Chapter 3. Organizing & Finding Your Files

Every disk, folder, file, application, printer, and networked computer is represented on your screen by an icon. To avoid spraying your screen with thousands of overlapping icons seething like snakes in a pit, Windows organizes icons into folders, puts those folders into other folders, and so on. This folder-in-a-folder-in-a-folder scheme works beautifully at reducing screen clutter, but it means you’ve got some hunting to do whenever you want to open a particular icon.

Helping you find, navigate, and manage your files, folders, and disks with less stress and greater speed is one of the primary design goals of Windows—and of this chapter. The following pages cover Windows 10’s Search function, plus icon-management life skills like selecting them, renaming them, moving them, copying them, making shortcuts of them, assigning them to keystrokes, deleting them, and burning them to CD or DVD.

The Search Box

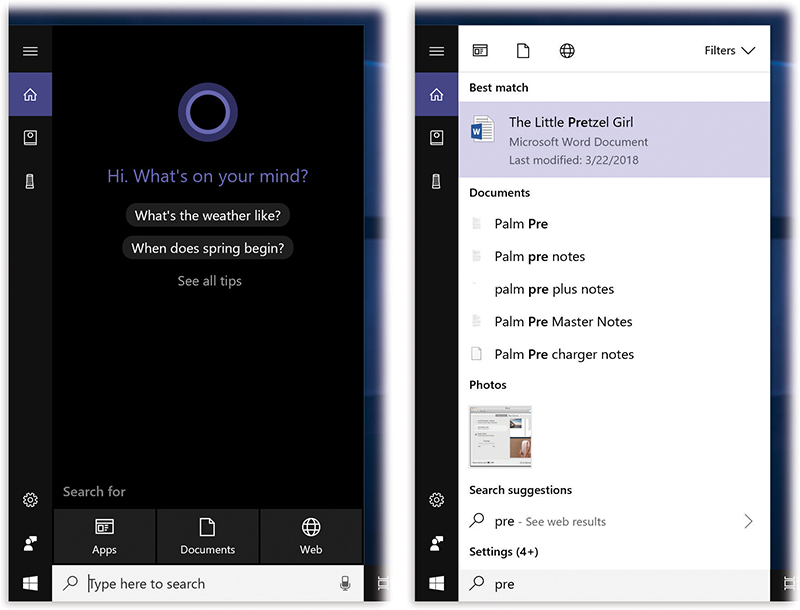

Every computer offers a way to find and open files and programs. And in Windows 10, the Search feature searches both your computer and the web simultaneously. And Microsoft has tried to mix together Search and Cortana, Windows’ voice-controlled assistant.

But at its heart, Search is still Search. It’s how you open an app, find a file, or adjust a setting just by typing a few letters. It can save you a lot of hunting and burrowing through your folders.

It’s important to note, though, that Windows offers search boxes in two different places:

The main search box. The search box at the left end of the taskbar— usually labeled “Type here to search”—searches everywhere on your computer. And beyond; it can also search your network or the Internet.

Tip:

Remember, if you don’t want to devote the taskbar space to Cortana, you can hide her. Right-click an empty space on the taskbar and choose Cortana→Show Cortana icon, which plants just her icon in the taskbar, or Cortana→Hide Search Box, which removes her from the taskbar completely.

So how are you supposed to search now? The Start menu. Just press ![]() and start typing your query. This searching method works essentially the same as what’s described on these pages.

and start typing your query. This searching method works essentially the same as what’s described on these pages.

File Explorer windows. The search box at the top of every desktop window searches only that window (including any folders within it).

Search boxes also appear in the Settings window, the Edge browser, Mail, and all the other spots where it’s useful to perform small-time, limited searches. The following pages, however, cover the two main search boxes, the ones that hunt down files and folders.

The Taskbar Search Box

The search box is always on the screen as part of the taskbar. Here’s how you might perform a search:

Get your insertion point into the search box. You can click or tap the box (Figure 3-1, left), or press either of these keystrokes:

opens the Start menu. But it also puts your blinking cursor into the search box.

opens the Start menu. But it also puts your blinking cursor into the search box. +S keystroke tells Cortana (Chapter 5) that you’re about to type a request. But in Windows 10, Cortana is part of Search, so

+S keystroke tells Cortana (Chapter 5) that you’re about to type a request. But in Windows 10, Cortana is part of Search, so  +S puts your cursor into the search box, just as you’d hope. Makes mnemonic sense, too: S stands for Search.

+S puts your cursor into the search box, just as you’d hope. Makes mnemonic sense, too: S stands for Search.If your laptop has what Microsoft calls a precision touchpad (a multitouch trackpad like the one on a Surface), you can also tap the trackpad with three fingers simultaneously to open the Cortana panel and pop your cursor into the search box. (You can adjust this gesture in Settings; see “Trackpad Settings”.)

Note:

The first time you use the search box, Windows displays a panel that informs you of the kind of information it needs to collect. Click “I agree” to continue—or see “Setting Up Cortana” to find out more about this data.

At this point, you can click either Apps, Documents, or Web to limit your search to those realms—but you can also do that kind of refinement after you do the search.

Start typing what you want to find (Figure 3-1, right).

For example, if you’re trying to find a file called “Pokémon Fantasy League.doc,” typing just pok or leag will probably work.

Capitalization doesn’t count, and neither do accent marks; typing cafe finds files with the word “café” just fine. (You can change this, however; see “File Types tab”.)

As you type, search results begin to appear in the space formerly occupied by the Start menu, grouped by category (Figure 3-1). This is a live, interactive search; that is, Windows modifies the menu as you type—you don’t have to press Enter after entering your search phrase.

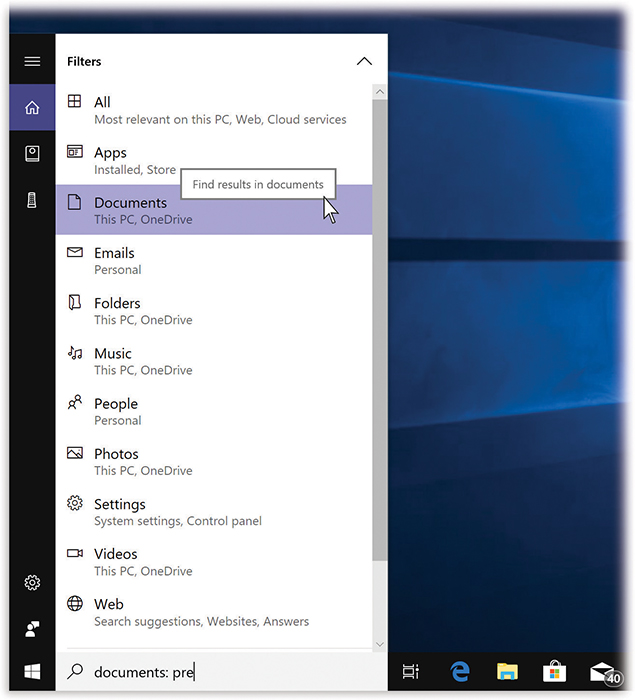

Figure 3-1. Left: “Type here to search” is your passport to searching your computer, network, OneDrive, and the web.

Right: You won’t always see your search term itself (“pre,” here) in the results list. That’s because Windows is also searching words inside the files. The matching result may be a word inside the text of a document, or even in the invisible tags associated with a file.The Search feature can find every file; folder; program; email message; address book entry; calendar appointment; picture; movie; PDF document; music file; web bookmark; and Word, PowerPoint, and Excel document that contains what you typed, regardless of its name or folder location.

In fact, Windows isn’t just searching icon names. It’s also searching their contents—the words inside your documents—as well as your files’ metadata. (That’s descriptive text information about what’s in a file, like its height, width, size, creator, copyright holder, title, editor, created date, and last modification date. “File Types tab” has the details.)

And it’s not just finding stuff on your PC. The results also include matches from whatever is on your OneDrive (“OneDrive”), apps on the Windows app store, and even websites found online by Microsoft’s Bing search service.

If you see the item you were hoping to dig up, tap or click to open it.

In fact, if that thing is listed first in the results menu, tinted, then you can press Enter to open it.

The search box, in other words, is an incredibly fast way to open a program you want. You should use it all the time. The whole thing happens very quickly, and you never have to take your hands off the keyboard. That is, you might hit

+S, type calc (to search for Calculator), and press Enter. (Why does pressing Enter open Calculator? Because it’s the first item in the list of results, and its name is highlighted.)

+S, type calc (to search for Calculator), and press Enter. (Why does pressing Enter open Calculator? Because it’s the first item in the list of results, and its name is highlighted.)Why burrow around in folders when you can open any file or program with a couple of keystrokes?

If the thing you want is not at the top of the list, click it, tap it, or “walk” down to it with the arrow keys, and then press Enter to open it.

Tip:

Unless you intervene (“Folder Options”), Search shows you results both from your computer and from the web, all in the same list. It takes an additional click to see only one or the other. Click

above the list to search just File Explorer,

above the list to search just File Explorer,  to search just your documents, or

to search just your documents, or  to open your browser and complete the search using Microsoft’s Bing search service.

to open your browser and complete the search using Microsoft’s Bing search service.If you don’t see what you’re looking for, click a category heading to see more results.

That step may take a little explanation; read on.

Filtering the Results

The search results menu has room for only a few items. Unless you own one of those rare 60-inch Skyscraper Displays, there just isn’t room to show you the whole list.

Instead, Windows uses some fancy analysis to display the most likely matches for what you typed. They appear grouped into categories like Apps, Settings, Folders, Documents, and Store (meaning apps from the Windows app store).

Such a short list of likely suspects means it’s easy to arrow-key your way to the menu item you want to open. And Windows does a pretty good job at guessing which two or three search results to show you in each category.

On the other hand, you might have 425 different documents containing the word “syzygy,” and you’ll see only three of them in the search-results list.

Fortunately, Windows offers four different ways to filter the list of results, so that it shows only the results in a certain category:

Click the category heading. Click the word Apps, or Settings, or Documents, or whatever. And boom: The list changes to show you only the search results in that category. Kind of handy, really.

Use the buttons at the top of the list. They limit the results to apps, documents, and the web, respectively. (You can see these buttons at right in Figure 3-1.)

Use the Filters drop-down menu at top right. It offers the complete list of categories you can use to limit the results: Apps, Documents, Emails, Folders, Music, People, Photos, Settings, Videos, or Web.

Use search shorthand. When you use any of the three methods described so far, you may notice something weird going on in the search box itself: New words appear there. If you search for kumquat and then click the Apps icon at top left, for example, the search box now says “apps: kumquat.” If you then click the Web icon, it changes to say “web: kumquat.” (You can see an example in Figure 3-2.)

Figure 3-2. Click a category heading to see more of the search results in that category.

You can filter your search results by just about every type of file by clicking the Filters drop-down menu.In other words, those clickable buttons and menus are just human-friendly ways of modifying your search query in the way Windows really understands: with search codes. Given that fact, there’s nothing to stop you from typing them manually. If you want to find a document called “Pretzel Recipe,” you can do a search for docs: pretzel (or documents: pretzel). If you’re hunting for a song called “Tie a Purple Ribbon,” you can just type music: purp or something.

