–( FIVE )–

Seek Equity and Decenter Power

Equity and power are inextricably entwined. Inclusive conversations must be equitable conversations and thus must consider power.

Equity is probably the most important condition for inclusive conversations. You really can’t talk about equity without talking about power. “Equity” is defined as the treatment of people according to what they need and deserve. Equity means everyone has access to the resources, opportunities, and power they need to reach their full potential. In the context of diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI), “power” is the ability to decide who has access to resources and the capacity to direct or influence the behavior of others, oneself, and/or the course of events. Power can be based on one’s position or one’s position, influence, and or privilege—defined as a system that maintains advantage and disadvantage based on social group memberships. Power thus operates, intentionally and unintentionally, on individual, institutional, and cultural levels.

The term “equity,” while certainly not new in the lexicon, is fairly new in the corporate diversity and inclusion space. “Equity” is a more elusive and controversial term than “diversity” and “inclusion.” There is still not a single definition for “diversity” and “inclusion” either, but equity seems to carry more contention than the other two. Perhaps we can think of diversity as the mix of differences in any particular setting to include (but not necessarily limited to) race, religion, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, nationality, age or generation, job function, and so on. Diversity is not limited to visible, physical differences. Inclusion is the act of understanding how those differences intersect and interact in group settings and ensuring that the differences are valued, respected, and understood. Inclusion is impossible without equity.

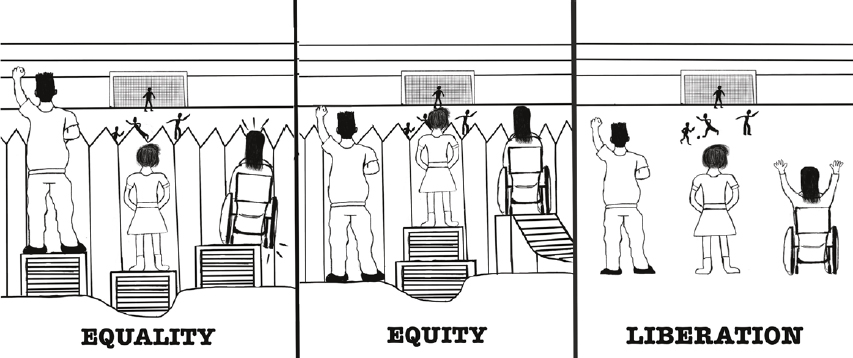

There is a popular image showing three children trying to view a baseball game over a fence (Figure 5.1). In the first picture, there is not level ground, and even though each child has the same size box, only one child can see the game. Here, each child is treated equally but not equitably. In the second picture, the children who were at a disadvantage are provided what they need to create equity. The third image shows the barrier (fence) completely removed and the ground level. This allows for liberation, defined as removing the barriers and inequities in the social systems that oppress or marginalize specific groups of people who share similar identities.

Even though “equity” has been more commonly used in the not-for-profit and social justice arenas before more recently gaining momentum in the corporate world, it remains an unclear term even in those areas with more experience using it. A 2016 article in the Stanford Social Innovation Review written for the philanthropic community asserts that “the term ‘equity’ is spreading like wildfire in some philanthropic circles. It is showing up more and more in organizations’ mission and values statements. It is making its way into the titles of conferences, plenary and breakout sessions, and meetings at the national, state, and local levels. Equity is one of those terms that everyone seems to understand at some visceral level, but few people share the same definition.”1

FIGURE 5.1 Equity versus Equality

Source: Created by The Winters Group, Inc., Krystle Nicholas artist.

If equity is the path to achieving inclusion and belonging, we have to start with equitable conversations. We cannot have equitable conversations if we cannot even agree on the definition of the word. The questions to ask about equity in preparing for inclusive conversations include: Are we assuming that everyone can see the ball game? What are the different needs that we should consider to ensure that the condition of equity is met? The conditions for an equitable conversation include:

1. A clear definition of equity.

2. Recognition of your power position in the conversation.

3. A deep understanding of where the person of lesser power is positioned and how that influences the impact and outcome of the conversation.

4. Exploration of what it would take to create an equitable environment for an inclusive conversation by giving agency (power to people to think and act to shape their experiences) to those in lesser power positions.

