THIRTEEN

Professional Associations

Supporting Useful Research

PROFESSIONAL ASSOCIATIONS HAVE a visible, leading role to play in supporting and assimilating management-related research that has a useful impact on practice. Over the years, many reasons have been suggested for the great chasm that seems to exist between academic research and the practice of management. For purposes of this article, I adopt Gelade’s (2006) definition of practitioners, namely, those who make recommendations about the management or development of people in organizational settings or advise those who do. Research is relevant to the extent that it generates insights that practitioners find useful for understanding their own organizations and situations better than before (Vermeulen, 2007).

In Chapter 1, Research for Theory and Practice, Mohrman and Lawler describe three broad perspectives on the science-practice gap:

1. From an academia-centric perspective, the gap is the result of a knowledge-transfer problem. It assumes that knowledge emanates primarily from academia and focuses on ways to make practitioners knowledgeable about the “facts” that are discovered through academic research.

2. A second perspective argues that knowledge of theory and knowledge of practice are distinct—substantively, ontologically, and epistemologically. The challenge, then, is to explore and benefit from the complementary features of these distinct forms of knowledge.

3. The third perspective views the source of the academic-practice gap as a knowledge-production problem. To bridge the gap, it argues for research approaches that engage both academics and practitioners in a collaborative-learning community. To do that, it is necessary to combine the knowledge of practitioners and the knowledge of academics from different disciplines through all stages of the research process.

Despite calls by researchers for more enlightened thinking and strategies to bridge the gap (Bartunek, 2007; Cascio, 2007, 2008; Cascio & Aguinis, 2008a; Latham, 2009; Rynes, 2007; Rynes, Bartunek, & Daft, 2001; Rynes, Colbert, & Brown, 2002; Rynes, Giluk, & Brown, 2007; Saari, 2007; Starbuck (in Barnett, 2007), it remains stubbornly resistant.

To date, professional associations have actively supported management-related research that has a useful impact on practice, albeit in different ways and with differing degrees of success. This chapter will examine what five different professional associations have done and are doing to bridge the gap. Those associations are the Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology (SIOP); the Society for Human Resource Management (SHRM) Foundation, the Human Resource Planning Society (HRPS); the Academy of Management (AOM); and the Labor and Employment Relations Association (LERA), formerly the Industrial Relations Research Association.

Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology

According to its website, the SIOP’s mission is to enhance human well-being and performance in organizational and work settings by promoting the science, practice, and teaching of industrial-organizational (I/O) psychology. Among other activities, SIOP engages in the following:

![]() Supports SIOP members in their efforts to study, apply, and teach the principles, findings, and methods of industrial-organizational psychology

Supports SIOP members in their efforts to study, apply, and teach the principles, findings, and methods of industrial-organizational psychology

![]() Provides forums for industrial-organizational psychologists to exchange research, insights, and information related to the science, practice, and teaching of industrial-organizational psychology

Provides forums for industrial-organizational psychologists to exchange research, insights, and information related to the science, practice, and teaching of industrial-organizational psychology

For decades, SIOP has actively endorsed the scientist-practitioner model (Bass, 1974; Dunnette, 1990; Murphy & Saal, 1990; Rupp & Beal, 2007). That model discourages both practice that has no scientific basis and research that has no clear implications for practice (Murphy & Saal, 1990). Toward that end, SIOP offers preconference workshops in which academics and practitioners can work together on important problems. Sessions at the annual conference provide forums for the exchange of information related to science and practice, but SIOP has moved well beyond the conference itself to promote collaboration and a deeper understanding of issues that are important to scientists and to practitioners. It also offers a blog, the SIOP Exchange.

The Exchange makes use of an interactive blog format in which professionals in the academic and applied domains submit posts that detail the latest happenings on popular topics that generate conversation, such as hot-topic issues, findings not yet published, and applications of I/O psychology that are new and innovative. Professionals from across the world can then ask questions, provide comments, and respond to other comments in reaction to these posts. New material is posted regularly, and every post is tagged with keywords so that topics of interest are easy to find.

