The Frog Pond

Making Sense of Work and Money

A STANDARD INTERPRETATION OF THE AMERICAN dream holds that it is all about achieving success. The path to success involves getting as much education as one can, finding a rewarding career, and moving up the ladder as one gains greater skills and matures. A successful person is expected to move from place to place in search of career opportunities, rather than becoming too attached to their community, and work hard and attain specialized knowledge that is rewarded in a competitive market. Success may not come in the form of an extremely high salary or powerful position but instead is attained, usually in comparison with one’s parents, by taking advantage of the opportunities at one’s disposal, wherever they may be. When asked to account for success, people usually tell stories about working hard, knowing the right people, and being willing to take risks. Apart from the occasional military hero or explorer, people who attain the American dream usually pursue it in cities. These are the locations of the most specialized organizations, largest markets, and best job opportunities.1

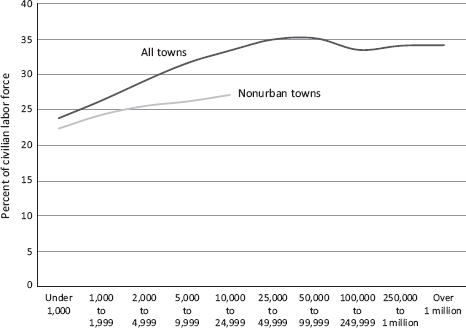

Small towns are the place to examine a different kind of story. People in small towns know it is unlikely that they will ever become rich living there. Job opportunities are limited.2 Many lines of work that might be interesting are simply unavailable. This is especially true for people seeking employment in the professions or managerial occupations. The likelihood of being employed in those occupations is significantly lower in small towns (and even lower in small rural towns) than it is in larger communities (as shown in figure 5.1).3 Choosing to remain in a small town or deciding to move to one is tantamount to saying that some other goal in life is valued more highly than becoming a huge success. Instead of pursuing all possible opportunities to get ahead, the person makes other choices, perhaps intentionally settling for less. The person who stays in a small town is in this respect deviant, perhaps not in happiness or even earnings, but in bucking the national trend of living in cities and suburbs.

Figure 5.1 Employment in professions and management

A small-town person’s siblings, children, and childhood friends are likely to include people who have moved to a city or suburb.4 Thus, the interesting question to ask is how people explain their choice not to pursue the American dream the way those relatives, friends, and indeed many other people do. How do they account for living in a place that likely offers them fewer opportunities than if they had opted for a larger community? Do they feel they missed the boat somewhere along the way? Did they make the wrong choices? Were there overweening circumstances? Were other values—perhaps the desire for a more intimate community—more important?

As I reflected on people in small towns discussing their work and livelihoods, the first thing that struck me was that their aspirations were often rather modest. I was used to teaching Ivy League students who wanted it all. Many of them had been striving earnestly ever since they were in preschool to be the best at everything: spelling, math, soccer, and violin. They were programmed to achieve. They had in mind that when they graduated, they would do whatever it took to continue getting ahead. They would specialize, get into the best graduate programs or law firms, and move anywhere to attain the best job possible. This was not the way people in small towns talked. They were not driven to become the smartest chemist in the country or most successful trader at Goldman Sachs. Their stories were quite different, focusing as much on families and communities as on competition and success.

In reality, few Americans actually attain the proverbial dream of moving up from rags to riches. Whether they live in small towns or large cities, about 99 percent of the public know they are never going to be rich. Success comes in smaller doses and is measured differently. It involves adjusting to the unexpected circumstances of life, the situations that a person cannot control, and learning to find happiness amid these situations. In this respect, the stories people in small towns tell about their livelihoods are probably a better window on US culture writ large than the accounts given by the rich and famous who we so often hold up as models of what success should be.

It is probably wrong, when one considers it more carefully, to think that people in small towns differ fundamentally from people elsewhere in how they decide on careers. Nevertheless, it is the case that the scale of one’s community can have a decided effect on the scope of one’s aspirations. The influence can be understood as a frog-pond effect. For some people, being in a small frog pond works to their advantage. They can be the best student in their class or the best football player in town, and that sense of achievement gives them greater confidence than if they were in a larger place. In many instances, people in small towns insist that they chose their line of work because it indeed fulfilled their aspirations and utilized their talents. There are instances, though, where being in a small town discourages such pursuits. People say they did not have good role models or could imagine only a few occupations because those were the only ones evident in their town.

In effect, their frog pond limited their horizons. They became involved in their line of work less because it enabled them to realize their talents and more because it seemed like the only thing they could do. “I wanted to be a teacher,” a man in his sixties recalls, but in college he tried to explain calculus to some of his fellow students and immediately became frustrated. Blaming himself and suffering from self-doubt that he associates with having grown up in a small town, he says, “A light went on one day, and I realized I couldn’t explain anything to anybody. How could I ever be a teacher?” From that moment on, he shifted his sights toward returning home and working at something else. He has enjoyed living in a small town. And yet his understanding is that it was the default option left to him because he was unable to teach. His small-town background figures into his account at several levels, providing a reason for his self-doubt and an explanation for his choice of career.

This example illustrates the kind of thinking that needs to be considered to make sense of the relationship between living in a small town and residents’ attitudes toward work and money. The issue is not only that people in small towns earn less money on average than they might by living in a city. It is not that they are more likely to be employed in agriculture or small businesses than in large corporations. It is rather that community is an important part of their story.

“We always have options in telling a life story that makes sense to us,” philosopher Seyla Benhabib writes, but these options are “inflected by the master narrative of the family structure and gender roles in which each individual is thrown.”5 And by the places in which one lives, I might add, especially if that place is a community where narratives of why its residents have chosen to live there walk the streets and fill up gatherings on rainy days at the grain elevator.

Townspeople tend not to talk about work and money solely in the idioms of career interests, job security, or opportunities for advancement. Choosing where to live is a significant part of how they tell their story. Individualism in the sense of freely making choices and independently pursuing happiness is very much present, as observers of US culture so often emphasize in other contexts. But being part of a community also matters to these residents. How exactly they factor it into their thinking is the question I want to consider here. For example, do they view their commitment to living in a particular kind of community as a significant sacrifice? Or do they find ways to reconcile individual interests with living in small places? And what special issues arise for women, people whose lives have been significantly disrupted, and the offspring of farmers?6

RESTRICTING THE RANGE OF OPTIONS

The frog pond performs the key function of limiting choices. An abundance of opportunities to choose from may be desirable, but its downside is that having so many choices can be overwhelming. Identifying with a particular frog pond narrows the options. Deciding on a college major does that. Choosing to follow in a parent’s footsteps does so too, as does living in a small town. A good example is a twenty-two-year-old who lives in a town of about a thousand where the best excitement on weekends is at the quilting shop and fishing pond. In high school he imagined himself going away to college, learning textile management, and pursuing a career in the city working in the fashion industry. But in college, he suddenly found his horizons widening to include a dizzying array of possibilities. Performing well in all his courses, he realized many career options were possible. The question of what to do with his life was so acute that he began having panic attacks and decided to come home for a semester to figure things out. Some of his mother’s friends in town were renovating an old building and hoping to turn it into an antique store. Without thinking much about what he was doing, he started helping them and found it enjoyable. Now two years later, he thinks he will stay in his hometown, work at the grocery store, and see if he can start a nonprofit business. He repeatedly mentions the “handful of people” there in his hometown who seem to share his values. It feels good to him to have settled into something he likes rather than having to think about so many different possibilities. “Every once in awhile you think, ‘Well, what if,’ ” he says. “But you can’t ‘what if’ all your life. You have to go forward.” At least at this point in his life, he is able to go forward because his hometown has limited the choices he has to think about.

