Arguments and Logical Fallacies

“We are never deceived; we deceive ourselves.”

—Goethe

“We like to be deceived.”

—Blaise Pascal

Think about how often you make propositional statements as a marketer. You may propose a new product development idea, a change in pricing strategy, or perhaps even suggest changing advertising agencies. You make these propositions because you want to increase the likelihood that your organization will be successful in the future. Let’s see how you can do this better.

Arguments

The term argument has a bit of an image problem, at least in the United States. It probably makes you think of people speaking loudly and harshly to one another. However, in the field of critical thinking, an argument is an “arrangement of statements in which one or more (premises or assumptions) are presented as evidence or support for the truth of another (the conclusion).”1 These statements or propositions have the property of being either true or false. In reality, for good arguments, these premises should be at least highly plausible for your intended audience. Example conclusions can be preceded by the word “therefore,” and take the following form: Therefore, we need to:

• Develop a new product.

• Change feature X to make our product more competitive.

• Increase our advertising.

• Increase our product research.

An argument has two basic components—the conclusion and the premises that support the conclusion. A premise is a “statement put forth as a reason for accepting the truth or reasonableness of another statement.”2 Consider the following example:

• Conclusion: Therefore, we need to begin advertising in social media to be successful.

• Premises:

◦ Social media allow us to target our advertising to those who are more likely to purchase our product.

◦ More traditional media (e.g., television, radio, and magazines) do not offer the same level of precision to identify our target consumers.

◦ Most consumers engage in social media web sites (e.g., Facebook and Twitter) a minimum of two hours daily.

The argument above is stronger than the following one, which uses a kind of false logic called “begging the question:”

• Conclusion: Therefore, we need to begin advertising in social media to be more successful.

• Premises:

◦ Today, all successful companies use social media.

“In an argument that begs the question, the conclusion that you want to prove [We need to begin advertising in social media to be more successful] is also used as a premise [all successful companies use social media].”3 It’s a kind of circular reasoning.

Many people, and I count myself guilty in this respect, often use the phrase “that begs the question” colloquially to mean that a statement someone made raises another question. Someone might say, “We need to spend more money on advertising in social media,” to which one may respond, “But that begs the question as to whether we should be spending any money on social media at all.” The correct response in this situation would be, “But that raises the question as to whether we should be spending money on social media at all.”

Begging the question is an example of what is known as a kind of “logical fallacy,” and it is in our best interests as successful marketers to keep them from sneaking into our arguments. We will review several more examples of logical fallacies toward the end of this chapter. Now, let’s look at how to strengthen your arguments by examining their structure.

Analyzing Your Arguments

One tool that can help you analyze arguments so that you can think more scientifically and make them more convincing is called “standardization.” It is a technique designed to make arguments more coherent. Reflecting back on Chapter 9, Coherence, you will recall that the more persuasive your arguments are, the more coherent and truth-conducive they will be. Standardization identifies the component parts of an argument and examines how well these components are related to each other and support your recommendation. Below are the initial steps and guidelines you need to standardize your arguments:

1. State your conclusion first so your audience knows what you are trying to prove.

2. Then, state your premises.

• Your premises should be credible to your audience

◦ When you think about it, this is only logical, because you are giving your audience reasons to believe a conclusion.

◦ A premise that is less credible than a conclusion, in the minds of your audience, cannot help you justify an argument.

