Introduction

IMAGINE LIVING IN A COMMUNITY WITH NO TRAIN, no light-rail service, no buses, and in fact no public transportation of any kind. Not even a taxi. The nearest airport is two hundred miles away. Imagine living in a town with only one small grocery store where prices are high and fresh produce is seldom fresh. The selection of items there is small. The best local alternative to home cooking is a high-calorie meal at a fast-food franchise. A nice sit-down restaurant is forty miles away. That is also the distance to the nearest Walmart and shopping mall. If you are a woman with a college degree, your best options for employment are the public school, the bank, a government office, or the nursing home. Whether you are a woman or man, your salary is 30 to 40 percent lower than if you lived in a city. Your children are likely to do reasonably well in high school, play sports, perhaps graduate with honors, and go to college, but they will not have had advanced placement classes and will find adjusting to a large state college campus as confusing as it may be exhilarating. They are unlikely ever to return as permanent residents of your community. As you grow older, they will come to visit you once or twice a year. You are happy to have a doctor and the nursing home nearby. The doctor is a general practitioner. The nearest specialists are an hour’s drive. If you suffer a heart attack and call 911, the county dispatcher will phone a volunteer, who will then drive to the fire station where the emergency vehicle is parked. If you survive, a helicopter will fly in and take you to a hospital a hundred miles away.

Put this way, it is hard to imagine why anyone would want to live in a small town. Yet at least thirty million Americans do reside in these small, out-of-the-way places. Many of them could have chosen to live elsewhere. They could have joined the vast majority of Americans who live in cities and suburbs. They could perhaps be closer to better-paying jobs, convenient shopping, a wider range of educational opportunities, and specialized health care. Rich or poor, they would then be within minutes of shopping malls, restaurants, and hospitals. They could decide to live as anonymously as they might want to, pick and choose among a wide variety of friends, and enjoy mingling with people of vastly diverse backgrounds. There would be chances to explore specialized employment, entertainment, and leisure interests. But they have opted to live differently.

Why? Is it only because of where they were raised? Did they originate in small places and simply find themselves left behind as others moved on? Are their options limited because of family obligations? By the kind of work they do? Are they stuck in rural America because they lack education? Or have they made a considered decision to reject what they regard as distasteful about cities and suburbs? Have they found local amenities that make up for the lack of better jobs as well as more convenient access to goods and services?

The standard answer to these questions is that people live in small towns because they value community and cherish the support it provides. They might well have chosen to live elsewhere—indeed, many of them have—but they prefer living in a small town because the community gives them a sense of belonging. They know everyone. They see their neighbors at backyard barbeques, school functions, and church. The community is familiar, and a place they know and cherish as their home. Its inhabitants share similar values and lifestyles—ones that probably were more common in the past than they are today.1

But these easy assertions about community need to be interrogated. Most of what is known about community in small towns is from brief journalistic accounts that focus on newsworthy events, such as a mining accident or shooting spree, or that provide quotes from the hinterland as background coverage of a political campaign. Or it comes from polls in which questions about small-town life are posed in broad terms that give only a general impression of how Americans feel about their places of residence.2 Hardly anyone bothers to find out how townspeople actually think and talk about community.

Nearly a century ago, sociologist H. Paul Douglass wrote that small towns—of which there were about twelve thousand scattered across the United States—were popularly regarded as “a sort of unsexed creature” that carried neither the romance of the countryside nor intrigue of the city. This was the sentiment expressed in the saying that God made the country, humans made the city, but small towns were made by the Devil. That view was mistaken, Douglass contended. The hope of America, he believed, lay in the strength of its small towns.3

The questions animating Douglass’s interest in small towns were quite different than the ones that arouse my interest now. He was especially intrigued by the tensions between townspeople and farmers, and the differences between Americans who strolled on sidewalks and those who walked on dirt. It struck him, however, that there was something perennially distinctive about these small communities. It mattered that they were incorporated, and were places in which people worked and lived, not apart from one another as they did in the countryside, but together on a small scale. It was the togetherness that mattered. “There’s a town under every town,” he wrote. To find it was the difficult task.4

