NINE

On Knowing and Doing

A Perspective on the Synergies between Research and Practice*

The Challenge of Knowing and Doing: A Personal Context

My career has been one of deliberately linking research (knowing) and practice (doing). As an undergraduate student at Northeastern University, I worked for five years as a co-op student at General Radio. This distinguished electronics firm was one of the first of its kind and was, at the time, the leading test equipment firm in the industry. However, during this period, the company began to fail in the face of technological change and the entrance of new competition (HP, among others). My carpool friends were about to be laid off. They faced the trauma associated with a historically dominant firm floundering in the face of a rapidly shifting competitive arena. As it turned out, making the same products better simply drove the firm more quickly out of business. I observed General Radio’s inertial responses to these competitive shifts and the disastrous consequences for its employees and stakeholders.

These experiences at General Radio led me to leave an electrical engineering career and move to graduate school to try to understand just what happened. For 30 years now, I have been working to answer the questions my carpool colleagues asked so many years ago. Just why do successful firms often fail at technological transitions? Why were seasoned executives rendered so incompetent at this particular transition? While my specific research questions have evolved over time, the central theme of my research has been rooted in this General Radio experience; that is, on trying to better understand how and why firms fail to adapt in the context of technological transitions.

After Northeastern, I went to graduate school at Cornell University. At the School of Industrial and Labor Relations, I worked with a heterogeneous faculty committee (William F. Whyte, Leo Gruenfeld, and Mike Beer). While these colleagues could not have been more different as scholars, they were each interested in research shaping the real world. My master’s thesis on leadership and change in a Corning manufacturing plant built on the extant literature on change. But it was also substantially informed by emergent political and cultural issues I observed in the field (Tushman, 1978). This experience illustrated the benefits of a close relationship between the world of research and the world of practice. The phenomena taught me to look in places and at questions that were not central to the field at the time. I also experienced issues and tensions that occur at this boundary between knowing and doing. For example, early in my fieldwork, I was pressed by the plant general manager to shape my research to his needs and to provide him with inside information gained from my interviews. My committee helped me sort through these boundary issues associated with the locus of data and research question ownership.

Because of my interest in technology, innovation, and organizations, I left Cornell and enrolled in a PhD program at MIT. Working with another heterogeneous faculty committee (Tom Allen, Paul Lawrence, Ed Schein, and Ralph Katz), I replicated this work at the interface between the phenomena and research.1 My dissertation explored the relations between informal communication networks and performance in research and development (R&D) settings. I gathered network data from Owens Corning and was able to show that differential performance in R&D teams was associated with communication networks that were contingent on task characteristics (e.g., Katz & Tushman, 1979; Tushman, 1977). While the research was well received academically, I was challenged by several R&D managers to translate my research in a way that might be useful to them. I was further challenged by these managers to broaden my work from simply studying R&D settings. These managers observed that if I was really interested in understanding innovation, understanding R&D settings was insufficient. They pushed me to move from the R&D laboratory to the organization as the unit of analysis.

These early experiences made clear the benefits (as well as challenges) of having the phenomena shape the questions I asked and the data I gathered. Over the past 30 years I have, with colleagues and doctoral students, worked at the interface between research and practice; more specifically, between building our field’s stock of knowledge of innovation and organizational change, and accentuating our field’s impact on practice. I have been working out my own research-based responses to my carpool friends and to those R&D managers who challenged me to link our field’s research to their real world innovation issues.

In distinct contrast to this active linking between research (knowing) and practice (doing), our field has been drifting toward a greater bifurcation. Knowing has increasingly been uncoupled from doing. This increasing gap is problematic. It has the potential to push our research to greater internal validity at the cost of stunting external validity. Our field runs the risk of having great answers to less and less interesting problems. As our field retreats from managerial relevance, other disciplines and professions move into that vacuum (Bazerman, 2005; Bennis & O’Toole, 2005; Pfeffer & Fong, 2002). This lack of coupling between our research and our ability to speak to practice affects our legitimacy with students and our external constituencies (see also Khurana, Nohria, & Prenrice, 2005; Rynes, Bartunek, & Daft, 2001). Further, this bifurcation affects both what and how we train doctoral students (e.g., Polzer et al., 2009; Tushman & O’Reilly, 2007).