An Example

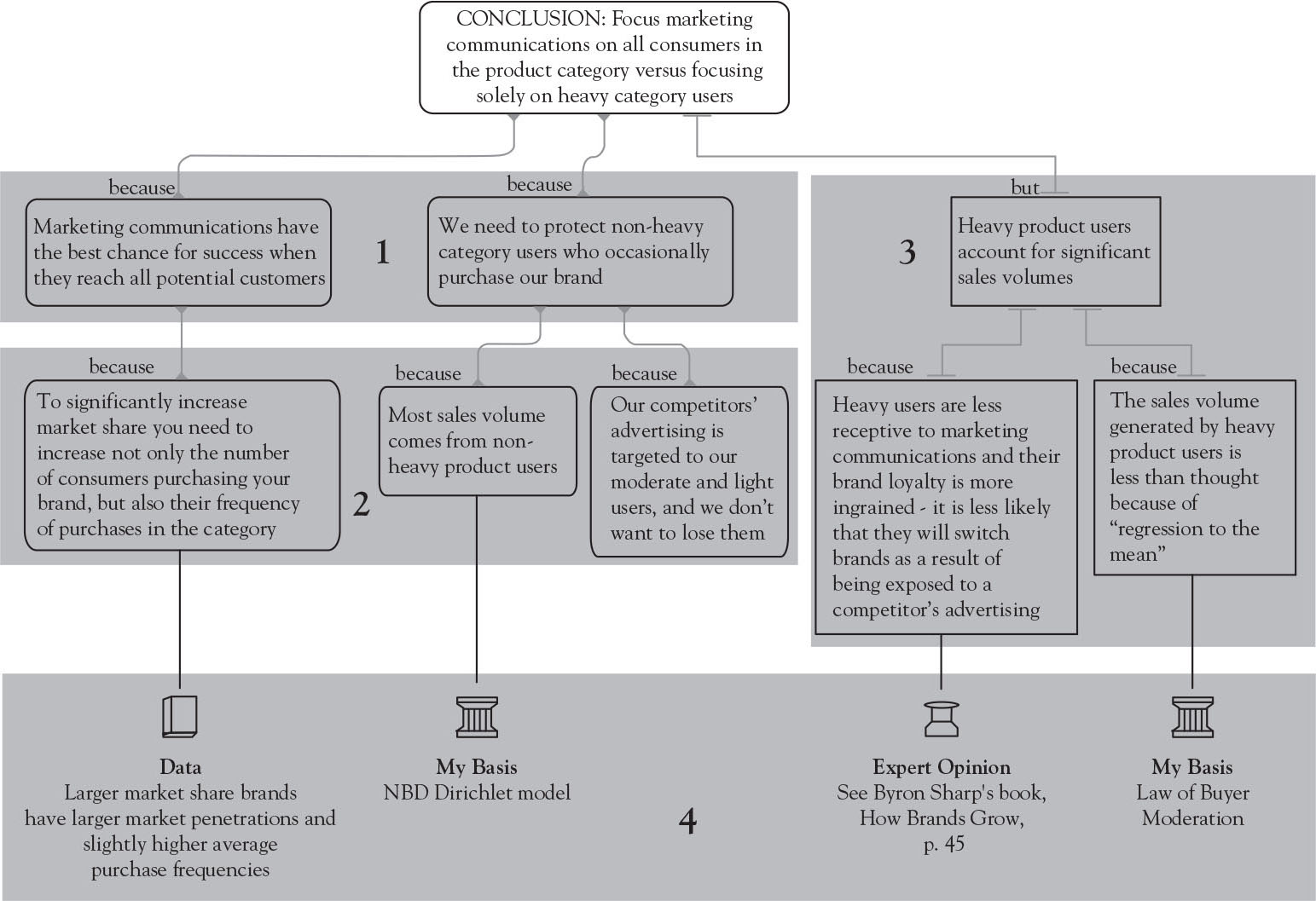

Let’s work through a simple example. Refer to Figure 11.1, which is based on Byron Sharp’s book, How Brands Grow, Chapter 4, “Which Customers Matter Most?” The context of the example is a frequently purchased consumer product that you might find in a grocery store or at Wal-Mart. (I used Austhink’s “software for visual thinking” in preparing this figure, which is available at http://austhink.com/)

Figure 11.1. Hypothetical example of an argument.

The example revolves around the merits of directing the product’s marketing communications to all consumers in the product category as opposed to developing and targeting them to “heavy” category users—a very common decision faced by marketers. The terms “heavy,” “moderate,” and “light” users refer to how much of the product is purchased over a given period of time—heavy users purchase proportionately more products during a given period than moderate or light users.

The focal point of this argument—“Focus marketing communications on all consumers in the product category versus focusing solely on heavy category users”—is the argument’s conclusion and it sits atop the figure. Beneath the conclusion are the argument’s (1) premises, (2) subpremises (premises that support other premises), (3) counter-arguments, which contain a premise and subpremises, and (4) “basis icons” showing how these sources support the various premises. The counter-argument (3)—denoted by the box labeled “but”—is “a refutation; an argument offered against another argument.”4

Many marketers subconsciously try to use the above format to build their case around a marketing recommendation. However, many never have had a formal course in critical thinking, which covers the principles of logical argumentation and argument standardization. Learning how to standardize your arguments will likely make your recommendations more persuasive and logically sound.

