Chapter 3. The Process

This is the “systematic” in the systematic inquiry. Whether the research requires a month or a single morning, being just a bit methodical will be the “extra” step that saves your precious time and brain. Whatever type of research you’re doing, and wherever it falls in your schedule, follow these six steps:

- Define the problem.

- Select the approach.

- Plan and prepare for the research.

- Collect the data.

- Analyze the data.

- Report the results.

With practice, the first three steps will become muscle memory and you can focus on collecting, analyzing, and sharing the data.

1. Define the Problem

Just as you need a clearly articulated problem to create a solid design solution, a useful research study depends on a clear problem statement. In design, you’re solving for user needs and business goals. In research, you’re solving for a lack of information. A research problem statement describes your topic and your goal.

You want to know when you’re finished, right? So base your statement on a verb that indicates an outcome, such as “describe,” “evaluate,” or “identify.” Avoid using open-ended words like “understand” or “explore.” You’ll know when you have described something. Exploration is potentially infinite.

For example, if your topic is working parents of school-aged children and your research question is, “How do they select and plan weekend activities?” then your problem statement could be, “We will describe how parents of school-age children select and plan weekend activities.” Or, if your topic is your competitors and your research question is, “What are their competitive advantages and disadvantages relative to our service?” the corresponding problem statement might be, “We will analyze the relative advantages and disadvantages of a set of identified competitors.”

The most significant source of confusion in design research is the difference between research questions and interview questions. This confusion costs time and money and leads to a lot of managers saying that they tried doing research that one time and nothing useful emerged.

Your research question and how you phrase it determines the success and utility of everything that follows. If you start with a bad question, or the wrong question, you won’t end up with a useful answer. We understand this in daily life, but talking about research in a business context seems to short-circuit common sense. Everyone is too worried about looking smart.

Your research question is simply what you want to find out in order to make better evidence-based decisions. A good research question is specific, actionable, and practical. This means:

- it’s possible to answer the question using the techniques and methods available to you, and

- it’s possible (but not guaranteed) to arrive at an answer with a sufficient degree of confidence to base decisions on what you’ve learned.

If your question is too general or just beyond your means to answer, it is not a good research question. “How’s the air on Mars?” may be a practical question for Elon Musk to answer, but it isn’t for most of us.

You might have a single question, a question with several subquestions, or a group of related questions you want to answer at the same time. Just make sure they add up to a clear problem statement. That discipline will help you figure out when and whether you’ve learned what you set out to learn.

Now that you’ve identified what you want to find out, you can move on to how.

2. Select the Approach

Your problem statement will point you toward a general type of research. The amount of resources at your disposal (time, money, people) will indicate an approach. There are a lot of ways to answer a given question, and they all have trade-offs.

