9

Organizational Solutions for Improving Culture

Culture eats strategy for breakfast.

PETER DRUCKER1

A culture committed to passion for patient care and professional fulfillment is critical to developing and sustaining organizational resilience. However, culture creates burnout when it espouses professional fulfillment but the culture “in action” is different, as Chris Argyris notes.2 When the “words on the walls” aren’t matched by the “happenings in the halls,”3 burnout is inevitable. Culture is not just what people do in an organization, it is also what they say they do, as well as how they think, particularly how they think about change, improvement, and innovation. Few things further widen the gap between job stressors and the resilience required to deal with them than leaders who espouse one culture but embody another. Leaders who proclaim they have a great culture but have burnout rates of nearly 50 percent are disconnected from the reality of how burnout occurs. As Steve Narang, the president of the Inova Fairfax Medical Campus of Inova Health System, notes, “Culture comes straight from the airway of the organization.”4 Physicians and nurses all learn the “ABCs” of resuscitation, always starting with A, the airway. Narang is precise in noting that culture constitutes the first and most important part of “resuscitating” organizations suffering from burnout. Similarly, Ed Schein famously noted that, “Leadership and culture are two sides of the same coin.”5

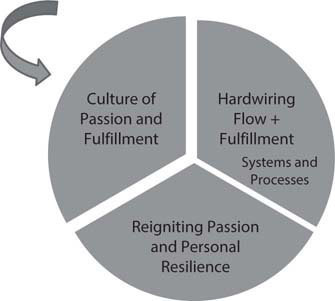

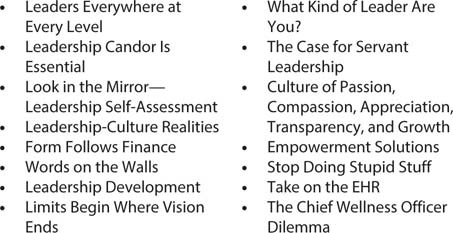

Fortunately, the gap between job stressors and the resilience they require can be avoided because there is a suite of solutions designed to create a culture of passion and personal and professional fulfillment in healthcare (Figure 9-1). These solutions cut across the Maslach domains, as shown in Figure 9-2.

Figure 9-1: Solutions to Create a Culture of Passion and Personal Resilience

Figure 9-2: Solutions to Create a Culture of Passion and Personal Resilience by Maslach Domain

Leaders Everywhere at Every Level

In creating culture, “leadership” does not mean just senior leaders or department directors. Every time healthcare team members show up to work, they are responsible for leading their part of healthcare. Every doctor, every nurse, every lab technician, every imaging specialist, and every person in environmental services (EVS) leads themselves and those with whom they interact during the course of their work in creating a culture that day, that evening, that night. They create “happenings in the halls” that collectively define the organization and its culture.

In healthcare, leadership is for everyone because everyone leads.

Lead yourself, lead your team.

Leaders at all levels are performance athletes who need performance and recovery.

Invest in yourself, invest in your team.

The work begins within.

Leadership Candor Is Essential

While leadership at all levels is essential to battling burnout, in the arena of culture, leadership is the issue.6 This requires an unprecedented level of candor, precisely because it takes a tremendous amount of intellectual honesty to admit that our current culture is what created—or at the very least allowed—burnout to occur. To those who say, “We have a culture of passion and fulfillment,” the logical question is, “Then why are half your team members suffering from burnout? If they trusted your culture, they wouldn’t be burned out.”

The role that leadership has inadvertently played in burnout’s creation requires honesty and candor. The importance of candor is not to create a sense of guilt about how we got here, but to create hope in changing the culture for the future. It is important to reiterate that part of measurement is to assess, usually in a free text format, what the team members feel are the major issues regarding culture and organizational adaptive capacity. Ed Schein understood the importance of both candor and an iterative approach to leadership’s role in culture: “The ability to perceive the limitations of one’s own culture and to develop the culture adaptively is the essence and ultimate challenge of leadership.”5

The courage to embrace input on the culture and its impact, including its unintended consequences, is fundamentally a commitment to hearing the following:

• the “voice of the patient” regarding what reality is for them7

• the “voice of the provider” regarding whether the culture results in burnout, to what extent, and what the specific reasons are

There are two important dynamic tensions regarding culture and burnout. To Narang’s excellent point, culture is a primary function of leadership and its ability to frame the context in which healthcare work is done, as well as ensure there is sufficient organizational resilience or adaptive capacity to do so. At the same time, that adaptive capacity arises from the ability of the culture (as embodied by its leaders) to show iterative resiliency.

The second dynamic tension is that nothing can be purely culture since it can never be defined in the abstract or in isolation—it can only be discovered in the actions of the organization and its leaders.7–9 Of necessity, changing culture has significant implications for both the hardwiring of flow and fulfillment and personal resiliency.10

Look in the Mirror: Leadership Self-Assessment

The key issue is how leaders at all levels embody the stated culture through their actions and decisions. That starts by taking a long, reflective look in the mirror. These questions are important to consider:

• Does your healthcare system invest in leadership development?

• Is leadership development focused on helping the individual or on how the individual can improve results for the organization?

