Chapter 8

It's Not What Happens, It's What You Do About It

Planning seldom asks, “Then what?” Yet it's precisely the “then what” capacity that gets a team across the finish line. There is always surprise. Power leadership seizes surprise as opportunity to create pride and greatness.

The power of surprise is well documented, from war to new products to death of a key player to real competition in your core market. From all the surprises documented around us, you'd expect that well-run businesses would employ surprise as a core competence and build in a defense against a surprise-rich world. We sometimes see one of these, but seldom both in the same company. It's so rare that you can immediately name the two or three firms that do both well. This, then, is an opportunity almost beyond bounds. Let's start after it.

HOPE FOR THE BEST, PLAN FOR THE WORST

This phrase now has been turned inside out. The best companies say, “Plan for the best, and hope for even better.” The problem with planning for the worst is defining what it looks like. In fact, there can be so many “worsts” that planning can't keep up. Instead, pour fuel on the plan, expecting to outrun the worst as it shows up.

Change what you plan for. Use two time horizons: known and possible. Excellence in the known is the launch pad to capitalize on surprise when it shows up.

The known plan is a low-risk adaptation of what works now: selling more to existing customers, recruiting new business in familiar markets, developing product line extensions, and so forth. This plan can be spelled out clearly enough to produce quarterly/monthly budgets, quarterly plans with daily KPIs, weekly reviews of KPIs, and core initiatives. This system, partly familiar, is still poorly executed in most companies that I see. We'll examine the two most common problems.

The Company Is the Leader

The leader built the business, has deep knowledge (of present staff, customers, processes, and opportunities), and closely controls all initiatives. This works well until it doesn't. That can happen because of growth, desire to sell the company, new leadership, and more. The core issue in that company is the leader—with his fingers in all the sockets. When too many things need to change at once, the leader falls short, often with delayed effect because many things appear to be alright.

The quickest diagnosis is to ask what will make things right. If the answer is more sales, it's time to shift to emergency mode. The business needs to expand its capacity to perform profitably and reliably and do it in many areas at once quickly. This requires a new structure that moves leadership out to new leaders with the communication systems, data systems, and sharper focus that success demands. Not big data, just data to run this business knowledgably. Competent leadership is even more scarce than adequate capital, although success takes both. The challenge is to allow change while things are still healthy.

An example (one of many) is a business (twenty-five-plus years old) run by its founder–leader. He said to me, “I've got to get my sons and son-in-law to grab this business and run it confidently and aggressively and do it now. We have a window to outrun our competition, but they don't have the confidence to step up and do it.” What's more likely based upon my conversations with the owner is that he is unwilling (unable?) to hand over leadership, even in a planned way over time. He can't see that he's now in unfamiliar territory—empowering and teaching other leaders while he steps back—and he's blocking their growth.

It's like trying to teach a person to drive a car without letting them sit in the seat. They can watch forever, but until they hit the curb turning a corner they won't grasp what it takes. The trick is to let him drive and anticipate well enough to guide him away from lethal mistakes, while letting the other errors happen. We say to ourselves that it's okay for us to make mistakes because we learn from them, hiding how much we hate our mistakes, and then deny that learning to others.

Getting this leadership growth requires investing the time in goals, budgets, KPIs, initiatives (GBKI), and more.

Partial Shift from Leader to Leadership Team

Consider what happens when a leader has partly shifted to a leadership team with GBKI. The strength is in the framework defining the boundaries (GBKI). The vulnerability is the lack of discipline in evaluating progress daily or weekly, clearly identifying next steps, and seeking responsibility and accountability outside his or her office. The form is there, but the heart and the substance are missing where the power is: in the accountability and adaptiveness over time. The power in this system is that each employee knows what she needs to get done in the coming day or week, has a way to track success or problems, and can get competent help in a timely manner. The personal ownership of both task and quality captures the enthusiasm and willingness of employees who are in jobs that they love.

At this stage, firms can improve their operations and capacity for growth if they'll work seriously on accountability. Accountability isn't avoiding mistakes or owning them, it's owning processes that produce correct outcomes most of the time. It's a mix of anticipation, hard-headed plans, and tough follow-up that relies heavily on discipline and teaching instead of fear. That almost always requires leaders and workers who seek coaching and mentoring, who love to learn, and who mostly feel safe when things go wrong and they need to get help. It requires leaders who see their jobs as enabling others to succeed by seeing that these elements are in place:

- Leadership organizational structures that are up to the challenges of the month/year.

- Real-time evaluation/decision structures that demand high payback decisions.

- The right people in the right jobs with the right skills.

