Chapter 7

No One Believes What They Read or Hear

Leadership is not about communication. It's about meticulous listening at surge speed, linking closely with each person as they talk or write. “I feel you,” a rap cliché, is code for “I understand at a deep emotional level.” That personal link is a connection that's heart to heart, not just head to head (although that's where it may start). It may be the best description of a super leader.

YOU ARE THE AVATAR

An “avatar” is an exemplar, a symbol that can be a living person. Avatars typically absorb an image that is created by the beliefs of the person who observes it. To make it simple, as a leader you are an example, a living metaphor, and become whatever your employees believe about you. Strangely, their beliefs have more power over their performance than who you really are, unless you let them repeatedly see the real you.

This is bound to collide with your public face, which is a cover for the humanness that you reserve for your kids or your dying sister or your mom. But aren't you the same person at work, at home, and in the hospital? Where is it written that you must change into a different person at work?

So there's proof that you can do this. If you've done it at home or in the hospital or on the field coaching your kids, you can do it again. It's now in the realm of “want to,” which you control, pretty much. So much for claiming that this doesn't apply to you.

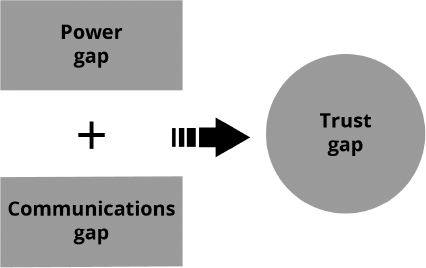

Research shows that 82 percent of people don't trust the boss to tell the truth.1 The source, Edelman's Trust Barometer for 2013, reports results from 31,000 respondents in twenty-six markets worldwide. After you convince yourself that your own statistics aren't so damaging, just get to the point: There's a trust gap whenever there's a power gap, especially if it's topped with a communication gap. You can do some things to reduce the gap, and reduction is better of course.

We'll insert the mandatory note about discipline to observe that discipline works just fine in a high-connection/high-trust environment. North Carolina and former University of Kansas basketball coach Roy Williams, responsible for years of top-ten teams, routinely has the team to his home for Thanksgiving dinner. Somehow, he's secure in his position as head coach and head disciplinarian. It has worked for years.

In a survey of 1,000 American executives, psychologist Michelle McQuaid found that 65 percent of executives would trade a pay raise for a better boss.2 But wait, there's more. Fred Rogers hosted Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood, an iconic children's TV show, for three decades, and won three Emmys and more. If you were a kid or a parent from 1968 to 2000, you likely saw him on TV, softly powerful. Tom Junod in Esquire magazine recounted what happened when Fred Rogers accepted his Lifetime Achievement Award in front of the usual crowd gathered for the Emmy Awards: He bowed and said, “All of us have special ones who have loved us into being. Would you just take, along with me, ten seconds to think of the people who have helped you become who you are? . . . I'll watch the time.” The crowd swallowed their laughter and then understood that Mister Rogers was serious and expected their cooperation. As Junod says, “People realized . . . that Mister Rogers was not some convenient eunuch but rather a man, an authority figure who actually expected them to do what he asked.”3

Remember empathy, one of the five essential leadership skills per the US Army Field Manual? You saw it there, and nobody expects you to be Mr. Rogers.

Reducing the Power Gap

So now you're busted. You have it inside you. The question is: Do you have the guts to let it out? But first, let's talk to the voice in your head that says something like, “That's for other people who don't have my job or my people.” Sadly, it's true as long as you want it to be true. If you're still wriggling away, reread what you just read. If you want to get better, here's a starter: Imagine that you could feed magic food to your employees that would light them up, bring them up, enable them to deliver all that's in them. Yes, you can. No, it doesn't work all the time, but it works often enough to make a difference. The doorway to change is reducing the power gap and the communications gap between you the leader and your people.

Here are five steps you can take to reduce the power gap in your organization.

Get over your title. It's an invitation to contribute, not a statement of rank. Colin Powell, one of the highest-ranking generals in the United States, said, “The day soldiers stop bringing you their problems is the day you have stopped leading them. They have either lost confidence that you can help them or concluded that you do not care. Either case is a failure of leadership.”4 If you imagine yourself as helper instead of leader, you're off to a good start.

