The last cyber activity involved in waging war within the cyber domain is intelligence gathering which is integral to the success of any military operation. Whether it is done to support a Title 10 military operation of general national defense purposes supporting situational awareness, intelligence gathering is strictly a Title 50 effort. Unlike cyber-attack activity, intelligence gathering does not always rely upon cyber exploitation as an enabler.

SIGINT —Signals intelligence is derived from signal intercepts comprising -- however transmitted -- either individually or in combination: all communications intelligence (COMINT) , electronic intelligence (ELINT) and foreign instrumentation signals intelligence (FISINT) . The National Security Agency is responsible for collecting, processing, and reporting SIGINT. The National SIGINT Committee within NSA advises the Director, NSA, and the DNI on SIGINT policy issues and manages the SIGINT requirements system.

IMINT —Imagery Intelligence includes representations of objects reproduced electronically or by optical means on film, electronic display devices, or other media. Imagery can be derived from visual photography, radar sensors, and electro-optics. NGA is the manager for all imagery intelligence activities, both classified and unclassified, within the government, including requirements, collection, processing, exploitation, dissemination, archiving, and retrieval.

MASINT —Measurement and Signature Intelligence is technically derived intelligence data other than imagery and SIGINT. The data results in intelligence that locates, identifies, or describes distinctive characteristics of targets. It employs a broad group of disciplines including nuclear, optical, radio frequency, acoustics, seismic, and materials sciences. Examples of this might be the distinctive radar signatures of specific aircraft systems or the chemical composition of air and water samples. The Directorate for MASINT and Technical Collection (DT), a component of the Defense Intelligence Agency, is the focus for all national and Department of Defense MASINT matters.

HUMINT —Human intelligence is derived from human sources. To the public, HUMINT remains synonymous with espionage and clandestine activities; however, most of HUMINT collection is performed by overt collectors such as strategic debriefers and military attaches. It is the oldest method for collecting information, and until the technical revolution of the mid- to late 20th century, it was the primary source of intelligence.

OSINT —Open-Source Intelligence is publicly available information appearing in print or electronic form including radio, television, newspapers, journals, the Internet, commercial databases, and videos, graphics, and drawings. While open-source collection responsibilities are broadly distributed through the IC, the major collectors are the DNI's Open Source Center (OSC) and the National Air and Space Intelligence Center (NASIC) .

GEOINT —Geospatial Intelligence is the analysis and visual representation of security related activities on the earth. It is produced through an integration of imagery, imagery intelligence, and geospatial information.

Cyber Intelligence Gathering

Though not called out specifically, intelligence gathering within the cyber domain logically falls under the SIGINT method of intelligence gathering. The interesting thing about cyber intelligence gathering under the SIGINT discipline is that it allows intelligence gatherers to potentially gather intelligence that correlates to each of the six disciplines. For instance, in accessing enemy computer systems and conducting cyber intelligence gathering, images might be found stored on the computer system, tying SIGINT and IMINT together. It is also possible that measurements and technology documentation about enemy systems could be found on computing systems of the enemy, tying SIGINT and MASINT together. If the cyber domain was used to solicit human sources via social media and other digital mediums, it would tie HUMINT to SIGINT. If the cyber domain was leveraged to gather information from foreign state news web sites, it would tie SIGINT to OSINT. If cyber activity was used to gather data from the foreign equivalent of Google Earth pictures, maps, and geolocation of a foreign adversary location over time to put together an understanding of that adversary, it would tie SIGINT and GEOINT together. This matrixing of intelligence mediums is unique to cyber intelligence gathering.

Strategic Intelligence —inform and enrich understanding of enduring national security issues;

Anticipatory Intelligence —detect, identify, and warn of emerging issues and discontinuities;

Current Operations —support ongoing actions and sensitive intelligence operations.

