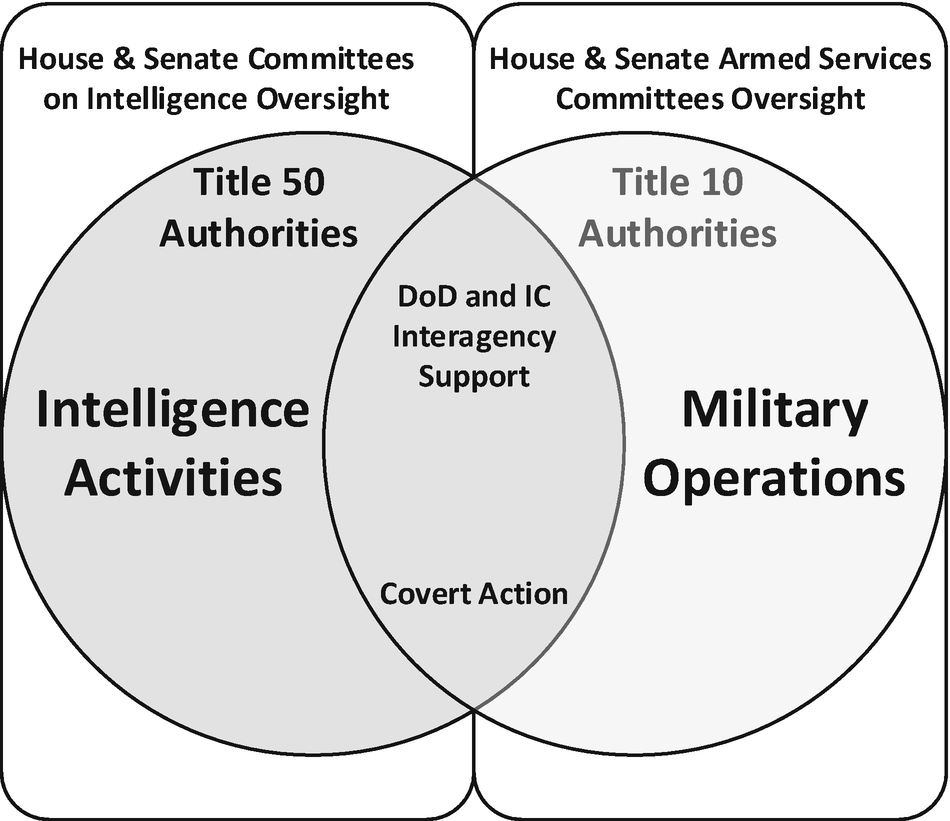

Title 10 and Title 50 of the US Code are legal documents that outline the responsibilities of the Department of Defense (DoD) and Intelligence Community (IC), respectively. These two documents—with regard to war itself and cyber warfare specifically—are often poorly understood, misrepresented, and incorrectly cited. The intense interest and scrutiny in these documents is related to the legal authority they endow and the manner and responsibility for oversight of actions within that authority. I will do my best to efficiently summarize the importance of these documents to the warfighter and to cyber warfare itself as well as covering a third type of activity in covert action. I will also attempt to establish a fairly reliable line where activity must be done in the constraints of one title or another. I will further discuss examples of how this affects technical aspects of cyber warfare.

Title 50—Intelligence Community

For the sake of easier explanation and understanding of examples later, I will discuss Title 50 first. As was mentioned earlier, Title 50 outlines roles and responsibilities and authorities for the Intelligence Community. Title 50 is actually labeled as “War and National Defense” and has many chapters within it covering many topics. These chapters are as varied as espionage, the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), and the National Security Agency (NSA), to those dealing with Merchant Ship Sales, Helium, Absentee Voting, and Wind Tunnels. For the purposes of this book though, we will focus on its direction and authority to the Intelligence Community for its activities under Title 50 and the Intelligence Committee oversight of those activities. In fact, much of the focus on discerning the difference between Title 50 and Title 10 actions is due to Intelligence Committees insisting it has oversight on the correct application of authority, actions within that authority, and budgetary oversight over Title 50 actions and often misunderstanding or perhaps purposefully attempting to paint Title 10 activities as falling under their Title 50 purview.

