THREE

Collaborative Organization Design Research at the Center for Effective Organizations

WE DESCRIBE A RANGE of collaborative research approaches used over several decades in research programs at the Center for Effective Organizations (CEO) in the Marshall School of Business at the University of Southern California. These programs have focused on generating knowledge that is theoretically and practically useful about an unfolding set of organizational effectiveness and design challenges that have confronted companies through time. These programs and their constituent studies have been recursive: The knowledge gained in each project has informed ensuing research. We describe our foundational assumptions about design and design research that have guided our choices of research topics and methodologies, and we discuss the nature and importance of programmatic research approaches to address complex problems. We develop our view that collaboration is critical to organizational design research and describe some key elements of one particularly fruitful collaboration. Finally, we suggest a network collaboration approach that we are using in a current research program to increase relevance and speed of knowledge generation to better address the dynamic issues and innovative designs that characterize today’s organizational landscape.

CEO: The Institutional Base for the Research

The Center for Effective Organizations was founded in 1978 by Edward E. Lawler, who designed it to embody the principles of collaborative, adaptive research, and to focus on key issues of organizational effectiveness. CEO’s mission is to conduct research that generates new knowledge that is (1) useful to and used by the participating organizations as well as useful and accessible to the broader organizational community, and (2) academically useful and valued. Our publication strategy is to report the results of our research in both practitioner and academic outlets. This dual focus combines a collaborative approach (Shani et al., 2007) and rigorous research methodologies that build on existing knowledge. The following pillars support the mission:

1. Building on past knowledge by bringing knowledge of theory and practice to the collaboration.

2. Relating the research to the problems and contextual realities of the participating organizations.

3. Building a collaborative research team with study participants, to incorporate the interests and purposes of all parties to the collaboration.

4. Carrying out related studies in multiple organizational settings in order to discover what knowledge can be generalized and the boundary conditions for its applicability, as well as to elucidate and investigate new theoretically and practically important aspects of the problem.

5. Addressing multiple stakeholder interests by attending to organization, manager, customer, and employee outcomes.

6. Using multimethod research designs that meet the standards of diverse communities of practice regarding legitimacy, validity, and usefulness of the findings; methods that match the problem being studied and that are agreed to by our collaborators.

We have a twofold strategy to access knowledge of practice and to identify research collaborators. First, CEO has built a network of companies who sponsor our mission of carrying out academic research and contributing to practice. These companies provide base funding through membership fees. We learn about the trends in these companies and the issues they are dealing with through regular interaction with their representatives. Second, as theoretically relevant organizational problem areas emerge, we build collaborative research projects with sponsor organizations and other interested collaborators. Research projects are funded by various sources: the participating organizations, government, foundations, or other research partners.

Many of CEO’s studies focus on how organizations and new organizational capabilities can be created or changed by design in order to address problems and opportunities and to increase effectiveness. These research projects focus on new and emerging organizational directions. Our collaborators are often early adopters with whom we can learn about and assess new approaches and contribute to the knowledge required for organizations to use them effectively. The approach is based on the perspective that organizations are social artifacts (Simon, 1969), built and changed by people to accomplish their purposes. The study of organizations is thus the multilevel study of how people as individuals and collectives go about organizing to accomplish their purposes.

Although conceptualizing organizations as dynamic phenomena that are continually being changed and redesigned, we generally employ established analytical social science methods whenever possible. We develop theory grounded in the phenomena of interest, carry out the description and measurement of phenomena in terms of the constructs and their relationships contained in the theory, and systematically assess the impact on outcomes. In that sense our methodology is similar to the University of Michigan Quality of Worklife (QWL) studies described by Mirvis and Lawler in Chapter 6, Rigor and Relevance in Organizational Research. In order to impact the application of research knowledge and to test its validity in practice, we also take a synthetic approach, often working with participating companies to develop and test in situ organizational design methods and tools based on the research knowledge

Research that takes a design perspective is inherently collaborative. Full understanding of designs and design processes involves the combination of different kinds of knowledge. New designs are socially constructed by the participants in the setting, using many sources of knowledge. These sometimes include knowledge from organizational research and always include knowledge from the local communities of practice. Methodologies for applying and testing the design and implementation of new organizational forms include action research (Elden & Chisholm, 1993; Eden & Huxham, 1996; Reason & Bradbury, 2001), and evaluation research (Campbell & Stanley, 1963). Research teams investigating the generation of new practices and designs necessarily include members who have deep knowledge of organizational design principles and processes and who bring theory-based frameworks to complement the knowledge in practice (Galbraith, 1994; Mohrman & Cummings, 1989; Romme, 2003; Romme & Endenburg, 2006; van Aken, 2004, 2005).

Design Research

Several premises underlie our approach to design research. The first is that the field of organization research is a “science of the artificial” (Simon, 1969), similar to engineering and medical sciences. Organizations are purposefully created by people; they are continually re-created through the self-designing activities of people in the organization (Weick, 2003) as they work together and encounter performance challenges or as their purposes change. They are also deliberately designed and redesigned by managers in order to align structure, processes, rewards, and people in support of the organization’s strategy (Galbraith, 1994), and to allow coordination, boundary maintenance, and goal-oriented behavior that links the organization to the external environment.

A second premise is that because organizations and the contexts in which they operate regularly change, organizational practice often precedes academic knowledge. Research methodologies are required that are suited to study organizations as dynamic rather than as fixed entities with enduring features (Huber & Glick, 1993; Lawler et al., 1985). We agree with Kurt Lewin (1951) that the best way to understand organizations is to study them when they are changing. This is true not only because many organizational dynamics are exposed during a period of change, but also because this is the best time to generate knowledge that can contribute to organizational change.

