Chapter 9. Service Design Process and Management

Understand, plan, and manage the adaptive and iterative activities of service design.

Expert comments by:

Simon Clatworthy | Jamin Hegeman | Julia Jonas | Kathrin Möslein | Giovanni Ruello | Francesca Terzi | Christof Zürn

9.1 Understanding the service design process: A fast-forward example

9.2 Planning for a service design process

This chapter also includes

Managing Iterations

In this chapter, we’ll take an in-depth look at how the core activities of service design – research, ideation, prototyping, and implementation – can be planned and managed as an iterative service design process that fits your project, your stakeholders, and your team. Here are a few familiar points from Chapter 4, The core activities of service design, to keep in mind:

→ Make sure you solve the right problem before solving the problem right: Always challenge your initial assumptions. This is what sets design approaches apart: rather than jumping right in – which also often leads to obvious solutions – you first take a step back. You make sure you identify and understand the right problem before you move on to solutions. 1

→ Think in diamonds: Divergent and convergent thinking and doing are key when managing a service design process. Which of the activities or methods you use are divergent or convergent? What is the required mindset in terms of divergent and convergent thinking? Which mode should you be in just now? 2

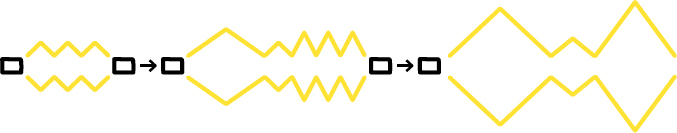

→ Iterate and adapt: The service design process is never a linear process. In fact, it’s quite the opposite. A service design process always needs to be explorative and iterative. You have to adapt to what you learn along the way, building on a series of more or less repeating, deepening, explorative loops: iterations. Practically, this means creating a rhythm of planning, doing, reflecting, then re-planning. 3

→ Look beyond the individual tools and methods: The service design process is more than a simple combination of its individual parts. Continuously reflect: How do the individual activities play together? How does the quality of the output of one activity affect the following activities? How can you build an overarching project structure that creates trust in the process but also creates predictability for your organization without giving up on the iterative and explorative principles? 4

→ Now, build your own: This is a process framework, not a step-by-step checklist. We challenge you to build your own customized service design process and give it a go. And we also challenge you to stay critical of your own process. Always ask yourself: What worked? What didn’t work? Why didn’t it work? How might we do it better next time? 5

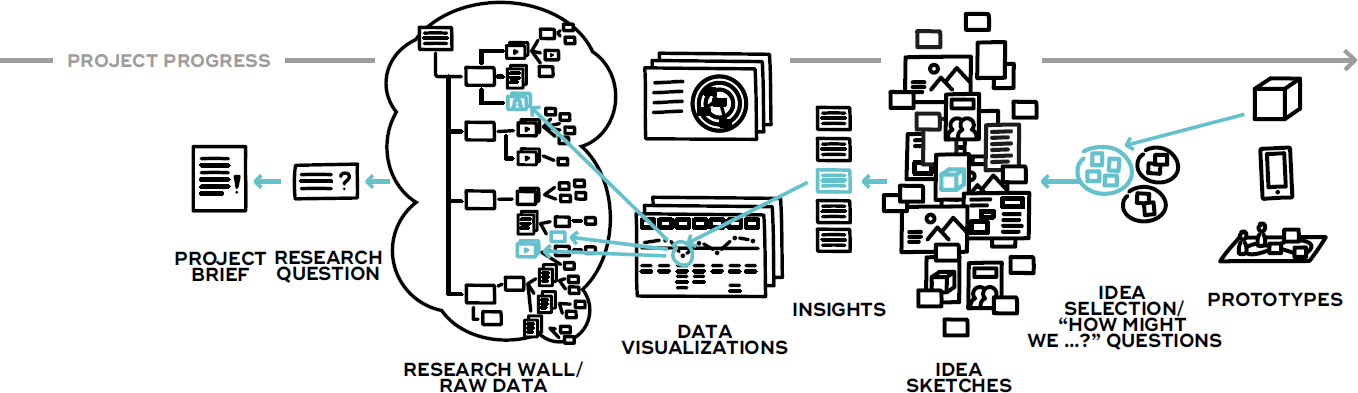

Understanding the Service Design Process: a Fast-Forward Example

Let’s revisit the core service design activities in a short exemplary walkthrough to get a better feel for how they connect and work together. Imagine you have discovered that the customer experience feedback rating (insert your favorite KPI here) of your business unit has dropped substantially. Your boss is worried and triggers a project within your organization to address the issue, and you decide to use a service design approach to tackle the project. Here is one path you might take.

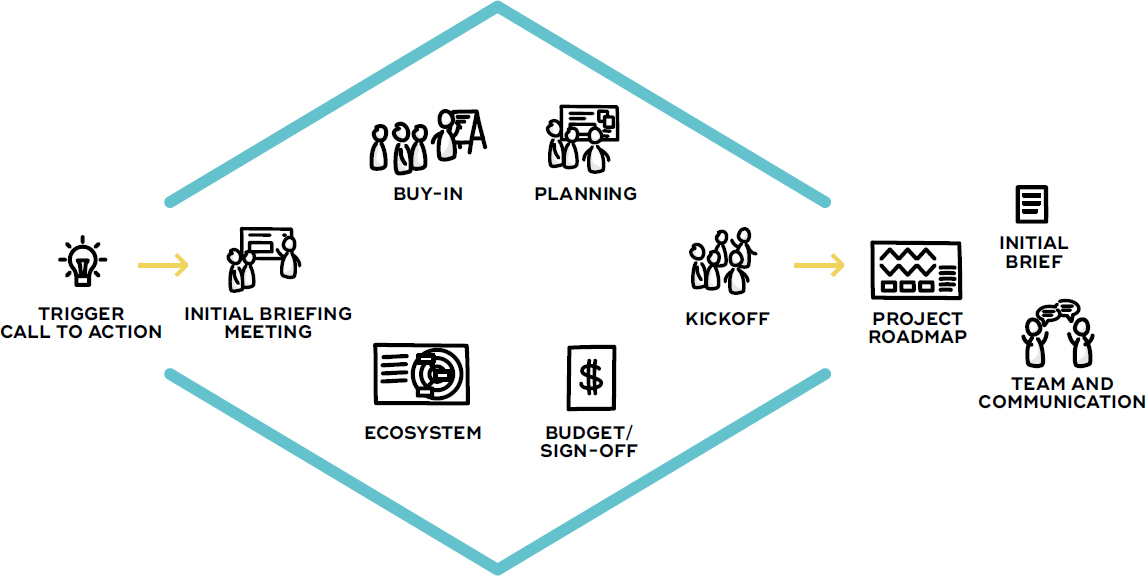

Planning and preparation

To get started, you put together a rationale for why you have chosen service design. 6 You find a suitable management sponsor and a great team, securing you the necessary organizational support and management buy-in. 7 After a careful inquiry and analysis of the project stakeholders and the wider ecosystem 8 and their expectations for the project, you start planning a service design process 9 for them as well as for your core project team, adapting the approach to the context and the realities of your people, organization, and industry. You put in place an initial management and communication structure to navigate and manage the service design process 10 on a daily basis and then officially kick off the project. You are now ready to dive into the content work.

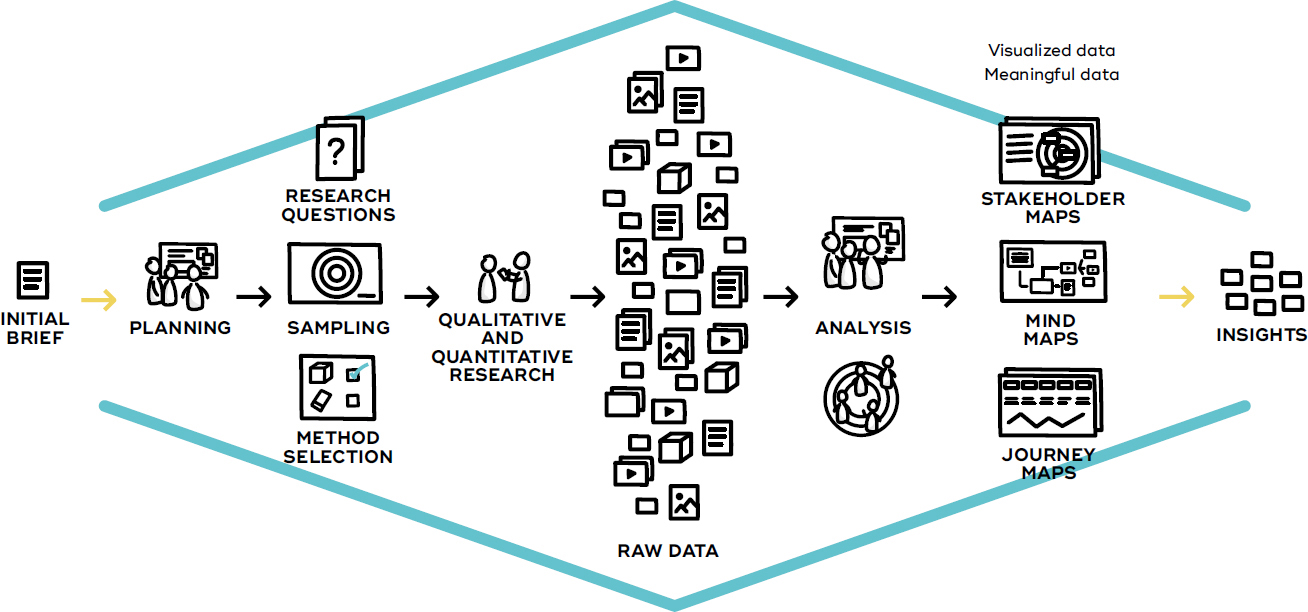

Research 11

Your first challenge is that the change in your feedback rating by itself does not tell you why it went wrong. So clearly, you need to look deeper, beyond the numbers. You ask yourself: What do I need to learn? What do I need to find out? What is my research question? 12 Then further: Where and how can I answer my research question? Whom do I need to talk to or work with? 13

A great way to do all this is to go and find out, to leave the safe haven of the meeting room and get in touch with reality as quickly and as much as possible. To avoid a one-sided or biased approach, you use a mixture of different research methods; you might try the service yourself, 14 observe, 15 and do interviews 16 with customers, frontline staff, management – talk to as many stakeholders as possible. And don’t forget your basic desk research: 17 Have any of your questions been answered before? Is there any existing data you could use to inform your research? Who are the giants whose shoulders you can stand on?

Figure 9-1. PLANNING AND PREPARATION

Getting a project off the ground

These activities provide you with a wealth of material about the initial challenge and your initial research questions – a lot of real-world data 18 to challenge your assumptions. You might have gathered photo and video footage from interviews or observations, original quotes from users and staff about pain points with an existing situation, basic step-by-step documentation of their service experiences, deep knowledge about the context in which the user or customer is experiencing your service or product 19 (whether physical or digital), and so on.

However, this big pile of data and inspiration can be overwhelming. To make it accessible and manageable you need to break it down. One common way to do this is to create a research wall 20 and organize the data into mind maps (after you have identified useful categories 21, or to sort the material into models like current-state system maps 22 or journey maps. 23 Here, journey maps visualize the key experiences found during research, and help you to identify critical steps in each journey.