Don't lean on your ability to fire people. That ability looms in the background of all employees, but it is of tiny consequence to the business. It is not an element of leadership; it's emotional blackmail. If you rely on it, you'll get the response of people who feel blackmailed—all defense and no initiative. Usually, if you must fire a person, it's your failure for hiring them or not training them. Occasionally, folks self-select out, but not often.

Apply railroad leadership. When you walk around, stop, look, and listen (especially listen). You don't have to produce brilliant anything, other than thanks.

When you walk, ask one question at a time, and aim it at just one person. An example might be “What's hard right now?” Listen closely, look closely, decide to be interested, and ask one or two more questions to paint the picture a bit better for you. Your task is to understand something you didn't understand before. It's not to fix anything. If you hear a problem that a supervisor needs to know about, ask if the supervisor has been alerted.

If the answer is no, that's data for you about communication in that team. Store your information for future discussions. It may become part of the fabric of a complex situation that helps find the thread to unravel it.

Apply these techniques in meetings. Especially in meetings, be present to each person as she speaks. That means no phones, no computer, no interruptions from outside the meeting (people, messages, phones, texts—you get the idea). Most vital, bring your brain to the room. Work on other tasks later. People can tell if you're with them. Always. Why would they commit to you when you're only half committed to them?

Note: These aren't groundbreaking ideas unless you're not doing them regularly. Doing them is groundbreaking!

Reducing the Communications Gap

We'll reverse it and give you a place to frame your gap-shrinkers. Here are the steps:

- Picture three of your most vital leaders.

- Write down one thing you'll do with them. It may be spending fifteen minutes with them, or going for a walk with them, or sitting down with them in their cubes and asking what you can help with (or bringing a topic that you know they are struggling with). Mostly, listen and ask questions.

- Do it. The point is not to challenge them to produce an answer, it's to introduce them to a new way to use you—as a helper, sounding board, and committed partner. It's your task to pull them into the conversation, so go gently into it.

Note: There is nothing here about solving the problem. Nothing. Let the gap shrink. It will.

CONTENT AND PROCESS: THE TWO ASPECTS OF COMM UNICATION

The test of communication is only “What did the audience hear?” I use “hear” as a broad label for the brain action that processes inputs from all senses into pictures or memories or ideas in the brain. These ideas are what we respond to and what we remember. My memory of a blue rock is different from everyone's memory, even though the rock is the same for everyone.

My dad, who finished his high school education in a tiny Oklahoma town, said that if someone can't read your writing, you might as well not write it. My piano teacher tirelessly reminded us that music was a form of communication. With yourself or others, no communication = no music.

The Content Challenge

The problem with content isn't the audience, it's the writer. Content unlearned is wasted, regardless of the setting. If Einstein hadn't communicated E=mc2, it would be the same as if he had never discovered it. The challenge for most of us is that we work at content, but shoot from the hip regarding communication. The evidence? When you hear a powerful speaker, it's his presentation as much as his content that grabs. And what is it about the presentation? You are pulled into his ideas. Yes, content is vital. The great speaker without content is boring. There, I said it. Now, about your content . . .

The three rules of content:

Rule 1: It's for other people, not you. Test every core idea on someone else. A core idea is the heart of your message. Find people who don't worship you but share your commitment and understanding of the situation. Push past your reluctance to be called out as missing the target. See if they effortlessly get it. Probe to discover which part they missed or found pointless or boring (or however it misses the mark). Ask why. Use their ideas to sharpen your content.

Rule 2: Present the truth, period. This is career threatening. There are “stretchers,” and there are “diggers.” Stretchers embellish and exaggerate a bit. Diggers present a wearying fabric of evidence that can't be grasped without outrageous work. If you feel very smart after crafting content for a presentation, check it out with someone. Your power is in the simple light you wield, not the complexity of your story. You're not writing a high school essay here. Neither stretcher nor digger is a compelling storyteller because their content is either suspect or impenetrable. Telling the truth simply is a rare gift. It will distinguish your content. Ask yourself, “What is the most powerful truth in my message?” In this instance, “powerful” translates to impact on essential results.

Rule 3: Make it simple. Most powerful ideas are simple. It's when people try to power them up by adding capes and jet belts that the light gets blocked. Start by writing down the takeaway: What single idea do you want your audience to take with them? It doesn't matter whether you've heard this before. If you don't do it every time as a separate step, your communication will be weak. If you have more than three takeaways, you've lost your audience. They'll choose to retain what interested them, which might be a random thought entirely outside the discussion. Watch their eyes: Do they get it?