• Do you promote those who promote personal and professional fulfillment through the leadership culture?

• Whose actions embody the positive aspects of your culture?

• Who is doing innovative and unexpected things to advance a culture of passion and fulfillment?

• What risks were they willing to take to be innovative?

• Is there a culture of appreciation or underappreciation in the system?

• Is there a deep and abiding sense of community and transparency?

• Does the chief wellness officer report to the CEO or the chief operating officer (COO)? If not, why not?

• Is your culture one where systems and processes change as a result of identifying burnout and its sequelae?

Now go back and give specific examples that support your answers. The self-assessment gets a lot harder when we are required to do this. I was a theology major when I was in college. At the end of my senior year, we had four hours to complete our written final exam, which comprised an envelope with questions and several blue notebooks in which to write. Fortunately, the exam was on an honor system, so you could open the envelope anytime and anywhere you wanted, as long as you completed it in four hours, based solely on your thoughts and without consulting notes, textbooks, or other people. I opened my envelope and the question read, “Discuss the Old and New Testaments. Give examples.” I thought for a couple of moments and wrote, “The Old Testament says, ‘It’s the Law.’ The New Testament says, ‘It’s a little more complicated than that …’” I would have been done, except for that pesky, “Give examples.” That took a lot longer. And the “leadership look in the mirror” will take a lot longer when it comes to giving examples.

Form Follows Function, Form Follows Finance

While many people are familiar with the saying “form follows function,” most are perhaps less so with the phrase “form follows finance.” Both are applicable to the inextricable relationship of leadership and culture. To an increasing degree, leaders are also guided by the financial aspects—how much and for what each area is reimbursed. For a typical department in a large hospital or healthcare systems, there are vice chairs or associate medical directors for the following:

• quality

• patient safety

• patient experience

• performance improvement/flow

Is there a vice chair or associate director for wellness and resiliency? If not, why not? The “business case for battling burnout” is clear and shows the return on investment (ROI) for investing in such a position and giving that person an appropriate budget and authority to make changes to the system, which is producing precisely the results it is designed to. Another way of thinking about this is the adage often used by my colleagues Liz Jazwiec and Craig Deao, “What gets rewarded gets repeated.”11

Under the assumption that a leadership position is some sort of reward, create a position of vice chair or associate medical or nursing director for wellness and resilience with the appropriate protected time, compensation, and authority. The broader dilemma of the chief wellness officer is discussed later in this chapter.

Words on the Walls, Happenings in the Halls

Leaders must be fanatical about looking for examples where the “words on the walls” are not matched by the “happenings in the halls.” Use the process described in Chapter 6 to close this gap.

Leadership Development to Battle Burnout

The single most important concept in creating a culture of passion and fulfillment is that every team member at every level in every healthcare organization is a leader. Each of us is responsible for leading ourselves and our teams through our words, thoughts, and actions. Hospital medicine physicians are leaders creating a culture for that day for the team members and patients for which they are responsible. Nurses, even if they are not the charge nurse, use leadership principles to manage their patients. The essential services team leads the way in providing imaging, laboratory, registration, and environmental services, and they collectively create a culture through these actions. Make sure your teams at all levels understand this and that your organization invests in leadership skills for everyone, not just those with formal titles.

If every team member is a leader, every team member requires leadership training to battle burnout, first within themselves, then within the team. Across healthcare, training is essential but too often neglected. As Sir Richard Branson, founder of Virgin Airways, said, “Train people well enough they can leave. Treat them well enough so they don’t want to.”12 Coaching is an important part of leadership training, as John Wooden, UCLA men’s basketball coach and winner of ten national championships, noted, “I was never much of a game coach, but I was a pretty good practice coach.”13

All healthcare systems have some level of leadership development training, but few have a specific focus on educating leaders on the definition, effective treatment, and prevention of burnout.14

DEFINING BURNOUT

Effective leadership for burnout should start with a common definition, which should be known throughout the organization. This simple step is too often overlooked. As you may recall, here is our definition:

Burnout is a mismatch between job stressors and the adaptive capacity or resiliency required to deal with those stressors, which results in three cardinal symptoms:

1. Emotional exhaustion

2. Cynicism

3. Loss of a sense of meaning in work

Ensure the definition is universally known and understood and that it is a part of leadership development training and team meetings.

JOB STRESSORS

Leaders should be “data and information mavens,” constantly seeking to understand the job stressors for each unit for which they are responsible; the variable stressors for nurses, doctors, and essential services members; and how the teams’ efforts to battle burnout are faring “down in the trenches.” While Chapters 17–19 discuss the tools for battling burnout in detail, one specific tool can be extremely helpful in identifying and ameliorating job stresses: the “love, hate, tolerate tool.” In team meetings, the concept should be introduced, and team members should be encouraged to reflect on their answers, both individually at first and then in subsequent team meetings (Figure 9-3).

Figure 9-3: The “Love, Hate, Tolerate” Tool

Asking people what they love and maximizing it is a step toward helping people reclarify the passion that brought them to healthcare.

To be sure, Dr. Knight wasn’t able to completely eliminate the intrusion of the EHR, but she was able to decrease it and her burnout symptoms improved dramatically. (I will discuss the use of scribes and virtual scribes in Chapter 11.)