Power

Power differences can make it difficult to have an equitable conversation. Consider a conversation between a white male manager and an African American female direct report. The direct report has asked for the conversation because she feels that she is not being treated fairly. Two of her male colleagues have been promoted over her in the past two years, and she feels that her race and gender are the reasons she has been passed over. It is a male-dominated organization. The manager holds power as a male and as a leader. He should acknowledge his power in the situation and attempt to create a space where his direct report will have equal voice.

If you are the white male manager, engage in metacognitive thinking. Ask yourself: Why has this African American female direct report not been promoted? What skills is she lacking? Have I told her what they are? Do we have a plan in place for her to enhance those skills? If I cannot point to any deficiencies in her performance, do I have biases? If I was really honest with myself, what are some of those biases? Why is it that the entire leadership team is male? Do I think that she would not fit because in and out of work we have a kind of camaraderie that might make her and us uncomfortable? What do I know about how African American women fare at this company and in the work world in general? Are there systemic biases? Am I really going to work with her to help her achieve her goals? Explore research such as the study referenced in Chapter 1, conducted by McKinsey and LeanIn.org. The findings are that women of color are less likely to have managers who promote their work contributions and specifically that African American women do not get the same type of support to help them navigate organizational politics; also their managers are less likely to socialize with them outside of work.2 The result is that more often than not women of color are excluded from informal networks that are known to enhance career upward mobility.

If you are the African American woman, your thinking might include: What tangible contributions can I point to that exceeded expectations? Was I recognized for those achievements? What specific instances can I cite where my contributions were not acknowledged? Did my manager perceive the results to be above average? Are there deficiencies in my performance that I am overlooking? How likely is it that my manager will agree with my assessment? Is the “male” culture so entrenched that he has blind spots that may preclude him from seeing the difference in how I am treated? What are my choices if I don’t get the support that I need?

The meeting might start with dialogue like this:

DIRECT REPORT (AFRICAN AMERICAN WOMAN): As I mentioned when I requested this meeting, I want to discuss my career progress and better understand the steps I need to take so that I am given consideration when the next opportunity arises.

MANAGER (WHITE MALE): I am happy to talk with you, and I recognize that as your supervisor I have a lot to do with these decisions. By virtue of my position, power dynamics can stymie open and honest discussions. I want to acknowledge that and ask what you need in this discussion to feel that you are being listened to. What can I do to create a space where you feel that your perspective is just as important as mine?

DIRECT REPORT: This is not an easy conversation, and I appreciate you recognizing that. The conditions that will work for me are that you listen for understanding and not just to respond, and you acknowledge that societal discrimination and unconscious biases are real and may impact outcomes for people like me differently than for your identity, especially in the organizational culture that has primarily been run by men.

MANAGER: I promise to try to listen without judgment and to hear what you are saying. While it might be hard, I don’t want you to think about me as the boss but rather a trusted adviser who is listening to understand. With that, I will ask clarifying questions that might seem obvious to you but perhaps not so much to me. I would like you to assume that I have positive intent and am trying to enhance my understanding of your perspective. I also want you to feel comfortable pointing out the unintended impact that I may be having on you.

Being open, upfront about the fact that the power dynamics make equitable conversations difficult, sets up a greater likelihood that a brave space is being created.

The Complexities of Power

Power dynamics need to be considered for successful inclusive conversations as was attempted in the dialogue above. There is individual positional power and there is also systemic power defined earlier. In the scenario above both types of power are present. The boss has a role in the organization that affords him the power to make decisions about the career progression of those who report to him. He is also a member of an identity group (white male) that has historically enjoyed unearned privilege. The sociological concepts of dominant and subordinated groups help us understand systemic power dynamics.

Dominant groups are those with systemic power, privileges, and social status within a society. Conversely subordinated groups are those that have been traditionally/historically oppressed, excluded, or disadvantaged in society. Dominant groups are considered the norm and by default subordinated groups are considered “abnormal”; dominant groups make the rules, and all others are judged by their standards (Table 5.1).3 Dominance and subordination are not equivalent to majority and minority. Consider Apartheid in South Africa. Blacks were the numerical majority; even so, whites were the dominant group with the power.

