In an age of interconnectivity and within a domain of cyber centered around the internet, it should be no surprise that cyber domain activities are nearly incapable of cross or interacting with devices belonging to neither the aggressor nor victim state in any cyber warfighting activity. In most imaginable cases, the internet or World Wide Web plays a key role in the conduct of cyber domain actions. The term internet itself belies the origin of its creation for internetworking, and the Web in World Wide Web is a simple and powerful indicator to the messiness in cyber communication paths. The internet revolves around a lack of regulation and singular ownership, where devices owned by organizations and individuals all across the world communicate in common protocols.

Due to this interwoven and unregulated communication forum, it is almost impossible for a cyber domain activity to make it from perpetrator to victim without being processed or interacted with, and therefore potentially associated with, by some device external to the victim-perpetrator relationship. It is worth discussing how this fact should impact cyber operations. Is association avoidable? Should it be avoided? Is it useful to manipulate association? These questions and others relate to this issue which is unique to the cyber warfighting domain. One way of understanding this unavoidable aspect of the cyber domain is to consider an analogy using sovereign airspace. If the United States, for instance, wants to drop ordinance on another country in a declared conflict, there is certainly the potential that the aircraft which drops that ordinance did so after crossing external sovereign airspace belonging to another state or states. In such cases, it is not typical to view the various countries whose airspace the US aircraft crossed to be complicit in the dropping of the ordinance on the enemy country. In fact, in most cases the United States has alliances and other international agreements where it is allowed to fly its aircraft through other countries’ airspace and is therefore not in violation of their sovereign airspace. Flying an aircraft through a nation’s airspace is easily understood as not associating that country with the activity being conducted by the perpetrator.

Unfortunately, this logic fails when applied to the cyberspace scenario. To relate the two, consider the following. Instead of flying through another country’s airspace in a US aircraft to drop ordinance, imagine the US plane had to land in each country along the way. More than that, it had to land, be placed on board a larger plane belonging to the state whose airspace it needed to cross, then flown in that larger plane across the country’s airspace. Next, at the border, the US aircraft would have to be moved into another of these larger aircraft, this time belonging to the bordering country, to then be hauled across its airspace. This process would be continued until the aircraft got to the border of the intended victim for the ordinance drop where the US craft would embark once again on its own into the sovereign airspace of the enemy victim and ultimately drop its ordinance. In this example association between the perpetrator and the countries whose airspace needed traversing is much stronger; after all, they actually loaded the US plane and the bomb it carried onto their own aircraft and then transported it toward the intended victim. In such a situation would it be harder to argue the associated transporting states were not in some way complicit with the attack?

Though seemingly ridiculous, the airplane scenario is very analogous to how cyber warfighting activities traverse the internet. Data which ends up exploiting, maintaining access to, attacking, or returning intelligence data from enemy systems is potentially sent from a perpetrator-controlled device, across a network of uninvolved third party–controlled devices until ultimately passing into the enemy system to perform its intended function. Each device along the way unwraps the data packet, processes the routing data used to let the packet navigate the internet to its intended destination, repackages the data packet, and sends it to the next devices along the way.

- 1.

1.1.1.101 – This is the address of the device 1.1.1.1 knows to send traffic to for further routing

- 2.

1.1.2.101 – This is the address of a bigger internet service provider (ISP) bigger routing device that knows about more addresses

- 3.

1.1.3.101 – This is the address of a main U.S. device that knows how to rout to the U.K across the Trans-Atlantic cable

- 4.

2.2.3.101 – This is the address of a main U.K device that knows how to rout to the U.S. across the Trans-Atlantic cable

- 5.

2.2.2.101 – This is the address of the device in the U.K. that knows how to get to other countries in Europe

- 6.

5.5.2.101 – This is the address of a device in France that knows how to get to other countries in Europe

- 7.

5.5.1.101 – This is the address of a device in France that knows how to get to the specific destination address of 5.5.5.5

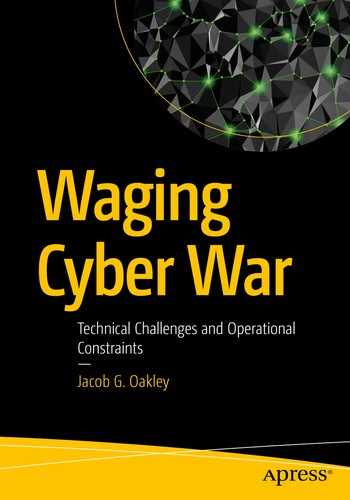

This routing example is very similar to how the postal mail service works. If you live in a small town and you are sending a letter internationally, your small local post office does not send the letter directly to your destination, it routes it to bigger and bigger post offices until your letter reaches one which handles international mail. From there it is sent to the foreign country where it is passed back down the chain to smaller and smaller post offices in the destination country until it ends up at the local destination of your address.

