You Have to Deal with Everybody

The Inhabitants of Small Towns

BRIAN PARKER LIVES IN A rambling two-story house built in the 1920s. Out back there is a badly weathered garage that doubles as a storage shed, and to the south of that is a large garden with rows of overripe tomatoes and zucchini. Mr. Parker farms several acres of rented land a few miles from town, and he and his wife, Laverne, operate a small hardware store that serves the local population of four hundred. They are plain-spoken people who have a lot to say about living in a small place, if one is willing to listen.

When the Parkers moved here twenty-five years ago, the community was almost 50 percent larger than it is today. Farms in the area have become larger in acreage and fewer in number. Young people have moved away. Besides the hardware store, Main Street now serves as host only to a farm supply store that sells tractors and fertilizer, the post office, a senior citizens’ center, the branch office of a state bank, a coffee shop, and five vacant buildings. To see the doctor or purchase groceries (other than a few essentials), the Parkers drive fifteen miles to the county seat of fifty-five hundred residents. The county seat’s population has also dropped by nearly 50 percent since the 1970s.

Unlike most of their neighbors, the Parkers did not grow up here. They were raised in different suburbs of a large city two hundred miles away. After high school, each of the Parkers went away to college, graduated, and took jobs in another state. But Mrs. Parker’s grandparents lived in a small town and as a girl she reveled in visiting them. She especially enjoyed breathing the fresh air and seeing the nearby farms. When the Parkers’ first child was born, they decided they wanted to raise their family in a small town. They took the risk of leaving their jobs in the city, lived on as little as possible, and somehow made it work. Having lived in cities, the Parkers are keenly aware of how small towns differ. “We’ve reflected a lot on the differences between rural and urban life,” Mr. Parker says. “In the city, you tend to hang out with people who are of the same socioeconomic class that you are. Your friends and your relationships are, well, as they say, birds of a feather that flock together. In a rural community, you can’t do that. You have to deal with everybody. Rich people, poor people, farmers, veterinarians, accountants. You can’t retreat into a world of your own making.”

To understand how people in small towns view their communities, and how their communities shape their behaviors and attitudes, we must begin with the people themselves—people like the Parkers who have left the city to live in small towns and their neighbors who have lived in small towns for generations. In so doing, we confront an interesting irony. The millions of people in the United States who live in small towns are quite diverse. They vary in national background, race, age, family style, sexual orientation, education level, occupation, and income. At the same time, townspeople argue that they are not so different from one another. They see their fellow residents as similar to themselves: profoundly democratic, neighborly, and basically equal.

IN IT TOGETHER

The truth is that life in small towns is stratified, just as it is elsewhere in the United States. In their research on rural and small-town America in the 1970s, demographers Glenn V. Fuguitt, David L. Brown, and Calvin L. Beale found considerable variation in individual incomes, for example, with as many as two-thirds of white males in some towns enjoying standards of living above the national mean, while 12 to 16 percent of the population in nonmetropolitan towns were living in poverty.1 More recent data show that 1.1 percent of households in nonurbanized towns of fewer than twenty-five thousand people earn incomes at least five times the median amount. At the lower end of the spectrum, among residents in these towns, approximately 25 percent of households have incomes less than half the median amount.2

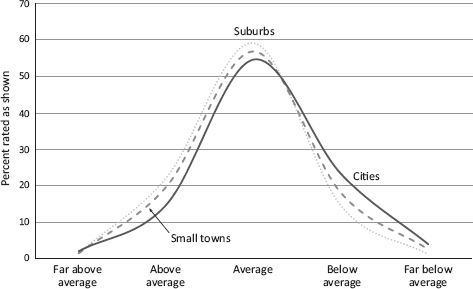

It is nevertheless the case that economic diversity is slightly lower on average in small towns than in larger places. As shown in figure 2.1, an index of diversity in which a larger value indicates a lower probability that any two households will fall into the same income category increases as towns become larger. Income diversity is especially low in the smallest towns, and diversity scores are approximately the same when all small towns are considered or only those in nonmetropolitan areas. Among the smallest towns, income diversity does vary considerably, though. For instance, the lowest income diversity occurs in towns such as Corral City, Texas; Hamer, Idaho; Kief, North Dakota; and Mildred, Kansas (all with populations under a hundred). In contrast, several small towns with larger populations—such as Kuttawa, Kentucky; Middleburg, Virginia; and Oxford, Maryland (with populations of more than six hundred)—have as much income diversity as many small cities.3

Figure 2.1 Income diversity by size of place

Ethnographic studies conducted in small towns between the 1920s and 1960s nearly always described status differences between the rich and poor, the powerful, and those lacking in power. The authors of these studies, however, were similarly struck by the frequency with which the inhabitants they talked to insisted that everyone was the same. For example, anthropologist Carl Withers, who wrote under the pseudonym James West, observed in the early 1940s that the residents of Plainville, a town of 275 people in southwestern Missouri, “completely deny the existence of class in their community.” They spoke openly of differences they had witnessed between rich and poor in other places, but declared with pride, “This is one place where ever’body is equal.” Similarly, when sociologists Arthur J. Vidich and Joseph Bensman studied Springdale, a rural New England community of 1,000 residents in the 1950s, they concluded that “we’re all equal” was one of the townspeople’s most important ways of characterizing themselves.4

It was common in community studies of that era to pass off residents’ perception of their basic equality as a kind of false consciousness. This understanding of their communities was rooted, scholars argued, in residents’ naive unwillingness to acknowledge local differences in social class, as the Plainville study suggested, or was masked by meaningful but superficial norms of local etiquette, such as exchanging greetings with passersby, as Vidich and Bensman observed. The task of social science, as practitioners in those decades understood it, was to bring to light the cold facts of social stratification that residents themselves may have been oblivious of or reluctant to acknowledge.5

A different perspective, though, is more useful for understanding the status differences and self-perceptions of contemporary residents in small towns. This view emphasizes that status differences do exist and are understood to exist by residents themselves, but that there are also expectations associated with these differences that contribute to the community well-being, and thus reinforce the sense of everyone being in it together. In other words, social norms exist in small towns that encourage feelings of solidarity despite differences in income and occupational prestige. How this works cannot be understood without paying close attention to what actually constitutes these status distinctions. While they are rooted in differences of income, education, occupation, and lifestyle, just as they are in cities and suburbs, they also reflect the different functional roles that people play in their communities—that is, roles such as doctor, teacher, banker, homemaker, wage laborer, or retiree. The result is a division of labor, as it were, that begins to tell us something about how small communities sustain themselves and why residents find these communities attractive. At least some of these status distinctions further reflect changes that have taken place in small towns in the decades since many of the earlier ethnographic studies were conducted.

One version of the division of labor present in small towns is evident even in fictional accounts, such as in novels and films. Depictions of small towns in these sources typically highlight stark status distinctions. Characters include town patriarchs who lord it over the rest of the community, families who live on the right or wrong side of the tracks, and individuals who are considered by the townspeople as outsiders or outcasts. Many of these contrasts are overdrawn, serving better for narrative purposes than as accurate descriptions of status differences. Yet they capture an important aspect of small-town life. In real life, residents do draw contrasts among themselves and place fellow residents in categories that mark status differences.