Business Schools: Toward Knowing and Doing

To fairly evaluate the relative importance of business schools’ research and impact on practice, we must first be clear about the role of professional schools in general and business schools in particular. What, if anything, differentiates a business school (or school of medicine or law) from conventional academic departments? To understand these differences, we draw on insights from the history of science where there has long been a tension between “basic” and “applied” research (Stokes, 1997).

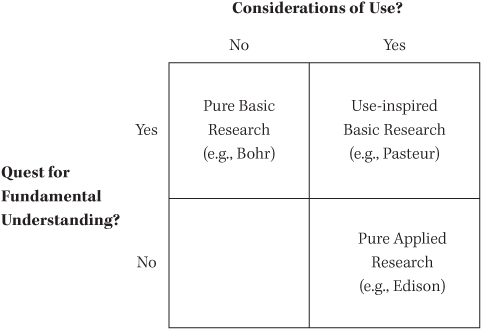

In his book Pasteur’s Quadrant (1997), Donald Stokes draws on the history of science in general and Louis Pasteur’s contribution in particular to develop a taxonomy of types of research (see Fig. 9.1). In this framework, research is categorized in three ways: (1) as a quest for fundamental understanding (basic research), (2) as development of knowledge motivated by considerations of use (applied research), or (3) both. Stokes shows how some research is simply driven by a quest for understanding with no thought of specific use (e.g., Niels Bohr and the discovery of the structure of the atom). Other research can be undertaken simply to develop applied uses (e.g., Thomas Edison and the invention of the phonograph). Yet other research, which Stokes favors, proceeds with both a quest for fundamental understanding and a desire to apply the findings (e.g., Pasteur and the development of microbiology).

FIGURE 9.1 Stokes’s Quadrant Model of Scientific Research

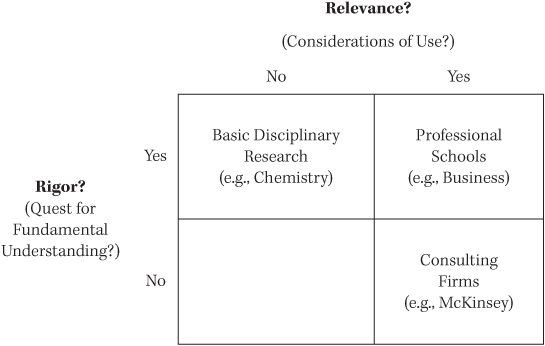

Stokes’s (1997) classification scheme can be used to inform the debate on the aspirations of business school research (see Fig. 9.2). Whereas conventional academic disciplines are typically about a quest for understanding (rigor) with little thought of use (relevance), business schools and professional schools, more generally, are about both; that is, about operating in Pasteur’s Quadrant. Consulting firms, unlike business schools, are about meeting clients’ needs (relevance) but have little concern with carefully controlled research (rigor). The implication of this taxonomy for business schools is straightforward. In business schools, research should be judged both by its quality—how rigorously it is designed and conducted—as well as the degree to which it provides understanding of the phenomena being studied. Stokes refers to this as “purposive basic research” (1997, p. 60) and observes that this research can be highly fundamental in character when it has an important impact on the structure or outlook of a field (e.g., Porter’s work on competitive strategy, Bazerman’s work on decision making and systematic deviations from rationality, or Kaplan’s work on activity-based accounting). Basic research and applied research are not mutually exclusive undertakings.

Consistent with Mintzberg’s (2004) and Bennis and O’Toole’s (2005) call for relevance and rigor, and Ghoshal’s (2005) plea for faculty research that respects discovery-driven research as well as integrative- and application-oriented research, Stokes’s framework imposes high standards on faculty in professional schools. Whereas the evaluation of rigor is straightforward in traditional academic domains (Does the research meet the standards of peer review?), the evaluation of professional school research is more complex in that this assessment must attend to both academic rigor as well as managerial relevance. In the business school context, this implies that our research must meet the joint criteria of internal as well as external validity. Further, Stokes’s insights have implications for doctoral training. Doctoral students need to have their research questions anchored on the phenomena even as they explore questions through systematic multidisciplinary training (e.g., Polzer et al., 2009).