Beginning in 2005, SIOP began an annual two-day event known as the Leading-Edge Consortium in an effort to integrate the science and the application of I/O psychology to important organizational issues. Each consortium addresses an important issue that is relevant to science and to practice. I/O psychologists working in organizations both large and small, together with leading academics, listen to presentations, interact in small-group sessions, and have extensive opportunities to network over the two days. For example, the key themes from 2005 to 2009 were the following:

![]() 2005 – Leadership at the Top: The Selection of Executive Talent

2005 – Leadership at the Top: The Selection of Executive Talent

![]() 2006 – Talent Attraction and Development

2006 – Talent Attraction and Development

![]() 2007 – Enabling Innovation in Organizations

2007 – Enabling Innovation in Organizations

![]() 2008 – Executive Coaching for Effective Performance

2008 – Executive Coaching for Effective Performance

![]() 2009 – Selection and Assessment in a Global Setting

2009 – Selection and Assessment in a Global Setting

In summary, SIOP has extended a welcoming hand to practitioners, and they have responded by actively participating in preconference workshops, in annual conference presentations, in the SIOP Exchange blog, and in Leading-Edge consortia. This active involvement of scientists and practitioners has deepened the understanding that each has of the other’s “thought world” (perspectives 2 and 3 identified by Mohrman and Lawler in Chapter 1, Research for Theory and Practice), and I believe that it has enriched both science and practice.

Society for Human Resource Management Foundation

The Society for Human Resource Management is the world’s largest association devoted to human resource management. Representing more than 250,000 members in 140 countries, SHRM has more than 575 affiliated chapters within the United States and subsidiary offices in China and India.

The SHRM Foundation is the 501(c)(3) nonprofit affiliate of SHRM. Steered by a 14-member board of directors composed of equal numbers of academics and practitioners, the foundation is a leading funder of human resources (HR) research grants up to $200,000 each. There is no requirement that researchers be U.S. based, and in recent years, the funding rate has been similar for researchers both inside and outside the United States. Proposals are reviewed three times each year, and whether funded or not, submitters receive detailed, constructive feedback about their proposals.

In the past 12 years, the foundation has funded more than $2.3 million in research grants for 107 research projects. Fully 88 percent of completed projects have had significant impact, including articles published in academic journals and presentations at national conferences. The journals publishing the most foundation research are Human Resource Management, the Journal of Applied Psychology, and Personnel Psychology.

The foundation funds original, empirical academic research that advances the HR profession. The research is targeted at an academic audience, while also having direct, actionable implications for HR practice, whether the focus is on addressing current challenges or on understanding emerging trends. The foundation will consider any topic and any methodology as long as the proposed methodology is sound and appropriate for the proposed research question(s). Those research questions typically (but not solely) take the form of theoretically derived hypotheses.

In addition, the research must have clear applicability for HR practice and help contribute to evidence-based HR. At least one academic and one practitioner review each proposal. Projects that ultimately are funded share two common characteristics: (1) they are suitable for leading academic journals; and (2) they are likely to yield practical implications for HR managers (i.e., applied outlets should be interested in the research results). The emphasis clearly is on fostering applied research with practical implications for management practice.

In considering each proposal, the committee uses the following eight criteria:

1. Overall strengths of the proposal

2. Overall weaknesses of the proposal

3. The quality of the conceptual framework

4. The quality of the methodology

5. The likelihood of the study being published in a top-tier academic HR journal

6. The likelihood of the study yielding relevant, actionable insights for practitioners

7. The likelihood of the study being completed as outlined (and within two years)

8. The appropriateness of the requested budget

In addition to funding research, the foundation also hosts academic-practitioner forums through its annual Thought Leaders Retreat, and it produces publications and educational resources to advance the HR profession. It also awards $100,000 in student scholarships each year, and makes four $5,000 dissertation awards through the HR Division of the Academy of Management.

Thought Leaders Retreat

Created by the SHRM foundation in 1999, the annual Thought Leaders Retreat brings together a select group of approximately 120 leading-edge thinkers and executives in the broad field of HR. Over one-and-a-half days, participants explore issues shaping the future of the profession and their implications for research and practice. Themes from the past six retreats were the following:

![]() 2009 – Positioning Your Organization for Recovery

2009 – Positioning Your Organization for Recovery

![]() 2008 – Workforce 2012: Attracting and Retaining Top Talent

2008 – Workforce 2012: Attracting and Retaining Top Talent

![]() 2007 – Leadership Succession in a Changing World

2007 – Leadership Succession in a Changing World

![]() 2006 – Employee Engagement: Lessons and Questions

2006 – Employee Engagement: Lessons and Questions

![]() 2005 – HR Leadership for the Next Decade

2005 – HR Leadership for the Next Decade

![]() 2004 – HR Leadership at the Board Level

2004 – HR Leadership at the Board Level

Effective Practice Guidelines

This series of monographs presents important research findings in a condensed, easy-to-use format for busy HR professionals. The overall objective is to answer two questions: (1) What do we know? and (2) What are the implications for practice? This series addresses perspective number 1 of the scientist-practitioner gap noted at the beginning of the chapter. That is, it focuses on ways to make practitioners knowledgeable about the “facts” that are discovered through academic research.

