–( THREE )–

First Learn How to Talk to Yourself

Spend time in intentional self-reflection to enhance self-understanding and gain clarity on your values, beliefs, assumptions, biases, and judgments.

The ability to engage in inclusive conversations is a skill to be developed and honed. It is a necessary ingredient for cultural competence—a continuous learning process to gain knowledge and understanding of your own and other cultures, to be able to discern cultural patterns for more effective problem solving, decision-making, and conflict resolution. The journey to developing cultural competence includes three key skills that start with self-understanding after which you should focus on understanding your cultural “others.” Once you develop those two skills, you are ready to have inclusive conversations to effectively bridge across differences. Inclusive conversations require an advanced skill set and can happen only when the first two skills have been developed.

Talking to Yourself Fosters Self-Understanding

Self-understanding is essential to being able to dialogue across different dimensions of diversity. Understanding why you believe what you believe, where those beliefs come from, what has formed your worldview and created your particular mind-set is critical for effective inclusive conversations. The ability to critically reflect on interactions you have with others in your circle, those outside of your circle, and even strangers can help you to better understand your core beliefs and prepare for inclusive conversations. One of the best ways to better understand yourself is to spend time literally talking to yourself.

There is somewhat of a stigma associated with “talking to yourself.” Others may judge or criticize this practice. We may laugh and think that someone has a loose screw if we witness them talking to themselves out loud. However, we talk to ourselves all of the time, whether we realize it or not. You ask yourself questions about mundane day-to-day decisions as well as more important potentially life-altering decisions. Thinking is actually a form of talking to yourself. According to clinical psychologist Dr. Jessica Nicolosi, talking to ourselves out loud forces us to slow down our thoughts and process them differently because we engage the language centers of our brain. She says that when we talk to ourselves, we become more deliberate, which creates a slower process to think, feel, and act. In the same way we look to trusted companions for advice, Nicolosi says that we can talk to ourselves. This occurs when we’re experiencing a deep emotion, such as anger, fear, or other stressors. She says that it is typically some emotion that triggers us to speak out loud.1 Engaging in inclusive conversations can be stressful and triggering, and therefore self-talk is really important.

Intentionally spending time talking to yourself on a regular basis—both in quiet, thoughtful contemplation and out loud dissecting your daily thoughts, feelings, and actions—fosters self-understanding. Make it a new habit. Take self-talk to another level by keeping a journal and writing down your perspectives on your cross-cultural experiences and your interpretation of situations that you might hear or see in the media. In other words, have an inclusive conversation with yourself.

If you really listened to yourself, what are you thinking, what are you saying to yourself that you would not say out loud? What are you saying out loud that you really don’t believe but feel societal pressure to respond in a socially acceptable way? What drives your thoughts? How are your thoughts connected to your behaviors? What biases do you know that you have? All of these self-talk questions are key to self-understanding and enhance your ability to engage in inclusive conversations.

Focus on Self Is Not to Be Confused with Egocentrism or Individualism

The type of self-focus that I advocate should not be equated with egocentrism, a worldview that considers only one’s own cultural perspective and the inability to consider the perspective of other cultures.2 The self-reflection that is important for inclusive conversations is in service of learning how to more effectively engage with others. I am simply saying that the prerequisite for effectively engaging with others is deep self-knowledge and self-reflection.

Individualism is a value that has historically been associated with Western culture. It is defined as being motivated by personal rewards and benefits. The “I” is bigger than the “we.” In individualistic cultures, goals are established based on individual wants and desires. People see themselves as independent beings free to operate on their own. This worldview is contrasted to collectivist cultures, more associated with Eastern parts of the world, which prioritize the group or society over individuals. In these cultures, people view themselves as interdependent and are taught to do what is best for society as a whole rather than themselves as individuals. Based on their origins from collectivist cultures, African Americans, Asian Americans, Latinx, and Native Americans tend to be more collectivist than individualistic in the United States. For example, people with a collectivist mind-set might find exercises that focus on self more difficult because they cannot separate self from their connection to the larger society. By the same token, extreme individualism may impede our ability to see our connection to others and our collective responsibility for engaging at a societal level.

