Chapter 19. Sharing Files on the Network

Almost every Windows machine on earth is connected to the Mother of All Networks, the one we call the Internet. But most PCs also get connected, sooner or later, to a smaller network—some kind of home or office network.

If you work at a biggish company, then you probably work on a domain network—the centrally managed type found in corporations. In that case, you won’t have to fool around with building or designing a network; your job, and your PC, presumably came with a fully functioning one (and a fully functioning geek responsible for running it).

Within your home or small office, though, you can create a smaller, simpler network that you set up yourself.

In either case, being on a network means you can share all kinds of stuff among the various PCs that are connected:

Files, folders, and disks. No matter what PC you’re using on the network, you can open the files and folders on any other networked PC, as long as the other PCs’ owners have made those files available for public inspection. That’s where file sharing comes in, and that’s what this chapter is all about.

The uses for file sharing are almost endless. It means you can finish writing a letter in the bedroom, even if you started it downstairs at the kitchen table—without having to carry a flash drive around. It means you can watch a slideshow drawn from photos on your spouse’s PC somewhere else in the house. It means your underlings can turn in articles for your company newsletter by depositing them directly into a folder on your laptop.

Tip:

File sharing also lets you access your files and folders from the road, using a laptop. See Chapter 12 for more information on this road-warrior trick.

Music and video playback. Windows Media Player can stream music and videos from one PC to another on the same network—that is, play in real time across the network, without your having to copy any files. In a family situation, it’s super-convenient to have Dad’s Mondo Upstairs PC serve as the master holding tank for the family’s entire music collection—and be able to play it using any PC in the house.

Printers. All PCs on the network can share a printer. If several printers are on your network—say, a high-speed laser printer for one computer and a color printer on another—then everyone on the network can use whichever printer is appropriate for a particular document. Step-by-step instructions start in “Fancy Printer Properties”.

Note:

Your network might include a Windows 10 PC, a couple of Windows 7, 8, XP, or Vista machines, older PCs, and even Macs. That’s perfectly OK; all these computers can participate as equals in this party. This chapter points out whatever differences you may find in the procedures.

Kinds of Networks

You can connect your PCs using any of several different kinds of gear:

Ethernet is a wired networking system—the world’s most popular. An Ethernet jack, for an Ethernet cable, is built into virtually every desktop PC and many laptops. That’s your network adapter—the circuitry that provides the Ethernet jack (Figure 19-1). If your machine doesn’t have an Ethernet jack—tablets don’t, and slim laptops usually don’t—you can add one. Adapters are available as internal cards, external USB attachments, or laptop cards.

Tip:

If you’ve got a computer that sits in one place, like a desktop PC, then you should use an Ethernet cable even if you have a wireless network.

One reason is security (wired networks are harder for the baddies to “sniff”). Another is speed. Yes, wireless technologies like 802.11ac and ax promise superfast speeds. But, first of all, the real-world speed is about a third of their published maximums; second, that speed is shared among all computers on the network. As a result, if you’re copying a big file across the network, it will probably go twice as fast if it’s going between one wireless and one wired PC than between two wireless PCs.

Wi-Fi, of course, means wireless networking. Every computer sold today has a Wi-Fi antenna built in. Wireless networking is not without its downsides. Big metal things, or walls containing big metal things (like pipes) can interfere with communication among the PCs, much to the disappointment of people who work in subways and meat lockers.

A wireless network isn’t as secure as a cabled network, either. It’s theoretically possible for some hacker, sitting nearby, armed with “sniffing” software, to intercept the email you’re sending or the web page you’re downloading. (Except secure websites, those marked by a little padlock in your web browser.)

Still, nothing beats the freedom of wireless networking, particularly if you’re a laptop lover; you can set up shop almost anywhere in the house or yard, slumped into any kind of rubbery posture. No matter where you go within your home, you’re online at full speed, without hooking up a single wire.

Phone line networks. Instead of going to the trouble of wiring your home with Ethernet cables, a few people use the wiring that’s already in the house—telephone wiring. That’s the idea behind a kind of networking gear called HomePNA. Unfortunately, the average American household has only two or three phone jacks in the entire house—and these days your house may have none at all— meaning you don’t have much flexibility in positioning your PCs.

