7

The Fine Art of Dealing With Photo Buyers

GETTING TO KNOW THEM

Thousands of photo buyers exist in market areas ranging from the commercial (advertising, public relations firms, corporations and so on) to the editorial (books, magazines and publishing houses). In this book when I refer to photo buyers, I will be referring almost exclusively to those (mainly editorial) photo buyers who deal with the stock photographer and not those (mainly commercial) photo buyers who deal with the service photographer.

Art director, photo buyer, picture editor, designer, photo researcher, graphics director, photo acquisition director and photo editor are just a few of the titles bestowed on photo buyers at publishing houses and magazines. In this book I refer most often to photo buyers. They usually work out of an office, are between twenty-five and forty-five years old, and approve between $2,000 and $20,000 a month in photo purchases; probably half are female, and all are busy people.

You’ll find that photo buyers are interested in photographs, not photography. You’ll find, too, that setting up business with a photo buyer is quite easy. It takes just a handshake—in a letter (e-mail or postal), over the phone or in person. You’ll seldom find the contracts or lengthy legal documents (unless you request them) that you often encounter in commercial stock photography.

Photo buyers tend to mellow with age. Younger editors, new to the job, sometimes exercise their newfound decision-making power by exhibiting impatience or intolerance. Handle them with care.

Veteran photo buyers usually have survived the rigors of the publishing world with enough aplomb to be able to take the time to admire a photograph now and then. They’ve also honed their viewing skills to the point where they can speedily select the image they need out of a large pile as if by magic. This brings to mind: Always send a photo buyer more pictures than you believe to be adequate, provided the pictures are appropriate. You’ll often be surprised at the pictures the editor chooses. Don’t edit your selection (except to delete off-target pictures). Let the editor do the editing. Beware, though, that some buyers want only exactly what they have requested.

A visit to a photo buyer’s office will bring home to you my adage about picture editors buying pictures they need, not pictures they like. The walls of an editor’s office are plastered with lovely Track A pictures: prints clipped from calendars or signed originals from friends. Track B pictures, the kind the editor authorizes a check for, are rarely on the wall. What editors need and what they like are different. Marketing is understanding that difference.

Your pictures may have won contests or received awards, but the real judge of a marketable picture is the photo buyer who signs the checks.

The Reliability Factor

Always remember that it can take months to build a good reputation for yourself but only seconds to destroy it.

One paradox in the story of creativity in the commercial world is that those who succeed are not necessarily the most talented. In all creative fields—theater, music, art, dance—talented people abound. However, the world of commerce is a machine, and a machine operates well only if all parts are moving smoothly together.

The people who sign the checks will readily admit that talent doesn’t head the list when it comes to selecting a new person for a part, an assignment, or a position. History has taught them that “the show must go on,” that reliable people make commercial productions a reality. Someone with passable talent who is dependable will probably be selected before the unpredictable genius.

Thus, an unwritten law in the world of commercial creativity is the reliability factor. How well would you stack up if a photo buyer were to ask, “Are you available when I want to contact you? Are you honest? Prompt? Fair? Dependable? Neat? Accurate? Courteous? Experienced? Sharp? Articulate? Talented?”

I placed Talented at the bottom of the list because that’s where most photo buyers will place it. They assume you are talented. Their basic question is, “Can you deliver the goods when I need them?”

Because you’re talented in photography, you purchased this book. You know your work can easily compete with the pictures you’ve seen published, but talent will not be your key to success in marketing pictures. You will succeed in direct proportion to the attention you pay to developing and strengthening your reliability factor.

There are exceptions to everything, of course. Even with a low reliability factor, some creative people succeed. (Witness the temperamental screen idol or the eccentric painter.) Usually, though, they are coasting on previously established fame, or they exhibit a unique ability. As a newcomer to the field of photomarketing, your greatest asset will be your ability to establish a solid reliability factor with the markets (photo editors) you begin to deal with.