An expert who is thoroughly knowledgeable about the relevant research writes each report. Prior to publication, a committee of academics and practitioners reviews the report, usually providing multiple rounds of review and feedback. Then the report is professionally edited and laid out for easy reading. The following are the reports produced to date:

![]() Employment Downsizing and Its Alternatives

Employment Downsizing and Its Alternatives

![]() Learning System Design

Learning System Design

![]() Human Resource Strategy

Human Resource Strategy

![]() Developing Leadership Talent

Developing Leadership Talent

![]() Implementing Total Rewards Strategies

Implementing Total Rewards Strategies

![]() Employee Engagement and Commitment

Employee Engagement and Commitment

![]() Selection Assessment Methods

Selection Assessment Methods

![]() Performance Management

Performance Management

DVD Series

Based on interviews with top executives at leading companies, these educational digital video discs (DVDs), each approximately 20 minutes in length, present case studies of strategic human resources management (HRM) in actual organizations. They also include research-based lessons for practice that other organizations can use. Each comes with a detailed discussion guide and a PowerPoint® presentation to create high-impact presentations for professional development or classroom use. The SHRM Foundation’s DVDs are used in more than 400 universities in 43 countries. The following titles are available:

![]() Once the Deal Is Done: Making Mergers Work (Featuring Bupa Australia)

Once the Deal Is Done: Making Mergers Work (Featuring Bupa Australia)

![]() World Economic Forum: Creating Global Leaders

World Economic Forum: Creating Global Leaders

![]() Seeing Forward: Succession Planning at 3M

Seeing Forward: Succession Planning at 3M

![]() Trust Travels: The Starbucks Story

Trust Travels: The Starbucks Story

![]() Ethics: The Fabric of Business (Lockheed Martin)

Ethics: The Fabric of Business (Lockheed Martin)

![]() Fueling the Talent Engine: Finding and Keeping High Performers (Yahoo!)

Fueling the Talent Engine: Finding and Keeping High Performers (Yahoo!)

![]() HR in Alignment: The Link to Business Results (SYSCO)

HR in Alignment: The Link to Business Results (SYSCO)

![]() HR Role Models (Cisco, Blue Cross, Qualcomm)

HR Role Models (Cisco, Blue Cross, Qualcomm)

Finally, the foundation has sponsored two books (Evaluating Human Resources Programs: A 6-Phase Approach for Optimizing Performance and Making Mergers Work) and three short reports (Use and Management of Downsizing as a Corporate Strategy; Strategic Research: Human Capital Challenges; and Connecting Research to HR Practice).

In summary, by funding grants and providing scholarships to worthy proposals that have direct implications for management practice, the SHRM Foundation is working to close the science-practice gap. Its Thought Leaders Retreat, Effective Practice Guidelines, DVD series, reports, and books contribute further to this objective. Through multiple channels, the foundation is addressing all three of the perspectives on the science-practice gap noted at the beginning of the chapter.

Human Resource Planning Society

HRPS focuses on one broad area: strategic human resource management. On its website, HRPS describes itself as “The global association of senior HR professionals in the world’s leading organizations.” Its mission, vision, and strategy are similarly clear. Its mission is “to help organizations enhance their performance through the strategic management of human resources.” Its vision is “to be the preferred provider of leading-edge HR knowledge in key strategic areas.” Finally, its strategy is “to bring together a diverse group of thought leaders and practitioners in order to align resources to extend knowledge in selected areas.”

There are many knowledge areas for which HR professionals are held accountable, but HRPS addresses what it feels are the most critical and strategic ones. Through its research, HRPS has identified five key knowledge areas that are the focus of the HRPS strategy implementation. The five areas are: HR strategy and planning, leadership development, talent management, organizational effectiveness, and building a strategic HR function.

These five areas drive the content and outcomes of all HRPS activities, from workshops and teleconferences to articles in the society’s journal, People & Strategy, publications, and research. People & Strategy is a quarterly journal that contains current theory, research, and practice in strategic human resource management. It focuses on human resource practices that contribute to the achievement of organizational effectiveness. People & Strategy includes original articles as well as sections on current practices, research, and book reviews.