In Distinction, Pierre Bourdieu argued that social status cannot be reduced to simple measures of wealth or power but instead has to be understood in terms of the cultural dynamics that prevail in particular locations. These dynamics involve the deployment of symbolic boundaries that separate groups from one another both in self-perception and how they are perceived by other groups. The distinctions so drawn become part of the habitus—the taken-for-granted habits of life—that shapes individual behavior and social relations. As people carry out the daily tasks of ordinary life, they reinforce these distinctions. Some lines of demarcation, such as race under apartheid, are hard distinctions perpetuated through force as well as by custom, while others involve soft lines that are easily crossed and blurred. Status markers, in Bourdieu’s account, not only separate people but also reveal underlying social relationships that constitute the social order and bases of solidarity within communities.6

The marks of distinction in small towns in the twenty-first century reflect the familiar ladders of stratification that involve differences in income, educational attainment, and occupation. In addition, the major categories of distinction reveal important understandings about the expected relationships of individuals and families to their communities. At the top are the gentry who occupy positions of formal and informal power. The gentry play an important role in the economic and civic life of small communities. They are followed by two other groups, which make up the largest share of the population in most small towns: the service class and wageworkers. Pensioners, who include residents who are retired or semiretired, make up a fourth category, and there are always a few residents who cannot be classified in any of these categories.

The gentry seldom make up more than 2 to 5 percent of the overall population of small towns, which means that their numbers range from only a handful in the smallest towns to a few hundred in larger towns. They are distinguished by wealth, but also by reputation as prominent landowners, inheritors of old money, and people of influence.7 Beneath them, members of the service class have less wealth and influence than the gentry, but nowadays in even the most rural communities have often been to college, and are employed in white-collar and other middle-class occupations. They work at jobs that are popularly understood as valued services to the community and its residents, such as teaching, health care, government services, or in many cases, operators of retail stores and farms. Whereas the service class is salaried or depends on business income and investments, wageworkers typically are employed in hourly jobs, and usually have only a high school education or some vocational or technical training beyond high school. They work in small manufacturing plants, as office staff, as aides for teachers and nurses, in construction, and as farm laborers. Pensioners are retired and semiretired residents who depend on pensions, private savings, and Social Security for support. Interviews with individuals who occupy these statuses in small towns show what sets them apart from one another, but also reveal the bonds that link them together.

The landed gentry are well illustrated by Bud Janssen, a farmer who lives in a town of approximately forty-five hundred people populated by farmers and farm laborers, construction workers, and an ample supply of government employees, teachers, store clerks, and retirees. A row of cedars and tamarack separates the Janssens’ spacious ranch-style home from a county road that marks the edge of town. Beyond the road, huge fields of soybeans and corn stretch across the high plains for miles. The town was 20 percent larger in 1980 than it is today, having lost population as a result of farms in the area becoming larger. But there is an interstate highway nearby, and the town is a county seat, has a technical school, a radio station, and a hospital—all of which make it an important regional hub and mean that the community is in no danger of dying.

Today Mr. Janssen has just returned from clearing the remains of an abandoned farmstead on land he purchased several years ago. He used his own bulldozer, which he keeps with his fleet of tractors, combines, and cultivating equipment at a farm fifteen miles from town. On his way home, he detoured past another field, where he intends to plant millet in the fall. “I had to see what kind of weeds was growing and how soon they needed to be sprayed,” he says. Unless it rains tonight, he will be tilling a field twenty-five miles away tomorrow.

Mr. Janssen is a third-generation farmer, but unlike many of his neighbors whose grandfathers homesteaded land in the nineteenth century, he has owned land in the county only since the 1960s. He grew up on a small farm in another part of the state, helping his dad raise cattle, and expected to do the same when he finished high school. Money was always tight, but the cattle market was steady, and by working as a day laborer he was able to make his first down payment on a piece of ground of his own. Over the decades he and his wife have lived frugally, worked hard, and gradually expanded their holdings.

He currently farms more than nine thousand acres or about six times as much as the average farmer in his community. That acreage includes land he owns or rents, and is spread across two counties and spans an eighty-mile radius. His largest field encompasses two-square miles or more than twelve hundred acres. At age seventy, he shares the farming with his son, but still does much of the tractor work himself. With a 550-horsepower tractor that costs more than $150,000 and pulls a sixty-foot cultivator, he can till forty acres an hour on a good day. “I’m old enough to retire,” he says, “but that word isn’t in my vocabulary. I’m just going to keep going as long as I can.”

The Janssens are by no means the richest family in town. Several other farmers own more land than they do. But big farmers are clearly the local elite. The Janssens live in a new section at the edge of town. Their house is worth twice as much as the average home. Their annual income puts them in the top 1 to 1.5 percent in the community. From year to year their cash flow varies, depending on rainfall and grain prices. But crop insurance and government subsidies even out those fluctuations, and over the decades land values have steadily risen.

The Janssens’ lifestyle is an indication of their position in the upper stratum of the community. They are regulars at the Presbyterian Church, the most upscale congregation in town, and have enough money to travel. Like others of the town’s elite, the Janssens are expected to take leadership roles in the community and do so largely through their volunteer activities. Mr. Janssen has served for years on the church board and belongs to the Elks club, which until a few years ago operated the town’s finest dining facility. His wife volunteers at the hospital, and he chairs a community-wide committee for the Lions club.

The landed gentry are often wealthy enough to own a vacation home in another state or private airplane. It is hard for them not to stand out in a small community. They usually live in a house that is newer or larger than average, have enough money to pay for hired help, and are able to spend weekends away going to ball games or shopping. How they are viewed in the community depends on how they attained their wealth and what they have done to care for their land. “Oh yes, those are the farmer gods, the rancher gods,” a shopkeeper in a town surrounded by large farms and ranches observes, registering the ambivalence that people of lesser means frequently feel toward the wealthy.

In Mr. Janssen’s case, he sometimes feels like a newcomer, compared with neighbors whose grandfathers came as pioneers, but the fact that he was once poor and has accumulated land by working hard is a source of respect in the community. The landed gentry who are definitely not respected are the ones who are known to have attained wealth and purchased land because of having squeezed out poor farmers during the Great Depression, or because of oil or natural gas being found on their property. The ones who are respected are usually people like Mr. Janssen who are seen working in the fields themselves and serving on civic boards in their communities.

Although physical labor comes with the territory, daily life for the landed gentry is currently dominated by office work and managerial tasks. “I spend an awful lot of time behind the computer,” a rancher who manages a large spread of irrigated cropland in another high plains community remarks. His day begins with checking the overseas financial markets, and determining whether or not to sell some of his grain. With forty to fifty thousand bushels on hand, fluctuations of ten or twenty cents make a significant difference. Other days he studies online crop reports, learns about new varieties of genetically modified seed, and makes decisions about farm loans and new equipment. Lately, for example, he has been figuring the relative costs of purchasing new engines for his irrigation wells to take advantage of alternative fuels. He still spends long days in the fields during planting season and harvest, but says his work is increasingly done indoors.

For people who live in cities and know little about farming except what they read in urban newspapers, it is important to understand that many of the people who live in or near small towns and farm are not truly part of the landed gentry. This is because someone else owns most of the land they farm, and much of the machinery they use is heavily mortgaged to the bank. An instance would be a couple in their early forties we met in a town of about thirteen thousand. They farmed fifteen hundred acres, which was well above average for the county in which they lived. But they owned only eighty acres. The woman’s mother along with several aunts and uncles who had retired, or who had inherited land from the previous generation and kept it because it had been in the family, owned the rest of the land. This couple might eventually join the landed gentry if they do well and inherit the land they now rent. Yet they are currently heavily in debt because of the machinery they had to purchase and expect that will continue to be their financial situation. By the time the loans on the machinery are repaid, the machinery is worn out and needs to be replaced with even more expensive equipment. At present, they feel more like wageworkers than gentry. The woman has taught school and worked for an insurance company in lean years to make ends meet.

