The Theory of Transfer Pricing

Introduction

Around the world, the things we buy increasingly have a transnational source. People in Japan wear Levi’s, while Americans drive Toyotas and Cypriots eat Dutch fruit. Yet, despite the fact that we are consuming more international products than ever before, one of the ways in which nations remain distinct is in how high or low prices are in their local markets. That Chilean wine costs more in Nicosia than Santiago should come as no surprise. It has longer to travel and more associated costs in getting it to market. The same applies to other important consumer goods, such as petrol and flour, yet local products are not always the cheapest. We like to think that the closer a product is to its source, the less it will cost but that rationale does not apply all the time. Let’s look at Apple’s iPod Nano. It is made in China or Taiwan for US and British markets. The costs associated with bringing it to market in either country are relatively similar. So why does one cost so much more in Britain than the United States?1

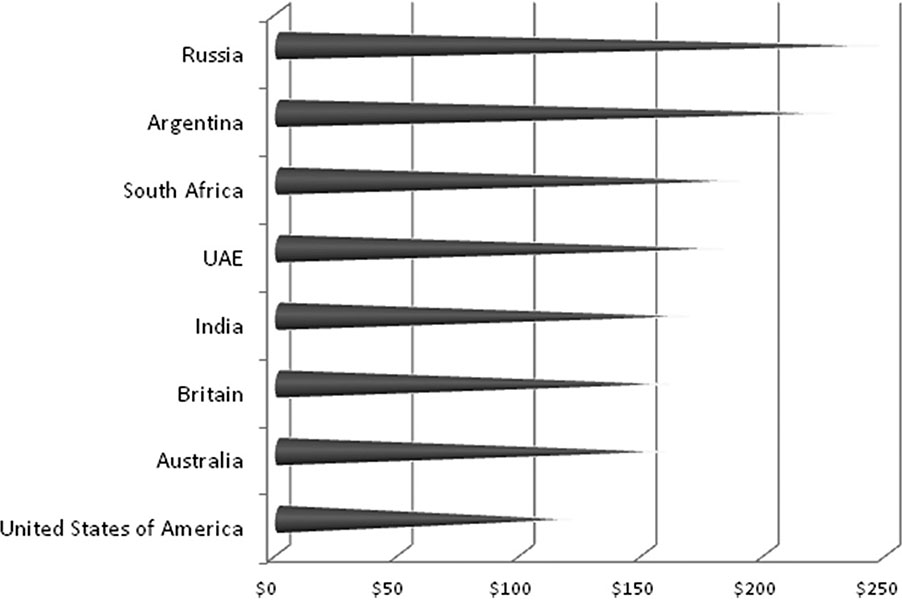

Much of the difference is related to tariffs and consumption taxes, or the lack thereof, which affect the price. But it is not just these. Another reason is currency valuation. Right now, the US dollar is weak compared with many other currencies; so, in theory, items bought there should cost more, yet, as we have seen with the i-Pod Nano example, that is not always so. In the case of most consumer goods, the price at which they are sold generally reflects the varying levels of consumer purchasing power in individual countries. If this were true, the i-Pod Nano, while more expensive in some countries, ought to have a comparable cost in terms of actual purchasing power. Logically then, we would expect prices to be lower across the board in poorer countries and more expensive in wealthier nations. However, this is not always the case as we can see from Figure 2.1 where the i-Pod Nano prices in some selected countries, both rich and poor, are shown.

Figure 2.1. Comparative prices for Apple’s iPod (in US$).

Another factor that needs to be considered is the MNEs’ pricing strategy. In this, organizations have a lot of discretion when it comes to setting prices. There is nothing to stop them setting dramatically different prices in different places in order to make the most profit. In other words, an organization will charge more for a product in one market than another because it knows consumers have no alternative. What is more, retailers selling the organization’s products can also charge more if they feel that consumers will bear the cost.

Such is the cutthroat world of commercial trade, where an organization’s ability to establish an acceptable pricing policy for its products, services, or both is a crucial element of business sustainability. Many worry that they are asking too much and yet underpricing hurts as much as overpricing does. If the price of your product or service is too high, potential customers will look for a more affordable alternative. On the other hand, if the price is too low, potential customers will think it cannot be that good. Here I am reminded of the story of Goldilocks and the Three Bears, where, on entering the house of the three bears in search of food, Goldilocks sees three bowls of porridge on the table. On trying the first bowl, she declares it too hot. The porridge in the second bowl is too cold for her but in the third bowl, it is “just right.” Pricing is exactly like that. It may be too high, it may be too low, or it may be just right. And, just as Goldilocks decided on the choice of porridge bowl, the buyer of an organization’s products, services, or both will decide on the rightness of the price.

It has always been this way. If an organization operates under conditions of perfect competition, it has no choice but to accept the price a buyer is prepared to offer. At the other extreme, if an organization is a monopolist, then it can set any price it chooses. The reality is usually somewhere in between and, as such, the asking price needs to be very carefully considered relative to those of close competitors. Of course, that is not all an organization has to think about. The asking price must also take into consideration the total cost of providing that product or service—something that is rarely known but is often guessed.

They are just two of the aspects of pricing. A third relates to the investment necessary to deliver your products or services to the customer and the return required on that investment. This is only one more complexity in an already intricate environment. Nonetheless, to price your products, services, or both appropriately, you must understand how much your customer is willing to pay, what it costs you to provide, what investment is involved, and the return required by the financiers of that investment. So let us consider each of these pricing fundamentals, and how they interact, in a little more detail.

Think!

Do you really know the full cost of your products or services? Do your selling prices absolutely depend on knowing this?