Chapter 10. Analytics

If they will not understand that we are bringing them a mathematically infallible happiness, we shall be obliged to force them to be happy.

Optimize.

That’s such a nice word. Optimize. Make something the best it can be. Who doesn’t want to do that?

Now that you’ve done all of the hard work designing and developing your site, service, or application, you want to make sure it’s the best. You want to optimize it. Optimizing a design is the chief aim of quantitative research and analysis. There are a lot of people out there who—in exchange for your money—want to help you do this.

When you set out to optimize, you will run up against one of the oldest and thorniest philosophical problems, that of the Good. What is good? How do you know it’s good? What does it mean to be best? What are you optimizing for? How will you know when you have attained that optimal state and have reached the best of all possible worlds?

What if, in optimizing for one thing, you cause a lot of other bad things to happen?

Optimistic people talk as though there is some sort of obvious, objective standard—but once you start thinking about what is truly optimal, you will find that it’s always subjective and you’ll always have to make trade-offs. This is why designers will never be replaced by machines.

Math, Again

Qualitative research methods such as ethnography and usability testing can get you far. You’ll begin to understand how people make decisions and may even get a peek at habits they might not fully admit to themselves. (“Huh, I guess TMZ is in my browser history a lot.”) You can use these insights to design sensible, elegant systems primed for success.

And then you release your work into the world to see how right you were—and the fun begins. No matter how much research and smart design thinking you did up front, you won’t get everything right out of the gate, and that’s okay. Because here come the data...I mean, the visitors.

Once your website or application is live and users arrive in significant numbers, you’ll start getting some quantitative data. (If no one shows up, please consult your marketing strategy.) Every interaction each of those individuals has with your website can be measured. All of the people with the particular needs and quirks you lovingly studied fade away in the face of the faceless masses.

You were in the realm of informed assertions. Now you’re in the big time. Actual data. You can see how well your design is performing out there in the world. How many people? How long do they stay? What do they see? Where do they exit? Do they return? How frequently? And do they click the button?

Once you can measure your success in numerical terms, you can start tweaking. The elements of your design become so many knobs and levers you can manipulate to get to the level of success you’d envisioned, and beyond.

Preaching to the converted

The term for clicking the button—you know, the button—is conversion. A user is said to convert any time they take a measurable action you’ve defined as a goal of the site. For many websites there is an obvious primary raison d’être. On a marketing website, conversion is clicking “sign up”; for ecommerce sites, “buy now”; on a hotel site, “make a reservation.” The success of the design can be measured by how many people click that button and do the thing that makes the money.

Some websites are completely optimized for simple conversion, and it’s easy to tell. The design centers on one clear call to action, a vivid lozenge labeled with a verb. The usual picture is a little more complex, with several different types of conversion. Which converts do you want the most?

A site or app might offer several potential actions with desirable outcomes: newsletter sign-up, advance ticket sales, online shopping, becoming a member. Measuring the conversion rate for each of these will indicate the success of that particular path, but not how each type of conversion matters to the success of the organization itself. That is a business decision.

Ease into Analytics

As soon as you have some data, you can start looking for trends and patterns. It might be a little overwhelming at first, but this sort of direct feedback gets addictive fast. Decision-makers love data, so being handy with the stats can be to your advantage in arguments. Sure, that involves math, but people who love math have built some tools to make it easy—and you’re going to need to use them unless you’re really keen on analyzing raw server logs yourself.

Analytics refers to the collection and analysis of data on the actual usage of a website or application—or any quantifiable system—to understand how people are using it. Based on data from analytics, you can identify areas where your website is not as effective as you’d like it to be. For example, analytics could tell you that a thousand people visit the homepage every day, but only five people click on any other link on the page. Whether this is a problem depends on your goals for the site. You can make changes and then check these measurements, or metrics, again to see whether your changes have had an effect.

If you would like more people to sign up for the newsletter from the homepage, you could try making the link to the newsletter sign-up more visually prominent, then check the analytics again.

At the time of writing, over thirty-five million of the world’s most popular websites have Google Analytics installed, according to technology trends website builtwith.com. Google Analytics is an excellent place to start your journey towards mathematical perfection and will give you a variety of pleasing charts and graphs. After you sign up, you or a friendly developer will need to insert a snippet of JavaScript into the source code of the site you want to measure.

Keep two things in mind when you consider analytics: goals and learning. The specific metrics to track will depend on your audience and business goals. Just because something is measurable doesn’t make it meaningful; tracking the wrong metrics can be worse than not tracking any. If you don’t already have quantitative goals, define some. You can start by looking up averages for your type of site or industry; those are the numbers to beat.

The whole point is to learn about the performance of your system so you can meet your goals. Otherwise, it’s easy to see your success reflected in a funhouse mirror of vanity metrics—big numbers devoid of context that tell you nothing. As with Net Promoter Score from Chapter 9, you could end up trying to optimize specific numbers, chasing correlations without finding the why, and losing site of the larger picture.