The Process Challenge

Communicating is a skill and an art. If you think you're so good that you don't need the tools of great presenters, I dread your presentations. Great communicators work at communication as much as content. Every time.

Joth Ricci, a successful serial CEO, talked about “distraction management” when I spoke with him.5 He's referring to keeping the organization on track toward its goals, instead of wandering after the next appealing thing. Apply this in your presentation. Look for the through line, the logical sequence of ideas and illustrations that stay on point. Examples and pictures each must serve the main message. Intriguing stories that stray are left out. Always. The search for entertainment can misguide even the best of us. The best of us don't succumb. Tell the entertaining story some other time.

Apply these rules of presentation:

Rule 1: Make it simple. Wait, didn't I just say that? Yes, but make your presentation simple too. Use the smallest word, the simplest example, the shortest story that will make your point. You want your audience to experience communicating with you like an amusement park ride: Clear entry, simple story, a bit of tension, a quick conclusion, and immediate exit.6

Rule 2: Paint a picture. Build a metaphor or a diagram for the key point. A metaphor says, “It was like a [fill in the blank]” For instance: “The warehouse should look like a library: everything effortlessly in its place but easy to find.” Where possible, draw your diagram by hand. It will keep you from the complexity that will put your audience to sleep. The three basic diagrams compare two things (A versus B, two-axis graph); three things (Venn diagram); or two things in two situations (double-axis chart). I am not drawn to diagrams, but I do them because others find them helpful.

Rule 3: Use a simple structure.

- Introduction: Why this topic now? Why does it matter?

- Three main points: State each in ten words or less.

- Picture: One diagram or example for each.

- Story: Tell a story that brings the diagram to life.

- Ask three questions about the story/diagram.

- Action statement: Here's what needs to happen next.

Close with a clear next step. To get there, you may need to slow down, clear up misunderstanding and fear with more questions, and invite next steps, in that order.

Here's an example: Check the audience. Do they look dazed or ready to act? If dazed, say something like: “It looks like there's something else there.” Wait sixty seconds. If it's time for actions, ask, “What should we do next?” In either case, listen and ask questions to understand. In both cases your questions are to bring the group to the same place if possible.

Just because you think you're clear about what's next doesn't mean that you're right or that your team understands clearly. Your process is to address both possible roadblocks to progress.

REWARD BEHAVIORS, NOT VICTORIES

Mastery is its own reward. It's a drug with infinite potential to continue to grow. It steps in front of winning and praise as a key driver of personal success. Folks who say winning is the only thing (some famous speakers) know that winners win because they obsess about mastery. The secret about mastery is that it's available every day, not just on game day. Doubt it? Reverse your picture and imagine winning without mastery. It's like ice cream (which I love): the pleasure peaks and then is gone.

Mastery is the slow drip that pulls us to do better than we imagined. Better yet, it's personal. Mastery doesn't require that you're better than everyone. Instead, it's a feeling of a small success, one after another. Mastery is built on a series of small successes, each one delivering the surge to the next one. One of the appeals of video games or card games is the combination of mastering a session or a hand and winning a game. The successive levels for video games are successive chances for mastery. The power of mastering the level is way past the power of mastering the whole video game.

Life is like that. Leadership could be like that. It's the task of the leader (teacher, coach) to break down the target into bites that lead to success. Those bites are opportunities to taste mastery, a little at a time. Mastery happens a little at a time, but pride and personal power surge forth at each step. It's that pride and personal power that fuel the hourly successes that your business and life are built on.

If you'll notice, you're surrounded with bite-size chances at mastery:

- Classes for an hour a day, every day.

- Hit 100 baseline shots.

- Shoot one clay pigeon at a time.

- Did we hit this hour's production target?

- Go one month without an accident by going accident-free today.

- Eat three meals a day.

- Do a math problem one step at a time.

- Practice four measures of the song until you play them exactly.

What if a company value was “To provide daily opportunities for mastery”?

Now compare what you already know about the power of the mastery experience to what you do as a leader—or worse, the structures that your company provides to enable mastery experience.

An intermission here, to clarify the value “To provide daily opportunities for mastery.” If your reaction is that it's the employee's job instead of the company's job, I'd guess that your organization is a sitting duck for a competitor who consistently masters individual mastery. Yes, your customer offering, internal efficiencies, sales, and so forth must also be competitive.