In most towns, fewer of the elite are involved in agriculture nowadays than have attained status in other ways. Over the decades, one of the surest ways of attaining elite status in small towns, apart from farming and ranching, has been serving as the community’s doctor or lawyer. The stereotypical country doctor or lawyer was a well-educated person who had probably grown up somewhere else, lived in a city while attending medical or law school, cultivated a taste for the arts and literature, and then moved to a small town because of its simple amenities and opportunities for community leadership.8 In recent decades, small rural communities with declining populations have struggled to attract as well as retain doctors (lawyers have not been as scarce) who otherwise would choose to practice in cities and suburbs where hospitals were better and the opportunities for specialization were greater. Towns of five to twenty-five thousand residents have nevertheless been able to secure enough revenue from government programs and through patients’ health insurance plans to maintain decent clinics and small hospitals. For doctors at these clinics and hospitals, opportunities to be among the local gentry have continued. Merely the fact of having an advanced professional degree places them in the upper echelon of their community.9

Dr. Richard Schnell lives in a spacious brick house on a corner lot three miles from the center of this Sunbelt town of twelve thousand. The neighborhood is one of the town’s newer and most expensive subdivisions. If his home were on the market, it would sell for approximately four times the median price here and would be among the top fifty in terms of value. Last year when he retired, his income was in the top 1.5 percent among families in the community, and he earned enough from selling his practice that he and his wife are living comfortably from the interest on their investments.

Life has never been better for Dr. Schnell. As a boy, he lived in utter poverty, helping his dad—who worked as a coal miner—farm a few acres of cotton and peanuts with a team of mules. Most of his high school classmates followed their fathers into the coal mines, he recalls, but he decided early to lead a different life if he possibly could. He joined the army, spent four years in the military, saved enough money to attend junior college, landed a job teaching school, got married, and then with his wife’s help worked his way through college and medical school. His decision to locate in a small town was dictated by an opening that simply became available at the right time. Over the decades the town’s population grew by a third, and his practice expanded.

Dr. Schnell could have devoted his working hours to his patients, and then spent the rest of the time on the golf course or taking vacations. But in a small town it proved impossible to escape becoming involved in the community. He remembers an evening more than two decades ago when some friends invited him and his wife to their house for a Christmas party. These friends lived in the same neighborhood, and knew each other from church and civic clubs. One was a banker; another held investments in oil and gas. The conversation turned to politics. “We were looking for somebody to run for city commission,” he says. “We went to George and asked him to run.” George did run and won.

That would have been the end of the story. But Dr. Schnell’s wife, Elizabeth, picks up the narrative and finishes it. She explains that because of their friend George, her husband was also drawn into community service. Too modest to mention it himself, he served for twenty-two years on the city commission, including a term as mayor, and received a citizen of the year award.

Besides the opportunities afforded for doctors themselves, the health and related social services industry has become prominent enough in many of America’s smaller towns to provide well-paying jobs for the executives who own or manage clinics, hospitals, rehabilitation centers, and assisted living programs. In towns of fewer than ten thousand residents, these health-related businesses sometimes have staffs of a hundred, while in larger towns the number of employees is often considerably more. Other residents can easily regard a top executive of one of these large, prominent local businesses as a member of the gentry.

Joseph Grimshaw is an example of a small-town resident who has achieved a position among the gentry by virtue of success in leading a health-related business. Mr. Grimshaw lives in a town of just under twenty thousand people that has grown in recent years as a regional hub for natural gas production, trucking, and agribusiness. He grew up here, the son of a car dealer who made a decent living but was by no means rich. After high school, Mr. Grimshaw joined the army, gained the maturity and direction he figured he lacked, got married, and went to college in his hometown, majoring in business. He planned to relocate to a large city where jobs were said to be plentiful, but a family acquaintance asked him to apply for a managerial position at the local hospital. He did, and within a few years was the CEO of a rapidly expanding regional medical facility with three hundred employees.

With skill and some luck, Mr. Grimshaw turned his investments into a sizable enough portfolio to step down from his CEO position before his fiftieth birthday. Now in his late fifties, he runs a private investment banking firm in the mornings, and spends his afternoons overseeing the thousand acres of farmland he owns, playing golf, and doing volunteer work. He has been president of the Kiwanis club and active in the chamber of commerce. Currently he divides his time among the local historical society, activities at the Catholic Church, and serving as an appointed member of a state health commission. He says the dream he is most pleased about is being “totally financially independent.” Like Mr. Janssen and Dr. Schnell, his hard work, bootstrap upward mobility, and leadership in voluntary service activities make him a respected member of the local gentry.

How the gentry are changing even in small, traditional rural communities is nicely illustrated by another successful businessperson, Raymond Breyer, a commodities broker who lives with his wife in a rural town of just over twenty thousand. His community has also grown in recent years as a result of light manufacturing and a fledgling alternative energy facility. Until recently, it would have been unheard of for anyone to earn a handsome living in a small town as a commodities broker, but the Internet, changes in banking regulations, and greater interest in commodities trading and the derivatives market among residents of small towns have made this occupation a possibility. Mr. Breyer enjoys the good life by virtue of two things. First, he inherited modest wealth, and second, he cultivated networks well beyond the town that have allowed him to earn considerable wealth without having to leave. As a teenager he worked in the family business, and after college thought seriously about going to law school, but always knew he wanted to stay in his hometown, so decided to return and build up the business.

By the time he was forty, Mr. Breyer was supplying fuel and other petroleum products to most of the county. That was good because the population was growing and fuel prices were high. It also put him in contact with a large number of people locally and throughout the region. “Go out and meet as many people as you can” was his motto. One of the people he met told him about a franchise through which he could become a commodities broker. With electronic communication and satellite connections, businesspeople even in small towns were purchasing hedge funds and trading commodities futures. He added that to his repertoire, and was soon doing well for himself and his family.

The Breyers live in a new golf course community where houses come with three-car garages and cost three times as much as homes in average neighborhoods. “This is the place to live,” he says, pointing out the window to the green grass and trees surrounding the golf course. The Breyers do not particularly like the harsh weather where they live, so they travel a lot, often to foreign countries with cooler climates in the summer and warm sunshine in the winter. They are firmly anchored in the community, but it is as much a place to get away from as to be.

The gentry are usually not called that, of course. Townspeople refer to them as rich farmers, big landowners, the elite, the moneyed people, sometimes pejoratively as the snobs, and frequently as the country-club set. Country clubs became popular in small towns during the 1950s, having spread widely in larger communities earlier in the century, and soon were one of the clearest status markers in small communities.10 There was usually a golf course along with an exclusive restaurant and sometimes tennis courts. Membership and annual fees were high enough that all but the wealthy few were excluded. In racially and ethnically mixed communities, membership was also reserved for the white majority. The exclusive restaurant provided better food and a more attractive ambience than any other eating spot in town. It generally served drinks as well, and frequently was the only place in town that, as a private club, was able to escape restrictive or prohibitive liquor laws pertaining to public establishments. Knowing how to play golf was a sign of refinement; it was also a form of conspicuous consumption that implied having enough free time to have learned it, and enough money to have paid for lessons and purchased equipment. “Oh, what sold us” on coming here, says a doctor’s wife in a town of thirteen hundred, “was the golf course. We live on the back of number nine green. It’s a real treasure.”