The Photo Buyer Connection

You will connect with photo buyers in person, by phone, by fax, by e-mail and in writing. As an editorial stock photographer who conducts business via e-mail and the mailbox, it’s important to express yourself well in your communications with photo buyers.

From my ongoing overview of photographer/photo buyer relations I have noted that if a breakdown occurs, it’s usually because the photographer didn’t express himself clearly, whether in text, in person or by phone.

Many photo buyers reached their picture-editor post after serving as a text editor—and many continue to do both. They’re often journalism or English majors initially attracted to editing and writing because of their communication skills.

In dealing with photo buyers, if you experience a misunderstanding or mix-up in regard to purchase, payment, assignment or whatever, here’s how to handle it.

- Give the photo buyer the benefit of the doubt. Despite the harangues we hear from some of our fellow photographers, rarely will you encounter an intentional hustle on the part of a photo buyer. If you’re in a dispute with a photo buyer and you’re positive the fault is his, rest assured that it was probably an honest mistake. We’re all allowed some of those.

- Be firm but not offensive. Consider the buyer’s self-esteem, too.

- If you’re emotionally upset over a transaction between yourself and a photo buyer, wait a day (twenty-four hours) before you react.

- Photo buyers are continually up against deadlines and will be short with you. Some will offer you a fuse to ignite; don’t be tempted.

Remember this: The photo buyer is dealing with you probably because she considers your work valuable, even essential. Don’t let a harsh word or irresponsible statement slip out and get in the way of future opportunities to publish your work (and deposit checks).

The newcomer to the field of photomarketing often is amazed, and sometimes insulted, by the casual approach many photo buyers take in their handling of photographers and the photographers’ work. To a photographer, a photograph can be like a child, an extension of the soul, a piece of poetry or music. Photo buyers don’t have the same reverence for your work that you do; they can’t. You may consider your photograph a work of art; to them it’s another piece of work to process. This is not to say they don’t admire talent or good photography. They do—most of them. However, to survive in their field, they have to learn to separate their emotional appreciation from their career demands.

If you take the same approach with your stock photography—that is, separate and compartmentalize your photography into marketable pictures that will feed your family and not-so-marketable pictures that will feed your soul—you will be able to suffer the jolts and inconveniences of photo buyers without feeling they are callous or insensitive. They usually aren’t. They’re just doing a job, and they’re usually doing it well.

Should You Visit a Photo Buyer?

I recommend against it for the same reasons I don’t think calling a photo buyer is a good idea, but if you’re dead set on visiting, keep on reading. If you tailor your marketing plan correctly, your specialized markets will be scattered throughout the nation, even the world. Unlike the service photographer who can work effectively with commercial accounts within the confines of a single city, the editorial stock photographer deals with far-flung buyers—mostly through the postal mail (see chapter nine) and e-mail.

I have dealt with some photo buyers for a decade and have never met them. My reliability factor continues to score high with them. A personal visit would serve only to satisfy our mutual curiosity.

Yet while personal visits are not always necessary, they can be a real plus. Personal visits, if conducted smoothly, always help seal a relationship. If my itinerary and schedule permit, I drop in on photo buyers when I can, to say a personal hello. People do respond more actively to a face than to a letterhead. If you’re trying to develop a new market, a personal visit to a key buyer could be your turning point. Or a personal visit might help solidify your relationship with an editor you’ve already been dealing with successfully. However, you will not necessarily find photo buyers eager to set up an appointment with you, especially if they don’t know you. Talent is plentiful. Besides, they have deadlines coming up tomorrow. If they need photographers, they’ll consult their photographer files. They know that personal visits take time and aren’t often immediately fruitful. Their needs are too specific for a general introductory visit to solve.