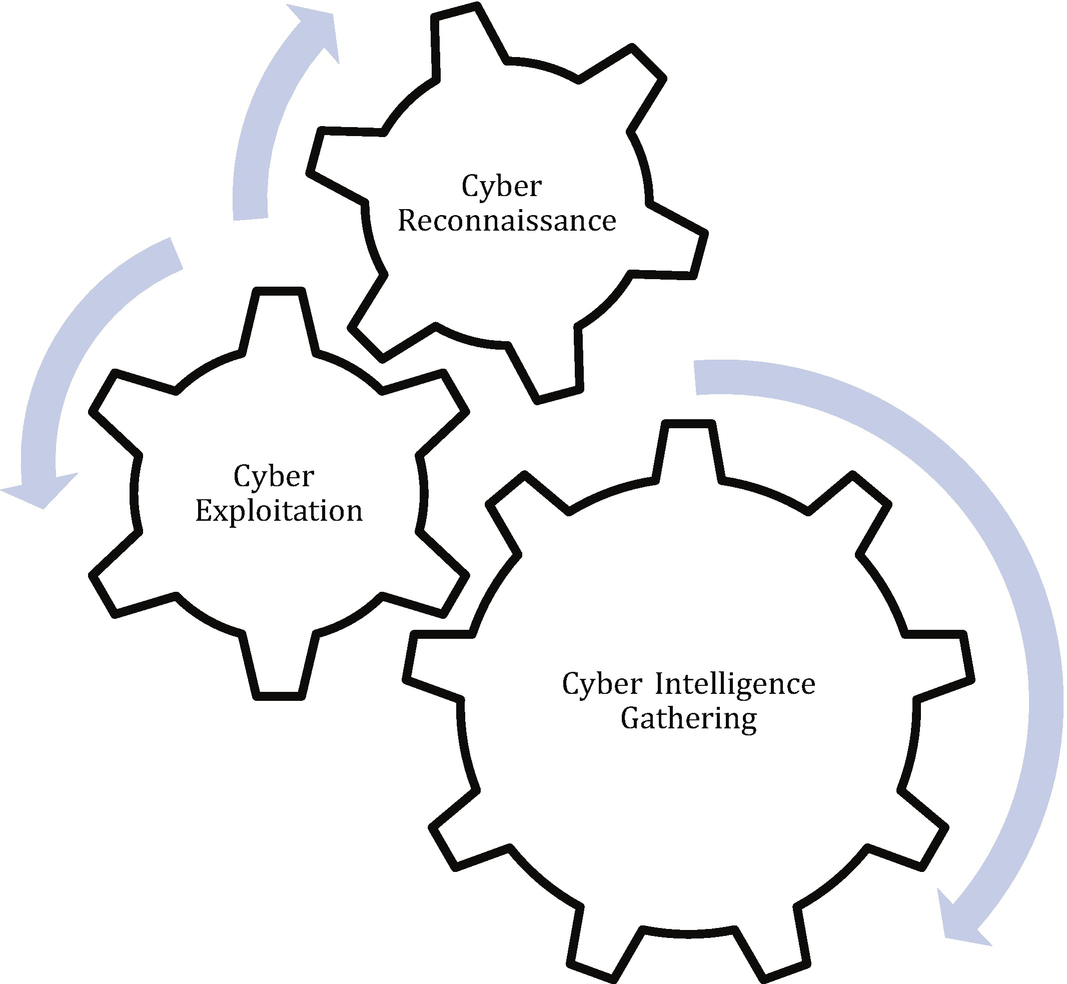

Something that stands out regarding intelligence gathering in the cyber domain under the SIGINT discipline is that for any intelligence gathering that needs to be enabled by cyber exploitation, there is a need to have prior intelligence gathering to determine how to accomplish that exploitation against intended targets. I will refer to this activity specifically as cyber reconnaissance, which is meeting the third objective of supporting current or ongoing operations. Here, the intelligence doesn’t necessarily serve a strategic need of the IC or even benefit anything outside of the current intelligence gathering operation as it is used to survey the attack surface of the target within the cyber domain to determine best paths of increase access and in furtherance of operational goals.

Cyber intelligence is therefore any intelligence gathered in the cyber domain that will help target additional assets or garners information for strategic or anticipatory objectives, and cyber reconnaissance is specifically intelligence gathered from a target that is used to exploit and access cyber systems. Cyber reconnaissance is also necessary in any exploitation utilized to prepare a battlefield for or simply execution of cyber-attack activities, as there is a need for information that will lead to targeting and successful attacking of enemy assets. There is no difference in authority as both the gathering of cyber intelligence and the performance of cyber reconnaissance are under Title 50, the difference is the customer of the data being gathered. Cyber reconnaissance data furthers a cyber domain operation and is likely consumed most importantly by the entity conducting that cyber domain operation. Cyber intelligence is gathered for the customers who are likely to perform intelligence analysis.

Cyber Domain Intelligence Collection

Cyber Domain Cyber-Attack

Cyber Domain Collection Examples

Just as we did with exploitation and attack activities, I will walk through some different examples of intelligence gathering to really drive home an understanding of what it looks like when performed in the cyber domain. I have split these examples into four operationally different efforts of cyber intelligence gathering.