The fact is that with intelligence activities there is no delimiting line that separates those which may be done under Title 50 or Title 10. The exact same information gathering activity could be performed under either title and still be completely above board and legal. The Secretary of Defense, for instance, has roles and authority to collect intelligence both under Title 50 and Title 10 legalities. In fact, Executive Order (EO) 12333 asserts this by directing that the Secretary of Defense be responsible for collecting intelligence for his Department of Defense as well as the Intelligence Community. Many members of the Intelligence Community are within the DoD such as the armed services (USA, USN, USAF, USMC), CIA, NSA, and NRO, while department members of the IC are not, such as Department of Energy (DoE), Department of Homeland Security (DHS), and Department of State (DoS).

Breakdown of Intelligence Community

Title 10—Department of Defense

Among other things Title 10 actually outlines things like the uniformed code of military justice (UCMJ), as well as the establishment of the Departments of the Navy, Army, and Air Force. More relevantly to our discussions, it outlines roles and responsibilities of the Secretary of Defense (and the Commander in Chief through him) to conduct military activities. Therefore, the authority to conduct Title 10 activities is established as the Secretary of Defense and Commander in Chief, and the oversight for such activities is the responsibility of House and Senate Armed Services Committees. It is also important to understand that even though Title 10 activities are done with authority from the DoD, there is still a requirement for approval from Congress for the country to go to war. As such Title 10 activities of the DoD carried out against another state or otherwise declared enemy should require the same.

Interestingly, the Commander in Chief is allowed to deploy DoD assets on his or her own authority and discretion alone as long as Congress is notified within a 48-hour period. There is then a 60-day period where Congress must approve the action; otherwise, the activity must stop. These rules apply as much to cyber warfare under Title 10 as they do the deployment of troops. Something to consider here though is that at the end of 60 days, troops can be pulled back from a deployment or occupation. A missile battery can cease striking a target at the end of this same period even if the damage cannot be undone. The problem with certain aspects and tools within the cyber warfare realm is that at the end of 60 days there is in many cases no way to guarantee that a worm- or virus-type implement of war will stop performing its action. Such a tool may go on attacking systems of the target, or worse yet, bystanders and innocents, long after the 60-day period, and if Congress decides not to approve the action, then what?

Maintaining Military Operations

Congressional and House Intelligence Committees have in many cases asserted that it should have oversight of activities done under Title 10 via their intelligence oversight committees. This is especially true of cyber warfare given that it is conducted in secret and in places where public knowledge of such actions could raise both diplomatic and national security concerns. This contetion is understandable; however, the law outlines that as long as several requirements are maintained throughout the operation, it still falls within the boundaries of a Title 10 action. Cyber warfare activities are military actions by the DoD under Title 10 and not Title 50 actions of the IC so long as they remain under the control of a military commander and are performed before or during an actual or even anticipated military operation.

Must be conducted by US military personnel.

Those personnel must be under command and control authority of a military commander.

Activities must be either before or during ongoing or expected hostility where US military forces are involved.

The role of the US military in that activity is obvious or will eventually be acknowledged publicly.

The first three were essentially already covered; however, the last one, that the role of the US military must eventually be admitted or obviously understood, is very interesting with regard to cyber warfare. Take the raid that killed Osama bin Laden, which was performed by military personnel in another sovereign country and without a declaration of war by Congress. This was done under Title 10 authority, and the reason it did not need approval from Congress is that the Commander in Chief at the time, Barack Obama, asserted his authority over the Department of Defense to order it and reported to Congress and in fact the world within 48 hours. The operation was already over so there was no need for Congress to even approve it within the 60-day window; also the raid was a Title 10 military operation and not a covert action, which we will cover later, due to the fact that the US military personnel role in it was acknowledged.

But hold on, the US DoD as well as IC devoted years of effort toward finding Osama bin Laden, how is it that the 60-day period was not long overdrawn? The answer is simply that many of the activities pre-dating the actual raid itself were carried out under Title 50 by the Intelligence Community. Where the waters get muddy for some with Title 10 and Title 50 here is the third item in the previous list which stated traditional military activities can be either before or during ongoing or expected operations involving military personnel. A type of activity that falls within the scope of this state is something called battlefield preparation, where under Title 10 authority, the DoD can do things like conduct reconnaissance, gather intelligence, and perform other actions of unconventional warfare which seemingly fall under Title 50 authorities as long as they are preparing the battlefield for conventional forces.