Even with all of these, a “gateway” leader who needs to initiate all high-value investments will be too slow, make too many mistakes, and drive away the gifted leaders who yearn for space to try their “stuff.” With all of that, how does one convert an organization to one that excels when surprises occur? It's done by planning for the possible horizon. That is wordplay; it really means plan for surprises that you can't know in advance. How do you do that?

- Excel at GBKI—goals, budgets, KPIs, initiatives.

- Speed up introduction of new services or products, but demand excellence.

- Excel in finding weakness in new offerings and adapting to make them winners or withdrawing them from the market.

- Excel in using data to change operations. Instead of viewing each software installation as an excuse for poor performance, acknowledge that constant upgrades with excellence is a condition of doing business.

- Learn to lead when afraid! Robert Johansen, president of the Institute for the Future (a thirty-year-old Stanford Research Institute entity), posits that a VUCA world will demand leaders who can excel while overcome with fear. The uncertainty of a VUCA world means that much of the time leaders move into a dark room as they try to see what's needed in their organizations. All of us fear the dark when it likely includes danger, so that CEO fear is healthy realism. Some organizations are now using games to enhance top leaders’ skill in performing while afraid, if not terrified. The games simulate life-altering challenge, forcing players to compete at full intensity while deeply afraid of losing! If you are competitive, you can see how the right game can put you there.

THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN STRATEGY AND TACTICS

There are two common frames for strategy: time and focus. But both are defined by the essential third: What do we want to be? Time and focus are tactical but lose their power without defining what we want to be. Tregoe and Zimmerman shift the focus to “driving force,” which is the main way to decide future products and markets.1 This shift away from operations is essential to avoid the common error of increasing last year by 5 percent and calling it a strategic plan. It is neither. Pull back a minute to reestablish that a business is first about the scope of its products (services) and markets. It is only then about the business model, sales, production, and so forth.

Even more, the driving force is a necessary limit on all elements of the business, providing a lens to clarify which roads to follow, and which to ignore. The concept is slippery, but worth the capture. Driving force is the single concept that captures the unique strength of the company, helping to shed appealing ideas that are less likely to come to fruition. Tregoe and Zimmerman offer a collection of driving forces that can clarify the area that must excel for the business to succeed. It doesn't exclude others but demands that it be protected and exploited with all available vigor if success is a serious goal. These examples of driving force can be useful to help you frame your own, if you clarify to all employees their central role in your present and future success. Here are Tregoe and Zimmerman's driving forces, with examples:2

| STRATEGIC AREA (DRIVING FORCE) | EXAMPLE |

| Products offered | Ford, Bank of America |

| Market needs | Gillette, Merrill Lynch |

| Technology | DuPont, US Center for Disease Control |

| Production capability | US Steel, International Paper |

| Method of sale | Franklin Mint, Amazon |

| Method of distribution | MacDonald's, Comcast |

| Natural resources | Shell Oil, DeBeers Consolidated Mines |

| Return/profit (Return/profit determine scope of markets and products) | BlackRock, Bain Capital |

The summary is that a single driving force is a powerful frame for future company decisions, and therefore worth the effort to develop. It comes alive as a strategy, and tactics are developed to pursue it. The question “What do we want to be?” can be explained to frame every other decision, financial, tactical, hiring, expansion, choice of industry, and more.

The time approach limits strategy to a future period, usually three or five years. It uses both budgets (annual budgets for three or five years) and broad action plans to accomplish budget targets. Tactics are then the specific actions within each company department to execute the current year's portion of the three-to-five-year strategy.

The focus strategy considers broader lines of business as possibilities, such as transportation or resource recovery (mining, oil drilling, etc.). These broader possibilities are then refined within estimates of depth of opportunity, strength of competition, and the amount of capital and expertise the firm must have to be number two or number one in that business domain. Those resource estimates help to select among equally attainable strategic paths, weighting time and probability of success to refine the strategic direction. That direction then devolves into one-year and three-year tactical budgets and plans, driving related one-year department tactical plans.