Don’t make an appointment unless (1) you have sold a picture to the photo buyer in the past couple of years, or (2) you have something of value to give the photo buyer, such as information or photos targeted to what you have learned is a current need for him. Photo buyers are understaffed and underpaid. They’ll have little reason to welcome an “I’m me and I have photos” visit from you. You’ll end up creating a reaction opposite to what you’re after and getting put on that buyer’s blacklist. If you can make your visit worthwhile to the photo buyer, however, you’ll be greeted warmly and your time will be well spent.

Realistically, a visit to a photo buyer can be extremely costly for you. In effect you are making a sales call, and in the corporate world, a salesperson’s call costs just about the price of the suit he is wearing. As of this writing, the average cost of a sales visit is $557. Remember that first impressions are enormously important and if you decide to visit you really need to spend some money on looking sharp. Does this mean you have to wear a suit? I don’t think so. Clean jeans, a turtle neck or shirt and tie and a jacket is perfectly acceptable most of the time. But if you are visiting a photo buyer for the first time, how do you know what is acceptable at that particular publishing house? Yet another reason not to visit a photo buyer in person.

PHOTO BUYER REQUIREMENTS IN THE DIGITAL AGE

Exact requirements for final digital submissions vary from photo buyer to photo buyer. But generally speaking there are two basic things you need to keep track of.

Low-res submissions are typically anywhere from 500 to 1,000 pixels on the long side at a resolution of 72 dpi. Photo buyers use these low-resolution submissions to preview photos before purchasing. I’ve always felt it better to err on the side of slightly too large with these submissions just to give the photo buyer more room if needed.

High-res submissions are typically files as large as your camera puts out (you should be shooting in RAW or similar and then developing the digital files) saved as TIFFs or JPGs at 300 dpi at around 12" (30cm) and up on the long side.

When we do the photo buyer survey report we are in contact with a large number of photo buyers and speak to them about a wide variety of things. One topic that always comes up is as follows: What are some of the most commonly made mistakes photographers do when dealing with you? Here are some random answers.

“Sending low-res previews that are either too small or have a huge watermark obscuring so much of the photo that I can’t see the photo clearly. These immediately get deleted…”

“I prefer to work with photographers that can set up a digital lightbox on their own website to show me their work. If I absolutely have to I’ll work with low-res previews through e-mail, but lightbox is by far my preferred method…”

“An amazing number of photographers do not view our submission guidelines before sending in their work. If they did, it would save them—and me—a lot of headaches. All the details on how we want submissions sent to us are right there in the submission guidelines. To me, a photographer that can’t take the five minutes it takes to read through our submission guidelines prior to submitting is very likely not a person I would want to work with anyway.”

“Even though we stopped accepting slides almost ten years ago I still get sample submissions consisting of slides at least once a month. These are returned to the photographer immediately as for liability reasons we don’t even want to touch those submissions these days. It’s digital or nothing with us I’m afraid…”

“Photographers need to do their homework before submitting images. We’re a small regional New England magazine covering our local area. No matter how nice, I have no need for photos of tropical beaches or travel photographs from Paris, France.”

It can seem like a lot of extra work to really tailor your initial submission to a magazine to exactly what they want rather than have some general mailer that covers everything. But if you do, it shows me two things. One, you pay attention to detail. Two, you’re willing to work a little bit to meet my needs and that is huge to me. I was a photographer before I became an editor and I still remember using Photographer’s Market as my required reading before sending an initial submission to anyone. Photographer’s Market has done a lot of the hard work for the photographers. Use that excellent resource for the first go-through and then check the website of the publisher to see if there are any more detailed submission guidelines. If possible, pick up a copy or two of the magazine and really tailor your submissions. Your hard work will be rewarded.

If you live close to some markets, those visits need not cost that much. For your far-flung markets, though, the cost could be much more.