Figure 9-2. RESEARCH

Doing qualitative and quantitative research; synthesizing and analyzing raw data to identify patterns, opportunities, and key insights (e.g., using current-state customer journey mapping)

After you have had a hard look at all the data, you try to find patterns in your data: What are the actual needs, pain points, or wishes of the people involved? What are your key insights 24 about your users or customers that might help you to create a great service? What are the underlying (business) problems and opportunities? But also: what might be better questions?

You might have to collect some more data to fill in those gaps, refining your insights or creating even more. After a few research loops, the newest data does not bring additional insights to your research questions – and you move on.

You can now use this knowledge to reframe your initial challenge statement(s), thus making sure that you are solving the right problem and addressing the right opportunities.

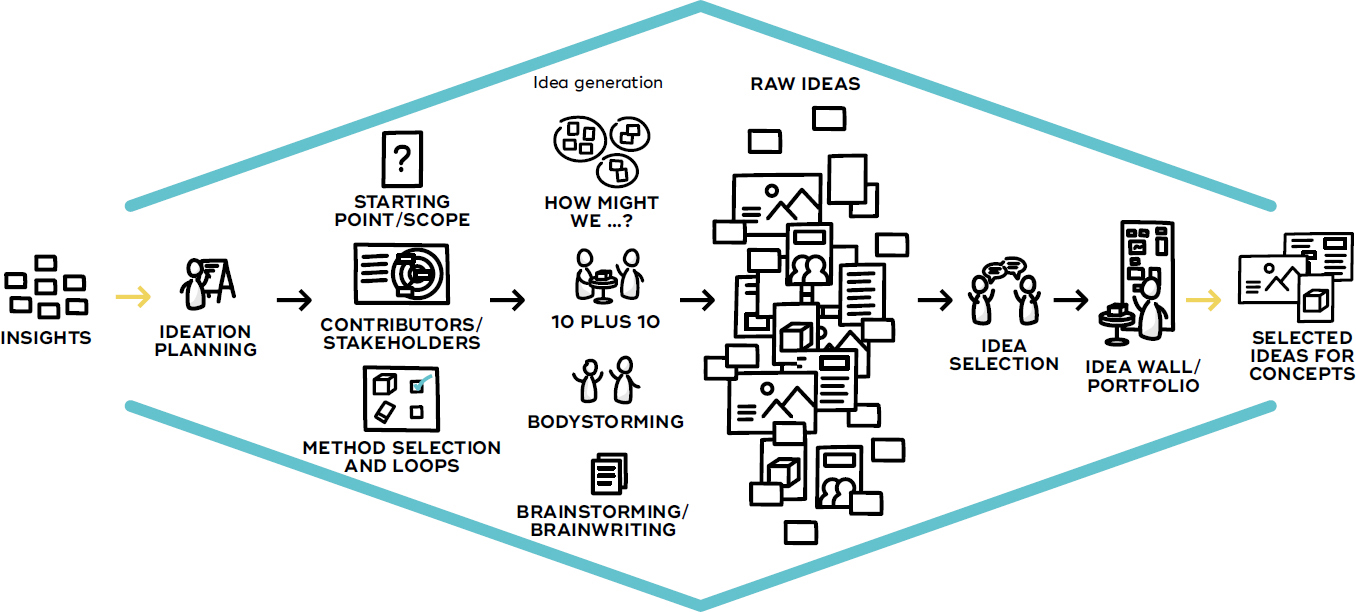

Figure 9-3. IDEATION

Using ideation methods to create as many raw ideas and concepts as possible based on research results and key insights; rating them in terms of feasibility and impact and selecting starting points for next steps

Ideation 25

During your research activities, you have consciously restricted yourself to exploring the problem space. Now that you have identified a real opportunity or challenge, you can move into solution space.

Your key question now is: how can I generate as many ideas as possible to maximize my chances of success? In order to achieve this, you look at the problem and assess who you need to invite 26 to contribute and co-create. And then you choose a matching mix of methods to leverage the participants’ knowledge and skills. For example, you break down your challenge into a set of trigger questions (“How might we …?”) 27 and use brainstorming or brainwriting, 28 10 plus 10 sketching, 29 and bodystorming 30 to generate many, many, many ideas. At this point, judgment (e.g., in terms of feasibility) is momentarily deferred to maximize your output during this stage.

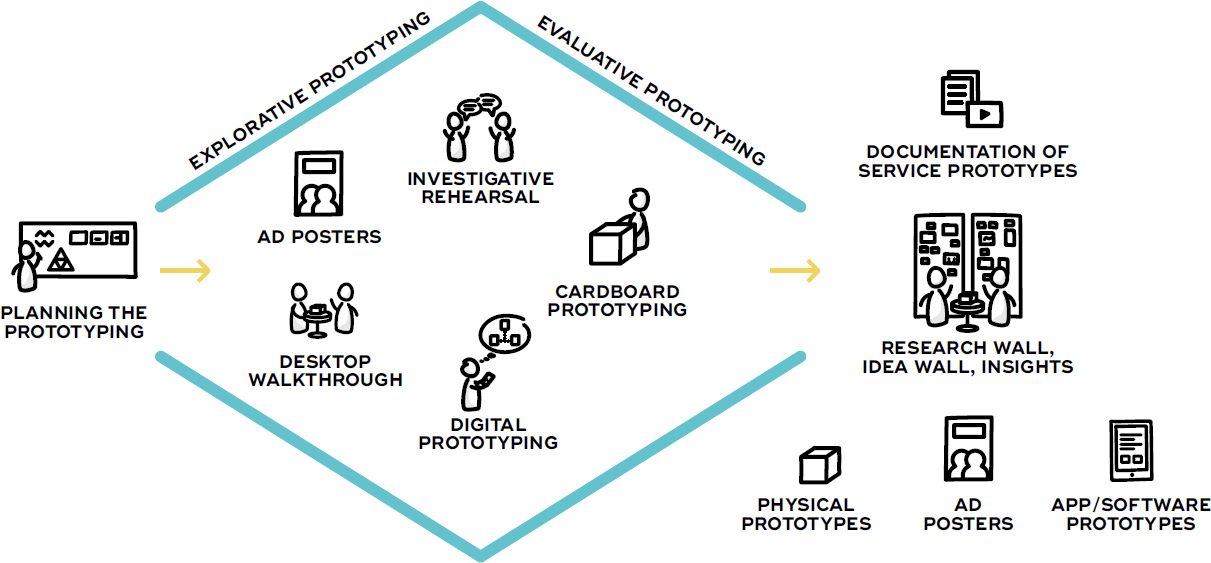

Figure 9-4. PROTOTYPING

Starting from your ideas, build prototypes – such as (service) walkthroughs, ad posters, digital prototypes, physical prototypes – and test them, break them, rebuild them, test them again, rebuild them again until you are ready to move on and commit to a certain direction

The next step is to work through all of those ideas and evaluate which ones should be developed further. One method that can help you to do this with a large number of concepts is the idea portfolio, 31 where all concepts are rated by two simple criteria 32 – often their impact on customer experience and their feasibility. The idea portfolio helps your team to focus their discussions and supports the decision-making 33 process. Which ones are the concepts you would like to take forward and explore more deeply?

Prototyping 34

You now have some promising ideas or concepts. That’s great, right? The problem is that up until now, all those ideas live in the Land of Ideas – where everything works.

The bad news is, we do not live in the Land of Ideas, and neither do our customers. We need to face (business) reality. Thus, you take your ideas and concepts into the real world by prototyping and testing assumptions with real users and other stakeholders before it gets too expensive. A design process aims to find out what works and what does not as early in the process as possible. This makes the design process not only faster, but also more cost effective.

You might start by creating explorative prototypes 35 to better understand the important aspects and implications of an idea. You might do some evaluative prototyping 36 (e.g., to validate your core value proposition). For both these approaches, you will employ tools like (service) walkthroughs, 37 service advertisements, 38 digital prototypes, 39 or cardboard prototypes. 40 You build, use, and learn from your prototypes, you break them, you rebuild them again. You open new doors and along the way create many valuable insights about your future service, but also you develop much better questions.

Expert Tip

Expert Tip

“Try prototyping multiple touchpoints together to show the value of designing across channels and, likely, silos.”

— Jamin Hegeman

Implementation 41

After some iterations, you have achieved a handful of working prototypes supported by working business cases and positive feedback from actual users. The activities during implementation now depend heavily on your project and what exactly you need to implement. Do you need to change internal or external operative processes, organizational structures, or procedures? 42 Do you need to develop and roll out software? 43 Do you have to develop and produce physical products 44 or change spaces and architecture? 45 Or do you need to implement a mix of all of those measures in parallel?

The answers to these questions will guide the methodologies you apply during your implementation activities. Implementation will often involve a lot more people starting to work on the project. And also, as every practical aspect of the service has to be created, tested, and implemented, there still is a lot of conceptual and design work left. This tends to take over the major share of a project. 46 In itself implementation also includes research, ideation, and prototyping. Often the only difference is which stakeholders are involved, as you start working with real employees on real stages with more depth and fidelity than before.

Planning for a Service Design Process

In this book, there is a conscious distinction between “planning of” and “planning for” a service design process or project. We usually talk about “planning for” because there are many details and activities in a service design project that you can prepare for, but cannot plan with precision beforehand. You will notice, however, that it is possible to set and keep milestones and – at the same time – keep an open mind to adapt the project as you go along. The planning of a service design project is actually the first iteration of your service design project.

Expert Tip

Expert Tip

“Exploring the brief together with the project sponsor is important, since you can get a good feeling of both expectations and possibilities. Sometimes this can lead to the rewriting and rescoping of a brief.”

— Simon Clatworthy

When planning for your service design process, your activities must fit within given business constraints, as you always have to consider how to best allocate time, money, and human resources within the project. 49 Specifically, planning for a service design process includes various activities which we will explore further in the following sections:

→ Clarifying the brief (including purpose, scope, and context)

→ Doing some preparatory research (to inform your planning process)

→ Making decisions about project team and stakeholders, project structure (i.e., planned iterations and activities), project phases and milestones, outputs and outcomes, multitracking, documentation, budgeting and mindsets, principles, and style

Expert Tip

Expert Tip

“Every project needs a scope. But the research and ideation should go beyond this scope, otherwise you may lose the most important parts.”

— Christof Zürn

Keep in mind that you might not need all of these, and you might not need them in this order. This is not a step-by-step manual but more a checklist to ask the right questions when planning for your process.

Brief: Purpose, scope, and context

The brief defines the actual starting point of your project and tries to capture the explicitly defined or implicitly assumed overall expectations about purpose, context, scope, and objectives. This also includes boundary conditions for the project in terms of budget, time, and other resources (and beyond). Often, however, you will not be approached with a perfect brief. Rather, people might have identified more of a rough starting point; an unmet need, a wish, a problem, or a seemingly brilliant idea like “We need to reduce the call volume in the call center by 10%,” “Develop that new service idea,” “We have this new technology, come up with something so we can sell it,” “Create new innovative business ideas,” “Fix the 20% drop in our NPS score,” “Improve the conversion rate of our online sales channel,” “Redesign the employee onboarding,” and so on. It usually is a good idea to clarify those together with the project sponsor and your team so everybody has a clear understanding:

→ Purpose: Why do we want to work on this challenge? Where does the challenge come from?

→ Scope/objectives: What do we want to achieve? What do we want to avoid?

→ Context: What is the context in which we want to achieve this? Where and when should the project happen?

→ Resources: What is the budget available? Who needs to be involved? Who will be able to contribute? What tools or materials are available?

