Chapter 10

Resilience

The beginning of wisdom is found in doubting. Pierre Abélard said, “By doubting we come to the question, and by seeking we may come upon the truth.”1

The dreadful appeal of change is that it lets us look away from today's challenges to wonder into the future. The power is with today's demands, but the intellectual promise is about tomorrow, compounded by relief from today's intransigent dilemmas. If the answer is balance, how do the best accomplish that?

EXPECTING THE UNEXPECTED

Organizational resilience is informed response to the present, with a bit of good guessing about the future. Its foundation is execution; its future exploits execution and doubt to find opportunity. A surprise is always unplanned. The better way to deal with it is to build into your organization the habits of responding to performance problems, with practiced escalation to strategy when needed. Then the approached is planned, even if the surprise is not.

The first answer, then, is to create brain space for the unexpected, whatever it might be. Drop the dream that there's a shortcut or that others can “see” the future better than you. They can't. Here's a rule that's so simple, but most folks won't do it: Devote at least an hour a day to reading, reflecting, or experimenting.

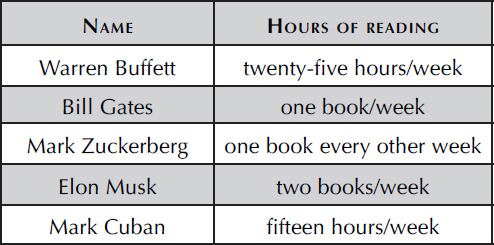

What does this look like? Here are the reading habits of famously successful folks:1

To “devote” means to give something the attention that you now award to the most precious thing or person in your life. It's on your calendar with “Do not disturb” all over it. If you struggle with this, your dilemma is plain: You're running on empty. Although it's a common problem, it won't get you where you want to go, so stop it. Do what successful people do to maintain their discipline: Fall in love with where you want to be so you can enjoy the ride. After all, this is feeding your life. If you have trouble feeding your life, that's a second flag that you need to get help—a coach, a therapist, or a wise advisor who will help you build the walls to keep out the evil diversions.

There is no “fast track” to reading. Just pick up a book or a magazine or a newspaper with substance and start reading. Write notes in the margin when an idea strikes you. Some folks find that a daily log of learnings (phrases) or a weekly note to your key folks about what struck you in the current reading will pull you into reading because you've made an implicit promise to produce something with it. Your product is an idea, not necessarily a plan. It's called learning for its own sake. John Wooden, arguably the best coach in basketball, says “People with initiative will act when action is needed.”3 Harness your initiative and fear of failure to read and learn and doubt. It will open doors that you can't imagine.

The second answer for the uncertain future is to implant a culture that masters goals, budget, KPIs, and initiatives (GBKI) so that it can build a series of processes for managing the unexpected through the review and adjust meeting (RAM). That framework is universal and will travel to whatever business you develop. Without it, operational interruptions will suffocate the understanding that success requires. The heart of GBKI is the review and adjustment of meetings and actions that follow it.

Bar-tailed godwits fly 7,000 miles in eight or nine days straight from Alaska to New Zealand for their summer. The real question is how they find their way, or how they adjust their path to stay headed at the target (RAM) because wind and weather likely push them off their planned daily path. The answer is an internal guidance system that uses Earth's magnetic field lines updated by positions of the sun, landmarks, and stars. That system combines magnetite (a mineral that acts like a magnet) in their bills with magnetosensitive eye molecules to sense the earth's magnetic field and then guide the birds back to the flight path.4 If birds have a system to get back on the path daily, why don't all businesses, including yours?