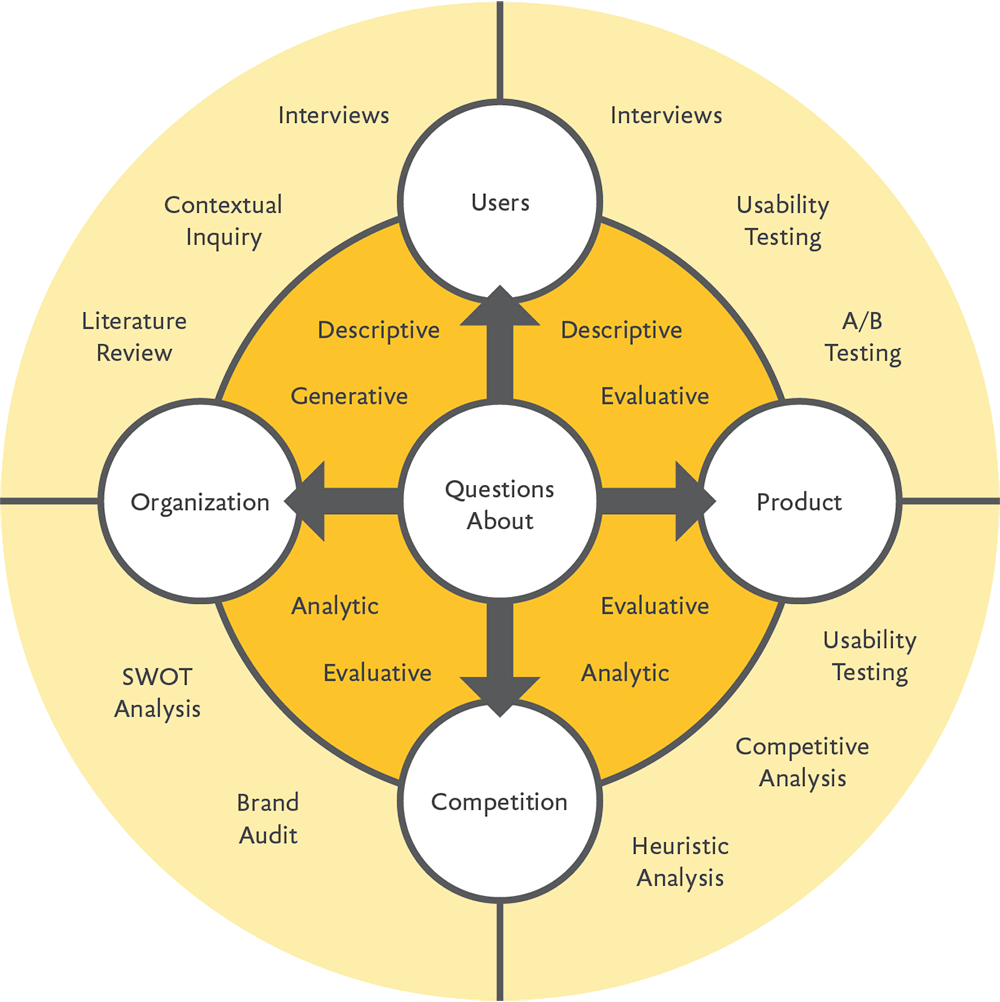

If your question is about users themselves, you’ll be doing user research, or ethnography (see Chapter 5). If you want to assess an existing or potential design solution, you’ll be doing some sort of evaluative research (see Chapter 7). As a single question comes into focus, you might conduct multiple studies or take one of several potential approaches (Fig 3).

Once you’ve selected the approach, write a quick description of the study by incorporating the question. For example: “We will describe how parents of school-age children select and plan weekend activities by conducting telephone interviews and compiling the results.”

3. Plan and Prepare for the Research

First of all, identify the point person—the person responsible for the plan, the keeper of the checklist. This can be anyone on the team, whether or not they’re participating in the research; it just has to be one person. This will help keep things from falling through the cracks.

Sketching out an initial plan can be very quick if you’re working by yourself or with a small group. Decide how much time and money you will be devoting to research, and who will be involved in which roles. Identify subjects and, if necessary, decide how you’re going to recruit them. Include a list of materials.

In the beginning, don’t worry about getting everything right. If you don’t know, go with your best guess. Since research is about seeking out new information, you’re going to encounter new situations and unpredictable circumstances. Make friends with the unexpected. And prepare to change the plan you’ve made to adapt once you have facts.

You might plan for sixty-minute sessions but find that you’re getting all the information you need in half an hour. Or you might find that the name of a particular competitor keeps coming up during an interview, so you decide to add fifteen minutes of competitive usability testing to the interview so you can observe your target customers using your competitor’s service.

Just be very clear about the points at which changes to your research plans might affect your larger project. It’s easy to be optimistic, but it’s more helpful to think about trade-offs and fallback plans in a cool moment before you get started. What will you do if recruiting and scheduling participants looks like it’s going to take longer than you’ve planned? You can push out the dates, relax your criteria for participants, or talk to fewer people now and try for more later. There’s no one right answer—only the best way to meet your overall project goals at the time.

