Introduction

Organizations competing on an international basis face choices in terms of resource allocation, the balance of authority between the central office and business units, and the degree to which products and services are customized in order to accommodate tastes and preferences of local markets. These choices have historically resulted in MNEs adopting either a global or domestic business model with their associated strategies.

A global strategy involves a high degree of concentration of resources and capabilities in the central office and centralization of authority in order to exploit potential scale and learning economies. Customization at the local level is thus necessarily low.

A variable domestic strategy, on the other hand, reflects a contrary view. In this situation, resources are dispersed throughout the various countries where the organization does business, decision-making authority is pushed down to the local level, and each business unit is allowed to customize product and market offerings to specific needs. By adopting such a strategy, the MNE as a whole foregoes the benefits that could be derived from centralization and coordination of diverse activities in favor of potentially greater market share leading to increased profitability at the local level.

In truth, neither of these strategies on their own will be successful in the business world of the 21st century—a business world that is moving from a primarily vertical system for creating value to a more horizontal value-creation model. Indeed, Sir John Rose, former CEO of Rolls-Royce plc, whose company services customers in more than 120 countries through a global network of research, service, and manufacturing workers was very clear about this. In the United Kingdom, Rolls-Royce plc is considered a British company but in the United States they are an American company, in Singapore, they are a Singaporean company, and in Germany, they are a German company.1 So much so that he was once asked to accompany German Chancellor Schroeder on a visit to Russia to secure business for German companies.2 They are truly a transnational corporation.

Just what is meant by a transnational corporation? It is an MNE that embraces a model that represents a compromise between local autonomy and centralized decision making. In so doing, the organization seeks a balance between the pressures for global integration and the pressures for local responsiveness. It achieves this balance by pursuing a distributed strategy that is a hybrid of the centralized and decentralized strategies.

The Transnational Organization

When employing a transnational strategy, the goal is to combine elements of global and multi-domestic strategies. A transnational strategy allows for the attainment of benefits inherent in both global and multi-domestic strategies. The overseas components are integrated into the overall corporate structure across several dimensions, and each of the components is empowered to become a source of specialized innovation. It is a management approach in which an organization integrates its global business activities through close cooperation and interdependence among its headquarters, operations, and international subsidiaries, and its use of appropriate global information technologies.

The key philosophy of a transnational organization is adaptation to all environmental situations and achieving flexibility by capitalizing on multidirectional knowledge flows in the form of decision reasoning and value-added information, and two-way communication throughout the organization. The principal characteristic of a transnational strategy is the differentiated contributions by all its units to integrated worldwide operations. As one of its other characteristics, a joint innovation by headquarters and by some of the overseas units leads to the development of relatively standardized and yet flexible products and services that can capture several local markets. Such an approach means that decision making and knowledge generation are distributed among every unit of a transnational organization.

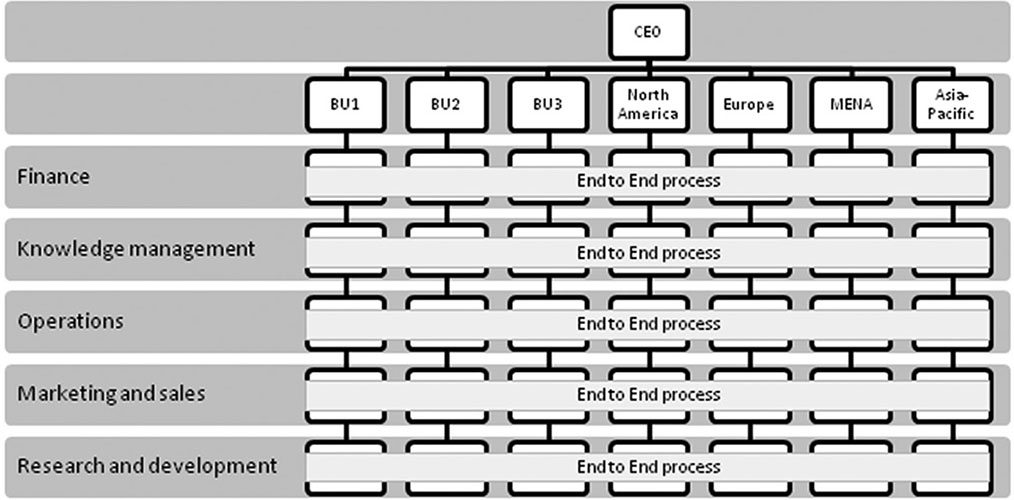

Utilizing the old adage that structure follows strategy, any transnational strategy must be supported by an appropriate structure in order to effectively implement the strategy. Just as the transnational strategy is a combination, or hybrid strategy, between global and multi-domestic strategies, the organizational structure of firms pursuing transnational strategies is a matrix one that draws on characteristics of the worldwide geographic structure, the worldwide product divisional structure and the worldwide support structure as depicted in Figure 4.1. The combination of mechanisms needed is somewhat contradictory, because the structure needs to be centralized and decentralized, integrated and nonintegrated, and formalized and nonformalized. But organizations that can successfully implement this strategy and structure often perform better than those pursuing only multi-domestic or global strategies.

Figure 4.1. An example of a transnational organizational structure.

A transnational model represents a compromise between local autonomy and centralized decision making. The organization seeks a balance between the pressures for global integration and the pressures for local responsiveness. It achieves this balance by pursuing a distributed strategy, which is a hybrid of the centralized and decentralized strategies. Under the transnational model, an MNE’s assets and capabilities are dispersed according to the most beneficial location for a specific activity. Simultaneously, overseas operations are interdependent, and knowledge is developed jointly and shared worldwide.

Think!

How would you categorize your organization? Is it simply an MNE or would you consider it to be transnational?

One organization that appears to be successfully implementing a transnational strategy by making centralization decisions based partly on whether value-chain activities are upstream or downstream is Nestlé. During an interview with Suzy Wetlaufer, Nestlé’s Chairman and former CEO, Peter Brabeck was sure that “the closer we come to the consumer, in branding, pricing, communication, and product adaptation, the more we decentralize. The more we are dealing with production, logistics, and supply-chain management, the more centralized decision making becomes. After all, we want to leverage Nestlé’s size, not be hampered by it.”3

From this simple understanding of a transnational organization, it is clear that they are prime candidates to suffer significant transfer pricing conflict. Furthermore, policy statements or pricing models, or perhaps even both, need to be embedded in their business strategy to limit the possibility of conflicts that are likely to have a significant detrimental effect on organizational performance.