To Blow or Not to Blow the Whistle, That Is the Question

Introduction

Although the term whistleblowing has been known since the Middle Ages, recent economic crises and corruption scandals that resulted in the collapse of such giants as Enron, WorldCom, and Tyco have caused a reexamination of this concept in both scientific research and managerial practice.

Despite the fact that in the 1980s extensive research was conducted on this phenomenon,1 recent years are replete with research from across the world that focuses on the essence and effectiveness of this mechanism. The ACFE’s 2012 Report to the Nations on Occupational Fraud and Abuse states that 43.3% of abuses are revealed through tips—information from employees (50.9%), customers (22.1%), and anonymous persons (12.4%). Much more effective tools of abuse detection include the managerial supervision/review (14.6%) and internal audit (14.4%).2 Thus, whistleblowing is a tool for abuse detection regardless of the region or organization’s size. In organizations that use hotline solutions, abuses are detected by tips even more often in 50.9% of cases. Moreover, their implementation results in the increase of abuse detection effectiveness by the internal audit function (16.3% vs. 12.8%).3 In total, whistleblowers helped to detect nearly one-fourth of analyzed cases of abuse.

In North America, 96% of companies using whistleblowing systems recognize them as effective. In Europe, it is 78% of companies, in Africa 74%, and the global result is that 81% companies perceive this mechanism as the effective one. What seems to be especially important is the fact that, according to the research conducted in the United States, corporations that use whistleblowing systems receive sevenfold return on capital invested in these systems.4 Lawsuits involving whistleblowers are also effective, and the costs of investigations bring of the thirteen times higher return.5 The research also confirms that the most popular anticorruption practice among the companies from Global Fortune 500 (2008 Index) is whistleblowing,6 which in fact can benefit a company in terms of productivity and corporate growth by inhibiting internal corruption.7 Unfortunately in Poland, those statistics are not so optimistic, as revealed through comparison results for Poland presented by Piotr Hans in his blog.8

But what is whistleblowing, and what are its characteristics?

1. Definition and Types of Whistleblowing

The whistleblowing phenomenon is being discussed and considered in research of both legal and social sciences representatives. One of the most popular definitions that is often used in research9 describes whistleblowing as “the disclosure by organization members (former or current) of illegal, immoral, or illegitimate practices under the control of their employers, to persons or organizations that may be able to effect action.”10 On the other hand, on the websites of Transparency International (TI) we can find the following definition: “The disclosure of information about a perceived wrongdoing in an organization, or the risk thereof, to individuals or entities believed to be able to effect action.”11

In the literature of the subject we can find whistleblowing classified into autonomous whistleblowing and legally backed whistleblowing. The first one refers to the human nature and is treated as an autogenous and independent social phenomenon. It is a spontaneous disclosure of irregularities, not only when they affect the safety of the employee but also when they threaten the wider social environment.12

Practical experiences confirm the thesis that early disclosure of irregularities enables a business to identify and eliminate the problem, prevent harm or minimize damages that have already occurred, and diagnose not only abuses but also other problems occurring in a company.13 Those findings became an inspiration for the concept of enhancing whistleblowers’ attitudes in companies by14

• application of the appropriate law;

• application of stimulus such as rewards for whistleblowers—at least balancing the negative effects (like retaliation, infamy, etc.) of such a decision;

• creation of infrastructure that enables someone to inform about irregularities to corporate governance entities in an efficient and unambiguous way.