I posit that it is “both/and”—that is, we have to be able to see ourselves as individuals and also importantly as a part of the larger society comprised of systems that define our reality. The US individualistic idiom is “Pull yourself up by your own bootstraps.” This should be tempered with a more collectivist view that also considers those who have no boots and therefore perhaps need help from others. The idea of collective responsibility discussed in Chapter 2 may be an easier notion to digest for collectivist cultures.

Some sociologists argue that even as individuals our worldviews are shaped by our environments, experiences, and power structures. So there is really no independent or truly individualistic thinking, or as the saying goes, “There is no such thing as a view from nowhere.” The understanding of self is inextricably tied to our interpretations of history, power, politics, and other factors. Sociologist Stuart Hall says that the work of understanding self and identity is more about “deconstructing” than “discovery.”3

Learning to Practice Metacognition

Metacognition is an approach for deconstructing. It is the ability to think about and regulate one’s own thoughts. It is thinking about thinking and the ability through the process of thinking about thinking to change your thoughts.4 This concept is gaining popularity in how teachers train students to approach a task. It has been described as “knowing about knowing,” becoming “aware of one’s awareness” and the ability to engage in higher-order thinking skills. Metacognition refers to a level of thinking that involves active control over the process of thinking that is used in learning situations.

There are three stages of metacognitive thinking as it relates to inclusive conversations: planning, monitoring, and evaluation. During the planning phase, ask yourself:

![]() What will be required to engage in this inclusive conversation?

What will be required to engage in this inclusive conversation?

![]() Have I done anything like this in the past?

Have I done anything like this in the past?

![]() What do I already know about the topic of this conversation (e.g., race, sexual orientation, gender dynamics, and other dimensions of difference)?

What do I already know about the topic of this conversation (e.g., race, sexual orientation, gender dynamics, and other dimensions of difference)?

![]() What do I want as the outcome of this conversation?

What do I want as the outcome of this conversation?

![]() Is this a debate or a dialogue? Am I trying to win an argument or learn something new?

Is this a debate or a dialogue? Am I trying to win an argument or learn something new?

During the monitoring stage, which happens during the conversation, the key self-reflective questions include:

![]() Is the conversation leading toward the original goal?

Is the conversation leading toward the original goal?

![]() How well am I doing in practicing inclusion in this conversation? Am I keeping an open mind, or am I starting to be judgmental? Am I really listening to understand? Should I be asking more clarifying questions? Are we still dialoguing, or are we moving toward debate? Are there things being said that are triggering for me? Why?

How well am I doing in practicing inclusion in this conversation? Am I keeping an open mind, or am I starting to be judgmental? Am I really listening to understand? Should I be asking more clarifying questions? Are we still dialoguing, or are we moving toward debate? Are there things being said that are triggering for me? Why?

The third stage of metacognitive thinking is evaluation, after the conversation. Ask yourself:

![]() How did I do? Did I achieve the goal?

How did I do? Did I achieve the goal?

![]() What could I have done differently?

What could I have done differently?

![]() What biases did I notice surfacing in my thinking?

What biases did I notice surfacing in my thinking?

![]() What do I need to learn for these types of conversations to go better the next time?

What do I need to learn for these types of conversations to go better the next time?

![]() What made me say? How would I interpret the other person’s response? What in my life’s experiences made that a trigger for me? Why did I interpret that situation so differently from the other person?

What made me say? How would I interpret the other person’s response? What in my life’s experiences made that a trigger for me? Why did I interpret that situation so differently from the other person?

Some experts in metacognition have expanded the idea and embrace social metacognition, which includes the influence of culture and our self-concept on how we think.5

Self-Talk Helps Us to Manage Our Unconscious Bias

Unconscious bias is a very popular topic in the diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) arena today. I am often asked, “If my biases are unconscious, how do I know that I have them?” If we engage in metacognition, it is easier for us to bring what is unconscious to our consciousness. Our unconscious biases usually trigger a behavior or a thought that we verbalize. For example, “We always recruit from these schools because we get good talent.” Asking yourself why you said that and why you might be biased toward those schools can help you to be open to other options. Consider the statement: “I am okay with hiring underrepresented groups as long as they are qualified.” Asking yourself why you think an underrepresented group would not be qualified is metacognitive thinking. Learning to think metacognitively is a skill and habit that will enhance your capability for inclusive conversations.