The three-point perspective of Leilani Schweizer pulls actionable opportunities into the spotlight faster and with less wasted motion. Schweitzer first tried every way she could think of to change the medical system that mistakenly killed her twenty-month-old son. Finally, applying a design technique from her courses at Montana State University, she helped reduce medical errors by creating a three-dimensional perspective on medical care through the eyes of the three groups at the center of medical care: physicians, nurses, and patients. “This process bends space and time, allowing us to see an object from three perspectives with a single drawing. We need to see multiple views—from doctors, nurses, patients, administrators, and volunteers—at one time.” Only then, she said, will health-care providers understand problems fully enough to “find true, long-term solutions.”3

For your business, replace SWOT by creating a Schweitzer three-dimensional strategy perspective: Ask departments to look through the lens of opportunity and weakness at customers, competitors, and the future to produce real target products or services. It is most manageable with a two-to-three-year target, provided the contributors include senior executives and department leaders in the firm. Draft perspectives can benefit from review by a board of directors, if it has the strategic breadth to consider those possibilities. That's a nice way of saying that if your board is your dad, your lawyer, and your accountant, their contribution will focus mostly on limits rather than possibilities. At this stage, the wisdom should be about possibilities, leaving to management the task of parsing possibilities and their respective return and risk.

Tactics at their best combine operations targets with selected initiatives. Operations targets emphasize efficiency, quality, and customer service. Initiatives drive selected improvements in existing operations or launch of new products or services. Their management requires a different rhythm of measures and adjustments, as well as close involvement of different levels of management. Line teams are best equipped to find and implement operations efficiencies, pulling in technical help to frame problems at the right breadth and offer more technical solutions when needed.

The problem with becoming an efficiency-only company is, as one wag said, that you can't cut your way to growth. The real problem is near-term emphasis. Cutting expenses or boosting efficiencies is enormously rewarding, easy to measure, and easy to award recognition to folks who can see their contribution.

The alternative is to deliver new products or services while maintaining the excitement about efficiency. New anything is fuzzy, uncertain, hard to defend, and essential to health. The most courageous leaders at every level are those who have the grit (see book with the same name by Angela Duckworth) to keep at both and do it in public.

A simple diagnostic: What's new in this year's plan? If the “new” launches more than three years out, you've got challenges of focus and execution. Three years out frequently translates to “never.”

Launch of new products or services builds upon special development efforts by cross-functional teams that refine the concept of an offering to assure its customer appeal, and then refine its consistent production within the company. It sounds simple and fails often enough to justify this warning: New offerings take twice the money and three times the talent and time, and still frequently fall flat. Success comes from the inspired (“emotional”) drive of key lower-level leaders, not lofty speeches from the CEO.

LEADING THROUGH AMBIGUITY

The successful executive inbox looks like Times Square on steroids, closing at hyper speed. The urgency hides the ambiguity of impact and cost. Instead, success is the continuing skill to determine where to place the biggest resources: people, money, and time. The fog of ambiguity blocks the view past the decision room, offering wisps of insight into the future.

Deploying resources requires sizing up the future as it speeds into view and making choices about deploying those resources. Ambiguity is the inevitable partner of successful leaders. That ambiguity can be moderated with time, data, and analysis, but the fundamental uncertainty of launching into the dark room of the future remains. That uncertainty is both about the future situation outside the company, and the performance of the company as it enters the dark room. The challenge is to balance opportunity with company capability, and then determine whether the risk justifies an investment. That sounds cerebral, reeking of quiet rooms full of brilliance and insights. In fact, it's a sequence of rooms of messy ideas, incomplete analysis, personal bias, and the ticking clock of opportunity escaping.

The unspoken promise of clear decisions powered by firm alternatives just doesn't exist. The successful move forward when they have 60 percent information. Waiting bleeds opportunity dry.

So, if all is fuzzy, what are some guideposts?

- Press to see all opportunities that you might exploit.

- Upside: Roughly sort payback and feasibility, quickly. (Could we do it? If so, what do we get?)

- Downside: Compare risk and payback. (Does the payback justify the risk?)

- What's the expected value of success versus the cost?

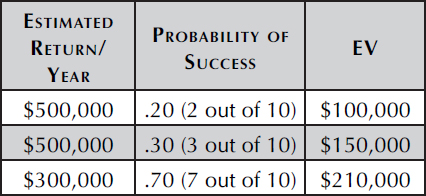

The Secret of Expected Value (EV)

Expected value is a simple way to sort options based upon risk and payback. The beauty of the approach is that rough estimates can yield excellent results. How can that be? EV works on “coarse decisions,” where the choice is about exactly where to invest resources to refine a specific approach. It lets the user engage more options faster, without the “engineer's dilemma”: The engineer–thinker wants to know how something will be done before committing to do it. The problem is that this reasonable-sounding approach deletes options that might be realized with the right investment in the “how.” It's also a way to tone down the ecstasy of a fabulous solution that's beyond unlikely but offers magical returns. High-potential returns sometimes have a way of fogging the reason. Table 8.1 displays an example of EV.