The decision to return to one’s hometown is quite different for other people than it was for this young man. In other cases, the familiar frog pond serves less to restrict a perplexing array of possibilities in the wider world than as a safety net when other options prove unworkable. A man who is now in his forties and still living in the town of twenty thousand where he was raised recalls his decision after a year away at college. Growing up in a town where the dominant Anglo population often discriminated against Hispanics, he had struggled in school. His parents nevertheless understood that education was the ticket to a better life and insisted he go to college. Unable to make passing grades, his only option was to return home. After working at several different low-paying jobs, he tried going away to a junior college, but again failed to make the grade. Back in his hometown, he got a job at an electronic goods and appliances store. The owner offered to pay his way at a nearby vocational technical school where he could learn to repair electronic items if he would promise to continue working at the store for seven years. Seven turned into fifteen, and what had begun as a safety net turned into a life. He has married, raised a family, and shifted to a larger store. In his spare time he does volunteer work to help improve relations between the Hispanic and Anglo population.

Many of the residents we talked to in small towns have had limited career options because they grew up on farms or in working-class families, and were raised by parents who could not afford to send their children to college or set them up in business. In rural communities, the transition is often from marginal farming and part-time off-farm work into full-time wagework as an unskilled or semiskilled employee. Mr. Yeager, the factory worker we met in chapter 2 who lives in a town of thirteen thousand with his wife and three children, is an example. His father grew up on a farm, and struggled to keep the farm in the family by tending crops and livestock in the evenings and on weekends while working full-time at a plant that manufactured telephone wire. Mr. Yeager is in a sense following in his father’s footsteps by working full-time at a manufacturing plant. The difference is that Mr. Yeager has no ties to farming. His life is also similar to his parents in that both his wife and mother worked outside the home.

As manufacturing has diminished in small towns like Mr. Yeager’s, a more typical pattern is for sons and daughters of marginal farmers and working-class families to move directly into service jobs. If they were fortunate, they married someone who could be employed in a profession, such as teaching or accounting. An example would be Delores Barnes, a woman who grew up in a town of two thousand people. One of four children, she was raised mostly by her mother, who worked as an aide at the local hospital. Her dad was an oil field worker who drank too much and abandoned the family when she was in junior high. Her mother struggled to make ends meet but never took assistance from anyone. When Delores graduated from high school, she worked her way through a secretarial course and managed to finish a year of college before quitting to get married. Her husband became a teacher. His parents had not been to college either, but were a little better off than hers financially. His dad worked for the utility company and his mother was a nurse. Delores’s husband finished college, and took a job teaching and coaching. Over the next twelve years they had three children and moved several times before settling in their present location. They now live in a town of seventeen hundred.

Mrs. Barnes works at the bank and sells insurance on the side. Initially she figured she had two choices. She could be a hairdresser or secretary. The former appealed to her artistic side, but she opted for the latter because it paid better. She worked part-time when the children were little and then started at the bank when the youngest was in school. It was the perfect job. She was through at 3:30 p.m. when the children came home from school. It was a block from her house, provided health insurance, and she could take the day off if one of the children was sick.

The small-town frog pond has worked well for Mrs. Barnes. She says she could have lived in a city, and in fact, she and her husband did live in a city one year when he was going back to school to get more education, but they preferred a smaller place. They like the “slower-paced way of life,” she says, and the schools are good. Coming from a family with a meager income, she figures she would likely have wound up working in a clerical job similar to the one she has even if she had finished college and moved to a city. The one dream she knows she will never fulfill is to own a business of her own. The dream she is proudest of is raising three children who are now happily married.

Between her husband’s salary teaching and hers at the bank, Mrs. Barnes feels they live comfortably, even though they might have earned more living in a city. Housing is cheap, and there are not many diversions that require a lot of money. Nothing about the small town has stood in the way of pursuing her hobbies, now that she has more time. Working at the bank and being a teacher’s wife means she has plenty of opportunity to make friends. She serves on several community-wide committees and is active at her church. As an expression of her artistic interests, she hosts jewelry parties for women in town. The one challenge is that she is starting to learn to play bridge. That is a challenge because the bridge players in town are all much better than she is, but she has found a solution. She plays bridge with other beginners online.

Mr. Keller, the medical clinic director we met in chapter 2, tells a similar story. In the town of twelve hundred where he grew up hardly anyone had been to college. Certainly nobody in his family had. His father worked long hours on the maintenance crew for the state highway department. His mother’s family members, he says, were “gypsylike folks” who moved around and took whatever jobs they could find. He was more fortunate than many of his high school classmates in being able to go to college. Coming from a lower-income background did not hinder his opportunities in that respect. But it did make it harder for him to know what to do in college or think about a career. Unlike college students who had relatives and family friends in science and engineering, or worked for large corporations, he had no way even to think about such possibilities. His frame of reference was the small town. Deciding that he might be able to work at a health clinic in a small town was an idea within his reach.

Ironically, young people whose small-town parents most seriously want them to go to college—and indeed, who make significant sacrifices to provide these opportunities—sometimes confront an unexpected limitation. What their parents want most is simply that their children get a college education. Naturally they are supposed to major in something practical. But their parents, who probably have not gone to college themselves, have bought into the idea that college, period, is the path to a better life, and thus have little sense of how to think more specifically about choices among colleges and possible majors. As one woman explains, her parents “felt that college education was the way to go and urged all of us to go to college,” but she adds, “The choice of college and the choice of curricula were totally up to us.” At the time, that seemed terribly liberating. Yet in retrospect it was a disadvantage. Unlike youths whose parents worked in the professions, understood the intricacies of different college majors, and lived in communities with larger high schools and better career counseling, these young people were left with little specific guidance.

A small hometown can serve in such instances as a psychological refuge. Although it is rare for small-town residents to say straightforwardly that they were afraid to live elsewhere, they sometimes acknowledge that they found it easier emotionally to stay than to leave. Paul Genessee, a man now in his forties whose education stopped in twelfth grade, is a case in point. He is unmarried, lives in his hometown of twelve hundred, and drives twenty miles to a larger town where he works as a typesetter at a print shop. He says he planned to go away to college, but backed out at the last minute. “I was a little bit afraid of leaving, of getting too far away from home, so I just started working instead,” he recalls. In retrospect, he wishes he had moved out of state and gone to college. “Finding out what it was like elsewhere and being glad to be back,” he says, would have been better than “wishing I had done it back then.” He feels it would have been difficult, though, at eighteen to adjust to some other location. He was not much of a people person, he notes, and his mother pressured him to stay home a lot. What he likes most about his hometown is feeling peaceful, quiet, and safe.

The sense, as Mr. Genessee puts it, that a person living in a small town is happier having tried living elsewhere reflects the broader value that Americans place on moving away from their parents, becoming independent, and seeing the world. It is more acute for a man like this who lives in a small town because he feels himself having failed to be as competent as he should have been. Had he lived elsewhere, he could persuade himself that his decision to return to his hometown was made from strength rather than from weakness.