By working smart, you can cut such costs by diverting funds that would be spent for personal visits toward contacting buyers by e-mail or postal mail instead. Since photo buyers buy pictures not because they like them but because they need them, your tailored selection of twenty-five to a hundred images on a CD, or your tailored sales sheet mailed to a buyer, will serve the same purpose as a personal visit with your portfolio. Also, your selection will receive more attention from the photo buyer. Remember, as an editorial stock photographer, your separate photo buyers will not require you to be versatile; therefore, a portfolio that demonstrates your wide range of photographic abilities will not be necessary.

Should You Write?

Postal mail is an effective way to contact and deal with photo editors. Chapter nine shows you how to write the standard cover letter (Figure 9-1) and how to graduate to the “magic” query letter (Figure 9-2) that captures a buyer’s interest every time. You’ll also learn that looking like a professional is key to the success of any correspondence you have with a photo editor.

Letter writing is probably the least expensive method of contacting photo editors, besides e-mail (but e-mail has its own inherent problems—how do you like all that unsolicited e-mail you receive every day?). Nevertheless, the corporate world tells us that letter writing is not cheap: Each business letter costs about the price of breakfast at a restaurant. As of this writing, the average cost is $9.75. The stock photographer’s letter can be much less expensive, as I’ll show in chapter nine. Because you have narrowed your list to a select group of markets, you’ll find that you’ll need only about a dozen basic letters.

By using the mail to contact photo buyers, you’ll have the opportunity to include self-promotional literature (“sell sheets”) that will serve as an effective reminder to your clients that you exist and that you can produce what the photo editor needs.

One excellent way of writing photo buyers is to use postcards. If you have your own postcards printed, you can display one—or more—of your images when writing a prospective client. Vistaprint at www.vistaprint.com and Modern Postcard at www.modernpostcard.com are two postcard printers that come highly recommended.

Should You Telephone?

Phoning can be a bit of a gamble and should be avoided unless absolutely necessary. The reason for this is simple. When you send a photo buyer a postcard or an e-mail, the photo buyer can read it and see it when time permits. A phone call has to be dealt with then and there, which might be an interruption for the photo buyer.

Above all, do not use the phone to find out basic information. If you need to find out the name of a photo buyer, check out the organization’s website, or ask the receptionist answering the phone.

If you need to call the photo buyer, here’s the secret: Before you make the call, study the buyer’s needs backward and forward, get the company’s editorial calendar (of upcoming features), and then make up a give list. Decide what you will give the photo buyer.

How do her needs match your PS/A (your Photographic Strength/Areas)? You won’t be wasting her time when you can say, “I’m a bass fisherman, and I have some excellent pictures of bass fishing in Florida, which I understand you’ll be covering in your magazine next August.”

Once you’ve established contact with a photo buyer and perhaps sold a photograph or two to him, the following kind of call could be appropriate: “I regularly vacation in Maine, and I’d be available for assignment when you need to update your files of New England pictures.”

This call is better avoided: “I notice you have continuing need for classroom pictures. My neighbor is a teacher. With a few guidelines from you, I could get the kind of pictures you want.”

Instead, check the photo buyer’s website for submission guidelines. If there are no guidelines on the website, write the photo buyer asking for a copy of the guidelines and enclose an SASE (self-addressed, stamped envelope).

Generally, if the information you want the photo buyer to have can be communicated on a postcard, in a letter or by e-mail, pick that option instead of calling.

Should You E-Mail?

You bet. However, there are a few things to keep in mind.

- E-mails to info@, sales@ and similar general addresses are seldom successful unless you’re requesting very general information. Often these are auto-response mailboxes and will send you only a boilerplate response. Find out the name and the e-mail address of the person you need to get through to.

- Spend some time browsing the publisher’s website before you e-mail a question. Sometimes the answer is readily available on the company’s website.

- Spam is the word used to describe inappropriate, unsolicited junk e-mail. If you have the need to send a large number of e-mails to photo buyers, always see to it that the option of being taken off your e-mail list is included in the missive.

- Unless you’re on a first-name basis with the photo buyer, avoid irony, sarcasm and other things that could be misunderstood. In addition, rarely rely on the smiley face, :), to cover a dubious statement.