In the recent social science literature, a great deal of attention has been devoted to the role that social capital plays in communities. There is no question that social capital is important. People who are connected with one another, the research suggests, tend more often to work on community projects, serve as volunteers in their community, vote, pay attention to political issues, and for that matter feel better about themselves. Networking has come to be of increasing interest as data are collected in surveys about friendship patterns and memberships in organizations, and as email and online social networking sites have increased in popularity. Still, social capital and networking are by no means all that matters in understanding community.5

Small towns can only be understood by paying attention to the cultural constructions that give them meaning. They exist as ideas or concepts that provide the people who live in them an identity and way of talking about themselves. Only by understanding this cultural aspect of community can we make sense of the deep role that it plays in the lives of small-town residents. Their sense of community is reinforced by social interaction, but is less dependent on social networks than we might imagine. Community is maintained as an identity by symbols and rituals such as town festivals that actually do not take up much of residents’ time. Social network studies would suggest that community is important because people spend a lot of time making friends and visiting with one another. But social network theory does not explain why people behave as if they know one another even when they do not or why a brief exchange at the post office can communicate more about community than a long conversation might in some other setting.

To be sure, friends and neighbors are crucial to people who live in small towns. But so is the fact that they live in a community. The town has an identity as a community. Its meanings are inscribed in particular places and the tangible aspects of these places—the park, school building, and stores on Main Street. The town’s identity is reinforced in festivals and ball games, small acts of kindness, recovering from a disaster, and the stories that are repeated about these events, and by the local cultural leaders who keep the stories alive. Towns are defined as well by that which they are not—cities, unfamiliar places, and big government. The stories and symbolic markers of difference define a place as a community.

Questions about the real or imagined decline of communities also need to be addressed by examining the ways in which community is culturally constructed. Too often the decline of community has been studied by looking at particular questions in surveys because those data happened to be available. Data on memberships in voluntary associations, voting, and spending evenings with neighbors are examples. It is interesting, though, that in talking with hundreds of people, many of whom did in fact think their community was declining or that communities like theirs were disappearing, not a single person mentioned these standard indicators. Membership in voluntary associations, voting, and spending evenings with neighbors simply did not come up. What did matter were the changes that served as public symbols of community. Decline is symbolized by the hardware store on Main Street that now stands empty or vacant lot where the drugstore used to be. Decline is evident in the fact that the school has closed, or if it remains open, is now a consolidated district that goes by a numbered designation and includes children from someplace else. If anything about social networking comes up at all, it is not that volunteer organizations and dinner parties are lacking but rather that there is no longer a crowd on the street on Saturday evenings.

When residents of small towns describe their communities, a rich tapestry of meanings, narratives, family histories, and personal experiences emerges. People tell of moving to a small community to raise their children without the hassles of city life. They confess to having lost their job in a larger place and seeking refuge where housing was cheap. For some, the hope of taking over the family farm when a father or uncle retired kept them tethered to a small rural community. For others, it was a decision to marry—perhaps fraught with ambivalence about giving up an ambitious career—or live near an ailing relative.

Viewed from the inside, community ceases to be a bland abstraction. Townspeople do talk about knowing everyone, but we learn what that means, who is excluded, and how that is reinforced in the small details of sidewalk behavior and expectations about participation in community events. We gain an understanding of how it is possible to say that everyone in town is the same when there is actually almost as much inequality in small towns as in larger places. We see the enormous diversity of lifestyles, occupations, family arrangements, hobbies, and personal stories.