Argument Structure

As you move from the top to the bottom of this figure, the premises change from general to specific. For example, the premise, “We need to protect nonheavy category users who occasionally purchase our brand,” is more general in content than its subpremise, “Our competitors’ advertising is targeted to our moderate and light users and we don’t want to lose them.” Additionally, the topics covered in a “vertically” related set of premises or subpremises are mutually exclusive. For example, the proposition in the premise, “Marketing communications has the best chance for success when it has the greatest reach …” is different (mutually exclusive) from the proposition in the other premise, “We need to protect nonheavy category users who occasionally purchase our brand.”

Premises

Now let’s turn to the structure of the premises—the boxes labeled “because”—and examine how they are logically connected to each other. Each major premise (the premise boxes located immediately under the argument’s conclusion) supports the conclusion and, in turn, is supported by one or more subpremises, and a basis icon. Notice how you can begin with a major premise and logically move down to a subpremise via the conjunction because. Conversely, you can begin with a subpremise and move up to the premise it supports with the conjunctive adverb, therefore, or the phrase, as a result of this, and the connection should sound logical.

Basis

To the extent possible offer independent support to your premises. In Figure 11.1, I have referenced four different kinds of support:

• The “Data” icon states that “Larger market share brands have larger market penetrations and slightly higher average purchase frequencies.” These data could come from your company’s internal marketing research department or through an independent research company such as Nielsen.

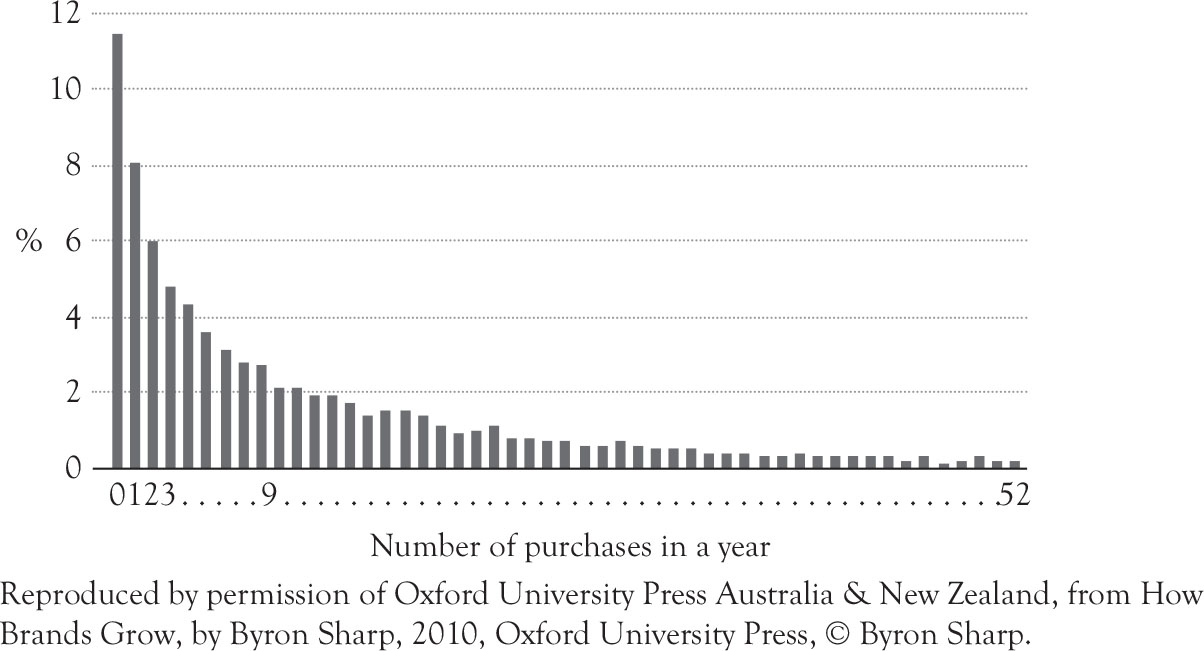

• The “My Basis” icon refers to the Negative Binomial Distribution (NBD) Dirichlet model, which shows the relationship between (1) the percentage of time a product is purchased over a given time period, and (2) the number of product purchases during that period. See Figure 11.2 for the NBD distribution of the percentage of U.S. households purchasing Coke x times in 2007. “NBD seems to describe the purchase frequencies of all brands, and has done so for decades (it was discovered in 1959 by Andrew Ehrenberg). The NBD is typically a much skewed distribution with a ‘long tail’ (i.e., “there are many more buyers who are lighter than the average buyer).”5

Figure 11.2. Percentage of US households purchasing Coke x times, 2007.

