Logical Attribution

The greatest challenge in identifying and responding to acts of war within the cyber domain is the extreme difficulty in determining the motive of that enemy activity. In fact, unless that activity is indisputably a cyber-attack effect, it cannot responsibly be considered an act of war regardless of who it is attributed to. Further, this chapter will reveal that even when cyber activity is positively a cyber-attack, unless the perpetrator outright declares themselves as the actor, attribution and identification of an enemy is unlikely. It is nearly impossible to attribute and identify with high enough fidelity that a declaration of war or warfighting responses within Title 10 authorities would be appropriate.

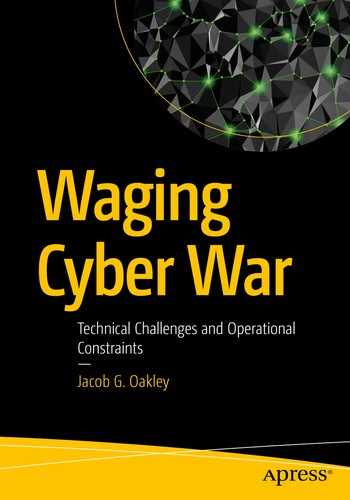

Logical Process of Attribution

- 1.

Discovering indicators of compromise

- 2.

Associating them together as belonging to specific actors based on their attributes

- 3.

Identification of the actor

- 4.

Determining the motive of the actor

The vast complexity involved in the technical aspects of attribution will be covered in later parts of this chapter, but it is initially necessary to understand the logical process of attribution as well as why attribution is carried out.

Discovery

In the discovery phase of the attribution process, artifacts and indicators, discovered within the organization that may point to the presence of an unauthorized activity, are identified. Indicators of compromise can be anything from obviously illegitimate actions or even suspiciously timed legitimate activity, and in building the complete picture of these indicators, both digital evidence from the cyber domain and physical clues must be considered as possible indicators. As such, sources that identify artifacts and other indicators of compromise can be as diverse as a user noticing their machine is running slower than normal, a person within the organization acting abnormal, or a piece of security software showing an alert. To illustrate how challenging, it can be at times to decipher if an occurrence is an indicator of compromise, imagine that for over a week the security systems across an organization had not a single alert. This too can be an indicator of compromise, especially if most weeks there are at least several alerts of one kind or another. In this example perhaps a malicious actor changed settings on security systems or manipulated their ability to detect activities they normally would.

Association

Association might be the most integral portion of the attribution process. I say this because if association is done incorrectly, it can make identification and discerning a motivation impossible or wildly inaccurate. Association is simply the grouping together of discovered indicators based on one or more attributes. Here, the great challenge is knowing what to associate and what not to associate. Imagine you have 100 indicators discovered within your organization. We simply went off the attribute of the organization targeted we could falsely interpret that all 100 indicators were associated with a singular actor. Similarly, all 100 indicators probably each have at least one attribute that sets them apart. This could be used to inaccurately decide that all 100 were from 100 different actors based on the time of occurrence down to the 10th of a second. Real indicators often have many attributes, and some will line up and others won’t. It is deciding which are more important, more reliable, and more likely to tie together indicators to a specific actor within the organization that drives good association of indicators into the picture of a unique actor and its actions.

Identification

With a set of indicators sufficiently tied to one actor within the organization, it is necessary to identify the likely culprit behind that activity. Some attributes of indicators can lend themselves to identifying potential actors whom are sources of the malicious activity. As an example, if the activity only ever occurs between certain hours, which aren’t normal business hours of the target organization, perhaps that reflects a normal work day for the perpetrator. Oftentimes one of the best identifying attributes for who the attacker might be is simply who the target is. Take, for instance, an attack on Indian government computers, even without identifying the remote source of the activity, one potentially leading candidate for malicious activity might be Pakistan simply based off the hostile relationship between the two countries. Identification takes as much finesse as appropriate association does and involves digital evidence, judgment, as well as intelligence and situational awareness of who may benefit from the type of activity tied to the actor.