First and foremost, cyber intelligence gathering can be done using the discipline of OSINT or open source intelligence, which is the obvious example for intelligence gathering that does not require exploitation as the sources of OSINT information are publicly available. Cyber intelligence gathering can also take on the methodology of HUMINT when the cyber domain is simply the conduit between the requester of the HUMINT and the source. Instead of meeting in a dark alley to exchange information or approach potential sources, it can be done more safely and anonymously through the cyber domain.

The last two types of cyber intelligence gathering operations are directed and indirect. Directed is the purposeful collection of specific information from any of the six disciplines off of a target cyber system. Indirect cyber intelligence collection is any effort aiming to collect data about cyber systems but not from them which is also known as metadata. Metadata is simply data that tells information about other data.

To understand this concept, think of a delivery truck. The data in question, or rather the intelligence needed, is what the delivery truck is carrying inside. Opening the backdoors to the truck would certainly let you know what the cargo was and that would be direct data gathering. Indirect data gathering would be looking at information about the truck such as its speed, direction of travel, how low it is riding on its suspension, what is written on the side, and other details that can be used to help determine what it might be carrying. These are examples of metadata collected indirectly.

The following collection examples will mostly maintain the theme of an enemy with extremely important oil interests.

Open Source Collection

Open source collection is that which requires no special access or authorization and can be collected from publicly available sources.

Non-cyber Example

Overt observation is the most straightforward example of OSINT. The target is in no way attempting to disguise or camouflage something, and the observer is in a location and context that required no extraordinary enabling efforts such as illegally entering a country or sneaking into a secure area. To accomplish OSINT collection against the oil-dependent enemy state, an agent takes an extended vacation to a country that shares a bay with the enemy. Weekend after weekend the agent charters fishing boats in the bay which is also home to the main oil port of the enemy state. The agent hasn’t illegally entered the neighboring state and simply takes photos every weekend during fishing charters to build a pattern of life about the oil tankers coming and going from the enemy port to potentially aid in targeting them for escalated action.

Cyber Intelligence Example

Using OSINT in the cyber domain to gather intelligence about the enemy state is very similar. The agent uses publicly available data from stock market tracking web sites to monitor the activity of the stock listing for the enemy state-owned oil corporation. Over a long period of time and gathering many data points, this type of intelligence could lead analysts to determine that every February there is a huge surge in stock activity with the state-owned oil corporation holdings for one reason or another. This could be used to time a cyber-attack against the corporation when it seasonally has the highest amount of stock activity to cause the most financial and reputational damage.

Cyber Reconnaissance Example

OSINT can be very valuable for exploitation efforts aimed at gaining access to enemy systems within the cyber domain. Surprisingly organizations often publish on their web site or even in news media that they have just undergone a technology upgrade and sometimes more details than should be divulged. Imagine the enemy state announces they have upgraded their entire stock exchange systems to facilitate faster trading and that they are using the latest of a certain brand of server to process trades quicker. They also state when the install began and that it was just finished. An attacker may be able to determine that based on the model and when they were installed what the operating system version is and be able to research vulnerabilities to leverage against the system. Worse, an attacking nation state with the time and resources might just go buy the same hardware and install the same software likely to be on that hardware based on the dates in the article and do their own reverse engineering to find new vulnerabilities.

Human Source Collection

HUMINT using human assets to ascertain intelligence is very close to espionage just as manipulation attacks are also similar in conduct. The focus of distinction is again on the motive and goal. HUMINT can be very overt, when done under Title 10 in preparation of a battlefield. Here, a likely uniformed military member may ask a human source to come back in the morning with a count of how many enemy combatants were seen entering a complex during the night to better prepare to attack that facility.

Under Title 50, more covert agents or handlers are managing assets to gather intelligence inside and against the enemy state. In this situation the covert handler may ask the human asset who owns a food stand to return and give information such as car type, clothes worn, and so on when a certain person is seen in a market to help target that individual for further intelligence gathering or kinetic actions. Espionage would be having a covert agent or handler ask their human asset to start a rally in the enemy state capitol to try and get a violent response out of the government and increase sympathy in the enemy state for rebellion with the eventual goal of toppling that government.

