6 Analyzing the Information

The discipline, the culture of how you approach

information is what’s important.1

—Jack Devine,

author, Good Hunting: An American Spymaster’s

Story, former head of CIA operations outside the

United States

Truth gives you a critical sense of direction and focus; a deep and meaningful understanding of reality.2

—Ray Decker,

former GAO director, Combating Terrorism

Assessments, and retired intelligence officer

Enter the search “Why didn’t we stop 9/11?” into a search engine and you will probably get what I got: more than 22 million results. At the top of the list is an April 17, 2004 satirical piece by Pulitzer Prize–winning journalist Nicholas Kristof in the New York Times. Kristof imagines a conversation between a CIA briefer and President George W. Bush, who utters “Gosh” and “Whoa” when hearing about intelligence related to Osama bin Laden. Although the make-believe exchange suggests that the data points had come together to create a picture of exactly how bin Laden was going to attack, Kristof is careful to note that “[s]uch an imagined conversation is a bit unfair because it has the clarity of hindsight.”3

Unfortunately, many other discussions about the subject weren’t launched by rational people like Kristof. In article after article, you see attacks on America’s failure to analyze the available data—the supposed intelligence malfunction that’s now widely referred to as a “failure to connect the dots.” One April 26, 2008 article—“9/11 Was Foreseeable”—lists various pieces of evidence to support the assertion of the title.4 And who does the article say was to blame? It’s a very impressive list that includes the FBI, National Intelligence Council, CIA, Federal Aviation Administration, Department of Justice, NSA, Pentagon officials, and North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD). Even author Salman Rushdie supposedly had a heads-up that something might happen. Hyperlinks litter the page, so I decided to find out where they went.

My following of the links yielded this sampling of results, many of which were plagued by link rot:

![]() The source of the Salman Rushie evidence involved a dead link.

The source of the Salman Rushie evidence involved a dead link.

![]() The source of the assertion that Condoleezza Rice was warned on September 6, 2001, that a terrorist attack inside the United States was imminent was Senator Gary Hart, who had just given a speech on terrorism and made an appointment with Rice to share his concerns.

The source of the assertion that Condoleezza Rice was warned on September 6, 2001, that a terrorist attack inside the United States was imminent was Senator Gary Hart, who had just given a speech on terrorism and made an appointment with Rice to share his concerns.

![]() The source that U.S. officials had received warning in 1998 of a “bin Laden plot involving aircraft in new York and Washington” involved a link to CNN’s home page. A search of the quoted phrase on the CNN site leads to a news-analysis piece by a CNN columnist.

The source that U.S. officials had received warning in 1998 of a “bin Laden plot involving aircraft in new York and Washington” involved a link to CNN’s home page. A search of the quoted phrase on the CNN site leads to a news-analysis piece by a CNN columnist.

![]() The source of a report to U.S. officials—a report of unnamed origin—that “a group of unidentified Arabs planned to fly an explosive-laden plane… into the World Trade Center” [“…” suggesting missing text is included in the article] also involved a dead link.

The source of a report to U.S. officials—a report of unnamed origin—that “a group of unidentified Arabs planned to fly an explosive-laden plane… into the World Trade Center” [“…” suggesting missing text is included in the article] also involved a dead link.

There are three interrelated points to be made here about data analysis:

1. Check your sources before you contend you have evidence.

2. Use your imagination but remove your biases when you analyze information.

3. When you connect the dots make sure you know they belong there and how they relate to each other.

Checking Sources

This section is designed as a complement to the discussion in Chapter 2 on vetting sources. That chapter focuses on human sources of information with whom you’re communicating, and determining their level of truthfulness. The focus here is written and video/audio sources. In this era of Web-based fact-finding, it principally means that you need to learn to vet the Web.

Charles Seife, a journalism professor and author of Virtual Unreality: Just Because the Internet Told You, How Do You Know It’s True?, uses an analogy with epidemiology to describe the “disease” of untruth that has infected the World Wide Web. He says, “What makes a disease scary is how quickly it spreads from person to person, how long it persists, how quickly it mutates and changes.”5 Information that has gone viral can get around the world instantly, persist for years, forever alter our lexicon of search terms, and, true or not, influence our beliefs. He therefore calls digital information an “infectious vector,”6 meaning that is an agent carrying and transmitting an infection—in this case, flawed information—from one person to another.