Townspeople are close observers of their communities. An outsider may gain the impression that small towns embrace a slower pace of life than in cities, but it is from townspeople themselves that we learn what a slower pace of life means and why it is valued. A public opinion poll may find that many Americans believe small towns are good places in which to raise children, but what that actually means to people living in small towns requires listening to parents’ accounts of their own experiences.6

How community is found in small towns requires paying attention as well to what it lacks. Rosy scenarios entertained by Americans who have never lived in small towns become more nuanced when townspeople themselves describe their communities. Residents are well aware of the challenges they face. When a store closes, the gap on Main Street leaves a psychological scar. Physical damage from a tornado or flood takes a long time to heal. Newcomers find it difficult to assimilate. The difficulties they experience have more to do with learning the subtle expectations of community life than with actually meeting people or making friends.

The hope that somehow America could regain a stronger sense of community if only it could revive small-town values diminishes when townspeople themselves share their insights. They are the first to argue that what happens in small towns is largely a function of size. Knowing one’s neighbors and being known in the community is limited by the size of a town’s population. It also matters that people work in town, share similar occupations and backgrounds, and above all stay for a while. These qualities are not easily reproduced in cities and suburbs.

Small towns are themselves undergoing change. Many are slowly losing population. Some are being absorbed into sprawling metropolitan zones. Others are adapting to immigration along with changing relationships among racial and ethnic groups. Better roads and easier transportation are turning some small towns into bedroom communities. The Internet and shifts in agriculture are reshaping their economic base. In out-of-the-way places one finds novel experiments with sustainable energy and new technology. Small towns are surprisingly resilient. While they preserve the past, they forge new connections with the future. Many of the residents who grow up in small towns choose to stay. Others choose to relocate from cities and suburbs in hopes of finding something lacking in those larger places.7

Asking why people live in small towns—and what it means to do so—is a bit like probing the reasons people become fundamentalist Protestants or orthodox Jews. These are the paths not taken by most Americans, especially by ones who consider themselves progressive, enlightened, and successful by worldly standards. The fact that millions of Americans do embrace conservative religious practices poses interesting questions about America as a society.8 Are there aspects of American culture that are truly not shared, or indeed that are rejected by a sizable minority? Or is conservative religion little more than an alternative lifestyle grounded in the same essential values shared by nearly everyone? Does it nevertheless matter what religion people choose? Are their chances of attaining education, working as productive citizens, and providing for their families impaired? Do they hold different political opinions and vote in ways that could affect the nation’s policies?

The decision to live in a small town evokes similar questions for our understanding of American society. The fact that most Americans live in cities and suburbs cannot go unnoticed by those who live in small towns. How does that knowledge of being in the minority shape their outlooks? Do they feel as if they are embattled, left behind, or ignored? Are they glad to be in the minority, and if so, what value do they place on having made this choice? Does it influence their politics, religion, or sense of what it means to be a good American?

There are ample reasons to think that residence is associated with distinct attitudes and beliefs. Political candidates say they represent the particular values of small-town America. Pundits sometimes argue that small communities are the guardians of homespun virtue. Maps of red and blue differences in electoral outcomes suggest that states dominated by small towns vote differently from areas populated by large cities. Small towns are stereotypically associated with conservative moral and political outlooks. They differ from cities in factors that further shape beliefs and attitudes, such as racial and ethnic diversity.9

Social scientists have been particularly interested in the historic differences between small towns and metropolitan areas. Max Weber, Emile Durkheim, Karl Marx, Alexis de Tocqueville, and Ferdinand Tönnies were among the influential nineteenth-century social scientists exploring these differences. Small towns emerged in these inquiries as places of traditional family values and strong social solidarity, but also as backwaters in the march of modern history compared with the advances of industry and population growth that were shaping cities and suburbs.10 American scholars in the twentieth century examined the decline of small towns along with the corresponding development of industry, business, ethnic enclaves, slums, the middle class, science, and education in cities. By the 1950s, attention had shifted increasingly toward questions about community life in suburbs.11