A third premise of design research is that a full understanding of organizations requires three focuses: (1) on the structures and processes that comprise the organization; (2) on the cognitive understandings and behaviors of the human beings whose aspirations and worldviews influence organizational behavior; and (3) on the design processes, formal and informal, that organizations and the people who occupy them use to change organizational structures to better carry out their purposes in a changing environment (Mohrman, Mohrman, & Tenkasi, 1997). These focuses drive us to ask many associated questions, be informed by multiple theories, including theories from practice, and apply an array of research approaches suited to the various questions. Such multifaceted research programs have also been described and advocated by others (e.g., Lawler, 1999; Seashore et al., 1983; Van de Ven, 2007).

Collaboration in Design Research

During the design of a complex system, knowledge, preferences, and purposes from various sources are combined. For example, in designing an airplane, the knowledge of structures, combustion, aerodynamics and materials, software, and information technology, to name a few, are combined along with the aesthetic and instrumental preferences of the designers. In the design process, these specialized knowledge bases are used in the context of the goals for the system being designed and of the other knowledge elements. The same is true in the design of an organization, where design occurs in a system that has a context including goals and strategies and where the knowledge bases, purposes, preferences, values, and aesthetics of various individuals and communities of practice come together. The design process includes the knowledge and preferences of the various disciplines of academic researchers, who are no less than organizational practitioners shaped by their communities of practice and guided by their own purposes (see Chapter 1, Research for Theory and Practice).

We highlight the importance of who participates in the research process for two reasons. First, because the knowledge represented in the research planning and in the designing process will be reflected in how the problem to be investigated is defined and approached. Second, because all design is a political process and allocates value in an organization. The determination of what questions to research, how to frame them theoretically, and how to design the study are all values-based decisions (Ghoshal, 2005). Those who participate have the chance to get their purposes and their knowledge considered and those who do not are at best represented by others.

Organizational designs are evaluated as to whether they foster the accomplishment of the criteria to which they were designed—criteria determined by design participants. Similarly, knowledge created by research is evaluated in terms of the study’s objectives, as formulated by the research participants. If there is no interaction among practitioners and academics about the important questions to examine and the contexts being studied, practitioner knowledge and concerns are ignored and study criteria are misaligned with practice. It is no wonder that such research is neither viewed as relevant nor used. It is equally suspect theoretically when researchers study organizations with little knowledge about the problems practitioners face or their purposes.

Problem-Focused Research

A problem-focused approach has guided much of the research at CEO. Our topics have roots in our own experience-based and theoretical interests in organization, but they emerge and are shaped in close interaction with practitioners. Problem-focused research provides a natural home for and evokes a need for collaboration that brings together multiple perspectives, including those of theory and practice. The most important problems are often not readily resolvable within any current community of practice. They call for the combination of knowledge from multiple perspectives, expertises, and disciplines (Mohrman, Galbraith, & Monge, 2006; Mohrman et al., 1999; Stokes, 1997; Van de Ven, 2007).

Problems create a context in which practitioners are more likely to be open to influence from research. Problems represent anomalies and present a need to step outside the daily reality that is driven by implicit theories and ready-to-hand solutions, and to try to achieve a detachment that enables the search for new understandings that can guide action (Argyris, 1996; Schön, 1983; Weick, 2003). “It is in these moments of interruption that theory relates most clearly to practice and practice most readily accommodates the abstract categories of theory” (Weick, 2003, p. 469).

Programmatic Research

Conducting problem-focused research that yields information useful to organizations in designing solutions to the problems they face most likely requires a program of research rather than a single study. One study does not adequately address a complex problem area, such as how to design a performance management (PM) system that effectively contributes to the achievement of strategy and performance objectives and to future-oriented capability development. Such a system was the focus of one of CEO’s early research programs. We worked with multiple companies through different stages and modes of investigation that included exploratory, descriptive, and action research. These companies were interested in redesigning their performance management systems to be forward-looking business tools not just backward-looking appraisals. The studies examined the individual level, but also manager/subordinate dyads, and larger performance units—always with the purpose of contributing to design knowledge. Participating organizations engaged in the research to learn how to redesign PM to be more effective Business tools (Mohrman et al., 1989). The study in each company exposed the researchers to new aspects of the dynamics of performance management that were evoked by a particular system in its context and the experiential learning that had occurred as part of it. Each study setting thus brought questions to be studied, and in the process of answering them, raised new ones, pertinent to and answerable in another setting with another study.

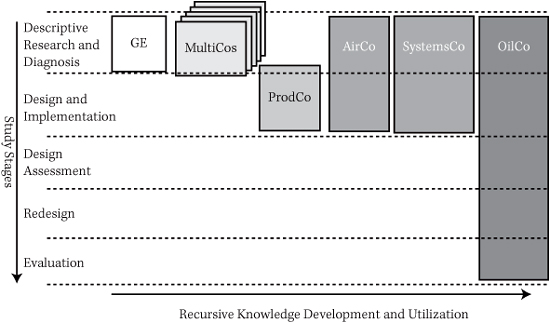

Figure 3.1 shows the sequence of studies that constituted this research program. It began with a study at General Electric. GE’s PM practices had proliferated, resulting in over a hundred different appraisal forms and practices company-wide. GE wanted to determine which approaches best contribute to capability development and business performance. Our CEO research team worked closely with a GE corporate project manager and a steering committee of human resources (HR) executives representing each of GE’s business units. Their input was crucial in defining and planning the study, constructing interviews and questionnaires, and responding to findings.