For many of the people we talked to, it was taken for granted that playing golf as a member of the country club or living in a neighborhood with a private golf course was a mark of status. In one community, though, the extent to which this was the case became even more apparent when the town decided that if it was to compete successfully with other towns, it needed to expand the nine-hole golf course to an eighteen-hole one. The cost of membership in the country club was already quite high, so members decided they could not afford to expand the facility. The town council and chamber of commerce stepped in, proposing to underwrite the expansion in return for opening the course to the public and renaming it. As soon as the name was changed from Country Club to Mountain Lakes, business on the course doubled. Yet that was a mixed blessing. It kept fees low, but it increased waiting times on weekends. Mostly what people noticed was that the clientele changed. Rather than the few wealthy residents mingling only with their own kind, a broader set of the population was now present. The gentry wished for the old days when just their friends belonged and a person seldom had to wait to tee off. If nothing else, the controversy showed how important the country club had been in separating the gentry from the rest of the community.

THE SERVICE CLASS

Below the gentry is the service class, which consists of salaried workers who generally have at least some college education, plus business owners and farm operators who are not salaried, but whose educational backgrounds and incomes are sufficient to give them a similar lifestyle in terms of housing, vacations, leisure time, and expectations about children’s educations. Examples of occupations that fall into this category include accountants, bank managers, teachers, registered nurses, and government officials. The largest number of people, who comprise approximately 20 percent of the civilian labor force in small nonurban towns, are employed as teachers, school administrators, and the various health professions. Another 15 percent of the civilian labor force in small towns is employed in public administration, financial administration, insurance, and miscellaneous services.11 Unlike the gentry who have large landholdings or other investments that solidify their ties to a particular place, the service class includes people who could have and perhaps did live elsewhere, but have chosen to live in their particular town. Being there by choice, they value family origins that may link them to the town, an affinity for the region, or job opportunities and ambience. Although they are not as wealthy as the gentry, they are usually well respected in the community, involved in its civic activities and social life, and regard themselves as the providers of valuable local services. Being of service to the community is especially important, both to their own sense of self-worth and how they are viewed by fellow residents.

An example is Greg Parsons, a congenial man who grew up on a small farm in corn country where dairy cows and hogs were the farmers’ mainstay. In the 1970s, he married a farm girl in the community and began renting some land from her dad. With borrowed money, Mr. and Mrs. Parsons invested in hogs and were earning a decent living until the year disease wiped out most of their animals. The Parsons were struggling. “We sat down,” he recalls, “and decided that if we could sell and liquidate what we had, we could pay off our debt.” That plan was successful, and with help from his family and wife’s job, Mr. Parsons earned enough credits at a local community college to receive an associate degree in accounting. As he was nearing graduation, the instructor mentioned hearing about a job opening at a bank in a small town about an hour away. Mr. Parsons applied and got the job. The town covered less than a half-square mile and had fewer than seven hundred residents, but that was OK with Mr. and Mrs. Parsons. It was similar to the farming community in which they had been raised, was less than two hours’ drive from their parents and siblings, and Mr. Parsons could make use of his farm background in dealing with the bank’s farm loans. He eventually became a vice president at the bank, and Mrs. Parsons got a job as a teacher in a neighboring community’s elementary school. Both are proud that their jobs are of service to the community and give them ample opportunities to know their neighbors. The Parsons are happy to have raised their children here. One of their children still lives about an hour away. He and his dad have a few acres outside town. Mr. Parsons calls it hobby farming. He has fixed up an old tractor like the one his dad used decades ago. It keeps him in touch with his roots.

Besides schools and banks, the most common businesses in small towns are often the ones that are connected to the health industry. They are seldom as large as the regional health system Mr. Grimshaw headed as a CEO. Usually they serve a smaller area and operate with a staff of no more than five to ten employees. These small businesses include doctors’ offices, noncritical care hospitals, nursing homes, rehabilitation centers, assisted living facilities, and medical clinics. Health workers, such as registered nurses and office managers, thus make up an important segment of the service class in small towns.

As a case in point, it was during his junior year in college that Alex Keller, now in his early forties, came to the realization that he would soon have to earn his own way in the world. Up to that point he had been content to work at odd jobs during the summer, take required courses, study a little, make passing grades, drink beer with his buddies, and play golf or softball on weekends. He knew it was unlikely that he would ever return to the remote town of twelve hundred where he had grown up. He rather liked the town of fifty thousand where he went to college. In fact, he enjoyed going to the large city nearby and fully anticipated that he would live in one when he graduated. But somehow he also wanted to keep open the option of living in a small town where people knew one another. An anonymous suburb was where he knew he did not want to live. Thinking health administration was one career that might have openings both in cities and small towns, he enrolled in a course on health policy.

Two decades and two master’s degrees later, Mr. Keller is the director of a small family practice medical clinic in a county seat town of five thousand that prides itself on having a stable population and new municipal swimming pool. He and his wife along with their daughter live in a comfortable house in a newer section of town. His job is challenging. Most days there is some crisis on the horizon demanding his attention. Much of the health industry in his state, like in all states, is regulated by a state board, which in turn governs according to legislative mandates. These regulations pertain to everything from safety standards to billing. Then there are constant issues with the insurance companies that want to sock patients with as hefty premiums as the law allows, he says, and find ways to pay as little and as late as they can get away with. It falls on him to keep the clinic’s doctors and nursing staff happy as well as recruit new personnel when someone leaves. He is also the clinic’s main liaison with the community. That means keeping abreast of major community events, organizing public health fairs, handling public relations with the local newspaper, and dealing with disgruntled patients.

From someone in Mr. Keller’s position, a small town can seem like Peyton Place at times. The sordid loosely guarded secrets and other sources of controversy in his town include a doctor whose license was suspended because of a sexual harassment complaint, a woman who rescinded a sexual harassment complaint after it was determined that the complaint was likely to be proven bogus, a newspaper editor who hobnobbed with a doctor at Alcoholics Anonymous meetings and learned things that should not have been disclosed, news that should have been published that was not, and nasty rivalries among doctors and between clinics. For Mr. Keller, it is all in a day’s work to deal with these issues. In fact, he felt that his service to the community consisted of not only doing his job well at the clinic but also smoothing over local conflicts.

Despite all the unpleasantness, life in a small town can be quite accommodating to someone in a management position like Mr. Keller. He could lose his job if some scandal turned on him. But he is good with people, enjoys the local give-and-take, and knows how to keep his head down when necessary. He says he might consider running for the county commission someday because it seldom deals with anything controversial. He would not run for the school board because it is always embroiled in controversy. He knows his views would be liberal enough to get him into hot water with conservatives. If he wants to let his hair down, eat a nice steak, and drink a few more beers than he should, he goes to another town to do it. Meanwhile, he figures a nine- or ten-hour day at the clinic is not a bad way to earn a good living. Housing is cheap. He has a five-minute commute. He still has plenty of time for golf and softball.