Non-cyber Example

A non-cyber, traditional HUMINT example concerning our overall theme would be having local farmers with land along roads to main oil distribution centers keep track of how often, how many, and what direction oil shipments using truck are headed and reporting back with that information on some regular basis. This type of information can be used to learn more about potential production and sales levels as well as lead to better targeting of oil distribution centers for better effect than would be accomplished without such information.

Cyber Intelligence Example

To gather intelligence using human assets in the cyber domain, an often-frequented source of information is likely chat rooms and message boards. In this example the handling party would look for a source who was willing to participate in these forms of communication with actors from the enemy state. For instance, if the source was recruited at a petroleum industry business conference, the source may be asked to cozy up to businessmen and women from the enemy state-owned oil corporation and hope to get on to professional message boards or in chat rooms with those individuals and report back routinely with information.

Cyber Reconnaissance Example

Using cyber domain-enabled HUMINT to better operational capabilities through cyber reconnaissance is a bit less straightforward than the other examples. To get information that would lead to easier exploitation and access of the state-owned oil corporation, you could make fake job postings in information technology fields that were very appealing to get as many candidates as possible but with the specific goal of finding applicants who currently or previously worked at the state-owned oil corporation. In interviewing these applicants, you would be looking to get information from them regarding technologies they worked on at the oil corporation or other information relevant to the targeting of cyber domain systems of interest.

Physical-Cyber Example

Since we addressed the aspects of cyber-physical operations in the cyber-attack chapter, I thought it would be interesting to represent the opposite type of operation regarding intelligence gathering. Cyber-physical actions are those where execution of an activity in the cyber domain has tangible effects in another warfighting domain such as air, land, sea, or space. Conversely, physical-cyber operations are those where activity in the physical domains enables effects or activities in the cyber domain. An example of this that falls within the human source collection methodology involves leveraging an asset to perform an action with something physical, such as installing a piece of software that logs keystrokes on devices, he or she has physical access to. If an asset was tasked with installing such software in an internet café they frequented and that software logged what was typed on the installed computers and sent the data back to the collecting party, this would be an example of a physical-cyber human-sourced collection activity.

Direct Collection

To reiterate, direct collection is the act of taking data from a target system in the cyber domain. That data may be from any of the six intelligence collection disciplines (SIGINT, OSINT, HUMINT, MASINT, IMINT, and GEOINT) due to the nature of data that can be found during cyber intelligence collection.

Non-cyber Example

A non-cyber-directed intelligence collection effort would be having an agent sneak into the oil corporation headquarters after hours, breaking into the executive offices and taking pictures or making copies of (both technically IMINT) sensitive information that will be passed along for analysis. Since human beings have competed with each other for resources, direct intelligence collection was actually primarily done through means of HUMINT, though with the advent of the computer age and imagery satellites that has certainly changed. As such another good example of non-cyber direct collection is in fact imagery aircraft and later imagery satellites that circle the Earth taking pictures (IMINT) of areas of interest. Technically in modern day, this would be considered OSINT, but in times such as the cold war where satellite photography was not well known, and spy planes were shot at when entering enemy airspace, it was certainly not open source.

Cyber Intelligence Example

An example of direct cyber intelligence collection would be using a cyber tool to collect emails from important individuals off of an enemy state server. These emails could include any information and are not likely all of intelligence value (cat pictures). That doesn’t mean that they won’t sometimes contain overly sensitive and valuable information that they aren’t supposed to. Collection of enemy state emails might focus on when oil sales are made. Such efforts might also be against military or government email servers to collect anything from future plans to troop movements and supply statuses.

Cyber Reconnaissance Example

This is probably the most appropriate example and easiest to understand of all. Efforts of direct cyber reconnaissance to further cyber domain missions involve any sort of scanning or target enumeration to identify vulnerabilities on a target system or in a target network. Cyber reconnaissance is not always this straightforward though and can be quite complex. Instead of looking for intelligence on an email server like the proceeding example, we could only focus on the email accounts of known IT and administration personnel. This is done in hopes of coming across an email with passwords or other target system information that could further enable access to the enemy state attack surface.

Physical-Cyber Example

A physical enabled example of direct intelligence collection within the cyber domain could be as simple as having someone plug in a thumb drive to computers at a business conference where the enemy state oil corporation was represented. A tool on the thumb drive would infect the machines it was plugged in with a backdoor that allowed cyber actors to access the enemy system for further actions such as intelligence gathering. This type of physical-cyber activity is particularly effective when systems are not available to access in some way from the internet due to not living on any sort of network connected to any other networks. In this case, physical-cyber efforts may be the only way to access those target systems.