Depending on the role any part of your online presence plays in your overall strategy for success, raw numbers might not mean anything useful. Your primary website might be strategically important, but never reach beyond the niche audience for which it’s intended.

Some of the most interesting data points aren’t about what’s happening on your website at all, but where your traffic is coming from, and how your work is affecting things out in the world.

Having enough metrics is no longer the issue it once was. The question is what to do with them. If you aren’t making your numbers, review the data and prioritize changes. For web sites, bounce rate—the proportion of visitors who leave after viewing one page—is a good place to start. Before you get around to fine-tuning your message, you need people to stick around long enough to hear it. A high bounce rate is often an indicator of unmet expectations or uncertainty about where to go next.

You can use analytics to see which pages are the most frequent entry points. Then review those pages for clarity. If you know what you want visitors to do, make sure that’s coming through in the design and content of the page. How do you make sure? Well, you can do some usability testing to get more insight into the potential problems. Or venture into the statistical wonderland of split testing.

Lickety-Split

There are many solutions to every problem. If your problem is getting as many people as possible to sign up for the newsletter, there might be some debate over the most effective change to make to the site. To solve your dilemma, you could try split testing.

A split test is a clinical trial for a particular page or set of elements on your website. Some visitors are served the control—the current design—and others get a variation. The variation that performs significantly better for a specific metric is the winner. Then you can either decide to switch all traffic to the winner, or put it up against another challenger or set of challengers.

This method is called split testing because you split your traffic programmatically and randomly serve variations of a page or element on your site to your users. Maybe one half gets the current homepage design with a sign-up button to the right of the call to action, and the other half sees the exact same page with a sign-up button underneath the call to action. On the horizon, the clouds part and you can see all the way to Mount Optimal, that mythical realm of mathematical perfection.

Like an international criminal, split testing has a lot of aliases, including A/B testing, A/B/n testing, bucket testing, multivariate testing, and the Panglossian “whole site experience testing,” which promises to deliver the best of all possible website experiences. Each of these denotes a variation on the same basic idea.

This approach is of special interest to marketers, and actually derives from a technique first used in ancient times when special offers were sent on paper by direct mail. Send a flyer with one offer (“Free dessert with every pizza”) to a thousand houses, and a flyer with a different offer (“Free salad with every pizza”) to a thousand other houses, and see which one generates the better response.

There is both an art and a science, and quite a lot of statistics, to using split testing effectively and appropriately. As a designer, you may be asked to participate in the process or create variations. Even if you aren’t in charge of running them, it’s helpful to know the basics so you can deal with the effects.

The split-testing process

At last, SCIENCE. Bust out that lab coat, because you will be running experiments.

The general outline of events for split testing is as follows:

- Select your goal.

- Create variations.

- Choose an appropriate start date.

- Run the experiment until you’ve reached a ninety-five-percent confidence level.

- Review the data.

- Decide what to do next: stick with the control, switch to the variation, or run more tests.

You will need a specific, quantifiable goal. This is a track race, not rhythmic gymnastics—no room for interpretation. You have to know the current conversion rate (or other metric) and how much you want to change it. For example, five percent of all site visitors click on “Buy tickets,” and we want to increase the conversion rate to seven percent.

Next, determine how much traffic you need. The average number of visitors your site gets is important for a couple of reasons. Small, incremental changes will have a more significant influence on a high-traffic site (one percent of one million versus one percent of one thousand) and tests will be faster and more reliable with a larger sample size. How large a sample do you need? It depends on the sensitivity of the test and how large an improvement you want to see. If you are looking at making a small change, you will need a larger sample to make sure you can be confident in the result. A small change in a small sample size is more likely to be merely the result of chance.

Approach this process with patience and confidence. The confidence in this case is statistical confidence—the probability that the winner is really the winner—rather than the outcome of chance events. The standard is ninety-five percent, meaning there is a ninety-five percent chance you can rely on the result. On a high-traffic site, you can get to this level within a couple of days; lower traffic, and the test will take longer.

To rule out the effect of other variables, such as the day of the week, you would ideally let the test run over a two-week holiday-free period, allowing you to make day-over-day comparisons. You also need to let the test run long enough to counter unexpected outliers; perhaps your organization received an unexpected mention in the New York Times, and the website variation you’re testing is particularly popular with Times readers but not with the typical population of your site’s visitors. The less patience you have, the more you open yourself up to errors, both false positives and false negatives.

It’s also important to keep in mind that if you want to test variations of a particular page against the current state, someone has to design those variations. Even if they’re small changes, it’s still work.

If you’re testing a landing page with one call to action—one button a user can click on—you can change any aspect of that page with regard to that one measurement, including:

- The wording, size, color, and placement of the button.

- Any piece of copy on the page and the total amount of copy.

- The price or specific offer.

- The image or type of image used (photo versus illustration).