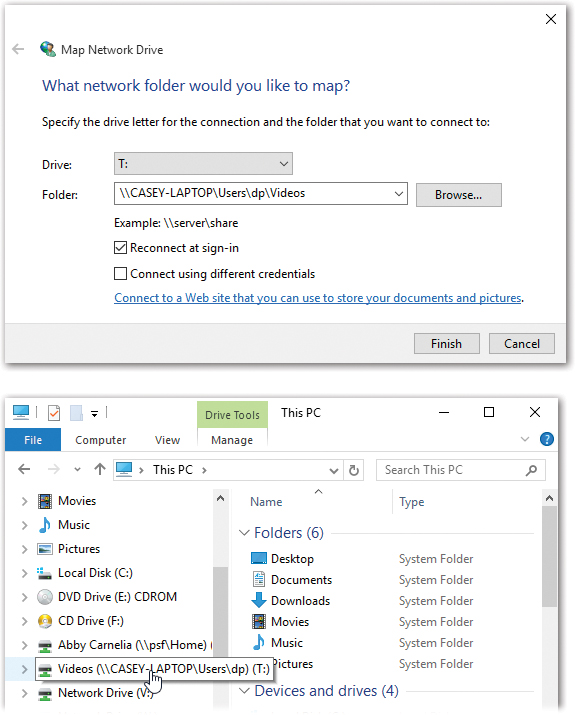

Figure 19-1. Top: The Ethernet cable is connected to a computer at one end, and the router (shown here) at the other end. The computers communicate through the router; there’s no direct connection between any two computers. The front of the router has little lights for each connector port, which light up only on the ports in use. You can watch the lights flash as the computers communicate.

Bottom: Here’s what a typical “I’ve got three PCs in the house, and I’d like them to share my cable modem” setup might look like.Power outlet networks. Here’s another way to connect your computers without rewiring the building: Use the electrical wiring that’s already in your walls. If you buy Powerline adapters (also called HomePlug adapters), you get decent speeds (from 14 Mbps up to 100 Mbps), very good range (1,000 feet), and the ultimate in installation simplicity. You just plug the Powerline adapter from your PC’s Ethernet or USB jack into any wall power outlet. Presto—all the PCs are connected.

File Sharing 1: Nearby Sharing

Setting up file sharing traditionally requires a lot of steps.

In the original editions of Windows 10, Microsoft attempted to simplify the process by creating something called HomeGroups.

Alas, HomeGroups weren’t quite simple enough. They baffled most customers so much that, in the April 2018 Update, Microsoft eliminated them. (The HomeGroups, not the customers.)

But the April 2018 Update includes a new feature called Nearby Sharing, which is a loving homage (or maybe a shameless ripoff) of a Mac feature called AirDrop.

Nearby Sharing is a breakthrough in speed, simplicity, and efficiency. There’s no setup, no passwords, nothing to email. It lets you transmit files or links to someone else’s PC up to 30 feet away, instantly and wirelessly. You don’t even need an Internet connection; it works on a flight, a beach, or a sailboat in the middle of the Atlantic. It also works if you’re on a Wi-Fi network, doing other things online.

The one catch is that Nearby Sharing works only among PCs that have the April 2018 Update (or a later version) of Windows.

Nearby Sharing Setup

To get things ready, open ![]() →

→![]() →System→“Shared experiences.” Here you have three choices to make.

→System→“Shared experiences.” Here you have three choices to make.

Nearby sharing on/off. Shocker: The feature doesn’t work unless it’s turned on.

Tip:

There’s also an on/off tile for Nearby Sharing on the Action Center (“The Action Center”), for your convenience.

I can share or receive content from. Your choices are “Everyone nearby” (including total strangers, by the way) or “My devices only” (you’ll use it only for moving files and photos among your own machines—computers that are signed into the same Microsoft account).

