CHAPTER 8

Cross-Cultural Conflict and Conflict Resolution

Contextualizing Background Information

Hellriegel, Slocum, and Woodman1 have defined “conflict” as follows: “Any situation in which there are incompatible goals, cognitions, or emotions within or between individuals or groups that lead to opposition.” This definition allows the anticipation of a few potential areas of complexity that would certainly become more acute when conflict takes an intercultural dimension.

Incompatible goals can certainly cause disruption within a business setting, but when people involved in the conflict are from different cultural backgrounds, such disruption can rapidly escalate. Reasons for greater confusion can include the fact that it may become more difficult to make goals compatible, but also because the ranking of the goals may be different and so could the notion of goals themselves.

For instance, whereas the main goal of a series of meetings could be in the mind of a Chinese negotiator the setup of an appropriate arena of interactions that would ensure proper exchanges for the future, the aim of the same negotiation for an American counterpart could be the closing of a unique deal. The difference between a synchronic and a sequential culture in this case becomes rather important and obvious, and it could lead to misunderstandings, frustrations, arguments, and the end of a potentially profitable business deal. In this case, it could happen that even if the American negotiator states the objectives clearly and makes numerous attempts at underlining his position with clarity, still the Chinese partner would not pay attention to them; in fact, he or she would actually assume the Americans ought not to rush into agreements without a complete overview of the background conditions. Any other sort of behavior would be considered unwise.

Differences in cognitions could certainly present challenges as well and at many levels. Executives from high power distance cultures would prefer not to delegate much to their subordinates, so when dealing with partners of the same hierarchical level from low power distance cultures, the amount of information they would have in hand or even have access to would be much more limited. Besides, if the former negotiators are from a high uncertainty avoidance culture, then they would also deny their ignorance on certain specific aspects, which would make matters much worse.

In terms of differences in emotions, businesspeople from emotional cultures would have a tendency to express their feelings very openly, which could distract partners from neutral cultures, puzzling them, irritating them, or even making them misunderstand what the real issues are. Neutrals could seem rather cold to emotional business partners and their distance could be interpreted as lack of interest, nonappreciation of the concessions made or dislike of what is being offered, including the warm hospitality that emotional people usually offer to foreigners they deal professionally with.

If besides being emotional, the business partners in question are also diffuse, then an attempt at separating business from private feelings of friendship or loyalty could seriously vex them. And if on top of being emotional and diffuse, the businesspeople in question are also from high context cultures, it would then probably become very difficult to understand why they react in a very angry manner when there are attempts to “get to the nitty-gritty.”

Situations of conflict that may arise when individuals involved come from different cultures (again according to Hellriegel et al.) include:

- Goal conflict: a situation in which desired end states or preferred outcomes appear to be incompatible.

- Cognitive conflict: a situation in which ideas or thoughts are perceived as incompatible.

- Affective conflict: a situation in which feelings or emotions are incompatible. That is, people literally become angry with one another.

Below are some examples of cultural misunderstanding that could easily lead to conflict because of differences in thinking, feeling, and expressing ideas in different cultures. The following passages illustrate some of the potential areas of misunderstanding:

Passage I

PETE: |

Did you talk to the accreditation body from the UK? How did it go? |

THERESA: |

Yes, sure I had to. But it went really well. What a bunch of gentlemen! So polite and sophisticated! |

PETE: |

Did you really tell them that we would not be able to deliver all the figures they are asking for by the end of the week? |

THERESA: |

Of course, I told him that we just did not have all the materials in hand and that some of the issues were just too complex for us to deal with. |

PETE: |

So? |

THERESA: |

He just said, “Oh, that is quite inconvenient, really” and changed the subject. |

PETE: |

Great! Everything is OK then. Oufff! |

In the above dialog we see a clear example of upcoming cognitive conflict, derived from a very different approach in communications. The American partners misunderstood their English counterpart, to whom the expression “that’s a bit of a nuisance” means in fact that there will be great problems caused by the forthcoming delays. After the conversation with the accreditation body, the Americans probably felt over-relaxed and will probably not make too many efforts to redress the situation immediately. On the other hand, the English will probably react quite strongly, perhaps even denying the accreditation stamp, as to their knowledge they have very clearly stated that it was not OK not to present the figures. When the Americans realize they will not have been accredited, they will be very angry with the British for not letting them know in advance that there would be penalties. The English will probably refer to the contract and avoid any sort of confrontation, while having their rights reinforced.