Maybe it's time for a self-check. If things are working well, and you find yourself in the dual position of being the expense protector and the initiator, your leadership needs an outside examination. “Expense protector” means that your default on any new idea is no, unless outside evidence offers a compelling return. This stance kills chances for your people to enjoy individual mastery because they depend on your ideas and your agreement for it. They've learned not to suggest change that might need more thought or testing because you're a deflator instead of a mastery maker.

You might try this response to ideas that you aren't sure about:

- What's your evidence that it will work as you say?

- How would you assemble that evidence?

- Let me help you see where that evidence might be.

You've shifted the conversation from deflator to chance for a little mastery: learning how to gather and evaluate evidence. Imagine the power of a team with that skill!

If you're the primary initiator, it's because you've trained your people to let you do it. Worse, you're likely doing well enough that the dragon of entropy is slipping into your organization, invisible so far. Entropy is the natural slowing of everything when there is no new energy to spin it back up.

The fastest way to strangle entropy is to tee up bits of potential mastery for everyone. They'll be so busy going for each little bit that things will improve, even though many ideas won't make it to execution. Just look in the mirror and accept the idling power of your people. That low buzz you hear is their engines waiting to be turned up. Mastery will do it ahead of any system of pay, bonus, or commission.

The Mastery Formula

The idling power of your people is missing unless you pull it in. In the absence of chances for personal mastery, most of your employees do their job to avoid criticism. You can check this too with a survey that asks each employee: “How do you know if you're doing a good job?”

Go ahead and try it. Make it convincingly confidential. Don't bury it in a longer list of questions; don't do it in public; don't include it in the annual review. Those all have baggage that will prevent either individual contemplation or honest answers. Just ask the one question and leave space for folks to write as much or as little as they want. Suggest that they ask their spouse or partner to help. Give them forty-eight hours to respond. If it's less, they may be unable to fit it in, delivering a pro forma answer that's biased by what they think you want to hear. If it's more, they won't see it as important, and many won't do it. See that someone chases down every employee, even part-timers. Every employee matters because you'll use this data in these ways:

- To challenge your leadership team to rethink feedback and working with their people.

- To revise your metrics and how they're explained and communicated.

- To focus your executives on developing a culture that at least delivers these results:

- Every employee knows how she's doing at least every month, if not daily.

- Every leader has a simple system to report and record their people's performance.

- Metrics provide real data that pretty much everyone agrees upon.

- A burgeoning sense of priority about what folks work on.

- Define your own result.

The data on the power of mastery makes actual leadership practice worth challenging because it's often off course. Sloppy or nonexistent performance evaluations, poor job design, few chances to share mastery . . . the list goes on.

There's another reason that parents insist, when talking to their kids about their sports games, that they just have a good time out there. Skip the part about “kids these days,” prizes for all, and so forth. That's just so last century. No, the path to winning runs through a love of the game. It's that love that pulls us to try again. Yes, the hope of winning is fuel, but most of the life of an athlete is about practice, not the game. My grandson plays the trumpet. He's fourteen right now. He also plays whatever sport is in season, and more. Yes, there's a bit of drive to win a game or a prize, but every music lesson, every concert is a chance for a bit of the mastery reward. And in music as in sports, mastery is apparent through practice more than in a concert or a game.

What about victories? Aren't they important? Please tell me that your answer will be “Yes! They are chances for mastery!” It's just that there are so few games, so few annual reports, so few concerts, so few signed major customer contracts. Why not enjoy mastery every day?

MONEY IS NEVER A MOTIVATOR

The most ubiquitous data on leadership or management is that money is not a motivator, provided that basic compensation meets basic employee needs. And yet, leader after leader insists on reviewing their compensation program. I propose that pay structures are revised frequently because if feels like doing something for morale, motivation, performance, retention, employee satisfaction, and so forth. Take your pick. It's a way to avoid the tougher but more powerful ways to ignite excitement and motivation, as well as complaints about just about everything from leadership to the quality of the Internet.

Simplify the discussion. There are two kinds of pay: salary (with a bonus, if results enable it) or commission. There are two kinds of people: salary and commission. Match salary people with your salary plan and commission people with your commission plan. Check your rates in a well-regarded compensation survey; you'll have to pay for it or pay your HR firm to use theirs. Use a survey with job descriptions close enough to yours to show your people, and that matches your company size and geographic location. Adjust the amounts to the survey that fits you. Decide whether you want to pay your people in the top 10 percent, the top 25 percent, or the top 50 percent as a matter of policy.