In addition to answering your research questions, you’ll continue to learn more about research itself. Each activity will make you smarter and more efficient. So much win.

Your research plan should include your problem statement, the duration of the study, who will be performing which roles, how you will target and recruit your subjects, plus any incentives or necessary tools and materials.

This is just the start. You can always add more details as they become helpful to you or your team.

Recruiting

Once you know what you need to know, you can identify whom to study to help fill in those gaps. Recruiting is simply locating, attracting, screening, and acquiring research participants.

Good recruiting puts the quality in your qualitative research. It is tempting to take shortcuts, but these add up to a bad practice over time. You need the individual participants to be as good as they can be. Participants are good to the extent that they represent your target. If participants don’t match your target, your study will be useless. You can learn valuable things by asking the right people the wrong questions. If you’re talking to the wrong people, it doesn’t matter what you ask. Bad participants can undermine everything you’re trying to do.

A good research participant:

- shares the concerns and goals of your target users,

- embodies key characteristics of your target users, such as age or role,

- can articulate their thoughts clearly, and

- is as familiar with the relevant technology as your target users.

Remember, there is no such thing as a “generic person.” You can be more or less specific, depending on your line of business and your goals. At the same time, don’t make the mistake of going too narrow too quickly—be intentional, not lazy.

In theory, recruiting is just fishing. Decide what kind of fish you want. Make a net. Go to where the fish are. Drop some bait in the water. Collect the ones you want. It isn’t actually that mysterious, and once you get the hang of it, you’ll develop good instincts.

In practice, recruiting is a time-consuming pain in the ass. Embrace it. Get good at it and all of your research will be faster and easier, plus this part of the process will get progressively less unpleasant.

When designing web applications or websites, the web is a terrific place to find potential test participants. If you happen to have a high-traffic website you can put a link on, that’s the easiest way to draw people in (unless you need to recruit people who have never been to that site). Otherwise you can email a link to a screener—a survey that helps you identify potential participants who match your criteria—or post the screener where it will be visible.

Go anywhere you’re allowed to post a message that might be seen by your target users or their forward-happy friends and family. Twitter. Craigslist. Facebook. LinkedIn.

If you need people in a certain geographic area, see whether there are local community sites or blogs that would announce it as a service. Referring to it as “design research” rather than “marketing research” goes a long way in the goodwill department.

There are such things as professional recruiters, but it’s best to recruit your own participants unless you have no alternative. Why should the recruiting agency learn the most about your audience?

Screeners

The net is your screener. The bait is the incentive.

A screener is simply a survey with questions to identify good participants and filter out anyone who would just waste your time. This is incredibly important. You can tell a good recruit immediately when you test. Good test participants care. When presented with a task, they get right into the scenario. You could offer a greasy piece of paper with a couple of rectangles scrawled on it and say, “How would you use this interface to buy tickets to a special exhibit?” If you’re talking to someone who buys tickets, by God they will try.

Mismatched participants are as obvious as a bad blind date. Their attention will drift. They will go off on irrelevant tangents about themselves. (“I shoplift for fun.”) You could show them a fully functional, whiz-bang prototype and be met with stares and unhelpful critiques. (“Do all the links have to be blue? I find that really dull.”) And you will find a way to politely shake their hand and send them packing as soon as possible. (With the incentive promised, by the way. It’s not their fault they didn’t get properly screened.)

The most efficient method of screening is an online survey. (See the Resources section for suggested tools for creating surveys and recruiting participants.) To write the screener, you and your team will need to answer the following questions, adapted from an article by Christine Perfetti (http://bkaprt.com/jer2/03-01/):

- What are all of the specific behaviors you’re looking for? Behaviors are the most important thing to screen for. Even if you’re designing something you believe to be totally novel, current behaviors determine whether your design has a chance of being relevant and intelligible to the participants. If you’re designing an app for cyclists, you need to test the app with people who ride bikes, not people who love bikes and wish they had time to ride.