But relatively little research has been devoted to small towns since the 1950s. One reason is that cities and suburbs continued to grow and absorb most of the population growth from both natural increase and immigration. Questions of poverty, social welfare, racial discrimination, crowding, urban planning, housing renewal, and transportation all focused attention on urban areas. What had once been considered small-town virtues, such as warm community relationships, were found increasingly in suburbs, as were conservative political and religious values, which shifted the attention of political analysts to those locations. To the extent that they were lumped under the heading of rural America, small towns were viewed as part of a declining sector populated by fewer people, and of interest more as the location of food production and tourism than as places where people still lived. As a result, data have been available from census reports about the number, size, demographic composition, and economic characteristics of small towns, but little effort has been made to learn what residents of small towns think and believe.12

The fact that little research has been done does not mean that small towns have ceased to be of interest. Novels, movies, and television programs continue to present fictional accounts of small-town life. Journalists visit small towns in hopes of capturing a piece of Americana. Writers carry on the tradition of looking for down-home wisdom by talking to small-town sages and reporting on insights gleaned from living in remote communities. Increasingly the blogosphere has become a location of lively postings about the glories and deficiencies of small-town life.

From these various sources, two contradictory images of small-town America emerge. One is a nostalgic, almost-bucolic view in which towns and villages are dominated by warm neighborly relationships. The proverbial stranger who comes to town finds the townspeople at first a bit parochial, but then discovers them to be thoroughly good-hearted. The other view presents the small town as a place to leave as quickly as possible. The townspeople are unhappy, inbred, and reluctant to let go of the heroine who knows she must exit. The stranger who arrives is caught in a spiral of deceit and intimidation that cannot be escaped soon enough. In either case, the town serves as a convenient setting in which to tell of drama and intrigue, but there is little information about what the inhabitants of small towns are actually like.13

The research I present here was conducted principally through in-depth semistructured qualitative interviews with people currently living in small towns. More than seven hundred people were interviewed in three hundred towns scattered among forty-three states. The people we talked to included community leaders, such as mayors, town administrators, school superintendents, business owners, and clergy, who were knowledgeable about community issues, trends, and challenges, and could give us a bird’s-eye view of local events in addition to describing their own experiences. We also spoke with ordinary residents—farmers, factory workers, teachers, office managers, homemakers, and retirees, among others—who ranged from lifelong members of their communities to recent (or not-so-recent) newcomers. These townspeople supplied us with an exceptionally rich sense of what it is like to live in a small town and the various ways in which residents find community in these places. For comparative purposes, we also conducted interviews with people living in selected cities and suburbs. Additional information came from national surveys that measured attitudes about social, moral, religious, and political issues. Statistical evidence offers some indications about numbers of towns, changes in population size, and variations in occupations, incomes, education levels, racial composition, and age.14

The US Census Bureau estimates that there are approximately 19,000 incorporated places in the United States—a number that has edged up modestly over the past half century. Of this total, more than 18,000—or 93 percent of all incorporated places—have populations of fewer than 25,000. By that standard, almost 53 million Americans might be classified as living in a small town. Approximately 20 percent of these incorporated places, however, are located within an “urban fringe,” which the US Census Bureau defines as a contiguous, closely settled area with a combined population of 50,000 or more. Omitting those places leaves approximately 14,000 towns of under 25,000 people that are not part of an urbanized area. Almost 30 million Americans live in these communities.15

Besides towns that are officially classified as incorporated places, towns in New England and New York that are classified as “minor civil divisions” have functioned as local municipalities, usually with an incorporated name, town hall, governing board, and business district that give residents a distinct sense of their locale as a community. Examples include Canaan, Connecticut, a town of 1,200 some forty miles northwest of Hartford; Willsboro, New York, a town of 2,000 thirty miles south of Plattsburgh; Merrimac, Massachusetts, a town of 6,300 near the New Hampshire line above Boston; and Litchfield, Maine, a town of 3,600 located fifty miles north of Portland.16 In 2010, there were 1,723 of these towns with populations of fewer than 25,000 located in nonurban areas. Approximately 4.5 million people lived in these communities. When these towns are included, the total number of small towns in the United States with populations of less than 25,000 and located outside urban-fringe areas rises to 16,307, and the number of people living in these communities totals 33.7 million.17