The Role of Self-Concept in Effective Inclusive Conversations

Self-concept is influenced by social identities. A person’s social identity is their sense of who they are based on their group membership. Social psychologist Henri Tajfel proposed that the groups to which we belong (e.g., social class, family, race, ethnicity, nationality, profession, etc.) are an important source of pride and self-esteem.6 Research shows that people are motivated to have a positive social identity. When we feel connected to a social group (called social group identity), our self-esteem is higher and we feel safe and accepted.7 In contrast, when people feel excluded, rejected, or ignored by others, they experience hurt and pain and are likely to withdraw from the interaction.8

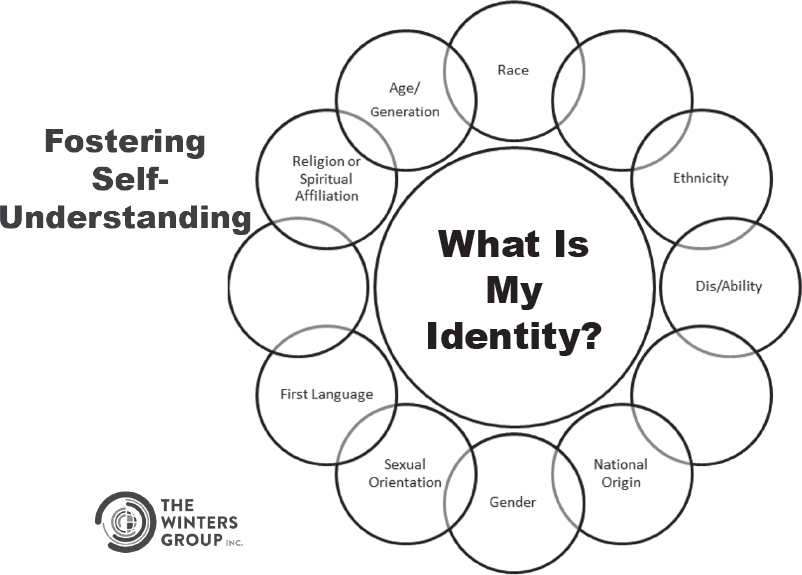

All of us belong to more than one social identity group, known as intersectionality. More and more employees are invited to bring their “whole” selves to work. The idea of “whole self” acknowledges that we have multiple identities that intersect and overlap. The term “intersectionality” was coined by Kimberle Crenshaw, professor at Columbia Law School and the University of California Los Angeles, to address the perpetual exclusion of Black women in feminist, antiracist discourse. Intersectionality recognizes that group identities (e.g. race, gender, sexuality, class, age) overlap and intersect in dynamic ways that shape an individual’s experience.9 Ask yourself, who am I and how do my multiple identities influence how I think about myself and others? The Winters Group uses an exercise that invites individuals to think about their intersecting identities (Figure 3.1). In which identities do you find yourself as a part of the dominant group or the subordinated group?

FIGURE 3.1 Fostering Self-Understanding

Source: Property of The Winters Group, Inc.

Dominant group membership might naturally lead to a more positive self-image, whereas membership in a subordinated group might engender feelings of inadequacy. Dominant groups are those with systemic power, privileges, and social status within a society. Conversely, subordinated groups are those that have been traditionally and historically oppressed, excluded, or disadvantaged in society. The concept of dominant and subordinated groups is explored more in Chapter 5.

Your position of dominance or subordination can influence your self-concept. Is your self-concept always positive? Do you have doubts about your capabilities that might play out as imposter syndrome or internalized oppression? Imposter syndrome is defined as feelings of inadequacy or incompetence despite demonstrated evidence of success.10 Behavorial scientists have found that women are more likely to experience the imposter syndrome than men.

Internalized oppression is a phenomenon usually associated with historically marginalized groups, where we begin to believe the negative stereotypes that are perpetuated by society. Self-reflecting on the extent to which these negative self-concepts are impeding your ability to engage fully and authentically in an inclusive conversation is key. Why do I feel inferior in this situation? What am I thinking about myself? How is it manifesting in my tone, my demeanor, my words? There may be a great deal of internal conflict as marginalized groups try to find their place in systems that unwittingly perpetuate inequities. Questions like “Is there something wrong with me?” might surface regularly.