Passage II

MS THOMPSON: |

Are you having any sort of personal problems, Xiao Yu? I could not help but noticing that you have been sick a lot since we nominated you Head of Department. Are you all right? Is there anything we can do for you? |

XIAO YU: |

I’m sorry, ma’am. |

MS THOMPSON: |

Are you doing OK? Are there any aspects of the job that we could help you with, perhaps? |

XIAO YU: |

I would not want to be a nuisance. Thank you very much for noticing I was not feeling that well. |

MS THOMPSON: |

You have so much potential and you are so good at what you do. Far much more suited for the task than Mr. Wei or Mr. Jiao, I would have thought.... |

XIAO YU: |

Oh, no, ma’am. They are very good, and they have been here much longer than I. |

There is in this passage a clear case of goal conflict. In China, typically an ascribed country, progress and success are not measured by achievements, but through loyalty, respect for the hierarchy, and seniority. Xiao Yu sincerely must have felt in a bad position when promoted over her older colleagues, because she was put in a position in which she looks like someone who did not respect her colleagues, but who betrayed them. In a corner between doing her best at her job and losing the appreciation of her peers, Xiao Yucan only escape by faking sickness, but still, she would have preferred that her American boss had promoted one of the other employees.

In China, the objective of a career is to achieve recognition through loyalty and respect of the elderly. In America, it is to do so through performance and hard work. There is certainly a tacit conflict in this case between the American system and the Chinese one, which manifests through the loss of valuable potential hours of work and a bad office atmosphere. If on top of everything it is a young lady causing disruption, then this can be considered as a very serious affront.

Passage III

BJORN: |

Hola, Pablo, how is it going? |

PABLO: |

Very well, Sir. I was just reviewing the theory of the hierarchy of needs by Maslow with this student here. |

BJORN: |

I know, please remember I used to teach Human Resources Management before I was Dean. Actually, I overheard you; what you were telling the student isn’t exactly right. |

PABLO: |

No? |

BJORN: |

No. The security needs go below the needs for affection according to this theory. Look at the chart here, see? First basic needs, then safety needs, then... |

PABLO: |

Thank you, sir. |

Pablo has certainly felt devastated after his boss embarrassed him publicly in front of the student. Pablo is probably from a diffuse, high power distance, high uncertainty avoidance culture, and having a boss tell him how to do things is an open affront.

Pablo may have not reacted immediately, but he is certainly hurt and humiliated. He feels he is not being considered by his superior and he has lost authority over someone to whom he ought to have been seen as a role model. The long-term consequences of such an episode could escalate if this sort of scene is repeated: the employee may resign, or he may contribute to boycotting the boss, or he may find the way to embarrass the dean in another manner. But nothing very positive will come out of this interaction.

Having said this, Bjorn’s intentions were certainly good and honorable. He must have thought that his way of acting was generous and understanding. He is for sure from a low power distance culture (probably Scandinavian?) and to him, what matters is that the job gets done. Bjorn may even have thought of himself as a generous and understanding open-minded boss, who respects his employee’s rank because he asked Pablo to go to him in case there was a problem.

Solving Conflict Situations in the Workplace

In order to resolve conflict situations, structural methods of conflict management can help. Here are some examples:

- Dominance through position: Two persons or two groups are in conflict. They call a third party to make a decision that the two others will accept and respect. For example, if two CEOs of different subsidiaries in different countries disagree on a course of action to undertake, a CEO from headquarters or from a third independent subsidiary may be called upon to make a decision that the other two parties will have to respect.

- Decoupling: Avoid having people work together if they do not get along.

- Linking pins: Find people who facilitate dialog between two conflicting parties. They should be intermediaries accepted by both sides. For example, a bi-national person could help two people from two different cultures to understand each other.

Dominance through position works best in universalist cultures, because it looks like a democratic decision. In particularist cultures, on the other hand, this system would tempt the conflicting parties to try to hold the attention and benefits from the decision maker in order to apply them for their own profit.

Decoupling would probably work in diffuse cultures, and especially in high context ones, where harmony is key. As conflict in these cultures is often perceived as the major source of energy waste and profitability drain, avoiding having the parties involved meet may seem as a very reasonable choice in order to ensure harmony. In achievement cultures, such a procedure would be seen as childish and unprofessional. Workers are supposed to leave their emotions aside (in particular in neutral cultures) and concentrate in working, no matter what their issues with other colleagues could be.

Linking pins is a very commonly used technique, but more often than not it is already too late in the conflict when parties call for it. If a conflict has already been pronounced, having someone intervene can cause disruption, rather than facilitate mutual understanding. It needs therefore to be avoided in these cases. Having said this, in times when negotiations need to take place or when international parties feel they may need assistance before the conflict has gone too deep, linking pins can be very useful, in particular to reduce anxiety and have participants release tension and feel more at ease. With a lighter heart, it is often much simpler to carry on with a negotiation or to take a common action together.