Leadership exists at every level, in every person, with every patient in healthcare. There are no unimportant members of the team. As a result of Earl’s report to the leadership team, the culture of the organization changed, since everyone began to thank the EVS team members whenever and wherever they saw them. Disciplined leader rounding can also be an effective tool to learn job stressors and gather thoughts on how to reduce or eliminate them. Regardless of what methods are used, leaders at every level of healthcare should actively seek to learn and more fully understand the job stressors their team members face and how they are changing over time.

ADAPTIVE CAPACITY OR RESILIENCE

Increasing organizational adaptive capacity and resilience combines elements of culture and the hardwiring of flow and fulfillment by changing the systems and processes that are needed.6,10 Leaders should be taught the tools needed to provide their teams with those same tools, including stakeholder analysis,15 boundary management,16 communication skills,17 and the tools of teams and teamwork.18–19 Learning to provide a sense of balance between organizational and personal resiliency is also important. Leader rounding and the “love, hate, tolerate” exercise are both helpful here as well.

CASE STUDY

Sharyn Knight is a family medicine physician who is considered by her patients and her peers to be among the kindest, most committed physicians in the healthcare system, but she admits that the stressors she faces are challenging. When asked to do the “love, hate, tolerate” exercise, her eyes flooded with tears as she said, “I love sitting and talking with my patients and their families, getting to explore how best I can help them through their lives.” What she hates is the “distraction and intrusion of the electronic health record [EHR],” which she said is “like this monster of an obstacle between my patients and me.” As she worked with her leader on these issues, maximizing her “love” and eliminating her “hate” led to her experimenting with using a medical scribe to interface with the computer/EHR, allowing her to focus on interacting with her patients.

CASE STUDY

Earl Thomas is the director of EVS for a large hospital. He decided to do the “love, hate, tolerate” exercise with his team, which required translating it into several different languages, because of the cultural diversity of his staff. The CEO was impressed that Earl had done this and asked him to present his results to the entire leadership team at their monthly meeting.

A naturally shy yet very articulate man, Earl started by saying how humbled and honored he was to speak to the group and then told the assembled crowd the results of the exercise.

“What our team loves is the chance to participate in some way, no matter how small, in helping our patients get well and back to their families. That and the occasional smile and kind word the doctors and nurses give them make it all worth it.

“What our team hates is when people walk past them in the hallways and don’t even acknowledge them with a nod, a smile, or even the rare ‘thank you.’ To be ignored is what they hate.

“The rest they just tolerate as the price they pay in doing the job.”

If I told you there wasn’t a dry eye in the house, I wouldn’t be exaggerating. Some of the nurses and even a few physicians were sobbing, since they had never realized they were sometimes walking past members of the EVS team without even acknowledging them.

RETURNING FROM BURNOUT

Despite leaders’ best efforts to prevent burnout, there are times when job stressors (and the changes creating them) will exceed resiliency’s ability to counteract them, resulting in exhaustion, cynicism, and loss of meaning at work. Leaders must be masters at helping their team members in their “journey back from burnout.” The first step in that journey is creating a culture that understands how and why burnout occurs and in which compassion is a constant. As I’ve discussed, there is always some element of shame for those who suffer from burnout, so compassion and understanding are requisite to guide the journey back to reconnecting their passion.20–21 Coaching and mentoring not only should be core values of the culture but are disciplined skills that must be taught to all leaders at all levels of the organization.22–23

REDESIGNING PERFORMANCE ASSESSMENTS

Too many hospitals and healthcare institutions have performance assessment processes that reek of hierarchical, authoritarian interactions and too little chance to compare the demands of the job with the resources needed to complete the tasks. As Peter Block,24 Tom Peters,25 and Peter Drucker26 have noted, the sessions often have an almost neocolonial feel, as professionals feel they are fundamentally being told the following:

• “Here are your deficiencies.”

• “Here are the data supporting your deficiencies (which you had no voice in generating).”

• “Here’s the timeline for reassessing your deficient performance.”

• “Fix it!”

• “How do feel about your deficiencies?”

• “Oh, by the way, I basically own you.”

A far more productive approach is to use these assessments as a means of coaching and mentoring team members, including by addressing where they stand on burnout (both objectively and subjectively). This would involve addressing both ways individuals can augment their capacity to deal with job stressors and ways the job itself can be changed to make it less stressful and more manageable. (What a revolutionary concept—a performance assessment that takes into consideration both how the person is performing and how the job is performing for the person.)27

ITERATIVE APPROACH

As we navigate the “perpetual whitewater of change,”17 it becomes increasingly apparent that the only constant is change. Leaders should have a change management strategy, of which there are numerous examples, such as those in the work of Kurt Lewin,28 Abraham Maslow,29 William Bridges,30 Elizabeth Kubler-Ross,31 and John Kotter.32 It matters less what change model is used, but it matters greatly if leaders have not thought out which model will guide them and their teams. Not surprisingly, to help others with adaptive capacity requires an ongoing, iterative approach to dealing with changing job stressors.