The Search Index

You might think that typing something into the search box triggers a search. But to be technically correct, Windows has already done its searching. In the first hours after you install Windows—or after you attach a new hard drive—it invisibly collects information about all your files. Like a student cramming for an exam, it reads, takes notes on, and memorizes the contents of your hard drives.

And not just the names of your files. That would be so 2004!

No, Windows actually looks inside the files. It can read and search the contents of text files, email, Windows People, Windows Calendar, RTF and PDF documents, and documents from Microsoft Office (Word, Excel, and PowerPoint).

In fact, Windows searches over 300 bits of text associated with your files—a staggering collection of tidbits, including the names of the layers in a Photoshop document, the tempo of an MP3 file, the shutter speed of a digital-camera photo, a movie’s copyright holder, a document’s page size, and on and on. (Technically, this sort of secondary information is called metadata. It’s usually invisible, although a lot of it shows up in the Details pane described in “Tags, Metadata, and Properties”.)

Windows stores all this information in an invisible, multimegabyte file called, creatively enough, the index. (If your primary hard drive is creaking full, you can specify that you want the index stored on some other drive; see “Index Settings tab”.)

After that, Windows can produce search results in seconds. It doesn’t have to search your entire hard drive—only that card-catalog index file.

After the initial indexing process, Windows continues to monitor what’s on your hard drive, indexing new and changed files in the background, in the microseconds between your keystrokes and clicks.

Where Windows Looks

Windows doesn’t actually scrounge through every file on your computer. Searching inside Windows’ own operating-system files and all your programs, for example, would be pointless to anyone but programmers. All that useless data would slow down searches and bulk up the invisible index file.

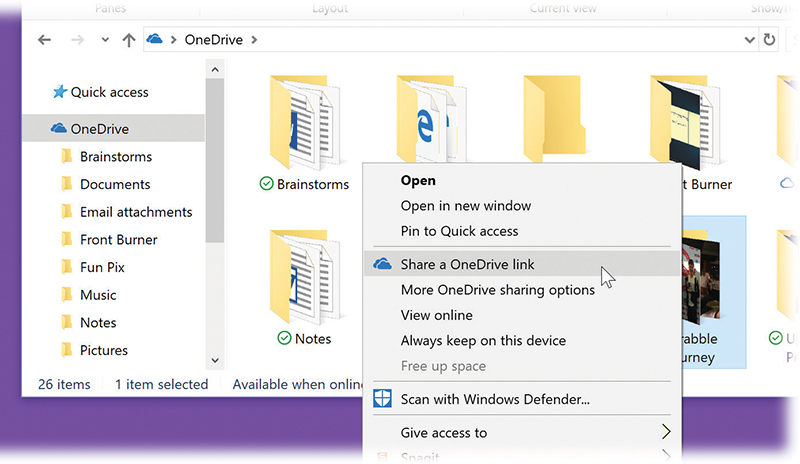

What Windows does index is everything in your personal folder: email, pictures, music, videos, program names, entries in your People and Calendar apps, Office documents, and so on. It searches your OneDrive, too (“OneDrive”), as well as your libraries (“Libraries”), even if they contain folders from other computers on your network.

Similarly, it searches offline files that belong to you, even though they’re stored somewhere else on the network.

Note:

Windows indexes all the drives connected to your PC, but not other hard drives on the network. You can, if you wish, add other folders to the list of indexed locations manually (“Adding New Places to the Index”).

Windows does index the personal folders of everyone else with an account on your machine (Chapter 18), but you’re not allowed to search them. So if you were hoping to search your spouse’s email for phrases like “Meet you at midnight,” forget it.

Adding New Places to the Index

On the other hand, suppose there’s some folder on another disk (or elsewhere on the network) that you really do want to be able to search the good way—contents and all, nice and fast. You can do that by adding it to your PC’s search index.

And you can do that in a couple of ways:

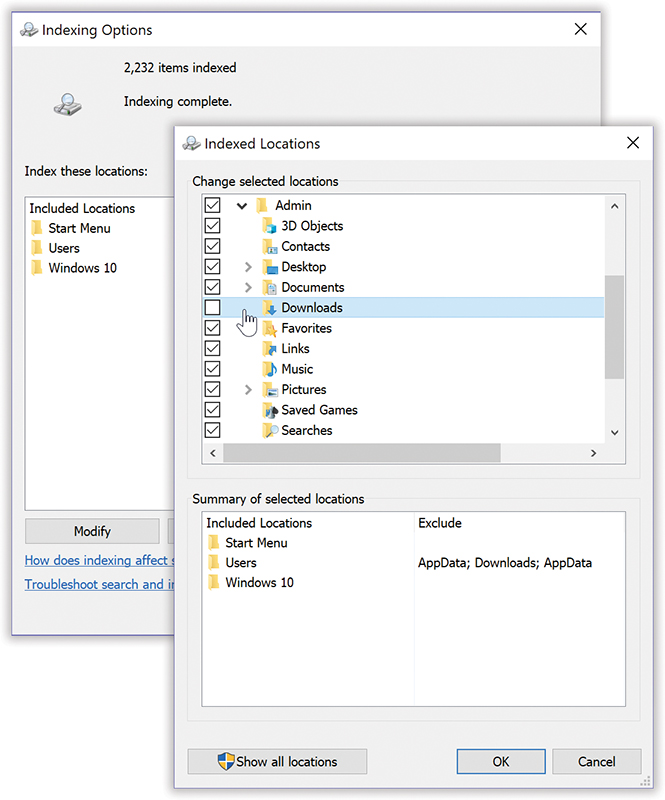

Add it from the Filters menu. After running a search, open the Filters menu (Figure 3-2), scroll all the way down to “Change where Windows searches,” and hit “Select locations.” The Indexing Options dialog box appears; see Figure 3-3.

You can remove folders from the index, too, maybe because you have privacy concerns (for example, you don’t want your coworkers searching your stuff while you’re away from your desk). Or maybe you just want to create more focused searches, removing a lot of old, extraneous junk from Windows’ database.

Tip:

If you’re trying to get some work done while Windows is in the middle of building the index, and the indexing is giving your PC all the speed of a slug in winter, you can click the Pause button. Windows will cool its jets for 15 minutes before it starts indexing again.

Add it to a library. Drag any folder into one of your libraries (“Libraries”). After a couple of minutes of indexing, that folder is now ready for insta-searching, contents and all, just as though it were born on your own PC.

This dialog box offers a few other useful search settings; see “Indexing Options”.

Figure 3-3. In the Indexing Options box, you can add or remove disks, partitions, or folders, thereby editing the list of searchable items.

Start by opening Indexing Options (left), and then click Modify. Now expand the flippy triangles, if necessary, to see the list of folders on your hard drive. Turn a folder’s checkbox on (to have Windows index it) or off (to remove it from the index, and therefore from searches). In this example, you’ve just told Windows to stop indexing your Downloads folder. Click OK.

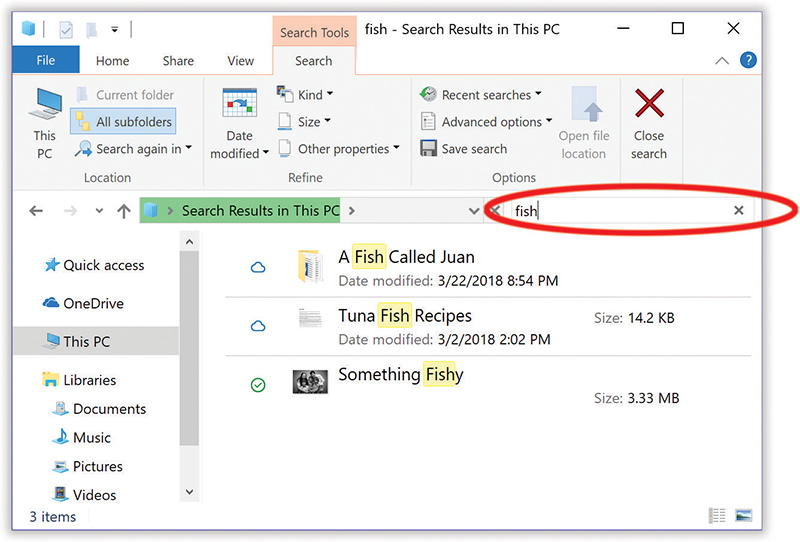

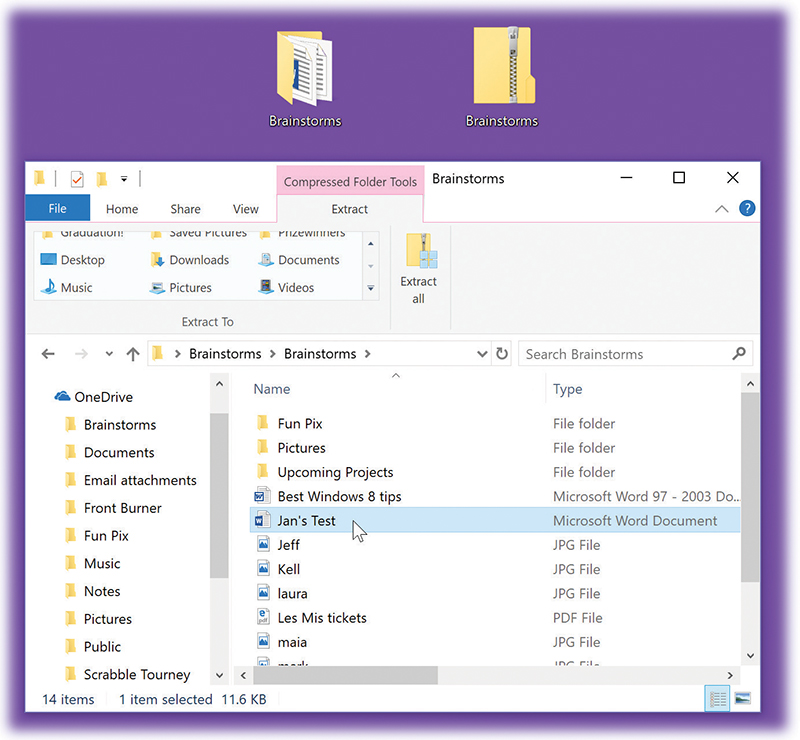

File Explorer Window Searches

See the search box at the top right of every File Explorer window (Figure 3-4)? This, too, is a piece of the Search empire. But there’s a big difference: The Cortana search box searches your entire computer. The search box in a File Explorer window searches only that window (and folders within it).

As you type, the window changes to show search results (in Content view).

The beauty of an Explorer window search is that it’s not limited to the height of the Cortana menu. Even if there are a lot of results, you see them all in one massively scrolling window.

Once the results appear, you can change the window view if that’s helpful—or sort, filter, and group them, just as you would in any other Explorer window.

And now, three glorious tips about starting Explorer-window searches:

You can make the search box bigger—by dragging the divider bar (between the address bar and the search box) to the left. Useful when you’re searching for your novel in progress: “The Sudden Disappearance, Reappearance, and then Disappearance Again of Sean O’Flanagan at the Dawn of the Elizabethan Era.”

Ordinarily, when you just start typing in a File Explorer window, you highlight the first icon whose name matches your typing. But in the Folder Options dialog box (“The “Folder Options” Options”), on the View tab, if you scroll down about three miles, you’ll find an option called “When typing into list view.” Turn on “Automatically type into the Search Box.” Now you save yourself a click every time you search; the mere act of typing initiates a search. (Despite the wording of this option, it works in any icon view—not just list view.)