A 20-person board of directors, consisting of 18 senior HR executives and independent consultants and two academics, governs HRPS. Its purpose is to oversee the alignment of HRPS activities with the stated vision, mission, and strategy. The executive committee of the board—composed of HRPS officers, board members, and the president and CEO—is responsible for providing and guiding the strategic direction of the society.

HRPS provides a variety of educational forums and activities for its members. It hosts an annual global conference as well as a fall executive forum, attended by global chief human resource officers, vice-presidents, and directors, HR thought leaders, faculty, consultants, and senior line managers. It also provides regular webcasts. The webcasts cover HR hot topics, best practices, and analysis presented live by eminent HR thought leaders. Each is moderated to allow for a question-and-answer period.

With respect to market segmentation of the professional associations discussed thus far, SIOP tends to focus on PhD-level members, academics as well as practitioners; SHRM primarily attracts mid-level HR professionals and some senior-level HR officers; and HRPS is targeted squarely on senior-level HR officers and managers. All three provide rich opportunities for academics to interact with practitioners, and all three clearly support useful, relevant research. They provide opportunities to learn and observe firsthand the “mental models” that practitioners tend to rely on and also the theoretical frameworks that guide academic research. The operative word in the foregoing sentence is “opportunities.” Systematic research that demonstrates the actual outcomes of those opportunities is sorely lacking, although anecdotal evidence suggests that there is some degree of cross-pollination.

Academy of Management

According to its website, the Academy of Management is a leading professional association for scholars dedicated to creating and disseminating knowledge about management and organizations. Founded in 1936, the AOM is the oldest and largest scholarly management association in the world. Today, the academy is the professional home of 18,889 members from 108 nations. It comprises 23 divisions and one interest group. Academy members are scholars at colleges, universities, and research institutions, as well as practitioners with scholarly interests from business, government, and not-for-profit organizations. Although most of its members are academics, as a professional association, the AOM seeks and encourages members from all walks of life who are interested in advancing the scholarship of management knowledge.

The academy’s central mission is to enhance the profession of management by advancing the scholarship of management and enriching the professional development of its members. The academy is committed to shaping the future of management research and education. According to its Statement of Strategic Direction, adopted by the board of governors in April 2001, the mission and objectives of the AOM suggest several important activities, one of which is a major annual conference that consists of a variety of important activities, ranging from workshops to paper presentations and job-placement interviews. In 2009, more than 10,000 people attended the AOM annual conference. It provides an opportunity for members from around the world to come together to build and renew professional and social relationships.

The AOM continually seeks innovative ways to make its annual meeting a better venue for sharing and learning, for example:

![]() From high-quality research. For example, by circulating papers on the Web beforehand, creating more symposia, providing more opportunities for debate of both theoretical and applied issues, and holding theme meetings across divisions.

From high-quality research. For example, by circulating papers on the Web beforehand, creating more symposia, providing more opportunities for debate of both theoretical and applied issues, and holding theme meetings across divisions.

![]() By making the annual meeting more engaging. For example, by designing a conference within a conference, providing more virtual spaces for members to interact, arranging special sessions for doctoral students to share papers, holding orientation and “get-acquainted” meetings for new members and attendees from around the world, providing additional incentives to divisions and interest groups for innovation, and by sharing best practices across divisions.

By making the annual meeting more engaging. For example, by designing a conference within a conference, providing more virtual spaces for members to interact, arranging special sessions for doctoral students to share papers, holding orientation and “get-acquainted” meetings for new members and attendees from around the world, providing additional incentives to divisions and interest groups for innovation, and by sharing best practices across divisions.

![]() By making the annual meeting more developmental for members. For example, by holding professional-development workshop (PDW) sessions for mid-career professionals on updating methodologies and finding new research interests, by organizing more symposia and paper sessions on teaching and practice, and by creating forums for “work in progress.”

By making the annual meeting more developmental for members. For example, by holding professional-development workshop (PDW) sessions for mid-career professionals on updating methodologies and finding new research interests, by organizing more symposia and paper sessions on teaching and practice, and by creating forums for “work in progress.”

![]() By enabling research presented at the annual meeting to make a greater impact on organizations and the larger society. For example, by seeking feedback from practitioners about issues in need of research, including more practitioners in division programs, and providing summaries of practice implications from journals on the AOM website.

By enabling research presented at the annual meeting to make a greater impact on organizations and the larger society. For example, by seeking feedback from practitioners about issues in need of research, including more practitioners in division programs, and providing summaries of practice implications from journals on the AOM website.

