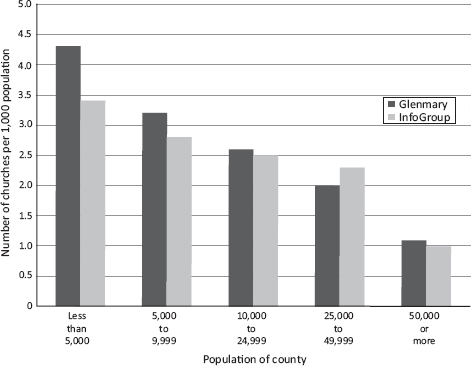

Churches are indeed more visible in small towns than in larger communities not merely because it is easier in smaller places for residents to visualize its main buildings but also because there are more churches per capita in less populated areas than there are in more heavily populated places. The data shown in figure 7.1 are drawn from two national studies, the first conducted in 2000 under the auspices of the Glenmary Research Center, and the second in 2009 by a commercial firm called InfoGroup. The studies provide somewhat-different results because of the methods used, but both demonstrate that churches are more abundant, relative to population, in smaller areas than in larger ones. In counties with fewer than five thousand residents, for example, there are approximately four churches for every thousand residents, but that number declines to about one church for every thousand people in counties of fifty thousand or more.5

Figure 7.1 Churches per thousand residents

In addition to the fact that church buildings are a more visible part of the community in sparsely population places than in urban areas, it is also more common for the average resident to be affiliated with a congregation. As shown in figure 7.2, the rates of adherence at churches range from more than 60 percent of the population in the least populated counties to fewer than 50 percent in the most populated ones. Similarly, actual membership in congregations is around 50 percent in counties with fewer than five thousand residents, but declines to 34 percent in counties with more than fifty thousand residents.6

The other tangible marker of religion’s importance is the fact that in many small towns, one evening a week is still customarily thought of as church night. This is the evening when cars are parked in front of churches and community leaders know not to schedule other events. “Oh, Wednesday nights,” one woman explains when asked to say how she knew religion was crucial in her town. “That’s our church night. Everybody knows, every organization, the school, everybody knows to never try to plan anything for Wednesday night. That’s church night.”7

Figure 7.2 Religious adherence and membership

People who estimate the importance of religion in their communities in other ways are usually residents who have lived elsewhere. If they have lived in cities, they say religion in their small town is more significant in comparison. This judgment is mostly from knowing friends and neighbors who do or do not participate in religious services. Occasionally the perception is based on some personal incident that is considered especially revealing. An interesting example is given by a woman who is Catholic but married to a Lutheran. After attending the Lutheran Church for several years, she decided to attend the Catholic Church some of the time. People were shocked, and several actually questioned her about it. “If you are Catholic here, you just don’t go somewhere else. And if you are Lutheran, you stay within the church. So the Lutherans kind of shunned me for a while because I was going to the Catholic Church, and the Catholic Church didn’t accept me because I hadn’t been going there all along.” This was her evidence that religion is key in her community.

Nearly every study of small communities conducted between the 1920s and 1950s suggested that religion played a crucial role in those decades. If residents of small towns still argue that religion is important, does that mean little has changed? Is religion a way of preserving the past in small towns, perhaps even more so than it is in cities and suburbs? Or is religion adapting to the changes taking place in small towns? The best answer to these questions comes from townspeople themselves. They talk glowingly of their congregations giving them a sense of continuity with the past, but also show that congregations are adapting to new challenges.

HABITS OF BELONGING

“Somebody asked me if I was a born-again Christian. I said I went to church every Sunday from the time I was out of the womb. I had to be darn sick if I ever got to stay home.” This is Emma Wilkins. She is a spry eighty-two-year-old who grew up in a town of eight hundred, married her high school sweetheart, and has been living in her hometown ever since. “You just do those things,” she says, describing churchgoing in the same way she talks about cleaning house and canning her own tomatoes. “They are just a way of life, I guess.”

Habits are much of what small-town congregations are about. Weekly services are routine, starting at the same hour, meeting in the same space that has been used for decades, singing familiar hymns, and seeing familiar faces. The worship service may not be as lively or exciting as those at a big church in the suburbs, but longtime members appreciate the familiarity of it all. The weekly services give a sense of regularity to the passage of time. Mr. Steuben, the auctioneer, and his wife attend a Mennonite church that has about six hundred active members—making it one of the larger congregations likely to be found in a small rural community and yet one that continues to exhibit decades-old customs. “One Sunday is not any different from another Sunday,” he says. “Oh, somebody will raise hell about something every once in a while, but that’s just a hiccup. Basically it’s a steady deal. It’s always there. You’ve got active members who keep the deal alive.”

Izzy Jorgensen, a member of a Lutheran church where about fifty people attend regularly, makes a similar observation. She notes that “every Sunday morning, somebody brings snack items and there’s coffee time, fellowship time before church ever starts.” That happens at nine o’clock, and then the service is from 9:30 to 10:30 a.m., and after that people break into groups of eight or ten to discuss the sermon. Committees meet promptly at 7:30 every Wednesday evening in the fellowship hall, and once a month the men get together for breakfast at the café while the women meet as a group just to talk and have a short Bible study. The steady deal, as Mr. Steuben would put it, is just as predictable at her church as at his.

When habits are this ingrained, just being there each Sunday is a mark of loyalty, especially if the sermons are dry and the music is bad. This is one of the reasons that people show up, even though they may be less than thrilled about what then happens. A lifetime Lutheran in a predominantly Finnish congregation, for instance, says his church has been putting on a dinner of sauerkraut and bratwurst for the Germans in his community for as long as he can remember. “I can’t stand either one,” he complains, referring to the sauerkraut and bratwurst, yet it is difficult not to participate. It says something good about people that they will stick with a congregation over a long period. A member of a Catholic parish in a town of ten thousand puts it well when he notes that what he likes best about the parish is its “continuity.” Many of the parishioners, he says, have been lifelong members. They have “stood by the parish through thick and thin.” That gives him a sense of history along with a feeling that people really care for the parish and one another.

As much as the continuity, it is the visibility of public behavior that facilitates regular participation in small-town religious activities. When people know one another in town as well as in church, churchgoing becomes part of their public reputation and this fact puts social pressure on them to be present at church services. People know that the car dealer goes to the Methodist Church and the bank manager is an elder at the Presbyterian Church. Parents’ public reputation affects their children’s behavior as well. People talk if the bank manager’s children are out drinking on Sunday night instead of participating in the youth group. Again, Mr. Steuben provides an example. His children were brought up in the same church that he was. When they were teenagers, they went through a phase when they did not want to attend Sunday school or go to the youth fellowship. Mr. Steuben told them in no uncertain terms, “That’s non-negotiable.” In fact, his opinion of other parents who did not hold their children to the same standard went down. It made him “real hacked off about the doggone deal” when parents weren’t pushing their kids’ “butts out the door” to get to church. The habit of going to church is simply ingrained, not only because parents believe this is the right way to live, but also because the community expects it.