Table 8.1 Example of Expected Value (EV)

(EV is the percent likelihood of success multiplied by the payback minus the cost; return on investment is EV divided by cost, as a percent.)

The expected value takes in the possibility of failure but not the cost of it. The cost of failure may be the first measure. It's not the cost of trying, but rather the cost of the lost opportunity (opportunity cost), measured in these dimensions:

- Lost profit on lost sales.

- Lost opportunity for further revenue.

- Lost opportunity for improved efficiency at higher volume.

- Opening the door to strengthen a competitor who may then seek your existing business.

Opportunity cost can be calculated like expected value, and the EV benefit can be compared to the EV cost for a sharper picture into the future.

- Formula: Is the expected value enough greater than the opportunity cost to justify action?

- What is our capacity to recover if the investment delivers far less than planned?

This process can be cut to shorthand to surface only opportunities worthy of attention. Data will not remove the ambiguity, however, because ambiguity holds the opportunity to earn significant returns. Ambiguity is an unsolved problem. The ones who solve it well may—may—reap a reward.

The problems:

- The reward may be out of reach.

- The cost damages cash capacity.

- The diversion damages existing customer service and product quality.

- The diversion removes key employees who return to the main business too late to bring it back to health.

The first ambiguity: Should we pursue this opportunity? The second ambiguity: Can our teams execute this plan well enough to hit our goals?

Moving folks who excel in the established company to the new entity sounds appealing, but it's a double risk: They are removed from making the money that keeps the business going, and they may need the historic structure, history, and undocumented ways of doing things to be successful. It's one thing to lead an established business, even when it needs improvement. It's quite another to frame for the first time the norms, processes, measures, revenue building, margin and inventory management, and customer service systems that a successful new business requires. A common error is to understate the time and mistakes that building a new entity takes, basing that on the time it would take the existing business to accomplish these things. And the middle ground doesn't work (keep the best folks in their current jobs and ask them to produce the future).

Ambiguity extends beyond the yes/no decision to performance in the new entity. Even if all of the above is on the mark, execution over time can erode profit and will, leaving an organization tired of the task.

All of this explains why so few companies produce entirely new products and services. The swoon for growth ignores these realities, as though brains and discipline will deliver success. They seldom do. The dirty secret of venture capitalist investors is that most of their investments fail. Most. They presumably are best equipped to find the winners and guide them to success, but what of the rest of us?

For some folks, the fascination of risk and the possibility of great reward are enough to chase breakthrough businesses. For most of us, incremental growth is enough. The problem is that our competition is in the same place, so the game goes not to the inventor of the new concept but to those who execute beautifully. Apple and Microsoft are examples.

The single best way to cut the paralysis of ambiguity is relentless focus on delivering excellence. Ambiguity lives in every untried idea, even those about better execution. In fact, dramatically better execution wins most races today. The scandal of exploding auto airbags is evidence of that because the scandal is that the airbags were faulty, not that they exploded. Their explosions were dramatic and terrible, but cars are now routinely complex and virtually error-proof. That routine is the result of years of intense focus on execution.

OPPORTUNISM AND INNOVATION

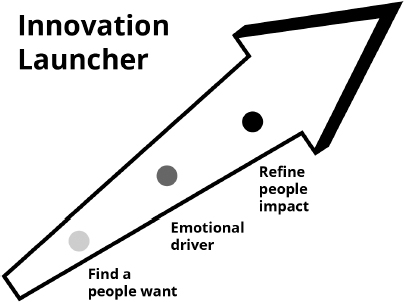

Innovation happens because people set out to find a better way. There are always two parts to the innovation process: think it up and make it work in the world.

Part A (Think it up) Innovation possibility formula:

Who finds it? + What's the appeal?

Part B (Make it work) Survival test:

Who wants it? + What do they think they will be buying?

Part C Business model:

How likely is profitable volume? When?

Until you're excited about A, skip B and C. The recycling bins are full of weak ideas that someone hoped would rise from the dead as they were massaged into viable products.

The legendary product development focus of 3M is simple: Give people who want it some time to come up with something they could be passionate about. Then use the passion to do the hard work of birthing (or killing) a new product, with a little money to help.

Why not turn Silicon Valley inside out? Instead of leadership guilt about data bloat (there must be something we can do with the data), why not look away from the computer? Why not use IT to help deliver something that people really want? Lose the next computer toy and switch your lens to the people that you live with, work with, sell to, and buy from.