Paranoid note: If you choose “Everyone nearby,” it’s true that total strangers could mischievously attempt to send you files. But it’s also true that when a “Do you want to accept?” notification appears on your screen, you can always just hit Decline.

Save files I receive to. Where do you want incoming files to go? Windows, of course, proposes your Downloads folder.

All right: You’re ready to use Nearby Sharing.

Sending a File with Nearby Sharing

You begin the sending process from Windows 10’s modern Share button, which is usually marked by a ![]() . You’ll find it in two general places: at the desktop and in your apps. Here’s how you send stuff using Nearby Sharing:

. You’ll find it in two general places: at the desktop and in your apps. Here’s how you send stuff using Nearby Sharing:

Start in a File Explorer window. Right-click a file’s icon. From the shortcut menu, choose Share. The Share panel appears, as shown in Figure 19-2. (See “UP TO SPEED The Share Panel” for more on the Share panel.)

After a moment, the icons of any other Windows 10 machines show up, as shown in Figure 19-2. (Well, at least any others that are turned on, have Nearby Sharing turned on, and are within range.)

Note:

If you don’t have Nearby Sharing turned on, then the middle panel of the Share panel says “Tap to turn on nearby sharing.” Click or tap that message to get started.

Select the icon of the PC you want to receive the file you’re trying to send.

Start in an app. Nearby Sharing is also available in any app that bears a Share button (

), and therefore has the Share panel. That includes Photos (send pictures or videos), Edge (send links), News (send articles), Paint 3D (send your artwork), People (send someone’s contacts “card”), and Maps (send whatever place or directions you’re looking at).

), and therefore has the Share panel. That includes Photos (send pictures or videos), Edge (send links), News (send articles), Paint 3D (send your artwork), People (send someone’s contacts “card”), and Maps (send whatever place or directions you’re looking at).

Either way, a notification lets you know the other PC has yet to accept (Figure 19-2, top).

In a moment, a message appears on the other PC’s screen, asking if the owner wants to accept your file (Figure 19-2, lower left). That person can choose either Save (to save the file to that PC’s Downloads folder), Save & Open (which also opens the file), or Decline.

If the receiver opts for one of the Save buttons, then after a moment, the transaction is complete. Quick, effortless, wireless, delightful.

Figure 19-2. Top: You’re sending a file from a File Explorer window to another PC called MonsterAsus. When you choose its name in the Share panel, Windows lets you know it’s waiting for the other guy to accept (inset, top).

Bottom: On the MonsterAsus machine, a notification (left) lets you know that the SurfacePro is trying to send you a file wirelessly. You can save the incoming file, save and open it, or decline. If you hit Save, then after the transfer, a “Receiving complete” notification appears (lower right).

Deep-Seated Networking Options

If you’re perusing the ![]() →

→![]() →Network & Internet→Wi-Fi settings one day, and you scroll down to “Related settings,” you might wonder about some of the technical links listed here. In general, the average person isn’t supposed to need these; they’re all holdovers from much older, much fussier editions of Windows. But just in case you need them someday, here’s the rundown of what they do.

→Network & Internet→Wi-Fi settings one day, and you scroll down to “Related settings,” you might wonder about some of the technical links listed here. In general, the average person isn’t supposed to need these; they’re all holdovers from much older, much fussier editions of Windows. But just in case you need them someday, here’s the rundown of what they do.

Change Adapter Options

Click this link to view a list of all your network adapters—Ethernet cards and Wi-Fi adapters, mainly—as well as any VPNs or dial-up connections you’ve set up on your computer.

Double-click a listing to see its connection status, which leads to several other dialog boxes where you can reconfigure the connection or see more information. The toolbar offers buttons that let you rename, troubleshoot, disable, or connect to one of these network doodads.

Note:

If you right-click one of these icons and then choose Properties, you get a list of protocols that your network connection uses. Double-click “Internet Protocol Version 6” to tell Windows whether to get its IP and DNS server addresses automatically, or whether to use addresses you’ve specified. Ninety-nine times out of 100, the right choice is to get those addresses automatically. Every once in a while, though, you’ll come across a network that requires manually entered addresses.