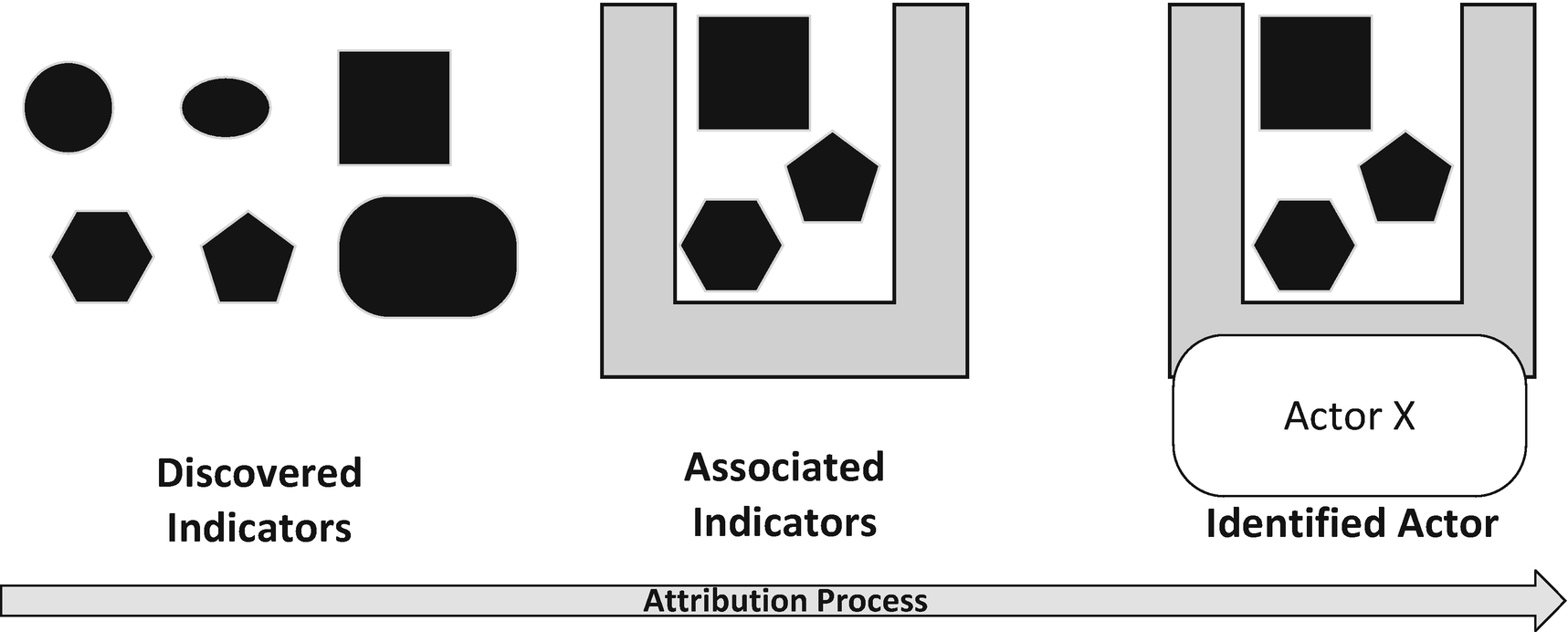

Motivation

Complete Attribution

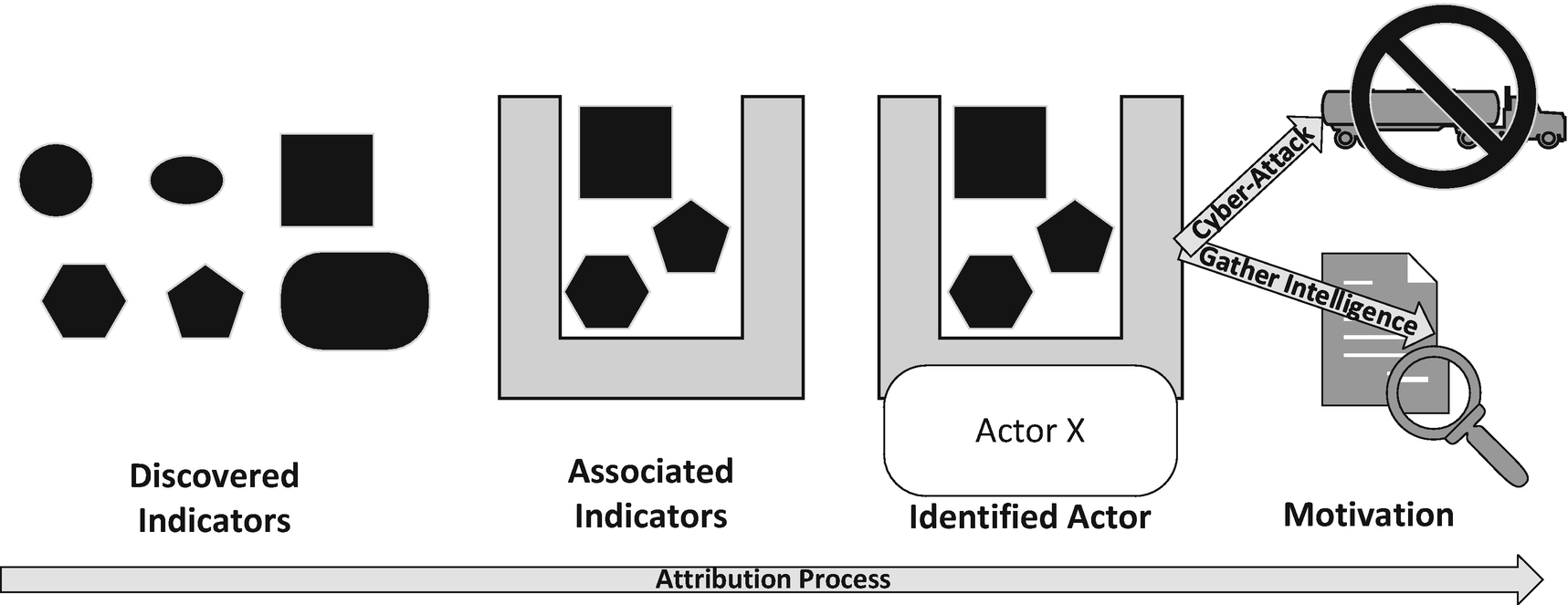

Post-attribution Process

Complete or partial attribution processes are used to derive what type response should be carried out. It is just as important to consider the completeness of the attribution process as it is to consider how reliably each step was carried out. If we carry out the attribution process to conclusion and have decided on both an identification and motivation, we may still be unable to act on that conclusion if the level of confidence is not high enough. On the other hand, if we are only able to perform association and can get no further in the process but have an extremely high level of confidence in our grouping of indicators with a specific actor, it can still lead to very specific response actions. Though this type of response may not be targeted without identification, it can still be just as important to the security of the target of malicious activity. This is especially the case when we consider state actions based on cyber domain activity and its ability to be attributed.

Is Active Response Itself Appropriate?

In a previous chapter, we discussed at length the trade-off between deciding to perform a cyber-attack or if it is perhaps more beneficial to continue to carry out intelligence gathering activities on a given target. This same consideration needs to be levied against any decision we base on attribution. In fact, when attribution results in identification and especially if motivation is determined, it might be wiser to not respond on that information. If an actor is determined to be within an organization, it can be more useful to continue to learn more about what the actor is doing and monitor their activity than kick them out, respond to their actions, or even publicly acknowledge their identity and activity within the network. As far as activity within the cyber domain goes, this non-response could be due to political implications or other non-technical, non-warfighting, or security reasons.

Active Responses