In a conversation with Jack Devine, former head of the CIA’s spying operations and co-founder of The Arkin Group, he gave me an example how this could work with either print or digital information:

What you have is false confirmation. I give you an opinion about some piece of news in this interview, Maryann. You tell a reporter friend of yours at the New York Times. The New York Times publishes an article that suggests the opinion is fact. The Economist picks it up. I’m sitting here reading the Economist and thinking, “Gee, that information I shared with Maryann must really be good because it’s surfacing in all these different places.”7

This phenomenon can occur in simple, silly ways, and incorrect information is then passed around as factual. For example, in 1973, I mis-heard one of the lyrics to “Live and Let Die,” the theme song written by Paul and Linda McCartney for the James Bond movie of the same name. Being a smart-aleck student, I told one of my friends about the “fact” that there was an egregious grammatical error in the song. About 30 years later, we happened to be listening to the song and she mentioned that it always bothered her that it contained that error. In those intervening years, I had learned what the actual lyrics were and told her that I had been mistaken in 1973. Of course, when the song came on and she was with another person, she would sometimes point out the supposed grammatical error—with everyone hearing the same thing. My mistake had not only given life to a falsehood, but it had also affected people’s hearing!

The disease of untruth even applies to the creation of people. In an NPR/Public Radio International interview entitled “A Web of Doubt,”8 Seife briefly described the algorithms for producing fake people—that is, friends on Facebook or followers on Twitter who don’t exist. One keyword that he said crops up a lot in association with these fake people is “bacon.” So the “people generator” might pair the word “bacon” with “specialist” and create a bogus profile. (Seife actually researched how many “people” on Twitter listed themselves as “bacon specialists” and found 2,100. Many of them shared other nouns, including alcohol, pop culture, guru, and fan.) The non-existent person then connects with others via social media and takes on a life of its own; when followed back, the creator can push links or raise the standing of a person or site in search engines. The Motley Fool, a company and Website formed to help people invest more wisely, quantified the problem in an article titled “Twitter’s Very Real Fake Problem.”9 The fact that 44 percent of Twitter’s 974 million users have never tweeted hints at the problem, but the following numbers give it meaning we can relate to: “StatusPeople’s Fake Follower Check tool, which uses an algorithm to determine how many followers are fake or inactive, revealed that 80% of President Obama’s 42.5 million followers are fake or inactive accounts, as are 75% of Lady Gaga’s 41.3 million followers.”10

Another common deception is real people creating fake profiles to review books (positively and negatively), argue politics, discredit scientific studies, and much more. Seife calls these make-believe personalities sock puppets. In 2012, Facebook revealed that nearly 10 percent of its accounts—83.09 million—were phony.11

We don’t even know for sure how people really look. Here’s a photo of me, used on page 62 of a book I coauthored with Gregory Hartley called The Body Language Handbook.

Because the point of the photo was showing my hand doing a self-soothing gesture called an adaptor, I didn’t think anyone would call us dishonest if I used Adobe Photoshop to eliminate some of the wrinkles underneath my right eye. If I invest in a better eye cream at some point, then the photo might be an accurate representation of my appearance. This touch-up doesn’t have the drama of those done with countless celebrities whose body parts are often slimmer and smoother than Barbie’s by the time they show up in magazines. You are not necessarily being mean-spirited if you wonder what a movie star really looks like. You’re curious; that’s a good thing. The paparazzi thrive on the premise that you want to know “the truth.”

All of the falsehoods flying from different directions can profoundly affect people’s judgment and, ultimately, their beliefs. A good example is the anti-vaccine lobby, well-organized on social media and promoting a point of view, but often presenting it as though it were science. When enough people adopt a point of view, blog posts and articles proffering it as science start showing up. One of the most common messages in the anti-vaccine movement has addressed a link between the measles vaccine and autism. For 12 years, Andrew Wakefield’s work gave the supposed link the clout of scientific research. But in February 2010, The Lancet retracted the 1998 article by Wakefield, who was found guilty of professional misconduct and stripped of his medical license. Unfortunately, that was 12 years of false information affecting the health and lives of children.