The winner is often counterintuitive, in a “Who would have thought brown buttons would work the best with this audience?” sort of way. If there’s agreement about which metric you’re optimizing for and the math is sound, it’s an opportunity to learn.

After a number of tests, you may see patterns begin to emerge that you can apply to your design work when solving for specific conversion goals. By the same token, remember that specific conversion goals are frequently just one aspect of the overall success of a website or business.

Cautions and considerations

More precautions apply to split testing than to most other information-gathering approaches, for a couple of reasons. Testing can be seductive because it seems to promise mathematical certitude and a set-it-and-forget-it level of automation, even though human decision-making is still necessary and the results remain open to interpretation within the larger context. The best response to a user-interface question is not necessarily a test. Additionally, these are activities that affect the live site itself, which presents some risk.

Much like Dr. Frankenstein, you have set up your laboratory in the same place you receive visitors, so it’s important to design and run your experiments in a way that doesn’t disrupt what’s already working well. A consistent online experience can help build trust and habit, and split testing by its very nature introduces inconsistency. Keep this in mind as you decide what and how to test.

This is an incremental process—tweaking and knob-twiddling—and not a source of high-level strategic guidance. Since you’re changing things up, it’s best suited for aspects of your design where users might expect to see variation, and where there is a single clear user behavior you want to elicit in a given context. Search engine marketing landing pages? Fantastic. Those are generally intended for new users. Global navigation? Maybe not.

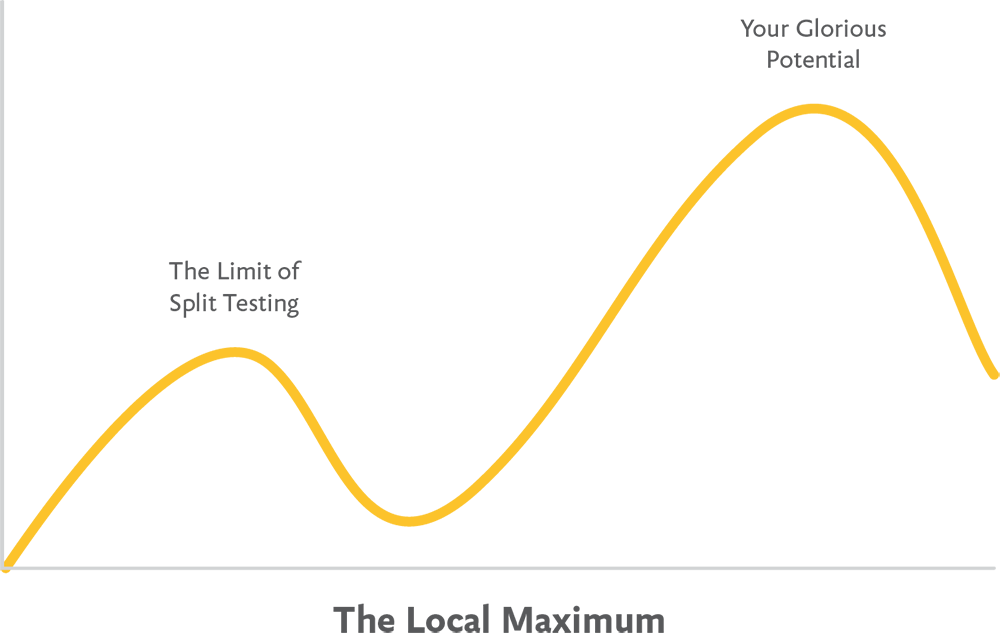

Focusing on small positive changes can lead to a culture of incrementalism and risk aversion. How will you ever make a great leap that might have short-term negative effects? On his excellent blog, entrepreneur and adviser Andrew Chen invokes the concept of the local maximum, which you may be excited to remember from calculus (http://bkaprt.com/jer2/10-01/). The gist is that you can only do so much optimizing within an existing design system. If you focus on optimizing what you have rather than also considering larger innovations, who knows what vastly greater heights you might miss (Fig 10).

This is why understanding context and qualitative factors matters. All the split testing in the world never managed to turn Yahoo! into Google. And all of Google’s mathematical acumen didn’t save Google+ from the dustbin of also-ran social media experiments. You always need to answer “Why?” before asking “How?” And you need good answers for both.

Designers and Data Junkies Can Be Friends

We admire Mr. Spock for his logical Vulcan acumen but find him relatable because of his human side.

There is a tension between strategic design thinking and data-driven decision-making. In the best case, this is a healthy tension that respects informed intuition and ambitious thinking and knows how to measure success. When data rules the roost, this can leave designers feeling frustrated and undervalued.

The best teams are Spock-like. They embrace data while encouraging and inspiring everyone working on a product to look beyond what can be measured to what might be valued.

You can optimize everything and still fail, because you have to optimize for the right things. That’s where reflection and qualitative approaches come in. By asking why, we can see the opportunity for something better, beyond the bounds of the current best.

Even math has its limits.