It is important to note that we can hold power and privilege in one of our identity groups and be subordinated in another. For example, as a cisgender, heterosexual woman, I am part of a dominant group, whereas someone who identifies as a part of the LGBTQ community is a member of a subordinated group. There are still twenty-six states and three territories that do not have legislation banning employment discrimination against the LGBTQ community, and there is no federal legislation.4 Conversely, my identity as a Black woman makes me a part of a historically subordinated group.

TABLE 5.1 Dominant Groups and Subordinated Groups

Dominant Groups |

Subordinated Groups |

Considered the norm or default |

Seen as different, deviant from the norm |

Benefit from the status quo |

Expected to assimilate to status quo |

Typically unaware of group membership |

Aware of group membership |

Make the rules |

Must follow or adapt to rules |

Access to power, resources |

Barriers to access, resources |

Benefit of doubt |

Suspected |

Source: Based on Louise Diamond, “Dominant and Subordinate Group Membership,” Alliance for Peacebuilding. |

|

In one of The Winters Group experiential exercises to help participants understand power, we ask them to consider the identities that they shared in the “What Is My Identity” exercise described in detail in Chapter 3 and select those where they have a dominant position. Participants are asked to stand next to the chart of one of the identities. Others who share privilege in that same identity form a group and are asked to explore these questions:

1. How am I viewed as a member of this group?

2. How do I experience belonging?

3. When am I aware of my group membership?

4. How do I experience power as a member of this group?

5. What “rules” have been advantageous to me as a member of this group?

6. In what ways might my group be contributing to systemic inequity?

7. How can I use my social power to advance diversity, equity, and inclusion?

I recently participated in a poverty simulation that reminded me of the privileges I enjoy as a part of the middle class. As an example of how systems of power and privilege continue to disadvantage, the simulation highlights the systemic obstacles that people face on a day-to-day basis in their attempts to provide for their families and improve their economic situation. For instance, if the only way you can apply for a particular service is if you have transportation, and you rely on public transportation that is unreliable in your area, it may mean that by the time you arrive at the office to apply, it is closed. If you cannot afford childcare, you may have limited ability to follow up on job opportunities. The simulation demonstrates that no matter how hard one might try, systems may be unwittingly or intentionally set up to disadvantage you. The coronavirus pandemic magnified the differences between the “haves” and the “have-nots” that contributed to a disproportionate number of deaths of Black people in the United States.

Think about those identities where you are the dominant group—the group that is considered the norm—and answer the questions posed above. We cannot have inclusive conversations without considering power and privilege. The curious thing about power is that it may make us more prone to bias and stereotyping and less likely to be empathetic—one of the conditions for inclusive conversations that I describe in Chapter 8.

Research by Dr. Jeremy Hogeveen, Michael Inzlicht, and Sukhvinder Obhi goes as far as to say that power changes the way the brain responds to others.5 In their studies of brain wave changes the researchers found that powerful people are more apt to stereotype, less likely to listen to the perspectives of the less powerful, and are less empathetic. They concluded that this could explain the tendency for the powerful to neglect the powerless, and the tendency for the powerless to expend so much effort in understanding the powerful. Inclusive conversations have to acknowledge the inequities that may be inherent based on the dominant and subordinated positions of those pursuing the dialogue.

The example of the boss (a white man) and the direct report (an African American woman) provides guidance for one-to-one conversation where power needs to be acknowledged. If it is a group dialogue, consider these questions in metacognitive self-talk: Am I aware of my power? Who is in the power position in the conversation? If it is me, how will I share my power? Am I stereotyping? Am I able to be empathetic? How do I acknowledge my power in an inclusive way? If I am not in the power position, questions might include: Do I feel that my voice will be heard? What are my triggers that might impact my ability to engage in this conversation? What biases do I have about those who are in the dominant/power position? Here are some possible ways to equalize power in a team conversation:

![]() Acknowledge and discuss the concepts of dominant and subordinated group dynamics before the conversation so that participants are aware of these realities.

Acknowledge and discuss the concepts of dominant and subordinated group dynamics before the conversation so that participants are aware of these realities.

![]() Be explicit that the intent is to create a space for equitable dialogue.

Be explicit that the intent is to create a space for equitable dialogue.

![]() Develop equitable conditions by asking each person in the group what needs to happen for them to feel heard during this conversation.