The contrast is evident in the remarks of Sheila Wilkes, a woman in her forties who lives in her hometown of six thousand. While she was growing up, she wanted to marry someone from her hometown and spend her life there. She especially identified with her mother, whose ancestors were among the town’s earliest settlers. It was comforting being among aunts, uncles, and cousins. After two years of college, she came home and worked at the local radio station. But she moved to a city in another state after a few years and there met her husband. Now, back in her hometown, she feels no sense of weakness for having returned. She simply feels that this is where she is meant to be. “It’s the way I was raised,” she says. “These are my people.”

For residents like Mrs. Wilkes, it matters to be able to say that they tried living elsewhere and chose to return. Having made this choice, they are also able to compare how they felt living in a city with how they feel now. The frog pond figures into this thinking as well. A person living in a small town might feel that what they do is insignificant—at least compared to the movers and shakers who exercise influence in large cities. But as frog pond, the reference point becomes the town. A sense of personal efficacy is the result. “You get involved in things and feel you are making a difference,” one woman explains. “In a small town you get to see the final outcome.” The outcome may be babysitting a neighbor’s child and being present years later when that young person graduates from high school, helping plant flowers at the library, running a small store, or working at the courthouse. Living and working in the town as well as spending most of one’s time there reinforces the conviction that what one does matters. Being involved in the community means that a person’s story is interwoven with those that neighbors tell about who does what in the community. People may not “blow their horn,” as the saying goes, but they know that word spreads about what they do.

Although few people say they would live differently if they could do it over, a number of the older people we talked to did register some regret as they reflected on the decisions they had made early in life. They feel that they were probably too cautious back then and passed up opportunities for fear of taking risks. True, they often had not had many opportunities and they did the best they could. But they blamed themselves for thinking too small.

I introduced the Bradfords in chapter 2 as an example of a couple living comfortably in a small town on a teacher’s pension and some rental income from a farm. Mr. Bradford says his parents struggled to make ends meet during the Depression and passed that sense of insecurity on to him as he was growing up. Mrs. Bradford’s father, the cowboy, was more successful financially, but he worried a lot about the possibility of losing everything. Both Mr. and Mrs. Bradford are proud that they have worked hard all their lives and have lived frugally. Like many people with modest incomes, they say it is better not to have been rich because wealthy people are no happier than they are. In fact, they point to a rich family they know whose children were spoiled and now as adults are lazy. Despite being content with their lives, the Bradfords nevertheless wonder if they limited themselves unduly by narrowing their horizons. “I took life as it was and didn’t really dream,” Mrs. Bradford says. Mr. Bradford remarks, “I had a lot of opportunities that I let slip by because I was afraid to try some things. I was afraid to fail.” “We both have been guilty of being in our little rut,” Mrs. Bradford adds, “of not expanding our lives more than we have.”

An attorney we talked to in a town of twenty-five thousand expressed ambivalence similar to the Bradfords even though his income was much higher than theirs. Although he was one of the more prominent citizens in his community and had experienced reasonable success in his career, he thought his imagination had been limited by growing up in a small town. His parents had actually lived in several states while he was a boy, and the family had even lived in a large city for a couple of years. Looking back, he remembers neighbors in the city who had never been anywhere, but he thinks he might have explored wider opportunities had he spent more of his life in a city. “I’m not a bumpkin,” he says, “and I don’t mean to frame myself as one. But I’m a little concerned that maybe I haven’t branched out as much as I could have or perhaps should have.”

The common factor in these stories is that the frog pond has defined the range of career options people considered. This influence is more than strictly psychological. It is rooted in social networks. Studies of how people find jobs show that social networks are a decisive influence. Weak ties, such as a friend of a friend or a distant relative, are especially important.7 The people we talked to who stayed in small towns generally did so because of social networks. Sometimes these networks involved weak ties, such as hearing about a farm for sale from a distant cousin or attaining a job at a local business through the parents of a high school friend. More often the ties were strong, such as taking over farming from one’s father or wanting to live close to one’s widowed mother. When people moved away, networks played an important role as well. For instance, a doctor who grew up in a small town says he was able to live rent free during his first year of medical school with a friend that his father had known in college. Others from small towns tell of visiting relatives in the city to learn about jobs, receiving help from neighbors while they were pregnant or their children were small, and following in the footsteps of older siblings in going away to college. It is the fact that these networks are shaped by their communities, which in turn stamps not only the aspirations of residents but also their opportunities.

IN QUEST OF A BALANCED LIFE

In social science terminology, the American dream is a cognitive framework or schema that arranges bits and pieces of experience into an intelligible pattern, much like the simple unconscious schema does that allows us to recognize faces. The difference is that facial recognition schemata are hardwired, rooted in simple perceptions, and learned early in life, while the American dream is picked up over a longer period through cultural exposure, such as hearing parents, teachers, and guidance counselors talk about success.8 Much of the imagery of which the American dream is composed consists of vertical metaphors. A person moves up the corporate ladder, earns a higher salary this year than last, and achieves above anyone’s expectations. Failure is described in opposing metaphors. The lack of success is tantamount to falling below expectations, earning a lower income, and in the worst case being down and out. It is almost impossible to talk about success without using these metaphors. A vertical scale makes for ready comparisons between ourselves and others, and between the present and past.9

But vertical metaphors also are how we think and talk about balance. Justitia, the blindfolded Roman goddess of justice whose image can be found in many US courtrooms, holds a scale that serves as a measuring device to weigh the relative merits of opposing values. Balance is indicated by the height of the pans on either side of the fulcrum. Height on one side may suggest that value has been sacrificed on the other side. To bring about equilibrium it may be necessary to give up some of what has been accomplished on the high side to bring up the lower side. Similarly, the American dream implies that gain in one area of life is accomplished by incurring a deficit in another area. Earning a higher salary means expending energy by working hard and thus giving up leisure time. Moving up in one’s job may mean lowering one’s expectations about living close to one’s parents or taking long vacations. The narratives used to make sense of work and money include such images of trade-offs and balances.10

The frog pond is a horizontal metaphor, flat, defined by length and width more than by height. An understanding of balance requires paying attention to the horizontal dimension as well as the vertical scale. An aspirant for an Olympic medal competes in a global frog pond. Among Olympic competitors balance in life is likely to be heavily tilted toward practice, strength, proper training, and a good diet. Institutions of higher education function similarly as large frog ponds, recruiting staff and students nationally and internationally in the name of excellence as well as diversity. Small towns establish a delimited frog pond in which the range of career options is necessarily restricted, leaving room for clearer considerations about alternative values.

The quest for balance is the key to understanding how residents of small towns frequently think about their communities in relation to their work and money. Consider what Mr. Parsons, the loan officer we met in chapter 2, says about his choices. “I can tell you I have been offered a lot better positions and a lot more money in the banking industry to go to bigger communities, and I’ve turned them all down. My wife and I decided way back when we got married that we were not going to live in a larger community.” The trade-off he describes is completely straightforward. The value that he and his wife place on where they live justifies the sacrifice of a higher income. Exactly why that trade-off makes sense is clarified by what he says next. “We were going to raise our kids in a small community.” It was not the small town per se that mattered for the Parsons but instead their sense that children would be safer, happier, and better rounded in that context.