Source: Nielson.

• The “Expert Opinion” icon can refer to research conducted by an expert in a given field. In addressing the counter-argument above that icon, I reference Sharp’s book.

Counter-Arguments

Generally, in developing an argument, you can strengthen your case if you address expected counter-arguments to your conclusion. In the preceding example, the counter-argument is that our marketing communications should not ignore heavy category users because they account for significant sales volumes. Two rebuttals are given, denoted by the boxes with the label “because” in Section 3 of Figure 11.1. One references Byron’s book, the other the “Law of Buyer Moderation,” which says that “In subsequent time periods heavy buyers buy less often than in the base period that was used to categorize them as heavy buyers. Also, light buyers buy more often and some non-buyers become buyers. This regression to the mean phenomenon occurs even when there is no real change in buyer behavior.”6 In other words, heavy buyers are not as heavy as they appear, and light buyers are not as light as they appear. By expanding the time period in which heavy and light buyers are defined, the percentage of heavy buyers declines and that of light buyers increases.

Implied Premises

Finally, avoid implied premises that are important to your argument. For example, in the previous example, the subpremise, “Our competitors’ advertising is targeted to our moderate and light users,” implies that the media habits of your product’s moderate to light users is aligned with your competitors’ media choices. We could strengthen this premise by citing research that supports this proposition.

Developing Strong Arguments

In summary, the following are some pointers regarding how to structure and strengthen your marketing arguments to make them more compelling.

Strengthening Your Arguments

• Start with your conclusion.

• Support your conclusion with premises that are plausible to your audience.

• Additionally, your premises “must be relevant to proving their conclusion and they must be sufficient”7 (i.e., comprehensive) to persuade your audience. This fulfills the “truth condition” of argumentation.

• Formalize the process and make it visual—use the flow charting process.8 If this is not practical, standardize your arguments by outlining them on paper.

• Where appropriate, support some of your premises with subpremises.

• Test whether your premises and subpremises are logically linked by doing the following:

• When you read down from a premise to a subpremise, use the subordinating conjunction, “because”—the connection should sound logical.

◦ When you read up from a subpremise to a premise, use the conjunctive adverb, “therefore”—the connection should sound logical.

◦ Guard against using logical fallacies such as “begging the question” to link a conclusion to a premise or a premise to a subpremise (I address the topic of logical fallacies in the next section).

• Do your homework: “Are any important premises missing?”

• Offer independent support of your premises.

• Use counter-arguments to address premises that your audience may offer as an objection.

• Avoid implied premises if they are critical to making your case.

• Finally check yourself: Assume your premises are plausible. Do they support your conclusion? Is this support strong or weak? Can you make your argument stronger? Then ask, “Are my premises indeed plausible?” If so, you have made a cogent inductive argument—your logic is “sound” and your premises are “plausible.”

“Top 10” Logical Fallacies Used in Marketing

Earlier, we covered the logical fallacy, “begging the question,” and I warned against using it as a premise to support an argument. Generally, a logical fallacy is a non sequitur, which is Latin for “it does not follow.” Therefore, a non sequitur is a statement that does not follow good reasoning supporting an argument’s conclusion. There are literally hundreds of other logical fallacies and they are sort of fun to peruse. Have some fun at http://www.fallacyfiles.org/.

What I have done below is to select those that I have personally witnessed in my years as a marketing consultant, and I caution everyone to avoid using them to support a marketing argument, or to critique the arguments of others. The lesson of each logical fallacy is to judge an argument on its merits, and nothing else.

1. Ad Hominem (personal attack): A person’s idea is discredited by attacking the person. How often have marketers discounted ideas that come from the sales force by saying, “Those people in sales don’t know anything about marketing!”

2. Appeal to popularity: A suggestion is supported because “everyone is doing it.” How many times has a marketing manager said something like, “We need to run an ad in Magazine X because our competitors do”?

3. Fallacist’s Fallacy: An argument’s conclusion is rejected because the premises supporting it are found to be false. This does not mean, however, that other premises might be formed to support the conclusion. An initial premise suggesting that adding a new feature to a product may increase repeat purchases among current customers and thereby increase market share—a conclusion to an argument—may be proven false, but the strategy may work in attracting first-time customers to the product, thereby increasing market share and strengthening our argument.