Package/Packet Traversal Comparison

At some point, or at what point, is a third-party country’s mail service, or in the case of the cyber domain, internet routing device, responsible for the contents it couriers. Understanding the ways in which association can be implied, applied, and understood is necessary in an age of cyber warfare. Without such an understanding, the second- and third-order effects of such association cannot be mitigated or controlled. Association can result in breaches of international convention, committing war crimes and breaking or invoking alliances by implicating the potentially uninvolved.

Types of Association

The implications of association can certainly be concerning and more than worth the time to scrutinize. In fact, with the power to in the very least optically implicate a third party in warfighting actions, there are both purposeful and incidental associations which may occur during a cyber domain activity. Approaching purposeful association with measure and tact while avoiding unintentional association wherever possible is a must in cyber warfare.

Incidental

The potential for incidental association is almost impossible to avoid in many cases. Often the way in which cyber activity is conducted requires traversal through the cyberspace of multiple third-party nations on its way to the target destination. This leaves the door open for possible association of those third parties with the attack action even though it originated in a separate place. This type of incidental association is external to the target organization and for obvious reasons raises some concern for potential repercussions against those uninvolved in the conflict whose devices were leveraged in the delivery of cyber actions.

There is also the concept of incidental internal association. In this case, it is not an external third-party nation state associated with a cyber action but an internal device and/or user. In incidental internal association, it is not the devices handling and routing traffic which end up associated with the activity. Being internal to the organization, the administrators or security and monitoring staff of the organization or even nation state likely control and can forensically inspect the devices after the fact at the internet service provider level or internal to the actual target if necessary. This level of access means that though those internal to the nation devices were routing the attack activity, association can be ruled out as benign from the perspective of the owning party within the target state.

On the other hand, consider a host compromised via a spear phishing attempt in which a user opens a malicious email, visits a malicious link, and through their actions executes malicious code from an enemy state. If the attacker is careful enough, even cursory forensic activities on the compromised computer may not reveal the presence of an outside attacker. In this case the organization or state may assume the individual is an insider threat and act against them accordingly. This has many but different impacts than incidental external association but is itself worthy of careful consideration. Incidentally associating an internal device and its owner with something such as cyber-attack actions could result in that person being deemed an insider threat, traitor, or enemy plant. Those conducting cyber-attack activities must consider the ramifications of accidentally letting incidental internal association happen as it could ultimately lead to the death of the internally associated individual or individuals.

This is the best place in the book to also address a non-association-related issue that can also result in the potential firing, incarceration, or even death of innocent bystanders. In the other warfighting domains, air, land, and sea, the sovereign area belonging to a nation state is clearly defined and also likely protected in some way by a military entity. The cyber domain of warfighting consists of an attack surface for each nation made up not only of military assets and individuals but also government civilian assets and individuals. I can certainly think of a few countries where a contractor or government employee administering important devices which ended up being used to launch or were the target of a successful cyber-attack effect might be severely punished by incarceration or death if it there was even a perception the attack could have been prevented. Even were this not the case, I think in many if not all nations such an individual who did not protect or detect such an attack would find themselves jobless. International convention and laws of war may never address this issue, in any case a nation state conducting warfare in all domains, including cyber, should take care to avoid implication, associating or damning bystanders in the carrying out of warfighting actions. This is especially the case in cyber where the danger of such unintended consequences on innocents is a dynamic and difficult challenge.

Purposeful

The fact that incidental association will happen is easily understood though clearly the implications are a web of unfortunate and unintended consequences. Purposeful association is the process by which the nation state perpetrating cyber warfighting activity willingly associates that activity internally and/or externally, in one way or another, to satisfy various motivations.

For Obfuscation

Purposeful external association to provide obfuscation involves any effort to tie cyber activity, its origination, and potentially its motivation to devices, individuals, and organizations or nation states in an effort to hamper forensic efforts by the target at identifying the source of the cyber-attack. If done correctly, this type of activity can help prevent the attribution of the perpetrating state while not implicating the involvement of third parties through association. This is the difference in purposeful and incidental association—in purposeful association, the information the enemy has access to regarding where an attack came from is at least in part supplied in intentionally conflicting and complicated ways.