FIGURE 9.2 Business School Research

A Point of View on Knowing and Doing

My early research experiences at Corning and Owens Corning illustrated the benefits and challenges associated with research informed by conversations with the phenomena. Encouraged by my faculty advisors to work at this boundary, I have evolved an implicit model on the co-evolution of knowing and doing. These knowing-doing relationships have had an important effect on my research as well as my MBA, executive, and doctoral teaching (see also Adler et al., 2009; Tushman et al., 2007). Although these experiences are idiosyncratic to me, my students, and my colleagues, they may have broader implications.

Over the past 30 years, I have experimented with several executive education program designs with colleagues at Columbia, INSEAD, Stanford, and Harvard (most intensively with Jeff Pfeffer and Charles O’Reilly). These alternative designs have had important impacts on our research streams as well as on our ability to affect practice. Our early, more traditional, executive education designs were loaded with content; faculty delivered their material over a five-day program. We quickly received feedback that while the content was of interest, participants wanted to link our field’s researched-based knowledge to their own unique innovation, leadership, and change issues. In response to this request, we built in more application work and began to encourage intact teams to come to campus to work their issues throughout the program. We encouraged both intra as well as inter team sharing and collaboration. These active linkings between knowing and doing were highly valued by participants even as we learned more about the relevance of our research. Further, these more engaged relationships brought us closer to those leadership, innovation, and change issues where our field’s research had little to say. For example, my research on the consequences of total quality management (TQM) on innovation outcomes (e.g., Benner & Tushman, 2002, 2003) was directly rooted in contentious conversations with executive education participants from Alcoa.

More recently, O’Reilly and I have developed both custom and open executive programs for senior teams. Senior teams come to campus for three or more days to work their specific innovation and change issues. Faculty content is tailored to a particular firm and its particular issues. Roughly half the time is spent in content sessions; the other half is spent in facilitated teams linking faculty content to their specific issues. These action-oriented, senior team executive programs provided a context where we were able to sharpen and extend our research questions, improve our access to the field, and directly link research to practice.

The most extensive and sophisticated action-learning version of our executive education work has been with IBM. Under the sponsorship of Bruce Harreld, IBM’s senior vice president of strategy, we have collaborated over a five-year period on strategic leadership forums (SLFs). Although we learned how to construct these workshops over time, the fundamental design of intact senior teams sponsored by a corporate executive was set. The senior sponsor commissioned the scope of the work, chose the teams, and agreed to sponsor the outcomes associated with the workshop. The SLFs often had a corporate or line-of-business issue as a theme (e.g., cross line of business innovation or developing emerging business opportunities).

For these IBM SLFs, senior teams came to campus for three days armed with prework and a preliminary performance or opportunity gap articulated by the senior sponsor and general manager. During an SLF, faculty present and link content to cases for roughly half the SLF. The rest of the time is in facilitated workshops where intact teams directly link classroom material to their specific managerial challenge. Teams present their diagnostic work and their implementation plans to each other. There is much learning in the feedback sessions in which each team gets feedback from the other teams on the depth and quality of their diagnostic and change work. Over this three-day workshop, teams and their leaders gained substantial consensus on root causes, action plans, and next steps. Not only do the feedback sessions help individual teams with their strategic issues, but listening to multiple teams helped senior executives induce IBM-wide issues relating to innovation and change. Senior IBM executives initiated each workshop, participated for the three days, and were, in turn, actively involved in following up on work initiated at these workshops.

In return for this long-term faculty involvement, IBM’s senior leadership provided support and access for faculty and PhD student research projects. For example, dissertation research by Benner, Smith, and Kleinbaum all had their roots in these collaborative executive education relationships (e.g., Benner & Tushman, 2003; Kleinbaum & Tushman, 2007; Smith & Tushman, 2005). Similarly, my work with O’Reilly has been shaped by these relationships (e.g., Harreld, O’Reilly, & Tushman, 2007; O’Reilly, Harreld, & Tushman, 2009; Tushman et al., 2007). Although these research projects were distinct from our executive education work, the results of the research were reported in subsequent SLFs. We have replicated these senior team–action learning relationships with a range of firms including BOC, the United States Postal Service, Siebel Systems, Irving Oil, and Agilent Technologies.