4. Appeal to Tradition: I’ve worked with some companies that have not changed their metrics for evaluating new product concepts in decades because “we’ve always done it that way.” This position is taken in spite of new product concept testing procedures that have been shown to be more valid than conventional methods.

5. Appeal to Authority: If an idea comes from a respected source—an “authority”—it’s deemed to be credible. This is a difficult logical fallacy to manage. On the one hand, we all look to authorities for new ideas; yet, we all have heard stories about companies being “burned” by authorities (e.g., management not accepting a study finding from a marketing research firm because it is not credible; hearing conflicting points-of-view from different consultants). We need to question and investigate an authority’s advice as opposed to blindly accepting it.

6. Appeal to Novelty: An idea is embraced because it is new. Most of us receive e-mails from consulting companies, business periodicals, and associations with the “latest and greatest” “flavor of the month” ideas. I received one recently that talked about how to use “Strategy Maps.” Ask yourself: “How many of these novel ideas last and eventually make their way into respected textbooks on marketing management and strategic planning?” From my perspective, being in the marketing business for 35 years, few of the “latest and greatest” methods last beyond five years. In contrast, the methods of logic that I discuss in this book originated with the Greeks; and the concepts surrounding my discussion of the development of theories began in earnest in the late seventeenth century.

7. False Dilemma: This is when a person is forced to choose between two options, when there is an additional option (or more) possible. For example, you don’t have to choose between developing marketing communications for either traditional or social media—you can likely incorporate a blend of both.

8. Arguing from Ignorance: This fallacy is based on giving credence to a proposition that is not known to be false. Most companies do not conduct experiments on the effectiveness of their advertising; therefore, its “effectiveness” has never been disproven. This, then, is given as evidence that advertising and/or marketing budgets should either be held constant or be increased. Over the past decade, senior management’s increasing demands that marketing prove its ROI has diminished marketers’ penchant for using the Arguing from Ignorance fallacy in order to have their budgets automatically approved. Most marketing activities can, in varying degrees, be measured for their effectiveness. In this light, I recommend Douglas W. Hubbard’s book, How to Measure Anything.9

9. Subjectivist Fallacy: This “is committed when someone resists the conclusion of an argument not by questioning whether the argument’s premises support its conclusion, but by treating the conclusion as subjective when it is in fact objective. Typically this is done by labeling the arguer’s conclusion as just an ‘opinion’, a ‘perspective’, a ‘point of view’, or similar.”10 We in marketing have experienced the Subjectivist Fallacy when trying to promote the marketing concept to some senior executives with engineering or accounting/finance backgrounds. Many of these C-suite executives pooh-pooh objective research that shows marketing-oriented companies are indeed more successful and profitable over the long run than product- or sales-oriented companies.11 “That’s just their opinion,” is the common retort I’ve heard. In fact, these “opinions” are quite often factually based and the results published in respected, peer-reviewed journals.

10. The Baffle-You-With-Numbers Argument: In this example, I will level a critique at my own industry, marketing research. Researchers are known for their super-sophisticated analysis methods and reams of data tables. You should know, however, that in many industries, these research methods have not been tested for their ability to predict actual consumer choices. This is especially true with respect to questions on surveys that purport to measure how influential a product attribute is in affecting brand selection. What consumers say influences their brand choice, and what actually does influence it, can often be two different things.

Thinking Tips

David Tabor at Tabor Consulting has come up with a thought-provoking list of logical fallacies unique to marketing.12

Clueless Customers Marketing: Nobody seems to know they need our product yet

- Have you fallen victim to The Innovator’s Dilemma? (e.g., Are you innovating faster than the customers’ ability to absorb new technology? Have you gone way beyond real peoples’ requirements?)

- Do enough people really have the problem?

- Can you afford to educate the market that isn’t even aware of its pain yet?

“No There There” Marketing: There really isn’t a market here.

- Are there really buyers and sellers with consistent preferences and buying patterns?

- Or are there really only sporadic flashes of need and one-off demand?

- Can you afford to wait for a market to form?

The Customer Is Me Marketing: I can see a need for this, so there have to be customers.

- You’ve noticed this problem that nobody is solving ... .

- Does anybody else identify this as a problem?

- Have you talked with prospects about how they solve the problem today?

Size Doesn’t Matter Marketing: Microsoft can do it; so can we.

- Will customers find you credible, and what will force them to follow you?

- Do you have the technological fire power?

- Do you have the overall resources, and the will to bet everything?