The service class in small towns is increasingly supported through government programs, subsidies, and transfer payments. This is certainly true for health workers, who depend heavily on patients who receive government-subsidized retirement and welfare benefits. Transfer payments that contribute to the life of small towns include everything from farm subsidies to Social Security and Medicare to park services and pollution management. County seat towns have been the main beneficiaries of these programs. County offices typically include a register of deeds, a county clerk, and often a county supervisor or manager as well as an elected council. Many counties include an economic development specialist and most include a county superintendent of schools. In farming districts, counties usually include a county extension agent who works with farmers on soil conservation programs and supervises federal farm-subsidy payments.12 These agents are an important part of the service class.

Megan Clarke is the county extension agent in a rural county of eight thousand people, and nearly as many cows and pigs. Agriculture is as key as it ever was, but the work of an extension agent now includes advising nonfarm residents about lawns, gardens, bushes, shrubs, and potted plants, and providing information about nutrition, organic foods, pollution, and pesticides. Ms. Clarke lives in the county seat, a town of thirty-three hundred. She earned an undergraduate degree from the state’s agricultural college, majoring in agricultural education, and a master’s degree in agronomy. She taught high school biology and general science for two years, and now, at age thirty, has been at the extension job for five years. She is the main conduit through which the latest developments in scientific agriculture flow to and from the local community. She handles everything from financial questions about lease agreements to technical questions about planting dates, pesticides, fertilizers, seed varieties, and expected crop yields.

Ms. Clarke says a typical day begins with opening the mail, checking email, and reading the local newspaper in print or online to get a quick overview of any developments in the community she should know about. Those might range from weather forecasts to reports of storm damage to announcements of a farm sale or civic event. Much of her day is then spent answering questions from walk-ins or by telephone, and making two or three site visits to farms where her expertise about weed control, erosion, crops, or livestock is needed. She conducts her own research as well, usually in the late afternoons. Lately she has been working on a potassium deficiency problem in no-till soybeans comparing results in three test plots. Because of the wide range of scientific issues that come up, she consults frequently by email and in person with experts at the agricultural college as well as test stations around the state.

Besides providing her technical expertise, Ms. Clarke also plays a crucial public relations role in the community. Much of the work of planning the annual county fair falls on her shoulders. She has one or two evening meetings a week, which range from speaking at a 4-H club event to appearing at a county commissioners hearing to hosting a demonstration about homegrown food. Although her primary constituents are farmers, she works closely with many townspeople in her area. Many residents have gardens or want advice about their lawns and shrubs, some have children in the 4-H, and all—she hopes—are interested in healthy food.

“I really get a big boost from working with homeowners and farmers,” she comments. “I like to be able to take a situation where they are kind of at their wits end and don’t know what to do next, and help them reason it through using the research-based information that’s available.” She says many times there are no easy or straightforward solutions. But usually some next steps that can be implemented come out of the conversations. “If I have shared with them something that they hadn’t thought about before and are willing to try, even if it doesn’t always work the first time around, then that makes me feel like I’m having a success in my community.”

Those within the service class vary in the degree to which they can be said to have chosen to live where they do. On the one hand, a person like Mr. Parsons was not making it in farming and wound up in a small town partly because he preferred that size community, but mainly because the job was available and housing was affordable. Ms. Clarke, in contrast, could have majored in anything in college and likely have opted for a career best pursued in a city. But she is an example of someone whose love for the land was so strong that it guided her into a career in which she could do a lot of what farming involves without actually having to farm. She grew up on a cattle ranch twenty miles from the nearest town. She loved living in the country and following her dad around as he worked with the livestock. Her parents were college educated, and she expected to go to college as well. In high school, however, she planned to study in college to become a teacher. She dreamed of marrying a farmer and living on a farm. She knew she did not have the capital to become a farmer herself. So being a farmer’s wife and having teacher training that she could use in any rural community was her goal. She even bet one of her high school teachers that she would be living on a farm in a few years. As her thinking matured, she realized she could combine her interests in teaching and agriculture, and in so doing, would be more in command of her own destiny rather than needing to marry Mr. Right. When she did find Mr. Right, he was not a farmer or even from a farm background. Yet her plan to do something in agriculture has been realized. “Ultimately, things aren’t that much different from what I expected,” she notes.

The service class also typically includes some of the established business owners who operate stores on Main Street that have been there for years. Other than the bankers, though, these merchants in many of the smaller towns have seen their ranks seriously diminished in recent decades. For food, clothing, furniture, appliances, and most durable consumer goods, townspeople are willing to travel thirty or fifty miles to a larger area where shopping is more abundant and prices are lower. That leaves Main Street to the businesses that can stay afloat through consumer loyalty and the attraction of being local, and thus more convenient. At the high end, a few insurance agents, realtors, accountants and appraisers, pharmacists, and attorneys can find a local clientele. At the lower end, Main Street is most likely to include a hairdresser, coffee shop, and tavern, and be supplemented on the outskirts by fast-food franchises, pizza parlors, gas stations, and automobile repair shops.

Some of the farmers we met could reasonably be considered part of the service class as well. This was especially true of younger farmers with specialized college degrees in agriculture, agronomy, social science, economics, or business who rented enough land to have state-of-the-art equipment on loan from the bank, or who operated feedlots or poultry farms. They were among the few with farm backgrounds whose fathers or uncles had done well enough to pass a farm along to the next generation. Although their income depended on crops and livestock rather than a regular salary, they could almost be thought of as service professionals engaged in tending land, caring for animals, and producing food. Like many others in the service class, government programs, including government-subsidized crop insurance as well as government-mandated soil conservation and food safety standards, heavily influenced these farmers’ work. The young farmers hedged against fluctuations in grain and livestock markets by trading in commodities futures. They timed the sale of commodities to produce a regular income. A typical day focused on monitoring carefully blended feed mixtures, inspecting sick cattle or hogs, checking soil samples for fertilizer and pesticide levels, reading the latest science reports and business forecasts, and supervising low-skilled workers who performed most of the manual tasks. One farmer we talked to had a global positioning system that guided his tractor through the field and automatically adjusted cultivation depths while he made business calls on his cell phone from the air-conditioned cab and did computer work on his laptop.

WAGEWORKERS

Small towns seldom have the large manufacturing plants found in most cities, but it is rare to find a small community devoid of workers employed at low to moderate hourly wages. Except in the smallest towns, it is possible to find small firms that manufacture such items as pallets, mops, brooms, wiring for computers, aircraft navigation components, or recreational vehicles. Other examples among the towns we studied include bank supply companies that print checks, telemarketing companies, insurance-claims-processing firms, biodiesel facilities, and metal-fabricating plants for steel and aluminum roofs. In towns of fifteen hundred to three thousand residents, a typical plant of this kind might employ between twenty-five and a hundred workers. In addition, wageworkers include residents employed in meat-processing plants, oil refineries, mines, and pipeline stations, at feedlots or on truck farms, in construction, and working as waitresses, cooks, school bus drivers, and janitors. On average, approximately 15 percent of the civilian labor force in small nonurban towns of twenty-five thousand people or less work in manufacturing, 8 percent work in construction, and 6 percent are employed in transportation occupations such as trucking and delivery services. Wageworkers in small towns also include many of the clerks and office assistants who work in retail stores and administrative agencies.13

Mr. Yeager and his wife, Brenda, live with their three children in a town of about twelve thousand people that became the location of a small oil refinery in the 1930s, and more recently has attracted several manufacturing firms because of its cheap labor supply and proximity to an interstate highway. The Yeagers’ home is a comfortable three-bedroom, two-car garage house in a quiet section of town that was added in the early 1970s. It is heavily mortgaged, but if they were to sell it, the price would be slightly above the median value of housing in the community. He is a crew chief at a factory that manufactures machinery and light equipment. She has worked until recently as a dental assistant. After high school, Mr. Yeager took classes at a technical school, where he specialized in automobile collision repair. He did body repair and painting for eight years before switching to his present job, which he has held for nine years. He commutes twenty-five miles each way to work. Mrs. Yeager was commuting thirty, but has recently quit because gas, automobile maintenance, and child care are costing more than she was earning.