A government grant enabled us to expand the study into seven very different corporations, each with multiple business units. We consistently found across all eight companies that development of capabilities and business performance are related to: (1) the extent to which the performance management process involves a two-way exchange between the appraisee and appraiser; and (2) the extent of alignment of individual objectives and performance criteria with the unit’s business goals. Particulars of the form used and numbers of rating categories had no impact on the effectiveness of the system. These findings among others provided clear direction for redesign of the systems. For example, focus a system on guiding the processes and not on finding the most accurate measurement instruments.

FIGURE 3.1 CEO’s Program of Collaborative Performance Management Studies

From these initial primarily descriptive and hypothesis-testing studies, we began to test our knowledge in three separate action research projects in which we worked with corporate teams to assess needs and then design and implement new PM systems. This sequence of studies culminated in a longitudinal multiyear study with four large business units of an oil company (“OilCo”) that wanted to design a performance management system to catalyze and accelerate work system change. This study included a baseline, multimethod, and multilevel component to test and extend theory in this increasingly team-based organization. The next phase was to test the knowledge through action in the form of design, implementation, and assessment of new PM systems. A third phase consisted of using the learnings from the assessment in a highly participative iterative redesign, implementation, and evaluation process (Mohrman & Mohrman, 2003).

We believe that multifaceted programmatic research such as this—with many related studies building on one another cumulatively and recursively—at least partially addresses a number of issues that plague management research. The knowledge from early studies provides an enticement to other companies to participate in research and extend knowledge. The research can in this way eventually involve enough cases with sufficient variation to learn about the many features and dynamics of complex, dynamic human systems and the boundary conditions of the knowledge. Such a program of research is not possible without strong collaborations that include people with diverse discipline backgrounds and from diverse communities of practice (see Chapter 1, Research for Theory and Practice, Figure 1.2).

In each program of research, new questions surface for theory and practice that lead to the next program of research. Over the course of the 30 years during which we have used this approach, our research focuses have evolved along with the increase of complexity and connectedness of the global economy and the associated changes in the corporate landscape.

Through the previously mentioned collaboration with OilCo, we developed an appreciation for and theory about the central role that PM can play, either as a key element of change or alternatively as a stubborn barrier to change in a complex organizational system. We became acutely aware of the tight connection between the design of the work system and the design of the performance management system (Mohrman & Mohrman, 1998; Tenkasi, Mohrman, & Mohrman, 1998). OilCo was changing their work systems in fundamental ways as they moved to a more lateral way of operating characterized by cross-functional teams in almost all aspects of their business. They had encountered a problem that they could not solve given current hierarchical conceptualizations of performance management, and they knew they needed to develop new understandings and practices. For OilCo, the knowledge generated in the research contributed to the fundamental redesign of PM.

These final performance management studies and our ongoing interactions with our general sponsor base made us aware of a new problem that companies were facing and for which there was inadequate organizational theory and academic understanding. Companies were struggling with the wide-scale adoption of cross-functional teaming approaches to rapidly solve problems, make improvements, develop innovative products, and meet customer needs. They were finding that the guidance they took from the sociotechnically based teams paradigm being used in factories was insufficient to help them effectively design teams for knowledge work settings. They were also finding, like OilCo, that their organizational systems and processes worked against effective teaming. We began to study the design of team-based organizations in knowledge settings—focusing on the entire organization and all processes, including PM (Mohrman, Cohen, & Mohrman, 1995).

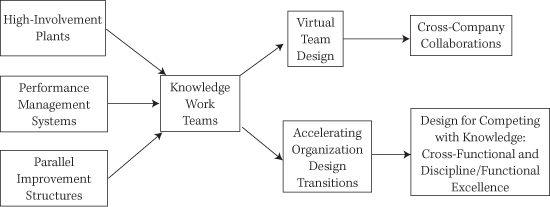

Figure 3.2 shows a stream of CEO’s team research programs. Each research program was a series of related studies building on each other to more fully understand the organizational dynamics and design choices for particular problems. Each program built on the knowledge generated and the new issues that became salient in the previous program. The close collaborations and extensive contact with organizational members that were inherent in our work made us aware of some of the core problems that they were facing. The knowledge work teams (KWT) research built on our earlier work that studied design for high-involvement, organizational improvement systems and high-performance factory systems, and on our performance management and change research. Those KWT studies, in turn, exposed us to theoretical and practical issues that stimulated subsequent research programs, such as one that looked at the problem of how to organize for virtual teaming and another that looked at the learning processes entailed in a shift from hierarchical to lateral work processes.

FIGURE 3.2 A Recursive Sequence of Programs in the Organization Design Research at CEO

The next section examines our knowledge work teams research program with special attention to the research collaborations that composed it and how collaboration was built. We then take a deeper dive examining the elements of one highly successful collaboration.

Collaboration in a Knowledge Work Teams Research Program

The KWT research program lasted for five years, and its purpose was to gain knowledge useful to the design of effective team-based work systems in knowledge work settings. Our initial step was to convene a “special interest group workshop” of companies interested in talking about their experiences with knowledge work teams and creating a research agenda. That meeting led first to a ten-month collaboration with the Hewlett-Packard Corporation (HP) and to subsequent collaborations with nine other companies.

1. The HP research project was collaborative. The research team consisted of four academics from CEO and four members of the Strategic Change Services (SCS) group at HP. Our HP collaborators were focused on learning how to design effective new product development teams to speed time to market. The use of cross-functional teams for this purpose was new to the company. It was proving more difficult than anticipated to become effective at this work design in the research and development (R&D) part of the company, despite the company’s impressive success using team designs in factories.