Resilience Cycle

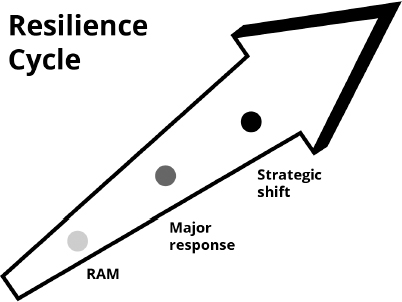

The review-and-adjust system does the same job for an organization that the godwit navigation system does for the birds’ migration: It's a powerful way to make course corrections in the moment. The RAM produces planned actions that may improve results. If not, a second window opens (major response), which suggests a deeper problem that may need more investment (people, time, machines, data) for a solution. When the deeper problem recurs, a third window opens on the need for a strategic revision. When to move up to the next window? When frequent diversion or escalating risk occur. Trend data matters here, requiring that a decision to act demands more than one data point (except in an emergency, of course).

Figure 10.2 below details the three stages driven by the RAM to get back on course: RAM, major response, strategic shift.

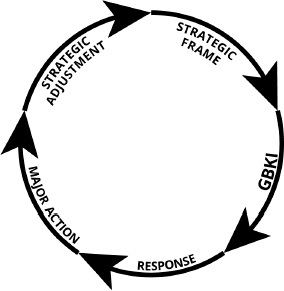

The resilience cycle, illustrated in Figure 10.3 on page 216, is built on faithful execution of GBKI. Without it, leaders are at the mercy of their emotions or history, both lousy guides to a successful next step.

A strategic frame (plan) outlines a narrow set of paths to success. Clear GBKI will point out good and bad results, rapidly teeing up the questions that need answers. Those questions lead to a RAM and subsequent actions. The task of leaders, especially at the top, is to assess whether the first actions from RAM are adequate. Frequently, either the problem or the solution will be new to the organization, which presents both opportunity for success now and a training exercise for unexpected problems in the future. All unanswered problems are unexpected, and solutions that work often require more than one try.

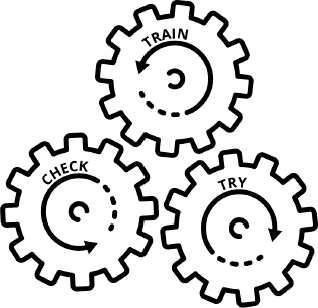

At Fort Dix, New Jersey, we taught new recruits how to use their gas masks. We walked to a small cement-block building, stopped, helped them prepare, and walked with them into (and then out of) the building, which contained a virulent blend of tear gas. Those with mask problems knew it immediately and scrambled out of the building nearly blind with tears. As soon as their vision cleared, they sat down to master wearing the mask before reentering the building. Everyone was required to master the mask, and nearly all did. The point is not that most mastered the task; it's the TCT process: try, check for proficiency, train, and repeat as needed (pictured in Figure 10.4 on page 219).

The number-one weakness in training (other than doing it) is in the checking. It's not that the checker knows how things should be done; it's how she or he checks that makes all the difference. The point of checking is to transfer knowledge to the trainee, not just to click the box on the checklist. If you find the air in a car tire is low, you've checked. Unless you refill the tire, you flunk.

It's what police and fire responders and surgeons do to master their craft and improve their performance. Don't miss the subtlety, though: They are rehearsing situations that are known possibilities but not yet encountered by them. That's not the same as situations that are new. “New” has a double meaning: I haven't experienced it, and neither has anyone in my organization, so we have limited data about it to help solve it. That multiplies the difficulty of mastery and raises the need for expert training.

This process seems obvious, but it is seldom practiced. A friend and emergency room physician moved after some years of medical practice to open one of the early brewpubs in Oakland, California. As he observed his top managers, he was floored: “As a physician I was taught: see it, do it, teach it. We weren't proficient until we'd demonstrated teaching proficiency in front of another physician. In business, there's little training, it's not very specific, and there's little observation of hands-on performance until there's a problem!”

THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN FEAR AND FORTUNE

The heavy breathing about courage ignores the reality that usually fear arrives before the courage, jamming our competence. Courage is doing what's needed despite fear. Instead of focusing on the fear to make it go away, the question is: How can one perform well while afraid?