Next-Generation Marketing: For people who’ve gone beyond the market leader, we’re the next step.

- Is the market leader really asleep at the wheel?

- How long would it take for them to extend their product?

- How many people are really frustrated with the current generation product?

Broken Watch Marketing: Nothing is as powerful as an idea whose time has come.

- Nothing is as pitiful as a market whose time has passed.

- Was your market doing great, and then went flat-line?

- Why must the market demand come back?

Avis Marketing: We’re going to clone the success of Cisco/Veritas/Oracle ...

- Does your market leader really have a clone? Does your market want one? (Hint: no)

- Can you duplicate their total solution? Their perceived value?

- Can you duplicate their people, technology, timing, and luck?

Vegetarian Soccer-Playing Lesbian Marketing: We’re going very narrow and deep.

- Why have you overconstrained your customer definition?

- Are there product limitations that severely narrow its application?

- Are there going to be enough customers for your use-case?

Boutique Commodity Marketing: “We specialize in all cars, foreign and domestic.”

- Are you really specialized or are you good enough at a lot of things?

- What do customers believe you are good at?

- What kind of customer would you say “no” to?

We’ll Make Money Competing With Standards/Open Source/Gorilla Platforms Marketing

- Is your product 200% better or more powerful than the commodity?

- Why will people use your product?

- What political/cultural obstacles would your product face?

Incomplete Marketing: A feature equals a product equals a value proposition.

- Is your product really a product, or a feature of something more useful?

- Is your product really an accessory to other products?

- Is the rest of your company (business model, sales support) up to snuff?

Somebody’s Got to Need What I Make Marketing

- What problem does What-You-Make solve?

- Who has this problem, really?

- Why would they pay you to solve it?

Instant Repositioning Marketing: We need to reposition without changing our product.

- On what basis should the market believe something new about you?

- Why have customers stopped buying?

- How will you erase your current position from the market?

Field of Dreams marketing: If we build it, they will come.

- If you build it, will they care?

- Exactly who is the customer?

- If they come, is it a profitable business?

First Mover Advantage Marketing: Can you say “bubble”?

- Is the advantage being there first, or being big first?

- How long can you stay that far ahead?

- Do mainstream buyers buy the first-to-market?

20% Better Marketing: My mouse trap will be 20% better than Victor’s.

- Along which performance/value angles do customers really care whether it’s better?

- Is 20% enough, or is 200% better all that will make a difference?

- How long would it take the incumbent to get 20% better?

New Category Marketing: We’ve defined some obscure area where we are the leader.

- Has nobody but your CEO ever heard of this area or the terminology you use?

- Do any analysts or press think of this as a valid market space?

- Even if it’s true, does it sound fake? Does any customer care about your differentiation point?

- Can you afford the costs and delay of creating a new market category?

Chapter Takeaways

1. When making marketing recommendations, structure your recommendations in the form of an argument containing a conclusion and the premises supporting your conclusion.

2. Insure that your premises are plausible to your audience, because you are using the premises to persuade your audience to accept your conclusions.

3. Additionally, your premises should be relevant (i.e., logically relate to) and sufficient to support your conclusion.

4. When preparing a Power Point presentation or written memorandum outlining your marketing recommendations, standardize your argument in outline form—then prepare your presentation or memo. Standardization identifies the component parts of an argument and examines how well these components are related to each other and support your recommendation. Austhink.com has an excellent software package to help you automate this process.

5. You should be able to connect your premises with your supporting subpremises with the word, because, and this connection should make logical sense. Conversely, you can begin with a subpremise and move up to the premise it supports with the word, therefore, or the phrase, as a result of this, and the connection should sound logical.

6. The most general premises—the ones “closest” to your conclusion and supported by subpremises—should be mutually exclusive in the sense that they discuss different issues. As you move “down” from general premises to subpremises, the focus of the premises should become more specific in content.

7. Use counter-arguments to address likely objections to your conclusion.

8. To the extent possible, try to support your premises with independent sources such as industry experts or statistical data.

9. State all important premises supporting your conclusion. Avoid implied premises.

10. Don’t use logical fallacies to support an argument.

11. Test your arguments. Assume that your premises are true. Do they convincingly support your conclusion? If so, your argument is “strong.” Think about how you might make your arguments stronger. Can you add more premises, subpremises, counter-arguments, or bases for your premises? You don’t want to make “weak” inductive arguments. If your argument is strong, then ask yourself if your premises are plausible. If so, your argument is “cogent.”