Develop equitable conditions by asking each person in the group what needs to happen for them to feel heard during this conversation.

![]() Allow the person/people in the subordinated position to talk first.

Allow the person/people in the subordinated position to talk first.

![]() Give those in a subordinated position more air-time.

Give those in a subordinated position more air-time.

![]() Call out perspectives that uphold dominant societal norms and narratives, as well as those that minimize or dismiss subordinated group perspectives.

Call out perspectives that uphold dominant societal norms and narratives, as well as those that minimize or dismiss subordinated group perspectives.

Practice multipartiality, which is defined as an empathetic openness and the ability to integrate opposing perspectives and models in dialogue. Strategies to attain multipartiality in inclusive conversations include:

![]() Identify the goal: “The goal of this conversation is to . . .”

Identify the goal: “The goal of this conversation is to . . .”

![]() Combat binaries using “both/and” instead of narratives or arguments that suggest “either/or.”

Combat binaries using “both/and” instead of narratives or arguments that suggest “either/or.”

![]() Call out the gaps by asking, “Who or what community is not a part of this conversation? Why?” For example, if you are on a committee that is discussing new policies for dress codes in school, are parents a part of the conversation? If your organization is conducting an engagement survey, do you include the voices of the DEI practitioners as to what questions to include on the organization’s inclusive practices?

Call out the gaps by asking, “Who or what community is not a part of this conversation? Why?” For example, if you are on a committee that is discussing new policies for dress codes in school, are parents a part of the conversation? If your organization is conducting an engagement survey, do you include the voices of the DEI practitioners as to what questions to include on the organization’s inclusive practices?

![]() Redirect from dominant narratives by asking, “Does anyone have a different experience from those shared?” Sometimes those from historically excluded groups do not offer their perspective when it is obviously different from that of the dominant group that holds the power.

Redirect from dominant narratives by asking, “Does anyone have a different experience from those shared?” Sometimes those from historically excluded groups do not offer their perspective when it is obviously different from that of the dominant group that holds the power.

![]() Be prepared to share unrepresented experiences using narrative, video, guest speakers, and so on.

Be prepared to share unrepresented experiences using narrative, video, guest speakers, and so on.

![]() Clarify what is at stake: “If we do not consider the experiences of [underrepresented group], then . . .”

Clarify what is at stake: “If we do not consider the experiences of [underrepresented group], then . . .”

Power can either thwart or enhance our ability to have inclusive conversations. It depends on how we use it. If we acknowledge it and strive for equity, it is clearly an enhancer. If we are oblivious to it, or wield it in ways to continue to subordinate others, power obstructs any attempts to engage in inclusive conversations.

SUMMARY

![]() Inclusive conversations, by definition, must be equitable conversations.

Inclusive conversations, by definition, must be equitable conversations.

![]() Equity is giving people what they need and deserve. Equality is giving everyone the same regardless of need.

Equity is giving people what they need and deserve. Equality is giving everyone the same regardless of need.

![]() We cannot have equitable conversations without naming the power dynamics.

We cannot have equitable conversations without naming the power dynamics.

![]() Create brave spaces to discuss equity and power.

Create brave spaces to discuss equity and power.

![]() Dominant groups are those with systemic power, privileges, and social status within a society. Conversely subordinated groups are those that have been traditionally/historically oppressed, excluded, or disadvantaged in society.

Dominant groups are those with systemic power, privileges, and social status within a society. Conversely subordinated groups are those that have been traditionally/historically oppressed, excluded, or disadvantaged in society.

![]() The power afforded to dominant groups is not necessarily earned or wanted. It is not their fault that they have it. It is, however, crucial to acknowledge it and use it to dismantle the inequitable systems.

The power afforded to dominant groups is not necessarily earned or wanted. It is not their fault that they have it. It is, however, crucial to acknowledge it and use it to dismantle the inequitable systems.

Discussion/Reflection Questions

1. In what ways do you distinguish equality and equity? What systems in your organization are based on an equality-versus-equity framework?

2. What are some ways to move from equity to liberation?

3. Where is your power? Is it positional? Dominant group?

4. On a day-to-day basis, how do you include historically subordinated voices?

5. How do you use your power to dismantle inequitable systems?