LEADING FROM THE FRONT

Leadership development programs should always stress the critical importance of “leading from the front.” Leaders who share and understand the travails of those they lead are universally more successful than those who fail to understand this insight.33–34 There is a rich history of this concept, particularly in the military, from the Greeks and Romans to Grant and Lee to numerous World War II generals, including George Patton, Bernard Montgomery, Terry Allen, Norman Cota, Teddy Roosevelt Jr., “Brute” Krulak, and Charles de Gaulle.35–37 (Patton always either walked or rode in an open staff car on his way to the front with the Third Army in France but always flew back to headquarters by plane or in an enclosed car, so he would not be seen by his men as “retreating.”)38

For healthcare leaders and managers, this means spending as much time as possible, particularly in times of change, on the front lines with physicians and nurses providing care. Ask open-ended questions like these:

• “What could I do to make your jobs easier and your patients’ lives better?”

• “Whom should I compliment today?”

• “Which patients should I listen to today?”

• “What job stressors are particularly meaningful today? What can I do to help?”

While leaders may not always be able to end job stressors immediately, they can put them in perspective and seek to increase adaptive capacity.

Limits Begin Where Vision Ends: Using Vision to Create Culture

Successful leadership does not occur without developing and communicating a clear vision of what constitutes success for the team and their patients. On May 6, 1954, Roger Bannister, then a medical student at Oxford University studying exercise physiology, ran humankind’s first sub-4-minute mile, covering the distance in 3 minutes, 59.4 seconds. In a way that can scarcely be imagined over 65 years later, this event truly stunned the world, despite the fact that Bannister and two other runners, American Wes Santee and Australian John Landy, were each working furiously to do so.39 Many of the most sophisticated medical experts of the time had said that the feat was simply impossible—the human body was incapable of attaining it, and a man would die in the attempt.40 The accomplishment was treated, as well it should have been, as a triumph not just of athleticism but of the human spirit. (When Bannister finished his earth-shaking feat, he thanked three groups of people. The first were his pacers and training companions Chris Chataway and Chris Brasher. The second was his mother. The third was a man named William Morris, the groundskeeper at Iffley Road Track, who Bannister felt had played a critical role in having the track in pristine condition.40 There are no unimportant people.)

However, 27 months after May 6, 1954, 10 runners had run sub-four-minute miles. In fact, one year and two weeks later, three men, in the same day, in the same race, did so. Something had happened that had never before happened in human history and that was felt by many to be physiologically unattainable—and yet, once the vision became a reality, it almost became commonplace. In fact, by 2012, 1,000 men had run a sub-four-minute mile. This is precisely what is meant by “limits begin where vision ends.”41

If there is a shared vision expanding the limits of the organization, one of the most fertile areas to explore is the experience of other leaders committed to creating a culture of passion and fulfillment. Make sure you are regularly reaching out to them to share experiences in battling burnout. Bannister, Santee, and Landy were competitors, not collaborators. They were not sharing the lessons learned in their quest, which might have increased the pace of progress for all of them. And don’t forget that one year and two weeks after Bannister ran his race, three men broke the four-minute barrier in the same race. It is a testament to the power of people to pull others along with them to achieve seemingly impossible things together. Use your colleagues to help fuel your quest.

The Case for Servant Leadership

The pioneer of servant leadership was Robert Greenleaf, who is among the most influential people in the field of leadership. Simply stated, servant leadership focuses not on the leaders and their needs but rather on those being served and whether they grow and develop in the course of being served.

In a penetrating 1969 essay that dramatically changed the way leaders were viewed, Greenleaf wrote,

A fresh critical look is being taken at the issues of power and authority, and people are beginning to learn, however haltingly, to relate to one another in less coercive and more creatively supporting ways. A new moral principle is emerging, which holds that the only authority deserving one’s allegiance is that which is freely and knowingly granted by the led to the leader in response to, and in proportion to, the clearly evident servant stature of the leader. Those who choose to follow this principle will not casually accept the authority of existing institutions. Rather, they will freely respond only to individuals who were chosen as leaders because they were proven and trusted as servants.42

Greenleaf recognized that such a concept would not be welcomed in the existing corridors of power, where too few view themselves as servants and too many have viewed leadership as exerting power and authority over those who are led. The servant leader is always a servant first, then a leader. These are understandably extreme ends of the leadership spectrum, between which, as Greenleaf noted, “are shadings and blends that are part of the infinite variety of human nature.”42

Servant leadership presents a dynamic tension between a call for service and the legitimate need to exercise accountability. Leaders and managers are called on, by the very nature of their duties, not only to lead but also to hold those led to accountable and measurable results. This trend in healthcare is accelerating, not declining. Leaders and managers are accountable for producing results as a part of their contract and their performance plans. In this environment, how can one emphasize servant leadership?

Consider the following two quotes, which highlight this dynamic tension between servant leadership and accountability. The first answers the question, “What is the best test of the servant leader?”