The Gladwin and Walter2 Model of Cross-Cultural Conflict

The Basic Model and the Situations

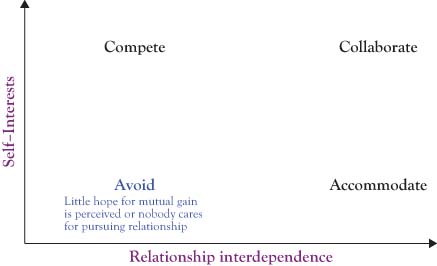

Gladwin and Walter produced a model based on the importance given to self-interest vis-à-vis the priority given to the relationship maintenance. The crossing of these two dimensions gives place to four basic attitudes towards conflict situations, which are more or less likely to appear in different cultures. The four possible options are: compete, collaborate, avoid, and accommodate (Figure 8.1).

In “compete” situations, each one of the parties involved in conflict will try to maximize the outcomes of the dispute to their own, immediate benefit. The relationship with the other side will be only limited to the one specific transaction or situation, and therefore the shared aim will be just to take as much as possible from the other for one’s own benefit at the particular point in time.

In “collaborate” situations, not only the interests of each party should be maximized, but also the relationship should be kept. Obtaining everything one party wants at one time at the expense of the other could limit potential future collaboration, therefore none of the aspects should be looked down upon.

In “avoid” situations, neither is the expected outcome worth a fight nor is the relationship worth keeping, therefore, both sides will stop the contact and with it the opportunities for opposition.

In “accommodate” situations, conflict will be eliminated through the giving away of all interests by one side for the sake of the other one involved. The main outcome of the conflict in this case, would be the maintenance of the business relationship exclusively.

The first of the four combinations, in which both self-interest and relationship interdependence are to be protected, is called “collaborate” (Figure 8.2). This option is favored by feminine cultures, which understand the need to push for achievement and progress, while they see an interest in having everyone remain happy with the outcome. For instance, in typically feminine cultures such as Sweden or Holland, disputes between management and unions often are solved after long discussions in which the interests of all parties concerned are taken into consideration.

“Collaborate” is often used as a preferred option in particularist cultures, as it is usually expected to come across situations in which the benefits of developing a lasting business relationship may exceed those of one particularly positive, but immediate business outcome. Giving favors in the present may have more important repercussions in the future, and these may compensate for an immediate small loss.

In some collectivist cultures, like in Japan, making concessions can represent a way to show goodwill in business and to expose intentions to develop a lasting and profitable relationship. This can often be perceived as weakness, but in most cases it is not the case. Giving today may just be a very polite way to signal that favors may be expected from the other side in the future.

The second of the combinations is “compete” (Figure 8.3). In this option, the contenders find themselves within win-lose situations, where whatever one does not take, the other will. Negotiators from sequential, achieving, individualistic societies are usually presented as good examples of this type of conflict management, as they do not see the point in continuing the relationship further, in particular when they need to show concrete results back home at headquarters, as they will be evaluated upon them. In “compete” situations there is always a “winner” and a “loser,” therefore it is understandable that each party will push to be on the winning side. The “pie,” or totality of assets on stake, cannot be reduced or enlarged through discussions, promises, or by “sending the elevator back,” and therefore whatever is at stake needs to be divided and it will be those who push harder that will get the most out of the exchange. It is a zero-sum game, because whatever one party will take, the other will lose.

The third combination available is “avoid” (Figure 8.4). This option is preferred by high context cultures, particularists, diffuses, and high power distance cultures because it allows to keep harmony. Particularists may decide that they are not interested in keeping the relationship alive with this partner and will avoid the conflict by stopping their dealings with him. But if they are not sure there will never be another chance for positive exchanges with them, they may chose not to openly express anger or negative feelings, but to “get away from the table” instead.

Similarly, people from diffuse cultures may estimate that this partner is not interesting or this particular deal is not worth entering into a conflict, but that having a bad rapport with the counterpart could damage their network, so they would rather not complicate the situation and go ahead just ignoring the facts and walking away.

In high power distant cultures, keeping a good relationship with the authorities may sound like utopia to most lower ranked employees. Besides, their chances of obtaining anything out of the powerful could seem impossible. Therefore, even if the self-interest is not fulfilled, many people in such a situation would deem it irrelevant to enter a discussion and would go on working apathetically, doing the minimum not to enter a conflict situation, but nothing more than that.