The decision on what to do based on the results of the attribution process are important, and they are more based on the motivation of the actor than its identification or indicator attributes. It is probably accurate to say that even a passive response still represents a reaction to discovered activity. Active responses do require an attributable identification and motivation, and thus, any attribution process that doesn’t reliably produce answers to these two phases cannot lead to an active response.

Attack Responses

Active response is extremely important and is fundamental in waging war in the cyber domain. To engage in active cyber domain responses though, the motivation of the actor within the organization or state must be known to be a cyber-attack. Beyond that, the identification of the perpetrator must also be completely known, if not openly acknowledged to lead to an active response. The attribution process is invaluable to this situation where without identity and motivation we cannot know who our enemy is nor how to target them with a response. More than simply driving the active attack response we imagine in warfighting within the cyber domain, identification and motivation can allow the victim state to understand at least a part of the attack methodology and goal of their attacker and thus take actions to better defend themselves.

Non-attack Responses

Responses

Attributes

The attributes of artifacts and indicators of compromise are innumerable in their diversity, so instead of trying to cover them all, we will discuss those that I think are more specific to malicious activity than anything else. The following are also some of the most appropriate attributes that should be used to tie discovered evidence to a specific actor. The attributes we will cover fall into the two broad categories of technical and tactical characteristics.

Technical Attributes

Technical attributes are those which characterize an indicator of compromise or artifact wholly within the cyber domain. The following are several important attributes likely to be associated with discovered evidence of unauthorized activity in a network or organization.