The Yeagers are typical of small-town wageworkers in some respects and atypical in others. The factory where he works is one of the few left in their area and was purchased a few years ago by a company in Finland that also has plants in Brazil. It is a nonunion plant and wages are low, but several new product lines in recent years have resulted in steady employment. Mr. Yeager gets up at 3:30 or 4:00 every morning, starts his shift at 5:00 a.m., and works until 3:30 p.m. It is a good schedule because he can be home during the late afternoon and evening hours when his children are at home too. He feels fortunate because manufacturing jobs in the area are rare. One plant recently closed. He says he could earn more if he worked a swing shift, rotating days and nights, but he considers being with his family more important.

The Yeagers’ commute is increasingly typical of wageworkers in small towns. They live in one community because they like the schools or because it is central to both spouses’ jobs, but they are not well integrated into the town. In the Yeagers’ case, they appreciate being able to send their children to a good Catholic school, but Mr. and Mrs. Yeager are too busy commuting to know many of their neighbors or be involved in community organizations. What they like best about their town is that it is quiet. What they do not like is that housing prices are about 50 percent higher than in some of the smaller towns nearby. In these ways, the Yeagers differ from small-town residents who live there because they have close friends and enjoy being well integrated into the community. They are also atypical in having relatively well-paying jobs. He says he wishes he had gone to college, but was not able to afford it and figures it would not have helped him improve his finances anyway.

Down the scale a notch and more typical of modest-income wageworkers in small towns is Gail Saunders, a thirty-year-old mother of two whose husband, Don, works in construction. They live in a town of fifteen hundred people that has declined by about a third since 1980. She finished a year of junior college before they got married. Her husband began working full-time right after high school. For several years, they lived in another state where he was able to find employment as a roustabout for an oil-drilling company, and she worked at whatever she could find. That included jobs at casinos, hotels, and restaurants as well as in telemarketing.

For a while the Saunders lived in a town of fifty thousand near a city. Construction was booming, but housing was expensive. During an economic downturn, they found themselves falling behind on bills, and so decided to move back to the small town where Mrs. Saunders had been raised and near where her parents owned a farm. Her husband drives thirty to fifty miles each way to and from construction jobs in the area. She worked briefly as a waitress, then as a clerk in one of the county offices, and most recently as a teacher’s aide at the school.

Mrs. Saunders says that while growing up, she always imagined she would live in a city. She never thought she would return to her hometown. But it has been nice to be near her parents. Her mother helps with the children. Finances are tight. Mrs. Saunders says a lot of their bills are on payment plans because her husband’s income varies from week to week and month to month. Their biggest expense is the payments on her husband’s truck along with the gas and maintenance it requires for his daily commute. Still, housing is cheap and life is simple. She enjoys the children she works with at the school and has time to help with the annual 4-H club’s fair.

Then there are the wageworkers who have chosen to stay in their hometowns for one reason or another, even though they might be better off financially in a larger place. Unlike the Saunders, they have not tried living in a city, and have not been forced to live in a small town because of job loss or financial difficulties. They are perhaps uncertain about what they want in life, lack ambition, or want to be helpful to their parents.

Sam Ferguson was twenty-seven when we met him at his home in a town of three thousand. The town has a Main Street with an antique store, a pizza parlor, a post office, and a few other stores. At one edge of town is a recently added modern gas station with a convenience store, a repair shop, and the trucking company where Mr. Ferguson works. He drives eighteen-wheelers delivering and picking up goods in thirty different states.

The reason he lives here is that this is where he grew up. His father farms some land in the area, and Mr. Ferguson helps with the farming when he is not on the road. As a boy he imagined himself becoming a fighter pilot, but as an adult he would prefer to farm instead of driving a truck. The reason, he says, is that he would like to be his own boss—which is part of what he likes about being on the road most of the time as well. Maybe someday when his father retires, he will get a chance to farm. Meanwhile he lives here in this small town, and other than the church he was raised in, he belongs to no community organizations and is away too much of the year to feel part of the activities that make up the town. Asked what he likes best about the community, he replies, “It is just my home.”

Although manufacturing is not as common in small towns as it used to be, communities of no more than two thousand residents may have as many as a hundred workers in manufacturing jobs, while larger communities have considerably more.14 Because of that history, residents frequently argue that the future of their town rests on being able to attract a new manufacturing plant of some kind. But the chances of that happening are not good. If it does, it may not spell success either. Chances are, the firm will be a nonunion plant and will hire only a small number of employees. In one of the communities we studied, for example, there had been a cigarette lighter plant for some years. The pay was $6.50 an hour at a time when jobs in construction were paying twice that much. “Do you think we can compete with China?” a community development specialist asked. “Manufacturing is not the answer. It’s not going to be the union manufacturing jobs that our grandparents knew about.” And yet when he was pressed to say what might take the place of these jobs, he was at a loss. Perhaps the community could attract low-income retirees. Or revitalize the dairy business. Those too, however, would provide only a few low-paying jobs.

In other towns, community leaders described a class of people they called the working poor. Not all of the working poor were wageworkers. Some were small farmers and business owners whose incomes had never been high, and were now depressed because of weak crop and livestock markets, lost jobs in mining and manufacturing, and declining populations. The working poor included men and women earning low hourly wages in fast-food businesses, as farm and construction laborers, and doing office assistant work. In many cases, they did not have health insurance or retirement plans. Some were living in homes that were in bad repair or had been condemned. Others were living in aging mobile homes or flood zones.15

PENSIONERS

Pensioners are another identifiable category of residents in small towns. They are usually older and are retired or semiretired, and for this reason exhibit a different lifestyle and have different needs from those who work full-time. In many small towns, older residents make up a larger share of the population than would be true in most cities and suburbs (as shown in figure 2.2).16 There are of course exceptions. In fact, the percentage of residents age sixty-five and older in more than three thousand small nonurban towns—approximately 20 percent of all such communities—is actually the same or lower than in large cities. But with these exceptions, older residents generally constitute a distinct and important group in small towns. They may have lived in their town all their lives, be intensely loyal to it, have children or grandchildren in the area, and expect to stay until they die. The relatively slow pace and inexpensive housing in small towns suit them. In other cases, they may have moved to a smaller community after having lived in a city or suburb in order to experience these benefits. They vary considerably in their standard of living, ranging from those who live comfortably because of retirement savings and investment incomes, to those who exist on meager Social Security checks.

Figure 2.2 Population age sixty-five and older by town size

George Ainsley and his wife, Mary, live in a town of sixty-five hundred that derives most of its income from farming and the petroleum industry. The population is about 10 percent smaller than it was in 1970, but about the same as it was in 1940. Mr. Ainsley is seventy-five, retired, and suffers from Parkinson’s disease. He is the fourth generation of his family to make his home here. One of his uncles still farms in the area.