The fact that churchgoing in small towns involves habit and depends on social pressure does not mean, of course, that everyone faithfully attends week in and week out. National surveys show that 36 percent of inhabitants in nonmetropolitan communities of fewer than twenty thousand residents claim to attend religious services weekly or nearly every week. That figure is only 5 percent higher than the national average for the whole US adult population. A quarter of small-town residents say they attend services less than once a year or never—a figure that differs little from the national average.

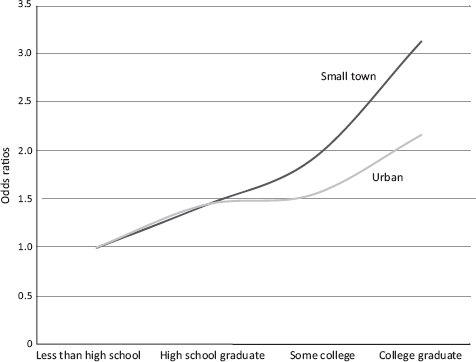

Figure 7.3 Church attendance by education level

But what is notable about small towns is the extent to which church involvement is expected among the community’s leaders and other upscale residents. As shown in figure 7.3, the odds of someone attending religious services regularly are higher if that person has more education, but those odds increase more dramatically among people living in small towns than among those living in cities or suburbs.8 This pattern is consistent with the fact (as I noted in chapter 2) that residents who live in “above average” homes, as judged by interviewers, are more likely to be involved in community organizations if they live in small towns than if they live in larger places. This difference pertains to religious organizations as well. In small towns, 54 percent of upscale residents belonged to a specific religious group of some kind, such as a fellowship group or Bible study, compared with 39 percent of upscale residents in larger communities.9

It is also evident from our qualitative interviews that church attendance and nonattendance are matters of public discussion in small towns. Residents talk about the religious affiliations of their friends and neighbors, and whether some neighbors do not attend at all. Clergy periodically canvas their communities to invite residents to church and discuss the results with their congregations. Clergy also serve on the boards of community organizations, and see members during the week at the post office or grocery store. They mention members apologizing for having missed the latest worship service or potluck dinner. Residents themselves volunteer in interviews that poor health prevents them from attending services often, they have to work on Sundays, or in a few cases, they have quit going because of a falling out with the pastor.

For those who do attend regularly, churchgoing is often reinforced by the fact that small congregations feel like families. “We’ve got a tremendous church family here,” a town leader in a community of two thousand explains. “We’re not terribly large. I suppose we have sixty or seventy people who come regularly. That’s our family. It’s terribly important.” His view is shared by a woman who attends a Congregational church of about a hundred members in a town of a thousand. “If you come to choir practice, it’s a family, and we’ve bonded. It’s an uplifting time, and you go home and say, ‘Boy, I’m glad I went to choir practice. I feel so much better.’ ” A Lutheran member in a town of thirty-six hundred chuckles, “It is a lot of family. The people who aren’t blood related to me, well, my church family is like they are.”

Although church leaders in large congregations in cities and suburbs also like to say that their churches are like a big family, the secret to this claim actually being a reality in small towns is the limited scope of a small community. Socializing occurs within the community. People share more than just the fact that they see each other for a few minutes on Sundays or sit together on a committee once in a while. They can talk about how the weather is affecting the local agriculture or how the proposed bypass will hurt the businesses on Main Street. People mention that their next-door neighbors also go to the same church, they go with fellow church members to a movie, meet someone from their church at the coffee shop, or spend time together on Sunday evenings at the Dairy Queen.

As an example, one man says that he and his wife have taken dance lessons with three other couples from their church. Another man mentions by name the two other couples that he and his wife know from church, but also play cards with and see during the week at school functions. There are still affinity groups, like there are in large urban churches. Mr. Parsons, for instance, says he and his wife belong to a couples’ group at their church of a hundred members. “In fact, last night we went out to one of our members’ farm pond and had a potluck out by their farm pond. Pot-lucks are great. I mean that’s the only way to eat, in my opinion, because you get a great variety and everything’s good.” But in small churches, affinity groups are less likely to separate people than is often true in large churches. The congregation remains intact as a single community. In the Parsons’s case, the whole church comes together routinely to organize a soup-and-sandwich dinner, host a pancake breakfast for the town, and have a cleanup day at the church.10

Data from a national study highlight the differences between small and large communities in churchgoers’ friendship patterns. Among active churchgoers nationally, those who attend larger congregations are more likely to report having more than ten close friends in their congregation—presumably because there are more people with whom to make friends. In small nonmetropolitan communities, though, nearly half of active churchgoers participate in congregations of fewer than two hundred members. That contrasts with only 18 percent of active churchgoers in metropolitan areas. Yet despite belonging to smaller congregations, 43 percent of churchgoers in small nonmetropolitan communities report having more than ten close friends in their congregation, compared with only 33 percent in metropolitan areas. Why? It is probably because they see one another not only on Sundays but also during the week.11

In addition to the fact that congregations forge bonds among their own members, they also serve as bridges across the wider community by sponsoring broader events open to the public. These activities are especially common in smaller towns of five hundred to a thousand. In one town of this size, for instance, several people note that there is a fundraiser or benefit dinner for the community at least once or twice a week. One woman says with some pride that it is possible to get a wonderful home-cooked meal for five dollars at these events. In another town, the Catholic Church’s bingo night with all the popcorn you can eat is a popular attraction for Catholics and Protestants alike. In some communities, the churches actually seem to compete with one another in sponsoring events for the entire public. In others, the church leaders say they are trying to keep up with school activities that would otherwise draw people to ball games. Examples include churches renting the high school auditorium for a guest musical performance or hosting a town festival during homecoming week.