→ Time: What are the expectations in terms of milestones and deadlines?

Preparatory research

Set up one brief iteration of preparatory research 53 to get a better feel for the size and complexity of the project, the ecosystem, 54 and potential research and development directions. This bit of research should deepen your insights about the content challenge as well as your understanding of the context, perceptions, and internal conflicts, or interplays that may emerge during the overall project.

Data collection for planning

Start with the inputs from the initial brief and do a quick brainstorm of potential research questions. It is not necessary to present them in a beautiful way, as they will only serve to support your planning session.

Select a couple of key questions and start your preparatory research sessions. It is important to remind yourself that this is not yet about doing the research and solving the challenge but planning your research and the rest of your service design process. You need to gather just enough data and insights to be able to set up a workable process structure.

If you have a bit more time for your planning, you can also add data from additional methods that deliver fast first results – for example, current-state stakeholder mapping, secondary research, autoethnography, online ethnography, or first (contextual) interviews. 55

Expert Tip

Expert Tip

“Consider visualizing your stakeholder map the same way you might create an ecosystem map. Show the relationship between stakeholders to understand whom to include during different parts of the process.”

— Jamin Hegeman

Assessment of potential development directions

Based on the data from your preparatory research, you should also create a first assessment of potential development directions. This can give you a sense of what you need to work on as likely outputs and outcomes, as well as whom you might need to involve during ideation, prototyping, and implementation. Of course, this can and will change as you go through your project, but it is important to have this first idea to discuss and allocate reasonable budgets, time, and resources. Hence, no matter what you find (or don’t find, for that matter), it is key to truthfully acknowledge the level of uncertainty with respect to potential types of solutions. For example, if you know your project scope involves updating an existing app, you can plan and budget in the appropriate resources from your UX and development teams. But if you cannot yet tell what type of solution you will be implementing, it might be helpful to plan and budget for a pilot project, giving you the time and resources to clarify more concrete development directions first.

Project team and stakeholders

Assess who might be affected by your project and whom you need to include in which activity. This should be based on the insights from your brief as well as on your preparatory research and any initial planning efforts. “Where does the project brief come from?” and “Who needs to implement this?” are just two important questions you should always ask yourself when you start a project in an organization. You might, for example, learn about similar projects and identify people who were previously involved. They might be able to assist you in selecting your project team and managing important stakeholders.

In many ways, all the people on your project are the customers of your service design process. Reflect on their skills, needs, and pain points and design the process for them. Your design process should be there to support them and to leverage their knowledge, skills, and talents.

Core project team

The role of the core project team is to manage and support a project and to facilitate the design process through appropriate workshops and activities. You are aiming for a good mix of service design skills and subject matter expertise. However, not everybody on the core project team needs to be an expert in service design. Similarly, not everybody needs to be an expert in your industry or to have a deep knowledge of your organization. 60 For a single service design project, the core project team usually consists of a handful of people, but it can be as small as a team of one (e.g., working as a coach within an existing project structure) or as big as a football squad (e.g., running and implementing a project for an internal or external client).

Expert Tip

Expert Tip

“It is always worth spending five minutes thinking about your role, as a designer, in relation to each of the stakeholders.”

— Simon Clatworthy

Decide which of the following roles are relevant to your project and organization, or if you need to create new ones (note that each member of the core team might take over multiple roles):

→ Service Design Management Lead: Plans and manages the overall service design process and manages the project team

→ Facilitation Lead: Ensures continuous feedback and learning, facilitates team collaboration, and provides design support or facilitation of co-creation workshops

→ (Service) Design Lead: Focuses on content and quality of service design outputs and deliverables; shapes and delivers design concepts

→ Business Lead: Ensures business viability of developed concepts; deals with business models, KPIs, benchmarks, business strategy, competitor analysis, etc.

→ Technology Lead: Analyzes technology requirements, ensures feasibility of new concepts, and manages and supports prototyping efforts

→ Change Lead: Focuses on the human perspective; assesses the impact on staff and customers from an individual and organizational change management perspective, and develops fitting change solutions

→ Project Manager: Keeps the team on track; manages the service design process in terms of budget, deadlines, and reporting; administratively backs up the project team

→ Project Owner/Sponsor: Takes responsibility for strategic direction and budget – the person who assumes this role is often a key decision maker

Extended project team

Most projects are also supported by an extended project team: a larger group of people with specific competencies that can be involved in specific sections or activities within the project. 61 Hence, the team size of an extended project team can vary over time and even change from workshop to workshop. Consider including: 62

Comment

Comment

“The advantages of bringing everybody to the same table [are] enormous. Using the various team members to co-create on tasks, roles, and structure can be a powerful instrument to create ownership.”

— Francesca Terzi

→ An internal selection of cross-functional members to ensure a holistic perspective.

→ External method or subject matter experts to manage the competencies that your organization does not have (e.g., ethnography, UX, change management, architecture, etc.).

→ Departments and/or external stakeholders that are responsible for earlier or later parts of your project, but also involved in daily operations.

→ Key decision makers from your organization. The success of your project might not just depend on the quality of your output but also on the hierarchical position of the decision makers who support it. Put careful thought into how to integrate them closely into your project team from the beginning. 63

→ Users or customers, as ambassadors of their stakeholder group. This allows quick research and prototyping without a lot of planning.

→ Generally, any people who are directly affected by the project, or who have the power to stop it.

It is crucial that you involve affected staff as early as possible in the design process of their future daily work routines. This makes them co-owners of the new solution, a status which will help implementation and acceptance.

Structure: Project, iterations, and activities

Your project structure lays out how you want to create and advance the expected outputs and outcomes as defined in your brief.

Each higher-level iteration involves at least some activities of research, ideation, and prototyping. Just like in build-measure-learn cycles, 64 you create potential solutions in the shape of prototypes or implemented services, use them, and systematically learn from them. This implies that you most likely need to adapt your original planning or even change as you go along.

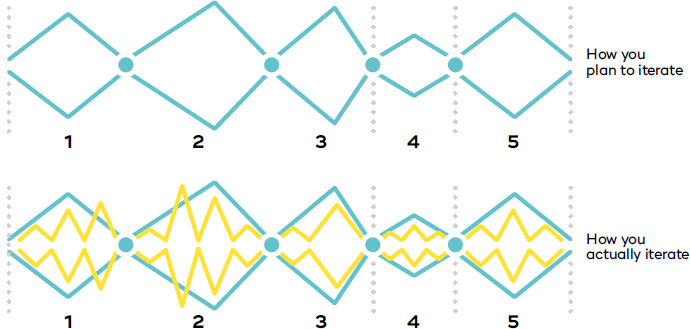

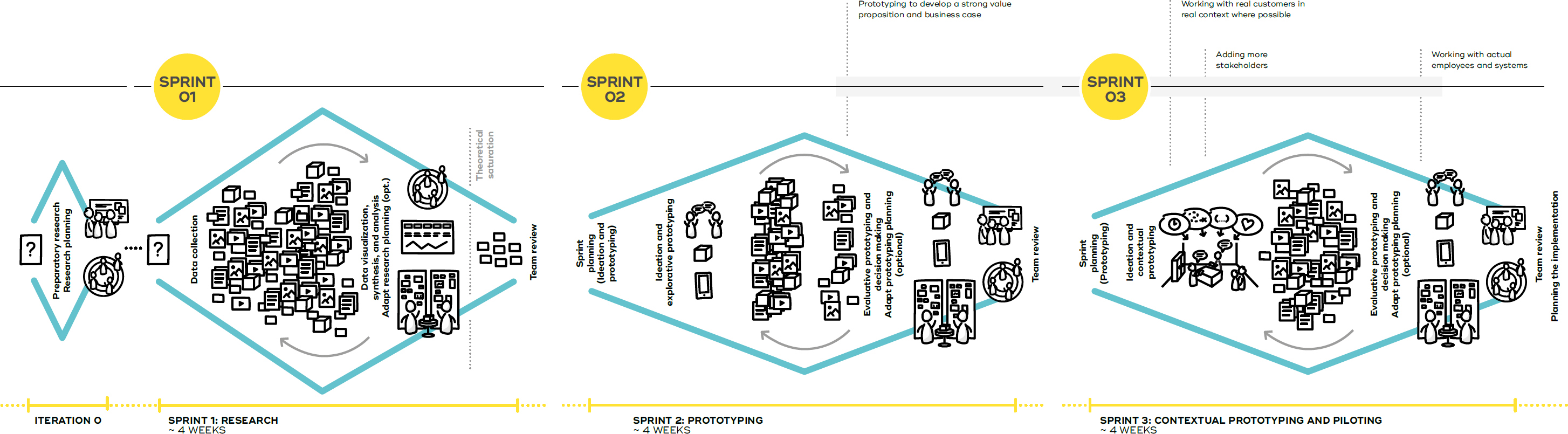

Figure 9-6. PLANNED ITERATIONS

Consider breaking up your project into a planned sequence of smaller projects to deal with uncertainty and reduce the risk involved.

Breaking up your project

It can be helpful to break up your project into a planned sequence of smaller projects to deal with uncertainty and reduce the risk involved. Sometimes a short but well- prepared iteration like a five-day service design sprint can be enough to have a great impact on your results. 73 This structure introduces clear points for reflection and decision in between projects that allow you to stop a certain development direction early if necessary. 74

Comment

Comment

“Experiments and pilot projects truly matter: they can be a starting point for larger innovation initiatives [and] provide a fruitful context for testing tools, exploring processes, or experiencing new models of value creation. Learning from piloting can be a powerful driver for change in organizations and markets!”

— Kathrin Möslein

The different projects can also put a different emphasis on certain service design activities compared to others. The following options are certainly not a complete list, but might help to give you some basic orientation:

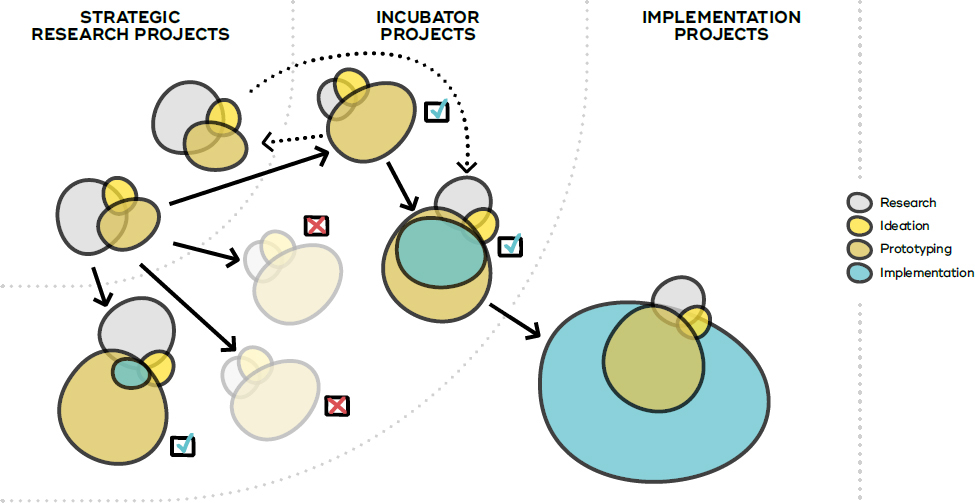

→ Strategic research and innovation projects

If you are quite far forward in your innovation funnel, you might want to set up a strategic research project. Strategic research and innovation projects are usually not intended for implementation, but instead help to create meaningful starting points for more incubation, or implementation-oriented service design projects. Their main focus is clearly on research even though they end with a first couple of steps into solution space – for example, creating validated opportunity areas, lighthouse concepts on a prioritized idea portfolio, and first early communication prototypes to make those concepts more tangible.