For example, during this custom program relationship with Harvard Business School (HBS), IBM had initiated a corporate strategy of simultaneously competing in multiple time horizons. As we worked in our custom programs sessions, it quickly became clear that these executives were searching for organization architectures that could exploit and explore both within business units and across the corporation. They were also grappling with the characteristics of those senior teams that could handle the contradictions associated with competing in different time frames. These observations and resulting conversations led directly to data collection on organization design choices and innovation (e.g., O’Reilly, Harreld, & Tushman, 2009; Tushman, Smith, Wood, Westerman, & O’Reilly, 2011), on interdependent innovation (Kleinbaum and Tushman, 2007), and on senior teams and contradiction (e.g., Smith & Tushman, 2005). With each of these phenomena-informed challenges, senior managers, doctoral students, and faculty developed research designs and data requirements that students were able to independently execute.

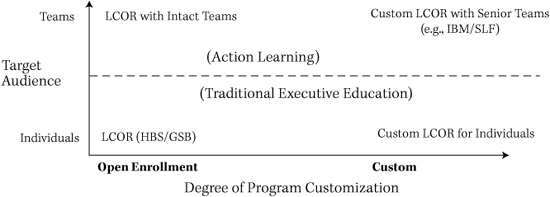

These senior team, action learning executive education designs facilitate a virtuous cycle between faculty and doctoral students collaborating with managers in research, and managers collaborating with faculty in shaping practice. The type of executive education design has had an important impact on our ability to shape practice and on the participants’ ability to inform as well as host our research. The more action oriented the program, the greater the quality of our relationship with these firms. In turn, the more senior teams trusted us, the more they understood our research agenda, the greater our ability to impact practice, and the greater their ability to connect with and help support our research and our students’ dissertations (see Fig. 9.3).

FIGURE 9.3 Experimenting in Executive Education Designs

Some Observations

1. Through executive education programs, I have been able to leverage our field’s research to influence practice. My most productive relations with executives are all rooted in using our field’s frameworks and literature to help solve real managerial issues.2 Because our field’s work adds substantial value to managers, relationships in executive education contexts open up the opportunity for faculty to learn what is managerially important but where our literature is silent. This ability to be taught what phenomena are important and then use these relationships to explore these phenomena is one of the great benefits of engaged scholarship (e.g., Van de Ven, 2007). Those most-productive knowing-doing relationships start with our adding value through researched-based insight (doing) and then moving to our research (knowing).

2. The more PhD students are involved in these executive education workshops, the more they interact with managers who are grappling with the phenomena, the more they understand the reality of innovation, leadership, and change.3 This deeper understanding leads, in turn, to well-anchored and insightful research questions (Lawrence, 1992). Although it is clearly not necessary to be in the field to induce important research questions, those doctoral students who know both the literature and the phenomena may be better equipped to ask relatively more provocative research questions. Finally, direct access to managers facilitates our students’ access to high-quality data (see also Tushman et al., 2007).

3. The longer relationship, the greater the trust and respect between managers and the researchers. The more faculty understand and respect the practitioners’ need for performance and the more practitioners understand and respect the faculty’s need to ask important research questions and gather reliable data, the more these relationships provide a setting for the co-production of knowledge and organizational impact.

4. These knowing-doing relationships affect our MBA, executive education, and PhD teaching. As executive education–research relations mature, we have been able to write cases, create leadership videos, and bring executives to class, as well as have executives host student field projects. Further, to the extent that our work with firms shapes those firms, we are more deeply informed on the phenomena we teach. These rich examples infuse and enliven our abilities as teachers.

5. The greater the action orientation of executive education programs, the greater the potential to develop relations such that our research and impact on practice are both enhanced. Executive education programs differ by degree of customization and the level of participant. The most action-oriented form of executive program we have employed is custom programs oriented to senior teams (see our discussion of the IBM custom program earlier in this chapter). These programs have been associated with the greatest impact on practice and with the greatest involvement of senior executives in our research questions, our data, and the interpretation of those data. It is in these action learning settings that we have co-produced action in these firms as well as co-produced innovative research (see Tushman et al., 2007).