Figure 3-4. The instant you click into the search box (circled), the Search tab of the Ribbon mysteriously appears. Marvel at the wealth of searching opportunity facing you.

Search Options on the Ribbon

When you use the File Explorer search box, the Ribbon magically sprouts a new tab, called Search (Figure 3-4). It’s teeming with options, including search filters that help you weed down a big list of results:

This PC. This button, at far left, does the opposite of weed down your results—it expands the scope of your search. You’ve just searched this Explorer window, but this button applies the same search to your entire computer.

Current folder. An Explorer search usually searches the window that’s open and all the folders inside it. If you click this button, though, you eliminate the subfolders from the results.

All subfolders. Remember the fun you had reading the “Current folder” paragraph just now? This button has the opposite function. It expands the search’s reach to include this window’s subfolders once again.

Search again in. This handy drop-down menu lists places you’ve recently searched. Now and then, one of these options can save you time and fiddling.

Date modified, Kind, Size, Other properties. These are search filters. They refine your search, letting you limit the results to certain date ranges, file types, file sizes, and so on.

When you use these menus, you’ll see codes in blue text appear in the search box—for example, datemodified:last week or size:medium. If you’re more of a keyboard person than a mouse person, you could type those codes into the search box yourself; the result is exactly the same, as described in the next section. In other words, the options on the Ribbon are nothing more than user-friendlified, quicker ways of entering the same search codes.

Tip:

You can adjust the second part of each code just by clicking it. For example, if you chose size:small and you really wanted size:medium—or if the size:small query didn’t produce any results—then click the word small. The pop-up menu of sizes appears again so you can adjust your selection.

You can use as many of these filters as you want. The more you click them (or type the corresponding shorthand), the longer the codes are in the search box. If you want to find medium files created by Casey last year with the tag Murgatroid project, go right ahead.

So what do they do? The “Date modified” drop-down menu offers choices like Today, Yesterday, Last Month, and This Year. “Kind” is a long list of file types, with choices like Folder, Game, Note, Picture, and Web History. “Size” offers file-size ranges like Tiny (0 to 10 KB), Medium (100 KB to 1 MB), Huge (16 to 128 MB), and Gigantic (greater than 128 MB).

As for the miscellaneous filters in the “Other properties” pop-up menu—well, they require some explanation.

Type lets you specify (after the word Type: in the search box) what general kind of thing you’re looking for: picture, sound, PDF, document, folder, disk image, backup, JPG, DOC, and so on. More on types in a moment.

Name lets you search for something by its filename only. (Otherwise, Windows also shows you search results based on the words inside the files.)

Folder path lets you type out the folder path (“The File Explorer Address Bar”) of something you’re seeking.

Finally, Tags lets you search for items according to the label you’ve applied to them, as described in “Tags, Metadata, and Properties”.

Recent searches displays—correct!—recent searches you’ve performed. It uses the shorthand described above, like “portrait of mary kind:image” or “Book list size:medium.”

Advanced options is a shortcut to some of the options described in “Adding New Places to the Index”, pertaining to non-indexed locations (that is, other computers on your network, or external drives). Here you can turn on the searching of zipped files and system files in those places, or turn on searching of text inside their files. You also get a shortcut to the Indexing Options dialog box described in “File Explorer Window Searches”.

Save search. This button becomes available once you’ve set up a search.

When clicked, it generates a saved search file and asks you to name it. (Behind the scenes, it’s a special document with the filename extension .search-ms.) Windows proposes stashing it in your Saved Searches folder, inside your personal folder, but you can choose any location you like—including the desktop.

Whenever you click the saved search, you get an instantaneous update of the search you originally set up.

The idea is to save you time when you regularly have to set up the same search; for example, maybe every week you have to round up all the documents authored by you that pertain to the Higgins proposal and save them to a flash drive. A search folder can do the rounding-up part with a single click. These items’ real locations may be all over the map, scattered in folders throughout your PC. But through the magic of the saved search, they appear as though they’re all in one neat window.

Note:

Unfortunately, there’s no easy way to edit a search folder. If you decide your original search criteria need a little fine-tuning, the simplest procedure is to set up a new search—correctly this time—and save it with the same name as the first one; accept Windows’ offer to replace the old one with the new.

Incidentally: Search filters work by hiding all the icons that don’t match. So don’t be alarmed if you click Size and then Small—and most of the files in your window suddenly disappear. Windows is doing what it thinks you wanted—showing you only the small files—in real time, as you adjust the filters.

At any time, you can bring all the files back into view by clicking the ![]() at the right end of the search box.

at the right end of the search box.

Limit by Size, Date, Rating, Tag, Author…

Suppose you’re looking for a file called Big Deals.doc. But when you type big into the search box, you wind up wading through hundreds of files that contain the word “big.”

It’s at times like these you’ll be grateful for Windows’ little-known criterion searches. These are syntax tricks that help you create narrower, more targeted searches. All you have to do is prefix your search query with the criterion you want, followed by a colon.

An example is worth a thousand words, so several examples should save an awful lot of paper. You can type these codes into the search box in an Explorer window (they don’t work in the main search box):

name: big finds only documents with “big” in their names. Windows ignores anything with that term inside the file.

tag: crisis finds only icons with “crisis” as a tag—not as part of the title or contents.

created: 7/25/18 finds everything you wrote on July 25, 2018. You can also use modified: today or modified: yesterday, for that matter. Or don’t be that specific. Just use modified: July or modified: 2018.

You can use symbols like < and >, too. To find files created since yesterday, you could type created: >yesterday.

Or use two dots to indicate a range. To find all the email you got in the first two weeks of March 2018, you could type received: 3/1/2018..3/15/2018. (That two-dot business also works to specify a range of file sizes, as in size: 2 MB..5 MB.)

Tip:

That’s right: Windows recognizes human terms like today, yesterday, this week, last week, last month, this month, and last year.

size: >2gb finds all the big files on your PC.

rating: <*** finds documents to which you’ve given ratings of three stars or fewer.

camera model: Sony A7 finds all the pictures you took with that camera.

kind: email finds all the email messages.

That’s just one example of the power of kind. Here are some other kinds you can look for: calendar, appointment, or meeting (appointments in Outlook, iCal, or vCalendar files); communication (email and attachments); contact or person (vCard and Windows Contact files, Outlook contacts); doc or document (text, Office, PDF, and web files); folder (folders, .zip files, .cab files); link (shortcut files); music or song (audio files, Windows Media playlists); pic or picture (graphics files like JPEG, PNG, GIF, and BMP); program (programs); tv (shows recorded by Windows Media Center); and video (movie files).

The folder: prefix limits the search to a certain folder or library. (The starter words under:, in:, and path: work the same way.) So folder: music confines the search to your Music library, and a search for in: documents turtle finds all files in your Documents library containing the word “turtle.”

Tip:

You can combine multiple criteria searches, too. For example, if you’re pretty sure you had a document called “Naked Mole-Rats” that you worked on yesterday, you could cut directly to it by typing mole modified: yesterday or modified: yesterday mole. (The order doesn’t matter.)

So where’s the master list of these available criteria? It turns out they correspond to the column headings at the top of an Explorer window in Details view: Name, Date modified, Type, Size, and so on.

You’re not limited to just the terms you see now; you can use any term that can be an Explorer-window heading. To see them all, right-click any of the existing column headings in a window that’s set to Details view. From the shortcut menu, choose More. There they are: 115 different criteria, including Size, Rating, Album, Bit rate, Camera model, Date archived, Language, Nickname, and so on. Here’s where you learn that, for example, to find all your Ohio address-book friends, you’d search for home state or province: OH.

Dude, if you can’t find what you’re looking for using all those controls, it probably doesn’t exist.

Special Search Codes

Certain shortcuts in the File Explorer search boxes can give your queries more power. For example:

Document types. You can type document to find all text, spreadsheet, and PowerPoint files. You can also type a filename extension—.mp3 or .doc or .jpg, for example—to round up all files of a certain file type.

Tags, authors. This is payoff time for applying tags or author names to your files (“Tags, Metadata, and Properties”). In a search box, you can type, or start to type, Gruber Project (or any other tag you’ve assigned), and you get an instantaneous list of everything that’s relevant to that tag. Or you can type Mom or Casey or any other author’s name to see all the documents that person created.

Utility apps. Windows comes with a bunch of geekhead programs that aren’t listed in the Start menu and have no icons—advanced technical tools like RegEdit (the Registry Editor), Command Prompt (the command line), and so on. By far the quickest way to open them is to type their names into the search box.

In this case, however, you must type the entire name—regedit, not just rege. And you have to use the program’s actual, on-disk name (regedit), not its human name (Registry Editor).

Quotes. If you type in more than one word, Search works just the way Google does. That is, it finds things that contain both words somewhere inside.

If you’re searching for a phrase where the words really belong together, though, put quotes around them. For example, searching for military intelligence rounds up documents that contain those two words, but not necessarily side by side. Searching for “military intelligence” finds documents that contain that exact phrase. (Insert your own political joke here.)

Boolean searches. Windows also permits combination-search terms like AND and OR, better known to geeks as Boolean searches.

That is, you can round up a single list of files that match two terms by typing, say, vacation AND kids. (That’s also how you’d find documents coauthored by two specific people—you and a pal, for example.)

Note:

You can use parentheses instead of AND, if you like. That is, typing (vacation kids) finds documents that contain both words, not necessarily together.

If you use OR, you can find icons that match either of two search criteria. Typing jpeg OR mp3 will turn up photos and music files in a single list.

The word NOT works, too. If you did a search for dolphins, hoping to turn up sea-mammal documents, but instead find your results contaminated by football-team listings, then by all means repeat the search with dolphins NOT Miami. Windows will eliminate all documents containing “Miami.”

Note:

You must type Boolean terms like AND, OR, and NOT in all capitals.

You can even combine Boolean terms with the other special search terms described in this chapter. Find everything created in the past couple of months by searching for created: September OR October, for example. If you’ve been entering your name into the Properties dialog box of Microsoft Office documents, you can find all the ones created by Casey and Robin working together using author:(Casey AND Robin).

Customizing Search

You’ve just read about how Search works fresh out of the box. But you can tailor its behavior, either for security reasons or to customize it to the kinds of work you do.

Unfortunately for you, Microsoft has stashed the various controls that govern searching into three different places. Here they are, one area at a time.

Cortana Settings

In ![]() →

→![]() →Cortana, you’ll find some settings that govern how your PC conducts web searches. For example, you can apply some sex-and-hate filtering to its search results, make it stop keeping a record of your web searches, and so on. See “Setting Up Cortana”.

→Cortana, you’ll find some settings that govern how your PC conducts web searches. For example, you can apply some sex-and-hate filtering to its search results, make it stop keeping a record of your web searches, and so on. See “Setting Up Cortana”.

Note:

As you may have discovered, the main search box produces results both from your computer and from the web, in a single list. If you squint your eyes a little and really think about it, that arrangement doesn’t make much sense. You wouldn’t search your hard drive to place an order from Amazon.com, and you wouldn’t search the web for that spreadsheet you worked on in December.