Although school activities may pose the most common source of competition for churches, another source that townspeople sometimes mention is the availability of attractive recreational activities, such as boating, fishing, gardening, and playing golf. This may be the reason for the pattern shown in figure 7.4. Average weekly church attendance is lower in areas that rank highest on the natural amenities scale than in areas that rank lowest. Generally, attendance declines as amenities scores increase. Attendance, however, is higher in small nonurban towns than it is in large urban towns at each level of the amenities scale. And attendance is highest in small nonurban towns located in areas with the lowest amenities scores.12

Figure 7.4 Attendance by town size and amenities

OF LIFE AND DEATH

Social scientists have long observed that modern society insulates itself from having to think very often about illness and death. Hospitals and nursing homes segregate the dying from the wider community. Funeral homes are tucked in out-of-the-way places far from the shopping malls that residents visit regularly. Churches are the one place where births, deaths, and illnesses are regularly acknowledged. Praying for the sick, hosting baby showers, and holding memorial services are part of the routine. Even in churches, though, the grim realities of life are sometimes shielded from view. Happy uplifting praise choruses substitute for paeans about suffering and solitude. Residents of small towns insist that things are more traditional there. Deaths, farm accidents, a boy drowning in the local lake, a teenager killed in an automobile crash, a mother struggling with breast cancer—these are harder to hide from in a small town. News travels quickly. People see one another at the grocery store. The family affected includes people they know. The churches provide a patterned way of responding. “If you have a death in the family, people stop by and bring food over,” a resident explains. “When my father and mother passed away,” another says, “they didn’t live here, but food was brought to us, memorials were given, people stopped by and just expressed their sympathy.”

In large suburban communities, church members experience similar expressions of sympathy within their congregations or neighborhood Bible study group. The difference in small towns is that when illness and death occur, faith transcends particular congregations. A vivid example is the story that a man in a prairie town of two thousand tells. His daughter, the youngest of four children, was born hydrocephalic. The doctors determined that she was educable, although she was paralyzed on one side and half her brain was atrophied. She went to kindergarten and first grade, but died just before her eighth birthday. The Presbyterian Church that the family attended was extremely supportive. But what the man recalled most clearly was how supportive the Catholic Church was. So often in towns like his Catholics and Protestants went their separate ways, sometimes perpetuating generations-old doctrinal animosities. In this instance, however, the death of an eight-year-old girl bridged the gap. The man was impressed with Catholics’ respect for life and understanding of suffering. He recently threw a birthday party for the priest, now retired, who became his closest friend.

Another important connection with death and suffering in small communities is established through the liturgical calendar. In his rich ethnographic study of a rural village in England, Michael Mayerfeld Bell observes that awareness of life and death was kept in the villagers’ minds through constant references to the cycle of nature.13 This is true in many small towns in the United States as well. Harvest festivals, roadside stands selling sweet corn and tomatoes, and maypole dances are examples. The churches participate as well. “There are lots of Bible references to sowers, to seed, and growing,” a pastor in a farming community says. He makes frequent use of these references in his sermons. “We talk about the difficulties of trying to raise crops during droughts and have lots of prayer requests along those lines. People in farming understand that.” On Sunday mornings one can hear hymns about seedtime and harvest, bringing in the sheaves, or gathering at the river. The message is that life is filled with ups and downs. Like the seasons, much about life is not within human control.

CARING FOR THE COMMUNITY

Lucille Pulliam wanted a better life for her three children. Soon the oldest would be in high school. In the city where they lived, drugs and gangs were a constant threat. The monthly rent took most of her meager income. Like a growing number of people living in poverty, she was intrigued by the possibility of moving to a small town where housing was cheap and crime was low. A foreclosed house was being auctioned for taxes in a town of thirty-six hundred an hour away. She bid, won, moved, and found a job. But she had nobody to fix it up. It turned out that the house was in such poor condition that it should have been condemned. Somehow the pastor of the Methodist Church learned of her plight and asked the six-member ministerial alliance at its next meeting if they thought the town’s church people could help. Over the next six months, people from all the churches got together and basically redid the house.

The remarkable thing about this story was not that the church people pitched in to help a needy neighbor. They were used to doing that for one another. It was rather that they were willing to help this particular woman. People in the community were wary of newcomers who were there simply because housing was cheap. These newcomers were known as the type who “want to sponge off the system,” as one old-timer put it. That was anathema in a town that prided itself on its work ethic. Even though Mrs. Pulliam had a job, people wondered if she would keep it or would soon be on welfare. Had it not been for the church connection, they likely would have done nothing to help. The ministerial alliance made the difference. Its imprimatur said in effect that this was a legitimate case for Christian charity. It helped, too, that the Baptists and Presbyterians did not want to be outdone by the Methodists.

Cooperative programs like this are not uncommon in small towns. They sometimes date to the town’s earliest years when fledgling congregations helped each other get started and often shared the same building for a time. Ministerial councils became popular during the first quarter of the twentieth century, and frequently continued through informal arrangements involving joint worship services, jointly sponsored holiday festivals, and community projects. In small towns with declining populations those traditions are again becoming more important.

In a town of about five hundred, as one example, the Christian, Presbyterian, and Methodist congregations merged a few years ago to form a single mainline community church, thereby leaving one evangelical Protestant church and the Catholic parish, which shared a priest from a town thirteen miles away. In a community of this size it was already common for churches to hold get-togethers because people knew one another as neighbors. The Catholic Church, for instance, sponsored a tea every so often for ladies from the Protestant churches. Sometimes it was a salad luncheon. One of the Protestant churches puts on musical programs for the whole community. “We go over there for fellowship,” a Catholic woman says. “You know everybody, so it isn’t like you’re afraid to go there.”

Besides cross-denominational church socials, cooperative projects to help families in need are fairly common. “All the churches get involved,” says Mr. Parsons about an annual project in his town of nine hundred. “We’ll find a family in need of house repair. It might be as simple as cleaning the gutters or something larger like painting a house. If it’s a large project that might take two or three different weekends, we assign each church a time.” Besides spreading the work around, what makes these programs successful is adapting them to the particular needs of different communities. Whereas food pantries, Christmas baskets, and Thanksgiving dinners for the needy are fairly common, other programs reflect greater creativity. One of the more interesting cases is a rural community of sixteen hundred that includes widows and single mothers with little knowledge of automobile maintenance, but farmers and mechanics with such abilities. The ministerial alliance paired need with skill by organizing a “car ministry” consisting of free oil changes and car washes one Saturday a month.14

The cooperative relations among churches may be changing, though. In many of the towns we studied, independent fundamentalist churches had emerged since the 1980s and become a significantly greater influence relative to old-line churches, such as Methodists, Presbyterians, and Lutherans. Community leaders in some of these towns said the result had been less cooperation across denominations. Some attributed it to fundamentalists’ tendency to adhere to strict distinctive beliefs that separated them from other churches. “We would almost be giving the idea that the teachings of the other churches are of equal weight to what we are teaching,” one fundamentalist pastor said in explaining why his church did not participate in community services with the town’s other churches, “and we don’t believe they are.” Other pastors said there was simply a more competitive sense among churches than there had been in the past. It may have been the result of pastors at independent churches needing to work harder to attract and retain members. It may have been simply that pastors were working such long hours among their own members that they had little time left for community-wide activities.15