Legally backed whistleblowing exists if an infrastructure enables a person to inform about irregularities in an efficient way and verify this information while supporting that person in a possible lawsuit.15 As in the case of some managerial practices, we should be aware of the fact that existing legal provisions, as well as certain social instruments, are not perfect, and people who act in good faith and care for common goodness by revealing the irregularities or unethical behaviors can be exposed to mob mentality, loss of employment, or professional exclusions.16

Another criterion for whistleblowing classification was inspired by the United Kingdom within the Public Interest Disclosure Act. Based on this document, we may categorize whistleblowing into internal disclosure, external disclosure, and public disclosure. If irregularities are revealed inside an organization and discussed only within it, that is an internal whistleblowing. When suspicious irregularities are reported by an organization’s member outside the organization (to the appropriate entities) while omitting the appropriate persons or units of his or her own organization, that is an external whistleblowing. Public whistleblowing occurs when both the employer and the appropriate entities of supervision have been deliberately omitted and the problem of observed irregularities is presented to the mass media, for example, in order to disseminate this information broadly and to attract public attention.17

2. Whistleblowing as the Tool of Fight with Irregularities (Unethical Behaviors) in Poland

In Poland, the phenomenon of whistleblowing is not as well known, and is applied less frequently than in other countries. It is not connected with a lower rate of abuses occurring in Poland. It is quite the opposite. Similar to other countries, representatives of executive managers and employees of Polish companies are perpetrators of numerous frauds.18 The most common frauds are employee embezzlement (theft) (35%), unwarranted purchases (33%), private purchases with company’s money (20%), unwarranted use of computers (18%), bribery (18%), conflict of interest (18%), information theft (16%), invoice falsification (15%), and nepotism occurring during the recruitment process.19 In public opinion, the most popular crimes against companies committed by managers are use of companies’ assets (cars, phones, etc.) for private purposes (38%), falsifying private travel as business trips (30%), making payments for unnecessary or fictitious services (29%), bribery (28%), and nepotism (25%).20 The above findings prove that there are many aspects that should be controlled and reported.

The limited application of whistleblowing in Poland can be seen throughout history. There is a particular mentality in Poland of tolerance for known irregularities. Despite the fact that anonymous reports are commonplace acts, they are primarily associated with malice or a willingness to hurt somebody. Actions defined as whistleblowing are automatically referred to as condemned practices of collaboration with the secret services of occupiers, SB (Security Service of the Ministry of Internal Affairs), and the political apparatus of the PRL (People’s Republic of Poland).21 The term whistleblower is disparaged as “ratfink, eavesdropper, sneak, or secret service collaborator.” With this negative association of a person and the activity connected with whistleblowing that is rooted in the history of Poland, they are not an isolated case. In fact, history is replete with the selfsame bias against whistleblowing throughout the world:22

• In China, whistleblowing through such means as corporate hotlines can have ominous overtones of the worst of the Cultural Revolution, when children were encouraged to report “illegal activities” their parents might be conducting, students were encouraged to report on their teachers, and neighbors were to report other neighbors, forming a web of suspicion throughout the country.

• In Germany, anonymous whistleblowing most obviously brings to mind brutal Gestapo tactics used during WWII and the infiltration techniques and execution tactics of the Stasi in the former East Germany.

• In South Africa, whistleblowers called impimpis, apartheid-era informants, could be put to death in public.

It should be noticed that in other countries with more grounded democracy and with different social attitudes, a whistleblower is treated with greater respect, sometimes even like a hero.23 For instance, Time magazine selected three whistleblowers in 2002 as their “Persons of the Year”: Cynthia Cooper of WorldCom, Coleen Rowley of the FBI, and Sherron Watkins of Enron.24 Despite results presented in a report by the PwC, “Global Economic Crime Survey 2011,”25 that there has been a decrease of whistleblowing effectiveness as a tool for abuse detection, there is an undeniable fact that whistleblowers have helped in detecting nearly one-fourth of the cases of analyzed abuses. Unfortunately, statistics for Poland are much worse than what is confirmed by comparative results with other countries. According to the “Global Economic Crime Survey 2011,” organizations may use the following methods to find out if a fraud has been committed:26

• “Corporate controls” including internal auditing, fraud risk management, electronic and automated suspicious transaction monitoring, corporate security, and transferring people

• “Corporate culture” including internal tip-offs, external tip-offs, and whistleblowing

• “Beyond the influence of management”—finding out by accident or through the media, for example.