If it is the quest for a balanced life that motivates people to give up something in order to live in a small town, then it is important to understand in closer detail what makes that trade-off attractive. Mr. Parsons’s emphasis on family fits well with results of other research showing that it is not the American dream of success as much as it is the ideal of being a responsible breadwinner that shapes popular thinking about work and money.11 The breadwinner works to provide for their family rather than to achieve success for its own sake. Breadwinning suggests a focus on money that will secure a comfortable home and good education for one’s family. A broader view of breadwinning, though, would have to include location. A breadwinner might choose to work at a high-paying but frustrating job in order to live in a good school district, for example. In Mr. Parsons’s case, the decision was to work at a less remunerative job in order to raise his children in a small town.

The breadwinner is sometimes described by social scientists as a person who sacrifices personal aspirations for the sake of their family. In this view, the breadwinner grudgingly gives up the chance to pursue a more fulfilling or remunerative career, and maybe even passes up opportunities for enjoyable avocational interests to feed and clothe the family.12 Psychologically, there is not much to be said for it. But consider the story that Mr. Parsons tells about why his life is fulfilling. “I hired a friend of mine who was a contractor.” This is how the tale of building his garage began. “He’s a farmer but he’s got a degree in, I think he could be a shop teacher, or whatever, and he did a lot of construction. And between my sons and him and I, we built it ourselves. I wanted to experience that. I wanted to be able to go out and buy the materials. I enjoyed that. I just didn’t say, ‘Build me a garage.’ I was involved with a lot of the planning, a lot of the purchases, and stuff, but that’s the way I wanted to do it. It took us a long time to get it done, but we really enjoy what we have.” He likens this to the satisfaction he receives from his family as well as living in a small community. Balance in life is not just about sacrificing an interesting career for one’s family but also is achieved by scaling back on specialization and efficiency. It involves developing multiple skills, working with one’s family and neighbors, and accomplishing something of modest proportions slowly and deliberately.

Mr. Cranfield, the man we met in the last chapter who values the balanced social relationships of a small town, is illustrative of a similar logic. In his case, it was a considered decision to live poor and grow apples in order to have a simpler life. That is the trade-off he values. But he also thinks living in a small town helps in trying to achieve that balance. Because nobody in his town has much money, and indeed quite a few are poor, he finds it easier to feel comfortable about what he has. He thinks there is less conspicuous consumption than in cities. Townspeople would look askance at someone who flaunted their wealth. It also helps, he supposes, that consumer goods are simply less available. “You can’t buy stuff,” he says. You would have to drive fifty or a hundred miles to buy something that would be more readily available in a city or suburb.

The scale of a small town establishes a kind of symbolic boundary around a person’s aspirations. It says, realistically, this is what I think I can achieve. Within this orbit of accomplishment, I will be content with whatever happens because other sources of satisfaction are present as well. I can enjoy my family and neighbors, learn new things, avoid becoming overly specialized, and escape the pressure of always striving for more. This is how the American dream is understood at the grass roots—at least by many of the residents we talked to in small towns. It may be nice to imagine that anyone can join the ruling class, but in reality we know that time, health, other values, financial constraints, and accidents of birth establish the parameters of success. It is not so much a matter of setting one’s sights low but rather of being realistic.

Ms. Clarke, the county agent, expresses this notion of being realistic particularly well. “I was born somewhat of a realist,” she says, “so there were certain things that I really enjoy that I just knew never would be. I like vocal music. If I could have been anything in the whole wide world, I would have been a country music star. I don’t think I have the body or probably even the voice or definitely the drive to want to scrape by for that particularly long and maybe never make it.” She enjoyed vocal music in high school. The state competitions served as a kind of frog pond in which she could compete, but also showed her that she probably would not do well in music on a wider scale. Now she is content singing in her church choir. She thinks about money the same way she does about music. As high school valedictorian, she could have opted for a career in which she could make a lot more money than she does now. “If money were a big issue,” she laughs, “I certainly wouldn’t be a county extension agent here in this town.” But the community gives balance to her life. She enjoys being connected with agriculture, living within an hour or two of her parents and siblings, and having a prominent role in her town.

LIVES INTERRUPTED

If people who stay in small towns or move to one in quest of a balanced life constitute one category, a different trajectory is represented by the many people who wind up in small towns through unexpected circumstances. An unplanned pregnancy, a divorce, an illness, losing one’s job, lacking money to finish college, the death of a parent, or simply not knowing which direction to take in life are all among the unexpected circumstances that shape where and how a person lives. Much is written about the unanticipated setbacks that cause families in cities to fall into poverty. Usually the story is about mothers and children on welfare or existing on minimum wage jobs. Often the story is of families living in substandard inner-city housing.13 But there is another category of people who are frequently overlooked. These are people who might well have pursued ordinary middle-class careers from homes in suburban housing developments had it not been for some unexpected event in their lives. The college major they planned on proved ill suited to their interests. The marriage they vowed to keep for life fell apart. A widowed parent needed their help. They did not end up in unemployment lines or welfare offices. They instead found themselves living in a small town where housing was cheap and a job was available. Perhaps they returned to their hometown where they could rely on help from parents and siblings. Perhaps they retained ties to the city, commuting there for employment. These are people who by all objective accounts failed to achieve what they set out to be. Living in a small town was Plan B. And yet through a series of adjustments, they came to make a small town their home.

US Census data and surveys do not begin to tell the story of how unanticipated events channel people into jobs and places to live they never expected. In our interviews, we encountered numerous instances in which happenstance events of this kind played an important role. Tragedy struck. A business closed. A child died. People changed course because they had no other choice. Or they moved seeking refuge from painful memories. The point is not that small towns are any more likely than cities to be populated by people whose lives were interrupted. It is rather that small towns include people who never expected to live there and really would have preferred to be somewhere else. For them, adaptation is often difficult. The small town is appealing because of family ties or as an escape from an even harder situation in a city. And yet the drawbacks are fully apparent. The possibility of what might have been tugs at people’s hearts.

The story of Allison Willard is fairly typical of people we encountered in small towns whose lives had led them there by a circuitous route. She lives in a community of a thousand people more than a thousand miles from the city where she grew up and expected to spend her life. As a teenager, she planned to become a mother after high school with a traditional woman’s job as a secretary or nurse. “But then all of a sudden everything changed,” she remembers. “I really didn’t have a clue who I was going to be.” She quit school, found a job, and got married. At twenty-seven, she was a divorced mother without a college degree struggling to earn a living in a low-paying office position and caring for her infant son. One night a woman was abducted from the parking lot of the townhouse where Mrs. Willard lived. “That was the final straw,” she recalls. Her parents and sister had moved to a city in the state where she now lives. She decided it was time to join them. When she got there, she hated it. “I thought I had moved to hell,” she says. “It was just hideous.” But one evening she met a man at a party for divorced adults, then fell in love with him, and got married. They lived in this city for most of the next two decades. In her late forties, she finished college and got a job as a newspaper correspondent. Life, though, remained complicated. Her father was in and out of the hospital dying of cancer. A teenage son was in rehab for addiction. Two elderly relatives were ill and required care. Then came the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001. She and her husband had often talked about moving to a small town. The attacks jolted them into doing it. The transition took four years. During that time they commuted and switched jobs several times.14

Mrs. Willard says her small town is like a “great big dysfunctional family.” The part she likes is that life is simple. “It’s like moving back to our childhood,” she says. When her children grew up and moved away, and when her parents died, she found herself “really missing family.” The town provided that. People knew and cared for one another. They also knew everyone else’s business, which was what made it seem dysfunctional. “Every day is like a great theatrical production finding out what everybody is talking about,” she explains. “If somebody gets a nosebleed, you know about it.” Those aren’t the only problems. Lots of little arguments occur among neighbors, like someone’s dog chasing someone’s cat. She also says her finances are horrible. She earns half as much as she did in the city and works just as hard. Her husband runs a small gift shop that barely covers expenses. She has to drive fifteen miles to buy fresh fruit and vegetables. Yet she doubts that she will ever leave this town. She isn’t sure she would want to. But she does have regrets. She fantasizes about traveling and living other places. “Oh God,” she says, “wouldn’t we all like to have a do over? Oh my God, it would be so wonderful!”