Once you've matched your people to their pay pile (salary or commission), consider some details for special cases: super performers, high-potential new hires, and so on. Skip the drama about setting a precedent. Do the right thing, and be prepared to defend it to your board and your most cantankerous star employee.

Stop here: Money is still not a motivator, except for a few folks who prefer the risk of commission and who directly bring business to your company. Assistants, inhouse salespeople, technicians, sales engineers, and all the hangers-on who want to get the commission without the risk do not get commission. Period. If they want it, let them earn their way to a position that pays a commission.

Do not give or sell minority shares of ownership in a privately held business. Pay performance bonuses instead. Minority ownership shares are deceptive on their face. Except for some form of annual profit-sharing, they are unlikely to deliver their value to an individual unless the company is sold. That contingency can be spelled out in a simple contract specifying either the dollar amount or percentage of sale proceeds that they will receive. Ownership should remain in the hands of owners, and the fewer the better. If ownership shares have enough value to be meaningful, most firms won't have the cash to pay them out except when the company is sold. A few folks mistake minority shares with something of value. They aren't.

Bonuses are best paid from an annual profit-sharing pot, limited by minimum earnings at the bottom and cash required for prudent operations at the top. Beyond that, pay it out. The simplest formula is to pay each person a percentage of the bonus pot that matches their salary/commission's share of total salary/commission. To earn more, they help the company earn more. Discretionary bonuses may also be paid, but out of the bonus pot if possible, to remain financially conservative. I recommend paying sales commission outside the bonus pot and consider them in cost of sales. Discretionary bonuses above commissions should also come out of the bonus pot.

There is a myth that departments or divisions should be paid based on their performance. If they depend on other parts of the company for sales, supply chain, finance, and so forth, their bonus should be inside the pot. They could not make the sale or deliver the product without others, and the distinction doesn't hold up under scrutiny.

Here's another pay secret: You can't give raises big enough to motivate with money. Think about it. Whether an employee salary is $150,000 a year or $300,000 a year, they likely are living close to their salary. A raise of 10 percent, toward the top of the range, in either case is nice but not revolutionary. The $150,000 employee gains an additional $15,000 before tax, or about $10,000 after tax. That's a down payment on the lease of a nice car, but not a home (even a vacation home). Even when you double it, the dilemma remains that it becomes supplementary salary, not breakthrough money. Breakthrough money is a fifty-foot sailboat, full college tuition for four years, a million-dollar house—add your example. Even worse, in most organizations there is an attempt at salary parity, which enables comparison of pay across the company to align somewhat with value delivered to the company. That usually produces pay ranges for positions, and raises are constrained by the pay schedule. The effect of that is to hold back part of a potential raise for the next raise period so there's room in the schedule for another raise. Translation: Pay itself is more about recognition than performance, especially on the upside. Poor performance can produce pay cuts, understandable to most folks. But great performance can produce modest raises, a “good” bonus within the bonus pool, and the possibility of promotion (mostly just recognition because, with a few exceptions at the very top of the company, the extra money won't cause an explosion).

Whew! Lots of baggage about pay and compensation. The real motivators? Here's a basic list that goes a long way toward the autonomy that most folks prefer, built upon a company norm that promotes maximum autonomy within required coordination:

- A boss who listens and is fair, respectful, and demanding (perfection not needed).

- A boss who is long on questions and short on orders.

- A job that provides the right mix of challenge and predictability (adapt the people to the job).

- A job frame that builds the fences that define the minimums and possibilities, such as:

- Goals for the smallest organizational units possible, in the shortest blocks of time.

- Up to four simple metrics to track performance daily and weekly.

- Annual performance goals across the company measured quarterly and annually.

- Frequent feedback (daily, if possible) about what's good and what needs to improve.

- Leaders who use the frame to provide frequent doses of encouragement and coaching.

- Leaders who see their jobs as mostly knocking down obstacles, cheering success, and salving the wounds of falling short.

- Leaders who involve their leaders in annual plans, goals, and measures by setting two levels:

- Total company: Planners include department leaders and high-potential junior folks.

- Each department or division: No more than three goals per department to enable intense focus, but goals aligned with company goals so all are pulling in the same direction.

- Special “skunk works” projects to exploit a major opportunity that current operations won't handle well.

This frame is like a baseball diamond. Once you know the rules of the game, it's easy for folks to play their position and enjoy it—and it's the enjoyment that pumps out the bursts of enthusiasm. Your question as a leader: How often do your people do each of these?