- What level of tool knowledge and access do participants need? Be realistic about the amount of skill and comfort you’re targeting. And if participants need certain equipment or access, make sure to mention that. For instance, to usability-test a mobile app, you need people who are sufficiently familiar with their device to focus on the app’s usability. Otherwise, you might end up testing the phone and get nothing useful.

- What level of knowledge about the topic (domain knowledge) do they need? If you’re truly designing something for very general audiences in a familiar domain—say, reading the news—you should verify that they actually do the activities you’re asking about, but you don’t have to screen for knowledge about the subject matter. On the other hand, if you’re making an iPad app that helps mechanics work on cars, don’t test with brain surgeons.

Writing a screener is a good test of your empathy with your target users. To have reliable results, you need to screen in the right potential participants, screen out the bad matches, and prevent professional research participants from trying to read your mind to get the study incentive. Even a $25 Amazon gift certificate will attract wily dissemblers. Be vague about the contents of the actual test. If you recruit people from the site you are testing, then just refer to “an interview about this website.”

Asking age, gender, and location allows you to avoid certain biases, but you also need to get at differences in behavior patterns that may have implications for your design.

For example, say you’re recruiting for a usability study for a science museum. You might ask the following question:

How frequently do you engage in the following activities? (Answers: never or rarely; at least once a year; a few times per year; at least once a month; at least once a week.)

- Go to the movies.

- Go hiking.

- Go to an amusement park.

- Try a new restaurant.

- Visit a museum.

- See live music or go to a club.

- See other local sights.

- Go out of town for the weekend.

This question serves two purposes: it gauges museum-visiting frequency without giving away the topic of the study, and it offers a way to assess general habits around getting out of the house.

At the same time, you should make the screener as short as possible to reduce the possibility of potential participants bailing before they get to the end. Don’t ask anything on the screener that you can find out searching the web. It usually takes two minutes to look someone up online to see whether they are really a teacher who lives in Nebraska or a crafty scammer trolling for gift cards.

For in-person studies, it’s best to follow up by phone with everyone who made the first cut. Asking a couple of quick questions will weed out axe murderers and the fatally inarticulate and may save you from a very awkward encounter. For example: “I just want to ask a couple more questions to see whether you’re a good match for our study. Could you tell me how you typically decide what to do on your days off?”

If the answer is a terse “I don’t,” or a verbose description of cat-hoarding and revenge fantasies, just reply that you’ll be in touch and follow up with an email thanking them for their interest.

Just like formulating queries in Google, writing screeners and reviewing the results you get makes you better and more accurate at screening. And even if it takes a little time to get it right, all the available online tools sure beat standing on the corner with a clipboard like market researchers still sometimes do.

4. Collect the Data

It’s go time—the research part of the research. Find your research subjects. Conduct your interviews. Do your field observation. Run your usability tests. (We’ll get into the particulars of each activity later on.)

Research makes data. You might have photos, videos, screen captures, audio recordings, and even handwritten notes. This data will originate with an individual. Get the information onto a shared drive as quickly as physics allows. Every researcher has at least once experienced the tragic loss of good data.

If you are in the field and away from internet access, keep a small backup drive with you. Redundancy worked for the space program and a little bit certainly helps here.

The more organized you are in gathering and storing your data, the more effective and pleasant the analysis will be. Any system you’re already using should work as long as it can accommodate files of the size you’re anticipating.

Use a consistent naming convention, such as “Study-Subject Name-Year-Month-Day.” This is another one of those practices that seems obvious, but is easy to forget when you’re in the throes of discovery.

Take a few moments between sessions to check your files and make sure they’re named correctly and saved in the right place, and note your initial impressions while you’re at it. A few quick thoughts while you’re fresh will give you a jump start on your analysis.

Materials and tools

Design researchers used to have to walk up hills both ways in the snow and rig up a forensics lab to do a half-decent study. No more! It’s so easy now. It’s likely the essentials are scattered around your office, or already inside your messenger bag.