Exploit Tools

Now that you have an understanding of what is meant by exploitation within the cyber domain, I will elaborate a bit further into the technical aspects involved in exploitation to show some of the characteristics different exploit tools might have that can be used to tie them to, or differentiate them from, a known actor. Exploit tools are those weaponized vulnerabilities leveraged to manipulate a target system in an unauthorized way as well as the frameworks and tools that allow hackers to leverage them. By this I mean that a weaponized vulnerability is an exploit tool as is a framework which enables the throwing of such exploits, such as Metasploit or Cobalt Strike. Exploit tools used by the same actor may have many different markers which tie them together or with other types of attributes, but a list of some example exploit tool attributes in the following text might be used to determine whether or not discovered activity belongs to one actor or another.

Exploit tools have many technical characteristics and range widely in their likelihood to be specific to an actor. The vulnerability being leveraged, for instance, if it is a well-known remote code vulnerability, or even something like a misconfiguration, it is difficult to tie exploit tools together as one actor based just on that information. Well-known vulnerabilities are certainly weaponized by many actors, and misconfigurations can be leveraged by anyone who discovered them, so that would be an example of a potentially flawed characteristic to associate exploit tools on. On the other hand, if the vulnerability leveraged is completely unknown (also called a zero-day vulnerability) or it is leveraged in a novel way (zero-day exploit), it is likely a great way of attributing to a single actor.

Frameworks which through exploits can be good for identifying a signature to one actor or another. If multiple different remote code exploits have been discovered within the organization and all are using the same type of communication methodology, it might be a good way to tie to a specific actor. However, if the communication methodology always uses port 4444 for return calls from exploit payloads, and some quick open source research leads us to see that it is a default port for Metasploit. Being a free, publicly available exploit framework, basing actor attribution just on this could be folly as many different attackers (albeit less sophisticated ones) are liable to use this tool and forget or not care to change its default port from 4444.

Access Tools

Access tools are also known as backdoors, remote access tool kits (RATs), and implants, among other monikers. They all have a goal of retaining access to a given system. When used in preparation of a battlefield, this access is being maintained to return and deliver some attack effect at a later time. When being used for intelligence gathering, access tools are used to return to victim systems and continue to gather up-to-date information. In either case access tools often also enable attackers to come back to the installed device at will and use it to pivot deeper within organizations.

Of the many characteristics access tools may have, a subset of them likely to be considered for attribution purposes are the persistence mechanism and binary signatures such as its hash. Persistence, if present, is the way an access tool is set up to maintain its access to a system after reboot or even sometimes after systems are whipped and reinstalled. Just like the exploit tool characteristics, there are good and bad ways to use these attributes. For example, one way of persisting an access tool on a target system is using the built-in scheduler for that operating system. Whether using the “at” or “schtasks” commands on Windows or cron-type functionality on Linux, schedulers have been available in operating systems for decades and can be used for administrative and nefarious reasons all the same. Tying indicators together just because the scheduler of the system was used to re-execute the access tool every time the machine restarted is not a very good way of attributing them to an actor as this type of persistence is easily leveraged by any actor who has exploited or otherwise gained access to the system. If the access tool is persisted in a novel way or an extremely discrete and rarely seen technical fashion, it is likely a great way to associate access tools with a similar actor.

The access tool itself poses a potential attributable characteristic. If the access tool is discovered and sent off to one of many security vendors with signature databases and it comes back as Meterpreter, it is not a good differentiator. This is the default remote access toolkit that ships with the same Kali Linux operating system as the Metasploit exploit framework and for the same reasons could be used by any attacker. If the tool is extremely complex in its functionally, attempts to do something like delete itself upon investigation or simply comes back as never having been seen before based on its size name or other characteristics, it could be a good differentiator between one actor and others.

Attack Effects

Attack effects are interesting to consider for attributable characteristics. Here we essentially get to know the motivation of the attacker before finishing the process of attribution if the effect is obviously used for cyber-attack intent. That being said, it does not mean the perpetrator is attempting to wage cyber war just because there is an attack effect involved. I would like to reference the earlier example of Iranian hackers encrypting systems and demanding ransom to unlock them. Certainly, encrypting whole devices could be considered a cyber-attack especially if the victim device is a military or government system. Attributing an actor and then declaring war against that actor based on an attack effect like this would be similar to declaring war on Canada because some disgruntled hockey fans on the Canadian side of the border are throwing rocks at some US hockey fans on the US side and they accidently hit a border patrol vehicle.