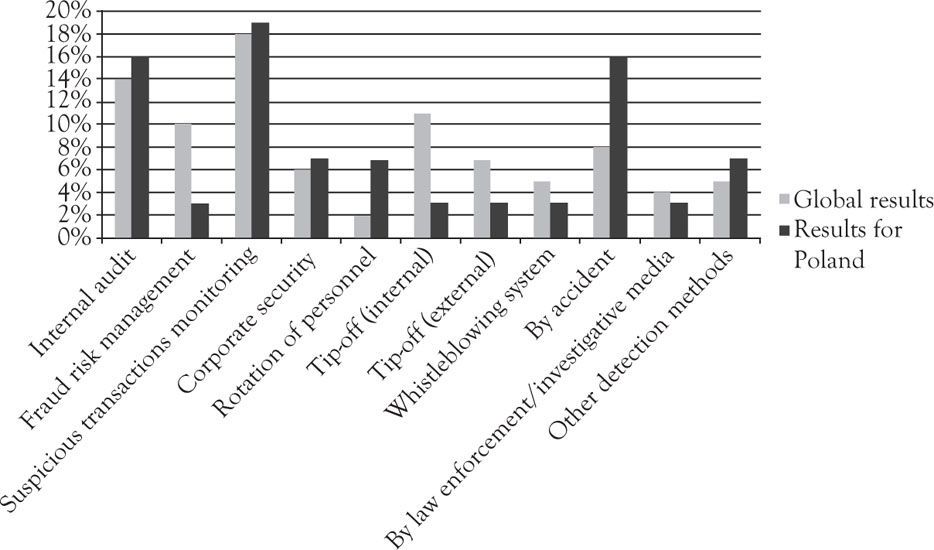

Figure 3.1 presents the popularity of those methods among companies participating in research conducted by PwC in 2011 and among Polish companies.

Figure 3.1. Detection methods in 2011—comparison.27

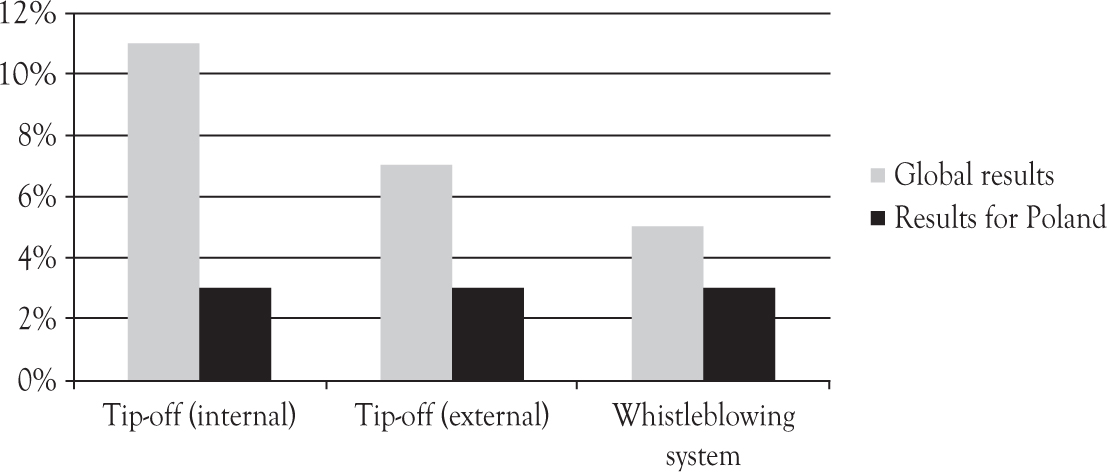

When we focus on the popularity of particular elements constituting the segment of “corporate culture,” namely internal tip-offs, external tips-offs, and whistleblowing, the difference between their use by Polish companies and by organizations analyzed by PwC is highly significant. Figure 3.2 illustrates the difference.