Use what you already have first, and go for familiar tools. The trickiest parts of research used to arise from technical difficulties and equipment learning curves. (The saddest research moment is accidentally erasing a session recording.) Over the past few years, a plethora of online research tools and services have cropped up. Be mindful of choosing services that promise to make the whole process effortless. It’s too easy to become addicted to cheap, bad data. And the rush to scale and automate processes can eradicate the very human, somewhat messy interaction you are trying to understand.

Applications and devices are popping up and disappearing every day, so it’s difficult to create a definitive list, but my favorite (currently available) research tools are listed in the Resources section in the back of the book.

Interviewing

A simple interview remains the most effective way to get inside another person’s head and see the world as they do. It is a core research technique with many applications. Once you are comfortable conducting research interviews, you can apply this skill to any situation in which you need to extract information from another person.

Being a good interviewer requires basic social skills, some practice, and a modicum of self-awareness. Introverts might want to start out as observers and notetakers, while extroverts may need to practice shutting up to let the other person talk.

In the research lingo, the type of interview covered in this book is a semi-structured interview, meaning that you will have prepared questions and topics, but not a strict script of questions to ask each participant in the same order and manner. This allows more flexibility to respond to the individual perspective and topics that come up. You might find out some very useful things you would have never thought to ask.

A successful interview is a comfortable interaction for everyone involved that yields the information you were looking for. The keys to success are preparation, structure, and conduct. (For more on interviewing, see Chapter 5.)

Usability testing

Usability testing is simply the process of conducting a directed interview with a representative user while they use a prototype or actual product to attempt certain tasks. The goal is to determine to what extent the product or service as designed is usable—whether it allows users to perform the given tasks to a predetermined standard—and to uncover any serious, resolvable issues along the way.

The sooner and more often you start doing it, and the more people on your team are familiar with the process, the more useful it is. You shouldn’t even think of it as a separate activity, just another type of review to ensure you’re meeting that set of needs. Business review. Design review. Technical review. Usability review.

What usability testing does

If you have a thing, or even a rough facsimile of a thing, you can test it. If your competitor has a thing, you can test that to figure out what you need to do to create a more usable alternative. If you’re about to start redesigning something, usability-testing the current version can provide some input into what works and what doesn’t work about the current version. The test will tell you whether people understand the product or service and can use it without difficulty. This is really important, but not the whole story where a product is concerned. As philosophers would say, usability is necessary, but not sufficient.

Usability testing can:

- uncover significant problems with labeling, structure, mental model, and flow, which will prevent your product from succeeding no matter how well it functions;

- let you know whether the interface language works for your audience;

- reveal how users think about the problems you purport to solve with your design; and

- demonstrate to stakeholders whether the approved approach is likely to meet stated goals.

What usability testing doesn’t do

Some people criticize usability testing because aiming for a usable product can seem tantamount to aiming for mediocrity. But remember, usability is absolutely necessary, even though it is in no way sufficient. If your product isn’t usable, then it will fail. However, usability testing won’t absolve you of your responsibilities as a designer or developer of excellent products and services.

Usability testing absolutely cannot:

- provide you with a story, a vision, or a breakthrough design;

- tell you whether your product will be successful in the marketplace;

- tell you which user tasks are more important than others; or

- substitute for QA-testing the final product.

If you approach usability testing with the right expectations and conduct it early and often, you will be more likely to launch a successful product, and your team will have fun testing along the way. A habit of usability goes hand-in-hand with a habit of creating high-quality products that people like.

No labs, no masters

We live in the future. There is no reason to test in anything called a “usability lab” unless there’s a danger your experiment will escape and start wreaking havoc. A usability lab gives you the illusion of control when what you are trying to find out is how well your ideas work in the wild. You want unpredictability. You want screaming children in the background, you want glare and interruptions and distractions. We all have to deal with these things when we’re trying to check our balances, book travel, buy shoes, and decide where to go for dinner—that is, when we use products and services like the one you’re testing.