A leader's main job is to make bets—on opportunities, people, machines, marketing campaigns, buildings, customers, and any three items that you can add to the list. Fear accompanies uncertainty when outcomes matter. Healthy people accept the real fear of disappointment and failure and learn to harness it toward the next success. Fear is a problem when it's the only tree in the forest, attracting compulsive circling to understand why you're afraid. “Why” is seldom helpful, and it perpetuates the myth that successful folks aren't ever afraid. The hundreds of top performers who are so afraid that they vomit before their performance include singers Adele and Beyoncé, soccer superstar Lionel Messi, and NBA legend Bill Russell.5 Instead of the promise that “real leaders” aren't afraid, how about close attention to the people who find a way to perform even though afraid?

One way to reduce the odds of weak responses by fearful leaders is to bring fear right to the front porch of the business. A new technique explained by veteran futurist Bob Johansen is to go ten years out to the future and look back.6 Forget about accurately forecasting ten years into the future or anything beyond twenty-four months. (Frankly, most forecasts beyond eighteen months make the forecasters feel good but are of little use.) The power in the ten-year look back is the set of answers to the real question: What should we be considering now, if this imagined future happens? The answers can be developed into an extension of the usual annual planning process, organized using these two steps.

Toolkit: Power Forecasting

Ask: Looking back from ten years into the future, what should we consider now?

Sort answers into two groups:

- Topics with clear processes known by others, but not us, that we need to learn.

- Topics that are new to us and most others, with unclear paths to manage them.

You've now built your roadmap into the new future.

Topics in the first group become potential action items to be prioritized with all others in the annual plan. Unless there is data marking it urgent, resist the urge to deeply and immediately jump into it. Instead, like most initiatives new to the organization, test a part of the response in a segment of the organization that will welcome the learning, be advocates for expanding it if justified, and will help teach it. If it seems urgent (significant progress needed this year), then move it to the top three business priorities, and act as you would with any top priority:

- Communicate its status and reason why to all employees.

- Expect supporting plans in each department to be presented to the management team.

- Review progress and method updates with the management team quarterly, on a schedule.

Topics in the second group are “new-new,” and call for this approach:

- Sort by expected birth date: Will we need to respond in less than twenty-four months or more?

- Sort by expected impact on the business, even though these are best guesses.

If it requires action before twenty-four months and his high impact, move it to the top priority list and let it compete for top three.

Unexpected events will occur, their timing is sometimes a surprise, and parsing them with best current knowledge may make better responses available in a timely way. Fortune is a state of mind, more than any product or optimizing technique. It is opportunity married to healthy return, spurning shortcuts. Shortcuts usually cut short both the time and duration of the benefit, so serious folks take them off the table.

Much is made of the lean manufacturing revolution's explosive impact on the Toyota Motor Corporation. For Toyota, lean is a way of seeing and then acting. Here are two examples that are fundamental to the Toyota approach:

- At hiring, every employee agrees to do the two required parts of their job daily:

- Do their daily work.

- Find ways to do that work better.

- Early training for potential managers and engineers includes “a day of seeing”:

- Stand for a full shift in a marked place in a factory, not moving except for meals.

- Note everything that happens.

- Prepare to discuss what you've seen with your trainer.

Beyond the obvious expansion of “seeing,” the investment of time and teaching communicates powerfully the value placed by the company in these skills. A corollary for leaders is that the most convincing way to teach priorities is an investment of time.

If that's Toyota's system for finding fortune, what's yours?

Toolkit: Results Multiplier

Here is a results multiplier to get you started. It peeks through a different window to highlight actions that will accelerate your results.