- You’ve probably received e-mails sprinkled with misspellings, poor phrasing and “cute” emoticons like :-), or Internet abbreviations such as *lol*, IOW, rotfl, shortened or misspelled words and so on. They didn’t make a favorable impression, did they? Although this style might be acceptable to friends and family, it won’t go over well with business associates.

- Be persistent, but also be patient. If you plan to follow up with a prospective photo buyer, allow enough time for your e-mail to arrive and be read. Then consider a courteous follow-up phone call.

- Attachments. Unless you’ve had ongoing correspondence with a photo buyer, it’s not a good idea to send unsolicited attachments. With the proliferation of e-mail viruses, some companies have a policy of refusing e-mail containing any form of attachment. This refusal is often handled automatically by their e-mail gateway software before the message is passed to the intended recipient. You can work around this problem by uploading photos or text to your Web page and giving the URL address to your correspondent.

- Cute jokes, chain letters, urban legends, hoaxes and computer virus warnings that you’ve received from others don’t have a place in your business correspondence.

Get On the Available-Photographers List

Your Track B list probably features several strong areas of special interest, ranging from gardening to sailing. You have contacted a number of potential photo buyers in each of these areas, all of whom would like to know more about you because your photographic interests match their needs. They each maintain an available-photographers list in the office. If your reliability factor looks high, you could be on several dozen photo buyers’ lists. Here’s how you get on a list:

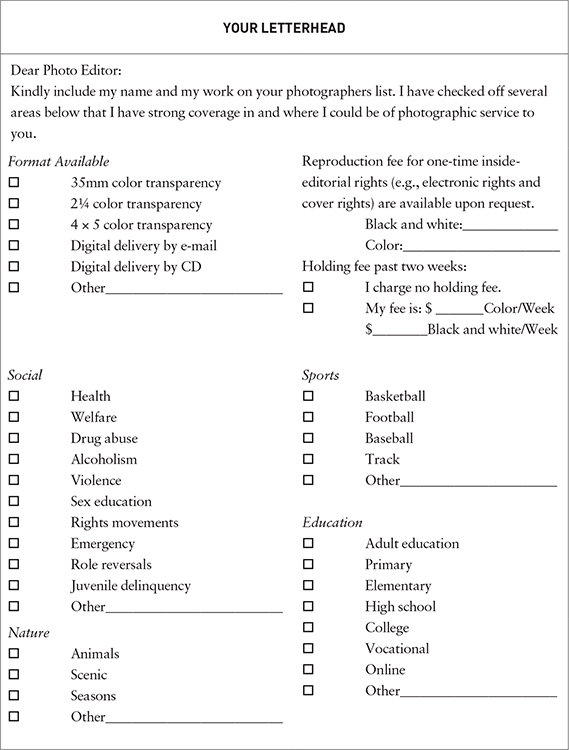

Make a categories form letter similar to the one in Figure 7-1, and send it to photo buyers in your target market areas. Don’t give in to the tendency to print only the few categories that match your Track B chart. Instead, write them all down, but check off only the ones that apply to your PS/A and the photo buyer’s needs. This may be only five or six checkmarks. Photo editors will gravitate to their own immediate spheres of interest, and when they find those specific areas checked off, they’ll take notice of you. Since you checked few other areas, they’ll know you aren’t dissipating your photographic talents over territory that is of little concern to them, and concomitantly that you must have a lot of material in the areas you concentrate on, i.e., what they specialize in. This is one of the reasons I suggest you curb your picture-taking in Track A areas and accelerate your Track B areas (see chapter three). This form letter is another way of saying to photo buyers, “I’m the person for the job.” The photo buyer will respond, “This photographer speaks my language.”

The categories letter is appealing to photo buyers because it doesn’t call for any action on their part. They can just file it for future needs. Moreover, it is concise and to the point.