Another person who lives in a small town because of unexpected circumstances is Mark Ingram, a man now in his sixties. He and his wife currently live in a town of six thousand where they draw on Social Security, and he works part-time at a local accounting firm, devoting as much of his spare time as possible to charity work, such as collecting toys for children whose dads are incarcerated at a medium-security prison in a neighboring town. In college Mr. Ingram hoped to become a pilot, but on graduating he was drafted, served his time in Vietnam, and then got a job in another state at a retail store operated by a regional franchise corporation. The company moved him from state to state, and after several years he was working in a large city at the regional headquarters supervising credit and collections for three hundred thousand customers at 150 stores. Then the company went bankrupt and he lost his job.

Mr. Ingram found employment in the finance division of a large software company, lived in cities in several other states, and then became unemployed again when the company closed its finance division. After that he took a job with another regional retail franchise chain and was transferred to the small community where he and his wife now live. That company experienced such difficulties supplying items to its stores that he decided to quit. In his fifties at the time, Mr. Ingram was less employable and less willing to move. He accepted a job selling cars and then was glad to find work filling out tax reports at the accounting firm.

Despite the many setbacks he has experienced, Mr. Ingram has become philosophical about it all. When he was growing up, his dad always put him down, he says, and told him he would never accomplish anything in life. He feels he has achieved quite a lot. Although his career has been filled with unanticipated twists and turns, he decided long ago that money is not everything and he is happy to have raised three lovely children. Still, he has mixed feelings about living in a small town. He says it is nice to know everyone and not have to fight rush-hour traffic. But he mentions that the city fathers are narrow minded, and dislikes the fact that everybody knows everything about everyone.

As this story illustrates, there is a point at which people may opt to stay in their community rather than seek greener pastures elsewhere. For Mr. Ingram, it was the realization in his fifties that the chances of finding a better job in another town were slim. There are also residents in small towns who make this decision much earlier, not because they are returning to their hometown or have been unable to find work elsewhere, but instead because they have come to realize that community is essential to their well-being.

Pete Latham, a car salesperson who has just turned forty and lives in a town of ten thousand, provides an interesting example. By the time Mr. Latham went to college, his parents had lived in eight different towns in several different states. He grew up feeling he had no friends and did not fit in anywhere he lived. He says college was like going to a candy store. He hoped to become an attorney like the ones he saw on television, but drinking, using drugs, and hanging out with his new friends proved more appealing. “I really went wild,” he remarks. “I was the type of guy who would go to a bar and pick a fight just to see if I could do it.” He doubted that he would live past thirty.

After college Mr. Ingram spent four years in the navy, got a job selling computers, married a woman he met at work, and had a son. Soon after, he and his wife quit the job over a labor dispute and moved to another state, where he began managing a rental storage company. His marriage was going downhill rapidly. Separated from his wife, he and his son moved to the town where he now lives. He worked at a meatpacking plant slaughtering cattle and hogs until he decided the job was making him into a more vicious person than he wanted to be. That was when he started selling cars. The reason he did not move on was that he “hit a wall,” as he puts it. He had always felt he “wasn’t really grounded in anything.” Some friends persuaded him he needed to settle down. He had custody of his son, so began working on reviving his relationship with his estranged wife. With the help of his friends and a local church, his marriage is working again. For the first time in his life he feels grounded—in no small part because of his community.

In considering people in small towns whose lives have been interrupted, we should of course not assume that all of them have experienced downward mobility or are necessarily unhappy. Many residents of small towns are pleased to be where they are, even though life has not turned out as they expected. Especially if they grew up in low-income families, saw their parents struggling to make ends meet, and had few opportunities themselves, the hard knocks they may have experienced are all too familiar. Although they may have dreamed about a better life, they know that things could be much worse. Compared to their parents’ lives, theirs may seem reasonably comfortable. Two brief examples offer illustrations.

Thelma Thompson is in her late sixties. She is African American, divorced, and a lifelong resident of a racially mixed southern town of about five thousand. Her twelve brothers and sisters have all moved away. Most of them live in cities. She married young, devoted her time to being a mother, and then worked for years as a cook. A few years ago after several bouts in the hospital, her work became too strenuous. She now works part-time for the school district as an assistant, helping handicapped children get on and off the school bus. The median income in the community is about a quarter below the state average. Hers is less than one-third of the state average. “I’m able to manage,” she says. “It’s all in managing. I’ve learned how to budget.” Her tiny three-room house with a sagging front porch was a fixer-upper. Her son did most of the work. Her wages cover the mortgage. One of the neighbors mows the grass. She has a few flowers and tomato plants out along the curb. “I love getting out there in the yard,” she says. The slow pace of life suits her. She recalls her childhood, fetching wood for the old potbellied stove, picking cotton, walking to the fields on a hot dusty road, and being told to sit at the back of the bus. It amazes her that things have changed so much.

The second example is Doris Bunting. She also lives in a racially divided southern town, but is white. The community once had more than thirteen hundred residents, yet over the past fifty years has declined to half that number. The school closed a few years ago. So did the drugstore and grocery. The nearest doctor is twenty-five miles away. A good house can be purchased for forty thousand dollars, or less than half the state average. Mrs. Bunting got married right out of high school against her parents’ wishes, although there was little chance of her going to college anyway. Her dad held a low-paying job at the local sawmill and traveled seasonally as a construction worker. Now in her fifties, Mrs. Bunting is divorced. Early in her marriage she moved from place to place, living temporarily in five different states as her husband’s work in construction required. She tried running a gift shop for several years, but the store failed. She now works part-time at the community library. She says it is almost impossible for women to find work. Labor at the sawmill is too hard for women, and besides, the sawmill has scaled back to one shift. Some of the women used to drive thirty miles to work at a poultry-processing plant, but it shut down a few years ago. Mrs. Bunting feels fortunate. Life is much easier than it was for her parents. At least she has steady indoor work. She has a “paid for” house and two cars. Her daughter lives nearby.

These two stories capture the realities of life for low-income residents in small towns. Divorced and existing on meager wages from part-time jobs, neither woman would be able to live in more expensive housing in a city. At their age, they have few opportunities to improve their standard of living. Mrs. Bunting, for instance, says her experience as a shop owner and in dealing with people should qualify her for a better-paying job, but she would have to move, and she thinks her age would make it difficult to find employment. Despite the lack of better incomes, both women have actually experienced upward mobility compared to their parents. The fact that housing is cheap and neighbors look out for each other makes smalltown life a desirable option.

Among the people we talked to, stories like those of Thompson, Bunting, Latham, and Ingram were fairly typical of residents for whom a small town served as a refuge. It offered them an island of stability to which they could return after struggling with personal difficulties elsewhere. In that respect, the changelessness of small-town life was key. The frog pond itself was a constant.