When we look at cyber activities that may relate to such a raid, we can clearly outline what falls under Title 50 and the oversight of Intelligence Committees and which does not. Most of the activity in the years, months, and even weeks prior to the raid in Pakistan are certainly within the realm of Title 50 authority and oversight. Intelligence was gathered, surveillance was conducted, and many other actions taken by the Intelligence Community. These activities can just as easily be performed within the domain of cyber, involving computer exploitation, as much as they can from space with satellites or in the air with drones and aircraft.

So, a computer that is attacked and taken over to perform surveillance of a target who may eventually be related to the raid is considered Title 50 and requires no special notification or approval from Congress. If cyber warfare is used to exploit computers that control communication systems or power systems with the intent of denying the enemy those resources once the operation began, it would fall under Title 10. These actions would be performed to prepare the battlefield for the Navy SEALs who performed the raid and would have to fall within that 48-hour notification and 60-day approval period as being traditional military activity.

Covert Action

An activity of the US government.

Aimed at influencing political, economic, or military situations abroad.

The role of the United States will not be obvious or ever acknowledged openly.

Activities with the primary goal of intelligence collection

Activities with the primary goal of counterintelligence

Traditional activities that are to better or maintain operational security of government programs or administrative activities

Traditional diplomatic or military activities or their routine support

Traditional law enforcement activities carried out by US law enforcement agencies or their routine support

Activity that provides routine support to an overt activity

Oversight and Activity Breakdown

Bringing It Together

This has been a lot of policy and law that originally had nothing to do with cyber which is needed to understand the truly unique challenge it poses as a warfighting domain, a type of warfare, and a warfighting implement. Let’s say another state discovers that their government and military computer systems have been infected by cyber tools such as virus or worm. Next, we will assume that by some extremely rare circumstance that state has reliably attributed that action to be done by the US military. In such a situation, that country would have no efficient way of knowing whether that computer was infected in an attempt to gather intelligence under Title 50 or to conduct military operations under Title 10. This creates an extremely precarious situation where a foreign government might choose to respond to an act of cyber-enabled intelligence gathering thinking that it was instead an act of cyber warfare because it could be nearly impossible to discern to which the activity was related.

Conversely, the United States itself would often be unable to determine whether or not the computer hacking attempts of other states were acts of war or intelligence gathering, assuming attribution somehow happened as well. As you can now see, it becomes extremely important where we draw the line between cyber-enabled intelligence gathering under Title 50 and cyber warfare under Title 10 as this will dictate how we respond as a nation to perceived cyber aggressions and how we avoid misrepresenting our intentions to foreign adversaries.

Known US Responses

We do not know the true extent of the US response to warfighting and other less belligerent but no less malicious activities within the cyber domain. It is likely facets of the response capabilities available to the National Security Agency (NSA) and US Cyber Command (CYBERCOM) will never see the light of day in an unclassified venue. This is obviously in the interest of national security and our ability to defend ourselves in the cyber domain. We do have several examples though of how the US federal government holistically responds to certain cyber threats, and it is at least worth noting how this is done and having a quick discussion on its ability to deter foreign actors.

Generally speaking, the only US responses to cyber activity we know about publicly are from various media, and government reporting on the indictment and may involve the charging of foreign actors involved in cyber domain activities. We will cover a multitude of different examples of what we would consider not Title 10 activities if the United States was conducting them. These activities were carried out against the United States in two rough categories of espionage and action that could be analogous to cyber warfighting activity. The participants in this activity are also far ranging in their implied relationship to state actions. It is also important to keep in mind while reading these examples that in none of these cases did a state government acknowledge the activity.

Example 1

The first example is an indictment of Chinese intelligence officers and their recruited hackers by US prosecutors in October of 2018. This is a very straightforward example of the type of activity that would be considered Title 50. There was a state-sponsored entity conducting intelligence gathering in efforts to steal sensitive but commercial aviation and technological data over the course of multiple years. The response by the United States upon attributing the activity to individuals was to charge both the members of the Chinese Ministry of Security as well as the apparent Chinese civilians they recruited to do the work.