→ Incubation projects

If you are trying to explore and validate the market potential of one or more concepts, it makes sense to split your project into a sequence of incubation projects with growing budgets and resources. Incubation projects have a strong focus on experience prototyping, which delivers real data about the risks and market potential of each string of concepts.

→ Implementation projects

If the solution space is sufficiently defined, you can plan straight for prototyping and implementation in a series of iterations within one project. Even though there still needs to be a strong emphasis on research and prototyping at the beginning, over the whole of the project most of the time and resources will go into implementation activities.

Figure 9-7. PROJECT PORTFOLIO

The mix of service design activities in your project portfolio changes as you move from early stages of strategic research toward implementation.

If you cannot yet see the shape of a potential solution, 75 there is no way you can safely create a sound implementation plan or project. This would depend too much on the intermediate results of your research and prototyping activities. Start with a strategic research/innovation project or incubation project first.

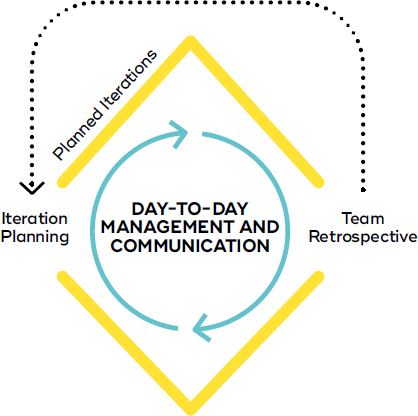

Planned iterations

Within your project, planned iterations are iterations you promise to do and deliver on time and within budget/resources. 76 Each planned iteration consists of three parts:

Iteration planning

Service design activities

Reflection on content and process

Planned iterations are the predictable timeboxes you set up for your design activities – a safe space to do, learn, and adapt. They are the primary iterations you need to focus on during your planning activities as they also define ahead of time when you will invite stakeholders from outside the project team for co-creation and decision making. A prominent example of planned iterations is the sprint structure you find in agile software development methodologies like Scrum. 77

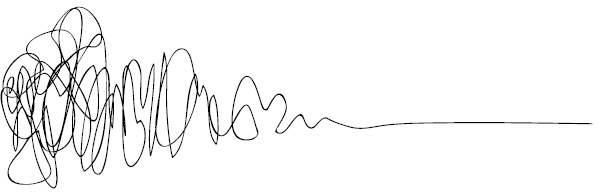

Figure 9-8. The Squiggle: 78 This famous illustration shows how people can experience the design process as strange, almost chaotic. Using planned iterations helps to bring a solid structure but at the same time leaves enough space for exploration.

Figure 9-9. Planned versus actual iterations: Planned iterations create a formalized uber-structure for planning, service design activities, and reflection to stay iterative and adaptive at all stages of your service design process.

With planned iterations, you create a formalized uber-structure which establishes a set rhythm of planning, service design activities, and reflection to stay iterative and adaptive within your service design process. This keeps your team on track, and especially helps stakeholders who are not accustomed to this way of working.

Still, people who are experiencing service design for the first time (or looking in from the outside) can perceive it as arbitrary and almost chaotic. “Explorative and iterative work” is often misunderstood as “playing around and doing what you want.” Planned iterations help you to actively address and manage this perception.

The amount of freedom – or “wiggle room” – within your planned iterations depends on the experience of your design team. If you are working with inexperienced designers or an interdisciplinary team not accustomed to this way of working, keep the planned iterations tight and closely coach them through them until they pick it up. 79

If you are working with experienced designers, you can trust them to iterate within the given boundaries as necessary. The typical length of planned iterations often ranges between two to four weeks.

It is important to make space regularly for reflection sessions focused on your process and future iteration planning, taking time to adapt to what you have learned so far. Usually, reflection sessions are put at the end of a planned iteration. With shorter iterations they can be quite informal, but make sure you always also conduct formal review and planning sessions at least at the end of higher-level iterations.

Expert Tip

Expert Tip

“It’s not just difficult to visualize, it’s sometimes difficult to follow, unless you are used to it. Designers jump forward and backwards, zoom in and out, always on the hunt for something new, something that can inspire an innovation. If you are used to structure in everything, this may be challenging and difficult to follow. But ... there is method in the madness – give it time.”

— Simon Clatworthy

In your reflection and iteration planning, you need to consider the content, tools, and methods as well as the way you collaborate within your team: What did you learn in terms of your project content, and what needs to happen in the next iteration in terms of tools and methods? How was the collaboration in the team and what can you do to become more effective as a team? 80

The key driver for cyclical and iterative methodologies like the service design process is the desire to reduce the risk at each single step while at the same time maximizing learning to make subsequent steps more efficient.

Planning core activities

The most important aspect of this part of the planning process is to create a preliminary plan which accounts for continuous iteration planning and content/process reviews along the way. These activities will become the cornerstones of your adaptive and iterative process. In the following pages, we sketch out how to create a more detailed picture of your research, ideation, prototyping, and implementation activities. Initially this will help you to put together a proposal, including a roadmap, a list of resources you need, and a budget. Later on, this becomes a living document as you adapt and improve.

The planning of your service design activities is also iterative in itself. So, plan your first iterations quickly, then come back and adapt and improve. Chapter 5–Chapter 8 81 give you in-depth descriptions on how to plan your research, ideation, prototyping, and implementation activities when you are about to do them. During the process of planning, however, you need to balance the uncertainty at the time of planning (pre-project) with the need for just enough detail to at least be able to create a budget and key milestones. For each iteration, it is helpful to be able to communicate a clear picture of how you want to work, creating trust in your process and your project team.

Be aware that at some stage it might become pointless to plan for an iteration which is too far into the future – even if your client is pressing for it. In those cases, it might be helpful to sketch out an exemplary project framework based on a typical service design process, knowing that you only will be able to properly plan it when you get there.

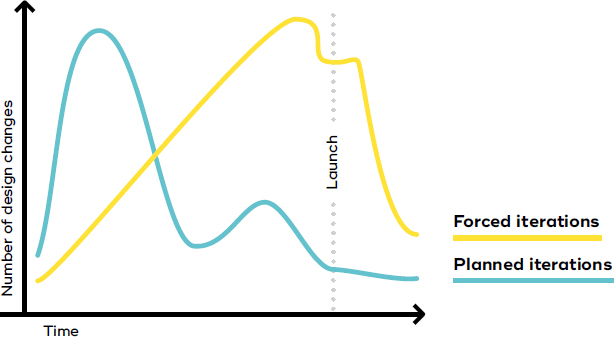

Figure 9-10. PLANNED ITERATIONS VS. FORCED ITERATIONS

In the forced iteration model, necessary changes are only forced onto the team by imminent implementation deadlines. The team is mostly reactive; changes are expensive.

Using systematic research, ideation, and prototyping loops, the planned iteration model pushes design changes toward the beginning of the project. The team operates proactively; the cost of changes is low. 82

Plan for research

→ Review your initial research question(s), preparatory research, and high-level iteration structure.

→ Select research methods: Line up a sequence of research methods and decide how to analyze and visualize them. Roughly guesstimate typical setups in terms of sample selection, sample size, researcher team, data types, and triangulation strategy.

→ Consider potential researchers: Briefly refer back to your stakeholder map or do a quick informal brainstorming on potential stakeholders. How much of the research can be done by the project team? Where do you need external help?

→ Split activities into planned research loops: Sketch out how you want to arrange the selected methods into different research and analysis/visualization sessions and how they feed into each other. Add adaptive iteration planning and review sessions.

Plan for ideation

→ Review your initial assessment of potential development directions.

→ Consider potential participants: Very briefly (as this will certainly change after your research activities) refer back to your project stakeholder map or do a quick informal brainstorming on potential experts or stakeholders for key opportunity areas.

→ Select methods: Line up a sequence of ideation and decision-making methods to fill your idea portfolio and select them. Guesstimate how many ideas you might want to take forward into prototyping.

→ Split activities into planned ideation loops: Sketch out how you want to line up the selected methods into different ideation and decision-making sessions and how they feed into each other. Add adaptive iteration planning and review sessions.

Plan for prototyping

Expert Tip

Expert Tip

“During planning, keep in mind that the project members and co-creators are embedded in organizational structures: your activities may have unforeseen effects going beyond your project environment. To avoid friction, carefully consider how these individuals perceive your service design activities and what effects their experiences may have.”

— Julia Jonas

→ Review your initial assessment of potential development directions. 83

→ Assess what you might have to make: Remember that at this point you might only be able to plan for approximate types of prototypes (e.g., if you already know you are going to work on an app, a consulting session, a physical product, etc.). It might also be impossible to say what needs to be prototyped just yet. However, in many projects the expected outputs are quite well defined and can guide your planning. It might be important to assess the uncertainty of your planning so you can adjust as you move forward.

→ Select explorative and evaluative prototyping methods and plan supporting research: Line up a sequence of explorative and evaluative prototyping methods. Roughly guesstimate the typical fidelity, multitracking, context, audience, and audience size for each of those methods. Remember to select supporting research methods to learn from for each of your prototyping activities.

→ Consider potential prototyping skills and team(s): Do a quick informal brainstorming on potential skills you need and experts or stakeholders who have those skills to create the prototypes you need. Plan for interdisciplinary prototyping teams – who can make almost anything – at early iterations and include specialized skills later on.

→ Split activities into planned prototyping loops: Sketch out how you want to line up the selected methods into different explorative and evaluative prototyping sessions and how they feed into each other. Add adaptive iteration planning and review sessions.

Plan for implementation

→ Assess what you might have to make: Planning implementation means planning based on assumptions of what you might have to make. This will be based on your guesstimations of the prototyping activities and will share a similar uncertainty.

→ Consider potential implementation skills and team(s): Break down the implementation task into the involved disciplines. Do a quick informal brainstorming on potential skills you need and experts or stakeholders who have those skills to implement the project as it is planned today. Just like when you are planning for prototyping, it is often useful to plan for a core interdisciplinary implementation team – who can plan and manage almost anything – at early implementation iterations and move toward more specialized setups later on. Those might change, but having the interdisciplinary team at the beginning buys you the necessary time to adapt and communicate any changes as early as possible.

→ Involve specialists to do implementation planning: Line up seasoned project managers to give feedback on planning the implementation part(s). Co-create individual implementation plans together with the specialists.

→ Split activities into planned iteration loops: Sketch out how you want to line up the selected methods into different implementation loops and how they feed into each other. Add adaptive iteration planning and review sessions. As implementation activities are often done in parallel, make sure you sync those activities and continuously check the progress of single work packages against the holistic customer experience.

At any given stage, the higher the uncertainty in the outputs of your design process, the more parallel concepts or prototypes you should keep in the game.

Multitracking

Decide how many insights, ideas, prototypes, or services you want to work on. In bigger projects, it often makes sense to multitrack your iterations – for example, split the team and work in parallel.

Multitracking can be used to reduce risk by exploring a certain number of concepts or prototypes instead of just one. Not putting all your eggs into one basket allows you to strategically deal with uncertainty in your concept portfolio and manage the expectations of stakeholders.