This trend toward more conservative churches, compared with the historic influence in small towns of mainline Protestant churches and Catholic parishes, is part of a larger phenomenon observed frequently in studies of US religion. National surveys show that mainline Protestants significantly outnumbered evangelical Protestants in the 1970s, but in more recent years have dwindled in comparison. In these surveys, the proportion of residents in small towns that belonged to mainline Protestant denominations fell from 38 percent in the 1970s to 20 percent since the start of the twenty-first century. During the same period, the proportion of smalltown residents holding membership in evangelical denominations increased from 29 to 34 percent (Catholics held steady at approximately 20 percent, as did members of historically black denominations at 8 percent).16 Among the people we talked to, a majority belonged to Catholic or mainline Protestant denominations, but there were also members of evangelical denominations, such as Southern Baptists and Assemblies of God, and independent fundamentalist and charismatic churches with names such as Courts of Praise, Revival Tabernacle, Covenant Promise, and Living Hope. These members were quite dedicated to their fellow believers, but varied in the extent to which they were connected to other churches and community organizations.17

Even among members of well-established churches we encountered instances in which loyalties to the congregation were in tension with other churches or the town itself. A Catholic woman we talked to described feeling “out of it” in high school because most of the other students in town were Protestants. She often had activities at church that conflicted with events at school. Others reported similar experiences. One noted that his church did not approve of dancing, which left him out of the high school’s most popular weekend activities. Another said her family did not have a television because of the morally questionable influences they feared. That made her a laughingstock among fellow students. Among adults, tensions between church and town sometimes occurred over theological disputes. One resident recalled an incident that split her church and strained relations with townspeople who could hardly avoid seeing one another on the street. She figured that in a larger community, it would have been easier for people simply to go their separate ways. Pastors and priests reported conflicts arising from misunderstandings about zoning and church maintenance. It was not uncommon for ill feelings to divide communities when church memberships coincided with ethnic and kin networks. In those instances, German Catholics or Swedish Lutherans would mention that it was still difficult to marry across religious lines or conduct business together. Those divisions were more evident in smaller towns than they likely would have been in larger places.

Whether they are performed cooperatively or by single congregations, many of the caring activities in small towns have become routine, such as sponsoring a food pantry or deacon’s fund. One of the pastors we met described a food pantry that purchased bulk groceries from a state-run food bank and had been operating for decades through regular donations from families at his church. Another pastor mentioned a Vietnam veteran who needed gas money for a doctor’s appointment. The pastor phoned the gas station and told them to charge the purchase to the church’s discretionary fund. He said heating oil in the winter was a common request.

Although caring activities were routine, they were frequently stretched thin in communities with low wages and high unemployment. This was especially true when a mine closed, a factory shut down, or a crop failure occurred. Families scraped by, helping each other in small ways and only turning to the churches as a last resort. “How can you get by?” a priest in a town where the mine had closed asked a member whose husband had been out of work all winter. “Well,” she said, “my parents will call us up and they don’t want to make us feel bad, so they’ll say, ‘We made a bit too much food. Can you please come over and share some of it with us?’ ”

We also learned about creative ways of helping that reflected the special skills and needs in small towns. The Methodists in one community where farming and construction work were prominent purchased a rundown house for next to nothing, fixed it up, and made it available rent free on a short-term basis for families that may have lost their homes because of foreclosures or natural disasters. In another town that was too small to have a separate Alcoholics Anonymous organization, the adult Sunday school class at the main church started fulfilling the same function. As people began to open up, it turned out that nearly everyone was affected in some way personally or by a family member with an addiction. Other examples included church people in rural communities helping sick members plant or harvest crops, and there were still some instances of old-fashioned barn raisings. It was almost funny, a middle-aged farmer laughed. Her husband was so independent that he tried twice putting up a barn alone, and both times the wind blew it down before it was finished. At that point, their small church of about fifty people decided to step in and put up the barn whether he liked it or not.

In the smallest towns, churches are sometimes the only places in which civic functions can be held—another way in which churches serve their communities. The Methodist Church we encountered in one small community is the only building in town that can accommodate the town’s entire population of around 150 plus an equal number of out-of-town visitors. That makes it the location of choice for any funeral that draws a sizable crowd. It is also the venue for the annual harvest festival along with a moneymaking dinner and craft sale that attracts farmers and tourists as well as townspeople. The local residents who are not Methodists include Catholics, Lutherans, and Presbyterians who drive to other towns for church, but they work shoulder to shoulder with the Methodists to put on the harvest festival and host dinners after funerals. The Methodist pastor is a member of the city council and serves on a community improvement committee that is attempting to turn the vacant schoolhouse into a community center. Church members drive fellow members and other neighbors to the doctor when their help is needed, check in on neighbors who may be ill, and host benefit dinners at the church if a tragedy befalls a local family. If it were not for the church, these activities would probably diminish.18

Where emergency fire and rescue services are limited, as is true in many towns, churches are also likely to play an especially important role when disaster strikes. In a town of twenty-four hundred, as one example, a flood shut down the electric grid, and the town was left without its pumps to provide water plus had no cable television service. “People in the outside world,” a resident recalled, “knew more about what was happening here than we did.” The mayor was faced with the challenge of getting information to the community about what to expect, and what steps they should take to protect themselves and their homes. One of the churches had been working on a plan to do door-to-door evangelism. The pastor, in cooperation with other pastors, volunteered to organize a door-to-door information campaign using the same plan. They divided the town into “care pods,” worked up an information sheet, and canvased the town, telling people how to take care of themselves. They repeated the effort daily for a week until the electricity and water supplies were restored.

Pastors and lay members naturally are eager to tell heartwarming stories about times when their congregations have made a difference in the community. Unfortunately, the picture is not always this positive. Declining membership, loss of population, and depressed economic circumstances in small towns can discourage civic involvement rather than motivate it. Consider the experience of four churches in a southern town of six hundred. The Assembly of God Church shut its doors for lack of participation, the white Baptist Church had no interaction with the African American Baptist Church, and the Methodist Church was basically in survival mode with about forty-five members and shrinking finances. Although efforts had been made earlier in the town’s history to form a ministerial council, each of the churches went its own way. There were no joint services or cooperative programs. The downtown area was completely boarded up. Farming in the area was depressed, and a mine that had previously provided some employment had closed. The only remaining employer was the public school, and it was struggling. Each of the three pastors tried at various times to initiate after-school programs, tutoring, and other activities for children, but none was successful. Even getting the church members to come to anything besides Sunday morning services proved difficult. “They just had other things they felt were more important,” one of the pastors explained. “About the only thing they would come out for was a football game.”