But there were interesting exceptions in which the frog pond also changed, sometimes for the worse. I was reminded of these situations as I listened to Yolanda Jones describing how she had come to live in a nine-thousand-person industrial town seventy miles from the nearest city. She had grown up in a town of ten thousand about twenty miles from her present community. After high school she went away to college at a large state university, where she majored in business and met her future husband. They married, moved to a city of two million, and found jobs. Neither liked their jobs, though, and her husband, who had grown up in the town where they now live, was suffering from a serious case of homesickness. They quit their jobs and moved to his hometown.

It was a good decision at the time. Over the years, the town had become the regional headquarters of a large manufacturing firm. Its middle class was large for a small town because of the managers employed by the company along with the local economy’s ability to support good schools, several medical clinics, and a hospital. The community’s wageworkers mostly held decent-paying union jobs at small plants that served as suppliers of industrial motors and aircraft parts. Mrs. Jones and her husband found white-collar jobs, and considered the community an ideal place to raise children. Unlike smaller towns in the area, the community was large enough and its economy was strong enough to have attractive cultural amenities. These included its schools, a library, a citizens’ organization devoted to historical preservation, a small art gallery, and occasional concerts and plays. The town was even becoming a destination for tourists.

That all worked well for the Jones and their two children for about a decade. Then the manufacturing firm that was the mainstay of the community moved its headquarters. Within a few weeks, the managers who had made up the local gentry relocated. Simultaneously, one of the smaller manufacturing plants shut its doors and the other two cut their workforce by half. One of the nation’s largest Internet merchandizing firms seized the opportunity to set up a call center and distribution facility, hire unemployed workers part-time, and pay them minimum hourly wages with no benefits. Within a few years, the community still had the highest unemployment rate in the state and more than half the children were on subsidized school lunch programs.

Mrs. Jones was one of the fortunate few who retained her job. It is reasonably secure because she works in social services, administering programs for the elderly who no longer have money from pensions as well as the homeless who have experienced bankruptcies and foreclosures. She will stay, but the cultural amenities are gone, and the community is recasting its self-image. Her story illustrates that safe havens are not always as secure as residents might wish.

GOOD WIVES AND MOTHERS

Judging from the people we interviewed, it may be the case in some communities that women living in small towns are more likely than men to have moved there from somewhere else because of their spouse’s family or work.15 This difference is an item of comment even on blog sites by women in small towns warning other women of the dangers of being attracted to plain-spoken honest men who would lure them back to their hometowns where the unsuspecting woman would soon experience regret. The men stay local because they farm with their fathers, work at a family business, or hold jobs attained through family networks. Or they return to their hometowns because they enjoy fishing at the old pond and drinking beer at the local tavern. Their wives are women they met in college, while traveling, or during some interval working in a city. That means the wives are newcomers. Wives of men who had grown up elsewhere usually are newcomers as well. In both instances, the wives follow their husbands to a place that holds few career opportunities for women. If they are teachers or nurses, they are fortunate. Otherwise, they help contribute to the family budget by cleaning houses, waitressing, working as paraprofessionals at schools and nursing homes, or finding employment at an office or store. Pay is low, opportunities for advancement are limited, and a seemingly secure job can disappear overnight. Their satisfaction in life, they say, comes mostly from being good wives and mothers. This is not to say they are unhappy. They have nevertheless made choices or found themselves in situations that involved sacrifice.16

“Sometimes I feel like I went to college for no good reason.” This is Janice Kemeny talking. She has three children under the age of six and lives on a farm ten miles from the nearest town. The town is too small to need a stoplight. For anything besides gas and a few groceries, she has to drive fifty miles each way to a larger town. That includes trips to the pediatrician whenever one of the children is sick, regular forays to Walmart for household necessities, and frequent runs for parts and repairs when one of the farm machines breaks down. In between, she cares for the children, cleans the house, and does the laundry. During busy seasons on the farm, she drives a tractor, hauls hay, and helps her husband and the hired man keep the irrigation pumps running. Busy as her life is, she does not feel what she does is interesting or important. “It’s like you work all day, go to bed tired, and the next morning you wake up and it’s the same thing all over again. That’s how I feel. It’s sort of frustrating.”

Mrs. Kemeny did not expect to become a farm wife spending her life in the country near a small town. Growing up in a town of twenty thousand that, compared to her present location, seemed almost like a metropolis, she planned to go away to college, become a pharmacist, and live in a city. Instead, she fell in love and got married right out of high school. She and her husband, who was from another state, moved to that state and tried to find work. Barely surviving hand to mouth, they decided to move back to her hometown, where they could get help from her parents and she could take classes at the community college. Within a year her husband filed for divorce. Devastated, she made up her mind to pursue her dream of getting a college education after all, and the next year moved to a city with a large university. Still struggling with the emotional damage from her failed marriage, she did not do well. Chemistry proved so difficult that she abandoned her hope of going into pharmacy. She graduated with a degree in accounting and passed the certified public accounting exam. “I was pretty proud of myself,” she says.

Deciding what to do next was a struggle. She was dating the man who is now her husband, but she was unsure if marrying him was what she really wanted. He was farming with his dad in the middle of nowhere. She had thoughts of pursuing her career in a big city. She was good at accounting, and figured that in a city she could attain advanced certification, move up the corporate ladder, or perhaps work on a graduate degree. At least accounting was something she could also do in a smaller community. To see what might work out, she took a job in the town she now commutes fifty miles to, not in accounting, but instead doing office work for the school district. It was not what she wanted. But she did decide to go ahead and get married. Her husband was doing well enough with farming that they could get by without her income. She decided to stay at home and start having children.17

Mrs. Kemeny has been relatively fortunate because the farm has been large enough to support the family. Brenda Morawska’s story includes elements that are more typical. She went to college in her home state, earned honors, and then went off to another state, where she earned a master’s degree and became a research statistician at a research and development firm in a large city. Her husband also had a postgraduate degree and worked in the city. But he was from a farm background, and when his father died, his mother asked if he wanted to come home and farm or if she should sell the land. Mrs. Morawska and her husband moved to the town of seven thousand where her husband had been raised. The farm was too small to support them. After a professional job that her husband was counting on fell through, he wound up working as a part-time maintenance person. Mrs. Morawska worked whenever she could as a substitute teacher at the elementary school. There was “no demand for research statisticians,” she says, stating the obvious. After a few years teaching, she got a job at a sporting goods store in another town. After that, she used her knowledge of computers to manage the office for an electric contractor.

Mrs. Morawska has just turned sixty. She works as a secretary at a nonprofit organization in a town that requires her to commute fifty miles a day. Her husband commutes forty miles each way to his job. The nearest community of any size is two hours away. On the rare occasion when they go there to shop for groceries or clothing, the gasoline bill makes them wish they had stayed at home. She remembers vividly how difficult it was adjusting to the rural life. “Moving down here was just a terrible, terrible thing for me,” she says. “It was culture shock to move from the big city to a town at least a hundred miles away from anything.”

For women like this who have given up a promising career that could have been pursued more successfully elsewhere, living in a small town is at best a mixed blessing. On the one hand, they find fulfillment from being good wives and mothers, and consider themselves fortunate to live where children can play safely and have friends. Mrs. Kemeny happily uses her accounting skills to keep track of the farm’s finances. Some mornings she sits at her home computer doing tax reports for a couple of clients she knows from college. She believes in spending as much time with her children as she can, teaching them early and not expecting the schools to be their main source of learning. On the other hand, she misses the other path that she chose not to take. “When you work really hard for something and achieve it,” she says of her college degree, “it changes who you are.” She would like to go to law school if she could. “I have a lot of dreams,” she adds, “but I don’t think any of them are realistic.” Mrs. Morawska has concluded that dreaming is overrated. She advises against believing that happiness comes from achieving your dreams. “You have to have goals,” she says, “but they have to be realistic. The ability to change and adapt is just about the hugest thing anybody can have.”