Unfortunately, Windows 10 no longer offers a switch that eliminates web results from searches. If you’re technically proficient, however, you can pull off that stunt using the Group Policy Editor or a registry edit; see the free PDF supplement to this chapter, “Making Cortana Omit Web Results from Searches.” You can download it from this book’s “Missing CD” page at www.missingmanuals.com.

Folder Options

The second source of search settings is the Folder Options→Search dialog box. To open it, find the View tab on the Ribbon in any Explorer window; click Options. In the resulting dialog box, click the Search tab. Here’s what you’ll find:

Don’t use the index when searching in file folders for system files. If you turn this item on, Windows won’t use its internal Dewey Decimal System for searching Windows itself. It will, instead, perform the names-only, slower type of search.

So who on earth would want this turned on? You, if you’re a programmer or system administrator and you’re worried that the indexed version of the system files might be out of date. (That happens, since system files change often, and the index may take some time to catch up.)

Include system directories. When you’re searching a disk that hasn’t been indexed, do you want Windows to look inside the folders that contain Windows itself (as opposed to just the documents people have created)? If yes, then turn this on.

Include compressed files (ZIP, CAB…). When you’re searching a disk that hasn’t been indexed, do you want Windows to search for files inside compressed archives, like .zip and .cab files? If yes, then turn on this checkbox. (Windows doesn’t ordinarily search archives, even on an indexed hard drive.)

Always search file names and contents. As the previous pages make clear, the Windows search mechanism relies on an index—an invisible database that tracks the location, contents, and metadata of every file. If you attach a new hard drive, or attempt to search another computer on the network that hasn’t been indexed, then Windows ordinarily just searches its files’ names. After all, it has no index to search for that drive.

If Windows did attempt to index those other drives, you’d sometimes have to wait awhile, at least the first time, because index-building isn’t instantaneous. That’s why the factory setting here is Off.

But if you really want Windows to search the text inside the other drives’ files, even without an index—which can be painfully slow—then turn this checkbox on instead.

Indexing Options

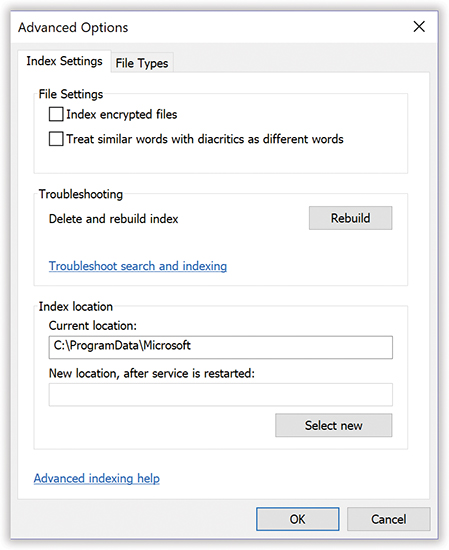

The third location of search settings is shown in Figure 3-5. This is Index Settings, the master control over the search index, the massive, invisible, constantly updated database file that tracks your PC’s files and what’s in them. As described earlier, you can use this dialog box to add or remove folders from what Windows is tracking.

But there are a few more handy options here, lurking behind the Advanced Indexing Options button.

To open this box, click in the Cortana search box, type a random letter or two, and, in the results list, hit Filters. Scroll way down until you can see and choose “Select locations.”

Figure 3-5. Search works beautifully right out of the box. For the benefit of the world’s tweakers, however, this dialog box awaits, filled with technical adjustments to the way Search works.

By clicking Modify, you can add or remove folders and disks from Windows’ searchlight (Figure 3-5).

Index Settings tab

But if you click Advanced instead, and authenticate if necessary, you’re ready to perform some powerful additional tweaks. On the first tab (Figure 3-5), here’s the kind of fun you can have:

Index encrypted files. Windows can encrypt files and folders with a quick click, making them unreadable to anyone who receives one by email, say, and doesn’t have the password. This checkbox lets Windows index these files (the ones you’ve encrypted, of course; this isn’t a back door to files you can’t otherwise access).

Treat similar words with diacritics as different words. The word “ole,” as might appear cutely in a phrase like “the ole swimming pool,” is quite a bit different from “olé,” as in, “You missed the matador, you big fat bull!” The difference is a diacritical mark (øne öf mâny littlé lañguage märks).

Ordinarily, Windows ignores diacritical marks; it treats “ole” and “olé” as the same word in searches. That’s designed to make it easier for the average person who can’t remember how to type a certain marking, or which direction the mark goes. But if you turn on this box, Windows will observe these markings and treat marked and unmarked words differently.

Troubleshooting. If the Search command ever seems to be acting wacky—for example, it’s not finding a document you know is on your computer—Microsoft is there to help you.

Your first step should be to click “Troubleshoot search and indexing.” (It appears both here, on the Advanced panel, and on the main Indexing Options panel.) The resulting step-by-step sequence may fix things.

If it doesn’t, click Rebuild. Now Windows wipes out the index it’s been working with, completely deleting it—and then begins to rebuild it. You’re shown a list of the disks and folders Windows has been instructed to index; the message at the top of the dialog box lets you know its progress. With luck, this will wipe out any funkiness you’ve been experiencing.

Move the index. Ordinarily, Windows stores its invisible index file on your main hard drive. But you might have good reason for wanting to move it. Maybe your main drive is getting full. Or maybe you’ve bought a second, faster hard drive; if you store your index there, searching will be even faster.

In the Advanced Options dialog box, click “Select new.” Navigate to the disk or folder where you want the index to go, and then click OK. (The actual transfer of the file takes place the next time you start up Windows.)

File Types tab

Windows ordinarily searches for just about every kind of useful file: audio files, program files, text and graphics files, and so on. It doesn’t bother peering inside things like Windows operating system files and applications, because what’s inside them is programming code with little relevance to most people’s work. Omitting these files from the index keeps the index smaller and the searches fast.

But what if you routinely traffic in very rare Venezuelan Beekeeping Interchange Format (VBIF) documents—a file type your copy of Windows has never met before? You won’t be able to search their contents unless you specifically teach Windows about them.

In the Advanced Options dialog box, click the File Types tab. Type the filename extension (like VBIF) into the text box at the lower left. Click Add and then OK. From now on, Windows will index this new file type.

On the other hand, if you find that Windows uses up valuable search-results menu space listing, say, web bookmarks—stuff you don’t need to find very often—you can tell it not to bother. Now the results list won’t fill up with files you don’t care about.

Turn the checkboxes on or off to make Windows start or stop indexing them.

Using the “How should this file be indexed” options at the bottom of the box, you can also make Windows stop searching these files’ contents—the text within them—for better speed and a smaller index.

The Folders of Windows 10

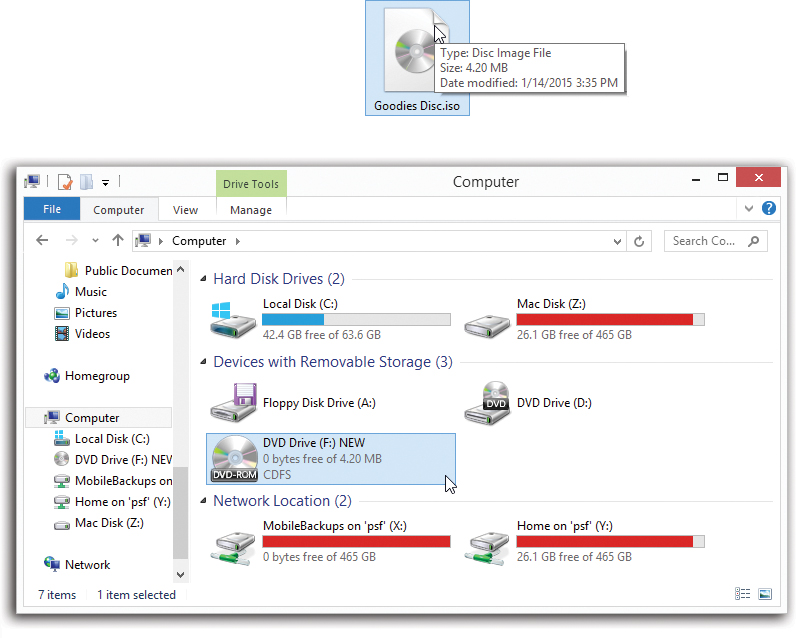

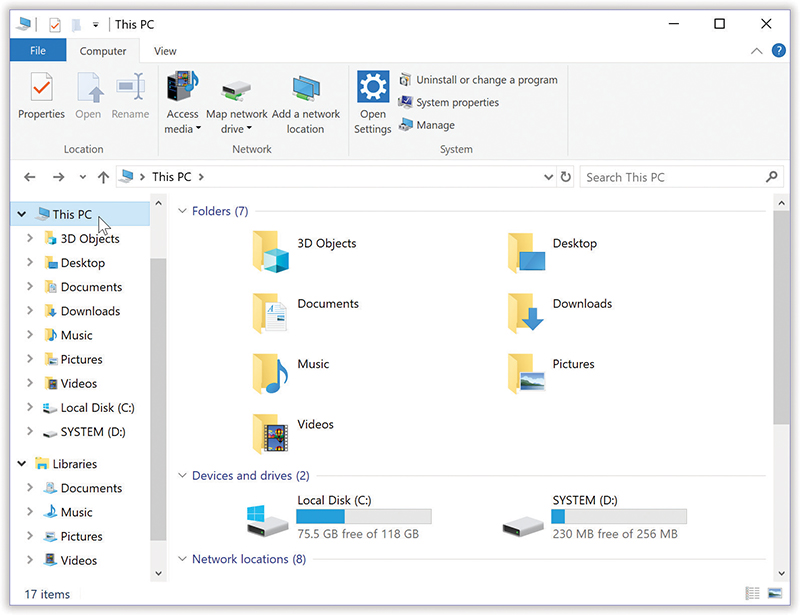

The top-level, all-encompassing, mother-ship window of your PC is the This PC window (formerly called Computer, formerly formerly called My Computer). From within this window, you have access to every disk, folder, and file on your computer. Its slogan might well be “If it’s not in here, it’s not on your PC.”

To see it, open an Explorer window and click This PC in the navigation pane.

You wind up face to face with the icons of every storage gizmo connected to your PC: hard drives, CD and DVD drives, USB flash drives, digital cameras, and so on (Figure 3-6).

Tip:

Ordinarily, every drive has an icon in here, even if no disk or memory card is in it. That can be annoying if your laptop has, for example, four memory-card slots, each for a different kind of card, labeled D:, E:, F:, and G:, and your This PC window is getting a little hard to navigate.

Fortunately, Windows can hide your drive icons when they’re empty. To turn that on or off, open Folder Options (click Options on the Ribbon’s View tab). Click the View tab. Click “Hide empty drives,” and then click OK.

Now your removable-disk/card drives appear only when something is in them—a CD, a DVD, or a memory card, for example.

Most people, most of the time, are most concerned with the Local Disk (C:), which represents the internal hard drive preinstalled in your computer. (You’re welcome to rename this icon, by the way, just as you would any icon.)

Note:

The drive lettering, such as C: for your main hard drive, is an ancient convention that doesn’t offer much relevance these days. (Back at the dawn of computing, the A: and B: drives were floppy drives.)

Since Windows now displays icons and plain-English names for your drives, you might consider the drive-letter display to be a bit old-fashioned and cluttery. Fortunately, you can hide it (“View Tab”).

