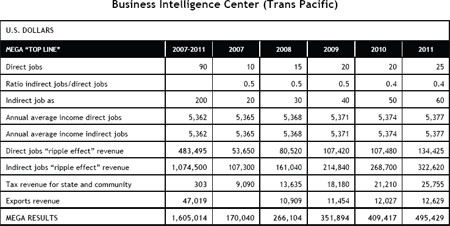

A unique, yet powerful application business case model has been developed by Bernardez16 and has been applied successfully in both the public and private sectors. He has created and validated a unique and powerful 2-level business case model. The model collects and applies metrics for both the elements of a conventional bottom line for an organization (e.g., profit, jobs) and links that with a societal (Mega) bottom. In this approach, Micro— individual performance contributions—are included. Table 3.2 provides an example for an incubator business organization associated with a Mexican University. It shows how Mega and Macro and Micro results can be computed to show a conventional as well as a societal (Mega) return-on-investment:

Table 3.2. An example of an application of Bernardez’s 2-level business case.

To prove success and value added for your planning, this model can be used “before the fact” to project returns and “after the fact” to prove ultimate value and return. In the example in Table 3.2, the ratio of conventional return-on-investment and the one for social (Mega) return-on-investment are shown so that a rational decision can be made on the basis of feasibility of including the Mega consequences.

Another of a large-scale application was a two-level business case done for the leadership and cabinet of Panama, where it was applied to show the costs and consequences of transforming a major city from disrepair, crime, and poverty to put it on a par with the country’s successful metropolis. The application of the Bernardez model provided the president and cabinet with a strategic option so that Colon City could be transformed, including buildings, infrastructure, and all aspects of the city, and that there would be a positive return-on-investment within the first year.17

For more limited estimates of value added. If one is only interested in costing-out training and only to the level of profit-and-loss for an organization but not including societal value-added, Phillips18 provides some guidelines. Of course, adding societal impact and consequences are basic to Mega thinking and planning.

These ways of measuring progress and success will be revisited in Chapter 8, Implementing the Mega Plan.

What if my boss or my associates are not ready for Mega? They might not be at first. You may help them to see the wisdom in their making better choices. And recent concerns in main-stream business as well as public sector organizations (both in the United States and abroad) show that a primary focus on societal value added is evolving.

But you can “educate” others, including a boss. You can help them see the benefits of thinking and planning Mega as compared to the costs for not doing so. If they don’t want to add value to their clients and the shared communities and society in which we all live, what do they have in mind? Who will be called to account for not adding measurable value to all stakeholders? Will they be able to defend their decisions in the harsh light of publicity?

When there is initial resistance, it is often about fear: fear of not knowing how to add societal value, fear that no one else is now doing that, or fear that they don’t have enough control over what gets used, done, produced, and delivered in terms of the impact all of that has on both the bottom line and consequences for our world.

One possibility for not “seeing” the importance of a Mega focus is saliency—how important it is to a person. If one doesn’t see that survival and self-sufficiency is not staring them in the eye—no immediacy—they might defer doing anything about Mega. The closer one is to the survival lever (such as when in a war, or facing a devastating health situation, impending natural disaster, imminent threat), the more Mega seems important. To deal with possible denial is to help people see the real links between what they use, do, produce, and deliver and measurable societal consequences. When given the cool and rational opportunity to consider their choices—organizational alone or organizational + external clients and society—most make the practical choice.

To help, see the decision guide in Table 1.1 for working with others to get agreement on Mega: it provides a self-check that you and others in your organization can use to reinforce the choice of Mega, using the Ideal Vision for performance indicators, for your individual and organizational success.

Undecided? To paraphrase President John F. Kennedy in his inaugural address: If not now, when? If not us, who?

Action Steps

1. Use the Ideal Vision as the basis for everything you and your organization uses, does, produces, and delivers to our shared society.

2. Realize that Mega is the rational, practical, and ethical choice.

3. Get commitment to the Ideal Vision and identify those elements that you and your organization now target and will continue to target and deliver. Table 3.1 and Figure 2.4 will be useful.

4. Measure value added for each initiative, program, project, or activity. There are several that you may use, including C ≤ P. Also, of major value is the Bernardez 2-level business case that can demonstrate conventional bottom-line results (Macro) and societal bottom-line results (Mega).

Endnotes

1. Mager, R. F. (1997). Preparing instructional objectives: A critical tool in the development of effective instruction. (3rd ed.). Atlanta, GA: Center for Effective Performance.

2. c.f. Kaufman, R., Stith, M., & Kaufman, J. D. (Feb. 1992). Extending performance technology to improve strategic market planning. Performance & Instruction Journal, 31(2), pp. 38–43.

3. Table 2.1 shows the three levels of planning and results.

4. The process for defining and using Mega relies on the democratic process of all persons who could be impacted by the definition of Mega coming to agreement.