This study used a grounded research approach to understand teaming in knowledge-work settings (Glaser & Strauss, 1967). We took into account existing theories of teams that had been developed mostly in production and back office settings, although we knew from our special interest group meeting that companies were having trouble applying these theories effectively. We also built on theories of work design and technology. We conducted structured interviews with approximately 15 managers, team leaders, and members in a succession of ten HP product divisions. After each set of division-specific interviews, two members of the research team coded the themes; then the entire research team met to interpret the findings and make refinements to our working models as we became aware of salient elements in each setting. Through the succession of ten cases, the design team generated theory and a foundational design model for highly interdependent knowledge work.

One test of this model was through action research in the participating HP divisions. The HP collaborators turned the learnings from the study into an intervention tool, worked with the redesign processes in many HP divisions, systematically assessed the impact of changes, and developed a dissemination strategy so that divisions across HP became aware of and started to use the design model.

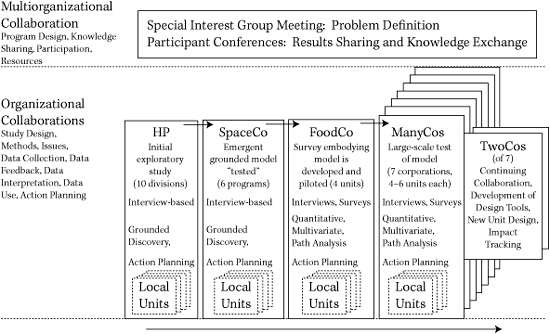

Through the collaboration with HP it had become clear that the difficulty companies were having building effective knowledge work teams stemmed from the ambiguity of authority in these cross-functional structures, the dynamic contexts in which they operated, and the extreme interdependence in these settings. They needed features to deal with each of these contextual realities. Subsequent collaborations with other companies built on, tested, and extended this understanding and contributed to more generalizable theory and to enriched models of knowledge-work teaming. These collaborations, illustrated in Figure 3.3, included the following:

2. The replication of the exploratory HP study in a corporation that had a very different business model and employed different technologies. There we studied teams designing large electronic and information technology (IT) systems. We enlarged our focus to deal with the integration between multiple interdependent teams involving as many as hundreds of engineers, scientists, technicians, and analysts. Through this second collaborative study we further elaborated our theory and models and started conceptualizing the design features of business units (such as electronics programs) that operated with a cross-functional team-based work design.

3. A third collaboration included developing a survey instrument to measure the theoretical constructs and field testing it in a corporation that employed cross-functional teams to research and develop innovative consumer foods products. The line management sponsors in this setting wanted to understand how to increase the effectiveness of these cross-functional teams. They were interested in a diagnostic tool that would help them determine causes of team dysfunctions and underperformance.

4. Seven other companies collaborated to improve and validate the survey and the theory-based team model in companies with different kinds of teams and technologies. Their agenda was to learn a new framework, but also to gain a tool—a diagnostic survey.

5. Two of the seven companies in step 4 continued on with a formal redesign of their team-based work systems based on the findings from the diagnostic surveys. We worked with them to carry out systematic assessment and iterative design, thereby developing a more nuanced understanding of how theoretical concepts worked in practice.

During the three years of these studies, periodic conferences were held for the participating companies, in which current results were shared and discussed. Companies and academics shared perspectives and interpretations of study findings and of what the companies were changing and learning in their companies about how to make their teams more effective. The systematic findings from the research were only one input into wide-ranging discussions that focused primarily on the knowledge and experience of practice. These sessions were important for the CEO researchers in understanding the contexts in which the research is used (or not) and in further understanding the actual challenges of practice.

Various academic- and practitioner-oriented articles, chapters, and presentations were generated along the way. At the end of the program of the collaborations, when we felt confident in the overall model that had been generated, the cumulative results of the research program were published in a book (Mohrman, Cohen, & Mohrman, 1995) aimed at a mixed audience of academics and practitioners. We quickly received feedback from some of our company collaborators that a 389-page book was not viewed by many practitioners as a particularly useful product. These collaborators had found participation in the study and the study findings useful in helping them to make changes in the design of their knowledge work teams that contributed to more effective performance. Yet we still faced the challenge of how to “package” learnings from this study to make them broadly accessible and compelling to the managers in their organizations. This need led to an additional collaboration:

FIGURE 3.3 Multilevel Collaboration in the Recursive Knowledge Work Team Program Studies

6. Two of the participating companies collaborated in the creation of a design workbook that placed the findings from the research study into a practical design tool (Mohrman & Mohrman, 1997). Representatives of these companies worked with us to think through the parameters that should characterize a useful design tool. Ideally they wanted a tool that could be used by line managers independently once they understood the model. To help do this, an instructional designer was brought into the team. This person brought graphic design ideas and was an expert in the visualization of complex information—skills none of the academic research team possessed. Both collaborating companies provided several beta sites—units that were redesigning or being formed anew. The unit managers used a draft of the workbook with the design team and provided feedback on how to change and improve the tool.

The HP Collaboration—The Knowledge Combination Process

The first study (with HP) in the KWT research program illustrates some key elements of a highly successful collaboration from the perspective of the different involved stakeholders. This collaboration is described in greater detail elsewhere (Mohrman et al., 2007). In this chapter, we will focus on the knowledge contributions and roles of members of the different communities of practice in the research, alignment and differentiation of purpose and interests, and the unfolding of the collaborative relationship through time.

The four members of HP’s SCS group who were our direct collaborators were experienced internal organizational effectiveness consultants. Several had specialized in the design and implementation of high-involvement factory work systems. Thus, although representing two different communities of practice (academic researchers and company-based organizational consultants), there was considerable overlap in knowledge bases, and purposes were readily aligned. Both were concerned with extending existing knowledge to contribute to the design of innovative organizational approaches to address important organizational problems. The groups shared common values on business, technical, and social features and outcomes that were inherent in the sociotechnical systems models that had underpinned the practical work at HP and had been the focus on some of the previous CEO research.