Photo buyers will do one of four things when they receive your letter:

- Throw it away.

- File it to have on hand for reference.

- Phone you because of an immediate photo need.

- Put you on their available-photographers list.

Note: To repeat, resist the urge to appear versatile by checking off several categories. Photo buyers prefer dealing with specialists in their areas. If you do check off plenty of squares, they’ll say, “No one is that good!” and they’ll choose the photographers who definitely appear to have large stock files in their areas of interest.

Figure 7-1. Tailor this sample marketing categories form letter to the photo editor you are contacting. If you are a specialist, you’ll find that the photo buyer will take an interest in you. Generalists who have not mastered at least one of the categories listed are of little interest to the buyer. Don’t be tempted to check off dozens of categories.

The available-photographers list in the photo editor’s office can take many forms: 3"× 5" (8cm × 13cm) file cards, a three-ring notebook, separate files or a computerized database. Photo editors will add notes to your file, such as what they perceive to be your strong areas within their categories of interest. They may also add notes concerning conversations with you, assignments and a running list of your pictures they have used to date or pictures they have scanned to include in their central art file for possible future use.

Once you’re on the buyer’s available-photographers list, you will periodically be sent a “needs” or a “want” sheet, which delineates the current photo needs of that publishing house or magazine. Send pictures in for consideration whenever you receive a needs sheet. Depending on the arrangements you have with the photo buyer, you can submit either original transparencies or digital preview scans. Since the sheet describes the exact photos needed, you’ll find yourself saving time and postage and earning points by not sending inappropriate pictures for consideration. The photo buyer will welcome your pictures because they are tailored to the publication’s needs.

Since the publishing industry is forever in a state of change, mail or e-mail your categories form letter to each entry on your Market List at least once a year. Why? Because some things might change: (1) your priorities, (2) the photo buyer’s priorities, (3) your address, (4) your website, (5) your stationery, (6) the photo editor’s address, (7) the photo editor.

Whether or not any changes have occurred, this letter is a good reminder to the photo editor. New competition appears on the scene every day. Your letter will keep you and your work in the front of the photo editor’s mind.

Selling the Same Photo to Multiple Buyers

Multiple submission is the phrase often used when photographers submit the same photographs to different publishers at the same time. Unethical? Not at all. The reason? You’re submitting your Track B pictures to specialized markets targeted to different segments of the reading (viewing) public. There is no cross-readership conflict, especially if your markets are regional or local. In other words, the readers of magazine X never read magazine Y or Z. Feed those statistics into the ten thousand photo-buying markets that exist, and you can see why an editor is not too concerned if your photo has already appeared, or will appear, in magazine X.

What’s the appeal of multiple submissions to photo buyers? Savings. Most editors don’t have the budget to demand more than one-time rights. They know they can get a picture much cheaper if they rent (lease) the picture from a photographer on a one-time basis.

The multiple-sales system also is healthy for you, the stock photographer. It will encourage you to research more picture-taking possibilities, as well as produce more photographs because you will be getting more mileage out of each photo through multiple sales.

Multiple submission, of course, does not always apply to major national publications, such as People or Ladies’ Home Journal, who would prefer that you sell them first rights to your picture. Nor does it apply to commercial stock-photographer accounts where you often sign a work-for-hire agreement in which you transfer all your picture rights to your client. (This is a procedure I do not recommend to the editorial stock photographer—more about work for hire in chapter fifteen.)

However, you’ll find that you can use the multiple-submission system with 95 percent of the photo editors you deal with. The exceptions will be, as mentioned, large-circulation newsstand magazines, most calendar and greeting card companies, ad agencies, public relations agencies (service photographer areas) and other commercial firms that require, because of their nature, an exclusive right to, or sometimes ownership of, your photograph. (Unless a photo buyer offers you a fee you can’t refuse, don’t sell anything but one-time rights.)