If an attack effect like encrypting or simply deleting a target file system is not a very unique way of attacking a cyber target, it is not a great way to tie actions to an actor. Similarly, if the attack effect doesn’t contextually seem like it is likely to be a warfighting action, it is likely safe to assume that the perpetrator was not a warfighter acting on behalf of an enemy state. In such an example, even if attribution was complete, declaration of war is not necessarily the appropriate response as the question of state sponsorship is unanswered or not applicable. If the attack effect is complex, extremely specific, or obviously related to warfighting, it is a good indicator of compromise and probably requires active response if successfully attributed. An attack that encrypts hard drives and happens to effect military computers should not be considered a warfighting action, whereas an attack that takes over control of computers specific to military radar control systems is specific enough in its nature to tie to a unique actor and appropriate to consider active responses.

Redirection Points

I think redirection points are a great way of tying actions to a singular actor, but they are also terrible for use in identification and determining motivation phases of the attribution process. Redirection points are the locations of listening posts or pivot points where traffic from an access tool or exploit tool communicates to and/or from. These are great pieces of information to tie cyber domain activity together because they are tying traffic flows to a source, and that sort of communication channel is extremely unlikely to belong to multiple actors. This could be a location external to the organization, where the initial access tools are beaconing back to. If you, say, discovered one infected system talking out to a random address in Estonia and then you searched your network for logs of traffic talking to the same address, it is very likely those belong to the same actor. Similarly, within the network if you find an access tool communicating back to a specific user machine on a routine basis, and you search your network logs for that sort of communication and you find multiple other machines have been accessed and/or exploited from it, that would be a great attribute to tie actions together with. The actor probably gained access to the user device using malicious email phishing and then used it as a launch point to get deeper into the organization.

The reason redirection points are terrible to use in the identification of an actor or understanding motivation is due to their availability. I could go on any number of cloud hosting services such as Amazon’s AWS and, for free, turn on a server based in any number of countries across the world. If I used that server as the home base for my access tools, it isn’t really indicative at all of where I am physically sitting or what state is sponsoring my activity. In fact, if as an organization, state, or simply network you see that a tremendous amount of traffic is hitting your firewall from one location or another, it is probably more appropriate to wonder why attackers are using that location to redirect from than to wonder why that location’s people are attacking you.

Time

As far as technical attributes go, time is being considered for its association among discovered indicators and artifacts. We will also discuss the tactically applicable indicator of time as well in a later section. When available as a discovered indicator, the attribute of time can be valuable on systems. If you had an alert caused by a security software that said it stopped unauthorized activity, and you then searched your system for events within a few minutes of that time, it might lead you to other suspicious activities. As you find more activities and expand the time window you search in, it may reveal a whole host of indicators that are tied to the activity of a singular actor on the system.

Obviously, time can’t be the only tie-in, as systems are often very busy and have many events logged. However, if the alert was only a second later than an error event that referenced a file which was only introduced to the system a minute earlier, and logs show a user authenticated from a remote system and moved it to yours, it’s fair to say they are probably the same actor’s story of actions on your system. In this way time stamps can be used to both discover additional related activity and tie them to the same actor. Much like the redirection point attribute though, time is mostly useful for tying activities together based on proximity of time stamps to each other.

Tactical Attributes

Tactical attributes are those which while discovered through activity within the cyber domain actually apply more to the actual individuals carrying out that activity.

Timing

We will pick up right where we left off by referencing timing again. Technically speaking we were considering the attribute of time stamping of system events as a way to characterize and activity as belonging to an actor. Tactically speaking we would focus more on the window of time. This attribute is best used when evaluating a large set of indicators across long periods of discovery. Over the course of weeks or even months if cyber domain activity was identified within an organization but fidelity of the attributes was not enough to associate them as a singular actor, timing of operations can be used to do so. Say, for instance, activity over the past months only occurred between 2 PM local and 10 PM local and for seemingly no reason. It could be that 2 PM and 10 PM local for the victim were something like 9 AM and 5 PM local to the actor. Seemingly disparate indicators of compromise that continue to happen over long periods of time and within the same period of time we will consider to be an operational window can allow for those activities to be grouped together.