The head of this group, Stu Winby, saw the collaboration with USC as the first test of a new way of operating for his group. His vision was that SCS would partner with academic researchers to yield knowledge that would become embodied in the capabilities of HP through the SCS’s development of models, frameworks, and tools to help HP achieve a competitive advantage (Kaplan, 2000; Kaplan & Winby, 1999). In Stu’s words, “In many ways the SCS mission was similar to the USC-CEO mission. We had action research as the core and base of all our operations. Sharing a similar mission from external and internal perspectives made the outcomes all the more robust” (Mohrman et al., 2007).

The study team exchanged and iterated articles and working documents and had several teleconferences in which the members described our goals for the study and shared ideas about how these might be accomplished. We then spent a day together, agreeing on purpose and on a high-level research design. The purposes were to learn from the nascent product development teaming efforts in the corporation about the following areas:

![]() the nature of knowledge work teaming

the nature of knowledge work teaming

![]() how knowledge work teaming differs from factory floor teaming

how knowledge work teaming differs from factory floor teaming

![]() what design features influence the effectiveness of knowledge teams in accomplishing business, customer, and employee outcomes

what design features influence the effectiveness of knowledge teams in accomplishing business, customer, and employee outcomes

![]() how existing models of team systems and existing intervention models need to change to reflect the knowledge that is developed

how existing models of team systems and existing intervention models need to change to reflect the knowledge that is developed

Nested within the overall CEO/HP collaboration were a series of local collaborations that brought in a third community of practice: the managers and team leaders who were trying to use cross-functional new product development teams as a business tool. A study team was set up in each participating division to help shape the micro design of the study at the local level and articulate local goals and questions for the study. This local team also interpreted the data patterns that emerged from the study and identified action implications. The study teams at the local level minimally included the general manager, key functional managers, and several team leaders.

The common problem aligned the interests of the divisional leaders with the research. They were interested in understanding and redesigning their new product development teams to be more effective. Their focus on action aligned with our belief that the test of the knowledge in practice happens through a design process in which the new design is socially constructed by the participants.

CEO members saw this collaboration as a first step in creating a robust theory and a model of knowledge teams that could become part of the academic and practitioner literatures, and a design model for knowledge teams that could be employed by many organizations. The goal for the HP’s SCS members was to create a grounded, substantive model to guide team transitions and redesigns at HP, to test the model through their various consulting interventions, and to “productize” the model and the design intervention process so that it could more easily diffuse throughout the organization (Kaplan & Winby, 1999). HP’s intervention models and the working model for knowledge teams that the CEO researchers wrote up and carried forward into next studies were variants of the same knowledge base that was created through the collaboration and in particular through collaborative interpretation of the data patterns. Both understood the results through the lens of their roles, values, and goals, and encoded the resulting knowledge in formats that fit their communities of practice and contributed to the intended trajectory of their professional activities.

CEO’s knowledge work teams research program further developed the programmatic approach that we had used with the earlier performance management studies. With interested companies we identified a broad problem and moved through a series of studies and addressed the various stages of knowledge creation. This process started with the identification of a problem and moved from exploratory research to theory generation and testing, model creation, and the testing of the knowledge through action research. In both the performance management program and the knowledge work teams program, the initial grounded work was enabled through collaboration with a large corporation with internal organizational effectiveness units comfortable with research and interested in the opportunity to work with academic researchers to generate knowledge. These initial collaborations yielded a baseline theory and design model that attracted additional companies to replicate, extend, and then test the model through systematic evaluation research. Throughout the process, we published the incremental knowledge for both communities, in both cases finally “packaging” the combined knowledge in books aimed at the dual communities of research and practice (Mohrman, Cohen, & Mohrman, 1995; Mohrman et al., 1989).

HP would collaborate with CEO in two more research studies during the next decade—one focusing on the acceleration of fundamental changes in organization designs and the other on the design features for effective virtual teaming. Many companies in CEO’s network of sponsors and collaborators were experiencing problems in these areas—a fact that led CEO to initiate multicompany research programs. Both communities of practice were attending to the same unfolding environmental, organizational, and competitive dynamics that were reshaping organizations. Organizational practitioners in companies around the world were, through experience and design, developing knowledge and approaches to deal with these forces. Academic knowledge was also being generated in universities and research groups globally. These were the knowledge bases we brought together in collaborative problem-oriented research.

Recursive Research Programs

By 1995, CEO’s KWT research team had worked intensely together for six years. Through our experiences studying the ten companies, we subsequently became interested, collectively and individually, in related problems that emerged from the team study. We pursued these questions in subsequent collaborative research programs (see Figure 3.2). Susan Cohen teamed with Cris Gibson to conduct longitudinal, multicompany, collaborative studies of the features and dynamics of virtual teams, which were becoming more and more prevalent and added layers of complexity to the challenge of designing effective teams (Gibson & Cohen, 2003). This was followed by a series of studies of virtual teaming across company boundaries (Mankin & Cohen, 2004).