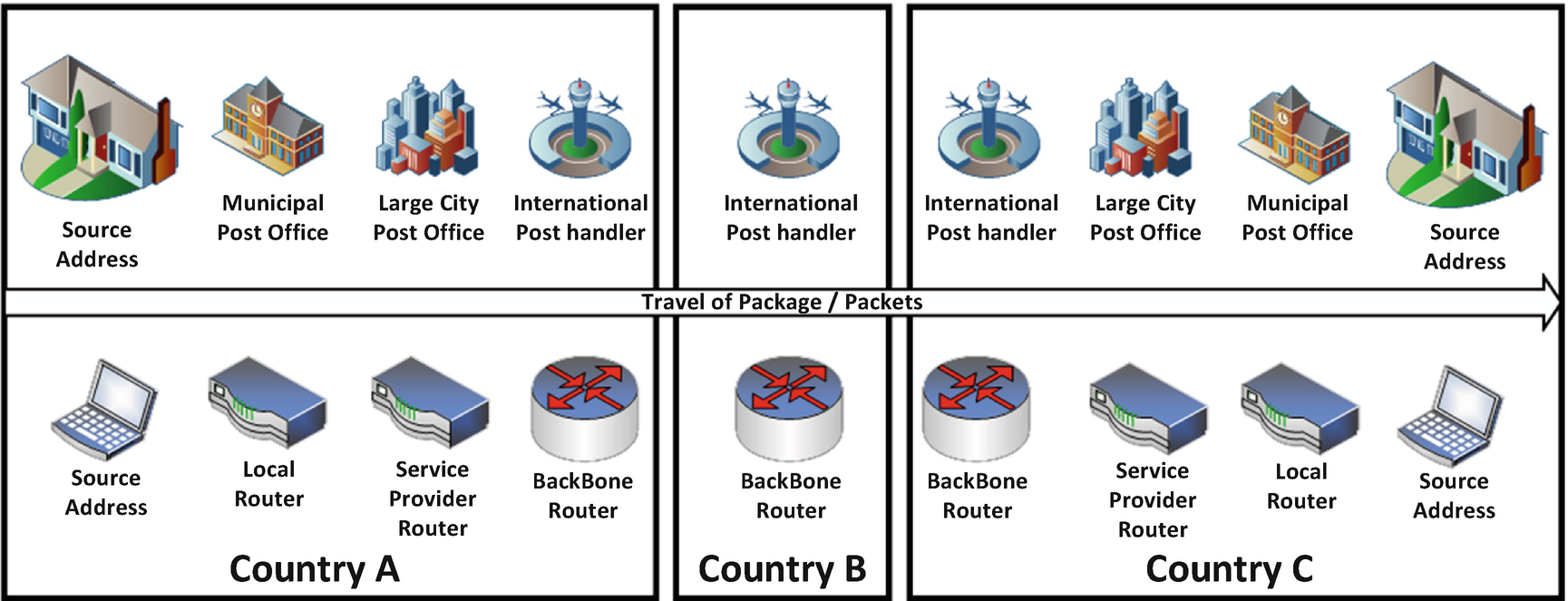

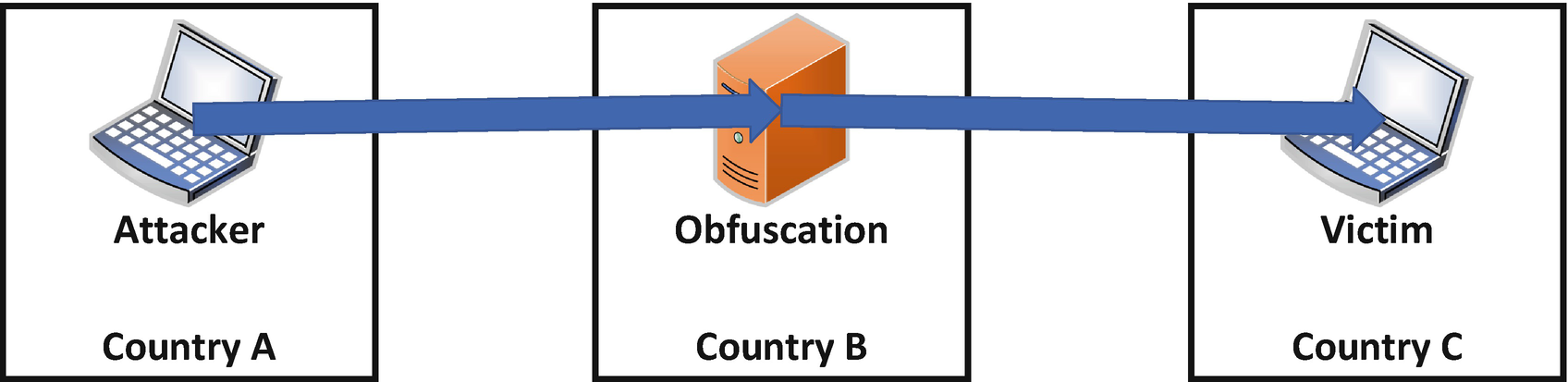

External to the target, this would involve an effort to utilize multiple redirection points immediately prior to launching the attack or exploitation activity as well as creating a chain of devices which redirect the traffic prior. Redirection points are simply devices placed or exploited for the sole purpose of altering the path and direction of network traffic between the perpetrator and victim. In this way, through the involvement of many dispersed and chained points of redirection, a perpetrating actor can both obfuscate its own location and actions and avoid a third party being identified as associated and potentially complicit to the attack activity. It is one thing if the attacked organization sees the cyber-attacks being launched via traffic all originating within a single third-party nation state, which may negatively associate that state with the action. On the other hand, if the redirection points are in several nation states or, even better, are coming from known cloud hosting service addresses in several locations, it is both obvious that the perpetrator is trying to cover its tracks, which protects the third parties associated with the redirection points, as well as making it unobvious where the attack actually came from.

Singular Obfuscation Resource

Multiple Obfuscation Resources

Purposeful internal association in an effort to obfuscate is more about protecting access to the target and an ability to carry out the intended warfighting activity than to prevent self-attribution, as that is more relevant in external obfuscation. Internal obfuscation involves creating redirection within the target state organization or network to attempt associating attack effects with one set of compromised hosts and current and future access operations with others. In this way the perpetrating state hopes that upon launch of a cyber-attack effect, that action will be forensically tied to hosts that have nothing to do with the way the network was initially accessed. In this same manner, the perpetrator’s presence in the network can be obfuscated to simply complicate forensic activities by the target state as well. In both cases such internal obfuscation via association helps to avoid self-attribution as well as enabling resilience in the ability to access the target and deliver attack tools prior to the attack being launched.

To Distract