This is why employee affinity groups are important in larger organizations to provide space for discussing common concerns. For those in dominant groups, questions might be different, such as “Am I even relevant anymore? It seems like everything is about gays or Blacks. What about the ordinary white man?” These concerns need to be addressed by individuals before engaging in inclusive conversations. For example, a white male might ask himself, “What evidence do I have that ‘everything’ is about gays and Blacks? Why is that my perception?” Practicing metacognitive thinking can support such self-inquiry and foster greater self-understanding.

Negative self-talk can impede progress in inclusive conversations. Focusing on a positive self-image is critical. Remind yourself of your accomplishments and your inherent worth. Try to tune out thoughts of inferiority or inadequacy and replace them with positive thoughts about who you are. Those from historically marginalized groups might ask themselves questions like these:

![]() Have you internalized the stereotype of angry Black woman or threatening Black man?

Have you internalized the stereotype of angry Black woman or threatening Black man?

![]() Is your self-concept limited by your physical abilities? Have you internalized negative self-talk that you are just somebody in a wheelchair who others pity?

Is your self-concept limited by your physical abilities? Have you internalized negative self-talk that you are just somebody in a wheelchair who others pity?

![]() Do you talk about yourself in negative ways because English is not your first language and to many you speak with an accent? Do you think that they think you are not as smart?

Do you talk about yourself in negative ways because English is not your first language and to many you speak with an accent? Do you think that they think you are not as smart?

![]() Do you think about yourself as irrelevant because you are a baby boomer still in the workplace and you feel out of touch with so many younger people taking leadership roles?

Do you think about yourself as irrelevant because you are a baby boomer still in the workplace and you feel out of touch with so many younger people taking leadership roles?

Developing a positive self-concept is a journey that starts early in one’s life. I recently saw a news clip of a three-year-old African American boy on his way to preschool. His parents had taught him to constantly remind himself “you are smart, you are blessed, and you can do anything.” The clip showed the boy chanting this over and over with a big smile on his face as he made his way to his first day of school. What is your positive self-talk chant?

Understand Your Styles and Your Preferences

There are many psychological tools and concepts that can support you in better understanding yourself and how you might approach inclusive conversations. The Myers-Briggs Type Indicator supports your understanding of your personality type. Are you extroverted or introverted? Judging or perceiving? An introvert might need more time to process, whereas an extrovert might process out loud in an inclusive conversation and be annoyed that the introvert is not doing the same. Emergenetics is a tool that is rooted in the concept that who you are today is the emergence of your behavior, genetic makeup, and life experiences.11 The Emergenetics Profile assesses you on four “Thinking Attributes” (conceptual, structural, social, and analytical) and three “Behavioral Attributes” (flexibility, assertiveness, and expressiveness). The extent to which we are skilled in emotional intelligence traits (emotional self-awareness, emotional self-management, awareness of the emotions of others feelings, and ability to effectively manage group emotions) influences the extent to which we can have effective cross-difference conversations.12 Emotional intelligence is well recognized today as a necessary skill for good leadership.

Another very useful self-awareness tool is the Intercultural Development Inventory, which measures our capability to effectively bridge across diversity dimensions.13 The theory says that either we see the world only from our own cultural frame, or we have a mind-set that allows us to understand the complexities of culture—a multicultural worldview—recognizing patterns in our own and other cultures to achieve mutually respectful outcomes. Most people who take the tool fall at minimization on the scale. Minimization is a place on the Intercultural Development Continuum where similarities are emphasized and prioritized and therefore differences might be missed. For example, someone at minimization might proudly declare that they are color-blind. They might say “people are just people and any differences really don’t matter.” I explain why this is problematic in the case scenario below, “I Don’t See Race.”

The Intercultural Conflict Style Inventory (ICS) is another tool to help us understand how we prefer to respond to conflict based on our culturally learned behaviors.14 Do you prefer to be direct or indirect in your communication? Emotionally expressive or controlled? Being aware of your conflict style and how it differs from another’s is an important consideration when engaging in inclusive conversations. The results of these types of tools can help in your self-understanding as well as understanding others. It is critical for inclusive conversations to understand your natural ways of being. For example, if your Emergenetics Profile reveals that you are a very conceptual person (big picture, visionary, imaginative, learns by experimenting) and you’re attempting a conversation with someone who is very structural (logical, likes guidelines, cautious of new ideas, learns by doing), it may take some adapting to each other’s styles before you are able to have a meaningful conversation.