Being a good wife and mother in a small town involves more than simply switching emphasis from a career that might have been fulfilling to the humdrum daily round of doctor’s visits and laundry. Women who have made that choice in small towns report the same joys and sorrows that women in cities and suburbs do. They say it is enormously rewarding to be present for a child’s first steps or first day at school, and appreciate living close to a good school and being able to help with after-school programs and committees. But they also worry about the lack of opportunities in small towns. The school may be too small to have an adequate music program. There may be no piano teacher in town. Not having grown up there, women may feel the old-timers treat them as outsiders. If they pitch in and volunteer for civic activities, they can soon be overwhelmed because they are among the few willing to do so. Meanwhile, they at least have to be creative in finding ways to pursue their goals.

A pattern of adjustment that is becoming more evident in small towns than would likely have been the case a few decades ago is maintaining a dual residence. For women with careers that require employment in cities or suburbs, but who are married to men who farm or have jobs in small towns, dual residence offers a solution. For example, Lenora Vickstrom, a married farmer we talked to in a town of nineteen hundred, told us she intends to take a job in a city when their son graduates from high school, live there during the week, and commute home on weekends. That will probably work out for her because they have only the one child and she has been able to keep active in her career by working as the chief financial officer for the local hospital. In the meantime, though, Mrs. Vickstrom has had to make a difficult transition to small-town life. She grew up living in cities and has always wanted to live in one. But one summer when she was in college, she visited her grandparents in a small town about thirty miles from where she now lives and a friend there invited her to a rodeo. At the rodeo she met her future husband. She wanted him to follow her career, but since he owned land, she followed his. Although she loves the peacefulness, safety, and simple fun of living in a small town, she still prefers the city. “When you are from the city,” she says, “you are used to diversity and many different cultures. When a city girl is placed in a small town where there is one culture, one way of doing things, it is truly hard.” It was like going back in time twenty-five years, she explains, because small-town women were expected to find their place in the home, work hard, raise a family, and keep quiet, whereas she had grown up thinking a woman should use her education to get ahead and speak up if she had an opinion. “But what do you do?” she muses. “You choose your life and you make the best of it.”

One of the most remarkable stories of adjustment we encountered was that of Rosemary Case, a mother of four who lives in a town of eleven hundred located more than two hundred miles from any major city and more than a thousand miles from the city in which she was raised. As a girl growing up in a middle-class family with well-educated parents who earned a good living in the professions, she dreamed of being a ballerina and somehow combining that with her interests in writing. After high school, she went to college intending to further her interests in writing by majoring in English and taking psychology classes as a form of self-exploration. That spring her world was shaken by the killing of four students at Kent State University in Ohio. The hippie lifestyle of the campus counterculture beckoned her to embark on a cross-country journey of further self-exploration. Somewhere along the way she met a man who said he loved her. He was fresh out of the navy and had no money, but figured he could earn a living in construction. They settled in the small town where her husband had been raised. The rent on their little house was thirty dollars a month. They heated it with wood. Soon their first child was born. Her husband’s family helped him find jobs and assisted her with babysitting. Money was so tight she needed to work. The only work she could find was cleaning motel rooms. She applied for a job at the local newspaper and was turned down. There was no way she could continue going to college.

“It broke my heart,” Mrs. Case recalls about being turned down for the newspaper job. “It was just devastating. My self-esteem just crashed.” But a year later, the man who ran the newspaper died and his widow was struggling to keep the paper in business. The woman hired Mrs. Case as her assistant. It was part-time work and did not pay much, but it was something. It fit well with having children, helping them with homework, and having time to be involved in their after-school activities. Over the years she became a Cub Scout den mother, served on school committees, organized a Students against Destructive Decisions chapter in the high school, and was active in one of the local churches. She remains an oddity in the town, as a woman who still cherishes the freedom of the hippie culture, thinks it would be nice to live in a commune, and dreams of writing a book someday. But she has become a firm believer in the value of living in a small town. She would never move back to the city where she grew up and hopes her children won’t either. The problem with cities, she says, is that “everything is transient.” She thinks it is unnatural and unhealthy for families to migrate so much. “What we have here,” she explains, “is the generations. I think that is what God intended—families should stay close.”

For women without college educations, the disappointment of not being able to pursue a career in a small town may be less, but their lack of education further restricts their opportunities. An example is Calida Rawlins, a woman we met in a town of about a thousand who is in her early sixties yet still spends most days cleaning motel rooms. She grew up in a city, recalls having few aspirations in high school other than becoming a wife and mother as well as perhaps working as a secretary, and got married soon after she graduated. Her husband’s life had been disrupted when he was drafted to fight in Vietnam, and he wanted nothing more than to return to his hometown. They did. His parents owned a motel, and the newlyweds settled into being assistant motel managers. “It took me awhile to work my way into the community,” she recalls, “because I thought very differently than most of the people here.” After her children were in school, Mrs. Rawlins took a job at a local preschool program. The motel business was hardly thriving, located as it was in one of the poorest counties in the state, and she and her husband were having trouble paying their bills. She enjoyed working with the preschoolers. That job continued for twenty-three years. But then preschools came under state certification requirements, and with no education, she lost her job. She has been back at the motel ever since. Each morning she tallies the income and expenses, fills out government reports, and then goes from room to room with her cleaning cart. She seldom gets out of town. “The motel business,” she says, “was not my choice. It was my husband’s choice.” She adds, “Business doesn’t float my boat.”

In cities and small towns alike, women’s lives are shaped not only by their husbands and children but also by the needs of their parents. One case of this is Georgene Partridge, a woman we talked to who lives with her husband in a comfortable brick house in a town of about twenty thousand people. Mrs. Partridge has a college degree and expected to use her education as a teacher, but she has never held a position in teaching. The closest she has come is teaching Sunday school and helping her children with their homework. At first she stayed home because she wanted to focus as much of her time as possible on her children. Her husband felt the same way, and switched his job as an accountant to a small firm that offered nine-to-five hours and no work on weekends. But by the time their children were old enough to be on their own, Mrs. Partridge’s mother died and her father needed her help, so they stayed in the community for that reason, and she did not teach. Then her husband’s mother died, and she helped care for his father as well. She has no regrets, but her life did not turn out exactly as she expected it would.

Mrs. Partridge’s experience is a story that happens in communities of all sizes, and affects lower-income families more than ones whose parents can afford retirement homes and assisted living facilities. What is perhaps distinctive about the people we talked to in small towns is that their sense of obligation to their parents was strong enough to keep them in the community to help their parents even when they could have afforded other arrangements. In many instances, the people who stayed had siblings who had moved away. The ones who remained said they liked small-town life, but they also were especially convinced that someone needed to be close to their parents.18

Although it is most common for women in small towns who have moved there because of husbands or parents to say they have sacrificed careers, the other issue women in this situation sometimes face is dealing with unpleasant relationships among neighbors and with in-laws. This is the more general problem that people in small towns refer to when complaining about everyone knowing everyone else’s business. If they were in a larger community, it would be easier to escape, but here it is impossible.