Yet Some Concerns

With all the benefits of active collaboration between faculty and practitioners, there are also important boundary issues and areas of concern associated with these collaborations. These issues are rooted in the blurring of boundaries between the university’s independent pursuit of research and the firm’s local pursuit of practice: the possible distorting effects of faculty incentives in executive education programs, asymmetries in required skills and the associated need for faculty development and mentoring, and executive education administration in action-oriented executive programs.

1. Who owns the research question, who owns the data, who has access to the data, and who controls the interpretation, writing, and publication of the papers associated with these faculty-firm collaborations? Is it possible to test research questions in settings where the firm is buying executive education? These are all fundamentally important questions that get at roles and boundaries between universities and external organizations (e.g., Bok, 2003; Brief, 2000; Walsh et al., 2007).

In order for these engaged scholarship relationships to flourish, they must be rooted in the firm’s respect for independent faculty research. Independent research requires that faculty own the research question, the data associated with addressing the research question, as well as the decision where to publish the research (while protecting the firm’s confidentiality). Custom clients must understand that an important piece of the relationship with the business school is to support and encourage faculty research.

It is vital to have PhD students well integrated into these relationships between business schools and executive education clients. PhD students need to have access to custom program work on campus. These boundaries were tested several times. For example, a custom client balked when we asked that a PhD student sit in on our content sessions. We reiterated the importance of our research to the custom program client and our doctoral student’s centrality to this research. We observed that if the student could not sit in on the meeting, neither could the faculty. These misunderstandings were resolved in a fashion that clarified the synergistic relations between the firm’s need for confidentiality and impact and the faculty’s research requirements.

2. Another major boundary issue is the question of consulting on campus. To what extent is action learning the same as faculty consulting? Does action research on campus inappropriately use the university to host faculty consulting projects? While custom programs do have an action component, they are not consulting projects. Work on campus may be facilitated, but it is limited to the work on campus. Where faculty control the content in traditional executive education programs, they share control with custom clients in action-learning programs. Indeed one of the reasons that firms would use these modes of executive education is to get access to faculty research and the independence of faculty who have no vested interests as consultants. While relations on campus may well lead to subsequent consulting relationships (where the client has control of the questions and the pace of the relationship), these subsequent relationships are distinct from the faculty, PhD student, and executive education participant roles in on-campus programs.

3. For action-learning relationships to flourish, faculty must be willing to co-create these executive programs with the client firm. Custom programs inherently give more power to the client firm in both content delivered and program design. Further, faculty must be willing to teach for practice as they actively facilitate the linking of the program’s content to the participants’ specific needs. Further, faculty must be willing to teach not only their material but be prepared to make linkages across faculty content domains. This mode of teaching as well as program administration is more difficult than traditional executive education programs. The role of faculty director and program administration are much more client focused in these action-oriented custom programs. Faculty compensation models must be adjusted to account for the extra time involved in the teaching, facilitation, and design involved in action-learning programs.

4. Finally, faculty interest and skills in these active collaborations are not equally distributed. If these action-oriented executive education programs are to flourish, all faculty must be given the opportunity to work at the knowing-doing boundary. Issues of inequity of opportunity will dampen these boundary spanning experiments. As some senior faculty will be differentially capable of working these interfaces, they must take a proactive role in helping their senior and junior colleagues develop their integrative skills, their skills in translating research in ways that managers can understand, and their skills in actually helping managers solve real problems informed with our field’s research.

Executive Education as a Lever in Shaping Practice and Research

Given the reciprocal relations between knowing and doing as well as doing and knowing, executive education is of particular relevance to business schools and their faculty. Executive education is a setting where practitioners come to campus to make a connection between faculty research and their own managerial challenges. In these settings, there is an enhanced opportunity to forge long-term collaborative research-practice relations. Because these relationships develop on campus, they can be rooted both in research as well as in managerially anchored issues. Executive education settings are then a potentially important venue for developing engaged scholarship (Van de Ven, 2007; Van de Ven & Johnson, 2004).