Many of my pictures have been worth more than $1,000 in total sales. With one picture, for example, an art director wanted to pay me $500 for all rights to the image. That picture has earned $9,000 so far. If I had sold it for $500, I would be out nearly $8,000! The cash register keeps ringing. I’ll also be able to pass the rights to the photo on to my heirs.

Scanning and Photocopying Your Photographs

A great boon to stock photographers has been the practice, on the part of photo buyers, of scanning or photocopying certain pictures (black and white or transparencies) when you send them in for consideration. The advantages:

- Although photo buyers may not be able to immediately use a picture you have submitted, they might anticipate its future use. A copy in their central art file will serve as your calling card. When the need arises for your picture, the photo buyer contacts you for the original.

- Some buyers might hold copies of twenty to thirty of your photos in their central art libraries. Often as many as ten to forty other photo editors at the publishing house can have the opportunity to view the pictures.

- Since your original is returned to you, you can send it elsewhere. Conceivably, photocopies or digital scans of the same picture can be working for you in a couple dozen central art libraries at the same time.

- You incur no costs.

And the disadvantages? Unauthorized use of your photocopies for display layouts might occur. Copyright infringement? There isn’t any. The photo buyers are using your picture for the purpose of research [Sections 113(c) and 107 of the Copyright Act (enacted 1978)]. They are required neither to ask your permission nor to compensate you for its temporary use. However, that’s a small price to pay (and it happens only rarely) for the marketing potential your pictures enjoy while on file.

Digitizing of black-and-white and color photos is now refined to the point where it’s difficult to tell the difference between your original picture and the resulting copy. Is this a disadvantage?

Not really. Photo buyers will sometimes make digital copies—more often than not low-resolution scans—of some of your images to keep on file. Should you allow photo buyers to do this?

Absolutely.

Does the possibility exist that one of your images might be used without your permission? Yes, it does, but it would be very rare.

In the last century, with the introduction of scanning and digital storing devices, photographers feared that publishing house art directors would capture a photographer’s photos into the company’s database. They would then use the photos without paying or crediting the photographer. Except in a few rare cases where misunderstandings were to blame, this has not happened in the editorial stock photography field.

The Central Art File

Publishing houses usually start from a modest venture and then expand, sometimes over several generations. The main theme of the publisher usually remains the same. For example, automotive publishers expand with things automotive, and so on.

Large houses have large photography budgets; $40,000–50,000 per month is not uncommon for a large publishing house. If you’ve done your research well, part of that budget can be yours because you can supply pictures that fill their needs.

As you research market possibilities geared to your Photographic Strength/Areas (PS/A), you’ll plug into some large publishing houses with twenty to thirty or more editors, for as many periodicals and/or book specialties within the same firm. In marketing your pictures to such houses, you can save yourself time and expense if you send only one CD or one shipment of one set of prints or slides, rather than thirty sets to thirty separate photo buyers.

In most magazine or book publishing houses, you’ll find a central art library (sometimes called the photo library or the photo file, and sometimes referred to as “the morgue”). Depending on the structure of the library, it will accept photos in various forms: originals, dupes, photocopies and digital images. Incoming pictures are logged by a librarian and then distributed to the appropriate photo editors (or art editors or designers) for viewing. If your picture(s) is selected, the art librarian will make a delivery arrangement, put a purchase order into motion and, within a month or so, you will receive a check.

Original color transparencies are returned to you, but once your black-and-white or color print is used, it’s tagged and placed in the central library’s filing system, usually by subject, age bracket or activity. Digital images are cross-referenced by author and subject matter and stored in a database.

“But isn’t a used picture less salable?” you might ask. On the contrary. The fact that your picture sold once puts a stamp of approval on it. The next photo buyer who comes along and sees your picture in the file and notes its previous use will more likely want to use it since it has received prior approval from a colleague.

You’ll receive, generally, 75 percent of your original fee when your picture is used again. However, if the repeat sale is for other than inside-editorial use, you should receive a higher fee (see Tables 8-2 on page 117 and 8-3 on page 123).