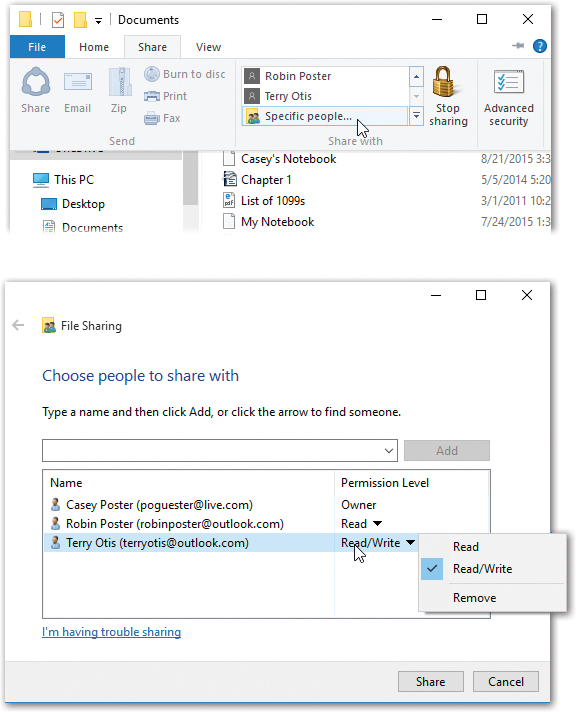

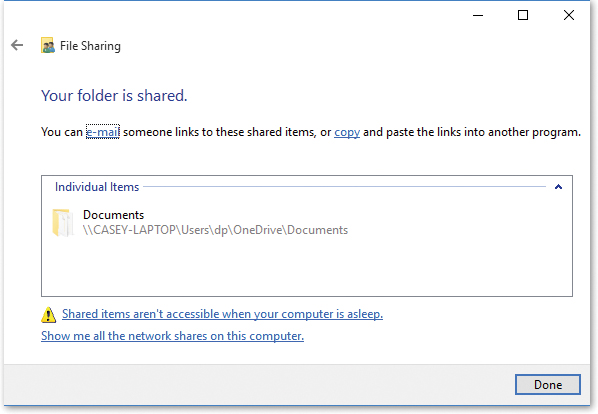

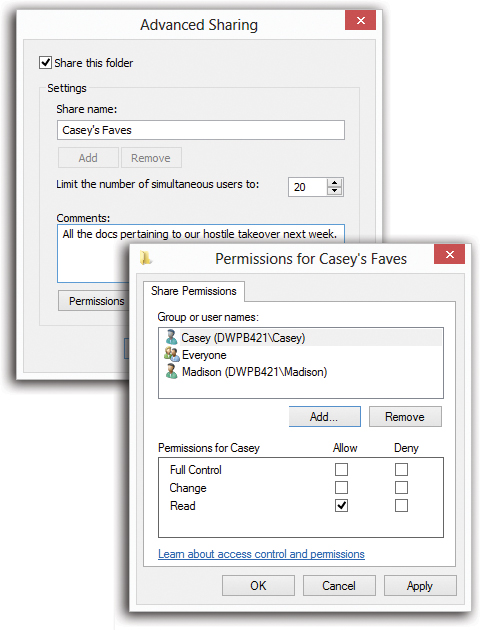

Change Advanced Sharing Settings

This section is the master control panel of on/off switches for Windows’ network sharing features. (Most of these have on/off switches in other, more scattered places, too.) Here’s a rundown.

Note:

The options here are actually listed three times: once for Private networks (your own home or office networks), once for Public ones (coffee shops and so on), and once for All networks.

Network discovery makes your computer visible to others and allows your computer to see other computers on the network.

File and printer sharing lets you share files and printers over the network. (See “Printing”.)

Public folder sharing lets you share whatever files you’ve put in the Users

Public folder. (See “Accessing Shared Folders”.)

Public folder. (See “Accessing Shared Folders”.)Media streaming is where you listen to one PC’s music playing back over the network while seated at another (see “Kinds of Networks”). It appears here only if you’ve turned this feature on.