Salt and Straw is a fabulously successful chain of West Coast ice cream stores. They have married the product innovation of Ben & Jerry's with a happy environment of upbeat music full of smiling folks offering spoons of flavors you'd never try without a sample (coconut and bee pollen?). And yes, there's a people story behind each flavor: “Sebastian Cisneros began as a chocolatier but started sourcing and roasting beans from his native Ecuador to make his own flavors of chocolate. To honor his new Abeja bar, we make a bee pollen and baked milk custard ice cream ribboned with dark chocolate fudge.”4 The stores are places where people want to go, unlike the dreary, dirty, sterile chain stores that they compete with. The power in this innovation is in the happy people and the happy store. The rest is good but not remarkable. The innovation is that it's a happy place that happens to sell ice cream. The lines are out the door daily, even in winter. People will pay a lot to be instantly happy, especially if there's no hangover. That is the innovation—and you get ice cream.

Turn the usual new product process on its head. Ask people questions first:

- What would people love to change (start or stop)?

- What do people hate about their work, their product, their process?

- What do people like to do around here?

- What would customers dearly like to make disappear?

Refine these like gold: Cook ideas down until their people appeal is clear. (Of course, there are improvements that improve profit, but the ones that last are the ones that people learn to love.) The basic principle is to focus on the ideas, not on the process of evaluation, trial, adjustment, and so forth. Those are needed, but if the ideas are lousy, they don't matter. Further, if each good idea has a patron who will kill to make it successful, the test and growth periods are more likely to pay off.

Pick your wildly successful product idea: Facebook? Started by college guys who wanted a quick reference of girls in their school—a hormone-driven product that cost nothing but time on the computer. It got off the ground because of passionate sponsorship. Subsequent iterations had many drivers, but the power is in the original basic concept.

Let's make this even simpler. Sort your search for ideas driven by emotion. You know, love, hate, fear, aversion, embarrassment, frustration—you add to the list. In fact, go back to the numbered items on page 183. Read them quickly, and stop when one of them provokes an emotion in you.

Your personal refining process:

- What's that about, in you?

- Is it something that other people might click with?

- What would boost the power of its appeal?

Now invite other folks into the game—people who want to have fun with a new idea. Ask them to go through the same processes in the next twenty-four hours. That will provide a basket of ideas that might have some people power that's bigger than you imagine.

People who work with machines all day have all kinds of feelings about their machines and their workdays. When I worked in a trash hauling company, I was amazed to learn that drivers timed themselves all day, with critical time points on each route. The payoff was finishing early to go do something else they liked to do. When we proved that there was no safety or service risk (owner's concerns), drivers could go home when they were done, and in less than a month we revised their routes to be more efficient. That saved enough truck hours so that we could avoid buying another truck to service additional yard debris (mandated by the city). All were happy: owner, drivers, customers, city. In this case, the passion was avoiding fake work and getting some free time that they wanted.

What about opportunism? Opportunism is a suggestion box writ large—huge, in fact. By the way, if you're successful with a suggestion box for eighteen months or more, please call me immediately. I'd like to know how you did it because you'll be the first that I've met. A suggestion box is opportunism with nobody home, and there's no cheering squad to light up the person with the idea. It works at first, but then the combination of dreadful ideas and employee anger at rewards that are either insufficient or irrelevant pretty much grinds the program away. Just don't do it.

Instead, how about listening? Wait! Before you roll your eyes, try this: Schedule at least one hour a week to walk around and listen to a few folks. Ask the next question after they've answered your first one. The next question? Something like one of these:

- Why now?

- How is that different from what we're doing?

- I'm not sure I understand. Could you explain that a bit more?

These discussions will be idea starters for some improvements, or maybe door-busters, if you'll listen, probe, and act interested. It's really in there, but it needs to be coaxed out like coaxing a cat to a new dish of food (or a dog, if you're not a cat person. Neither am I.).

Here's a listening tip from one of the best: Oprah Winfrey. If she's become a billionaire by doing this, maybe she's worth a listen. In this scenario, she is listening to folks in a small group equally divided between Trump supporters and Trump non-supporters. Sitting next to a Trump supporter: “I could feel him tense up. I decided not to take on his tension, but to do the opposite, which was to lean in. . . . Every time I feel him bristle, I turn and say, ‘Tell me what you think, what do you say about that?’ That is how you hear people.”

“It's her superpower,” says Reese Witherspoon. “She really listens, and she is genuinely interested [emphasis added].”5

This is a top payoff to you, if you'll decide to master it. It's about attending to the other person, despite your own discomfort. Your challenge as a leader is to listen with genuine interest, in two areas at once: the people and the content of what they are saying. Most of us are trained to value the content first, and it shows. The problem is that your success depends on those people even more than on their ideas. If you doubt it, then you go do their job.