Wikipedia has given contributors the power to create facts. To clarify, the information in an entry can begin as a lie, but it becomes true. The mechanism for doing this is to edit a profile with bogus information, use a fake source in the endnote and hope the fact-checkers at Wikipedia don’t pick it up (they do try!), wait for it to get picked up elsewhere, and then cite a legitimate source that picked it up in a revised endnote to the Wikipedia reference.

This is how baseball’s popular outfielder Mike Trout got his nickname “The Millville Meteor.” A fan posted the moniker on the forum pages of a Website—Trout is from Millville, New Jersey—and someone who saw it thought it would be fun to revise the rising star’s Wikipedia entry with the nickname. The rest is history. An authoritative source of nicknames and statistics, Baseball-reference.com, picked it up. People began calling Trout “The Millville Meteor.” After first expressing surprise over it, he decided to embrace it.

This recounting of how we are so easily duped and deluded by Web-based and other written sources would not be complete without the tale of Ryan Holiday, the man who made reporters at several top news outlets look like the kind of fools who believe a Nigerian prince is about to wire them money. Rather than blame the reporters for being gullible, let’s look at how Holiday gave all of us a blast of cold water in the face. If we don’t sufficiently question what we’re told or what we read, we might as well send our bank account information to the Nigerian prince.

Twenty-five-year-old Holiday subscribed to a free service called Help a Reporter Out (HARO), which sends daily queries from journalists in need of certain types of experts. The categories are just about anything you can think of, from highly technical topics to general interest and pop culture subjects. With the help of an assistant, Holiday pitched himself in response to all the queries. In a matter of weeks, he was barraged with requests for his expertise. He became a fount of insights on topics about which he knew either nothing or not much: “Generation Yikes,” chronic insomnia, workplace weirdness (pretending someone sneezed on him while working at Burger King), winterizing a boat, and vinyl records. The last piece ran in the New York Times, which joined Reuters, ABC News, CBS, and MSNBC among the major outlets falling for his false stories.

No one had done the simplest homework on him, or they would have discovered that his book, Trust Me, I’m Lying: Confessions of a Media Manipulator, was set for imminent release. Amazon.com is a great tool for finding out weeks, or even months, in advance when a new book is coming out.

I asked Holiday what advice he would give to people in need of information to avoid being duped. The first of three tips he gave was aimed at journalists: “Don’t use services like HARO.”12 With a background in corporate public relations, I can understand his caution. It used to be my job to connect the executives and organizations I supported with current news and journalists writing stories about their areas of expertise. It’s tempting to get creative about the relevance of your client’s or your boss’s expertise to a story. And the closer the reporter got to his or her deadline, the greater were your chances of slipping a quote from your “expert” into the story.

The other two tips would apply to anyone if you broadly interpret the concept of “story”:

![]() Don’t let sources find you. Find your own sources.

Don’t let sources find you. Find your own sources.

![]() Let the sources influence the story. Don’t use the sources to fill in the story you’ve already written.

Let the sources influence the story. Don’t use the sources to fill in the story you’ve already written.

Be skeptical about everything you read and hear. This is hard to do for most of us who are (thank goodness) trusting people surrounded by people we can trust. But that reality makes us complacent when it comes to reporting and blogging. I have gone to extremes to document the insights and studies in this book, and provided you with endnotes so you can confirm or challenge my conclusions. But it’s possible that I’m wrong about a few things, or that my sources are wrong about a few things. Challenge the assertions. Check your sources.

Using Your Imagination

I learned classic stories related to information analysis in my many visits to the International Spy Museum in Washington, D.C., but none stands out more than historian Roberta Wohlstetter’s insights about what happened—and what did not happen—at Pearl Harbor in 1941. In her book, Pearl Harbor: Warning and Decision, Wohlstetter lays out the copious facts that indicated that Japan was a threat to the United States and was within striking distance. She asserts that despite having sound intelligence, the United States took no action to avert the attack because of a “failure of imagination.”13 No one in power believed Japan would do what it did. Embedded in that perception was that, to some extent, U.S. leaders focused on the similarities between the United States and Japan in drawing the conclusion that Japan wouldn’t bomb a U.S. territory.