File sharing connections lets you turn off the super-strong security features of Windows file sharing, to accommodate older gadgets that don’t recognize it.

Password protected sharing is an on/off switch. When it’s on, the only people who can access your shared folders and printers are those who have accounts on your PC. When it’s off, anybody can access them. Details are in “File Sharing 2: “Share a Folder””.

The Network and Sharing Center

The Network and Sharing Center used to be the master control center for creating, managing, and connecting to networks of all kinds (Figure 19-8). Now that you can do most network tasks right in the Settings app, the NaSC isn’t quite as essential.

To do anything with your network, you need to click one of the links in blue. They include these.

Set up a new connection or network

Most of the time, Windows does the right thing when it encounters a new network. For example, if you plug in an Ethernet cable, it assumes you want to use the wired network and automatically hops on. If you come within range of a wireless network, Windows offers to connect to it.

Some kinds of networks, however, require special setup:

Connect to the Internet. Use this option when Windows fails to figure out how to connect to the Internet on its own. You can set up a Wi-Fi, PPPoE broadband connection (required by certain DSL services that require you to sign in with a user name and password), or even a dial-up networking connection.

Set up a new network. You can use this option to configure a new wireless router that’s not set up yet, although only some routers can “speak” to Windows in this way. You’re better off using the configuration software that came in the box with the router.

Figure 19-8. Once it’s open, the Network and Sharing Center offers links that let you connect to a network, create a new network, troubleshoot your connection, fiddle with your network or network adapter card settings, and so on.

Manually connect to a wireless network. Some wireless networks don’t announce (broadcast) their presence. That is, you won’t see a message popping up on the screen, inviting you to join the network, just by wandering into it. Instead, the very name and existence of such networks are kept secret to keep the riffraff out. If you’re told the name of such a network, use this option to type it in and connect.

Connect to a workplace. That is, set up a secure VPN connection to the corporation that employs you, as described in “Virtual Private Networking”.

Troubleshoot problems

Very few problems are as annoying or difficult to troubleshoot as flaky network connections. With this option, Microsoft is giving you a tiny head start.

When you click “Troubleshoot problems,” Windows asks what, exactly, you’re having trouble with. Click the topic in question: Internet Connections, Shared Folders, and so on. Invisibly and automatically, Windows performs several geek tweaks that were once the realm of highly paid networking professionals: It renews the DHCP address, reinitializes the connection, and, if nothing else works, turns the networking card off and on again.

If the troubleshooter doesn’t pinpoint the problem, check that all the following are in place:

Your cables are properly seated in the network adapter card and hub jacks.

Your router, Ethernet hub, or wireless access point is plugged into a working power outlet.

Your networking card is working. To check, open the Device Manager (type its name at the Start menu). Look for an error icon next to your networking card’s name. See Chapter 15 for more on the Device Manager.

If that doesn’t fix things, you’ll have to call Microsoft, your PC maker, or your local teenage PC for help.

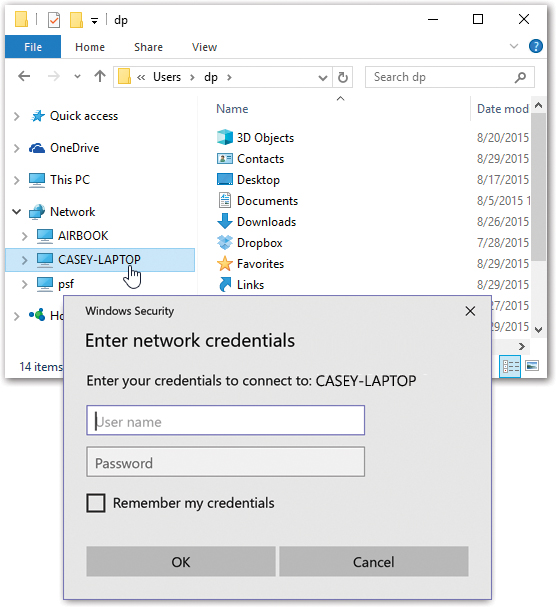

Corporate Networks

Connecting to other machines in your house or small office is one thing. In huge companies, though, the ones that are Microsoft’s bread and butter, networking is a full-time job—for a whole staff of people. These are the network administrators, who have studied the complexities of corporate networking for years. And their work—the sprawling, building-wide (or even worldwide) company networks—are called domain networks.