Essentially, by working in this way you replace the old model of making one big bet on one concept with a series of smaller bets on a handful of promising prototypes. This reduces the risk associated with each individual decision and substantially reduces the risk associated with your overall innovation and design project.

Later, when you are closer to implementation, you can use multitracking to divide the work on different elements that need to be implemented into parallel work streams to speed up the time to delivery. For example, creating the interior design for a shop environment, creating training sessions for the staff, and implementing a support app can certainly run in parallel. Depending on the complexity of the development tasks, each work stream can also run at a different iteration speed. To keep the different work streams on track, regularly align the progress and make sure the output fits together. 84

Project phases and milestones

Gantt charts, project phases, and milestones are the currency of traditional project management. They have their roots in the world of more or less deterministic projects that could be planned and executed using basic work-breakdown structures, analyzing work package dependencies. While we strongly suggest you avoid using Gantt charts to plan and manage your project, you might still have to deliver milestones and a roadmap to comply with internal requirements. 85

Comment

Comment

“While it’s tempting to want to check off the box and move on, designing a service is never done. It’s only over when you go out of business.”

— Jamin Hegeman

One way to deal with this situation is to use a black-boxing approach. You try to encapsulate the activities of your service design process in such a way that – from the outside – it almost looks like any other project. Ask yourself: how might we adapt our service design process to fulfill the (reporting/planning) requirements for projects within our organization, without giving up the iterative and adaptive nature of the service design process? Be careful with black-boxing service design projects, though, as it is just a workaround. It might be a starting point for service design within an organization, but it should not be the default.

The approach you choose will depend on your own experience and the previous experience of stakeholders with iterative and adaptive development approaches. Here are a few starting points.

Identify and map project phases

Have a look at periods of iterations within your design process where you can identify a dominant activity or scope. Mark them as overarching project phases for your project. Often they combine a distinct mix of activities, methods, and deliverables. Map them to align with existing iterations. Sometimes it is useful to play with the naming of your project phases to match with existing terminology. For larger service design projects, mapping project phases onto your service design process can also be used to give a sense of orientation and progress. Here are some examples of project phases:

→ Preparation phases, setup phases, scoping phases, or initial iterations often include project planning and prep research, but sometimes also some first research, ideation, and even prototyping activities. You might even do a very quick first iteration including all these activities to better plan the entire project.

→ Discover phases, insight phases, pre-project phases, or research phases might package early, research-heavy high-level iterations, but will usually also contain some ideation and lightweight prototyping.

→ Concept (development) phases, design phases, or ideation phases might package ideation-focused high-level iterations but will also contain research and at least some lightweight prototyping.

→ Prototyping phases, build phases, or incubation phases allow you to package prototyping-focused high-level iterations, but might also include some research and ideation activities.

→ Internal alpha, local beta, beta, or rollout phases allow you to plan phases around user engagement or the user learning curve.

→ Delivery phases, implementation phases, pilot phases, or rollout phases allow you to package different implementation-focused high-level iterations.

→ Operation phases or in-production phases allow you to package the continuous improvement iterations of the standard daily operations after your go-live. Service design is then set up as an ongoing activity in an organization and brings holistic cycles of research, ideation, prototyping, and implementation activities to the daily operations of your service.

Set outputs and milestones

Milestones mark specific points on your project timeline at which you reach an agreed status. They often are also the points in a project where you present to or involve a wider audience and communicate the progress and status of your project.

Set up your milestones to match your planned iterations – and carefully manage the expectations of what you can or cannot deliver at those points. The outputs you promise should be specific, measurable, and realistic and will often be called deliverables here. 86 Typical milestones include:

→ Intermediate research report done

→ Key insights identified and prioritized

→ Opportunity areas identified and prioritized

→ Ideation sessions done with key stakeholder groups

→ A defined number of ideas generated

→ A defined number of detailed concepts developed

→ A certain number of low-, mid-, or high-fidelity value/look-and-feel/feasibility/integration prototypes tested and feedback analyzed

→ A certain number of prototypes tested with real customers and feedback analyzed

→ Business cases for a defined number of prototypes validated

→ Pilot with frontline staff done and analyzed

In contrast to traditional projects, your deliverables stay living outputs. They will grow further and change as you go forward.

In some organizations these milestones might be squeezed into an existing stage-gate process, often consisting of phases like discover, scope, plan, develop, test, launch, and review. Even if this is not ideal, it unfortunately often reflects business reality. Between these stages, there are gates – decisions on whether a project will get a (conditional) go, be put on hold, be recycled, or be killed. Be aware that if you “black-box” an iterative structure with labels like these, you’ll still need to meet existing hard criteria at each gate to get a go for the next stage. Often, you can define “must-have” and “nice-to-have” criteria for each project stage. Try to define the criteria mentioned in this chapter as “must-haves,” since you can be certain you will meet them if you follow the process.

Outputs and outcomes

Going beyond the tangible

Many service design activities will have tangible outputs (e.g., research data, documented insights, idea sketches, prototypes, research and project reports, etc.). However, as we have seen throughout the previous chapters, sometimes the more intangible or implicit outcomes of your design activities will be more important for you. For example, early prototyping activities might primarily be used to create a shared understanding and alignment amongst the interdisciplinary project team – and are not just done for the ideas. 87 Or take qualitative research: while you collect a lot of concrete data on your research wall, one of the key goals might be to create empathy with your stakeholders within the design and management team. That’s not something you can put into a report.

Expert Tip

Expert Tip

“Carefully manage expectations throughout the innovation process. Otherwise, especially after intensive innovation workshops, clients will demand that the specific individual solution they developed be delivered [too] soon afterwards.”

— Julia Jonas

Even though the rest of your organization will usually be looking at the tangible outputs, it is equally important to carefully assess and plan your intangible outcomes. They often turn out to be the driving factors for successful co-creation, reducing resistance within the organization and increasing your chances to implement in the long run.

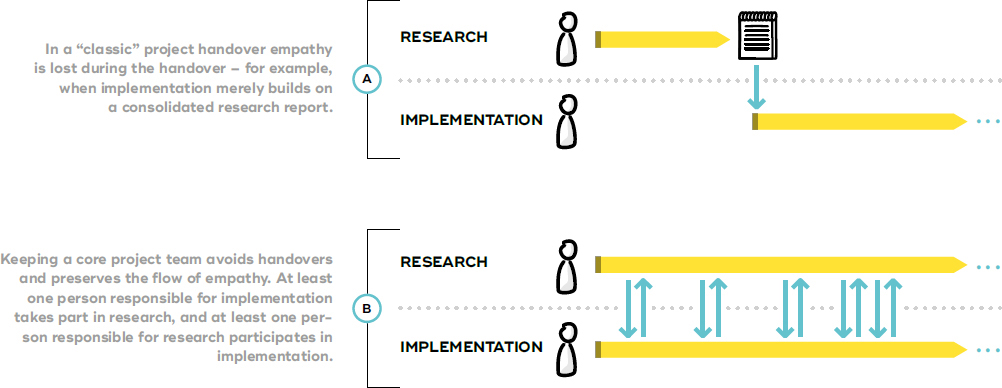

Flow of project knowledge, ideas, and insights

Key intangible outcomes (like empathy and deeper contextual knowledge and understanding of the stakeholders, the problem, and potential solutions) are almost inseparable from the people who developed these in your team. While some stakeholders are part of the project from beginning to end, many more will only join for some parts of the journey. This offers an opportunity for new ideas and perspectives and raises the challenge of passing on the important knowledge so they can meaningfully contribute. When people leave the project there is also a danger of losing essential parts of that hard-earned empathy, deep knowledge, and understanding. Plan to keep the flow of knowledge and empathy intact by building an unbroken chain of people across the project,supported by tangible documentation.

It can be helpful to map out the flow of people, key outputs, and outcomes across your design process to better understand where empathy, deep knowledge, and understanding are generated and how they are passed on to upcoming steps – through people or through tangible outputs like documentation or prototypes.

Figure 9-11. FLOW OF EMPATHY

Handover through documents will not carry over empathy. Keep up the flow of empathy by keeping key people in the project from beginning to end.

Documentation

Decide early how you are going to organize and create your written 88 project documentation. Check (e.g., with your project sponsor) whether or not there are any requirements on form and content. Depending on the industry you work in, there might be strict rules and obligations. Documentation can be tedious and hard work, especially if it is done in retrospect, so plan this well ahead of time. Build it into the activities themselves as much as possible, or at least do it while your memory is still fresh.

Document your process and decisions

The service design process is adaptive and iterative. As you are constantly reviewing your progress and making changes, the real process will deviate from your original plan. As you go along, create concise documentation of the changes you made and the underlying reasons. This can be as simple as filing handwritten meeting minutes, or just taking photos of flipcharts or sticky notes that contain those details. However, it might also be necessary to prepare a glossy slide deck to run a decision past the board or to follow an official template for change requests.

Important decisions that are undocumented might be challenged, creating unnecessary discussions or, in the worst case, forcing you to do over.

Document your tangible outputs

Most activities in the service design process have tangible outputs which in turn act as the inputs for the next set of activities. These outputs are important for your documentation as they allow you to trace back outputs like prototypes to the underlying insights from research or even back to the original quotes from your research data. 89 A simple indexing system can help to connect the original data from your research to your prototypes or implemented solutions.

Expert Tip

Expert Tip

“It takes the whole organization to create and deliver services to market. The intangible benefits are equal to, if not more important than, the tangible outcomes, as without understanding and alignment, your team may contribute to creative pollution that never gets implemented.”

— Jamin Hegeman

If a piece in the chain is challenged, you can retrace some steps and re-examine the underlying assumptions or conclusions, or explain where it came from and who contributed. 90

Keep the documentation accessible

You should decide up front how and where to store your tangible outputs so you can make them accessible quickly at any stage later in the project. In smaller projects, a big project room with plenty of wall space might be enough. There, you can sort all the assets onto your research wall and idea/concept wall and exhibit your prototypes on tables or in a distinct area. In more complex projects, you should still keep a physical project space for key assets, but also plan for a structured virtual space where you keep the complete dataset. 91

Expert Tip

Expert Tip

“Project rooms and project walls within a client building are important ways [of] engaging passers by and spreading interest.”

— Simon Clatworthy

Figure 9-12. A BREADCRUMB CHAIN OF EVIDENCE

As tangible outputs are the physical evidences of your service design process, your documentation trail becomes your chain of (physical) evidence, complementing your chain of empathy. Such a chain helps to find raw data revealing the problem your developed prototype strives to solve. Indexing helps to keep track. 92

Documenting the intangible outcomes

Decide which of your intangible outcomes you want to add into the official documentation, and how. Many organizations have a bias toward the tangible outputs, and making sure you document the intangible outcomes can help you shift that focus toward a more balanced view. For example, you might include photos and use storytelling from a high-energy prototyping jam to underline the effects on interdisciplinary collaboration and alignment on shared goals (“We have never seen them work together before!”).

Expert Tip

Expert Tip

“A dedicated project room is key for service design work. It allows teams to keep insights, maps, ideas, and tangible artifacts visible; connect dots; and navigate problem framing, scope definition, and the nonlinear nature of the process.”

— Jamin Hegeman

Be careful though, since this is not always easy to do. Some of the effects can be quite subtle or hard to show. Reflect on this within your core project team and strategically include the parts you feel comfortable with.

Budgeting

After completing the first planning cycle, you should have a good first idea of your core project and planned iteration structure, an initial baseline of core activities, and a sense of the size of your core and extended project team.