Targets

As mentioned earlier in this chapter, the target itself can be an indicator if activities belong to the same cyber domain actor. Leveraging this characteristic of an indicator is also extremely fidelity constrained. Take the US military for instance; targeting of the US military by a cyber domain activity could probably be associated with well over 100 other nation states, not to mention actors independent of state-sponsored motivations. Even a specific base or service or unit is probably not enough to reliably use as a tying attribute to associate activities with an actor. At this level of fidelity, the target can certainly narrow down activities to actors from a smaller subset of possibilities.

For instance, if the target of a cyber activity was US PACOM (Pacific Command), we might say that likely actors would be from Asian countries aggressive to the United States such as China or North Korea. I stress that such target fidelity should only be used to narrow down between actors or as a supporting characterization for attribution. If the target was a specific commander or government agent, say, commander of the US forces in South Korea, or ambassador to South Korea, it becomes a bit safer to rely on such indicators as attributing to specific actors and even their identities. Another interesting way of leveraging indicators of compromise to identify perpetrators is in widespread activities.

Many security companies who do reports of large attack activities map out the number of infected hosts by country. If an attack had, say, 90% of its affected end points in areas of countries with Kurdish populations, it might be understandably deductive to associate that activity with a country who considers the Kurds a threat, such as Turkey. This type of characteristic used in this way also can cast a wider net of possibilities. Say a cyber activity has many different countries infected, but over 90% are all within a country like Russia. Since many countries probably have espionage and intelligence gathering efforts against Russia, it might narrow down the perpetrator identity to a subset of state sponsorships, but it would still be a large pool of potential actors and therefore not necessarily great for attribution.

Sophistication

Sophistication is a tricky characteristic to utilize as it requires much technical understanding of offensive cyber operations within the cyber domain as well as how enemies are likely to target your organization. This difficulty though does not impact its value when correctly applied in analysis of indicators and artifacts. There are several sophistication-specific attributes we would look to discern about various indicators when using sophistication markers to tie activities together and to actors.

First there is sophistication of the attack indicated. This is not a technical characteristic but a tradecraft one. Regardless of whether the attack used advanced and complex tools or open source and readily available operating system functionalities to accomplish compromise, we are looking at the strategy of the attack. Well-known tools and techniques can be used but combined in extremely creative and effective ways to achieve compromise goals in the cyber domain. If indicators and artifacts gathered over the course of months or years point to an extremely creative and adaptable adversary that might allow for tying seemingly diverse technical capabilities together as being from one specific actor.

Conversely, very advanced tools can be used in very simplistic efforts and also indicate a unique and specific actor was involved. Recently, more than one advanced and technically sophisticated exploitation tools have been leaked on the internet and seemingly were created with state sponsorship simply based on the effort involved in their inherent sophistication. Those tools and exploits have then been used in all manner of attacks by amateur hackers and professional criminals alike. In this situation the advanced sophistication that was involved in the technical aspects of the tool were not indicative of a unique actor, but the blunt application of the sophisticated tool might be.

The last facet of sophistication in cyber activity I would like to point out for inclusion in attribution efforts is that of conscious attempts to avoid attribution. This is the hallmark of an advanced threat, and the method of detection avoidance and the regularity of it can certainly pair with other characteristics of indicators to associate activity with specific actors. This is true of extremely careful actors who clean up after themselves and hide in baseline noise of organizations as well as those who have no care for such efforts. Some adversaries can be attributed by their distinct lack of discipline or even uncaring attitude toward being identified or called out by an attribution process.

Forget Everything You Thought You Knew

We have already covered how both technical and tactical attributes used to associate activity with actors can be within themselves very accurate and frustratingly unreliable. Unfortunately, even with good characterization of technical and tactical attributes used for associated activity, there is a mountain of uncertainty between those data points and a complete and appropriate attribution process. That is because nearly every single artifact or indicator of compromise in the cyber domain can have been altered, fabricated, or even be a false positive, and there is similarly almost no way of detecting if it was tampered with depending on the situation.

I mentioned how the port 4444 on return traffic communicating to an exploit framework was indicative of using Metasploit or Meterpreter. Any attack framework and any exploit payload could also be configured to do the same. An attacker might do this out of chance, picking 4444 not thinking it will associate them with an open source tool. They also may be doing it on purpose to make investigators think they are an amateur hacker and not a state-sponsored intelligence gathering activity within the cyber domain. Access tools might utilize a persistence mechanism known to be associated with a particular well-acknowledged actor. This might be because it was the only thing available to persist the access tool and the actor took a chance it might not get caught. It could also be because the actor is going to conduct a cyber-attack activity and wants to frame the well-acknowledged group to hopefully steer investigations and responses away from itself.