Example 2

The second example is an indictment of two Chinese nationals by US prosecutors in December 2018. The attackers are attributed to hacking efforts against US government agencies and corporations which included the Navy and NASA. The attackers were said to be working for the Chinese spy agency, the Chinese Ministry of State Security. The activity is assumed to be something closely resembling what may be considered Title 50 actions as they were gathering information from agencies and corporations involved in aviation, space, and satellite technology. Since some of the targets involved were specific to the US Navy the cyber activity could potentially be perceived as battlefield preparation for a later kinetic or cyber attack against the US Navy by an aggressor state. If that was deemed the case, it could be then considered more like a Title 10 activity and a potential act of war in the cyber domain. Remember, there is essentially no way to differentiate between intelligence gathering for foreign intelligence efforts and cyber activity being conducted to prepare a battlespace.

Example 3

The third example is the only one we will discuss where the actual hackers themselves are attributed and identified as being uniformed members of a foreign state. The US prosecutors indicted five Chinese military hackers for cyber espionage against US corporations for commercial advantage. Here I think it is important to note that the charges filed were specific in the nature of the attack as being espionage and for commercial advantage and not related to anything that might be considered Title 10–type activity. Imagine a situation where it was military-uniformed hackers perpetrating activity like that in Example 2. There it might be a bit harder to argue against preparing the battlefield motive, and in that case, it could be even more easily considered a Title 10–type activity and therefore cyber warfare.

Example 4

The last example we will cover is one which has an end effect which could be most analogous to what a cyber war attack would look like but which has none of the other trappings required to be labeled or perceived as such. Iranian civilians without any connection to government or military assets of Iran were indicted by US prosecutors for deploying ransomware that affected many systems inside the United States by encrypting their files and not giving access back to the system owner unless a ransom is paid. Clearly this is not a warfighting activity as it was an orchestrated extortion scheme that lasted years and made hundreds of thousands of dollars. Where it does resemble cyber warfare is in the end effect. An activity in the cyber domain had effects which stretched into other warfighting domains. Targets of these attacks were government agencies, random companies, and also networks such as those belonging to hospitals. In fact, several hospitals were forced to close and turn away patients. Imagine if such an attack was in fact perpetrated by a uniformed member of a foreign government. It would almost certainly constitute a cyber warfare attack, and if it was heinous enough in its end effect, resulting in purposeful widespread loss of life, there is a chance such an attack could result in a declaration of war. If not that it is likely to invoke similar Title 10–like activity by the United States if the perpetrating state could be satisfactorily attributed and named.

Other types of activity in this category may have already occurred and either not been disclosed (or perhaps DoJ response is not what is used) or we have not noticed.

How does this impact our own actions? Imagine a foreign nation calling out the specific name of a uniformed military member who is operating within legal and operational authority and just war philosophy and international laws of warfare. What are the implications here, how do they factor in? Is this type of activity only okay when we are not in open declared war such as the simmering activities between the United States and Iran or China for instance?

We know two facts regarding the US response to cyber activity potentially related to other nation states. First, the US response to activity that does not resemble Title 10 activity, and thus is not considered cyber warfighting activity in the cyber domain, is addressed through indictment by the US Department of Justice. This is a response similar to what happens when foreign spies are identified within our borders, where they are indicted and arrested if found. The second fact of this response method is that it does little to deter foreign actors. In-person Title 50–like behavior within US borders means perpetrators risk capture. Cyber Title 50–like behavior by our enemies has little to no result on the perpetrator even when attributed by name.

As for the activity not represented in these examples, actual cyber warfighting activities perceived by the United States to be Title 10 type, we have no known responses by the US government. This either means that such actions are responded to in a way outside of DoJ indictment or that we have yet to undergo such attacks. Given the brazen activity such as that perpetrated by the Chinese, Russian, and Iranian state-sponsored actors, it seems that more likely than not these actions have been conducted against US targets, potentially attributed and responded to outside of the public eye.

The concerning point in all of this to me is that if other states react the same way the United States does upon attributing Title 50–like activity, we have risks to those serving our country in the uniformed services and greater Intelligence Community . Imagine being a member in the intelligence gathering apparatus of the United States as a young enlisted person and being asked as part of your legally ordered duties to collect intelligence on foreign nations. Then imagine that nation somehow attributed that activity to you and put your face and name on international news outlets indicting you for the crimes. You are now unable to travel internationally for fear of being arrested by countries or agents aligned to the charging state.