Also, you can guesstimate the amount of travel, materials, and external services that are required. This gives you plenty of input for an initial draft of your budget. In that sense, budgeting for a service design project can be really easy, or it can be as hard as in any other project. Here are a few tips:

→ Always start with a ballpark figure. If you have a target range, you can make sure you are not over or under planning. Then get more detailed. Iterate.

→ Break up big budgets to reduce risk. If you aimed too high, consider breaking up the project into a sequence of smaller projects with increasing risk and budget. If you are too low, add depth or more iterations.

→ Consider budget thresholds. Make sure to check the budget thresholds of the organization you are working in/with. What is the maximum budget your project sponsor is allowed to sign off? If you have to aim higher, who else will have to be involved (and convinced) to sign off that budget?

→ Plan with typical content. As you cannot plan later iterations in detail, budget for typical work packages instead which are – from your experience – within the parameters of your project brief and the expected output and outcome.

→ Use group estimates. Seek out experts and experienced project managers to help estimate efforts and resources for each of your planned iterations. Use lightweight methods like planning poker 93 to create meaningful discussions and arrive at realistic group estimates to remove individual bias.

→ Plan with an appropriate buffer. Often people try to build in a buffer across the board to cater for unforeseeable challenges. While you can take the deviations from your mean estimates as an indication, 20% seems to be a frequently used value – but your mileage might vary. If your project budget is estimated by multiple people (e.g., subproject leads) make sure you are not adding buffers onto buffers.

→ Manage expectations. Make sure people understand that the content within your iterations needs to be flexible. Your budget accounts for overall time and resources, but you must to have a certain flexibility in how you actually spend your budget and allocate your people within the process. Clarify how to handle those changes.

→ Understand calls for tender. For big projects, make sure you have a clear understanding of the sourcing procedure/tender process of your client organization. Purchasing departments will try to haggle and bring the price down. Decide whether or not you want to play their game and set your prices accordingly.

Mindsets, principles, and style

Think about the “soft” side of how you do things. On paper and even in terms of the method mix, many design processes look the same. But people are different, including the people working on your service design project. You will find a broad variety of mindsets, principles, and styles. While most practitioners with experience in service design share a common mindset and set of core principles, there will still be small but important differences. What is the vibe of the facilitation? Are you all speaking the same language? How do you interpret your role as a service designer?

Depending on the ecosystem you are working in and your role, there is broad range of styles that you can bring to the table. Are you the engaging ones in suits or the thoughtful ones in turtlenecks? Is your background in design or do you come from the technology or business side of service design? Are you an external agency that offers to create and implement breakthrough projects with a team of experts? Or are you a service design coach who enables people inside the client organization to do service design on their own? Or a project owner inside an organization who needs to figure out how to work with colleagues?

If you are shopping for an agency or consultant, this might be one of the key points for consideration: Is there a cultural fit between my organization and the agency? Or, if you are implementing a service design project within your own organization, what will be your way? 95

Managing The Service Design Process

Iteration planning

Iteration planning regularly adapts your planned iterations and roadmap to the learnings of any previous activities. After completing a planned iteration, use a sped-up version of the planning process described in the previous section as a base to update your planning. Where necessary, use the planning sections in Chapter 5 through Chapter 8 to do detailed planning of core activities for in-depth research, ideation, prototyping, and implementation iterations. Typically, for most iterations of your project the iteration planning session of the next iteration will be combined with the iteration review of the previous one.

A planned iteration structure with fixed dates for iteration planning and review also helps to manage the ideas and change requests you will receive from project sponsors and stakeholders – often on a daily basis. Those requests can wreak havoc on your project if not managed carefully. Communicating a clear structure of review and planning sessions can help to channel most of those requests. If the next session is not too far off, people are often happy if their new ideas and change requests are officially documented, assessed, and prioritized during the next planning session.

Discuss change requests or process feedback in your iteration review session. Put new questions, ideas, or changes onto your research wall or idea portfolio to be prioritized and added to your overall project funnel.

Figure 9-13. Overview of service design management activities: iteration planning, content reviews, team retrospectives, and day-to-day management and communication.

Iteration management

Manage focus between big picture and details

One of the key elements of service design is the constant switching between different aspects of the service – from the big picture to the details. Practically this means, for example, going back and forth between a focus on details (like single steps of the customer journey or even specific user stories or jobs to be done) and the orchestration of the end-to-end customer journey across all those steps. Make sure to balance your attention between working on single touchpoints versus consistent and iterative development of holistic service experiences.

When you are managing a service design process, it is important to do this systematically. Decide which perspective might be most valuable as a next organic step in your process (e.g., customer experience, stakeholder network, business model, organizational feasibility, or technological feasibility). But then also check the effects of the changes you’ve made on the service as a whole. This is especially important when you have split up the project team and started to work in parallel. Build those checks into your regular project structure – for example, by attaching them to specific milestones in the process.

Manage problem and solution

The same back-and-forth applies to the interdependence of problem and solution. When navigating through your iterations, make sure to keep a constant eye on both your potential solutions and whether they trigger new problems which might lead to new, better solutions. These kinds of iterations can be observed in the design behavior of experienced designers and often happen organically. If you and your team are new to this, you might have to explicitly step back and reflect on where you stand in this problem-and-solution space: “Proposed solutions often directly remind designers of issues to consider. The problem and solution co-evolve.” 100

Day-to-day project management

In terms of the daily tasks of project management, service design projects are not much different than other projects. Here are a few tips to help you stay sane:

Expert Tip

Expert Tip

“Over time, not only the scope of the project but also the environment around it may change, for example through new employees or the launch of new projects. It is therefore advised to periodically update tools like your project stakeholder map to review the overall situation and reflect on such changes.”

— Julia Jonas

→ Do. Now.

Service design is about doing. Refer to Chapter 5, Chapter 6, Chapter 7, and Chapter 8 for tips on how to do and manage specific activities.

→ Talk briefly. But talk often.

If you do not align with your fellow project team members, things can quickly go astray. But outside your core service design activities, try to keep coordination efforts lean and efficient. Consider introducing a daily stand-up meeting (see textbox) to align the team on a day-to-day basis and make sure problems get identified and solved quickly.

→ Make process and progress visible – preferably physically.

One of the biggest problems in projects arises when activities are stuck and no one notices. Create visual process and progress boards and put them up in your workspace so everybody can see them and trigger action if necessary. Of course, if you are working with a distributed team you might have to switch to a virtual solution. But the rule stays: make sure it does not get buried in a file folder far, far away, but becomes visible in a popular virtual space (e.g., the start page of your internal social network).

→ Keep your rhythm.

When a project hits a tricky problem, it can be tempting even for experienced designers to lengthen the current iteration until team members feel they have the perfect solution. Resist this temptation! Timeboxed iterations with regular reviews 101 are even more valuable at times like this.

→ Orchestrate quiet times and times of intense collaboration/exchange.

Service design can be used to seek solutions for wicked problems. This can be hard and requires a deep understanding of the matter. Try to create safe spaces of uninterrupted work time for people to dig into those challenges. During those periods, prefer asynchronous communication like email over instant or face-to-face communication. At the same time, make sure there are enough opportunities for formal exchange (i.e., workshops) as well as plenty of informal opportunities to just run into each other to lower the barriers for personal exchanges.

→ Choose your context.

This sometimes is neglected, but try to choose wisely where you and your team plan to work. Working on location at your client’s office will be different than just visiting every now and again. When do you need to limit external exposure? When do you need the (informal) exchange? 103

→ Deal with unavoidable conflicts in a timely manner.

You will find that the service design approach has many built-in strategies that help you to avoid conflicts in the first place. You can find them in the overall approach (e.g., the strategic use of boundary objects or prototypes for communication and development of a shared understanding, and the iterative nature of the process to reduce risks) as well as in specific toolsets. 104

Conflicts that are more emotional or arise from interpersonal relationships (“I just cannot stand that guy!”) are harder to tackle and usually require a different skill set. Hence, in the long term, consider training your team in conflict resolution up front. That allows them to quickly notice and resolve conflicts themselves before they interfere with the atmosphere in the team. Consult with a professional mediator on how you should proceed or check the conflict resolution literature for an overview on available options. 105

Onboarding and communicating with co-creators

Co-creation is at the heart of service design. Over the course of a project you might need to onboard many people to your extended project team. Make sure you plan for this, as it takes time. You might need to get permission before you can invite or work with people from other departments or external experts. In any case, almost everybody needs lead-in time to make space in their own schedule for your project. The people you might want to work with are probably not sitting around doing nothing and waiting for you to call. You even might have to get through their natural defense mechanisms (“Oh, another project …”) before they will commit themselves to join your process – even if it is just for one workshop.

True co-creation means you also need to create and maintain a sense of co-ownership with your co-creators beyond their direct involvement. This implies that they are not just involved but can also see or at least sense the impact of their own contributions later on. Try to regularly update your co-creators on what is happening. This, in turn, ensures buy-in. There is a real danger in a “co-create-and-forget” mentality. Buy-in will only work if you keep people in the loop and give them the opportunity to see and experience the effects of their own contributions.

Be aware, however, that you still need to carefully manage expectations during your co-creation sessions so everyone understands that not all contributions will make it into concepts or prototypes, let alone the eventual service solution.

Regardless of how small the contribution is and whether it is used later or not, it is always good practice to track it and give credit. In its simplest form, this involves keeping lists of participants for all the activities you do during your process. Decide how you want to and can best give credit in your project – considering the realities within your organization – so it is actually meaningful to your participants.

Expert Tip

Expert Tip

“Onboarding is important, but its also worth thinking about a possible future where you will not be so centrally involved in the project. Make sure …that you have managed to hand over all of the key premises and findings for a successful project during your project communication. Many of these are unspoken in a project, and lead the project to go off in undesirable directions once you have left.”

— Simon Clatworthy

Iteration review

In an iteration review, you step back and reflect on what happened during your last iteration(s). You try to make sense of what you learned, create options for what you would like to do, and make decisions on how to make necessary changes to move forward. Typically, iteration reviews will be combined with planning the next iteration.

Content reviews

At many steps in your service design process, you need to do a content review – that is, reflect on the quality of your outputs and make decisions based on that. Many of the core activities of service design have those key reflective elements already built in. In research, have a look at methods of data synthesis and analysis. 106 In ideation, especially check out the pre-ideation methods or any methods on selecting ideas. 107 And for prototyping, there is reflection mainly in the evaluative prototyping methods and subsequent synthesis and analysis stages. 108

Content reviews are usually done by the core project team together with selected stakeholders from the extended team. It can be useful to include an additional content review as part of your iteration review session before moving on to the team retrospective.

Team retrospectives

You also need to address your learnings on the process itself, your mindset, and the quality of your collaboration within the core or extended project team. This is done during team retrospectives, usually carried out within the core project team.

There are many ways to do an effective retrospective of past iterations, and there are many useful questions you can ask. See the textbox Conducting a team retrospective for one common approach. 109 In a project with people working full-time, a more formal iteration review should be done at least every couple of weeks.

Unless there is an escalation or your project sponsor requests formal documentation, your iteration planning and any of your intermediate documentation can usually be quite rough. Create visual notes on flipcharts that everyone writes on simultaneously or take photos of your sticky notes. It’s important that you do it and learn from it. But do not try to make it pretty – it will change again too soon.