When Mr. Ainsley was growing up he worked on his uncle’s farm, played basketball, and imagined himself becoming a coach someday. After high school, he took some bookkeeping courses at the local junior college and decided he was good enough at it to think about accounting as a career. He went off to a college, which was in a city about eighty miles away, and majored in accounting. His farmwork in high school helped him land a job in the finance department of a government farm credit office in that city. But Mr. Ainsley’s dream was to live in a smaller town. He earned a license as a certified public accountant and returned to his home community. Eventually the work became too demanding and began to destroy his personal life. He quit doing public accounting, worked for a while at the junior college, and then found an administrative job for a government bureau that had an office in his town.

With Social Security and the savings he put away while he was employed, Mr. Ainsley says he and his wife are able to live pretty comfortably. It helps that his wife owns some land. They live about a mile from the center of town near a golf course. Mr. Ainsley enjoys eating breakfast at McDonald’s, runs a few errands in the mornings downtown, and when the weather cooperates, plays golf in the afternoon. His skills in accounting keep him busy the rest of the time. He keeps the books for one of the community’s volunteer organizations and serves as treasurer at his church.

“We have a pretty unique community,” Mr. Ainsley says. “It’s a division point for the railroad. We have a junior college. We have a great hospital and some good doctors. We have a nice downtown area, and it’s easy to get around, and you know most of the people. We don’t have a lot of crime or traffic.” For him and his wife, the town is just the right size. It has the services they need, including doctors who come out once a week from the city. And as much as Mr. Ainsley likes having people around, it is the fact that there are not more of them that matters just as much. “In the cities,” he remarks, “you have to fight for a tee time at the golf course. Maybe get up at four o’clock in the morning. Here, you jump on the course and play nine holes, and probably do not see anybody.”

Older couples like the Ainsleys live where they do because they know people, do not mind eating at McDonald’s, and enjoy amenities that they could just as well find in a city or suburb, but can participate in less expensively and more easily in a small place. Other pensioners are oriented more toward the land, even though they may live in or near a small town. They may appreciate having friends and family in the community, but it is the chance to do some hobby farming and have a garden or backyard workshop that is most appealing. An example is John and Katherine Bradford, a couple in their late sixties. They live just outside a town of six hundred populated mostly by other retirees. This is Mrs. Bradford’s hometown. She says her family has lived here for seven generations. Mr. Bradford is a newcomer. He has lived here only for forty years. He grew up in a larger community 125 miles away, moving here to take a job as a high school teacher.

The Bradfords are not rich, but they live comfortably. During the summers when he was not teaching, Mr. Bradford built houses and saved enough money to purchase the small farm they live on now. He grew up on a farm, hating every minute of it. The old tractor his father owned never ran well, and his parents made him do chores before school and every evening. He envied schoolmates who lived in town. But after going away to college and working for several years as a teacher, he missed the farm. He would rather have turned full-time to farming instead of teaching, yet there was no way he could afford the land and equipment he would have needed. So he settled for a few acres with a barn where he could raise a few cows and have a garden. Mrs. Bradford had a little store in town. Her dad was a cowboy. Eventually she inherited some land, when her father died. One of their sons farms the land. Between Mr. Bradford’s pension from teaching and some income she receives from the land she inherited, they pay their bills and have enough money to pursue their hobbies.

People like the Bradfords would never leave the small community they call home. Being a teacher in a small town, Mr. Bradford knows everyone. He was also a county commissioner for nearly a decade. Having run a store, Mrs. Bradford knows everyone as well. They mostly enjoy having a barn with a few cows and lots of cats. Mr. Bradford has nearly lost the use of one of his legs. So he has difficulty getting around. Driving is hard and he doesn’t like to travel. Mrs. Bradford does. She drives several hundred miles to visit children and grandchildren. Her hobby is gardening and painting china. She goes to conventions in big cities around the country where hand-painted china is displayed and classes are given. As small as their town is, they feel closely connected to the rest of the world. That sense of connection has increased in recent years. Every evening they read and send emails. They have family and friends all over the world.

Although the Ainsleys and Bradfords lived in their towns before they retired, they are similar to a small but growing number of people who have lived elsewhere, usually in cities or suburbs, and then move to a smaller community to retire because housing is cheaper and life is simpler. A community leader we talked to in a town of only a thousand that was two hours from a metropolitan area said this was increasingly true in his town. “We have a number of retirees who have come from larger communities and are financially comfortable, or at least aren’t hurting for money,” he said. “You can buy a fixer-upper in this town for under twenty thousand dollars, a decent house for fifty thousand, and a really nice house for under a hundred thousand.” Those people sometimes sold their home in the city for three hundred thousand dollars and invested the difference. But there were retired people in that community and many others like it who were struggling. For them, staying in a small town was what made it possible to meet their expenses at all.

Mr. and Mrs. Ted Dallek are an example of an elderly couple that can barely survive on their subsistence income. They live in an unincorporated town that consists only of a paved highway, railroad crossing, and several old buildings that once served as the town’s stores, but long ago were turned into garages and storage sheds for the few people who remain here. Grass grows between the railroad ties because the train no longer comes. A few rusted farm implements lie in the weeds behind one of the storage sheds.

The Dalleks lived in a different state for more than half a century. He served in the Korean War right out of high school and then worked as a farm laborer for several years. After that he purchased a small hardware store, got married, and raised two children. Mrs. Dallek helped in the store, mothered the children, and eventually got a part-time job caring for the elderly at a nursing home. By the early 1970s, competition from chain discount stores had become intense and the Dalleks had lost most of the money they had invested in the hardware store.

Their daughter lived near their present location, so the Dalleks decided to move closer to her. Mr. Dallek took an hourly job at a small sheet-metal-fabricating plant eleven miles away. They put a down payment on the house in this unincorporated town because it was all they could afford and because it had a big backyard. With his income and her work at a retirement home, they were able to pay off the mortgage. He has a woodworking shop, and they enjoy growing apples and pears in their backyard. They have few expenses, do not travel, and still own the small black-and-white television set they purchased decades ago. There is a town of seventeen thousand six miles away that has all the medical services and stores they need. Their daughter looks after them when they need help. At eighty-seven, Mr. Dallek says the past decade has been the best time of his life. He explains that they will be OK until one of them goes to a nursing home. At that point, they will have nothing.

Like the Dalleks, many of the older people who live in small towns are not dependent solely on Social Security or pensions from previous employment. They have children who send them money, or help in small ways with transportation and home repair. Sometimes they continue to work at part-time jobs or operate small businesses well past the normal age of retirement. They hang on to the business as long as their health permits. It supplements their income and gives them something to do.

Dorothy Martin is a seventy-year-old widow who lives in a riverfront town of nine hundred. Her husband died eight years ago. She received Social Security as his survivor and now that she is seventy draws her own Social Security. She grew up in this town, raised by grandparents who owned a farm in the area. After high school she took a short business course and moved away to a large city, where she got an office job working for an insurance company. It was there that she met her husband, who worked in retail sales.

In their early forties, the Martins decided they wanted a slower pace of life where the cost of living was less expensive. They had tried running a lamp store for about a year and were having financial difficulties, but they both enjoyed having a business of their own. Mrs. Martin had never thought about returning to her hometown, but she had a brother there and through him had kept up on news from the community. She learned that a five-and-dime store had closed recently, and the townspeople were hoping someone would come and reopen it. She and her husband decided to try it. The town’s population was declining and other stores went out of business, yet they managed to keep afloat. At seventy, she still has the store. She has tried to sell it, but nobody wants it. It gives her something to do and helps with her bills. She figures as long as her health permits, she will keep running the business.