Wohlstetter’s analysis suggests, therefore, that people may not see the truth, even though all of the elements necessary to see it are right in front of them, because their thinking is constrained. Assumptions, biases, rules, customs, or other factors at play put a box around the analyst’s imagination. For example, the suspecting husband concludes that, despite changes in behavior and midnight phone calls, the wife couldn’t be cheating because he wouldn’t do such a thing. The professor assumes that the D student who got an A on the last test just studied hard, instead of giving credence to information that he stole a copy of the test; it’s what he wants to believe.

Ray Decker has observed successful efforts among CIA, Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA), and other federal analysts to avert failures of imagination. Decker is a retired intelligence officer and federal senior executive who was the director responsible for Combating Terrorism Assessments at the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) before and after the attacks of September 11, 2001. The GAO is responsible for evaluating and assessing federal programs to ensure they are being executed smartly and that there is good stewardship with the funds allocated by Congress to achieve the desired result. Given the agency’s mission, GAO analysts have to determine whether or not the programs are achieving what they are designed to achieve. They explore the cause of program failure or inefficiency and recommend solutions for improvement. Part of Decker’s responsibility was leading the effort to analyze the capabilities of federal teams responding to terror threats and ascertain opportunities to improve coordination among those teams.

During his decades working with numerous intelligence officers and analysts in the field, he concluded:

The best analysts I worked with were those who didn’t just think outside the box; they refused to see a box. They would look at a problem and not constrain themselves by saying, “This is about aircraft, so I can only think in terms of aviation.” No, they would draw from medicine, or sports, or any field that could provide insights about how pieces of information might fit together. They would use any and all approaches to analyze the problem, and not assume that there is only one answer.14

When I was in college, I took a course called “Philosophy of Science.” During the first week, I followed the lectures and conversations fairly well. For the next 14 weeks, I would sit in class, and much of the time I would wonder what everyone was talking about. My major was speech and drama; I probably had no business being in a class that required some working knowledge of theories in physics and other sciences. The one enduring thing I took away from the class related to the final exam—which I didn’t understand. It was a take-home essay with a single question about point mass theory. I was supposed to discuss whether or not it was useful. I think my hands were shaking when I gave the paper posing this question to a friend of mine studying organic chemistry. “What does this mean?” I asked. And then she told me that point masses don’t actually exist, though the concept could be really useful in solving certain problems.

Based on that, I wrote an essay and got far more out of the experience than a decent grade. Moving away from point mass per se, it occurred to me that introducing an improbable or impossible premise into analysis helps remove constraints. It widens the field of evidence you will see. It arouses curiosity, helping to eliminate the human predisposition to let our unconscious biases shape our assumptions about the cause of a problem or the route to a solution.

For example, on July 17, 2014, the day after a Malaysian passenger jet was shot down over eastern Ukraine, media outlets reported three possible suspects: separatist rebels in Ukraine; the Ukrainian government, which might do that to frame the rebels; and Russia. Analysts working with both technical data and human intelligence would fail in their mission if they simply embraced those possibilities and tried to use imagery, measurements, signals, and information from field assets to determine which one was true.

One of the broad questions analysts would ponder is: “Who has surface-to-air missile systems?” The answer is the United States, Russia, China, Taiwan, Egypt, Germany, Greece, Israel, Japan, Kuwait, the Netherlands, Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, Jordan, Spain, Poland, South Korea, North Korea, Turkey—just about everybody. Given the situation in Ukraine, it may seem ridiculous to even consider most of these countries as the source of the attack, but not considering them is even more ridiculous if you are an analyst. As Decker notes, “A good analyst does not look for the standard answer—in this case, it must be the Russians, it must be the rebels, or it must be the Ukrainian government. A good analyst wants to be able to eliminate other possible answers. In the end, the correct answer may, in fact, be the standard answer, but you have to go through the process of eliminating the others to be sure.”15

Here’s a frivolous example of the value of introducing an improbable or impossible option into an analytic process. Several years ago, while at the Denver International Airport, I decided to get a CLEARcard. It’s a photo ID that contains fingerprint and iris data; people who have it speed through security checks at airports that accept it. The person processing me got my fingerprints and then had me stand in front of a machine to do the eye scan. He said, “Hmm. That didn’t work.” He took me to a different machine and the same thing happened. For whatever reason, he couldn’t capture the iris data. He called over his supervisor, who repeated the process, first with one machine and then with another. Same problem. I suggested that my contact lenses were the cause, but they assured me that they took scans of people all the time and contact lenses had never been a problem. I got the card anyway because they had the fingerprints.