Mohrman and Mohrman sequentially pursued two multistudy, multicompany research programs that stemmed directly from the theoretical and practical challenges encountered during the knowledge work teams program. The first included academic colleague Ram Tenkasi and ten companies to explore the change and learning challenges companies were confronting as they moved from the functional, hierarchical designs to cross-functional, lateral organizations (Tenkasi, Mohrman, & Mohrman, 1998). The purpose of the participating companies was to learn how to accelerate such changes. The second research program was a collaboration with academic colleagues David Finegold and Jan Klein and nine companies to examine design approaches to address the competing tensions faced by technical firms as they try to maintain cutting-edge technical capability while using cross-functional teaming to meet performance pressures (Mohrman, Klein, & Finegold, 2003; Mohrman, Mohrman, & Finegold, 2003). The purpose of the companies was to understand how to operate cross-functionally yet continually extend their discipline and functional capabilities. The purpose of the academic researchers was to understand how organizations build the capacity to manage these multiple focuses that establish apparently conflicting interests in the organization.

Both these multiple company studies were longitudinal in nature, allowing us to examine the dynamics and impacts of change over time. Because we often did not have the good fortune to work with internal researcher-consultants as we had in the HP example, we developed a permutation of our approach; in some companies, a member of the academic research team worked closely as a participant collaborator in the company’s action research process, while the others focused on the systematic longitudinal data gathering and analysis.

Studying Our Collaborative Research Process: The Importance of Relating to Internal Design Processes

To gain insight into whether and how collaborative research is useful to organizations, Chris Gibson, who was then a newly arrived researcher at CEO, teamed with us to craft a retrospective study of the ten companies that had participated in the research program aimed at generating knowledge about how to accelerate organization design transitions. The study was based on previous theory about how different communities are able to incorporate each other’s knowledge to yield changes in the way they practice (Boland & Tenkasi, 1995; Tenkasi & Mohrman, 1999). The data were gathered using a structured interview methodology, coded and analyzed, and interpreted by two researchers who had not been involved in the original research nor in any of the previous CEO collaborative research programs.

This investigation (Mohrman, Gibson, & Mohrman, 2001) in our view confirmed the suitability of collaborative research with a design perspective to yield useful knowledge. Whether these companies viewed the research as having been useful related to whether they actually used the findings. Did they incorporate the findings into their internal sense-making and organizational design processes? Did they make changes to their organization taking the findings into account? Usefulness also related to whether the company participants experienced the researchers as having incorporated the perspective of practice into the research and to whether time had been spent mutually interpreting the data patterns. Interestingly, usefulness was not related to practitioner involvement in the design and conduct of the research. This finding suggests that the usefulness of research knowledge does not depend on turning practitioners into researchers. It depends on bridging the meaning gap and generating knowledge that can be contextualized by the organization to inform changes in the way they operate.

The onus of usefulness is not only on the academic researcher. Usefulness depends on the members of the company engaging in the hard and intentional work of applying the knowledge to make changes in how they function. In the HP example, the SCS group’s role was to create tools and interventions to make this possible. It produced models that were disseminated and became widely available to guide line managers and organizational effectiveness professionals leading and working with many HP units moving toward team-based designs. According to their leader, Stu Winby:

What we discovered about ways of organizing and the artifacts we developed were helpful to people in conceptualizing what they were about. Years later I saw the models out on managers’ desks. People don’t understand the impact because it’s all tacit. We formalized all that into a model that could be used in consulting, not just by our group, but by many others in the organization. (Winby in Mohrman et al., 2007, p. 523)

The SCS group used the project with CEO to hone its approach to contribute value to HP, including finding ways to disseminate the learnings from the project more broadly. The group was aware from experience that successful design innovations do not diffuse easily. They sponsored a series of Work Innovation Network (WIN) meetings, where line managers and various other groups came together to hear about the experience of HP units that had used the models to redesign. The sessions were used to talk with each other about what is required and what would lead to improvements in the model and to have participants leave with both contacts and awareness of how they could utilize this knowledge locally. Winby reflects on the role of the WIN meetings:

We all read Dick Walton’s work that pointed out that you often do a new plant start up that is highly successful but never diffuses anywhere else in the company. We hired a person who started working on diffusion approaches and we developed a model for diffusing work innovations. The principle was to develop a pull system rather than rely on pushing the innovation out. Get the line managers to present their results at our Work Innovation Meeting, which became the distribution and marketing arm of the model. We would do the work with the customer and measure the results and even if it was a failure it was presented at the WIN meeting—the General Manager and another manager from the division and one of our group would stand up and present what happened. It was videotaped and shared beyond even the attendees. People from other businesses would come up and say, “Can I do that? Can I send someone to your business to learn?” This often provided next generation projects so that the learning could be extended to new areas. (Winby in Mohrman et al., 2007, p. 523)

This example illustrates the challenge and extent of multistakeholder involvement required for knowledge to be turned into changed practice. Conversely, it illustrates how easy it would be for even the most collaborative of research to lead to no change, if the companies do not put in place the processes for learning and change.

Challenges and Future Approaches in Design Research

Organization sciences face major hurdles in meeting the demands of rigorous science. In following the tenets of rigorous positivistic science, these disciplines also face major barriers to relevance to organizations. In our view, the hurdles of science and relevance converge. We believe that a programmatic collaborative organizational design research approach, while not solving these problems completely, addresses some of these challenges.

One science challenge is examining enough instances of a phenomenon to be able to draw inferences that seem valid and reliable from instance to instance—the challenge of generalizability. Practitioners sense this same shortcoming and feel a lack of confidence that the patterns of academic findings are relevant to them in their context facing their particular set of performance challenges. Collaboratively examining issues with multiple companies, methodologies, and from multiple perspectives helps address the problems of generalizability and contextual variability.

Another science challenge is executing longitudinal and predictive research designs to increase confidence in the value of the knowledge to people and organizations to help address their problems and become more effective. Alternating descriptive and predictive research (Chatman, 2005) helps deal with the need for rigorous knowledge and predictive power and begins to bridge the gap between the theory-driven world of academia and the context and results-driven world of organizational practice.