5. This was derived by asking people from around the globe (not formally including Central Africa or the former Soviet Union, however) to define the world they would create for their children and grandchildren. In earlier work (Kaufman, Oakley-Browne, Watkins, & Leigh, 2003) this was also called “mother’s rule” because it squares quite well when mothers, regardless of culture, are asked what kind of world they want for their children; they don’t talk to means and resources but to ends and consequences related to self-sufficiency and self-reliance.

6. Based on Kaufman, 1998, 2000, 2006; Kaufman, Oakley-Browne, Watkins, & Leigh, 2003; Kaufman, Guerra, & Platt, 2006.

7. In earlier work, I called the use of Mega “practical dreaming”— a concept that management expert Wess Roberts thought appropriate enough to reference in his writings.

8. See the United Parcel Service’s “sustainability report” at http://www.sustainability.ups.com/community/Static%20Files/sustainability/Highlights.pdf

9. Ian Davis (2005) noted some of the following as sensible corporate behavior relative to strategic planning and corporate responsibility:

• A shift away from the “create shareholder value” model to social contribution.

• Organizations must build social issues into strategy.

• “Social issues are not so much tangential to the business of business as fundamental to it.”

• Companies that treat social issues as either irritating distractions or simply unjustified vehicles for attacks on business are turning a blind eye to impending forces that have the potential to alter the strategic future in fundamental ways.

• The “business of business is business” outlook obscures the requirement to address questions about their ethics and legitimacy.

• There is an implicit contract between big business and society.

• Business leaders have to shape the debate on social issues by establishing ever higher (but appropriate) standards of integrity and transparency.

• Rousseau’s social contract helped to seed the idea that leaders must serve the public good, lest their own legitimacy be threatened. Today’s CEOs should take the opportunity to restate and reinforce their own social contracts in order to help secure, for the long terms, the invested billions of their shareholders.

From Ian Davis, world-wide managing director of McKinsey & Company. The biggest contract. The Economist. London: May 28, 2005. Vol. 375, Iss. 8428, p. 87

10. Kaufman, R., & Bernardez, M. (2005). (Eds.) Performance Improvement Quarterly. Special invited issue on Mega planning. Volume 18, Number 3. pp. 3–5, www.ispi.org/ publications/piqtocs/piq18_3.htm

Kaufman, R., Bernardez, M., & Guerra-Lopez. (2009) Eds. Performance Improvement Quarterly. Special invited issue on Mega Planning. Volume 22, Number 2. www.ispi.org/ publications/piqtocs/piq18_3.htm

11. I am getting less lonely since my first publication on the importance of all organizations adding measurable value to our shared society in 1969. Kaufman, R. A., Corrigan, R. E., & Johnson, D. W. (1969). Towards educational responsiveness to society’s needs: A tentative utility model. Journal of Socio-Economic Planning Sciences. 3, pp. 151–157.

Still, there are those who believe that the starting and end-point of any performance improvement effort is the “business case.” Until recently, the standard business case almost never formally looks at a proactive approach to adding societal value. The world is catching up concerning Mega and adding value to our shared society, as well it must. Bernardez has developed and validated a two-level business case including and linking Macro and Mega:

Bernardez, M. (2009). Minding the business of business: Tools and models to design and measure wealth creation. Performance Improvement Quarterly, 22(2), pp. 17–72.

12. Muir, M., Watkins, R., Kaufman, R., & Leigh, D. (April 1998). Costs–consequences analysis: A primer. Performance Improvement, 37(4), pp. 8–17, 48.

Kaufman, R., Watkins, R., Sims, L., Crispo, N., Sprague, D. (1997). Costs–consequences analysis. Performance Improvement Quarterly. 10(3), pp. 7–21.

13. Muir, M., Watkins, R., Kaufman, R., & Leigh, D. (April 1998). Costs–consequences analysis: A primer. Performance Improvement, 37(4), pp. 8–17, 48.

14. Bialik, C. (Nov. 5, 2010). That $150 pack of cigarettes. Wall Street Journal Blog. Bialik, C. (Nov. 6, 2010). The pitfalls of calculating bad behavior’s true cost. The New York Times.

15. Another useful tool for documenting Mega/societal related gaps is provided at gapminderworld (gapminder.org).

16. Bernardez, M. (2009). Minding the business of business: Tools and models to design and measure wealth creation. Performance Improvement Quarterly, 22(2), pp. 17–72.

17. Bernardez, M., Kaufman, R., Krivatsy, A., & Arias, C. (2011). City doctors: A systemic approach to transform Colon City, Panama. Social and Organizational Performance Review, Vol. 3, yr. 3. The title of this article was provided by The Panamanian Minister of Tourism for his briefing to the cabinet.

18. Phillips, P. P. (2010). Converting measures into monetary value. Chapter 14 in ASTD Handbook of Measuring and Evaluating Training. In Phillips, P. P. (Ed.). ASTD: Arlington, VA: pp. 189–200.