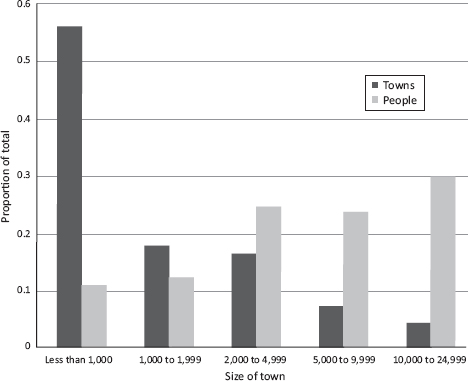

Of the nonurban places and minor civil divisions that might by this definition be classified as small towns, the majority of them are quite small. More than 9,000 or 56 percent have populations of under 1,000 people (figure 1.1). Another 16 percent have populations between 1,000 and 2,000, and an additional 16 percent have populations between 2,000 and 5,000. Only 7 percent have populations between 5,000 and 10,000, and only 4 percent have populations between 10,000 and 25,000.18

Most Americans who live in small towns, though, live in the larger of these communities. Twenty-nine percent live in towns of 10,000 to 25,000 residents. Twenty-three percent live in towns of 5,000 to 10,000 residents. Another 24 percent live in communities of 2,000 to 5,000 residents. Twelve percent live in towns with populations between 1,000 and 2,000. And only 11 percent live in towns with populations under 1,000.19

In sheer numbers, small nonurban towns of no more than 25,000 residents comprise 75 percent of all towns and cities nationally. That proportion is highest (exceeding 90 percent) in Alaska, Arkansas, Iowa, Kansas, Maine, Mississippi, Montana, Nebraska, North and South Dakota, Oklahoma, Vermont, and Wyoming, and lowest in California, Connecticut, Massachusetts, and Rhode Island. The proportion of people who live in these small nonurban towns (out of all those who live in any town or city) is highest in Alabama, Arkansas, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maine, Mississippi, Nebraska, New Hampshire, North and South Dakota, Vermont, West Virginia, and Wyoming, and lowest in Arizona, California, Connecticut, Florida, Massachusetts, New Jersey, Nevada, and Rhode Island.

Figure 1.1 Distribution of nonurban towns and people

When asked if they consider their community a small town, the residents we interviewed in nonurbanized towns of up to 25,000 mostly indicated that they did. Naturally, they drew distinctions between towns near the upper range and ones closer to the lower range. But the relevant comparisons that made them regard their communities as small towns were cities. The contrast in their minds was a place of several hundred thousand or larger. By that standard, their community was compact, self-contained, and more easily identified as a distinct place.20

Although the residents who live in small towns are well aware that their communities are indeed small, it is less apparent whether people who live in cities have a clear impression of small-town America. One impression is that small-town America exists geographically as well as culturally at a great distance from metropolitan centers. Perhaps it is located far away in a remote corner of the prairie or isolated section of hill country. It is true that an urban resident probably has to travel some distance before the city is left behind. But once out of the city, it is abundantly clear that small towns are still an important feature of the nation’s landscape. On average, there is a town of no more than 25,000 people every twelve miles nationally. States as different as Florida, Mississippi, Texas, and Virginia resemble the national average in this respect. In a number of other states, including Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Ohio, and Pennsylvania, there is a town on average every seven or eight miles. Only in sparsely populated western states, such as Montana, Nevada, New Mexico, and Wyoming, are towns on average more than thirty miles apart.21

The interviewees who participated in the research were selected to represent small towns of varying size. Nearly one-third lived in towns of fewer than 1,000 people. Another third lived in communities of more than 1,000, but fewer than 10,000 residents. Approximately 10 percent lived in towns of 10,000 to 25,000. And for comparison’s sake, approximately one-fifth lived in larger communities, of whom about half lived in towns of 25,000 to 50,000, and the remainder lived in larger places. The interviewees who lived in towns of under 25,000 residents were further selected by choosing towns that were located in nonurbanized areas. The mean distance from an urban area of more than 50,000 was sixty-seven miles and the median distance was fifty-four miles.