CHURCH CONFLICTS

In her study of congregational conflicts, sociologist Penny Edgell Becker found that disagreements emerge and escalate over the smallest incidents. A pastor visiting one family and failing to visit another when someone is in the hospital can trigger lasting resentment. Church people notoriously fight over hymns they do or do not like, and whether the organ should be at the back of the church or the front. Conflicts, Becker discovered, were more severe when a congregation was already losing members, struggling with finances, displeased with the pastor, or failing to meet the expectations of a growing community. These were common issues in the suburban churches she studied. In a subsequent study conducted among congregations in upstate New York, she found that family issues were especially important. Although her study did not focus on church conflicts, the congregations in these smaller rural communities were especially oriented toward ministries involving families with children, and this emphasis increased tensions that arose periodically over questions of homosexuality, abortion, and gender roles.19

Like so many aspects of small-town life, church conflicts have been the grist for humorous accounts that illustrate the old-fashioned and sometimes-wise common sense that prevails in these settings. One of radio entertainer Garrison Keillor’s Lake Wobegone monologues describes a rural Lutheran church that split over the question of whether women should be ordained. Those opposed said women’s ordination was against God and contrary to scripture. They would have left and formed a new church, but the church they belonged to controlled the cemetery. They wanted to be buried there alongside grandma and grandpa. So they stayed, and when the congregation called a woman pastor, the only pastor who would come, they decided, what the hell. It may be contrary to the Bible, but we like her.20

Although clergy and lay members who actually live in small towns usually portray their congregations as caring communities, conflicts do occur—indeed, a quarter of pastors in rural churches reported a conflict causing some of their members to leave within the past two years, according to one national study, or the same proportion as in urban or suburban congregations.21 When conflicts happen they can be devastating, particularly in smaller places where people see one another regularly and possibly have few other church options. Disagreements within and between extended families are one of the most common sources of tension. At one of the churches in our study the pastor described an incident between two men, one of whom accused the other of saying something insulting to the first man’s wife. The accuser left the church over the incident. That was more than a decade ago. He has never returned, even though he still lives in the community. Having no other local options, he and his family drive to a town half an hour away to attend church.

As another case in point, the pastor of an evangelical church in a town of about a thousand told of an incident several years before he arrived that nearly destroyed his congregation. The church operated a state-accredited elementary school for about fifty of the town’s children, but enrollment was dwindling and the accreditation standards were stiffening. Amid these difficulties, the pastor at the time became discouraged, left, and the school closed. Most of the families with children left the church and have never returned. The current pastor says it is almost impossible to attract any families with children.

The tension was even more severe in another town with only one congregation. Members took different sides toward the denomination’s position on homosexuality. Half thought the denomination should do more to welcome gays and lesbians into full membership, while the other half were adamantly opposed to anything that might encourage or legitimate what they viewed as a wicked lifestyle. The latter half pulled their membership from the congregation, stayed at home on Sundays, or drove to another town. But in a town of fewer than two hundred people, it was hard for the two factions to avoid seeing one another. It was awkward to run into someone at the café and not feel like speaking to them.22

Because churches are located in small communities, it should not be assumed that conflicts are more acute than in other locations. We found plenty of instances in which people remembered intense conflicts and yet by all indications had put them to rest. At a church of fewer than two hundred in another small town, the congregation had divided into two warring factions over the church parking lot—one side wanted to pave it, and the other did not. Both sides became quite outspoken in defense of their view. But when the pavers won by a narrow vote, the opposition accepted the decision and nothing further was said. That was true in other situations as well, such as conflicts about plans to replace or renovate the church building, and decisions to hire a new pastor.

Two aspects of these controversies were key to their being resolved. The first aspect was when neither side regarded the issues as fundamentally about biblical interpretation or moral principles but instead about budgets, relationships, and families. In that sense, the concerns were important, yet they were different from questions about abortion, homosexuality, or whether to oppose or support some major theological policy of their denomination. And second, the small-town ethic of keeping one’s mouth shut kicked in. Members knew that if they were going to continue living in the same community, seeing one another at the post office and shopping at the same grocery store, there was a time to quit fighting.

In towns of three to five thousand or more it is not uncommon, though, to find churches that have emerged because of splits in older established congregations. In a town we visited that had fewer than four thousand residents we noticed there were two Methodist churches five blocks apart. They were among the twenty congregations in this small community. Why was there a need for two Methodist churches? “Congregations start fighting,” one of the pastors explained. People say, “Well, you know, this is important enough to me that here is where I stand, and if you don’t see it that way, we’ll go start our own church.” The second Methodist Church and several of the other local congregations had begun that way. In another town the thousand-member population was served by eight churches, two of which were small Pentecostal congregations in makeshift buildings located, respectively, at the opposite edges of the community. Judging from their names, it appeared that one favored more direct revelations from the Holy Spirit than the other. But a longtime resident explained that the pastor of the older congregation had an affair with a woman in his congregation in the 1990s, precipitating the split, and half the members left to start the new church.

Sociologists of religion view congregations forming because of disputes in established churches as an example of the religious market-place.23 Religion flourishes, according to this interpretation, when competition exists among churches and when congregants are free to choose some other church, or start a new one, if the spirit moves. There is plenty of evidence that competition of this kind is present, even in small communities. One church adds a new educational wing, and pretty soon another church renovates its sanctuary. Less often noticed in the academic literature, though, are the efforts that church leaders make to suppress overt competition.

In small communities it is important for clergy to get along with one another, just as it is for lay members of different congregations. Clergy face the prospect of seeing one another at the bank and football game, and may anticipate having these regular interactions for years. It does Pastor Smith no good if he and Pastor Jones cannot get along. To keep strained relationships from happening, pastors find ways to work together despite differences in liturgical style and theological interpretation. A striking example is evident in a rural community of less than a thousand in which there are seven churches, including Catholics, mainline Protestants, and evangelical Protestants. Although there are significant doctrinal differences and occasional incidents of members of one church defecting to another one, the pastors have a ministerial association that maintains good relations among all the churches in town. It helps that they have a common commitment to serving the community. Behind the scenes, the pastors take turns being on call with the sheriff’s department in case an accident occurs, or a family needs gasoline or a place to stay overnight. The community’s Thanksgiving and Good Friday services are jointly sponsored. Whenever one church hosts a concert, guest speaker, or some other special event, the pastors usually advertise it as a ministerial association event just to show that one church is not trying to outdo any of the other ones.