The AOM is committed to advancing theory, research, education, and practice in the field of management. It publishes four journals, each of which broadly contributes to this objective while emphasizing a particular scholarly aspect of it. The Academy of Management Review (AMR) provides a forum to explicate theoretical insights and developments. Articles published in the Academy of Management Journal (AMJ) empirically examine theory-based knowledge. The Academy of Management Learning and Education (AMLE) provides a forum to examine learning processes and management education. Articles published in the Academy of Management Perspectives (AMP)—formerly the Academy of Management Executive (AME)—use research-based knowledge to inform and improve management practice. In addition, a quarterly newsletter contains news, events, and activities of the academy. Divisions and interest groups also produce newsletters.

The Academy of Management’s newest publication is an annual series, the Academy of Management Annals, written to provide up-to-date, comprehensive examinations of the latest advances in various management fields. Each volume features critical research reviews written by leading management scholars. These reviews explore a wide variety of research topics per volume, summarize established assumptions and concepts, identify problems and factual errors, and illuminate possible avenues for further study. The Annals are geared toward academic scholars in management and professionals in allied fields, such as sociology of organizations and organizational psychology.

A final initiative is AOM Online. It includes current information about the academy’s activities, helpful links, resources for professional development, and online discussion groups. Its goal is to be an electronic information supersource, offering management scholars a gateway to resources they can use to create, disseminate, and apply knowledge about management and organizations. Making effective use of the Web, the AOM hosts 50 electronic mailing lists, connecting nearly 10,000 people. Members host these lists at their institutions, thereby linking thousands more. At a broader level, AOM Online fulfills the following six functions. It is

![]() an interactive knowledge repository for research, teaching, practice, and professional activities

an interactive knowledge repository for research, teaching, practice, and professional activities

![]() a learning portal with examples, tools, discussions, and electronic communities to ignite ideas and foster experimentation

a learning portal with examples, tools, discussions, and electronic communities to ignite ideas and foster experimentation

![]() a distribution channel, broadcasting, abstracting, and generating new information

a distribution channel, broadcasting, abstracting, and generating new information

![]() a community builder, linking members to each other and to management scholars and professionals around the world

a community builder, linking members to each other and to management scholars and professionals around the world

![]() a practice and policy resource, drawing academia, educational agencies, and the private sector more closely together

a practice and policy resource, drawing academia, educational agencies, and the private sector more closely together

![]() a Web-development model with distributed responsibility for content development by committees, divisions, and volunteers

a Web-development model with distributed responsibility for content development by committees, divisions, and volunteers

Labor and Employment Relations Association

LERA, founded in 1947 as the Industrial Relations Research Association (IRRA), is an organization for professionals in industrial relations and human resources. The national organization has more than 3,000 members and includes more than 50 local chapters where members meet colleagues in the private, public, and federal sectors, as well as faculty from local universities and third-party neutrals. It provides opportunities for professionals interested in all aspects of labor and employment relations to network, to share ideas, and to learn about new developments, issues, and practices in the field. LERA provides a unique forum where the views of representatives of labor, management, government, and academics, as well as advocates and neutrals, are welcome. LERA also sponsors interest sections in collective bargaining; dispute resolution; international and comparative employment relations; labor and employment law; labor markets and economics; labor studies and union research; and globalization, investment, and trade.

LERA holds an annual membership and professional-development meeting, as well as a national policy forum. It also grants two John T. Dunlop Scholar Awards each year. One goes to an academic who makes the best contribution to international or comparative labor and employment research. A second recognizes an academic for research that addresses an industrial relations or employment problem of national significance in the United States.

The association also publishes a number of research reports and books, as well as an annual compendium of research, annual proceedings, and a newsletter. Its biannual journal, Perspectives on Work, covers a variety of labor-relations topics, including law, workplace culture, labor history, the effect of economic dislocation and change on employer-employee relations, corporate governance, workplace sociology and leadership, and other issues. Expert workers, students, labor leaders, human resources managers, arbitrators, mediators, government officials, and academics write articles. The target audience consists of academics and practitioners in labor and employment relations, from both a managerial and a worker perspective.

Because the competitive and employment dynamics of different industries warrant industry-specific analysis and action, LERA established a network of tripartite (management, labor, and government) industry councils. Councils are currently organizing in aerospace, airline, automotive, construction, health care, higher education, public sector, materials, utilities, and other industries. Enabled with a major grant from the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, this initiative represents a key structural addition to the association.