Figure 3-6. The This PC window is the starting point for any and all folder-digging. It shows the “top-level” folders: the disk drives of your PC. If you double-click the icon of a removable-disk drive (such as your CD or DVD drive), you receive only a “Please insert a disk” message, unless there’s actually a disk in the drive.

What’s in the Local Disk (C:) Window

If you double-click the Local Disk (C:) icon in This PC—that is, your primary hard drive—you’ll find, at least, these standard folders.

Intel (or AMD)

This folder contains drivers (Chapter 14) for your PC’s circuit board, or log (record-keeping) files about your computer’s doings, for use by a technician in times of troubleshooting.

PerfLogs

Windows Reliability and Performance Monitor is one of Windows’ hidden maintenance apps that knowledgeable tech s can use to measure your PC’s health and speed. This folder is where it dumps its logs, or reports.

Program Files

This folder contains all your desktop programs—Word, Excel, games, and so on.

Of course, a Windows program isn’t a single, self-contained icon. Instead, it’s usually a folder, housing both the program and its phalanx of support files and folders. The actual application icon generally can’t even run if it’s separated from its support group.

Program Files (x86)

If you’ve installed a 64-bit version of Windows, this folder is where Windows puts all your older 32-bit programs.

Users

Windows’ accounts feature is ideal for situations where different family members, students, or workers use the same machine at different times. Each account holder will turn on the machine to find her own separate, secure set of files, folders, desktop pictures, web bookmarks, font collections, and preference settings. (Much more about this feature in Chapter 18.)

In any case, now you should see the importance of the Users folder. Inside is one folder—one personal folder—for each person who has an account on this PC. In general, Standard account–holders (“Standard accounts”) aren’t allowed to open anybody else’s folder.

Note:

Inside the Documents library, you’ll see Public Documents; in the Music library, you’ll see Public Music; and so on. These are nothing more than pointers to the master Public folder that you can also see here, in the Users folder. (Anything you put into a Public folder is available for inspection by anyone else with an account on your PC, or even other people on your network.)

Windows

Here’s a folder Microsoft hopes you’ll just ignore. This most hallowed folder contains the thousands of little files that make Windows, well, Windows. Most of these folders and files have cryptic names that appeal to cryptic people.

In general, the healthiest PC is one whose Windows folder has been left alone.

Windows10Upgrade

This folder contains the Windows 10 Update Assistant app, which you encounter when upgrading your PC to a newer version of Windows 10. You can safely delete it (using the “Apps & features” screen, “Apps”).

Your Personal Folder

Everything that makes your Windows experience your own sits inside the Local Disk (C:) ![]() Users

Users ![]() [your name] folder. This is your personal folder, where Windows stores your preferences, documents, email, pictures, music, web favorites, cookies (described in “Five Degrees of Web Protection”), and so on.

[your name] folder. This is your personal folder, where Windows stores your preferences, documents, email, pictures, music, web favorites, cookies (described in “Five Degrees of Web Protection”), and so on.

Tip:

Actually, it would make a lot of sense for you to install your personal folder’s icon in the “Quick access” list at the left side of every Explorer window. Drag its icon directly into the list.

To create a new folder, right-click where you want the folder to appear (on the desktop or in any File Explorer window except This PC), and choose New→Folder from the shortcut menu. The new folder appears with its temporary “New Folder” name highlighted. Type a new name for the folder and then press Enter.

But your personal folder also comes prestocked with folders like these:

3D Objects. This folder contains any 3D models you build using Windows 10’s creative apps, like Paint 3D and Mixed Reality Viewer. (You can’t delete this folder manually. That job requires a Registry hack; you can find instructions for it using Google.)

Contacts. An address-book program called Windows Contacts came with Windows Vista, but Microsoft gave it a pink slip for Windows 7. All that’s left now is this folder, where it used to stash the information about your social circle. (Some other companies’ address-book programs can use this folder, too.)

Desktop. When you drag an icon out of a folder or disk window and onto your desktop, it may appear to show up on the desktop. But that’s just a visual convenience. In truth, nothing in Windows is ever really on the desktop; it’s just in this Desktop folder, and mirrored on the desktop.

Everyone who shares your machine, upon signing in, sees his own stuff sitting out on the desktop. Now you know how Windows does it; there’s a separate Desktop folder in every person’s personal folder. (You can entertain yourself for minutes trying to prove this. If you drag something out of your Desktop folder, it also disappears from the actual desktop. And vice versa.)

Note:

A link to this folder appears in the navigation pane of every Explorer window.

Downloads. When you download anything from the web, your browser suggests storing it on your computer in this Downloads folder. The idea is to save you the frustration of downloading stuff and then not being able to find it later.

Favorites. This folder stores shortcuts of the files, folders, and other items you’ve designated as favorites (that is, web bookmarks). This can be handy if you want to delete a bunch of your favorites all at once, rename them, or whatever.

Links. In older Windows versions, this folder’s icons corresponded to the easy-access links in the Favorite Links list in your Explorer windows. Today, it’s a random collection of icon shortcuts used by various other Windows features (like saved searches).

Documents. Microsoft suggests you keep your actual work files in this folder. Sure enough, whenever you save a new document (when you’re working in Word or Photoshop Elements, for example), the Save As box proposes storing the new file in this folder.

Tip:

You can move the Documents folder, if you like. For example, you can move it to a removable drive, like a pocket hard drive or a USB flash drive, so you can take it back and forth to work with you and always have your latest files at hand.

To do so, open your Documents folder. Right-click a blank spot in the window; from the shortcut menu, choose Properties. Click the Location tab, click Move, navigate to the new location, and click Select Folder.

What’s cool is that the Documents link in every Explorer window’s navigation pane still opens your Documents folder. What’s more, your programs still propose storing new documents there—even though the folder isn’t where Microsoft originally put it.

Music, Pictures, Videos. You guessed it: These are Microsoft’s proposed homes for your multimedia files. These are where song files from ripped CDs, photos from digital cameras, and videos from camcorders go.

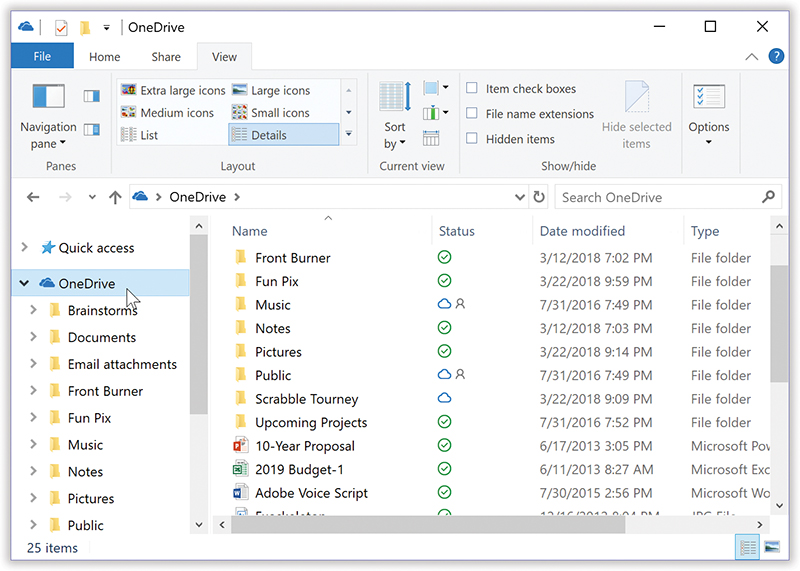

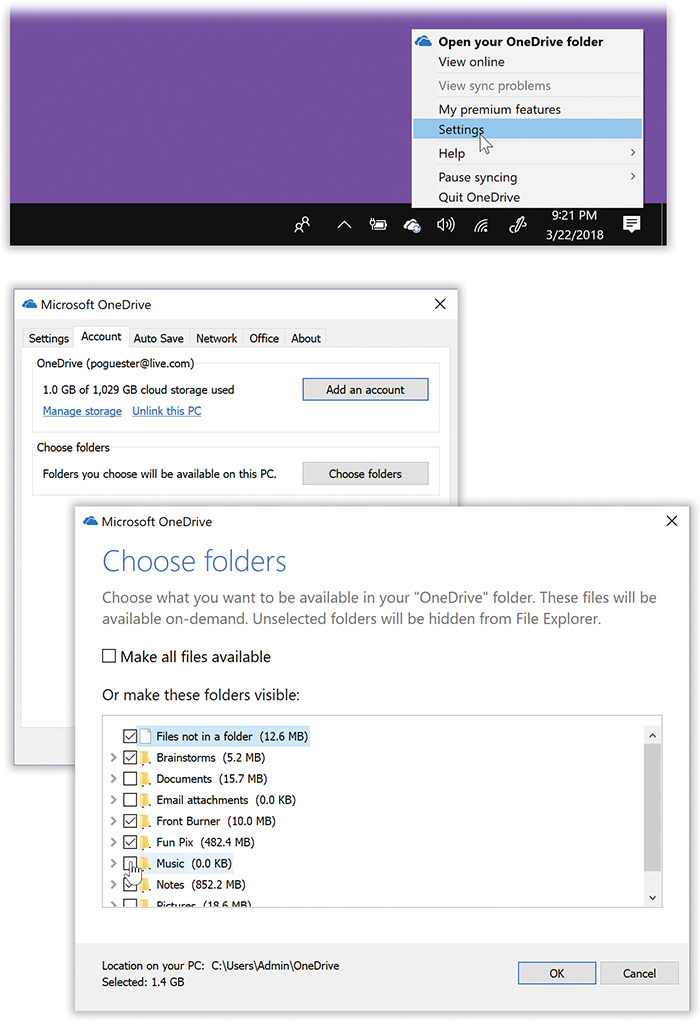

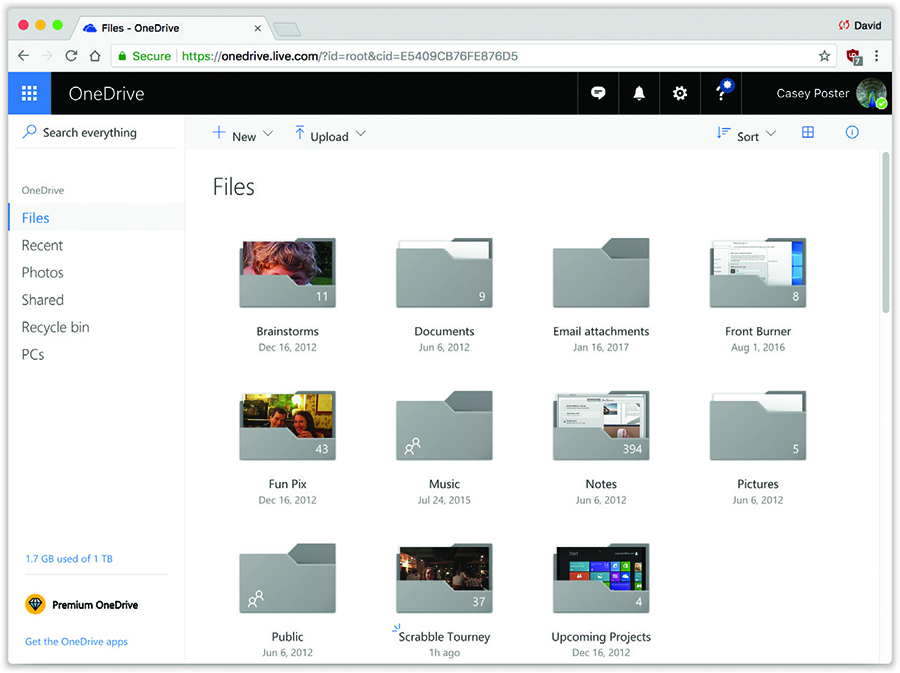

OneDrive. This is the actual, for-real storage location for your machine’s local copy of the files and folders on your OneDrive (“OneDrive”).