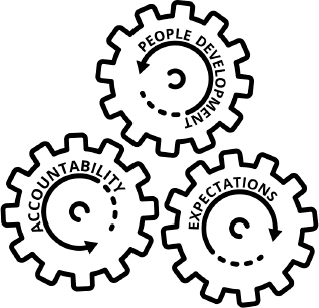

Expectations. Sloppy expectations are the root of friction between experienced employees and green folks. Experienced folks think that what's expected is obvious. New employees are often blind to the obvious for reasons beyond the control of experienced employees and managers. What to do? Spell out basic expectations, and check for them as a part of usual onboarding and accountability observations.

Accountability. Change your accountability expectation from catching mistakes to coaching excellence. The point of accountability checking is to clarify the next steps in performance improvement, and then assist in learning those new steps in the performance journey.

Expectation-driven people development. Expect managers to both deliver the numbers and to deliver teams and individuals that share these expectations for themselves:

- They know what they need to do daily.

- They ask for help to do it on time and properly.

- They feel safe in recruiting their curiosity to find newer, better, simpler ways.

- They think it's their job to find opportunities for themselves and for the company.

IF EVERYTHING ALWAYS WENT RIGHT, WHO WOULD NEED YOU?

The unsettling truth is that successful organizations make changes because that's where the value is, whether it's solving a problem or developing a product. That means moving away from the way things are now. It's unsettling to realize that “we can't stay here,” however, and it's made worse by our tendency to fear loss more than to desire gain.7 Mistakes or falling short are a normal part of every change, every learning process. No one gets all the math problems right the first time (in fact, they are designed that way). Falling short is universally unpleasant, even in the healthiest folks, and the ability to restore progress toward the goal is vital. Two books of extensive studies about success and failure offer helpful paths to the success journey:

- Grit by Angela Duckworth documents the consistent hard work that success demands, alongside inevitable boredom, pain, and confusion.

- Mindset by Carol S. Dweck, PhD, explains the difference in mindset between people who think they can learn to do better, and folks who think they are stuck with who they are today.

The core finding of both books is that focused effort beats talent. Yes, focused effort plus talent can equal greatness, but those are outliers. The first response to the feelings of disappointment, fear, confusion, and doubt that come with falling short is either to deny them or comfort them. Neither helps the people or solves the problem. Instead, there is a three-step approach, a problem reset that works for both optimists and pessimists: acknowledge, normalize, fix.

Toolkit: The Problem Reset

Here are the three steps to the problem reset:

Acknowledge the problem. Say out loud something like, “That didn't work.” A speech isn't necessary, but it is vital to say in front of the concerned folks that as a leader you see that there's a problem. Otherwise, the message for some is, “We don't talk about problems here.” In 2017, General Electric Corporation uncovered system-wide problems that caused a precipitous drop in their stock price, a substantial board reorganization, major restructuring of the company, and more. The criticism was that top leaders didn't want to know about problems, and discouraged discussion of them. That's the opposite of what works. Problems mentioned usually can be evaluated and either resolved or dropped. Problems hidden will prompt a virus of other problems as they multiply in the darkness.

Normalize the problem. Remind your people that all change produces problems. There will be problems when the computer system goes down, when groups miss a key action, when the team is not prepared, and so on. Remind your team that problems can be fixed, that they have been fixed in the past, and they can be fixed this time too. This perspective balances acknowledgement of the shortcoming with a perspective of the future that is positive. It is sufficient for all but major catastrophe.

Fix it. Take a small step to begin to solve the problem or reduce the damage. Big problems can destabilize people, which dilutes their ability to think or act. Initiating small steps immediately will dilute the fear, reinforce feelings of competence, and usually, will open the door to more comprehensive solutions. This feels counterintuitive because the big problem still looms, but unless there's an immediate solution that will completely restore order, the small-step approach will recruit the best skills and instincts of your people. At the same time, start the search for a permanent fix. Keep moving forward on both.