Often the perception on this indictment response is that it is essentially meaningless as a deterrent and often more symbolic than effective. However, when we turn the table and look at it as the United States is a perpetrator, we suddenly feel a sensitivity to the indictment of uniformed members following orders. There is a distinct difference between agents recruited and compensated by a state intelligence apparatus that willingly conduct Title 50–related cyber actions and those who are doing so as part of their obligated military duty. This is not necessarily directly tied to cyber warfare actions which this book addresses in whole, but I feel it is something worth pondering as we walk through the different implications in state-sponsored activity in the cyber domain, warfighting and otherwise.

Espionage

Because some of the examples covered previously mention espionage questions about where it fits in with Title 10 and Title 50, cyber warfare and intelligence gathering are certain to come up. I will do my best to cover this topic although it exists in an extremely undefined space with regard to legality and authority, especially in how the United States authorizes its agents to conduct espionage.

Defining Espionage

Merriam-Webster defines espionage as “the practice of spying or using spies to obtain information about the plans and activities especially of a foreign government or a competing company.” To try and set apart this spying from what we have already established as information gathering we need to hone in on the mention of using spies. In my mind the difference between intelligence gathering under the authority that comes from Title 10 and Title 50 is that the perpetrator of that intelligence gathering is not a member of the state entity who wants the information.

This is not always the case, even just based on known espionage cases the United States has convened in court, but for the sake of differentiating espionage from intelligence gathering it is where I will draw the line. When the agent collecting information is a member of a state government or military and acting on that state’s behalf, it should be considered as intelligence gathering for either Title 10– or Title 50–like efforts. When the agent collecting information is not a member of the collecting state but is recruited by members of the collecting state, they are considered to be performing espionage. Again, this is not a formal legal definition, but it is where I think a logical separation between the two and between the authorities lies.

Title 18

As the United States entered World War I, it established US Code Title 18, Chapter 37, to define espionage, likely in an attempt to prevent US citizens from breaking the henceforth established law to help enemies against the US government. The main focus of the articles under Title 18, Chapter 37, are in regard to activity where the individual is purposefully obtaining information about US national defense knowing that the information collected will be likely used to injure the United States in some way. Some articles cover protecting people perpetrating such acts and call out more specifics, but that is the overall gist of it.

So here we have a US law focusing on persons in the United States clearly outlining what we consider espionage. I believe it lends itself to the definition we covered previously. Transposing the two we essentially arrive at espionage is gathering defense information with the intent to injure the security apparatus of a state where the person collecting the information is within the state to be injured and the interested party in the conduct of the espionage an external state. One other interesting thing about espionage is that it is not always sponsored or recruited by the enemy state. In fact, in many cases of espionage in the United States, the person collecting information and passing it along to foreign powers did so of their own volition, sometimes out of spite and sometimes out of assumed financial reparation and for other philosophical and ethical motivations.

Cyber and Espionage

Where the activities covered by Title 10 and Title 50 have their own special applications in regard to the cyber realm and where authorities lie, in espionage this is not the case. Since the person perpetrating espionage is typically not a member of the state which will use that information to injure the target it is gathered against, trying to apply authority to it is not really useful. It would actually put the perpetrator in an awkward spot if it had defined legal authority for members of foreign states to act as agents on its behalf by conducting espionage. Further, espionage applies, as we said to the persons doing the spying. That spying may be conducted with a camera, notes, USB drive, computer hacking, or any number of tools. The tools and methods and domains used to conduct espionage do not affect the authority it is done through because it is ultimately considered to be not specifically authorized by law.

Summary

In this chapter we covered the legal authorities established by US Code that define the lines of conduct and who is responsible for the carrying out of given activities and who is responsible for their oversight. We have framed cyber warfighting and activity in the cyber domain under these laws so that we understand how they dictate the way in which cyber warfare may be carried out. This information also brought us to the powerful conclusion that apart from other methods of warfighting, the cyber domain makes it inherently difficult to distinguish whether an activity’s motivation is related to warfighting or intelligence gathering. Lastly, we covered how the United States has officially responded to various activities by foreign agents in the cyber domain, noted the lack of any warfighting examples and discussed how espionage differs from authorized activity under US Code.