The first time I told someone this story, I said they couldn’t do an eye scan because I’m from another planet. He laughed and then proceeded to go through all of the reasons he could think of why the scan didn’t work. I was fascinated because my story wasn’t meant to provoke serious thought; I was just trying to be funny. Since then, I’ve told dozens of people the story to find out what their reaction would be. With one exception, everyone speculated about the technical and human reasons why the scan didn’t work. (The one exception is someone who thinks I might be from another planet.)

And so, by posing an impossible or improbable reason for the failed scan, I’ve repeatedly aroused curiosity about possible and probable reasons for the failure, as well as a few that are nearly as far-fetched as the extraterrestrial explanation.

You have control over when and how to apply imagination to the analysis of your own challenges, but you may not in your professional or academic environment. “Failure of imagination” plagues individuals and companies, and sometimes leads to the demise of entire organizations. Decker points out that this ties in directly to the nature of the organization’s leadership:

Many leaders and managers do not appreciate people who are contrarians. They don’t necessarily appreciate answers that upset current policies, viewpoints, opinions, or positions on an issue—which makes it difficult for a creative analyst not just to succeed, but also to survive.

An effective leader, on the other hand, will want to be surrounded by smart people, people who question the status quo, and who do not accept the first answer or the easy answer. That makes life a little more difficult for the leader. There’s more thinking involved in working with people like that.16

In her book, The Power of Paradox, Deborah Schroeder-Saulnier illuminates the practical and massive organizational benefits of analyzing a problem imaginatively through the use of one simple word: “and.” It’s hard for many leaders to rely on “and” thinking because they rose to their positions of the authority by making productive either/or decisions. However, being decisive about choosing X or Y, instead of analyzing whether it’s possible to have X and Y, often precludes the leader from looking at the whole picture.

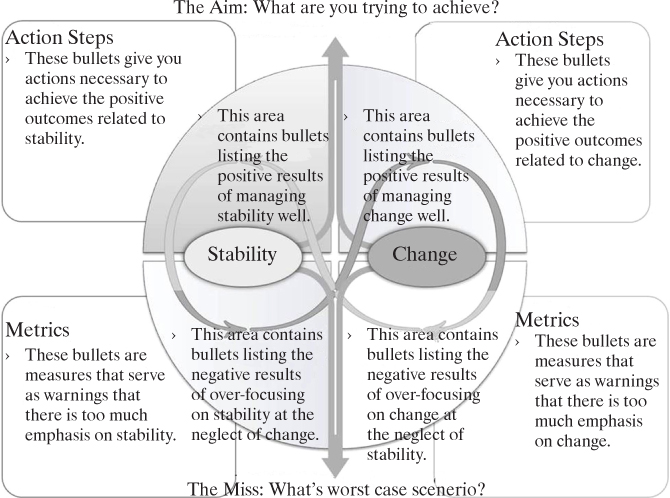

“And” thinking is one type of critical-thinking skill that helps reduce the possibility of failure of imagination. It involves the identification of pairs of opposites and determining how they are interdependent relative to a key goal. For example, a company such as Microsoft or Apple wants to be known for innovation at the same time customers embrace it for its stability. Failure to manage a critical pair of opposite goals like “stability and change” results in the company struggling to maintain market share. The worst-case situation—all too common for many organizations—is that one goal is consistently emphasized over the other, and the company begins a downslide from which it may never fully recover.

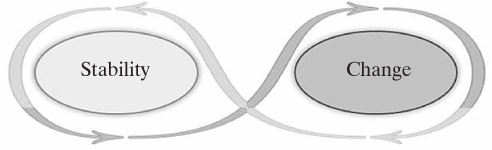

In her book and supporting Website, Schroeder-Saulnier offers models to help people trying to use paradox thinking to create a complete picture of their situation if they put “and” between two conflicting goals.17 It begins like this, with two opposing concepts such as stability and change linked by an infinity loop:

It’s then developed step-by-step to arrive at the complete picture, as shown on page 158.

If you were the president of a country, the way your intelligence analysts might use is this by starting with seemingly conflicting goals such as “reduction in force” (coming out of the domestic issue of the country’s budget) and “escalation of military assistance to an ally” (tied to international relations concerns). They would then proceed to flesh out the model to get a picture of how possible that is. Maybe it’s not, but the model would organize the information in such a way that “why” should be very clear.