Saved Games. When you save a computer game that’s in progress, the game should propose storing it here, so you can find it again later. (It may take some time before all the world’s games are updated to know about this folder.)

Searches. As described in “Limit by Size, Date, Rating, Tag, Author…”, you can save searches for reuse later. This folder stores shortcuts for them.

Note:

Your personal folder also stores a few hidden items reserved for use by Windows itself. One of them is AppData, a very important folder that stores all kinds of support files for your programs. For example, it stores word-processor dictionaries, web cookies, your Media Center recordings, Edge security certificates, and so on. In general, there’s not much reason for you to poke around in them, but in this book, here and there, you’ll find tips and tricks that refer you to AppData.

Selecting Icons

Before you can delete, rename, move, copy, or otherwise tamper with any icon, you have to be able to select it somehow. By highlighting it, you’re essentially telling Windows what you want to operate on.

By Tapping or Clicking

To select one icon, just click it once. To select multiple icons at once—in preparation for moving, copying, renaming, or deleting them en masse, for example—use one of these techniques:

Select all. Highlight all the icons in a window by using the “Select all” button on the Ribbon’s Home tab. (Or press Ctrl+A, its keyboard equivalent.)

Highlight several consecutive icons. Start with your cursor above and to one side of the icons, and then drag diagonally. As you drag, you create a temporary shaded blue rectangle. Any icon that falls within this rectangle darkens to indicate that it’s been selected.

Alternatively, click the first icon you want to highlight, and then Shift-click the last one. All the files in between are automatically selected, along with the two you clicked. (These techniques work in any folder view: Details, Icon, Content, or whatever.)

Tip:

If you include a particular icon in your diagonally dragged group by mistake, Ctrl-click it to remove it from the selected cluster.

Highlight nonconsecutive icons. Suppose you want to highlight only the first, third, and seventh icons in the list. Start by clicking icon No. 1; then Ctrl-click each of the others. (If you Ctrl-click a selected icon again, you deselect it. A good time to use this trick is when you highlight an icon by accident.)

Tip:

The Ctrl key trick is especially handy if you want to select almost all the icons in a window. Press Ctrl+A to select everything in the folder, and then Ctrl-click any unwanted items to deselect them.

By Typing

You can also highlight one icon, plucking it out of a sea of pretenders, by typing the first few letters of its name. Type nak, for example, to select an icon called “Naked Chef Broadcast Schedule.”

Eliminating Double-Clicks

In some ways, a File Explorer window is just like a web browser. It has a Back button, an address bar, and so on.

If you enjoy this PC-as-browser effect, you can actually take it one step further. You can set up your PC so that one click, not two, opens an icon. It’s a strange effect that some people adore, that some find especially useful on touchscreens—and that others turn off as fast as their little fingers will let them.

In any File Explorer window, on the View tab of the Ribbon, click Options.

The Folder Options control panel opens. Turn on “Single-click to open an item (point to select).” Then indicate when you want your icon’s names turned into underlined links by selecting “Underline icon titles consistent with my browser” (all icons’ names appear as links) or “Underline icon titles only when I point at them.” Click OK. The deed is done.

Now, if a single click opens an icon, you’re entitled to wonder how you’re supposed to select an icon (which you’d normally do with a single click). Take your pick:

Point to it for about a half-second without clicking. To make multiple selections, press the Ctrl key as you point to additional icons. (And to drag an icon, just ignore all this pointing stuff—simply drag as usual.)

Turn on the checkbox mode described next.

Checkbox Selection

It’s great that you can select icons by holding down a key and clicking—if you can remember which key must be pressed.

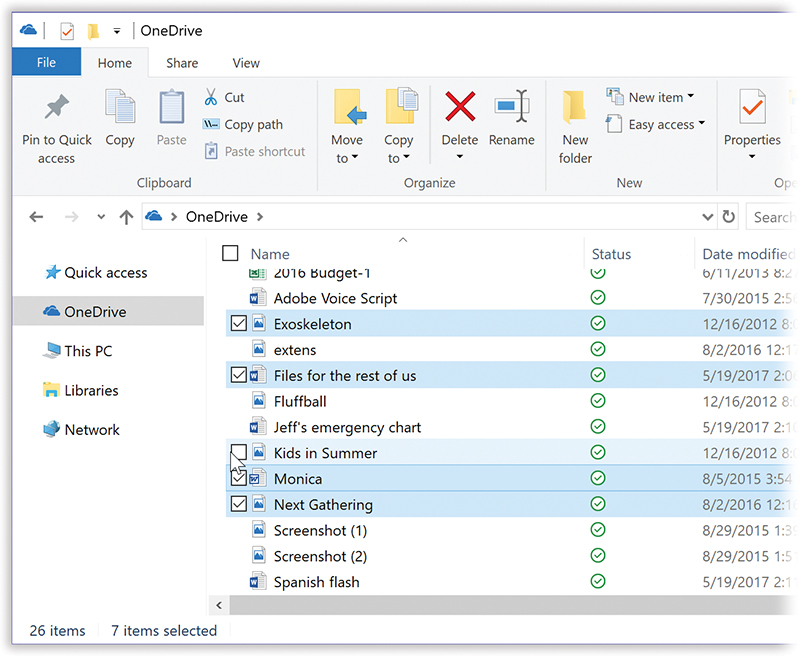

Turns out novices were befuddled by the requirement to Ctrl-click icons when they wanted to choose more than one. So Microsoft created a checkbox mode. In this mode, any icon you point to temporarily sprouts a little checkbox that you can click to select it (Figure 3-7).

To turn this feature on, open any Explorer window, and then turn on “Item check boxes,” which is on the View tab of the Ribbon.

Now, anytime you point to an icon, an on/off checkbox appears. No secret keystrokes are necessary for selecting icons; it’s painfully obvious how you’re supposed to choose only a few icons out of a gaggle.

Figure 3-7. Each time you point to an icon, a clickable checkbox appears. Once you turn it on, the checkbox remains visible, making it easy to select several icons at once. What’s cool about the checkboxes feature is that it doesn’t preclude your using the old click-to-select method; if you click an icon’s name, you deselect all checkboxes except that one.

Life with Icons

File Explorer has one purpose in life: to help you manage the icons of your files, folders, and disks. You could spend your entire workday just mastering the techniques of naming, copying, moving, and deleting these icons.

Here’s the crash course.

Renaming Your Icons

To rename a file, folder, printer, or disk icon, you need to open its “renaming rectangle.” You can do so with any of the following methods:

Highlight the icon and then press the F2 key.

Highlight the icon. On the Home tab of the Ribbon, click Rename.

Click carefully, just once, on a previously highlighted icon’s name.

Right-click the icon (or hold your finger down on it) and choose Rename from the shortcut menu.

Tip:

You can even rename your hard drive so you don’t go your entire career with a drive named “Local Disk.” Just rename its icon (in the This PC window) as you would any other.

In any case, once the renaming rectangle has appeared, type the new name you want and then press Enter. Use all the standard text-editing tricks: Press Backspace to fix a typo, press the ![]() and

and ![]() keys to position the insertion point, and so on. When you’re finished editing the name, press Enter to make it stick. (If another icon in the folder has the same name, Windows beeps and makes you choose another name.)

keys to position the insertion point, and so on. When you’re finished editing the name, press Enter to make it stick. (If another icon in the folder has the same name, Windows beeps and makes you choose another name.)

Tip:

If you highlight a bunch of icons at once and then open the renaming rectangle for any one of them, you wind up renaming all of them. For example, if you’ve highlighted three folders called Cats, Dogs, and Fish, then renaming one of them to Animals changes the original set of names to Animals (1), Animals (2), and Animals (3).

If that’s not what you want, press Ctrl+Z (the keystroke for Undo) to restore all the original names.

A folder or filename can technically be up to 260 characters long. In practice, though, you won’t be able to produce filenames that long; that’s because that maximum must also include the file extension (the three-letter suffix that identifies the file type) and the file’s folder path (like (C:) ![]() Users

Users ![]() Casey

Casey ![]() Pictures).

Pictures).

Note, too, that because they’re reserved for behind-the-scenes use, Windows doesn’t let you use any of these symbols in a Windows filename: / : * ? “ < > |

You can give more than one file or folder the same name, as long as they’re not in the same folder.

Note:

Windows comes factory-set not to show you filename extensions. That’s why you sometimes might think you see two different files called, say, “Quarterly Sales,” both in the same folder.

The explanation is that one filename may end with .doc (a Word document), and the other may end with .xls (an Excel document). But because these suffixes are hidden, the files look like they have exactly the same name. To unhide filename extensions, turn on the “File name extensions” checkbox. It’s on the View tab of the Ribbon.

Icon Properties

Properties are a big deal in Windows. Properties are preference settings that you can change independently for every icon on your machine.

To view the properties for an icon, choose from these techniques:

Right-click the icon; choose Properties from the shortcut menu.

Highlight the icon in an Explorer window; click the Properties button. It’s the wee tiny icon at the upper-left corner of the window, in the Quick Access toolbar. Looks like a tiny page with a checkmark (

).

).Highlight the icon. On the Ribbon, on the Home tab, click Properties.

While pressing Alt, double-click the icon.

Highlight the icon; press Alt+Enter.

Tip:

You can also see some basic info about any icon (type, size, and so on) by pointing to it without clicking. A little info balloon pops up, saving you the trouble of opening the Properties box or even the Details pane.

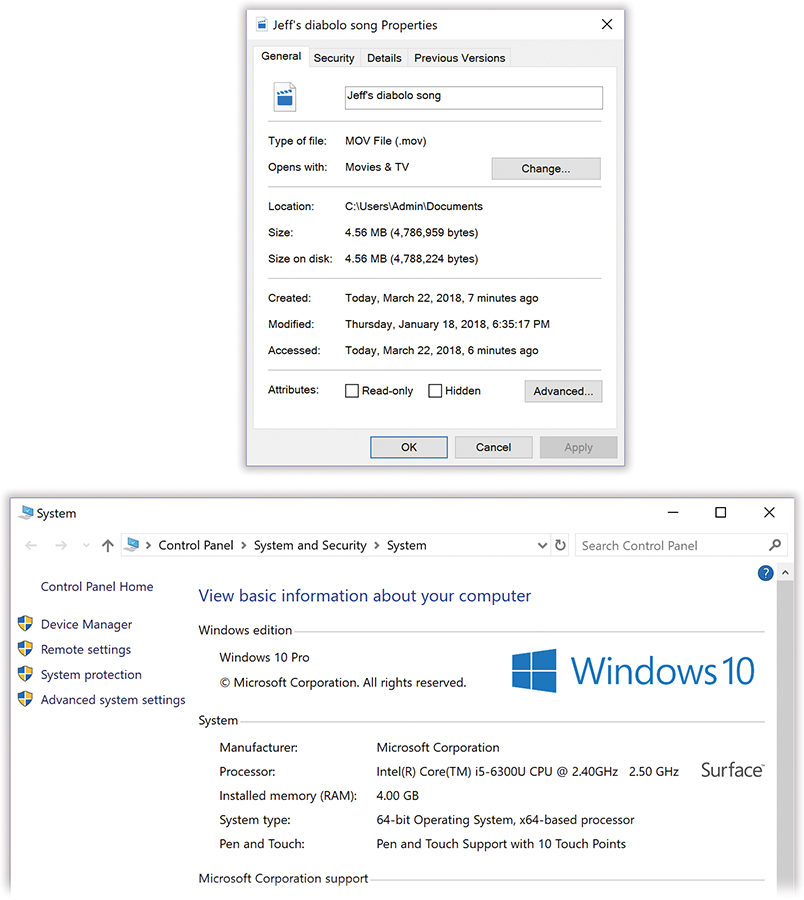

These settings aren’t the same for every kind of icon, however. Here’s what you can expect when opening the Properties dialog boxes of various icons (Figure 3-8).