Rigor and relevance, then, need not be separate but, rather, can be seen as interdependent activities in service of powerful theory and informed action (Huff, 2000; Weick, 2004). Action learning executive education workshops are one concrete way to embody this co-production of knowledge and practice. These enhanced individual learning and organizational outcomes are built on active collaboration between faculty and firms in program design as well as in linking program content to organizational outcomes. Through action learning workshops, we have been able to develop relations with a set of firms such that our field’s research has had a real impact on practice. Equally important, this interaction with practice has had a substantial impact on my research and that of my students, and has increased the quality of my teaching.

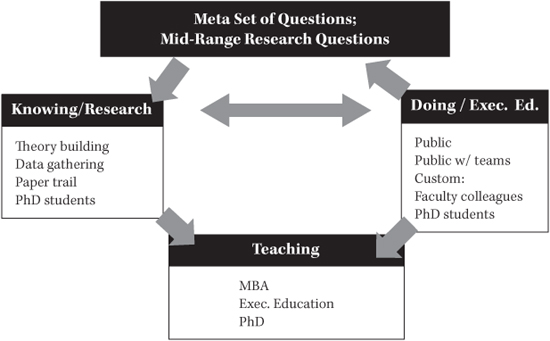

These relations between business schools and thoughtful firms have the potential to create virtuous cycles of knowing and doing (see Fig. 9.4). A meta research question anchored these cycles for me (e.g., What are relations between technical change and organizational evolution?) and hosted a range of more concrete research questions (e.g., What are the relations between competence-destroying change and executive team succession?). Our field knows much in these broad domains (Tushman, 2004). Executive education provides the setting where we can share this research with practitioners. In these educational settings we can make the knowing-doing link.

FIGURE 9.4 Knowing / Doing Cycles Affect Research, Practice, and Teaching

Relationships formed in action-learning settings, in turn, have shaped my research questions even as they have affected how I understand innovation and organizations. Doing has directly affected my knowing. Finally, both my action-learning work and my research directly affect the quality of my MBA, PhD, and traditional executive education work. As these business school–firm relations matured, the linkage between my research and practice become tighter and the co-production of research became more effective. Executive education workshops are contexts that help forge research-practice partnerships that permit these virtuous cycles to flourish (see also Kaplan, 1998, for a discussion of this virtuous cycle in the accounting and control area).

Yet business schools systematically underleverage executive education. At a time when firms are calling for more relevance and more customization, business schools remain in the modular, lecture-discussion format. While this traditional approach often is associated with participant satisfaction, the impact of these traditional executive programs on practice is equivocal (Anderson, 2003; Conger & Xin, 2000; Pfeffer & Fong, 2002). Further, since traditional executive programs do not encourage the development of relations between faculty and participants, the link to faculty research is stunted.

The concept of action-learning workshops, of active collaborations between business schools and firms, is generalizable. This action-learning approach requires clear and well-defined relationships and expectations. Faculty must take practice seriously and firms must take seriously supporting faculty research. This action-learning model is not new. It is similar to action-learning approaches hosted within firms (e.g., GE’s workout and IBM’s ACT; see Kuhn & Marsick, 2005; Tichy & Sherman, 1993; Ulrich, Kerr, & Asheknas, 2002). Other business schools are also leveraging executive education contexts for faculty research (e.g., MIT, Duke, LBS, INSEAD, IMD, among others). It is also similar to the consulting and executive education practices of a range of consulting firms (e.g., Argyris & Schon, 1996; Beer, 2001). What is different about action-learning workshops hosted within business schools is its emphasis generating powerful ideas and subjecting these ideas to rigorous inquiry. While consulting firms do generate powerful ideas, they are less equipped or motivated to subject these ideas to rigorous testing. Action-learning workshops position business schools to operate in Pasteur’s Quadrant; to be able to excel in both research-based insight as well as practical impact.