The perennial criticism of small churches in small towns, including among members themselves, is that they become so focused on their own needs and interests that they lose sight of the wider world. Although watching television, traveling, and having relatives in other places mitigates this insularity, the churches believe they have an obligation to expand their horizons. The gospel mandate to spread God’s love beyond Judea, as the Bible says, to Samaria and the uttermost ends of the earth requires a wider vision. Large churches in cities and suburbs can more easily do this. Their size makes it possible to hire special global ministries staff, and members may have business contacts abroad. Still, it is notable how many small congregations in small communities have established links to the wider world.

In town after town, we found small churches with ties to other countries through members and former members who had become missionaries and international humanitarian workers. These links are present even in the smallest rural congregations. A Baptist church with only twenty-five regular members in a town of eight hundred had connections with a ministry in Brazil because of a man who had grown up in the church and gone there as a missionary. The church not only supported him financially but several of the members also went on occasion to help for a week or two with the ministry there. In rural communities, farmers whose work was seasonal were often the ones who participated in such trips. Residents with skills in construction, teaching, and health services were also among the volunteers. In another town, the Catholic Church had sent several missionaries to Brazil and had kept in close touch with them over the years. These connections with homegrown missionaries depended on family ties, but formalized links have also become more common.

“Recently one of our ministers went to Tanzania and lived there for three months,” a Lutheran member in a remote farming community of fifteen hundred says. She appreciated learning about churches in Tanzania from the minister’s sermons. Her experience was similar to the members of a Lutheran church in an even smaller community whose pastor had served as a short-term minister in eastern Europe and frequently reported to his members about conditions there. In a town of twelve thousand where separate weekly masses were conducted in English and Spanish, a visiting priest from India provided information about his home parish and raised money for the ministry there. At a nondenominational church in another community, the pastor had done evangelistic work on several occasions in Central America and Africa. He was trying to instill a global perspective among the youths in his congregation. In other instances, pastors were among the few in their community who had ever traveled outside the United States. The pastor of a mainline Protestant congregation in a town of twelve hundred, for example, had been to the Soviet Union during seminary. The trip left him with a continuing interest in peacemaking and international social justice.

A second connection occurs through denominational programs. Catholics, Methodists, Lutherans, Southern Baptists, Presbyterians, Assemblies of God, and smaller denominations all have international evangelistic and humanitarian aid ministries in which the smallest congregations participate. These programs provide information about needs in other countries or other parts of the United States, and facilitate opportunities to be of assistance through financial gifts, donations of food and clothing, and volunteer time.

An example is the United Methodist Committee on Relief. Following the 9/11 attacks on New York City and Washington, DC, the committee was one of the first relief organizations on the scene. That was true as well when Hurricane Katrina struck New Orleans, a tsunami devastated Southeast Asia, and a massive earthquake took place in Haiti. Members of Methodist churches in small towns far from any of these locations were able to assist financially and by sending volunteers. Besides responding to emergencies, churches worked with denominational agencies to develop longer-term arrangements. At one congregation, for instance, a relationship with a mission church in Haiti involved filling boxes with toys, supplies, and mosquito nets, regular correspondence, and periodic visits. This had been happening for almost forty years.

Other congregations were involved in similar programs through Catholic Relief Services and Lutheran Social Services. It seemed especially important to members of these congregations to feel that they were crucial participants in the larger programs. A lay member at a Lutheran church in a town of twelve hundred says he and a few other volunteers from the congregation go to Africa once a year to help with an educational program. “You’re living out here,” he says, “and you just have that feeling of, well, that you’re doing something to help on a grander scale.” In another rural community, members of the Catholic parish took special interest in a partner parish in Kenya with which they exchanged news, letters, photographs, and emails.

A third international tie occurs through short-term mission trips. These connections are facilitated by denominational and interdenominational agencies that specialize in such ministries, but they also require the initiative of a local leader. A church member in one small town, for instance, mentions “a hometown boy who is an itinerate speaker with an international ministry,” and says that the town still serves as this man’s “home base” and helps him with financial support. The same congregation participates in short-term mission trips to Mexico. Each year, two or three teenagers or young adults join a group organized with other churches in the region to spend several days in Mexico doing volunteer work. “It just opened their eyes,” the pastor says, “to the fact that we are a blessed people.”

These programs are seldom cheap. A short mission trip to Peru can cost as much as seventeen hundred dollars just for airfare, not to mention the time involved in organizing the trip. Pastors and lay leaders in economically depressed areas say they have had to rethink their priorities and find less expensive ways to be involved in the wider world. They drive to Mexico instead of flying to Peru or do volunteer work in a US town hit by a natural disaster. The people involved nevertheless feel they have been able to serve and have had their horizons broadened as a result.

Leaders say that good communication and careful planning are the keys to a successful program. One of the clearest examples of good planning happened when a church was destroyed by fire in a small southern town. Needing outside assistance to rebuild, the members got together and poured a concrete slab to serve as a foundation for a new building, and then scheduled two workdays for volunteers coming from several states to construct a prefabricated building. Information about hookups for volunteers’ recreational vehicles was posted on a Web site along with tool needs and arrangements for meals. In another community, a retired pastor regularly visits churches in a half-dozen surrounding towns to collect clothing and small household items, and then drives a van loaded with the material to churches in central Mexico. Each summer lay volunteers from the US churches spend a few days in Mexico providing tutoring and health screening. As much as the help is needed in Mexico, the benefits accrue more to the US volunteers, who gain a different perspective on their own lifestyle and faith. That may be especially critical in small towns. “When you’re in a small town,” one pastor explains, “you seem to think small and maybe even feel insignificant.” But being involved in projects in another country or even in another part of the United States, he says, “lets you see from a broader perspective that you are significant.”

There is also an emerging international connection in many rural communities through immigration. In a town of ten thousand that had been predominantly white Anglo, for example, more than a quarter of its population is now Latino or Asian American. The change has happened because a large meat-processing plant opened in the community in the 1990s. The influx has caused churches there to initiate Spanish-language services and provide temporary housing for immigrant families. In another town, an Anglo woman who learned to speak Spanish in college and figured she would have no use for it is now working with Hispanic immigrants in her community. Her interests in cross-national ministry had been sparked in high school when she and her sister along with their dad spent three weeks in Mexico working at an orphanage affiliated with Mother Teresa’s Missionaries of Charity. That trip led her to return to Mexico another summer to work at a home for boys. She says these experiences in high school opened her eyes to what was going on in other countries and helped her know what it was like to be a foreigner. They also deepened her interest in human rights. Although she lives in a safe community that has not changed much in a hundred years, she is keenly interested in human rights issues facing people in places like Darfur.