The best leaders balance the need for change with the need for predictability. “Need” is the right word. A significant fraction of folks mostly prefer consistency in their workplace and work assignments. And they often are the solid B players who are the foundation of a successful organization. They embrace change if it's presented clearly, well in advance, with modest and specific goals and expectations that they think they can either meet or learn. Their strengths are the cash generators and the launch point for successful growth. They include deep organizational knowledge, pride in doing good work, understanding of how to get things done, skills in their tasks and essential adjacencies (sometimes disparaged as tribal knowledge). Their appetite for change requires seasoning with preparation, training, personal relevance, and frank pictures of why the change is essential.

Media's thirst for drama feeds our fetish with unproven startups (AI, virtual reality), most of which will fail (“fail fast”). Valid in the search for dramatically new businesses, their example of unhinged change is a poor matrix for successful growth. The undramatic truth is that most successful firms grow modestly but relentlessly. Real business power is fueled by relentless performance because customer re-purchase (the prime metric of successful growth) is about customer satisfaction, not the whiz-bang of the technology.

The formula for successful change leadership looks like this:

- Institutionalize the search for change.

- Expect results.

- Create solid linkage with existing people and processes.

- Maintain consistent recognition and stimulation of existing practices and people.

Today's examples of this formula include both Facebook and 3M, even though they are radically different from each other.

THE FUTURE IS NOW

Robert MacLellan, cofounder of the remarkably successful Pacific Coast Restaurant chain, explains how it all started: After a Navy career as a petty officer, where he learned how effective training and disciplined execution live together, he and his three partners were invited to open a Wendy's franchise in Medford, Oregon. They did so with a bang: Sales and profit grew to triple the national average for the chain! Wendy's founder, Dave Thomas, flew to Medford from Ohio in his company plane to see it. Although built upon many details, including extreme care in hiring, these principles stand out:

Close control of costs. The high volume and low margins in the fast food business demand exemplary cost control, especially in food cost and labor. Relentless focus on both became a foundation of their business. According to Robert McLellan, “You drop a little cheese on the floor, there goes your profit.”

Collapse slow points (CSP). In one year, they reduced the time for a customer to get a hamburger from the company standard sixty seconds down to thirteen seconds. Each. For an entire meal shift, lunch or dinner. How? By identifying slow points in the process, looking closely at ways to reduce their times, and teaching their people how to do it. Not only were there lines out to the street (partly because people wanted to experience it), but the cars never stopped rolling! Servers with headsets walked up the line taking orders and sending them to the kitchen.8

Surprise customers with powerful value. The point of the speed and cost control was a quicker good lunch. Customers liked it so well they lined up for it. That's value.

What does this have to do with the idea that the future is now? Robert's team didn't wait for the future to come to them. They understood that there is no such thing as the future. There is only now. The future is an accounting device that totals up the nows. A bit of Janus, the Roman god of transitions whose two faces looked forward to the future and back to the past, applies here: Look to the future to inform actions now, when it matters. What future can your now provide?

Before you object that your business is different from Wendy's (of course it is), ask yourself: Would you like to triple your profit? That's what Robert's team did in a year in Medford. Your results may vary, but the odds are with you if you'll try this tool.

Emphasize the total result, not any one process. Whenever you make a process change, check the impact on your customer, not just the change at the slow point. If the change is invisible at the shipping dock or the delivery point, move to another slow point. High-leverage improvements like cost control or CSP can crush your competition with superior offerings in quality, packaging, personal service, or even price. The idea is to invest the savings into two pockets: profit and customer value. Done right, it's included in the training and accountability systems that already exist. In fact, price may be the last thing that you change, unless you move it up.

Too often, attempts at cost control and faster delivery descend into cost cutting (quality cutting) tacked on to a work speed-up. Both are the wrong approach. Unless an improved process enables faster throughput, speed boosts waste and the chance for injury and quality busts; speed becomes the enemy. Instead, step up to the courage plate and ask your team to collapse slow points anywhere in your entire process, from order to delivery.

Toolkit: Collapse Slow Points (CSP)

- Recruit your best slow-point collapsers to teach others what to look for.

- Ask them to pick a slow point.