While action-learning workshops may be an underleveraged opportunity for business schools, there are important issues that these executive education designs raise. Action-learning designs raise issues on the appropriate boundary of business schools (Kaplan, 1998; Walsh et al., 2007). For research to flourish in action-learning relationships, faculty must own the research questions as well as the data gathered in service of these research questions. Bartunek (2002) observes that faculty must be in the firms, not of the firms. The extent to which faculty get co-opted by the sponsoring firm, the quality of the research will suffer (e.g., Bok, 2003; Brief, 2000; Hinings & Greenwood, 2002). Further, these action-learning workshops can not be confused with faculty consulting. Rather, action-learning workshops are co-created workshops, conducted on campus and managed by executive education staff. Faculty present content tailored to the client’s issues, teach to practice, and actively facilitate the linking of content to practice. Finally, these boundary spanning opportunities must be made available to all faculty who are interested in developing their skills to work at these interfaces. Issues of faculty inequity will assure that these experiments will fail.

While action-learning workshops are associated with a set of issues and concerns, they are a vehicle that has the promise to bridge the divide between our research and the world of practice, or between rigor and relevance. This form of executive education complements traditional executive education formats. Action learning is a highly generalizable activity for business schools and for business school faculty. Firms want more customization, and our field has generated enormous knowledge that deserves the opportunity to shape practice. Action learning promises high leverage for both faculty and firms. With this leverage also comes the opportunity for increased faculty insight and provocative research. Although there are real boundary issues to be resolved, my experience suggests that executive education in general and action-learning workshops in particular have the potential to move business schools more firmly into Pasteur’s Quadrant of knowing and doing; toward building powerful theories and fundamental ideas that impact practice.

REFERENCES

Adler, P., Benner, M., Brunner, D., MacDuffie, J., Staats, B., Takeuchi, H., Tushman, M., & Winter, S. (2009). Perspectives on the productivity dilemma. Journal of Operations Management, 27, 99–113.

Anderson, L. (2003, September 8). Companies still value training: Development: Survey shows that investing in executives has a big future. Financial Times, p. 5.

Argyris, C., & Schon, D. A. (1996). Organizational learning II: Theory, method and practice. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Bartunek, J. (2002). Corporate scandals: How should the Academy of Management members respond? Academy of Management Executive, 16, 138.

Bazerman, M. (2005). Conducting influential research: The need for prescriptive implications. Academy of Management Review, 30, 25–31.

Beer, M. (2001). Why management research findings are unimplementable: An action science perspective. Reflections, 2, 58–65.

Benner, M. J., & Tushman, M. (2002). Process management and technological innovation: A longitudinal study of the photography and paint industries. Administrative Science Quarterly, 47(4), 676–706.

Benner, M. J., & Tushman, M. (2003). Exploitation, exploration, and process management: The productivity dilemma revisited. Academy of Management Review, 28(2), 238–256.

Bennis, W., & O’Toole, J. (2005, May). How business schools lost their way. Harvard Business Review, 96–104.

Bok, D. (2003). Universities in the marketplace: The commercialization of higher education. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Brief, A. (2000). Still servants of power. Journal of Management Inquiry, 9(4), 342–351.

Conger, J., & Xin, K. (2000). Executive education in the 21st century. Journal of Management Education, 24(1), 73–101.

Ghoshal, S. (2005). Bad management theories are destroying good management practices. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 4, 75–91.

Harreld, B., O’Reilly, C., & Tushman, M. (2007). Dynamic capabilities at IBM: Driving strategy into action. California Management Review, 49(4), 1–22.

Hinings, C. R., & Greenwood, R. (2002). Disconnects and consequences in organization theory. Administrative Science Quarterly, 47, 411–421.

Huff, A. (2000). Citigroup’s John Reed and Stanford’s Jim March on management research and practice. Academy of Management Review, 14, 52–64.

Kaplan, R. (1998). Innovation action research: Creating new management theory and practice. Journal of Management Accounting Research, 10, 89–118.

Katz, R., & Tushman, M. (1979). Communication patterns, project performance, and task characteristics: An empirical evaluation and integration in an R&D setting. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 23, 139–162.

Khurana, R., Nohria, N., & Prenrice, D. (2005). Management as a profession. In J. Lorsch, A. Zelleke, & L. Berlowitz (Eds.), Restoring trust in American business. Cambridge, MA: American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

Kleinbaum, A., & Tushman, M. (2007). Building bridges: The social structure of interdependent innovation. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 1(1), 103–122.