The complexity of organizational systems, in terms of both the number of elements, actors, and relationships and their dynamic nature, poses a challenge for researchers, whose methodologies have only slowly evolved to be able to deal with complex systems. There is a mismatch between methodologies and the reality of complex organizational contexts; the former demand control and can only handle a narrow range of variables, and the latter does not afford practitioners the luxury of analytically separating out its parts when making decisions about how to operate. Practitioners look for tools and interventions that make a difference in solving problems—actionable approaches that do not come couched in terms of variables and causal relationships abstracted from practice. Research programs that include action components by necessity place knowledge squarely into the complex world of practice.

Collaborative, programmatic, design research approaches only partially deal with these challenges. We know from our own research that even the participants in such studies only sometimes apply the knowledge that is generated. Furthermore, many of the companies in our CEO network and beyond are increasingly resistant to time-consuming research to solve problems that they are struggling with right now. They seek the holy grail of tested “best practices” believed to be effective in other companies viewed as successful and able to be quickly and readily implemented.

Yet the need for research is evident. Organizations face no shortage of challenges and pressures to change their practices to be successful in areas that are poorly understood. Today’s fast-paced environment is characterized by unprecedented levels of global interdependence and the ongoing reconfiguration of players, strategies, capabilities, and resources. The problems companies confront are increasingly complex and urgent. If the organizational sciences are to be useful in such an environment, then there must be increased speed, greater incorporation into research processes of the problems of organizational practice, and the ability to deal with increased complexity through greater multidisciplinarity in our research approaches.

We feel confident that collaborative design research is an approach that promotes usefulness. Yet we know that this potential will not be achieved if we do not enhance our capabilities to conduct research more quickly and in a way that addresses the changing realities faced by organizations. At CEO we are working on ways to create parallelism in erstwhile time-consuming, sequential research processes. We are creating broader and more diverse networks of collaborators loosely configured to simultaneously bring multiple methods and theories together to focus on a common problem. One such problem that we are addressing is how to elevate contribution to societal and ecological sustainability to be core organizational focuses and primary outcomes. We are building a collaborative research network with diverse stakeholders including the knowledge bases needed to accelerate the conduct of research and the sharing of ideas and findings. In this way we hope to break down the sometimes competitive silos between researchers and to combine the knowledge of multidisciplinary research and organizational practice. Such a network of collaborators ideally will collectively and quickly detect, examine, catalyze, and study changes in organizing practices.

This goal is lofty and the challenges are immense. These include the complexity of the substantive challenges being investigated—of organizing for new purposes and in new ways. Perhaps most challenging, however, are the process elements of building the research network in new ways. Only by innovating our organizational research practices can we hope that research knowledge will be relevant to the organizations we study and with whom we collaborate—and to the immense organizing challenges in today’s world.

We at CEO are definitely not alone in advocating the need for such changes in how we operate. The proposed tenets of “engaged research,” beautifully developed by Van de Ven (2007), are similar to our approach. Engaged research is also aimed at collaborating to solve important problems. In effect, organizational researchers are facing the very same challenges faced by the organizations we study in this dynamic and complex environment. We have to change the way we operate to reflect and address the changing context in which we are trying to add value.

REFERENCES

Argyris, C. (1996). Actionable knowledge: Design causality in the service of consequential theory. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 32, 390–406.

Boland, R. J., & Tenkasi, R. V. (1995). Perspective making and perspective taking in communities of knowing. Organization Science, 6(4), 350–437.

Campbell, D. T., & Stanley, J. C. (1963). Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for research. Chicago: Rand McNally & Co.

Chatman, J. (2005). Full-cycle micro-organizational behavior research. Organization Science. 16(4), 434–447.

Eden, C., & Huxham, C. (1996). Action research for the study of organizations. In S. Clegg, C. Hardy, & W. R. Nords (Eds.), Handbook of organizational studies (pp. 526–542). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Elden, M., & Chisholm, R. F. (1993). Features of emerging action research. Human Relations, 46(2), 121–142.

Galbraith, J. R. (1994). Competing with the lateral, flexible, organization. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Ghoshal, S. (2005). Bad management theories are destroying good management practices. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 4(1), 75–91.

Gibson, C., & Cohen, S. (2003). Virtual teams that work: Creating conditions for virtual team effectiveness. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory. Hawthorne, NY: Aldine.

Huber, G. P., & Glick, W. H. (Eds). (1993). Organizational change and redesign: Ideas and insights for improving performance. New York: Oxford Press.

Kaplan, S. (2000). Innovating professional services. Consulting to management, 11(1), 30–34.

Kaplan, S., & Winby, S. (1999). Knowledge asset innovation at Hewlett Packard. Hewlett Packard Internal Working Paper.

Lawler, E. (1999). Challenging traditional research assumptions. In E. E. Lawler III, A. M. Mohrman Jr., S. A. Mohrman, G. E. Ledford, T. G. Cummings, & Associates (Eds.), Doing research that is useful for theory and practice (pp. 1–17). Lanham, MD: Lexington Books.

Lawler, E., Mohrman, A., Mohrman, S., Cummings, T., & Ledford, G. (Eds.). (1985). Doing research that is useful for theory and practice. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Lewin, K. (1951). Field theory in the social sciences. New York: Harper & Row.