Figure 3.2. Popularity of corporate culture in detecting economic crime in 2011—comparison.28

As noted by Piotr Hans, the comments of PwC representatives for the Onet.pl portal as well as on websites of PwC Polska leave no illusions about the Polish specificity. Dariusz Cypner emphasizes that, according to the report, there is a lack of effective mechanisms for detection of economic crimes in Poland, and most of the abuses are detected by accident. There are no ethics hotlines in Polish companies that can be used for anonymous reporting to executives about observed abuses. Another report finds that 16% of Polish companies—twice as much as in other countries—find out about the committed crime accidentally. Fifty-two percent of crimes were detected through controlling mechanisms in companies, but only 3% from people from the outside of organization’s structure who were cooperating with another relevant group, such as suppliers or customers.29

Those results confirm the previous information noted by Rogowski in his paper. The findings of survey research of members of the boards and supervisory boards of the biggest Polish companies state that in about two-thirds of the companies there do not exist any procedures enabling employees or other stakeholders to offer early anonymous warnings by reporting any irregularities to corporate governance entities.

Is the lack of popularity of whistleblowing mechanisms in Poland and Poles’ attitude to these mechanisms a result of historical experiences, or is it caused by mistakes made during its implementation, low citizens’ awareness of such mechanisms, or fear of inadequate protection of the whistleblower? It seems that we should seek those causes in each of the mentioned phenomena.

3. The Value of Courage and the Cost of Silence; Examples of Whistleblowers from Poland

The legal protection of denunciators differs across the world. In the United Kingdom, the Public Interest Disclosure Act from 1998 about disclosure for the public interest protects denunciators from retaliation and job dismissal. In the United States, the LaFollette Act from 1912 was the first act of particular whistleblowers’ protection. This gave federal employees the right to provide information directly to the United States Congress. Currently in the United States, many laws at both state and federal levels exist that protect whistleblowers. The most important are still actualized Whistleblower Protection Act from 2007 and Sarbanes–Oxley Act from 2002.30

On the websites of Against Corruption Program (Program Przeciwko Korupcji) that runs under the Stefan Batory Foundation, we may read that whistleblowers in some countries, especially in Anglo-Saxon countries, are covered by legal protection separate from the general rules of law. In Poland, whistleblowers do not have any protection (in case of civil law agreements) nor may try to assert their claim in accordance with the code of labor. However, as there is no particular reference to whistleblowers (no specificity for this mechanism), it does not provide them with sufficient protection. The Stefan Batory Foundation in 2010 conducted research among judges of labor courts in Poland. It was aimed at gathering opinions on the effectiveness of labor law solutions for protecting the employees who revealed irregularities in good faith in their organizations. The final findings confirm that opinions collected in the survey research force us to question if the Polish legislator achieved the objective recommended by the European Council to create legal conditions that truly protect a person who knows about irregularities and is not afraid of their disclosure.31

Without an effective legal system that protects a person who reports irregularities in a particular organization’s performance, the whistleblower is always exposed to bearing the costs connected with a decision to inform a particular entity about those irregularities. Such a person is exposed to mobbing, professional exclusion, job dismissal, and ostracism. The person is perceived as a pariah who “fouls his/her own nest.”32 The price of such a decision is not typical just for Polish citizens. Many laws, including the Sarbanes–Oxley Act in the United States, the Public Interest Disclosure Act in the United Kingdom, and laws in other countries deliver protection for whistleblowers. Despite such legislation, many international employees fear repercussions.33

A decision to disclose irregularities has its consequences, but hiding in silence also has its cost. The price occurs in such forms as frustration, specific “moral hangover,” questioning one’s axiological attitudes, or a specific moral discomfort. We should remember that the fundamental characteristic of a human being is goodness. Goodness is what elevates us from animals. Moreover, disclosure of unethical and immoral behavior and opposition to them is specific to human nature. The renunciation of unethical behavior disclosure results in our participation in unethical dealings. Recent research conducted in Poland informs that among many professional groups 52% declare that they would not disclose any information. Nineteen percent of this number would be constrained by the threat of job dismissal, 14% by the lack of appropriate legal protection, and 19% by the lack of belief in the effectiveness of police and courts.34

Despite the constraints of the legal system in Poland and despite the negative association with the term “whistleblower,” there are many examples of people who act in good faith, for morality, and for higher values of protection against all odds.