Go to where the people are. If you can travel and do this in person, great. If you can do this remotely, also good. If you’re testing mobile devices, you will, ironically, need to do more testing in person.

Just like the corporate VP who is always tweaking the clip art in presentation slides rather than developing storytelling skills, it’s easy for researchers to obsess about the perfect testing and recording setup rather than the scenarios and facilitation. Good participants, good facilitation, and good analysis make a good usability test. You can have a very primitive setup and still get good results. Usability issues aren’t preferences and opinions, but factors that make a given design difficult and unpleasant to use. You want to identify the most significant issues in the least amount of time so you can go back to the drawing board. (For more on usability testing, see Chapter 7.)

Literature review

Recruiting and observing or interviewing people one at a time is incredibly valuable. It can also be time-consuming. If it’s not possible to talk to representative users directly, or if you’re looking for additional background information, you can turn to documented studies by other researchers. Both qualitative studies and surveys can increase your knowledge of the needs and behaviors you should consider.

Look for preexisting research done by your own company or your client, and anything you can find online from a reputable source. Organizations that serve specific populations, such as journalists or senior citizens, often sponsor research and make it publicly available.

The Pew Research Center’s Internet & American Life Project is a free and reputable source of data (http://bkaprt.com/jer2/03-02). As the name implies, the work focuses on Americans, but it’s a terrific place to start. Pew’s work is typically survey-based, and good for thinking about trends. (Also, their reports offer a model of good communication about findings.)

You can use these studies in a few ways:

- to inform your own general understanding of your target users and help you formulate better questions

- to validate general assumptions

- to complement your work

When working with third-party literature, take these grains of salt:

- Note the questions they were asking and determine to what extent they align with your own.

- Check the sample and note the extent to which it maps to your target user base.

- Check the person or organization conducting and underwriting the study, so you can note their biases.

- Check the date to note whether anything significant has changed since the research was done, such as a new product launch or shift in the economy.

5. Analyze the Data

What does it all mean? Once you have collected the data, gather it all together and look for meaningful patterns. Turn the patterns into observations; from those, recommendations will emerge.

Refer to your initial problem statement and ask how the patterns answer the questions you originally posed. You can use the same qualitative data in different ways and for different purposes. For example, stakeholder interviews might yield business requirements for a redesign and a description of the current editorial workflow that you can use as inputs to the content strategy. Usability testing might indicate issues that need to be fixed, as well as data about current customers that you can use to develop personas.

Returning to data from previous studies can yield new insights as long as the conditions under which they were conducted remain relevant and new questions arise.

Get everyone involved

If you are working with a design team, get as many members as possible involved in the analysis. A group can generate more insights faster, and those insights will be shared and internalized far more effectively than if you simply circulate a report.

Rule of thumb: include people who are able to contribute to a productive session and will benefit from participating. Exclude people who will be a distraction, or who will benefit more from reviewing the results of the analysis.

At a minimum, include everyone who participated directly in the interview process. In the best-case scenario, involve the entire core project team—anyone who will be designing or coding. Working together to examine specific behaviors and concerns will help your team be more informed, invested, and empathetic with users from the start. At the end of the session, you can decide which outcomes from the analysis would be most useful to share up and across.

Structuring an analysis session

Analysis is a fun group activity. You get into a room with your team, review all the notes together, make observations, and turn those into actionable insights. Expect this to take anywhere from half a day to a few days, depending on the number and extent of the interviews. It will save time if you give all of the participants advance access to the notes or recordings so they can come prepared.

Even if the session includes only one interviewer and one notetaker, it’s useful to follow an explicit structure to make sure that you cover everything and work productively. Here’s a good baseline structure. Feel free to modify it to suit your project’s needs:

- Summarize the goals and process of the research. (What did you want to find out? Who from your side participated and in which roles?)

- Describe whom you spoke with and under which circumstances (number of people, on the phone or in person, etc.).

- Describe how you gathered the data.