About once a year, the art librarian will conduct a spring-cleaning of the central art file and return outdated photos to photographers.

The Permanent File System

Large publishing houses, especially the denominational houses that employ thirty or more editors, are always in need of up-to-date photographs that reflect the society we live in. Their need is so great (they produce several dozen periodicals and as many book titles each year) that editors keep a permanent file of transparencies, black-and-white prints and color photographs in their art libraries. Some publishers maintain a digital collection. These photographs are chosen because of their broad appeal to the particular readership reached by that publishing house. The editors welcome additions to this file to keep on hand for immediate use when needed.

Photo buyers are fond of saying, “Send me pictures that I can always find a place for in my layouts.” Of course, it would take a mind reader to score every time, but if you’ve been successful in selling to a certain market several times, in all probability you have a keen understanding of the photographic needs of that publishing house. Ask all your photo editors if they have a permanent file; if they do, submit your pictures for consideration. Your photos can be included in the file, and each time a picture is used, you will receive a check. Most photo editors prefer original slides, and you may not wish to place your originals with a central art librarian. However, the system works well for black-and-white prints, color prints and digital files. Some textbook publishers will accept display dupes as file copies.

Can you depend on publishing houses to be financially conscientious in their dealings in this kind of arrangement? In my experience of more than three decades, yes. The risk factor of a mix-up in use and payments is low to nonexistent. When you balance an honest mistake every now and then against all those checks you would not have received if you had never placed your pictures with the permanent file, your choice becomes obvious. Your greatest risk actually will be investing in multiple color and black-and-white prints and then relying on your judgment as to which publishing houses would be likely to use them most frequently.

As publishing houses become more sophisticated in developing digital files, the problem of sending original prints and slides to photo editors will diminish. However, you will find that most editorial publishers are more interested in having a print or slide readily available, rather than the computerized version. Is this laziness? In some cases, yes. In reality, though, given the human tendency to resist change, most editorial photo buyers will defend the present way they are conducting business. As the new breed of photo editors comes on the scene, you can expect a shift to more use of digital files and research on the World Wide Web.

From time to time, you’ll want to update your supply of work on file by sending a fresh batch of photos. From time to time, too, the art librarian will return pictures to you to make room for more recent submissions.

The Pirates

Some photographers new to photomarketing bring with them misconceptions about the ethics of photo buyers. From my conversations and correspondence with beginners, I’m always amazed at how many have visions of picture-buyer pirates lurking in their office coves, ready to seize some unsuspecting photographer’s pictures and sell them on the black market.

Such infringers might exist in the field of commercial stock photography, where stakes for a single picture are known to reach impressive heights (such cases are reported in trade journals such as Photo District News); however, in thirty-five years I have never run across a deliberate case of piracy in the editorial field. An occasional inexperienced photo buyer may make an error of omission or commission. Photographers have been known to do likewise. The lesson here is to be cautious when working with new publications that don’t have a substantial track record, or a third-world publishing house that may be unaware of international copyright law, or publishing houses that have a history of hiring greenhorns. I suggest that you deal with publishers who have been in business for a minimum of three years.

The Legal Side

If you’re just starting out or starting over, don’t be tempted to include the highly legalized transfer documents that are sometimes recommended by the American Society of Media Photographers (ASMP). These can be a definite turnoff to your would-be photo editor. In the early stages, expect to work on a handshake basis. Later, when you’re on a first-name basis with photo buyers or they have invited you to call them collect, you can introduce ASMP-type forms with all their legalese and fine print. This doesn’t mean that you shouldn’t include any paperwork at all; include a simple delivery memo and a cover letter.

All in all, you’ll find photo buyers of stock photography reliable and interested in you as a person and as a photographer. If you operate with the same attributes, you’ll find dealing with photo buyers to be an easy task.