Whether done internally or externally, using association to distract the target of a cyber activity is in the gray if not on the bad side of ethical implications, especially in regard to attack effects. Where obfuscation aimed to prolong identification of the perpetrator through varied associations, distraction aims to clearly associate a singular third party in hopes that the effort spent by the target in researching, engaging, or responding to that third party will benefit the perpetrating state. As with obfuscation, the purposeful nature of association to distract afford the perpetrator more control over the association aspect of cyber operations and the resulting impacts.

Distraction through external association can be responsibly done. Irresponsible distraction would be one that resulted in the association of a third party with the cyber activity to the point of even implicating they are not only associated with, but the likely origin of that action. In this case the third party is at risk of facing warfighting responses from the target state due to the poor tradecraft of the perpetrator. Responsible distraction would be one which made the same clear association with a third party but where that third party is not likely to suffer warfighting repercussions. Aside from the method of association is the chosen entity to associate with the activity.

For instance, if the United States attacked Pakistan with a cyber-attack effect but made it appear that the attack was associated with India, such purposeful association would be irresponsible. Pakistan would likely not waste much time looking into the validity of that association and may even simply use the fact that the attack appeared to originate in India as an excuse to launch its own warfighting actions. In a different scenario, if the United States attacked Sweden but made the cyber-attacks seemingly associate with Norway, it would be much more responsible.

Sweden, knowing Norway has no reason to seek aggression against it, would certainly take a long time to dig into the details of the cyber-attack and its association with Norway. In such an example, Norway and Sweden are even likely to cooperate to determine who the real perpetrator was. In this case, if they ever even determined it was the United States that launched the attack, the obvious association with Norway would have distracted the target long enough for the United States to accomplish further actions, in the cyber realm or others, knowing its target was off its trail for some time.