A national survey suggests that international connections like these may be fairly typical of small communities. Among active churchgoers who attended congregations in small towns or rural communities in non-metropolitan areas, 39 percent said their congregation had sponsored a short-term mission trip to another country during the past year, 40 percent said their congregation had hosted a speaker from another country, and 50 percent claimed that at least a few of their fellow church members were recent immigrants. Other connections were even more common. Three-quarters said their congregation had taken up a hunger relief offering in the past year. Three-quarters also said their congregation had helped to sponsor one or more foreign missionaries.24

Mission trips and partnerships with congregations in other countries broaden perspectives in a way that merely watching news on television seldom does. A vivid example occurred at a Catholic parish of five hundred members in a town of about five thousand that learned of a priest in Central America who was seeking to establish a partnership with a North American parish. The Central American priest was serving fifteen rural villages, rotating among them over a two-month cycle. The area was extremely poor and badly in need of medical assistance. The US parish sent a medical team. It proved to be an eye-opening experience in more ways than one. During the trip the team’s vehicle broke down, forcing the group to walk an hour and a half through driving rain back to the nearest town. On arriving, they learned the mountain road had washed out and they likely would have been killed had their journey continued. Shortly after their return, news came that their interpreter had been murdered.

CHALLENGES FACING SMALL TOWN CONGREGATIONS

Barbara Raines is the pastor of two Methodist churches twelve miles apart. One is in a town of thirty people, and the other in a community of fewer than two hundred. Both towns have been losing population—a trend that has been going on for more than fifty years. Farms in the area have grown larger and fewer, the railroad is gone, and businesses and schools have closed. Only a trucking company, fertilizer plant, couple of beauty shops, and bank are left. The larger of the two congregations averages thirty-five to forty regulars, and the smaller one never exceeds twenty. Rev. Raines preaches a 9:30 a.m. service each Sunday at the smaller one and an 11:00 a.m. service at the larger one. There are few young families or children at either church, and in recent years more of the aging members have been moving to a nursing home in a larger town twenty miles away. The obvious question, one that even the Methodist district superintendant asks, is why the two congregations do not consolidate. The commute from one to the other is an easy fifteen or twenty minutes along a paved road. But neither congregation is willing to shut down. In fact, a few years ago the smaller congregation was down to ten members and in such poor financial shape that it seriously considered closing, but members started a newsletter, canvased their neighbors, and kept the congregation going. Both churches have their own buildings and are the only congregations in their respective towns.

This is a pattern widely evident in rural America. Methodist circuit riders started churches by the thousands during the nineteenth century as the frontier expanded. Baptists, Catholics, Disciples of Christ, Presbyterians, and other groups started churches in many of the same locations. The practice was a good one. When frontier towns died—as many did—for lack of rail service, drought, fire, or failing to be selected as a county seat, the fledgling churches in those communities closed, while the ones in towns with rising populations flourished. Over the years, nearly every small town came to be the location of several churches. Yet the decline of population that began in the 1920s in many small towns, and that continued through the twentieth century, left churches that were too small to support themselves and yet were reluctant to close. They had a building and cemetery that commemorated the history of the community and its families.

Rev. Raines illustrates one arrangement that has played an important role in staffing small declining rural churches. She is in her early seventies and a widow. Her husband was a Methodist minister. During his career, he had worked his way up from small churches in small towns to a choice position in a community of fifty thousand that was one of the larger towns in the district. Although it was customary for Methodist clergy to be assigned a new location every three to five years, the district superintendent kept him in this community for twelve years. Like nearly all pastors’ wives, Mrs. Raines had always been an active lay volunteer in her husband’s congregations. During the twelve years in this community of fifty thousand, she served as youth coordinator for all the Methodist churches in the district and a Sunday school teacher in her local congregation.

With only a high school degree, there was no way Mrs. Raines could go to seminary and be ordained as a regular paid clergyperson. The denomination, though, had always included a provision through which laypeople could become unpaid local pastors and serve in congregations staffed by occasional visits from regular clergy. A recent provision that pertained to Mrs. Raines was that anyone past a certain age, usually fifty, was not required to attend seminary full-time to receive a license but instead could attend classes from two weeks to a month in duration and accumulate sufficient credits over a five-year period. It was through this process that she became Rev. Raines and was hired as a youth minister. After serving in that capacity for nine years, she and her husband were moved by the district superintendent to a small congregation in a town of fifteen hundred. She did not work, and after two years her husband retired and they moved to another state to be near their children. Her husband began preaching again almost immediately, and they decided to return to the state where he had spent most of his career. He filled vacant pulpits for five years, including the two that his wife now has, and when his health made it impossible to continue, she took his place. Since his death five years ago, she has served full-time at the two congregations.

The parts of this story that are representative of broader trends in small communities are that Rev. Raines is an older woman and earned her license as a pastor later in life. It is also increasingly common for pastors in small communities to serve more than one congregation, and for husband and wife teams to serve as copastors, or one to be paid and the other to be an unpaid volunteer. These arrangements have made it possible for small congregations to remain open. In most instances, younger clergy intent on working their way up would not find small congregations like this attractive, but for older clergy who may have family ties in an area and be interested in a slower pace, one or two small congregations in small towns can be attractive. As another example, a woman who pastors two rural Lutheran churches in a similar context but in another state says she is happy to be able to serve these congregations because both are within a few miles of the farm she and her husband own. She went full-time to seminary, but only after having held other part-time jobs and doing volunteer youth ministry work while her children were growing up.25

Catholic churches in small rural communities have adapted to sparse populations and a scarcity of priests by closing parishes, shutting down parochial schools, delegating more of the routine administrative tasks to lay volunteers, relying on immigrant priests, and asking priests to serve more than one parish—a pattern called clustering. Father Tom Malone is currently serving in one of these clustered arrangements. Although he could have served a larger urban parish, he says he preferred a smaller place where he “could be a bigger fish in a smaller pond.” He lives at the rectory in a town of eighteen hundred, serving the parish there and commuting to two other parishes in neighboring towns. The three parishes include approximately five hundred families. Members have become accustomed to not having a full-time priest in each parish, but Father Malone says the adjustment has not been easy. For years, parishioners went to Mass at the same hour each Sunday. Now there is a rotating system that keeps people on their toes. If they prefer to worship in their hometown, they may have to attend on Saturday evening instead of Sunday morning, of if they prefer Sunday morning, drive to another town. The decisions about schedules and locations have been accompanied by some resentment as well as frustration. “This community feels very hurt,” Father Malone says. “Their priests have been taken away from them. The people do not feel valued or appreciated.”26