- Describe the types of analysis you will be doing.

- Pull out quotes and observations.

- Group quotes and observations that typify a repeated pattern or idea into themes. For example, “participants rely on pen and paper to aid memory,” or “parents trust the opinions of other parents.”

- Summarize findings, including the patterns you noticed, the insights you gleaned from these patterns, and their implications for the design.

- Document the analysis in a shareable format.

This work can get a little intense. To proceed smoothly and stay focused, require everyone who participates to agree to the following ground rules (and feel free to add house rules of your own):

- Acknowledge that the goal of this exercise is to better understand the context and needs of the user. Focus solely on that goal.

- Respect the structure of the session. Refrain from identifying larger patterns before you’ve gone through the data.

- Clearly differentiate observations from interpretations (what happened versus what it means).

- No solutions. It will be very tempting to propose solutions. Stick to insights and principles. Solutions come next.

What you’ll need

Sufficient time and willing colleagues are the most essential assets for solid analysis. Once you have those, gather a few more additional office supplies:

- a big room with a lot of whiteboard wall space

- sticky notes (in different colors if you want to get fancy)

- pens

- a camera so you can take pictures of the whiteboard, walls of notes, etc., rather than copy everything down (Also, photos of the session are fun for project retrospectives and company stock photography. “Look, thinky collaborative work!”)

Feel free to group your observations in a number of different ways until your team reaches agreement on the best groupings—by user type, by task type, by importance for product success, etc. The most useful groupings are based on patterns that emerge, rather than those imposed or defined before beginning analysis. If necessary, assign a time limit and take a vote when the time is up.

What is the data?

You are looking for quotes and observations that indicate the following ideas:

- goals (what the participant wants to accomplish that your product or service is intended to help them with or otherwise relates to)

- priorities (what is most important to the participant)

- tasks (actions the participant takes to meet their goal)

- motivators (the situation or event that starts the participant down the task path)

- barriers (the person, situation, or thing that prevents the participant from doing the task or accomplishing the goal)

- habits (things the participant does on a regular basis)

- relationships (the people the participant interacts with when doing the tasks)

- tools (the objects the participant interacts with while fulfilling the goals)

- environment (contextual factors influencing the participant’s motivations and abilities)

Outliers

No matter how rigorous your screening, some outliers may have slipped through. You will know a participant is an outlier if their behaviors and attributes rule them out as a target user or customer. If you have interviewed people who don’t match your design target, note this fact and the circumstances for future recruiting and set the data aside.

For example, imagine that as a part of a research project about enthusiastic sports fans you interview “Dan,” a math teacher who doesn’t follow sports. It turns out that he clicked on the screener while doing some research for a class activity about statistics.

If your target users are sports fans, and Dan doesn’t represent a previously unknown category of usage, there is no reason to accommodate Dan’s stated needs or behaviors in the design. And that’s okay.

Some people will never realistically use your product. Don’t force fit them into your model just because you interviewed them. Do give them the incentive for participating.

6. Report the Results

The point of research is to influence decisions with evidence. While the output of the analysis is generally a summary report and one or more models (see Chapter 8), you need to be strategic.

The type of reporting you need to do depends on how decisions will be made based on the results. Within a small, tight-knit team, you can document more informally than at a larger organization, where you might need to influence executive decision-making. (And remember that no report will replace the necessary rapport-building and initial groundwork that you should have done at the very beginning.)

Given good data, a quick sketch of a persona or a photo of findings documented in sticky notes on a whiteboard in a visible location is far superior to a lengthy written report that no one reads. Always write up a brief, well-organized summary that includes goals, methods, insights, and recommendations. When you’re moving fast, it can be tempting to talk through your observations and move straight to designing, but think of your future self. You’ll be happy you took the trouble when you need to refer to the results later.

And Repeat

The only way to design systems that succeed for imperfect humans in the messy real world is to get out and talk to people in the messy real world. Once you start researching, you won’t feel right designing without it.