Accomplishing distraction through association internal to a state is accomplished in the same way as before and has the same responsible and irresponsible potential executions. If the attacker made strong associations with the attack effect coming from a random user in the target organization, it could be irresponsible as that individual may be responded to as an insider threat or traitor. If instead the association was tied to some other organization within the enemy state, the association would serve more as a distraction while the enemy dug into why it appeared one of its organizations was attacking another. Imagine a scenario where devices owned by the US Navy were clearly associated with carrying out cyber-attack effects against the US Army. There would be no warfighting response by the Army against the Navy, but the association would distract the Army by forcing them to investigate why this appeared to be the case. In such examples, the forensic efforts needed to rule out the association in fact tie up multiple organizations including the target and the associated entities in the enemy state as they determine why that might be.

To Self-Attribute

We have already covered the concept of purposeful self-attribution, but it is worth tying back into the association concept. Purposeful self-attribution can come through near immediate declaration by the perpetrating state of what cyber warfighting activities were carried out. This is not always ideal as perhaps the warfighting activity is not desired to be announced yet as it might implicate or endanger other operations simultaneously going on or planned in the future. Purposeful association offers a way to skirt some of the negative repercussions to outright declaration of cyber warfighting activities, especially political ones. It can do this while still avoiding unintentional associations and the second- and third-order effects that might result. If a state strongly associates its warfighting activity within the cyber domain as coming from itself, but does not openly declare the actions, it allows for the enemy to, with a high level of certainty, know who carried out actions against it. This avoids inappropriate responses to potentially associated third parties. It also allows the perpetrator to openly refute any claims of the attack by the target on the international stage to dance around any political issues while still projecting force to the enemy.

As a Weapon

With all the potential ramifications of association, both purposeful and incidental, it is pretty clear that there is a potential for the perpetrator to leverage the association of cyber-attack effects with certain entities as a weapon in and of itself. In this case, the goal of the perpetrator is to illicit responses by the target against the associated entity in furtherance of the perpetrator’s strategic goals.

Using external associations in this manner is a tweak on the concept “The enemy of my enemy is my friend.” In this case though, I want to encourage my enemies to become enemies of each other. Imagine a country wanted to launch cyber-attack effects against Russia, but also wanted to illicit cyber warfighting responses against another enemy it had in China. Now, China and Russia are openly pretty friendly; however, both have a strong reputation for meddling in the cyber domain of other countries. Getting Russia to think a cyber-attack came from China with enough fidelity to incur an actual warfighting response against China by Russia will take more than the efforts discussed so far in obfuscating and distracting mostly through choice of redirection. In this case the perpetrating state of the attack against Russia will want to make it look like it didn’t just come from China but that it was China. This could be done by establishing an association with China through strong attribution of the actions leading up to the cyber-attack as being tied to a known Chinese actor. The perpetrator would research a specific Chinese actor, its historical activities, tradecraft, and tactics and try to understand its motivation and use similar tools as well. In this way, the perpetrating state so strongly associates the cyber-attack effect with a specific Chinese actor that Russia has no choice but to respond against China. In this way association was weaponized to not only attack one enemy but get that enemy to lash out against another enemy of the perpetrating state.

Where weaponizing association external to the target involves getting one state to act against another, weaponizing internal association would be intended to have the enemy state attack itself. This may be a potent weapon if there was an enemy commander who posed a significant danger to the warfighting efforts of the perpetrating state, or an enemy scientist posed a similar danger to war efforts. Association can be weaponized to make the enemy state act against its own resources.

Imagine the development of the first nuclear weapon was ongoing in today’s world, with Oppenheimer still directing the Manhattan project in an effort to create a nuclear bomb. Now imagine that an enemy of the United States was able to launch cyber-attacks that hampered this effort. Moreover, that enemy was able to so strongly associate those attacks as having been launched by Oppenheimer himself that the United States considered him a threat to future development and an agent of a foreign enemy. This association means that not only was a cyber-attack launched against the nuclear bomb development program, but that successful or not, association was weaponized to convince the United States to depose their own most valuable resource in the development of a nuclear bomb, the lead scientist and director of the program in Oppenheimer. The association and subsequent actions against Oppenheimer would probably set the US nuclear program back further than even a successful cyber-attack effect.

Summary

In this chapter we covered the concept of association and how it is an unavoidable aspect of operations within the cyber domain. Through example scenarios involving cyber and non-cyber domains, the concept of association and routing of cyber traffic was illustrated. Incidental association and its impacts were covered as were different methods for purposeful association and the benefits and drawbacks to warfare, international convention, alliances, and state and individual livelihood.