Marcy Prescott is a case in point. She is a mother in her early thirties who lives in a town of twenty-three hundred. Although her story is largely upbeat, her voice falters on several occasions as she describes her life, and it is clear that one issue in particular troubles her deeply. Having grown up in a city and gone to college, she expected to spend her life in a large metropolitan area, perhaps working as a teacher, married to someone from an urban background, and living close to her friends. But after college, she was surprised to find herself falling in love with a man from a small town, and he insisted on living there when they got married. Mrs. Prescott has been able to teach school there and likes the town as a place to raise children. The problem is that she has had a falling out with her husband’s sister, who also lives in the town, and whose circle of acquaintances necessarily overlaps to a considerable degree with hers. “Living in a small community,” Mrs. Prescott says, “everybody’s very aware of everything. In a city, if your sister-in-law doesn’t agree with what you do, it doesn’t have a big effect. Nobody knows and nobody cares.” Here in such a small town, though, it matters a great deal. She has tried and tried to build a better relationship, but nothing has worked. She has begun to give up hope of reconciling with her sister-in-law. “I think that would really change the chemistry in our family,” she sighs. “It just makes me sad.”

FARMING’S LEGACY

As early as the 1930s, policymakers and agricultural economists expressed concern about the rate at which children from farm backgrounds were leaving farms for better jobs in cities. It seemed clear that mechanization was reducing the need for farm labor. During the Depression, sagging crop yields and prices further reduced the chances of young people being able to stay on farms. And yet well into the post–World War II era, when many young people did in fact pursue different careers, farm life seemed to be a deterrent to higher aspirations.19 The question was why. Was it because people loved the family farm that much? Was it that they lacked skills or were afraid of living in larger places?

Some insight comes from the career trajectories of people who had been raised on farms in the 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s. The career paths range from easy transitions to college and urban jobs in the professions to much-slower and more arduous shifts out of farming. For people in this second category, a visceral attachment to land that had been in the family for several generations is often evident. But the clearest conclusion has to do with the family social ties that farming entailed. The farm was a family business as well as a place to live. For marginal farmers, it was a business that was not fully self-sustaining. In that respect it was like a small business in town, such as a grocery or hardware store. Marginal farmers kept the business going by working part-time at jobs in town that provided a steady income. Young people, usually boys, filled in for their fathers by doing chores and field work before as well as after school and on weekends. The transition from doing that to a full-time career elsewhere was frequently slow and uncertain. The uncertainty was driven by fluctuating farm incomes, indecision about whether a new career could be combined with part-time farmwork in conjunction with one’s parents, and by the health and longevity of parents. Younger people who stayed in rural communities or returned to them did so partly to sustain the family farm, but also because of needing to be near a parent with failing health or who was widowed.20

A transition of this kind is well illustrated by Leon DeSoto, a man who grew up in a town of two thousand in the 1950s. The town had been settled by French Canadians, many of whom still spoke French and had large families, which Mr. DeSoto looks back on fondly because he always had plenty of playmates in the neighborhood. His grandfather had run a bulk fuel delivery service along with a store that collected cream and eggs from farmers. His father farmed. In high school, Mr. DeSoto helped his father on the farm before and after school as well as during the summer. After college Mr. DeSoto returned to his hometown, got a job selling cars, and continued helping with the farmwork. Those years were difficult because he would work full-time in town and then work in the fields until nine or ten at night. For a while it looked like the farm income might improve, but increasingly the reason Mr. DeSoto stayed was that his father was in poor health. By the time his father died, Mr. DeSoto had worked in several different jobs in town and his children were going to college. His wife had been teaching most of the time to supplement the family income. With his father gone and no children in the area, the DeSotos finally moved away. They relocated to be closer to their children. Mrs. DeSoto teaches school, and Mr. DeSoto works in a car dealership. They still live in a small town, preferring it because housing is dirt cheap. It took them thirty years to fully sever their ties to the family farm. Their children all have professional jobs in cities.

The transition the DeSotos made from farming took a long time, but they were fortunate enough to have been to college, and find employment in teaching and sales. For others the transition has been more difficult. I introduced Mr. Dallek in chapter 2. He is the eighty-seven-year-old man who grew up on a farm, worked as a farm laborer, ran a hardware store, and then earned a modest living in a metal-fabricating plant. The farmer he worked for after he returned from the Korean War was his father. Mr. Dallek says he would have loved to spend his life farming. He stuck it out for a decade. But his father always treated him as a hired hand and refused to let him make any of the decisions about how to manage the farm. That was the main reason Mr. Dallek left farming and tried to run a hardware store, despite not knowing much about the business. He says what he has enjoyed most about the small town he lives in now, and even about the manufacturing company he worked for, is that people know him and treat him with respect. “That’s really nice,” he says, “when you’ve grown up with a father who never complimented you for anything.”

With so few of the US labor force still employed in agriculture, it is easy to conclude that farming no longer matters much, even in small rural communities. Most of the people who live in these towns work at other jobs. But farming continues to play an important role in many of these communities. Its direct role is in shaping the local economy. In good years, townspeople do well because crops and livestock are the main items that bring outside revenue into their communities. In times of crisis due to weather or weak agricultural prices, businesses in town suffer. These effects occur through the market transactions in which local farmers engage, but also because of the fact that townspeople may hold part interest in local farms, especially when landownership and farm management are shared among extended families.21

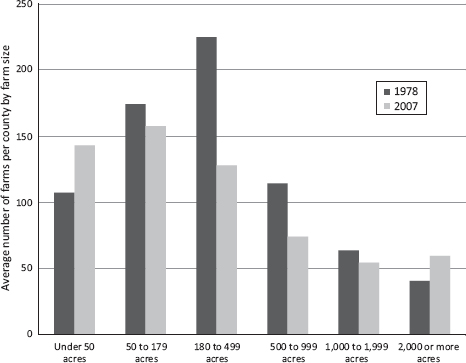

Figure 5.2 provides an overview of the ups and downs that farming communities have experienced in recent decades. The data are from annual information compiled by the US Bureau of Economic Analysis at the county level. In order to specify the information for towns most likely to be affected by farming, the 20 percent of counties for which the overall income was most dependent on the value of sales from crops and livestock in the late 1960s were selected. Farm income refers to the mean net income received per farm proprietor, and is shown here adjusted first for inflation using the Consumer Price Index and then computed as variation from the mean value across all years. The category “farmers” refers to the mean number of farm proprietors in these counties per year and computed as the ratio of that number in each year to the mean value across all years. As variation from the mean across all years, the two indexes thus appear on the same scale.22

Figure 5.2 Farmers and farm income

The most noticeable aspect of the data is the degree of annual fluctuation in net farm income. Unlike salaries in the professions and among skilled hourly wageworkers, annual incomes for farmers are highly unpredictable. They vary not only because of local weather conditions that affect crop yields but also because of global markets and the effect on those of weather in other countries. For example, the sharp rise in net farm income in the United States in 1973 was largely a function of a spike in the prices of agricultural commodities, which was in turn driven by a steep decline the previous year in grain production in Russia.23 Other factors, such as the rising demand for corn used in ethanol production in recent years, have also affected farm income, but have not overcome annual fluctuations. The farm income data also reveal that when adjusted for inflation, the amount received per farm proprietor has not risen except for the increases evident in several of the years after 2003.