For instance, Rzeczpospolita magazine described the case of Leszek G., a 34-year-old miner who, in 2009, used a camera to record the practice of falsification of the measurements of methane concentration.35 He collected proof of law violations in a Wujek-Śląsk mine in which 21 of his colleagues died. As a result, he became redundant (earlier he was forced to perform physically demanding tasks after he refused to falsify methane concentration measurements).

Another example is a Warrant Officer Dariusz Warchocki from the 56th Regiment of Combat Helicopters, who revealed that there were irregularities in training and document falsification. Finally, he decided to leave the army. In the period of notice, his supervisor prohibited him to fly and deprived him of extras to his salary.36

Dąbrowski gives the following examples of Polish denunciators:37

• Bożena Łopacka, a former manager of “Biedronka” shop (Jeronimo Martins), revealed a practice of falsifying work-time records and forcing employees to perform work that was not in the scope of their duties. It resulted in prosecution of the company as well as a lawsuit that went on for very long time.

• Tadeusz Pasierbiński, gynecologist and obstetrician, who currently works in a small medical facility in Silesia, decided to disclose corrupt practices that occurred in a hospital he used to work at. He was punished by his supervisors with numerous disciplinary sanctions. In addition, he was sued in medical court and lost his tied accommodation. After dismissal, he fought for reinstatement in his profession, fortunately with a positive result.38

Conclusion

Economic crises of recent years and numerous corruption scandals across the world severely damaged social trust in corporations and their leaders. The business world should not forget that according to Aristotle’s Nicomechaen Ethics, the purpose of a business activity is to ultimately make a manager a better person and make the world a better place.39 From an Aristotelian point of view, it is possible to simultaneously create wealth, be ethical, and be happy too.40

We should also remember that capitalism is not fundamentally an immoral and selfish system. It has been and may continue to be a flourishing economic system provided that people abide by the rules. What rules? Famed Scottish economist Adam Smith states them as follows: “Tell the truth. Keep your promises. Be responsible for your actions. Treat other as you would like to be treated—with compassion and forgiveness.”41 And be wise.

Implementation of whistleblowing mechanisms in organizations is a small step that should be taken toward the creation of a formal ethical infrastructure. Recommendations may be formulated to make whistleblowing a more effective mechanism for abuse detection. Such recommendations will be focused on making whistleblowing available via the Internet (including e-mail), keeping such activity confidential and protective for whistleblowers, available 7 days a week, 24 hours a day. Whistleblowers should be provided with the opportunity to report in their local language, ensuring anonymity. These choices should be provided by an independent organization, specifying inappropriate behaviors to be reported, providing feedback for whistleblower, and offering the possibility for whistleblowing by suppliers/customers.

However, even if an organization built this into its internal infrastructure, it would not be enough to ensure its integrity. An organization does not work in a vacuum. It requires an appropriate legal system that can effectively protect whistleblowers. In cooperation with numerous organizations, TI has prepared draft principles for whistleblowing legislation that examine existing legislation and provide a solid paradigm for international, regional, and local utilization.42

The formal ethical infrastructure as well as its external mechanism, however, cannot protect a company from wrongdoing. Each regulation, formal system, and knowledge base has its limitations. Within the process of ethical and moral decision making (behaviors of both an individual and an organization), there is only a human being with his or her knowledge experience, character, value system, moral, and social intelligence.43 That is why, as noted by Wankel and Stachowicz-Stanusch, the education for integrity is also necessary.44 This “lesson in integrity” manifests itself in structuring a moral framework applicable from the microstructures of individual job teams to the macrostructures of international business. In all cases, human beings need to be grounded in integrity, ethics, and high moral standards. They must identify corruption at all levels and choose not to live with it. It is incumbent upon business and educational systems to develop sound theoretical programs made real and practical with case studies, behavioral modeling, introspection, and analysis that harkens back to the Socratic method of inquiry, keeping a constant eye toward the greater good of humanity itself.45

The author hopes that a combination of education for integrity, the internal ethical infrastructure of organization, and effective and good laws will result in a situation whereby righteous citizens acting in righteous organizations and in a righteous environment make the world a better place for them and for their descendants.