This PC (System Properties)

There are about 500 different ways to open the Properties dialog box for your This PC icon. For example, you can click This PC in the navigation pane of any window and then click “System properties” on the Ribbon’s Computer tab. Or right-click the This PC icon (in the nav pane again); from the shortcut menu, choose Properties.

The System Properties window is packed with useful information about your machine: what kind of processor is inside, how much memory (RAM) it has, whether or not it has a touchscreen, and what version of Windows you’ve got.

The panel at the left side of the window (shown in Figure 3-8, bottom) includes some useful links—“Device Manager,” “Remote settings,” “System protection,” and “Advanced system settings”—all of which are described elsewhere in this book.

Note, however, that most of them work by opening the old System Properties Control Panel. Its tabs give a terse, but more complete, look at the tech specs and features of your PC. These, too, are described in the relevant parts of this book—all except “Computer Name.” Here you can type a plain-English name for your computer (“Casey’s Laptop,” for example). That’s how it will appear to other people on the network, if you have one.

Disks

In a disk’s Properties dialog box, you can see all kinds of information about the disk itself, like its name (which you can change right there in the box), its capacity (which you can’t), and how much of it is full.

This dialog box’s various tabs are also gateways to a host of maintenance and backup features, including Disk Cleanup, Error-Checking, Defrag, Backup, and Quotas; all of these are described in Chapter 17.

Figure 3-8. The Properties dialog boxes are different for every kind of icon. In the months and years to come, you may find many occasions when adjusting the behavior of some icon has big benefits in simplicity and productivity.

Top: The Properties dialog box for a song file.

Bottom: The Properties window for the computer itself looks quite a bit different. It is, in fact, part of the Control Panel.

Data files

The properties for a plain old document depend on what kind of document it is. You always see a General tab, but other tabs may also appear (especially for Microsoft Office files):

General. This screen offers all the obvious information about the document—location, size, modification date, and so on. The Read-only checkbox locks the document. In the read-only state, you can open the document and read it, but you can’t make any changes to it.

Note:

If you make a folder read-only, it affects only the files already inside. If you add additional files later, they remain editable.

Hidden turns the icon invisible. It’s a great way to prevent something from being deleted, but because the icon becomes invisible, you may find it a bit difficult to open yourself.

The Advanced button offers a few additional options. “File is ready for archiving” means “Back me up.” This message is intended for the old Backup and Restore program described in Chapter 16, and it indicates that this document has been changed since the last time it was backed up (or that it’s never been backed up). “Allow this file to have contents indexed in addition to file properties” lets you indicate that this file should, or should not, be part of the search index described earlier in this chapter.

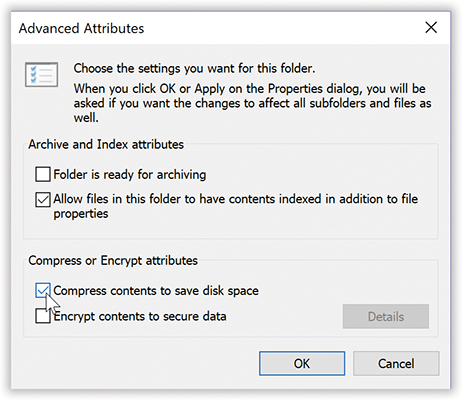

“Compress contents to save disk space” is described in “Compressing Files and Folders”. Finally, “Encrypt contents to secure data” is described in “Storage Spaces”.

Security has to do with the NTFS permissions of a file or folder, technical on/off switches that govern who can do what to the contents. You see this tab only if the hard drive is formatted with NTFS.

Custom. The Properties window of certain older Office documents includes this tab, where you can look up a document’s word count, author, revision number, and many other statistics. But you should by no means feel limited to these 21 properties.

Using the Custom tab, you can create properties of your own—Working Title, Panic Level, Privacy Quotient, or whatever you like. Just specify a property type using the Type pop-up menu (Text, Date, Number, Yes/No); type the property name into the Name text box (or choose one of the canned options in its drop-down menu); and then click Add.

You can then fill in the Value text box for the individual file in question (so that its Panic Level is Red Alert, for example).

Note:

This is an older form of tagging files—a lot like the tags feature described in “Tags, Metadata, and Properties”—except that you can’t use the Search feature to find them. Especially technical people can, however, perform query-language searches for these values.

The Details tab reveals the sorts of details—tags, categories, authors, and so on—that are searchable by Windows’ Search command. For many kinds of files, you can edit these little tidbits right in the dialog box.

This box also tells you how many words, lines, and paragraphs are in a particular Word document. For a graphics document, the Summary tab indicates the graphic’s dimensions, resolution, and color settings.

The Previous Versions tab appears only if you’ve gone to the extraordinary trouble of resurrecting Windows 7’s Previous Versions feature, which lets you revert a document or a folder to an earlier version.

Folders

The Properties dialog box for a folder offers a bunch of tabs:

General, Security. Here you find the same sorts of checkboxes and options as you do for data files, described already.

Sharing makes the folder susceptible to invasion by other people—either in person, when they sign into this PC, or from across your office network (see Chapter 19).

Location. This tab appears only for folders you’ve included in a library (“Libraries”). It identifies where the folder really sits.

Customize. The first drop-down menu here lets you apply a folder template to any folder: General items, Documents, Pictures, Music, or Videos. A template is nothing more than a canned layout with a predesigned set of Ribbon tabs, icon sizes, column headings, and so on.

You may already have noticed that your Pictures library displays a nice big thumbnail icon for each of your photos, and that your Music library presents a tidy Details-view list of all your songs, with Ribbon buttons like “Play all,” “Play To,” and “Add to playlist.” Here’s your chance to apply those same expertly designed templates to folders of your own making.

This dialog box also lets you change the icon for a folder, as described in the next section.

Program files

There’s not much here you can change yourself, but you certainly get a lot to look at. For starters, there are the General and Details tabs described already. But you may also find an important Compatibility tab, which may one day come to save your bacon. It lets you trick a pre–Windows 10 program into running on Microsoft’s latest.

Changing Your Icon Pictures

You can change the actual, inch-tall illustrations that Windows uses to represent the little icons in your electronic world. You can’t, however, use a single method to do so; Microsoft has divided up the controls between two different locations.

Standard Windows icons

First, you can change the icon for some of the important Windows desktop icons: the Recycle Bin, Documents, and so on. To do so, right-click a blank spot on the desktop. From the shortcut menu, choose Personalize.

In the resulting window, click Themes in the task pane at the left side; then click “Desktop icon settings.” You’ll see a collection of those important Windows icons. Click one and then click Change Icon to choose a replacement from a collection Microsoft provides. (You haven’t lived until you’ve made your Recycle Bin look like a giant blue thumbtack!)

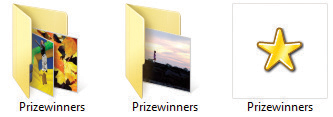

Folder or shortcut icons

Ordinarily, when your Explorer window is in Tiles, Content, or a fairly big Icon view, each folder’s icon resembles what’s in it. You actually see a tiny photo, music album, or Word document peeking out of the open-folder icon.

This means, however, that the icon may actually change over time, as you put different things into it. If you’d rather freeze a folder’s icon so it doesn’t keep changing, you can choose an image that will appear to peek out from inside that folder.

Note:

The following steps also let you change what a particular shortcut icon looks like. Unfortunately, Windows offers no way to change an actual document’s icon.

Actually, you have two ways to change a folder’s icon. Both begin the same way: Right-click the folder or shortcut whose icon you want to change. From the shortcut menu, choose Properties, and then click the Customize tab. Now you have a choice (Figure 3-9):

Change what image is peeking out of the file-folder icon. Click Choose File. Windows now lets you hunt for icons on your hard drive. These can be picture files, icons downloaded from the Internet, icons embedded inside program files and .dll files, or icons you’ve made yourself using a freeware or shareware icon-making program. Find the graphic, click it, click Open, and then click OK.

Figure 3-9. Left: The original folder icon.

Middle: You’ve replaced the image that seems to be falling out of it.

Right: You’ve completely replaced the folder icon.It may take a couple of minutes for Windows to update the folder image, but soon you’ll see your hand-selected image “falling out” of the file-folder icon.

Completely replace the file-folder image. Click Change Icon. Windows offers up a palette of canned graphics; click the one you want, and then click OK. Instantly, the original folder bears the new image.

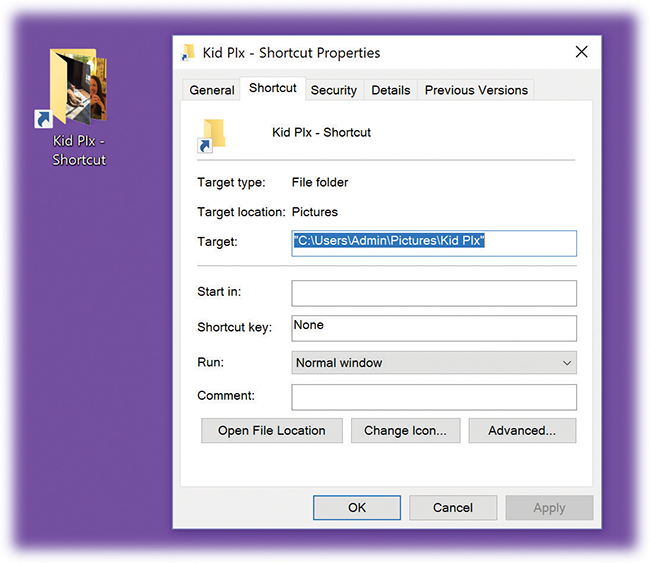

Shortcut Icons

A shortcut is a link to a file, folder, disk, or program (see Figure 3-10). You might think of it as a duplicate of the thing’s icon—but not a duplicate of the thing itself. (A shortcut occupies almost no disk space.) When you double-click the shortcut icon, the original folder, disk, program, or document opens. You can also set up a keystroke for a shortcut icon so you can open any program or document just by pressing a certain key combination.

Figure 3-10. Left: You can distinguish a desktop shortcut from its original in two ways. First, the tiny arrow “badge” identifies it as a shortcut; second, its name contains the word “Shortcut.”