Pensioners also include the elderly poor who are nearly destitute, such as widows, widowers, or couples who have never owned enough land to break even or a business that earned enough to set aside money for retirement. They have worked for an hourly wage most of their lives and now are faced with medical bills. If they are a couple, and one is younger or healthier than the other, the younger or healthier person may continue to work at odd jobs or part-time. They cannot afford to move because their home, if they own it, is worth little or because they could not afford an assisted living facility in a larger place. They get by on Social Security and Medicaid along with help from their neighbors. If they are fortunate, some of their family still live in the area, and can help with transportation and home repairs. Others are less fortunate. Their savings have dwindled dramatically because of reverses in the economy. Perhaps they expected to work longer, but lost their jobs as they neared retirement, or lost their pensions or health care. If they have lived long enough, they might have depleted their savings.

Mr. Ainsley says there are a lot of people like this in his community of sixty-five hundred, where there have never been many high-paying jobs. People work at a low hourly rate and often have a pretty hard time of it, he says. He mentions an elderly couple he sees when he eats breakfast at McDonald’s. “He’s up in the nineties, and she’s in her late eighties. I know they have a difficult time. They drive an old beat-up car and they’ve rented their house all their lives. They were never able to accumulate much. Somebody said that their kids send them some money every month to where they can go out and eat.”

Another couple we talked to, Myron and Frieda Epworth, live in a town of nine hundred people. He is sixty-nine, and she is sixty-five. They live in a small farmhouse on the edge of town. Their oldest son and his wife live across the road. Mr. Epworth’s father died when Mr. Epworth was seventeen. Mr. Epworth quit school and took over the farming as best he could at that point with help from an uncle who lived nearby. Only fifty acres of the land could be tilled for crops, so the farm income came mostly from hogs and cows. It was never enough to cover the mortgage, and thus Mr. Epworth worked during the week at whatever hourly jobs he could find. He worked as a day laborer at the grain elevator, ran a truck at the quarry, and for many years worked as a janitor at the local nursing home. Mrs. Epworth, whose education also stopped with high school, worked as a nurse’s aide and filled in for a few years as the local social services director before her lack of training disqualified her from retaining the job. She took several different part-time jobs doing office work and as a private-duty nurse’s aide, and for the past decade has been the dispatcher at the sheriff’s office.

By almost any standard, the Epworth’s are among the elderly poor. Mr. Epworth’s income is seven hundred dollars a month from Social Security. He is no longer able to work as a janitor, so spends his time puttering in the yard and is essentially retired. Mrs. Epworth earns eight dollars an hour from her job. She works twelve-hour shifts. She enjoys the work, but finds it increasingly difficult at her age and only keeps at it because they need the money. She drives a car they bought used for two hundred dollars fifteen years ago. He drives a thirty-five-year-old pickup. “If you sit on the passenger side,” she says, “you have to be careful where you put your feet because you might be acting as a brake.”

MARKS OF DISTINCTION

Much of what people say about their towns, as we will see in the next chapter, suggests that people get along well with one another, and indeed, there is plenty of reason to believe that many aspects of small-town life do serve well to strengthen communities. Because neighborliness and community service are such vital elements of town life, we need to pause briefly at this point to note that social distinctions not only exist but also that these distinctions are sources of misgiving. This is especially true of attitudes among middle- and working-class townspeople toward the very rich and very poor. In a hill town of thirty-six hundred where the median household income was only fifteen thousand dollars, for example, a lifelong resident who worked at the bank told us that two local families seemed to own most of the rental properties in the area and had enough money to go on vacation whenever they felt like it. Residents criticized these families, she said, with remarks such as “Their money is just because of their parents” and “They think they’re big stuff.” A county supervisor in a small rural town on the West Coast summarized a similarly negative attitude toward rich families in her community by describing them as people with “toys”—“nice toys, airplanes, boats, race cars, summer homes.” We heard complaints in small towns with declining populations that it was the landed gentry who were responsible for the community’s downfall. “All we have left here are the rich,” a man in a town of little over a hundred griped, referring to “massive landowners.” He said “they won’t tell you they are rich” but they are. In another small community, a long-time resident complained that “the have’s pretty much do what they want, whether it is for the good or not.”

Not surprisingly, the gentry in small towns are sensitive to these criticisms, and sometimes try to hide their wealth by living below their means or at least refraining from ostentatious conspicuous consumption. Mr. Janssen, for example, drives a weathered pickup truck instead of purchasing a new one. The Janssens could easily afford a more luxurious home. A large landowner in another community says, “A BMW out here sticks out like a sore thumb. If somebody is driving a Cadillac, well, Jimminy Christmas, they’ve got their nose in the air! I drive a Chevrolet.” The doctor’s wife I mentioned who lives near the ninth green of the local golf course says they never owned a boat or purchased anything very expensive, but she knows there have been criticisms. “If we got something new, it might be because [my husband] had to admit a patient and charge. That’s where we got our money. But he never overcharged. Those stories aren’t true.”

Generational misgivings are evident, too. Usually the elderly are objects of veneration, as demonstrated in comments about how self-sufficient they are and how they may have endured hardship as children of early settlers. Less favorable sentiments emerge, though, in remarks like this one from a thirty-year-old: “Seventy percent of the people in our town are elderly. They like it here. They can be eighty years old and unable to see, but they still drive their cars. The rest of us have to swerve out of their way.” There are equally negative comments from elderly people about the younger generation. Typical complaints focus on young people not having good morals as well as being too busy or materialistic to help with community projects. The reason the community is not prospering, elderly residents sometimes say, is that younger people are no longer willing to work hard. “They just want everything to fall into their lap.”

As between the service class and wageworkers, the distinction rests principally with having or not having been to college. Longtime residents suggest that this distinction is growing wider. “I had a lot of friends who chose not to go to college when they got out of high school,” a man in his sixties says. “They went to work in manufacturing or something like that. They have done OK.” But now, he explains, things are different. “That person is going to be lucky if he works for a nine or ten dollar an hour job. And ten years from now, he’ll be getting only twelve or thirteen dollars an hour. He has nothing to look forward to.” In contrast, someone with a college education has a more promising future. “There’s a pretty big divide there,” the man notes. “If you have a college degree, you can at least try to impress people with that fact.” In short, there is a perceived difference in current income, but even more so in one’s prospects for the future. A service worker can look ahead, expecting to move up and earn more, send their children to college, move if it becomes necessary, and count on a decent retirement plan. A wageworker may be fine in the short run, yet has a limited horizon that not only restricts future earnings but can also focus one’s attention too much on the struggles of the moment. As one resident observed, “It’s a tough lot.”

Wellsville, New York, is a village of forty-six hundred nestled in a valley along the Genesee River eighty-five miles southeast of Buffalo. A visitor here would observe aging storefronts near the town center, some of them now vacant, and quiet tree-lined streets, vivid with color in the fall. An observer would also witness the inevitable diversity that exists in towns like these, most noticeably in differences between the modest frame houses along Broad Street that cost less than fifty thousand dollars and the newer brick ones at the northern edge of town and across the river to the south that cost three times that much.