The interviews invited townspeople to talk at length as well as in their own words about how and why they had come to live in their current community, what their daily life was like, what they did for a living, their hopes and aspirations, and how they thought about the trajectory of their lives. Residents described their communities and the local ambience, discussed what they did and did not like about their towns, and told how they and their neighbors were faring financially. People talked about local politics, challenges and innovations in their community, and larger social and moral issues. The interviews with town leaders, clergy, heads of voluntary organizations, and local officials provided additional information about the beliefs, values, and meanings associated with living in small towns.22

The next chapter offers an initial view of the people who live in small towns, emphasizing the diversity of social strata of which small communities are composed. At the top are a small group of gentry, who in most towns consist of wealthy landowners, owners of successful businesses, and select members of the professions, such as doctors and lawyers. Next is a large service class that is generally college trained, and has increased in size as a result of the continuing need for schools in most towns and an increasing need for medical services as well as other services provided by businesses, and services offered through government agencies. The other large stratum consists of wageworkers who generally do not have college training, and are employed in manufacturing and construction jobs, or as office assistants and agricultural laborers. Small towns also include a sizable stratum of pensioners who are retired or semiretired, and are supported by Social Security, retirement plans, and part-time employment. With differences among social strata nearly as great in small towns as in cities, the question is why residents of small towns so often insist that everyone is the same. Chapter 2 examines the marks of distinction that residents use to describe social strata in their communities and discusses the local expectations that blur these distinctions.

The following two chapters take up the central question of how residents of small towns construct the meaning of their community in ways that reinforce loyalty to it and one another. Although the attractions of knowing neighbors and living in familiar places reflect common views about small towns, the evidence from residents themselves points to the need to pay closer attention to what these attractions actually mean. Chapter 3 looks at what people mean when they say a small town offers a slower-paced life or more authentic place in which to raise children. That chapter demonstrates that residents are fully aware of the disadvantages of living in a small town, and shows how residents compensate by, for example, organizing local cultural events and traveling more frequently to cities. It concludes by considering the challenges residents talk about as they see their communities changing. In many towns, immigration and new ethnic diversity are the principal changes on residents’ minds. In many others declining population, diminishing services, and lower standards of living are the major concerns. Understanding what leads people to say that their communities are dying or were better in the past than now, or deny that these changes are taking place, requires going beyond population statistics. The chapter shows the particular events that residents associate with decline, and how they make sense of departures and loss.

Chapter 4 explores in further detail what residents understand as the most important sources of community spirit in their towns. Although it is widely believed that small towns do encourage community participation, scarcely anything has been studied about the meanings of community spirit or its sources in towns’ activities, such as homecoming weekends, athletic events, and community festivals. The chapter examines how narratives about the goodness and decency of a community are formulated, and how they reflect special occasions in which personal or collective tragedy is overcome. A key part of community spirit is the perception that acquaintances in town are in fact good neighbors. How neighborliness is demonstrated even through small greetings and sidewalk behavior is the secret behind these perceptions. The extent to which these expectations are taken for granted nevertheless poses difficulties for newcomers, and these inhabitants are a critical source of insight about what they have learned in attempting to adjust to local norms.23 The chapter ends with a discussion of the stories that townspeople tell to combat negative stereotypes imposed on them by city people along with tales that emphasize the relative freedom, openness, and closeness to nature that small-town life provides.