Do those served grow as persons? Do they, while being served, become, healthier, wiser, freer, more autonomous, more likely themselves to become servants? And, what is the effect on the least privileged in society?42

Greenleaf’s focus is on those who are being served, as opposed to those who are leading, and our ability to expand their capabilities. While Greenleaf was not speaking specifically of healthcare leaders, one can’t help but be impressed at the applicability of what he says to what healthcare leaders do daily, which is serve others, help expand their capabilities, and consider “the effect on the least privileged in society.” Contrast this with these words, which speak to the use of power and accountability among servant leaders:

I cannot conceive why anyone would want to be in a position of leadership anywhere unless one is comfortable with getting and using power. The wear and tear on the individual who leads is too great, and nothing, in my judgment, but the satisfaction of using power would compensate for the personal investment.42

While there are many descriptions of servant leadership, none is better than that of Frances Hesselbein, former CEO of the Girl Scouts of America, Presidential Medal of Freedom winner, and one of the great leaders of our time: “Leadership is a matter of how to be, not what to do.”43

Recall that teams are not groups of people who work together—they are groups of people who trust each other. So the core competency of servant leaders is the ability to engender and cultivate not just trust in themselves but also the team members’ mutual trust of each other. As healthcare leaders and managers, we must be able to create teams capable of serving first but serving consistently and accountably as well. As Spinoza said, “Excellence is what we strive for, but consistency is what we demand.”44

The dynamic tension that Greenleaf identifies between servant leaders and their use of power is apparent when we consider that all leaders seek to provide medical and service quality in each encounter by every team member, but reaching that end requires “getting and using power” to ensure accountability by teaching and developing the disciplines needed to achieve those scores through intrinsic motivation. Greenleaf notes, “Every achievement starts with a goal—but not just any goal and not just anybody saying it. The one who states the goal must enlist trust, especially if it is a high-risk or visionary goal, because those who follow are asked to accept the risking with the leader.”42 Leaders who wish to embrace their role in creating culture must have the ability to tie the passion and dedication of the team to the goals. Greenleaf says it best: “Not much happens without a dream. And for something great to happen, there must be a great dream. Behind every great achievement is a dreamer of great dreams.”42

My advice is simple: Dream great dreams and create a great culture.

Culture of Passion, Compassion, Appreciation, Transparency, and Personal and Professional Growth

Passion is the key to both professional and personal fulfillment, so a culture of passion is essential to create the passion reconnect needed to battle burnout. The values of passion for the job; compassion and appreciation for ourselves, our patients, and our team members; transparency of results communicated in a timely manner; and a commitment to personal and professional growth and development are all essential to a successful healthcare organization. This includes a commitment to the following:

• ourselves

• our patients

• our team

A COMMITMENT TO OURSELVES

It might seem counterintuitive to begin with our commitment to ourselves to create a culture through daily action. But unless we can express our own passion and have compassion and appreciation for ourselves, we can’t begin to truly have it for others.

Not to be overly critical, but the nurse’s response inadvertently deflects the praise the trauma surgeon is sending her way, possibly because of a lack of ability to accept a compliment. “Thank you. I thought it went well, too. I’ll tell the team you said that,” might be a bit better in treating herself to the deserved praise sent her way. This might seem a fine point, but look for this on leader rounds.

Unless we can be compassionate to ourselves, unless we can genuinely forgive ourselves, we have little hope of forgiving others. And forgiving others is a part of our daily work. Simply stated, we will never be able to treat our patients and our teammates well if we can’t find it in our hearts to treat ourselves well.44

CASE STUDY

Sara Scott is the chief of trauma surgery, and she is called to the emergency department trauma resuscitation area for a “code blue,” the highest level acuity for a trauma patient. The resuscitation is long, complex, and difficult, but the patient is finally stabilized enough to be taken to the operating room.

As she prepares to head to the operating room, Dr. Scott turns to the charge nurse, who ran the nursing side of the team, and says, “Great job. That was a tough one, but you handled it superbly.” The nurse says, “Thanks, but it really wasn’t anything.”

A COMMITMENT TO OUR PATIENTS

Passion for our patients is obviously what brought us to healthcare and sustains us in difficult times. (And these days, they all seem to be difficult times.) I discussed this in detail in Chapter 1, but these are key parts of a culture of passion, compassion, appreciation, and transparency regarding the patient:

• making the patient part of the team

• moving from “What’s the matter with you?” to “What matters to you?”

• patients as participants in their care, not just recipients of their care

• “nothing about you without you”

With every patient, we should encourage ourselves and our team to think, “How does what I’m doing reflect passion, compassion, and appreciation?”

A COMMITMENT TO OUR TEAM MEMBERS

With extremely rare exceptions, all of healthcare is a team sport. The care we provide is always provided with the help of others, without whom we couldn’t serve our patients. This accentuates “the seams of the teams,” which are the many handoffs and transitions that occur during care. The way we treat each other is a strong signal not just to the team members but also to the patients, families, and others who observe our interactions. I will discuss the concept of “leading up/managing up” in Chapter 10, but this is the skill of making those with whom we work start their interaction in a positive fashion, especially in the course of transitions of care from one person to another or one service to another.