CASE SCENARIO

(Emergenetics Styles)

Was It My Age?

You are a baby boomer leader. One of your millennial employees comes to you with what she thinks is a great idea. She shares the general concept with you. Your style is structural, while the millennial’s style is conceptual. You display confusion and give her feedback that you cannot envision how this idea can possibility be implemented in your organization. It is too far afield from anything that has ever been done. You tell her that in the future, before she brings such an idea, it would be helpful if she thinks it through more and considers the steps for implementation. The millennial leaves frustrated because she had hoped for a brainstorming session where the two of you would “imagine” the viability of the concept. She feels shut down and thinks that you are not taking her seriously because she is younger and newer to the organization.

The conversation might have gone better if both were aware of their different styles, acknowledged them upfront, and agreed on how the meeting should go to adapt to each of their preferences. The leader could have been more open and asked questions like, “Tell me a little more about the details?” The millennial employee might have been prepared to flesh out more of the details to account for her leader’s structural style.

CASE SCENARIO

(Intercultural Development Continuum)

“I Don’t See Race”

Consider two co-workers engaged in conversation, one white and the other Black. The white employee says to the Black employee, “I don’t really see your color. Your race makes no difference.” This sounds very much like a minimization statement. An inclusive conversation might sound something like this:

BLACK EMPLOYEE: While I understand that your intent is positive, the impact of such a statement is hurtful because it makes me feel that you are saying that you do not see me. It minimizes my racial identity, which is very important to me, and I want you to acknowledge it so that we can better discuss both our differences and similarities.

WHITE EMPLOYEE: Wow, it was not my intent to demean you. I thought it was a positive comment, and I would like to understand more about you and your perspectives.

This kind of conversation will be much more successful if they each have had some education on identities and perhaps have taken the Intercultural Development Inventory. Without having worked through some self-understanding, this could not have been an inclusive conversation.

At the conclusion of this conversation, the white employee should engage in some metacognitive self-talk, which might include questions like this:

![]() What do I need to learn for these types of conversations to go better the next time?

What do I need to learn for these types of conversations to go better the next time?

![]() What made me say that to my co-worker? How do I interpret my co-worker’s response?

What made me say that to my co-worker? How do I interpret my co-worker’s response?

![]() Am I open to change?

Am I open to change?

Self-understanding is a lifelong endeavor and one that many of us neglect. We cannot learn and grow if we do not engage in ongoing, intentional self-talk and self-reflection to understand who and why we are. Self-understanding means critically examining our thoughts, feelings, and behaviors and the cultural influences that have shaped them.

SUMMARY

![]() Talk to yourself out loud to slow down your thinking, feeling, and acting.

Talk to yourself out loud to slow down your thinking, feeling, and acting.

![]() Practice metacognition. Think about what you are thinking to manage your biases.

Practice metacognition. Think about what you are thinking to manage your biases.

![]() Know where you have power and use it to advance inclusion.

Know where you have power and use it to advance inclusion.

![]() Cultivate a positive self-concept and embrace your multiple intersecting identities.

Cultivate a positive self-concept and embrace your multiple intersecting identities.

![]() Learn about your natural styles, preferences, and worldviews as well as those of others.

Learn about your natural styles, preferences, and worldviews as well as those of others.

![]() Acknowledge different personalities, styles, preferences, and competencies at the beginning of conversations to honor your differences and increase the likelihood of achieving the goals of the inclusive conversation.

Acknowledge different personalities, styles, preferences, and competencies at the beginning of conversations to honor your differences and increase the likelihood of achieving the goals of the inclusive conversation.

Discussion/Reflection Questions

1. How much time do you spend in self-exploration, asking yourself why you believe what you believe, why you think what you think?

2. To what extent do you understand how your intersecting identities influence your worldview?

3. How much time do you spend considering how and why others might have a different worldview? How open are you to listening, understanding, and accepting other (even opposing) opinions?

4. What assessments have you taken that help you understand who you are? What assessments has your work team taken, and how do you use the information to engage in inclusive conversations?

5. How much time do you spend as a group discussing your similarities and differences and how they influence your team interactions? What can you do to enhance your understanding of your similarities and differences?