Chapter 5 moves from a consideration of the perceptions residents have of their communities to a look at the ways in which residents in small towns make sense of their own lives. The chapter contends that small communities create a frog-pond identity that residents draw on to formulate narratives about why they chose to live in a small town, how that choice has limited or enriched their career opportunities, and whether they feel regret or are satisfied. Residents do describe a number of ways in which being raised in a small town or choosing to live in one has restricted their chances of getting better jobs and higher pay. Equally important are the justifications residents provide to explain these limitations. Personal networks, family loyalties, and a lack of guidance about higher education decisions are commonly mentioned. In addition, narratives sometimes emphasize the desire for a balanced life that includes time for family and friends, or a sense that a more authentic life can be found for oneself and one’s children in a small town. Although townspeople generally include choice in these narratives about where to live, a significant number of them acknowledge that they live where they do because of unforeseen circumstances and events over which they have little control. These choices and circumstances are often portrayed differently by women than by men, leading the former especially to underscore being good wives and mothers as substitute gratification in view of opportunities foregone. The legacy of farming also has a considerable impact on the lives of small-town residents. Although the farm population itself has declined considerably over the past two generations, the impact of having been raised on farms or expecting at some point to take over farming from parents and grandparents remains crucial.

The next two chapters focus on the town leaders and associations that play key roles in small communities’ efforts to adapt to changing social and economic conditions. Chapter 6 examines formal and informal leaders, including local public officials and heads of voluntary organizations. It shows how residents confer respect on leaders and how leaders draw on this respect in performing their roles. Leaders discuss why they take on civic responsibilities, the gratifications and frustrations involved, and how these activities serve as stepping-stones for public office in larger venues. Although small towns are sometimes considered to lack interesting cultural amenities, local cultural leadership is particularly important, and figures prominently in communities’ understanding of their distinctive history and identity. Small communities have high expectations about the need to attract new residents and jobs, and hold on to local schools and businesses. But leaders with experience in meeting these expectations note resistance to change, and argue that smaller-scale and more realistic programs are better suited to their communities. Small towns nevertheless are laboratories for social innovation, judging from leaders’ descriptions of new technologies, electronic communications, sustainable energy projects, and efforts to rebuild following natural disasters.

Chapter 7 considers the roles played in small towns by religious organizations. Although it is the case that religious participation is somewhat higher in small towns than in larger communities, the differences are relatively small. The perception among residents that religion is important has more to do with the presence of religious buildings along with the public activities of religious organizations than with statistical measures of belief and practice. Religious organizations also serve significantly as carriers of collective narratives about caring behavior in the community, and these organizations increasingly provide links between small towns and the wider world through mission trips as well as humanitarian and relief efforts. In small communities with declining populations, religious organizations are adapting in creative ways to meet the needs and interests of their constituents. The clustering of congregations, shared pastorates, mergers, and church closings are among the solutions that are being attempted.

The following two chapters examine how social and political issues are framed in small towns. Chapter 8 shows how perceptions of moral decline intersect with the reality of living in towns with declining populations and diminishing job opportunities. The specific moral issues of concern that residents of small towns most frequently mention are abortion, homosexuality, and schooling issues, such as teaching the Ten Commandments and the biblical creation story alongside evolution. Although residents take different perspectives on these issues, the conservative side is more commonly featured in public discourse and includes a rhetorical style that makes it easier for this to happen than for a discourse to be emphasized that focuses on personal choice.

Chapter 9 demonstrates that antipathy toward big government is inflected in several ways among residents of small towns. These ways include concerns about the scale of big bureaucracy, its inability to adapt to the particular norms and practices of small towns in which people know one another, and government’s unresponsiveness to the needs of small communities in comparison with its attentiveness to problems in cities. Antipathy toward government is further reinforced by negative opinions about people on welfare. Compared with perceptions of state and federal government, attitudes toward local government are typically more charitable, but register conflicts as well. With residents of small towns on average being only slightly more favorably inclined toward Republican candidates than Democratic ones, Republicans nevertheless seem to be better represented in many small towns. The chapter discusses the reasons for Republican popularity and concludes by considering the possibilities present in small towns for grassroots populist activism.