Indirect Collection

Indirect collection is the act of gathering information about a target cyber system and not from that cyber system. The information collected this way is often referred to as metadata.

Non-cyber Example

Indirect collection against the enemy state could involve using imagery from a satellite taken routinely over the main port used by the enemy oil corporation. These photographs would reveal the tankers as they come and go. This imagery might allow the gathering party to identify how much oil is in the ships by how low they are sitting in the water. The direction of their travel and flags they are sailing under might tell the gathering party who is buying the oil. Both of these pieces of information would prove valuable in an effort to analyze the compliance with sanctions of involved parties.

Cyber Intelligence Example

Indirect cyber intelligence can be gathered in many ways but often focuses on communication relationships. This means a focus on who is talking to who, for how long, when, and from where. This stays indirect if it is only a collection of metadata and not the actual content of those conversations. Exploitation of an enemy state email server or cellular phone database allows for this type of data to be collected. It may seem invaluable to not get the actual conversations, but this type of collection does lend itself better to data analytics which could lead to more appropriate targeting for direct collection. Further, files of conversations, if they even existed, would likely be much larger than just aggregating the metadata of conversation relationships, and it is probably more efficient than an effort to go through than listening or reading a bunch of conversations.

Cyber Reconnaissance Example

Indirect cyber reconnaissance focuses on the same attributes of communications, who talks to who, for how long, in what manner, and when. This time though, the focus might be on gathering a baseline for how systems on a target network communicate over the course of weeks. With this information in hand, further activity in that target network can be tailored to blend in more with the expected traffic and lower the risk of detection. This would allow cyber domain operations to potentially continue more efficiently and unimpeded in the cyberspace of the enemy state.

Physical-Cyber Example

What if we needed to know the metadata on phone conversations in an enemy state but we didn’t know where to find or how to access the digital databases in the cyber realm that had that information. We could leverage physical access to cell towers on the border with the enemy state and have an actor physically attach hardware to a few of the cell towers that would record this metadata for us and send it out over cellular communications to be collected. This is obviously not as stealthy as doing it entirely within the cyber domain, but it could be the only option.

Understanding the Trade-Off

The most important take away from this chapter and the two that proceeded it is that there exists both interdependencies and trade-offs when making the decision to conduct a cyber-attack. Where exploitation and its enabled intelligence collection may go years without being detected, if ever, cyber-attacks immediately bring attention to the attacker presence within the enemy cyberspace. The technical ramifications posed by the relationships between exploitation, attack, and intelligence gathering will be covered in depth in a later chapter. At the non-technical level, there is the simple concepts of being noticed and being attributed, an enemy that successfully does both has caught the perpetrating entity, and whether intended as an act of war or not, that activity may be considered by the target state as cyber warfare and directly lead to declared and open conflict.

It all comes down to a cost-benefit analysis of the situation. Is it worth losing potentially years of future collection opportunity in a target network to conduct a single cyber-attack? There is no one answer; it depends on the value of the intelligence and the value of the attack. Is it better to eliminate a single capability being developed by an enemy or is it worth being able to monitor the capabilities they develop over the course of an entire conflict or longer? Is it worth shutting off power via malware deployed to power stations in certain areas to hinder the enemy or is it more important to be able to keep the power on and track their movement and actions using exploited state digital surveillance devices? A cyber-attack may save the life of a covert asset in the enemy state by deleting camera recordings, but intelligence gathering over the course of years from that same camera may have prevented the loss of countless lives by providing information that stopped several terrorist attacks.

The weight and authority of such decisions is why cyber-attack falls under Title 10 authority and military command and the applicable oversight to those actions. Though it may not initially have sounded like a very military domain of warfighting, hopefully now the cyber domain can be seen as equally requiring the same doctrine needed when making command decisions that may lead to the loss of some lives in the protection of the many.

Summary

In this chapter we covered the topic of intelligence gathering, how it is defined, and how it relates to and within the cyber domain. We covered multiple examples to gain an understanding of how intelligence gathering within the cyber domain falls into the four collection categories of open source, human source, direct, and indirect. The difference between cyber intelligence gathering and cyber reconnaissance was also discussed and shown through examples. Lastly, the impact of cyber-attack activities to intelligence gathering efforts was highlighted as a matter of extreme importance and a likely motivation for placing attack effects in the cyber domain under the charge of warfighting commanders and the authority of the Department of Defense.