And if you are the vice principal of your local high school, you might start by identifying the conflicting goals of “investing in growth” and “cutting expenses.”

Averting a failure of imagination involves systematic ways of exploring “what if?” Your aim, regardless of how you get this outcome, is to remove constraints on your thinking.

Connecting the Dots

Since the attacks on the Twin Towers of the World Trade Center and the Pentagon, the U.S. government has spent billions of dollars to develop mechanical means to improve connecting the dots. Jack Devine, who strongly dislikes the term, is the among the many top intelligence professionals who criticizes this over-reliance on technology to pull together facts to create a picture. He does not see it as getting us closer to the truth:

By connecting the dots without verifying each piece of information, you can arrive at a conclusion prematurely. When you get to the question of imagination, using an automatic process to connect the dots reduces the imagination rather than improves it. You can end up with false information and a lot of extraneous data.

In connecting the dots, you may be linking ideas and facts that have no relationship to each other, cannot be verified, and are out of sequence. If you have intelligence services in Israel, France, and Russia all reporting something, that doesn’t make it true. One might intercept the other’s communications and add the new information to the mix. That’s not verification.18

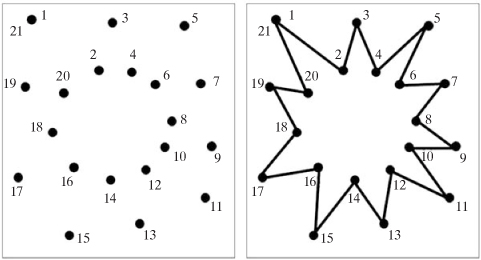

To illustrate Devine’s point, consider the following configuration of dots:

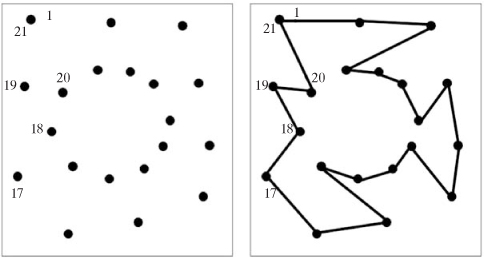

But what if they weren’t numbered? Even if each element of the picture were discretely verified, a gap in understanding how they relate to each other might yield a completely different result. For example, let’s say that analysis of a situation gives both a firm starting point and a clear sense of last five things that happened. Here is a potential graphic depiction of the result.

Devine considers this approach a different kind of “failure of imagination”—the kind in which people analyzing available information draw an immediate conclusion from loosely connecting the dots. A variation of this is going into the analysis with a closed mind about the outcome: “If you have a preconceived notion of what the picture looks like, you will drive the data into holes to create the picture you envision.”19

![]()

In summary, analysis is a process that involves verifying data, opening your mind to the full range of possibilities about what that data tells you, and making connections among data only after you complete the other two activities. As a human being, you will not be able eradicate all biases from that process, but, at the very least, you will go into the process with some idea of what those biases are. Your challenge is to manage their influence on the analytical process.

I have coauthored books with 12 different experts and ghostwritten books for another six experts. All of them are people who are recognized in their field, respected as authorities, and extremely bright. They have impressive CVs and resumes, and my bias is to respect their knowledge base and assume they are right—but it’s a bias I have learned to fight.

With one exception, they have all given me some tidbit of information that turned out to be inaccurate. They didn’t do it deliberately, of course. They simply got one memory confused with another, or had a date wrong, or slightly misinterpreted a concept. This is why I don’t automatically accept what they tell me as factual. I second-guess them. I repeat my question to find out if I’ll get a different answer. I ask for an example. I do research. And I analyze the information using tools such as those described here.

And even after all that, when the book is in your hands and you’re reading it, you might say, “Hey, I was at that event they’re talking about and it was overcast that day, not sunny!” As human beings, we aren’t perfect with information, but most of us try to come as close as we can to the truth.

In the world of intelligence, that’s the goal—not truth in an absolute and perfect sense, but coming close to the truth. In his writings and lectures, Mark Lowenthal, author of multiple books on intelligence and former assistant director of Central Intelligence for Analysis and Production, states that intelligence is not about truth; it’s more accurate to think of it as “proximate reality.”20