Perhaps because of the highly applied nature of the problems studied, LERA, more than any other association we have examined, affords opportunities for academics and practitioners to collaborate in a manner that enriches and deepens understanding of each other’s perspectives. Both groups can contribute reciprocally to progress in addressing the kinds of problems that each faces. This problem-focused research is the sort that Mohrman and Lawler (Chapter 1, Research for Theory and Practice) referred to as “no longer defined through the narrow boundaries of disciplines and professions.” Why don’t more academics and practitioners engage in problem-focused research? What are the obstacles, and how can they be overcome?

Creating a Future of Relevant, Useful Research

In the conclusion to their chapter, Mohrman and Lawler (Chapter 1, Research for Theory and Practice) posed two fundamental questions: “How do researchers who have been trained by faculty who are unconcerned with bridging the gap and who are in institutions that do not reward or value it, learn to carry out more connected research? How will they come to feel that this is a legitimate route to take?” In fact, many academics place little value on doing relevant research. Palmer (2006) argued that a silent majority of them advocate disinterest in practice in order to achieve scientific objectivity. Doing so ensures that their interests and values will not be subverted to those of management and that they will not become mere servants of those in positions of power (Baritz, 1960). To the extent that this is true, however, then one can argue, as do Tushman and O’Reilly (2007), that this self-imposed distance from practical concerns reduces the quality of our field’s research, undermines the external validity of our theories, and reduces the overall relevance of the data used to test ideas.

Beyond that, many academics do not need to do relevant research, because they are not rewarded for doing it. Thus an online survey of members of the Academy of Management (Shapiro, Kirkman, & Courtney, 2007) concluded that universities’ promotion and tenure systems provide disincentives for conducting and publishing practitioner-oriented research. Although professional associations may do an excellent job of providing forums that bring academics and practitioners together, and in fact they do, unless academics place a strong value on doing relevant, useful research, they will not avail themselves of the opportunities to connect with practitioners. Ultimately, therefore, it’s a question of values. Commenting on the current state of management research, Starbuck (in Barnett, 2007) noted:

People should do management research because they want to contribute to human welfare. Those who are professors of management are people of superior abilities and they should use these abilities for purposes greater than themselves . . . I also observe that many doctoral students and junior faculty are focusing on achieving social status and job security and are viewing research methods as tools to construct career success. Few of them seem apt to initiate or even to participate in significant reorientations. (Barnett, 2007, pp. 126–127)

Academics and practitioners live in different “thought worlds,” distinct knowledge and practice communities. Academics typically strive to develop and refine theoretically framed, generalizable knowledge (often devoid of context). Practitioners develop and refine knowledge that enables them to solve operational problems that are immersed in context. Both parties have to work hard to appreciate the “mental models” that their counterparts live by, and some just do not want to do so.

With respect to one subset of academics, Johns (2006) noted: “Some quantitative researchers seem almost desperate to ensure that reviewers and readers see their results as generalizable. To facilitate this, they describe research sites as blandly as possible—dislocated from time, place, and space—and omit details of how access was negotiated” (p. 404). In contrast, Cascio and Aguinis (2008b) argued that, at least in the context of forecasting job performance, genuine progress is more likely if researchers focus on in situ performance, that is, specification of the broad range of effects—situational, contextual, strategic, and environmental—that may affect individual, team, or organizational performance. To be able to do that, academics must connect with practitioners and get into organizations in order to understand deeply the many variables that affect performance. Academics must see that as part of their role; they have to want to do it. Given the stated missions and activities of the professional associations that we have examined, it is clear that those associations want to provide visibility and recognition to relevant, useful research and to those who conduct it.

Practitioners want actionable knowledge. One of the reasons they find techniques such as the situational interview (Latham et al., 1980) and goal setting (Latham & Saari, 1982) to be actionable is precisely because they were developed and shown to work in real organizational contexts with real people. Professional associations such as SIOP, the SHRM Foundation, HRPS, AOM, and LERA are actively trying to promote actionable knowledge and to create practice-accessible knowledge through the dissemination of research reports (in understandable language and with appropriate qualifiers), together with tools and solutions, such as science-practice networking websites. Yet they can do more.