Kuhn, J., & Marsick, V. (2005). Action learning for strategic innovation in mature organizations. Action Learning: Research and Practice, 2(1), 29–50.

Lawrence, P. R. (1992). The challenge of problem-oriented research. Journal of Management Inquiry, 1, 139–142.

Mintzberg, H. (2004). Managers not MBAs: A hard look at the soft practice of managing and management development. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler.

Nadler, D., & Tushman, M. (1998). Competing by design: The power of organizational architectures. New York: Oxford University Press.

O’Reilly, C., Harreld, B., & Tushman, M. (2009). Organizational ambidexterity: IBM and emerging business opportunities. California Management Review, 51(4), 75–99.

Pfeffer, J., & Fong, C. (2002). The end of business schools? Less success than meets the eye. Academy of Management Learning and Education, 1, 78–95.

Polzer, J., Gulati, R., Khurana, R., & Tushman, M. (2009). Crossing boundaries to increase relevance in organizational research. Journal of Management Inquiry, 18(4), 280–286.

Rynes, S. L., Bartunek, J. M., & Daft, R. L. (2001). Across the great divide: Knowledge creation and transfer between practitioners and academics. Academy of Management Journal, 44, 340–355.

Smith, W. K., & Tushman, M. L. (2005). Managing strategic contradictions: A top management model for managing innovation streams. Organization Science, 16(5), 522–536.

Stokes, D. E. (1997). Pasteur’s Quadrant: Basic science and technological innovation. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press.

Tichy, N., & Sherman, S. (1993). Control your destiny or someone else will. New York: Currency Doubleday.

Tushman, M. (1977). Special boundary roles in the innovation process. Administrative Science Quarterly, 22, 587–605.

Tushman, M. (1978). Task characteristics and technical communication in R&D. Academy of Management Journal, 21, 624–645.

Tushman, M. (2004). From engineering management/R&D management to the management of innovation, to exploiting and exploring over value nets: 50 years of research initiated by IEEE-TEM. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, 51(4), 409–411.

Tushman, M., & O’Reilly, C. (1997). Winning through innovation: A practical guide to leading organizational change and renewal. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Tushman, M., & O’Reilly, C. (2007). Research and relevance: Implications of Pasteur’s Quadrant for doctoral programs and faculty development. Academy of Management Journal, 50(4), 769–774.

Tushman, M., O’Reilly, C., Fenollosa, A., & Kleinbaum, A. (2007). Towards rigor and relevance: Executive education as a lever for enhancing academic relevance. Academy of Management Learning and Education, 6(3), 345–362.

Tushman, M. L., Smith, W., Wood, R., Westerman, G., & O’Reilly, C. (2010). Organizational designs and innovation streams. Industrial and Corporate Change. 19(5), 1331–1366.

Ulrich, D., Kerr, S., & Asheknas, R. (2002). The GE work-out: How to implement GE’s revolutionary method for busting bureaucracy and attacking organizational problems—fast. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Van de Ven, A. (2007). Engaged scholarship: Creating knowledge for science and practice. New York: Oxford University Press.

Van de Ven, A., & Johnson, P. (2004). Knowledge for science and practice. Minneapolis: Carlson School of Management, University of Minnesota.

Walsh, J., Tushman, M., Kimberly, J., Starbuck, W., & Ashford, S. (2007). On the relationship between research and practice: Debate and reflections. Journal of Management Inquiry, 16(2), 128–154.

Weick, K. (2004, August). On rigor and relevance of OMT. Paper presented at the Academy of Management Symposium, San Francisco.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Michael L. Tushman is the Paul R. Lawrence, Class of 1942 Professor at the Harvard Business School. At HBS, Tushman is the co-chair of the DBA program in management and is the faculty chair of the Advanced Management Program. Tushman also co-chairs the Leading Change and Organizational Renewal executive eduction program. His research focuses on the impact of technological change on organizational evolution, innovation streams and ambidextrous designs, and the characteristics of senior teams that can deal with paradoxical strategic requirements.