- Arm them with a few good questions to speed the search.

- Spell out the collapse point and the fix.

- Build in training for the new methods so your people can do them easily.

- Track and proclaim the results weekly, preferably to all in the company.

- Ask the final question: How can we translate this into better customer experience?

For Wendy's in Medford, the improved experience was service so fast that folks came to see it and stayed to buy. The power in CSP is to increase both profit and value for the customer, chosen so that it matters to the customer.

“Now” Is a Business Stance

The power of now isn't speed; it's offerings that click neatly into customers’ wants, even before they know they want it. Speed is not enough. What wins is best summarized as value: something customers will pay for, delivered quickly.

Menswear retailer Bonobos is successful not because they're on the web or because of their prices; they are not cheap. They win because they solve these problems:

- Men (like me) hate to shop.

- Men hate their pants. (According to research done by founder Brian Spaly with business school classmates and others.)

The Bonobos formula offers pants and clothes that fit, good selection, quick shopping, and prepaid returns. GuideShops offer a brick-and-and mortar place for a customer to reserve a time with an expert who will help find clothes that the customer prefers, see that they fit, and ship them to the customer at home. The clincher is its insistence that their customer service “ninjas” be human with their customers, treat them like people, think what they would want if they were in the customer's shoes, and then do that without fear of recrimination. It's the Nordstrom formula strapped to Internet speed.9

PERSONAL RESILIENCE

Self-care for leaders is vital. Always. The memory of an all-nighter is destructive because it promotes work that's late and lousy. If I imagine an all-nighter to resolve today's problems, my fantasy will prevent pruning priorities to the success core. The payoff for self-care is that you're present enough in your now to have a chance at success. Here are your first four examples of self-care:

Humble leadership. Leaders still lead, but with humility that owns the real possibility that they might be wrong and that they will learn from others. They don't need to be right all the time, and they'll do better if they aren't. Humble leadership doesn't dilute the urgency to act. Instead, this state of mind creates space for reality to emerge and encourages others to step up and into it. Instead of rejecting an idea that seems wrong, ask, “Why do you think that?”

Deep personal relationships. “Loneliness kills,” according to Harvard psychiatrist Robert Waldinger, current head of the Harvard Study of Adult Development, a one-of-a-kind eighty-year continuing study of physical and mental health of more than 2,000 men. People who have one or two close personal relationships for much of their lives will do better by virtually all measures than those who don't. These relationships can be marriage, friendships, at work, outside work, or beyond work. Let them grow deep over time. How to do it? If you have it, keep it. If you don't, start looking for folks that you enjoy and that wear well over time. Regularly spend some time with them. (For more on this topic, find Dr. Waldinger's TED Talk, “What Makes a Good Life? Lessons from the Longest Study on Happiness.”)

Hope. A hopeful life stance isn't Pollyanna weakness. It fuels the vitality that draws organizations and people into their next challenge with a growing chance of success. Says psychologist Martin Seligman, PhD, “Believing that you have some control over what happens fuels trying. If there's a potentially good event for me, I'm going to seize the opportunity and follow up.”10 Hope doesn't always have to be successful, but it increases the odds of success.

Persistence. This is especially important when trying new ways to get to your answer. Caltech physicist Leonard Mlodinow says, “You have to keep trying and accepting failure, because the more at-bats you have, the more likely you are to get a hit.”11 Persistence has been glorified in every success story, regardless of where it happened. Why not grab it for yourself? How many successful people have bragged about how little persistence their success required? Even notorious bank robber Al Capone robbed multiple banks. Why do you think the world will treat you differently?

The secret of a resilient organization, then, is practice in spotting problems and opportunities, and jumping on the ones that matter in the present. That capability becomes resilience when surprises show up, and they will. The secret of personal resilience is a solid mix of hope, a few close relationships, humble willingness to seize failure as painful opportunity, and dogged persistence. And the greatest of these is persistence. All four are available at your door, now.