They can offer interactive sessions in which academics and practitioners can work together on important problems (Cascio & Aguinis, 2008a; Bartunek, 2007). SIOP’s pre-conference workshops partially address this issue, but professional associations can and should offer more focused sessions that are truly interactive. Rynes (2007) noted that this is probably the single most important thing that our professional associations can do to narrow the academic-practitioner gap. Ultimately, however, as Tushman (Chapter 9, On Knowing and Doing) has noted, boundaries are extremely important, because if managers, and especially management teams, trust you, you can collect data. Professional associations can bring academics and practitioners together, but there are limits to what they can do. For example, they cannot ensure mutual trust, because trust only develops over time through personal interactions. Yet, if academics and practitioners do not have the opportunity to meet and to share ideas and insights, then there is almost no opportunity for further collaboration.

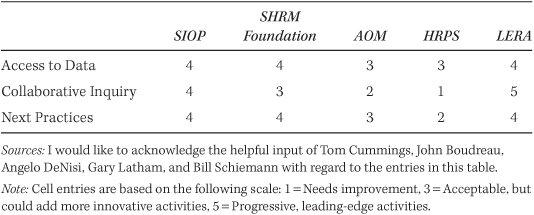

As a general strategy to foster relevant, useful research, professional associations should strive to achieve three broad, interrelated objectives: promote collaborative inquiry, provide opportunities for access to data, and focus less on “best” practices than on “next” practices. With respect to access to data, for example, SIOP does not actually offer data sets to researchers, but it does bring practitioners and researchers together through its many programs, and in that sense it creates opportunities for researchers to get access to data. Table 13.1 provides a rough “scorecard” that assesses how each of the professional associations that we have examined is doing with respect to these three objectives.

TABLE 13.1 Assessment of Five Professional Associations on Three Broad Objectives

As the cell entries in Table 13.1 make clear, professional associations are striving to achieve these three objectives, but there is certainly room for improvement. Whereas the AOM is oriented primarily toward academics, SHRM is heavily oriented toward mid-level practitioners—even though the SHRM Foundation has been reaching out to academics for many years. SIOP does include practitioners but primarily serves those with advanced degrees. LERA is small and focuses on employee-relations issues, and by its very nature, it promotes collaboration between academics and practitioners in the production of relevant, useful research.

Conclusion

The focus of this chapter has been on academics and what professional associations can do to help them create actionable research. Although not treated in this chapter, the other side is no less important. Why should practitioners pay attention to research findings? To be sure, consulting firms, executive-education firms, and professional societies do research. Although it may not be the kind of rigorous, peer-reviewed research that academics publish, practitioners often regard it as useful for their purposes. Most of them are unlikely to read professional journals, and managers require no certification to practice, but at least one large group of managers, HR managers, often does seek certification. The Society for Human Resource Management could incorporate more research-based content into its certification study guides and examinations, which thousands of practitioners take every year (Cascio, 2007).

At a more general level, Ian Ziskin, former chief HR officer at Northrop Grumman, noted that theory is problem solving without a customer, while practice is problem solving without a theory (Ziskin, 2009). Organizations may not be interested in supporting research and sharing data with academic researchers, but they always have problems. If academics think of research as problem solving, and frame it that way for practitioners, they may find that practitioners are more receptive to their messages.

Indeed, from an operational perspective, practitioners need solutions to the pressing problems that they face, and they will actively seek new knowledge generated through rigorous research that will help them find those solutions. At the same time, as Ziskin (2009) noted, it is not enough to show that a problem exists; academics (and practitioners) have to create “love” for that problem within the organization. To do that, think carefully about how to frame the problem, and how to address it. Make sure you can answer some fundamental questions such as these: What is the problem? Who cares? Is there a customer for that problem? What is the attention span that people have to address it? Will anybody pay for it? When we are all done, can we brief management about what we found? Practitioners see problems in broad themes and broad patterns (e.g., talent management, retention). Many experts (and non-experts) come to organizations with proposed solutions that sound the same. Like a winning strategy, you must be able to differentiate your approach from others if you want to gain access and have the opportunity to solve the problem in question.

Professional associations are actively reaching out to practitioners to solicit their participation and ideas. Some, like the SHRM Foundation, have institutionalized practitioner input and review on research projects. Bridging the academic-practitioner divide is a journey that has no finish line, but the kinds of innovations and activities that professional associations are undertaking provide cause for optimism that genuine progress can be made.

REFERENCES

Baritz, L. (1960). The servants of power. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press.

Barnett, M. L. (2007). (Un)learning and (mis)education through the eyes of Bill Starbuck: An interview with Pandora’s playmate. Academy of Management Learning and Education, 6, 114–127.

Bartunek, J. (2007). Academic–practitioner collaboration need not require joint or relevant research: Toward a relational scholarship of integration. Academy of Management Journal, 50, 1323–1333.