Chapter 10 delves into an aspect of small-town life that generated almost more anxiety than any other in our interviews: the future these communities may—or may not—hold for the next generation. As residents nearly always see it, young people who grow up in small towns should go to college in order to be well prepared for whatever the future may hold. Once again, though, the reasons given along with the concerns underlying these reasons are more complex than broad-stroked surveys and census data reveal. Although they consider higher education critical, residents—parents and educators alike—acknowledge that there are aspects of small-town culture that make it difficult for young people to plan appropriately in order to make the most of college or university training. Some worry about pressures to marry young, while others identify a lack of self-confidence as the most serious disadvantage. Variation is also present in the goals that residents consider important in advising young people about the future. One of the most interesting narratives that surfaces in these interviews emphasizes the need to take one’s community values along, no matter where one lives—and for those who remain in a small town to keep their options open.

In the final chapter, I offer reflections that pull together my observations about the various factors that contribute to residents’ sense of community in small towns. I draw from Suzanne Keller’s ethnographic study of community life in which she identifies ten key building blocks of community. These include tangible aspects of social relationships that have been of interest to students of social capital, especially social networks, sharing, and cooperation, but also stress territory, governance, leadership, rituals, and the beliefs, values, and norms that guide behavior.

Running through all these topics is a larger observation to which I repeatedly return. The meaning of community in small towns is a bit like common sense, which as Clifford Geertz once noted, “lies so artlessly before our eyes it is almost impossible to see.”24 I had that sense more than once while doing the research and was reminded of it especially when a scholar known for a career of studying community asked why I thought it should be studied in small towns at all. “Everyone knows there’s community in small towns,” he said. True enough, but shouldn’t that make it all the more important to find out what community means?25

And the answer to that question is not to carve up meanings into large digestible chunks—not to create boxes of typologies in which to categorize the complexities of small-town culture. It is rather to analyze how the reflexive self-awareness of living in a small community figures into the language in which residents characterize their lives. Viewed in this way, community is not only a place of residence or set of social networks but also a component of a person’s worldview. Being part of a community—living in a small town—commands a place as part of a person’s self-identity, just as a person’s race, gender, occupation, national origin, or citizenship does.

From examining the taken-for-granted self-perceptions of people who live in small towns, we see that their awareness of this fact shapes how they understand the distinctions that define and separate social strata. Being fellow members of a community offers a way to see the relationships among strata and level the differences. Community mindedness further inflects the meaning of disparate experiences and values, such that the pace of life, distances, entertainment, authenticity, children, and neighborliness are all perceived through the lens of living in a small place. This is also the case with understandings of the frog pond in which career choices and the meaning of money are interpreted. It infuses particular valences into moral, religious, and political sentiments.

None of these observations is meant to imply that outlooks in small towns are fundamentally different from attitudes in cities and suburbs. There is good reason to believe, as scholars have argued, that television, advertising, ease of travel and communication, geographic mobility, and even standardized food processing—McDonaldization—have all contributed to a common culture that includes small towns and rural areas as well as cities and suburbs.26 The point is rather that community has specific meanings in different places, and some of what makes these meanings special is the size as well as location of the place in which a person lives. Understanding community requires paying special attention to what it means to the people who live there. The task is like understanding motherhood. It may be universal, but its meaning varies from person to person, and has value precisely because of those variations. In real life, people define themselves by weaving narratives that give coherence to their day-to-day experience. Community is significantly—and for most residents of small towns, deeply—woven into these narratives.27 In small communities, the intuitions and emotions, personal accounts and town legends, routine sidewalk behavior and annual festivals, interweaving of family history and neighborly relations among the people who live there all converge to forge an almost inexplicably powerful attachment.