Examples: Process Templates

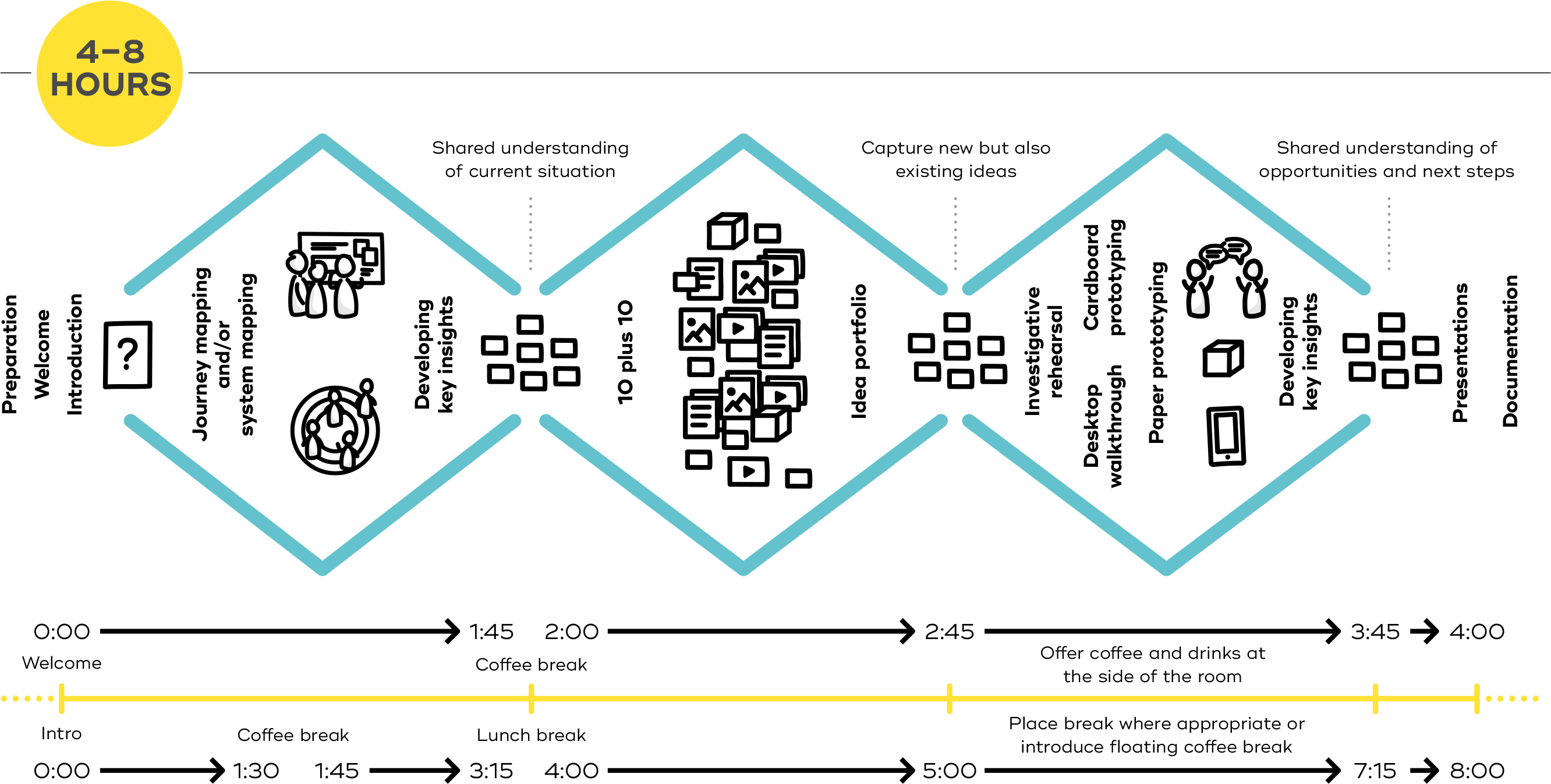

Figure 9-14. FOUR- TO EIGHT-HOUR INTRODUCTION WORKSHOP

The shorter the format, the more detailed your plan can be. Workshops like this allow you to engage with stakeholders and can be used to kick off a project or act as an initial preparatory iteration for bigger projects or workshops.

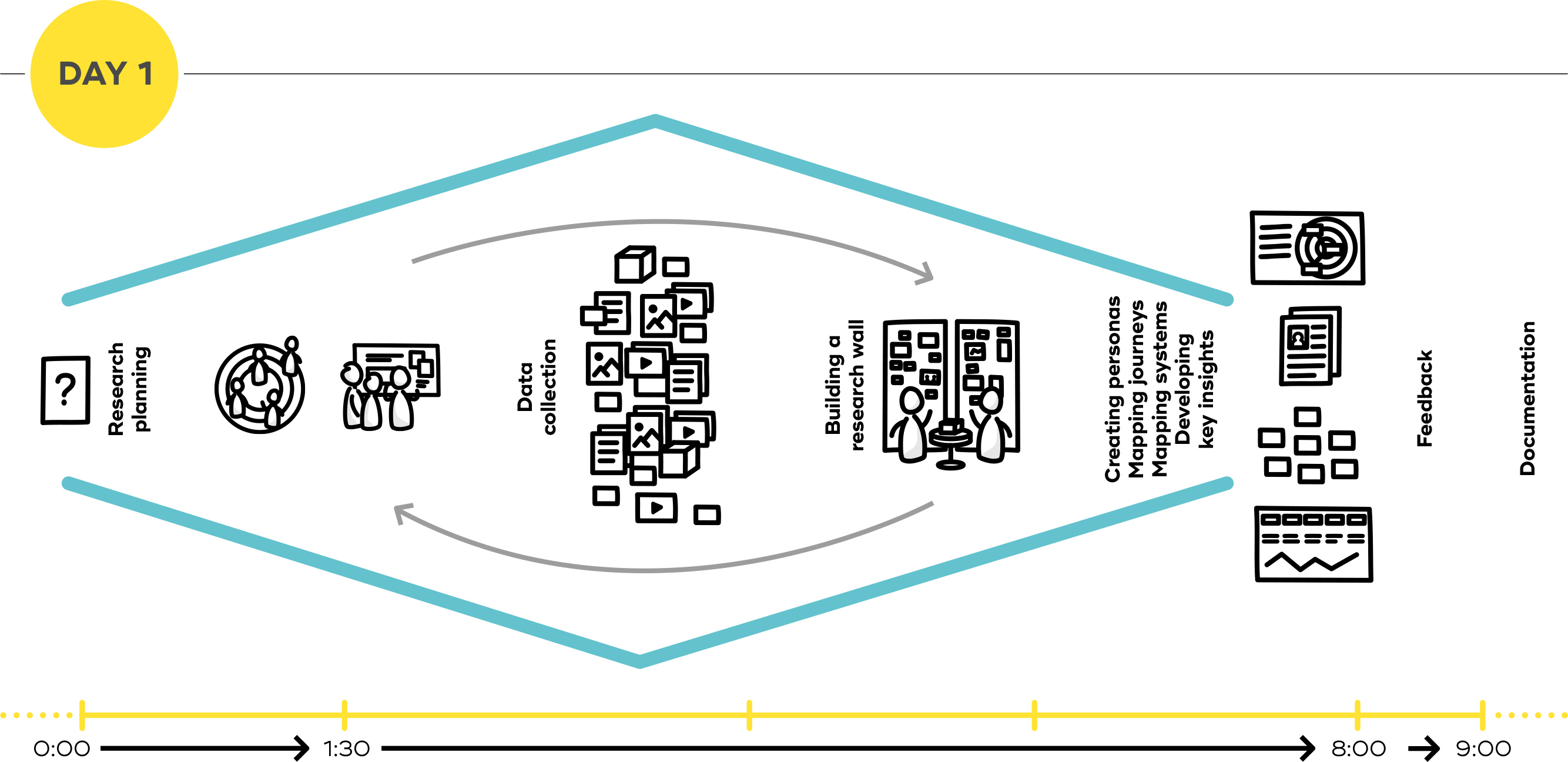

Figure 9-15. THREE-DAY SERVICE DESIGN SESSION

Compared to the short four- to eight-hour introduction, there is more time for actual iterations, especially within research, prototyping, and testing. In this example setup you can see the emphasis on customer-focused tools and methods.

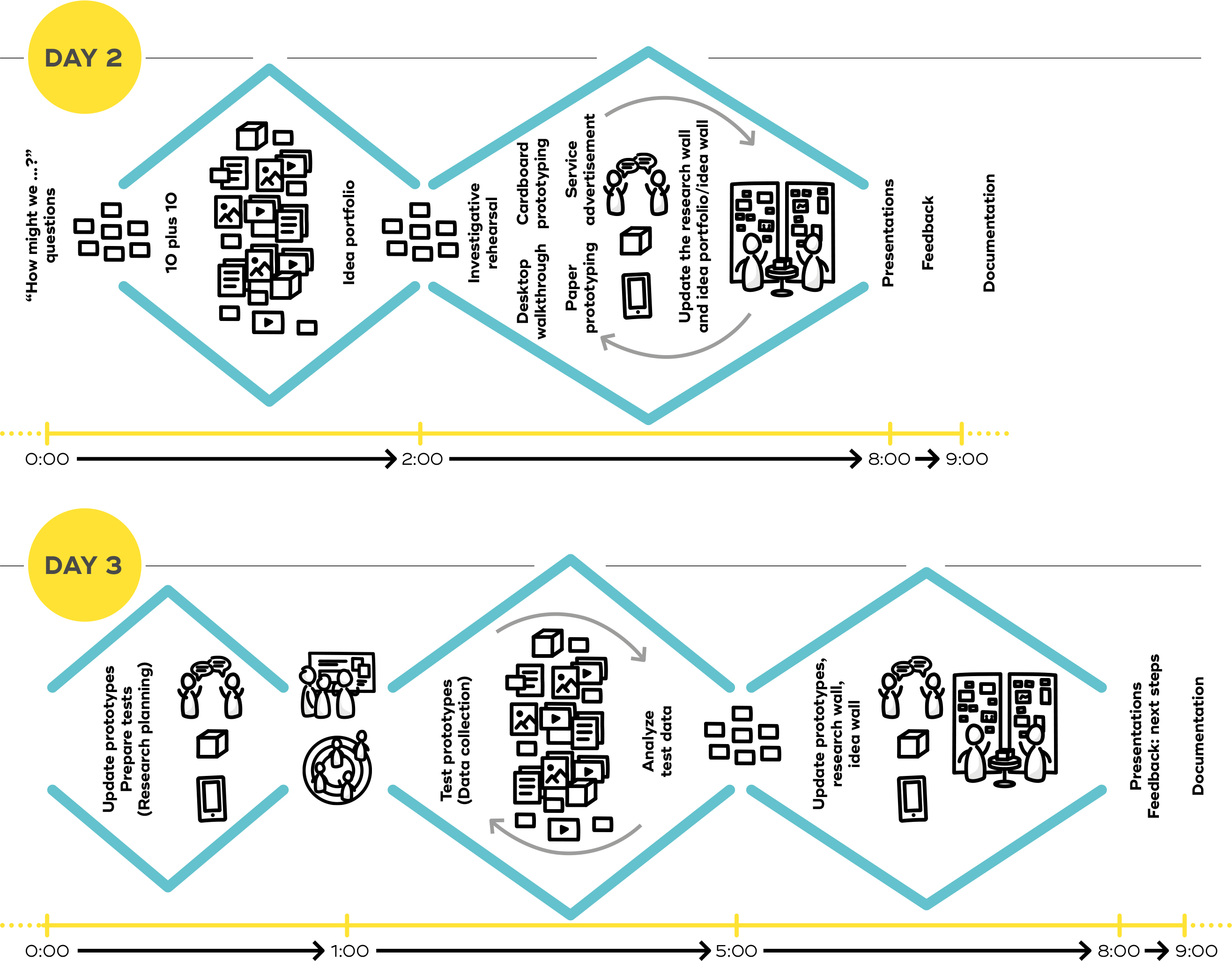

Figure 9-16. FIVE-DAY SERVICE DESIGN ITERATION

Structurally, this is similar to the three-day variant, but with more iterations and depth during research, prototyping, and testing. It also creates a clearer business view with the addition of service blueprints and/or the Business Model Canvas on the last day. 114