Mankin, D., & Cohen, S. G. (2004). Business without boundaries: An action framework for collaborating across time, distance, organization and culture. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Mohrman, A. M., Jr., & Mohrman, S. A. (1998). Catalyzing organizational change and learning: The role of performance management. In S. A. Mohrman, J. R. Galbraith, E. E. Lawler III, & Associates (Eds.), Tomorrow’s organization: Crafting winning capabilities in a dynamic world (pp. 362–393). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Mohrman, A. M., Jr., & Mohrman, S. A. (2003). Self-designing a performance management system. In N. Adler, A. Shani, & A. Styhre (Eds.), Collaborative research in organizations: Leveraging academy-industry partnerships (pp. 313–333). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Mohrman, A. M., Jr., Mohrman, S. A., Lawler, E. E., & Ledford, G. E. (1999). Introduction. In E. E. Lawler III, A. M. Mohrman, Jr., S. A. Mohrman, G. E. Ledford, T. G. Cummings, & Associates (Eds.), Doing research that is useful for theory and practice (pp. ix–xlix). Lanham, MD: Lexington Books.

Mohrman, A. M., Jr., Resnick West, S., & Lawler, E. E. (1989). Designing performance appraisal systems. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Mohrman, S. A., Cohen, S. G., & Mohrman, A. M., Jr. (1995). Designing team-based organizations: New applications for knowledge work. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Mohrman, S. A., & Cummings, T. G. (1989). Self-designing organizations: Learning how to create high performance. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Mohrman, S. A., Galbraith, J. R., & Monge, P. (2006). Network attributes impacting the generation and flow of knowledge within and from the basic science community. In J. Hage and M. Meeus (Eds.), Innovation, science and industrial change: The handbook of research (pp. 196–216). London: Oxford University Press.

Mohrman, S. A., Gibson, C. B., & Mohrman, A. M., Jr. (2001). Doing research that is useful to practice. Academy of Management Journal, 44(2), 347–375.

Mohrman, S. A., Klein, J. A., & Finegold, D. (2003). Managing the global new product development network: A sense-making perspective. In C. Gibson & S. Cohen, (Eds.), Virtual teams that work: Creating conditions for virtual team effectiveness (pp. 37–58). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Mohrman, S. A., & Mohrman, A. M., Jr. (1997). Designing and leading team-based organizations: A workbook for organizational self-design. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Mohrman, S. A., Mohrman A. M., Jr., Cohen, S., & Winby, S. (2007). The collaborative learning cycle: Advancing theory and building practical design frameworks through collaboration. In A. B. Shani, S. A. Mohrman, W. A. Pasmore, B. Stymne, & N. Adler (Eds.), Handbook of collaborative management research (pp. 509–530). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Mohrman, S. A., Mohrman, A. M., Jr., & Finegold, D. (2003). An empirical model of the organization knowledge system in new product development firms. Journal of Engineering and Technology Management, 20(1–2), 7–38.

Mohrman, S. A., Mohrman, A. M., Jr., & Tenkasi, R. (1997). The discipline of organization design. In C. L. Cooper & S. E. Jackson (Eds.), Creating tomorrow’s organizations: A handbook for future research in organizational behavior (pp. 191–205). West Sussex, UK: Wiley.

Reason, P., & Bradbury, H. (2001). Handbook of action research: Participative inquiry and practice. London: Sage.

Romme, A.G.L. (2003). Making a difference: Organization as design. Organization Science, 14, 559–573.

Romme, A.G.L., & Endenburg, G. (2006). Construction principles and design rules in the case of circular design. Organization Science, 17, 287–297.

Schön, D. A. (1983). The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Seashore, S. L., Lawler, E. E., Mirvis, P. H., & Cammann, C. (Eds.). (1983). Assessing organizational change: A guide to methods, measures, and practices. New York: WileyInterscience.

Shani, A. B., Mohrman, S. A., Pasmore, W. A., Stymne, B., & Adler, N. (Eds.). (2007). Handbook of collaborative management research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Simon, H. A. (1969). The sciences of the artificial. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Stokes, D. E. (1997). Pasteur’s quadrant: Basic science and technological innovation. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press.

Tenkasi, R. V., & Mohrman, S. A. (1999). Global change as contextual collaborative knowledge creation. In D. L. Cooperrider & J. E. Dutton (Eds.), Organizational dimensions of global change: No limits to cooperation (Human dimensions of global change) (pp. 114–136). Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

Tenkasi, R. V., Mohrman S. A., & Mohrman, A. M., Jr. (1998). Accelerating learning during transition. In S. A. Mohrman, J. R. Galbraith, E. E. Lawler III, & Associates (Eds.), Tomorrow’s organization: Crafting winning capabilities in a dynamic world (pp. 330–361). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

van Aken, J. E. (2004). Management research based on the paradigm of the design sciences: The quest for field-tested and grounded technological rules. Journal of Management Studies, 41, 219–246.

van Aken, J. E. (2005). Management research as a design science: Articulating the research products of mode 2 knowledge production in management. British Journal of Management, 16, 19–36.

Van de Ven, A. H. (2007). Engaged scholarship: A guide for organizational and social research. New York: Oxford University Press.

Weick, K. (2003). Theory and practice in the real world. In H. Tsoukas & C. Knudsen (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of organization theory: Meta-theoretical perspective (pp. 453–475). New York: Oxford University Press.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Susan Albers Mohrman is senior research scientist at the Center for Effective Organizations (CEO) in the Marshall School of Business at the University of Southern California. Her research and publications focus on organizational design for lateral integration and flexibility, networks in basic science, design for sustainable effectiveness, organizational change and implementation, and research methodologies for bridging theory and practice. She is co-founder and a faculty director of CEO’s certificate program in organization design. In the area of useful research, she is an editor and author of the Handbook of Collaborative Management Research (2007).

Allan M. Mohrman Jr. is a founding member of the Center for Effective Organizations (CEO) in the Marshall School of Business at the University of Southern California. His research and publications focus on performance management, organization design, team-based organizations, and research methodologies that bridge theory and practice.