Right: The Properties dialog box for a shortcut indicates which actual file or folder this one “points” to. The Run drop-down menu lets you control how the window opens when you double-click the shortcut icon.

Shortcuts provide quick access to the items you use most often. And because you can make as many shortcuts of a file as you want, and put them anywhere on your PC, you can, in effect, keep an important program or document in more than one folder. Just create a shortcut to leave on the desktop in plain sight, or drag its icon onto the Links toolbar. In fact, every link in the top part of your navigation pane is a shortcut.

Note:

Don’t confuse the term shortcut, which refers to one of these duplicate-icon pointers, with shortcut menu, the context-sensitive menu that appears when you right-click almost anything in Windows. The shortcut menu has nothing to do with the shortcut icons feature; maybe that’s why it’s sometimes called the context menu.

Among other things, shortcuts are great for getting to websites and folders elsewhere on your network, because you’re spared having to type out their addresses or burrow through network windows.

Creating and Deleting Shortcuts

To create a shortcut, use any of these tricks:

Right-click (or hold your finger down on) an icon. From the shortcut menu, choose “Create shortcut.”

Right-drag an icon from its current location to the desktop. (On a touchscreen, hold your finger on the icon momentarily before you drag.)

When you release the mouse button or your finger, choose “Create shortcuts here” from the menu that appears.

Tip:

If you’re not in the mood to use a shortcut menu, then just left-drag an icon while pressing Alt. A shortcut appears instantly. (And if your Alt key is missing or broken—hey, it could happen—then drag while pressing Ctrl+Shift instead.)

Copy an icon, as described earlier in this chapter. Open the destination window; then, on the Ribbon’s Home tab, click “Paste shortcut.”

Drag the tiny icon at the left end of the address bar onto the desktop or into a window.

Tip:

This also works with websites. If your browser has pulled up a site you want to keep handy, drag that little address-bar icon onto your desktop. Double-clicking it later will open the same web page.

You can delete a shortcut the same way as any icon, as described in the Recycle Bin discussion in “Copying with Copy and Paste”. (Of course, deleting a shortcut doesn’t delete the file it points to.)

Unveiling a Shortcut’s True Identity

To locate the original icon from which a shortcut was made, right-click the shortcut icon and choose Properties from the shortcut menu. As shown in Figure 3-10, the resulting box shows you where to find the “real” icon. It also offers you a quick way to jump to it, in the form of the Open File Location button.

Shortcut Keyboard Triggers

Sure, shortcuts let you put favored icons everywhere you want to be. But they still require clicking to open, which means taking your hands off the keyboard—and that, in the grand scheme of things, means slowing down.

Lurking within the Shortcut Properties dialog box is another feature with intriguing ramifications: the “Shortcut key” box. By clicking here and then pressing a key combination, you can assign a personalized keystroke for the shortcut. Thereafter, by pressing that keystroke, you can summon the corresponding file, program, folder, printer, networked computer, or disk window to your screen, no matter what you’re doing on the PC. It’s really useful.

Three rules apply when choosing keystrokes to open your favorite icons:

The keystrokes work only on shortcuts stored on your desktop. If you stash the icon in any other folder, the keystroke stops working.

Your keystroke can’t incorporate the space bar or the Enter, Backspace, Delete, Esc, Print Screen, or Tab keys.

Your combination must include Ctrl+Alt, Ctrl+Shift, or Alt+Shift, and another key.

Windows enforces this rule rigidly. For example, if you type a single letter into the box (such as E), Windows automatically adds the Alt and Ctrl keys to your combination (Alt+Ctrl+E). This is the operating system’s attempt to prevent you from inadvertently duplicating one of the built-in Windows keyboard shortcuts and thoroughly confusing both you and your computer.

Tip:

If you’ve ever wondered what it’s like to be a programmer, try this. In the Shortcut Properties dialog box (Figure 3-10), use the Run drop-down menu at the bottom of the dialog box to choose “Normal window,” “Minimized,” or “Maximized.” By clicking OK, you’ve just told Windows what kind of window you want to appear when opening this particular shortcut.

Controlling Windows in this way isn’t exactly the same as programming, but you are, in your own small way, telling Windows what to do.

If you like the idea of keyboard shortcuts for your files and programs, but you’re not so hot on Windows’ restrictions, then consider installing a free macro program that lets you make any keystroke open anything anywhere. The best-known one is AutoHotkey, which is available from this book’s “Missing CD” page at www.missingmanuals.com, but there are plenty of similar (and simpler) ones. Check them out at, for example, www.shareware.com.

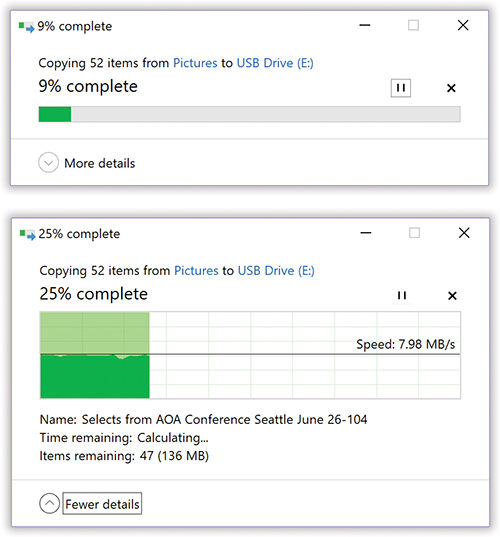

Copying and Moving Folders and Files

Windows offers two techniques for moving files and folders from one place to another: dragging them and using the Copy and Paste commands. In both cases, you’ll be delighted to find out how communicative Windows is during the copy process (Figure 3-11).

Whichever method you choose, you start by showing Windows which icons you want to copy or move—by highlighting them, as described in “Selecting Icons”. Then proceed as follows.

Copying by Dragging Icons

You can drag icons from one folder to another, from one drive to another, from a drive to a folder on another drive, and so on. (When you’ve selected several icons, drag any one of them, and the others will go along for the ride.)

Here’s what happens when you drag icons in the usual way, using the left mouse button:

Dragging to another folder on the same disk moves the folder or file.

Dragging from one disk to another copies the folder or file.

Holding down the Ctrl key while dragging to another folder on the same disk copies the file. (If you do so within a single window, Windows creates a duplicate of the file called “[Filename] - Copy.”)

Pressing Shift while dragging from one disk to another moves the folder or file (without leaving a copy behind).

Tip:

You can move or copy icons by dragging them either into an open window or directly onto a disk or folder icon.

Figure 3-11. Windows is a veritable chatterbox when it comes to copying or moving files.

Top: For each item you’re copying, you see a graph and a percentage-complete readout. There’s a Pause button and a Cancel button (the  ). And there’s a “More details” button.

). And there’s a “More details” button.

Bottom: “More details” turns out to be an elaborate graph that shows you how the speed has proceeded during the copy job. The horizontal line indicates the average speed, in megabytes per second.

Any questions?

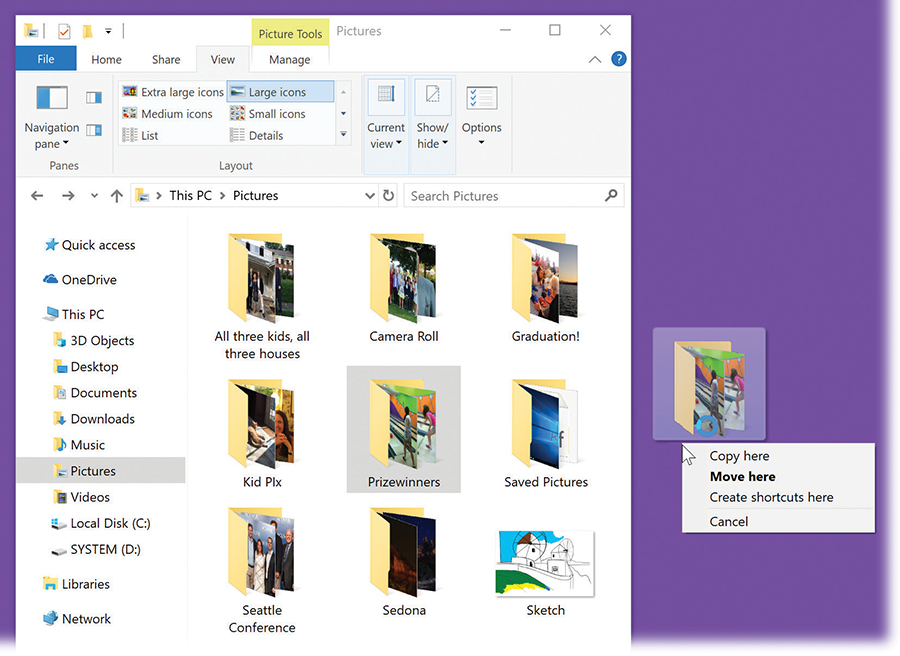

The right-mouse-button trick

Think you’ll remember all those possibilities every time you drag an icon? Probably not. Fortunately, you never have to. One of the most important tricks you can learn is to use the right mouse button as you drag. When you release the button, the menu shown in Figure 3-12 appears, letting you either copy or move the selected icons.

Copying or Moving Files with the Ribbon

Dragging icons to copy or move them feels good because it’s so direct; you actually see your arrow cursor pushing the icons into the new location.

But you pay a price for this satisfying illusion. That is, you may have to spend a moment or two fiddling with your windows, or clicking in the Explorer folder hierarchy, so you have a clear “line of drag” between the icon to be moved and the destination folder.

But, these days, moving or copying icons can be a one-step operation, thanks to the “Move to” and “Copy to” buttons on the Ribbon’s Home tab. The drop-down menu for each one lists frequently and recently used folders. (If the destination folder isn’t listed, then choose “Choose location” and navigate to it yourself.)

In other words, you just highlight the icons you want to move, hit “Move to” or “Copy to,” and then choose the destination folder. The deed is done, without ever having to leave the folder window where you began.

Copying with Copy and Paste

You can also move icons from one window into another using the Cut, Copy, and Paste commands. The routine goes like this:

Highlight the icon or icons you want to move.

Use any of the tricks described in “Selecting Icons”.

Right-click (or hold your finger down on) one of the icons. From the shortcut menu, choose Cut or Copy.

You may want to learn the keyboard shortcuts for these commands: Ctrl+C for Copy, Ctrl+X for Cut. Or use the Cut and Copy buttons on the Ribbon’s Home tab.

The Cut command makes the highlighted icons appear dimmed; you’ve stashed them on the invisible Windows Clipboard. (They don’t actually disappear from their original nesting place until you paste them somewhere else—or hit the Esc key to cancel the operation.)

The Copy command also places copies of the files on the Clipboard, but it doesn’t disturb the originals after you paste.

Right-click the window, folder icon, or disk icon where you want to put the icons. Choose Paste from the shortcut menu.

Once again, you may prefer to use the appropriate Ribbon button, Paste, or the shortcut, Ctrl+V.

Either way, you’ve successfully transferred the icons. If you pasted into an open window, you see the icons appear there. If you pasted onto a closed folder or disk icon, you need to open the icon’s window to see the results. And if you pasted right back into the same window, you get a duplicate of the file called “[Filename] - Copy.”

The Recycle Bin