Key Terms

Whistleblowing—the disclosure by organization members (former or current) of illegal, immoral, or illegitimate practices under the control of their employers, to persons or organizations that may be able to effect action.46

Whistleblowing—the disclosure of information about a perceived wrongdoing in an organization, or the risk thereof, to individuals or entities believed to be able to effect action (TI).

Autonomous whistleblowing—autogenous and independent social phenomenon; a spontaneous disclosure of irregularities, particularly when they affect the safety of the employee, but also when they threaten wider social environment.

Legal-backed whistleblowing—the phenomenon occurring if there exists an infrastructure that enables to inform about irregularities in an efficient way, as well as to verify this information and support in possible lawsuit.

Internal whistleblowing—a situation occurring if the irregularities are revealed inside an organization and discussed only within it.

External whistleblowing—a situation whereby the suspicion of irregularities are reported by an organization’s member outside the organization (to the appropriate entities) while omitting the appropriate persons or units of his or her own organization.

Public whistleblowing—a situation when both the employer as well as the appropriate entities of supervision have been deliberately omitted and the problem of observed irregularities was presented to, for instance mass media, in order to disseminate this information broadly and to attract a particular attention.

Study Questions

1. What activity, despite the historical circumstances of a specific community, may influence the popularity and effectiveness of whistleblowing mechanisms in a particular community or nation?

2. What influence does a national culture have on the effectiveness and application of whistleblowing in a particular community?

3. What actions may be taken by an organization in order to increase the whistleblowing effectiveness?

4. How may an organization protect itself from the “black” whistleblowing?

Further Reading

Alford, C. F. (2001). Whistleblowers: Broken lives and organizational power. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Bowers, J., Fodder, M., Lewis, J., Mitchell, J. (2012). Whistleblowing: Law and practice (2nd edition). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Cooper, C. (2008). Extraordinary circumstances: The journey of a corporate whistleblower. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Deloitte, Polski Instytut Dyrektorów, Rzeczpospolita. (2007). Współczesna rada nadzorcza 2007, raport z badań, s. 16. Available at: http://www.deloitte.com/assets/Dcom-Poland/Local%20Assets/Documents/Raporty,%20badania,%20rankingi/pl_WspolczesnaRadaNadzorcza_2007.pdf.

Devine, T., & Maassarani, T. F. (2011). The corporate whistleblower’s survival guide: A handbook for committing the truth. San Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

Freedman, W. (1994). Internal company investigations and the employment relationship. Westport, CT: Quorum Books.

Greenberg, M. D. (2011). For whom the whistle blows: Advancing corporate compliance and integrity efforts in the era of Dodd-Frank (Conference Proceedings). Santa Monica, CA: Rand Corporation.

Johnson, R. A. (2002). Whistleblowing: When it works-And why. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Pub.

Kohn, S. M. (2011). The whistleblower‘s handbook: A step-by-step guide to doing what‘s right and protecting yourself. United States of America: Lyons Press.

Kohn, S. M., Kohn, M. D. & Colapinto, D.K. (2004). Whistleblower law: A guide to legal protections for corporate employees. Westport, CT: Praeger.

Lipman, F. D. (2011). Whistleblowers: Incentives, disincentives, and protection strategies. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Miethe, T. (1998). Whistleblowing at work: Tough choices in exposing fraud, waste, and abuse on the job. United States of America: Westview Press.

Near, J.P., Rehg, M.T., Scotter, J.R. & Miceli, M.P. (2004). Does type of wrongdoing affect the whistleblowing process? Business Ethics Quarterly, 14(2), 219–242.

Westin, A. F. (1981). Whistle-blowing! Loyalty and dissent in the corporation. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Whannel, G. (2008). Culture, politics and sport: Blowing the whistle, Revisited. New York, NY: Routledge.