Bass, B. M. (1974). The substance and the shadow. American Psychologist, 29, 870–886.

Cascio, W. F. (2007). Evidence-based management and the marketplace for ideas. Academy of Management Journal, 50, 1009–1012.

Cascio, W. F. (2008). To prosper, organizational psychology should bridge application and scholarship. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 29, 455–468.

Cascio, W. F., & Aguinis, H. (2008a). Research in industrial and organizational psychology from 1963 to 2007: Changes, choices, and trends. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93, 1062–1081.

Cascio, W. F., & Aguinis, H. (2008b). Staffing twenty-first-century organizations. Academy of Management Annals, 2(1), 133–165.

Dunnette, M. D. (1990). Blending the science and practice of industrial and organizational psychology: Where are we and where are we going? In M. D. Dunnette & L. M. Hough (Eds.), Handbook of industrial and organizational psychology (2d ed., vol. 1, pp. 1–27). Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press.

Gelade, G. A. (2006). But what does it mean in practice? The Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology from a practitioner perspective. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 79, 153–160.

Johns, G. (2006). The essential impact of context on organizational behavior. Academy of Management Review, 31, 386–408.

Latham, G. P. (2009). Becoming the evidence-based manager: Making the science of management work for you. Boston: Davies Black.

Latham, G. P., & Saari, L. M. (1982). The importance of union acceptance for productivity improvement through goal setting. Personnel Psychology, 35, 781–787.

Latham, G. P., Saari, L. M., Pursell, E. D., & Campion, M. A. (1980). The situational interview. Journal of Applied Psychology, 65, 422–427.

Murphy, K. R., & Saal, F. E. (1990). What should we expect from scientist–practitioners? In K. R. Murphy & F. E. Saal (Eds.), Psychology in organizations: Integrating science and practice (pp. 49–66). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Palmer, D. (2006). Taking stock of the criteria we use to evaluate one another’s work: ASQ fifty years out. Administrative Science Quarterly, 51, 535–559.

Rupp, D. E., & Beal, D. (2007). Checking in with the scientist–practitioner model: How are we doing? Industrial–Organizational Psychologist, 45, 35–40.

Rynes, S. L. (2007). Let’s create a tipping point: What academics and practitioners can do, alone and together. Academy of Management Journal, 50, 1046–1054.

Rynes, S. L., Bartunek, J. M., & Daft, R. L. (2001). Across the great divide: Knowledge creation and transfer between practitioners and academics. Academy of Management Journal, 44, 340–355.

Rynes, S. L., Colbert, A. E., & Brown, K. G. (2002). HR professionals’ beliefs about effective human resource practices: Correspondence between research and practice. Human Resource Management, 41, 149–174.

Rynes, S. L., Giluk, T. L., & Brown, K. G. (2007). The very separate worlds of academic and practitioner periodicals in human resource management: Implications for evidence-based management. Academy of Management Journal, 50, 987–1008.

Saari, L. (2007). Commentary on the very separate worlds of academic and practitioner periodicals. Academy of Management Journal, 50, 1043–1045.

Shapiro, D. L., Kirkman, B. L., & Courtney, H. G. (2007). Perceived causes and solutions of the translation problem in management research. Academy of Management Journal, 50, 249–266.

Tushman, M., & O’Reilly, C., III. (2007). Research and relevance: Implications of Pasteur’s quadrant for doctoral programs and faculty development. Academy of Management Journal, 50, 769–774.

Vermeulen, F. (2007). “I shall not remain insignificant”: Adding a second loop to matter more. Academy of Management Journal, 50, 754–761.

Ziskin, I. (2009, December). The role of practitioners in the creation of knowledge. Panel discussion at the workshop, Doing Research That Is Useful for Theory and Practice—25 Years Later, University of Southern California, Los Angeles.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Wayne F. Cascio holds the Robert H. Reynolds Chair in Global Leadership at the University of Colorado Denver. He has served as President of the Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology (1992–1993), Chair of the SHRM Foundation (2007) and of the HR Division of the Academy of Management (1984), and as a member of the Academy of Management’s Board of Governors (2003–2006). He has authored or edited 24 books on human resource management, including Investing in People (2nd ed., with John Boudreau, 2011), Managing Human Resources (8th ed., 2010), and Applied Psychology in Human Resource Management (7th ed., with Herman Aguinis, 2011). He received an honorary doctorate from the University of Geneva (Switzerland) in 2004, and in 2008 he was named by the Journal of Management as one of the most influential scholars in management in the past 25 years.