Declining population and economic setbacks also force congregations to postpone repairs to church buildings, scale down programs, freeze or reduce pastors’ salaries, and require pastors to rely more on spouses’ income or second jobs. “My family has felt the pinch very hard,” the pastor of an evangelical congregation in a declining town of a thousand says. His story is not atypical. Prior to becoming a pastor, he had been in secular employment and took a huge pay cut to enter the ministry. Five years ago his move to the present location involved another salary reduction, and he has not had a raise since then. The church shut down a radio program it used to cosponsor on a Christian radio station in the area, cut back its community-wide programs for children by 50 percent, and has not replaced a worn-out lawn mower or broken video projector. The pastor has taken a second job as a clerk in one of the town’s few remaining stores. The difficulties have partly been caused by a drought that has hurt agriculture-related incomes and business in the region. The trouble also illustrates small congregations’ vulnerability to population shifts. The congregation lost twenty-six members in one year. Several died, others moved away because of health or a loss of jobs, and still others grew disillusioned and switched to a different church in town. “When you lose people like that, it obviously has an economic effect on the church,” the pastor says. “It also has a psychological effect. You are friends with these people, and they are suddenly gone. That’s a hole in your life.”

Church closings in small towns are difficult for many reasons. In some of the towns we visited, the churches were doing fine financially—usually because of a few families who supported the congregation generously—but were too small to attract a pastor. Members were often proud of the building that they and their forebears had lovingly maintained. They hated to see the building empty, torn down, or put to other uses. In other towns, the threat of a church being shut down seemed like a slap in the face to the remaining members. They knew the decision was in the hands of a bishop or regional board, but could not help feeling betrayed.

Perhaps because it is difficult to completely shut down a church, it is more common for churches to shrink in membership than to actually close. This tendency is evident in county-level data collected nationally in 1980 and again in 2000. In counties where the population grew or at least remained stable during those two decades, the total number of church adherents rose at a higher rate (29.5 percent) than the total number of churches (17.2 percent). In other words, congregations on average became larger. The pattern was different in counties that lost population. In counties experiencing minor population loss (that is, a decline of less than 1 percent per year), the total number of church adherents dropped by 11.2 percent, but the number of churches declined by only 0.8 percent. And in counties with major population loss (a decline of more than 1 percent per year), the total number of adherents dropped by 23.2 percent, but the number of churches fell by only 9.4 percent (see figure 7.5).27

Figure 7.5 Change in churches and adherents

Although church closings in declining areas are relatively rare, and undoubtedly influenced by many considerations, one aspect of the local social circumstances that matters is the number of towns in the immediate vicinity. Taking account of differences in total county population, the data collected in 1980 showed that the number of churches per county was larger when there were more towns in the county. That made sense because historically the founding of churches usually went hand in hand with the founding of towns. In fact, the 1980 data showed that each additional town in a county was associated with an average of 2.8 additional churches in the county, taking account of differences in the total population. But having more towns and thus more churches also meant that it was easier during the next two decades for churches to be closed in those communities—apparently because the remaining members could more easily travel to an adjacent town. Statistically, there was a negative relationship between the number of towns per county and the number of churches per county in 2000, taking into account the number of churches and the population in 1980. Each additional town in the county was associated with a decline on average of approximately 1.2 churches.28

If closings are hard for the members who lose their church, questions arise as well for the churches that remain. An example is a Methodist church in one of the towns we studied that had a population of about three thousand. As the county seat, the town’s population had been stable over the past quarter century, partly because more farmers in the area lived in town and partly because more of the town’s younger residents commuted to jobs in a city forty miles away. Countywide, there were nine other towns, only one of which had more than a thousand residents. All these towns were smaller than they had been a generation ago. The Methodist Church in the county seat had about 150 regular members, down from 200 in the 1980s. It was faring better than the four Methodist churches in neighboring towns, at least two of which were expecting to be closed in another year. The questions that the county seat church was facing included the prospect of welcoming new members when these sister congregations closed. Its members were mostly old-timers who had belonged to the congregation and made friends over a number of years. How would they respond? They would of course welcome new families. But they wondered if the new families would feel at home. Would they resent their own church having been closed? Would they be a clique that kept to themselves? Would they truly feel welcome? These were the issues that the county seat church was pondering.

A contrasting example—one that shows the possibilities for growth even in remote rural locations—can be found at the Central Mission Church, which is also located in a small community with a declining population. The town has no industry, and farmers in the area have been suffering from drought for the past seven years. Statewide the average age is thirty-five, but here it is forty-eight. The farmers’ sons and daughters nearly always move away, at least temporarily. The older generation hangs on to the farm because it has been in the family for five or six generations. The farmers hope that one of their sons will come back when they retire. In the meantime, they go to the church that their family has attended for decades. Most are Methodists, Lutherans, or Congregationalists. These churches are losing members and struggling to attract new pastors when one leaves. In contrast, Central Mission has been growing. Its membership is a hundred, up from fifty a decade ago when Pastor Frank Newland arrived. Today he is at the hardware store making a small purchase. A woman who usually attends another church but has visited his comes into the store. “I’m going to visit your church again one of these days,” she tells him. “We always love to have you,” he says. “God is in your church,” she says. “I go to my church and I like my church, but God is in your church. He shows up when you have church.”

“That was a great compliment,” Pastor Newland reflects later. He attributes it to the fact that his church is not just a country club but instead a place of genuine worship. But pressed to say more, he explains that it is the love the church tries to show that really matters. “We are a very, very economically depressed area,” he explains, “so financial concerns among our families are always an issue.” They are especially an issue for the families at his church. They are the poorest of the poor, the “riffraff” who are seldom welcomed with open arms by the established residents. They come because average housing costs are 70 percent cheaper than the state average. Indeed, it is not hard to find a vacant house that can be rented for next to nothing. The newcomers include abused women on welfare who are fleeing husbands and boyfriends in the city. There are jobless workers who came when times were better and have been unable to locate work elsewhere. Pastor Newland says there is a surprisingly high rate of turnover among the members at his church. The newcomers feel more at home than at one of the older churches in town, but then they move on or perhaps the husband does find a job, leaving the women and children behind. He says the financial strain on marriages is acute. Alcoholism is a chronic problem.