A culture of appreciation always begins with personal praise at the patients’ bedside but extends into how we treat each other and some of the small symbols and gestures in our interactions. Henry Clay said, “Courtesies of a small and trivial nature are the ones which strike deepest in the grateful and appreciating heart.”45

One simple way in which appreciation can be expressed is to heed the age-old wisdom that breaking bread builds bonds of fellowship. Many healthcare systems have leveraged this by providing meals to facilitate these communications. Brigham Health has implemented the “Brigham-to-Table” initiative, which provides meals three times per week to its patient care units, in an attempt to bring their teams together for meals and conversation. One colleague described his system’s efforts to show appreciation through paid communal meals by saying, “We went from ‘Breaking Bad’ to ‘Breaking Bread.’”46

EXAMPLES OF “LEADING UP”

Hospital medicine physician to patient: “John is your nurse, and he’s one of the best we have.”

Nurse to inpatient: “Your hospitalist has requested a consult with the cardiologist, Dr. O’Brien. He’s not only a great doctor but a great person as well. I know you will like him.”

All of this requires a fundamental value of integrity, which has many definitions, and about which much has been written. Cheryl Battle at Inova Health System defines it as follows: “Integrity is what you do when there is no one else around.”47 I can’t improve on that and I know no one who can.

Empowerment Solutions

Empowerment is one of the most overused and least understood terms in healthcare. Detailed service and healthcare research indicates that no service leader, within healthcare or other industries, has ever succeeded without a deep culture of empowerment. Indeed, world-class organizations such as Mayo Clinic consider it a central tenet of their culture.48 Empowerment means that those providing the service have the ability to change or improve the service or processes if it better meets the patients’ needs or expectations to improve patient experience.17 Easily said, but much harder to deliver in a practical fashion.

At a large, prestigious healthcare system with a reputation for having empowered programs, I posed this question: “Are you empowered?” The silence, frankly, was a bit disquieting, until a small voice from the back of the auditorium said, “They tell us we are.” If the team is told they are empowered but the reality of that empowerment isn’t clear, it’s time to start over.

POINT-OF-IMPACT INTERVENTION

The best empowerment tool is point-of-impact intervention, which is a combination of the concepts of empowerment and negotiation. It begins with the insight that in patients who registered a complaint about their care, when their caregivers were asked whether they had any notion that the patient was unhappy at the time, 92 percent said yes. In other words, the majority of the time, when complaints occur, the staff know at the time there was a problem.17 Point-of-impact intervention simply recognizes this fact and puts a tool in the hands of the caregiver to resolve the problem at the patient’s bedside, the “point of impact.” The tool consists of the following steps:

1. Identify the problem and address it immediately.

2. Establish the fact that you know there has been a breakdown.

3. Wipe the slate clean.

4. Establish their expectations—what’s the delta between their expectations and their experience?

5. Negotiate and resolve issues.

6. If possible, meet their expectations.

7. Offer reasonable alternatives.

8. When all else fails, offer an alternative person to talk to.

These eight steps simply represent a disciplined approach to ensuring that we address the patient’s expectations in real time so that we do not make the incident report bigger than the incident itself. Of particular significance is step 4, because many times the patient feels the staff has not met their expectations. Ensuring that the team goes back to the patient to reestablish their expectations is key to point-of-impact intervention, which dramatically reduces patient complaints by addressing them at the bedside, before the patient leaves the emergency department.

HARVESTING COMPLIMENTS, CULTIVATING COMPLAINTS

What causes compliments and complaints? For compliments, it is real or perceived A-team behaviors or processes; for complaints, it is B-team behaviors or processes. Leaders and managers must “harvest compliments” to discover what A-team behaviors and processes result in exceeding expectations and creating a positive patient experience. And they must “cultivate complaints” to understand the source of B-team behaviors and processes, which cause a failure to meet expectations. For this reason, all compliments and complaints should be discussed openly at team meetings so that group learning can occur.

Start Doing Smart Stuff, Stop Doing Stupid Stuff: Start Creating a Signal of Hope

Since the emergence of the science of performance improvement, lean management, and patient safety, leaders have come to understand the reality that many of the systems and processes by which healthcare operates produce inefficient, suboptimal results with unintended, wasteful consequences. Simply stated, we do a lot of “stupid stuff.” “Stop doing stupid stuff” should be a model for all healthcare leaders, since this sends a signal to the team that its leaders are serious about creating a commonsense culture where systems and processes not only produce results but also allow for personal and professional fulfillment of the team.

Have the Courage to “Take on the EHRs”

Another area where both culture and systems and processes intersect is the EHR, which has been a major source of burnout, particularly with physicians and nurses. Chapter 11 addresses the specific strategies and tactics for taking on the EHR. Leaders must start this process by showing the courage to stop saying, “That’s just the EHR. You have to get used to it,” and stand up for those who are forced to use it. That’s a cultural issue, not just an operational one. Start with a clear and transparent commitment on the EHR that makes it clear that leaders recognize the horrible impact it can have on our teams and their tendency to burn out.