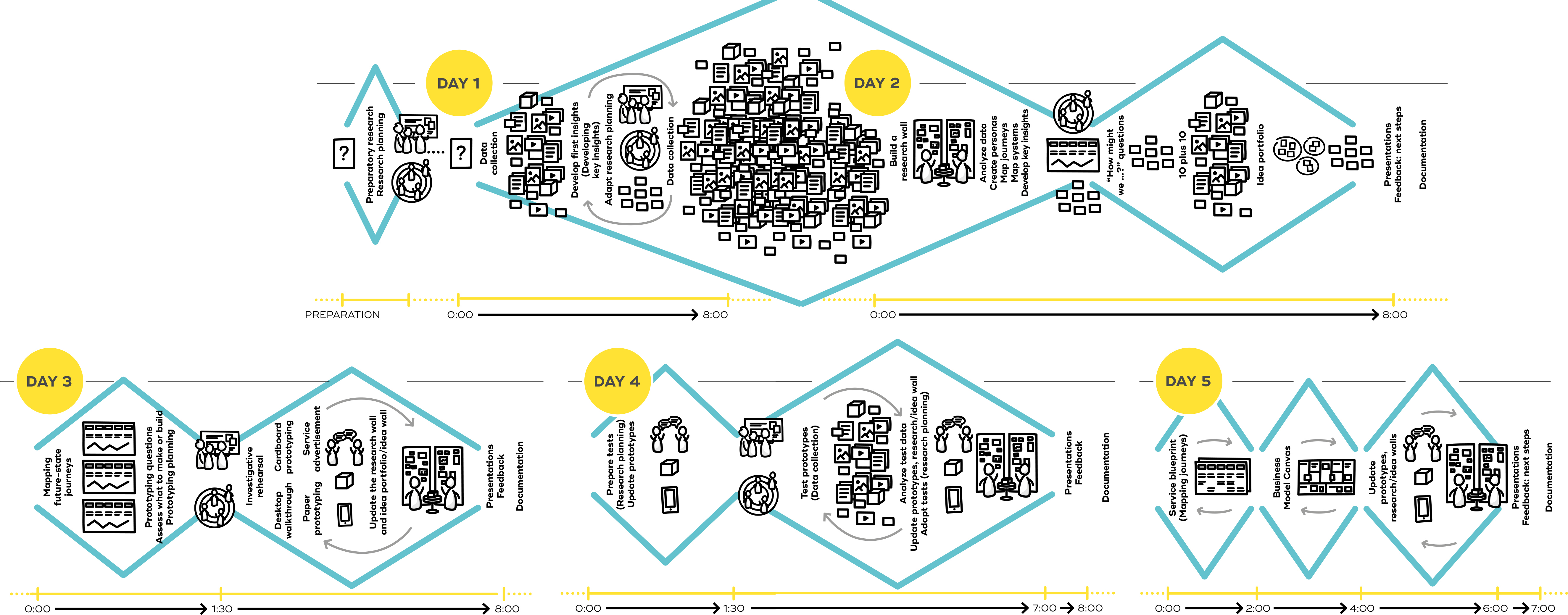

Figure 9-17. THREE-MONTH STRATEGIC SERVICE DESIGN PROJECT

Your planning and timing will vary, depending heavily on the actual brief, your stakeholders, strategic perspectives, previous projects, etc. Managing longer design projects requires experience and expertise with the design approach, the ecosystem you are working in, and the subject matter. 115

Cases

The three case studies in this chapter specifically show how service design processes can be structured differently in practice across different scopes and industries: how to create repeatable processes to continually improve services and experiences at massive scale (“Case: Creating Repeatable Processes to Continually Improve Services and Experiences at Massive Scale”), how to manage strategic design projects (“Case: Managing Strategic Design Projects”), and how to use a five-day service design sprint structure to create a shared cross-channel strategy (“Case: Using a Five-Day Service Design Sprint to Create a Shared Cross-Channel Strategy”).

-

- — Alex Nisbett, Service Designer, Spectator Experience, London Organizing Committee of the Olympic and Paralympic Games

9.5.2 Case: Managing strategic design projects

- — Marta Sánchez Serrano, Head of Commercial Strategy and Operations, Vodafone

- — Jesús Sotoca, Consultant and Strategic Design Director, Designit

9.5.3 Case: Using a five-day service design sprint to create a shared cross-channel strategy

Itaú’s design challenge: New brand’s tone of voice for digital channels

- — Clarissa Biolchini, Design Consultant and Service Design Specialist, Laje

Case: Creating Repeatable Processes to Continually Improve Services and Experiences at Massive Scale

Continual improvement of the Olympic spectator experience (when you know it won’t be right on day one)

AUTHOR

Alex Nisbett Service Designer, Spectator Experience, London Organizing Committee of the Olympic and Paralympic Games

When it finally came to game time, the organizers of the London 2012 Olympic and Paralympic Games were clear on one thing: that it wouldn’t be right on day one. Or day two, or even day three. In fact, they were well prepared for things to go wrong (they did), and understood the value of continual improvement of the spectator experience.

As part of the team who designed and delivered the spectator experience at London 2012, one of my roles as Games time approached was to design for, and then support this continual improvement.

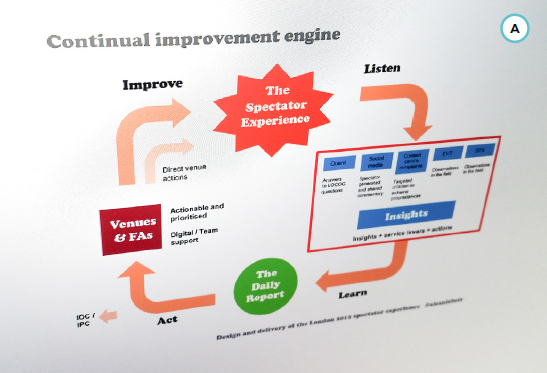

We created a simple, repeatable process to help identify the positive and negative experiences across the Games, which could be shared with venue and functional teams to help them make improvements to the services they were providing to the 12+ million spectators who made it to the Games:

1 Listen

Our research team had already planned daily questionnaires, some of which were conducted as exit interviews as spectators left venues after their events; more were delivered via email. The results of this research helped us generate a hotspot map showing where the main pain points were across the venues, along with numbers showing how venues were performing relative to each other. A healthy sense of competition between venues seemed totally appropriate!

Qualitative and quantitative

Observations from members of the spectator experience team in and around the venues combined with plain common sense from the venue teams helped us to define more exactly what the problems were and why they were happening. Additional detail also came from monitoring of social media (the use of geolocation tagging meant we didn’t need tweets to include the name of the venue).

2 Learn

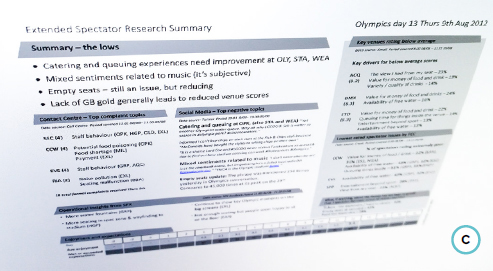

With so much data from so many sports and venues, daily analysis and synthesis was critical to help us create a high-level daily report (see the image) for senior stakeholders, plus additional details for the venue and functional area (FA) teams to help them make improvements. What we saw as the daily challenges and continued threats to the spectator experience (the insights) were matched up to practical and achievable improvements and mitigations (the service levers) to create a number of actions which we believed would make a difference.

Daily report

The daily report delivered to the main operations center also included scores, ratings, and rankings to help identify the high and low performers, plus overall trends across the Games. The very highest scores were in fact on the days when Team GB won medals and when the weather was at its best, proving that sometimes there is more to an experience than what can be designed into it.

The continual improvement engine operated each and every day of the games, involving multiple teams in the creation of data, analysis, reporting, and finally taking action to improve the spectator experience.

Hot spot maps showing relative high and low performers were created each day using data from exit interviews and online questionnaires about the spectator experience in and around venues.

A daily report created by analyzing detailed research results for each sporting venue and functional area helped those at the main operations center, and senior stakeholders, to quickly understand how well we were performing.

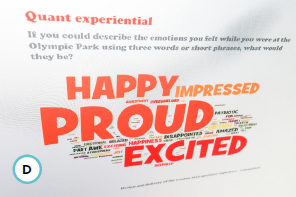

A simple word cloud created from responses to one of the questionnaire prompts allowed us to see at a glance how spectators were really feeling. 116

3 Act

Tangible actions, including their operational details, were refined and then prioritized by venue and FA leadership, before being shared with the teams on the ground who would implement them. These actions included changes to what already existed (e.g., adjusted behaviors for frontline staff, or additional water fountains as well as completely new additions (temporary digital signage to support new “day pass” ticketing, or the design and construction of Mascot House for the Paralympics).

Prototype early

Most teams were actually really well prepared for the changes they were asked to make; in fact, each and every team had previously run a test event (a prototype in service design speak) and they were used to learning and improving. Some teams were less able to make the changes required of them in order to increase their satisfaction scores – notably the catering team.

4 Improve

A sense of realism and pragmatism among the teams helped, and we were very clear that things “wouldn’t be right” from the start. This healthy attitude meant that we were able to focus on continued and sustained improvement from Opening to Closing Ceremony, and across the transition from Olympics to Paralympics. In many ways, the Olympics were seen as a warm-up for the “Paras,” and indeed, the Paralympics benefited from lessons learned a few weeks earlier.

Spectator satisfaction (met or exceeded expectations) rose from 90% on day one to 96% at the end of the Games. The spectator experience team could not claim responsibility for this, nor could service design alone as at the end of the day, spectators were there for the athletes and to be a part of the “greatest show on Earth.” If they had to queue to get into the venue or for their fish and chips, that wasn’t so bad, as spectators, especially those accustomed to large-scale events, were prepared for that. It is the Olympics, after all.

However, improving the spectator experience continually, knowing that even the last day would be someone’s first day, was what we had all signed up for.

Key Takeaways

01 Accept that services and experiences will never be perfect and can be continually improved. Each and every day sees customers getting their first and (so the song goes) lasting impression. Don’t miss your chance to make a difference.

02 Spend time on the front line watching and listening. Become part of customer-facing teams, even for just a day. Know what it’s like to deliver a service. Make customer experience everyone’s responsibility.

03 Define a deadline – create a sense of urgency, focus, and real purpose. We were regularly reminded how many “days to go” there were until Games time. This was initially motivating but subsequently frightening!

04 Everything can be prototyped, even sports events of Olympic proportions.