In the “accommodate” option one of the parties declines the totality of its interests on the matter, for the privilege of the other side exclusively (Figure 8.5). This type of behavior usually happens when there is acknowledgment and acceptance of the superiority of one side over the other (for example in the case of the buyer/seller relationship in Japan, as explained in chapter 7), typically in high power distance cultures or in high uncertainty avoidance ones, in which the fear of the outcome of the conflict could overcome the necessity to preserve one’s self-interest.

This behavior could also occur in particularistic cultures, in which a personal sense of loyalty may have developed. The sentiment of “honorable debt” vis-à-vis a partner could justify the giving away of certain rights or of certain privileges, goods, or conditions for the mere sake of pride. In many countries, the sense of honor, linked to “cleansing one’s name” or saving one’s reputation can go a long way in terms of surrendering own interests for the benefit of one cause.

Conflict Resolution and Intercultural Attitudes

When two parties confront each other from different perspectives, attempting conflict resolution from different angles, the general situation can quickly become more complicated, generating upsetting dynamics of false expectations, delusion, and disappointment.

Figures 8.6–8.11 represent potential misunderstandings deriving from the attitudes originating from diverse mental programmings and how these are received by intercultural interlocutors.

Case I: The Compete–Accommodate Misunderstanding

When one of the parties comes to the conflict mediation table with a “compete” attitude and faces an “accommodate” one, then the former will obtain everything from the latter at his expense. The “accommodating” party will just give away for a while and then probably stop dealing with the other when the cost will surpass by far the value of the relationship.

This is the typical case of the buyer–seller relationship we examined in the chapter about negotiations. The American salesperson would do his/her best to please the buyer, but the latter would ask for the moon. In France, when managers push too hard on employees, the reaction manifests through strikes and breaking of goods, even through kidnappings, but most of the time, they obey their boss without questioning his demands and requests.

Case II: The Collaborate–Avoid Misunderstanding

When one party comes to the negotiation table aiming at collaborating, but the other is just willing to avoid, the conflict can end up in different ways. One of them is that the collaborating part will get tired of trying and eventually give up on making efforts to please the counterpart. The other is that the avoiding part will take as much as is offered without giving much away, which in the medium to long run will upset the collaborating partner. In some cases, the conflict is solved by the change of attitude of the avoiding part, which at some stage may see a benefit in collaborating and give up apathy. This kind of relationship is being perceived sometimes between unions from feminine cultures who attempt at participating in decisions being made by companies with headquarters in high power distance countries. For instance, if a French company was to operate in Finland, the Finnish unions would attempt at collaborating with management, but their ideas would probably be ignored unless they make use of force at some point.

Case III: The Avoid–Accommodate Misunderstanding

When one party wants to avoid and the other is in an “accommodate” mood, the consequences are similar to the ones explained above, but to a greater extent. The interest in the relationship may be even greater for the accommodate part than was for the collaborate one because the latter has also self-interest at stake.

The case of sweatshops in India could be an example of avoid–accommodate relationship in which the boss has no interest in listening to the needs of the workers, who have no choice but to subscribe to what is imposed to them as their only means of subsistence.

Case IV: The Compete–Collaborate Misunderstanding

When one of the parties is interested in the relationship or in doing business in the future and the other is not, then the collaborative side may find it very annoying having to deal with such a partner. At first, the collaborative side may make concessions, but at some point, and because there will be no similar response from the other side, the concessions will soon end and the deal will turn into a competition, but the collaborative side will seriously start looking for alternative parties to deal with in the future and only go back to the same partner if there are no reasonable alternatives in hand.

Case V: The Compete–Avoid Misunderstanding

In cases where the compete attitude meets an avoidance one, there is rarely conflict unless the conflicting party finds a way to irritate the avoider to a point in which there is no other alternative, but to enter a dispute. When such is the case, the avoiding side will respond rather violently and attempt to end the argument as soon as possible and in a dramatic manner. In French companies, this is what often happens when an employee dares contradict a manager: at first the manager will ignore him, but after a few confrontations, and if the union does not mediate, the manager will just call for a financial arrangement or go for a lawsuit.

Case VI: The Collaborate–Accommodate Misunderstanding

When one party wants to accommodate and the other wants to collaborate, conflict will probably not last for long. It will probably be up to the collaborating side to set the rules of the game and for the accommodating side to accept them. This is the case of negotiations between Scandinavians and Japanese, where conflict often arises on communication styles rather than in content (high versus low context).

Exercise

Now discuss with colleagues and find concrete examples of cross-cultural conflict situations that you have experienced or that you have heard of and comment on them in the light of the previous exercises.