The Chief Wellness Officer Dilemma

One indicator of the seriousness with which a healthcare organization is taking the burnout epidemic is the appointment of a senior-level person whose responsibility it is to coordinate the diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of burnout. For most organizations that have chosen this path, the title for this person is usually chief wellness officer (CWO). It is currently not known how many healthcare systems have created such a position, their qualifications, their span of control or influence, or their impact, although a group of clinicians affiliated with the National Academy of Medicine’s task force on wellness has issued a call to action for the creation of this position.49 Stanford’s WellMD program offers a course for CWOs,50 and the Massachusetts Medical Society and Massachusetts Health and Hospital Association have made hiring a CWO one of their three recommendations to combat burnout.51

The arguments for such a position are straightforward and include the following:

• the moral imperative to address burnout

• the negative impact of burnout on quality measures

• the ROI from a financial perspective

• the ability and experience of senior-level leaders to address quality (chief quality officer), information technology (chief information officer), and even patient experience (chief experience officer)

(The impact on quality is a powerful argument. Tolerating the conditions that produce burnout requires being able to state, unequivocally, “I am willing, as the CEO [or COO, chief medical officer, or chief nursing officer] to accept inferior patient care!” That negative consequence is as unavoidable as gravity.)

Should healthcare organizations make such an investment? As a former theology major, I was always taught that the answer to any intelligent question is, “It depends.” In this case, my view is that it depends on the following:

• Who does the CWO report to?

• What are the qualifications?

• What is the job description?

• What is the budgeted amount of time for the position?

• What is the budget for the program, or is it just one person?

REPORTING RELATIONSHIP

If CWOs report to anyone but the CEO (or perhaps the COO), they will lack senior-level commitment to making effective changes. Think about the fact that culture, the hardwiring of flow and fulfillment (systems and processes), and personal resiliency will all need to be addressed for the CWO to be successful. For example, if it is discovered that the culture and the systems and processes by which care is delivered are producing unacceptable levels of burnout, how can changes be made in those core aspects of the enterprise without the considerable leverage of either the CEO or COO? I would not advise someone to take on this role unless they report to the top. Anything less is a recipe for failure and frustration.

QUALIFICATIONS

Does the CWO have to be a physician? No, because the skills needed to succeed are neither innate nor exclusive to physicians. But if the organization has a culture in which physicians will not effectively listen to anyone other than a physician to make fundamental changes, then the answer is yes. (Which of course suggests that the culture needs to be changed.) Two of the best CWOs I know have PhDs in psychology (Bryan Sexton at Duke and Ryan Breshears at Well-Star). In practice, about two-thirds of CWOs are currently physicians, with the rest being nurses or behavioral psychologists. Some organizations have both a nurse and a physician working together in the role. The most important qualifications are significant experience in a clinical role, to engender the required respect of the team, and a deep and abiding passion for the plight of those who are burning out.

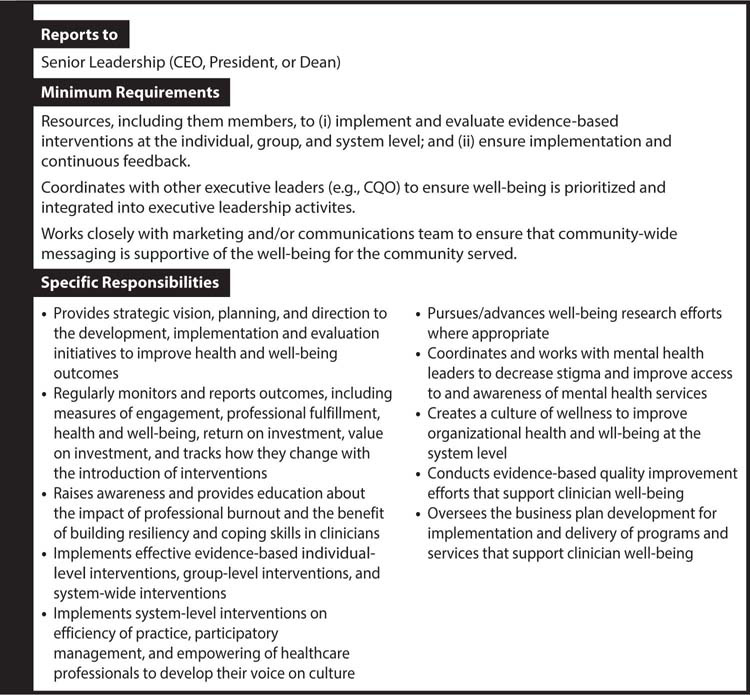

JOB DESCRIPTION

The National Academy of Medicine has provided a template for a set of responsibilities for the CWO (Figure 9-4). This and other descriptions often speak to the need to facilitate, coordinate, and work closely to make system-wide changes, including the implementation of evidence-based interventions to enable clinicians to do the following:

• effectively practice in a culture promoting their well-being

• develop personal resiliency as a priority

While those are worthy goals, I confess to uneasiness when I hear the term facilitate, as it connotes a frustration and futility that places that person in an untenable position. If it is that person’s job to facilitate, is it the responsibility of the other C-suite members (and their direct reports) to “be facilitated”? Do those people have language in their job descriptions to the effect that being facilitated and cooperating with that facilitation is an important part of their job? I doubt it. This is not meant as pessimism, or even a healthy dose of much-needed reality, but a realization that the metrics for wellness and burnout must be a significant part of the organization’s scorecard to allow the “data, delta, decision” approach I have proposed. Finding the sources of burnout alone is ineffectual unless changes can be made at the top levels of leadership to change the system.