The Domain

On a regular small-office network, nobody else on a workgroup network can access the files on your PC unless you’ve created an account for them on your machine. Whenever somebody new joins the department, you have to create another new account; when people leave, you have to delete or disable their accounts. If something goes wrong with your hard drive, you have to recreate all of the accounts.

If you multiply all of this hassle by the number of PCs on a growing network, it’s easy to see how you might suddenly find yourself spending more time managing accounts and permissions than getting any work done.

The solution is the network domain. In a domain, you have only a single name and password, which gets you into every shared PC and printer on the network that you’re authorized to use. Everyone’s account information resides on a central computer called a domain controller—a computer so important, it’s usually locked away in a closet or a data-center room.

Most domain networks have at least two domain controllers with identical information, so if one computer dies, the other one can take over. (Some networks have many more than two.) This redundancy is a critical safety net, because without a happy, healthy domain controller, the entire network is dead.

Without budging from their chairs, network administrators can use a domain controller to create new accounts, manage existing ones, and assign permissions. The domain takes the equipment-management and security concerns of the network out of the hands of individuals and puts them into the hands of trained professionals.

If you use Windows in a medium- to large-sized company, you probably use a domain every day. You may not have been aware of it, but that’s no big deal; knowing what’s going on under your nose isn’t especially important to your ability to get work done.

Note:

One key difference between the Home and Pro versions of Windows 10 is that computers running the Home edition can’t join a domain.

Active Directory

One key offering of these big networks—and the Windows Server software that runs them—is an elaborate program called Active Directory. It’s a single, centralized database that stores every scrap of information about the hardware, software, and people on the network.

Active Directory lets network administrators maintain an enormous hierarchy of computers. A multinational corporation with tens of thousands of employees in offices worldwide can all be part of one Active Directory domain, with servers distributed in hundreds of locations, all connected by wide-area networking links. (A group of domains is known as a tree. Huge networks might even have more than one tree; if so, they’re called—yes, you guessed it—a forest.)

Unless you’ve decided to take up the rewarding career of network administration, you’ll never have to install an Active Directory domain controller, design a directory tree, or create domain objects. However, you very well may encounter the Active Directory at your company. You can use it to search for the mailing address of somebody else on the network, for example, or locate a printer that can print on both sides of the page at once. Having some idea of the directory’s structure can help in these cases.

Three Ways Life Is Different on a Domain

The domain and workgroup personalities of Windows are quite different. Here are some of the most important differences.

Logging in

What you see when you sign into your PC is somewhat different when you’re part of a domain. The Lock screen instructs you to press Ctrl+Alt+Delete to sign in. (This step is a security precaution, described in the box below.)

You can now type your user name and password. To save you time, Windows fills in the User Name box with whatever name was used the last time somebody signed in.

Browsing the domain

When your PC is part of the domain, all of its resources—printers, shared files, and so on—magically appear in your desktop windows, the Network window, and so on.

Searching the domain

You can read all about the search box in Chapter 3. But when you’re on a domain, this tool becomes far more powerful—and more interesting.

When you open the Network window as described above, the Ribbon changes to include an option to Search Active Directory. Click it to open a special dialog box that can search the entire corporation at once.

Using this box, you can search for things like:

Users, Contacts, and Groups. Use this option to search the network for a particular person or network group. You can find out someone’s telephone number or mailing address, or see what people belong to a particular group.

Computers. This option helps you find a certain PC in the domain. It’s of interest primarily to network administrators, because it lets them manage many of the PCs’ functions by remote control.

Printers. In a large office, it’s possible you might not know where you can find a printer with certain features—tabloid-size paper, for example, or double-sided printing. That’s where this option comes in handy; it lets you find the printing features you need.