Time stamps on files and in logs can be changed, edited, or deleted in almost every case if the actor has sufficient context on the system via exploitation. This can make activity look benign or simply make it very difficult to associate together or to an actor. Actors could also conduct their operations on the same schedule as typical work days local to the target systems and state, this avoiding connection to their possible location via operational Windows. A nation state could infect machines in its own cyberspace with the same tools used to attack enemy assets. This way if the activity were discovered and the tools signature by antivirus companies, the subsequent reports would show heat maps with potentially even more compromises in the aggressing country than the victim country. That would certainly throw off reliable attribution and make any sort of non-cyber domain warfighting response to a cyber-attack action seem unprovoked and unacceptable.

Lastly much like the port usage making some other tool appear to communicate like the open source Metasploit and Meterpreter, actors could simply leverage those open source tools themselves. Sophistication is only reliable as an attribute if the actor themselves is actively trying to appear less sophisticated than they are capable of to avoid deduction that the activity they are conducting is associated with a nation state.

Unsteady Foundation

Though these recent revelations may make complete attribution seem rather hopeless, there is one way to try and determine how reliable a given indicator or artifact may be. If the sophistication of an attacker is likely known due to some otherwise provided intelligence or a likely identification of the actor perpetrating the activity, we have room for some deduction. Say I know the actor likely targeting me is not one who is very sneaky or careful or cares about being attributed. In this case I can tentatively assume that when I discover indicators and artifacts, it is not likely they were altered, at least not by the actor I assume to be targeting me. All you can essentially do at this point is say whether or not the indicator is likely tied to an uncaring and probable careless actor or it is potentially evidence of a more sophisticated cyber activity.

Aside from the ability of attributes to be altered, and this can impact the attribution process, there is also a concept of reliability and fidelity to attributes in general. For each attribute used to create an actor profile or potentially characteristics that tie indicators together and to actors, there must be other considerations as well.

I can think of one great example for this. Imagine you discover some activity within your organization, and you tie much of it to a singular actor who has been using a well-known vulnerability and exploit incorporated into an open source exploitation framework. You should have already patched or removed vulnerable systems, but it just wasn’t a huge priority and the portion of the organization these activities were found in were not of much consequence, so you assume it is some amateur hacker and not likely a state-sponsored activity that warrants more dire responses. However, upon further attempts at correlating indicators of compromise and artifacts within your network, you realize that the same access tool installed after the exploit was used on the initially discovered machines is actually present on many systems in more crucial and sensitive areas of the organization. Upon investigating those systems, you determine that the access tool has been present on them for over 5 years and that the same exploit was used to gain access. You look at the information online for the well-known exploit and vulnerability and read that it was only publicly known starting 4 years ago. Now the picture is much different; now it seems you were the target of likely state-sponsored cyber activities which leveraged at the time, zero-day exploits; and worse, this actor has been active in your network over the course of half a decade.

Summary

In this chapter we covered the logical process of attribution involved in cyber domain activities and their perpetrating actors. We discussed the different types of responses to attributed activity and the level of attribution required to justify them. We covered characteristics of indicators of compromise and artifacts that are indicative of malicious cyber activities. We covered where they were both appropriate and inappropriate at associating activities with actors as well as how easily they were altered.

The goal of this chapter was to educate the reader on just how unrealistic it is to expect the attribution process to end with identification of the actor and an understanding of motivation. This is not even considering that most compromises go unnoticed for months or years, and even if attribution was complete, it is probably not timely. Given these now known factors in cyber warfare, you should understand that timely active response to cyber activity is an irresponsible expectation and action. Even if a cyber domain activity led to a cyber-attack effect that was immediately detected, the attribution process would not allow for anything resembling a real-time return of fire which is what the warfighter expects and has learned to rely on. We must therefore accept both the lack of appropriateness in the return fire concept within cyber warfare and its inherent technical and tactical difficulties. Essentially, short of an activity being positively admitted as a cyber-attack effect openly acknowledged by a state government as a warfighting action, there won’t be responsible or reliable recompense. Attempting to perform return fire activities within cyber, land, air, sea, or space domains without this type of open acknowledgment is a fool’s errand and likely to be interpreted by outside observers as unprovoked and reckless. As such, it would violate some if not all of the previously discussed political and legal constraints to waging a cyber war.