CASE STUDY

Gretchen Nordstrom accepted the position of CWO at a large healthcare system, which recognized it had a problem with burnout and turnover of its physicians and nurses. After three months on the job, she discovered that the culture and the systems and processes were directly related to the increasing issue of burnout. She pointed out, privately and in meetings, that unless the culture and the systems were changed, it was unlikely that burnout could be prevented or treated. In a meeting of the senior leadership team, the COO said, “Your job is to facilitate and coordinate, not to make decisions—that’s my job. Besides, our operational metrics are the best they have ever been.”

In this case, the COO seems to be willing to trade the costs of the suffering of burnout for the expediency of short-term results. It will be difficult or impossible for Dr. Nordstrom and her colleagues to change culture and systems in such an environment.

Any job description that translates to a passionate, empowered, and influential central advocate for the health and wellness of the workforce is the key to success.

BUDGETED TIME

For all but the smallest of healthcare systems, if the problem is significant enough to warrant a CWO and senior management and the board have recognized the ROI of effective burnout solutions, the position warrants at least a 75 percent time commitment, as well as support staff necessary to conduct and analyze burnout and fulfillment surveys and conduct leadership and resiliency training. Some systems have dedicated a full-time commitment and commensurate salary. (CWOs should always maintain some clinical responsibilities, partially because that maintains a sense of verisimilitude among one’s clinical colleagues.) A colleague who burns with passion on burnout and resiliency recently asked my opinion on whether the CWO job she had been offered could be done “with a 0.5 FTE [full-time equivalent] time commitment.” I responded, “What the organization is telling you is 1) they view the position as an FTE, not a passionate person committed to make meaningful change, and 2) [they have] a halftime commitment to solve about half the problems … Which half?” She declined the “opportunity.”

Figure 9-4: Sample Job Description for Chief Wellness Officer Position

BUDGET

The ROI for well-being programming in both healthcare and other industries has been proved in several studies, with effects on quality, productivity, turnover, malpractice cases, and employee satisfaction and fulfillment.52–53 Data from the Ohio State University are particularly encouraging.54 These results are unlikely to occur without the appropriate budget to include, at a minimum, administrative support, decision-support access, staff to administer and analyze data, and sufficient support for ongoing training across the institution.

SUMMARY

While there is a great deal of enthusiasm regarding the appointment of CWOs, it remains to be seen whether they will have the intended effects or whether Merton’s law of unintended consequences will apply. For example, if the CWO is unable to make necessary changes in culture and the hardwiring of flow and fulfillment (systems and processes), then it is highly likely that the team will view this as a failed effort—at best—and yet another unfilled promise or management style du jour at worst, further increasing frustration and causing even more burnout.

This is not to say that these positions cannot be highly successful, but rather that the mere creation of the position alone is not nearly enough to ensure success. Reporting to the CEO is ideal, but COO reporting will probably occur in most organizations. There could be real battles there, with a dynamic tension between the financial and infrastructure needs identified and put forward by the CWO and the financial reality that the COO will, in almost all healthcare systems, have to find ways to finance such activities in a revenue-neutral fashion, given the significant financial constraints facing hospitals and healthcare systems.

Most healthcare systems have chief quality officers and chief information officers. One test of how easily accepted the CWO position will be is how easily the chief quality and chief information officers were accepted by the leadership team and the medical and nursing staffs. Were they viewed as a welcome addition that added value to the work and the team who does that work? Or were they viewed as “yet another C-suite member to oversee my work”? The answers to those questions are good barometers of the likely success of the CWO.

Using the Love of Meaningful Work or “Deep Joy”

An intriguing idea that represents a fundamental change in culture (as well as personal resiliency) is tapping into the individuals’ “love” responses from the “love, hate, tolerate” tool to identify what they feel is the most meaningful work they do. Stated another way, “What is your deep joy?” Tait Shanafelt and his colleagues studied the extent to which individuals can focus their primary efforts on the self-identified aspect of work they found most meaningful.55 They found that if their group of academic faculty were able to focus 10–20 percent of their time on the self-identified meaningful work, the burnout rates dropped by 50 percent. As they said, “This suggests that physicians will spend 80% of their time doing what leadership wants them to do provided they are spending at least 20% of their time in the professional activity that motivates them.”55 Tapping into self-identified meaningful work, passion, or deep joy could be highly effective means of using intrinsic motivation as an important part of the culture.55 While this work was done in an academic faculty environment, I have found it a useful way to help team members (not just physicians) identify what motivates them and ensure that they have commitment from the organization to help them pursue this. I have called it “singing with all your voices,” meaning developing an understanding that in healthcare, all of us have a wide range of professional tasks and areas of expertise. A commitment to understanding what we love—the most meaningful part of the work we do—and developing that passion is important, even as we retain an understanding that there are other parts of the job we don’t love. And we do have “other voices,” meaning other talents and the sense of meaning deriving from them, but we must be attentive to discovering them.

Summary

• A suite of solutions assists in creating a culture of passion and personal resilience.

• All healthcare team members are leaders of their part of healthcare all day, every day.

• Redesign performance assessments to shift them from “neocolonialism” to meaningful coaching, mentoring, and transparency.

• Lead from the front to change culture.

• Embody servant leadership in all actions.

• Dream great dreams to create a great culture.