Chapter 1

The Myths that Ruin Our Businesses

The four Kerry Blue Terriers looked identical. All were out for a walk in an open field with their owner. Three of the dogs bounded joyously about, reveling in the moment. The fourth ran in circles, relentlessly. Why? The owner explained that when he acquired the fourth dog, it had been living in a cage. For years, its exercise was running in a circle limited by the cage.1 The cage was long gone, but the dog remained inside it, at least in its mind. That invisible, powerful story guided the dog's perception of reality, and its life. Myth, indeed!

As a leader, how do you change the behavior of the fourth dog on your team?

We are pattern-seekers from birth, making sense of our environment. Doubt it? Videos of days-old babies show pattern-seeking. Crying begins as a hunger reflex, but toddlers shift to crying on demand, having learned that crying produces food, cuddles, attention. Our brains sort billions of stimuli from outside, ignoring most and processing few. More important, what do we do with the things we sort? They become our personal myths!

What is the link from patterns to myths? When we take in a bit of data, we apply our own meaning based on our experience, genetic heritage, and what we learn from reading and other things. Our meanings become our myths.

Now, wait a minute. It doesn't really matter whether our myths are true or not. Truth is not the test, because “truth” is “out there.” I see the sun moving from east to west every day, and in spite of knowing that our Earth moves, not the sun, I think (and feel) that the sun moves. Remarkably, that bit of error is a useful myth; it guides everything from which sides of the house require window shades to when we decide to put on sunscreen.

Myths are the guardrails on the paths of our lives. We put them there, often not realizing that we're letting them guide us. We all have myths that help us manage the peril and possibilities of the future.

Starting when I was ten years old, we spent our summers at a cabin in the woods in the Columbia River Gorge in Washington State. The woods were full of plants, bushes, bugs, frogs, and even bears (we found a bear print once and made a plaster of Paris casting of it for proof). We connected with other folks by boat or trail, usually trail, because our parents had first call on the boat. We ran the trail over and over every day, meeting our friends to play Kick the Can, go to the swim dock, play Hide and Seek, and other essential kid stuff. Finally, we found that we could walk the trail at night without a flashlight: signal achievement! We did it by feeling the trail with our feet because it was pitch black outside.

Here's how our myth was built:

- Walk the trail hundreds of times.

- Notice that we could feel the little holes, dips, roots, and rocks with our feet.

- Try it in the dark with a flashlight.

- Turn off the light and try it for a bit.

- Eureka! We “saw” without a light.

Where's the myth? The belief that we could “see” the trail and find our way home in the darkest dark. We did find our way home (it worked), but we didn't “see” at all.

By now you're starting to see that you carry hundreds of myths with you through your life, adding and dropping them as your experience grows. Experience in our context includes both physical experience and mental experience, because both impact our myths and choices. Your memory of Nelson Mandela from a movie can generate strong feelings much later, perhaps while viewing news of a public riot in the United States. Your memory is a myth built by your mind as you experienced the story of Mandela—despite never meeting him in person.

- Powerful emotions are linked to them.

- We have a sense of control as we deal with frightening life setbacks.

- They are affirmations of important values in a struggle about what is right to do.

- They offer protection from confusion and dread as we look into an unclear future.

- They offer encouragement to try something new.

We believe in myths because we need them to live our lives. Let's just use the results of intensive brain and behavior study, especially the past fifty years, and call our perceptions “myths.” These myths, and many like them, lubricate the gears of our life and are reinforced frequently, making them seem even truer. If you begin to observe your perceptions, you'll see the web that allows you to move through your life mostly efficiently: the connective tissue between your brain and the world. Otherwise, you'd get bogged down when you reach for the water faucet.

In our brains, the more a connection between synapses is used, the more we think it's true. “Knowledge” is synaptic connection in our heads. Sometimes it's scientifically verified by outside data, but other times, it's verified by our feelings.

Sisyphus, Greek king of Corinth (known then as Ephyra), was self-serving, crafty, and deceitful. Zeus, king of the gods, punished him by forcing him to roll a huge boulder to the top of a long hill. Exhausted, he watched helplessly as the boulder rolled back down the hill to the bottom, forcing a do-over. He could never quite make it to the top. Today, we refer to long, arduous tasks (like owning a midsize business) that seem never-ending as “Sisyphean” tasks.

The myth has lived on for thousands of years because it's a fitting metaphor for a common life experience. If you're the one doing the endless tough work, it can feel so familiar that it seems true. And for you, it is, conjuring up a picture about your life that's rich in detail and feelings.

Myths are superb tools to communicate complex ideas with others who know the myth. A myth is a metaphor on steroids, boosted because it describes an experience and the feelings that go with it.

MOST COMMON AND DANGEROUS MYTHS

The people in your organization, the folks that you rely on to make things work, are as full of myths as you are. And some of their myths are different from yours. And they aren't telling you any more about their myths than you tell them about your myths. And, in fact, most of their actions are driven by those invisible myths. This means that your leadership is mostly about guiding their myths and helping to create new myths in the process. The challenge, however, is that they—and you—carry myths that are both untrue and dangerous to your organization. Even more dangerous, they are seldom mentioned, let alone discussed or tested.

Here are some commonly held and dangerous myths. Each is wrong, and hazardous to your health and your business. Which of these are familiar to you?

Myth 1: Bosses Lie, and They Care Only About Themselves

This is true of some bosses, and smart people leave those bosses immediately. Most other bosses truly care about their organization's success, which helps their people make a living and learn new skills.

A company that I work with hit hard times in 2009, laying off most of its employees and draining the savings of the owners. The owner teared up as he described laying off fifteen-year employees. His face lit up as he described the joy of bringing them back to the company when sales improved. This story is about his face, not the employees. In fact, one of his prime concerns about his kids taking over the business is whether they have the same powerful empathy for their people (employees).

I am an old man now, and I have had a great many problems. Most of them never happened.

—Mark Twain

Myth 2: Process Improvement Beats Teamwork

The genius of process improvement is that process changes are independent of the people doing the work. Workers can be brought in from outside the process, and the process is available for them to implement.

The curse of process improvement is that it depends on the people to do the work the new and better way. Increased efficiency usually requires acute attention to detail, which comes either from years of experience or careful teaching. The reasons that process improvements don't stick are almost always about the people, not the process.

I worked at a loudspeaker manufacturing firm where the team lead turned the idea of process improvement into a game with his people. He played the game with me on my daily plant tour. I'd ask, “What's the improvement today?” He'd always have one. Always. More remarkably, most of the ideas came from his team, not engineers or outside analysts. I tell you this, not to push the tired meme that “the people know” (because just as often they don't), but because their leader turned their work into a game that gave them recognition every day. On the days where there was no improvement idea, he'd still ask about it, keeping it alive for the next day. Their work was way past following someone else's process rules; they loved the challenge of finding a better way. Oh, and their quality and efficiency rose to record levels!

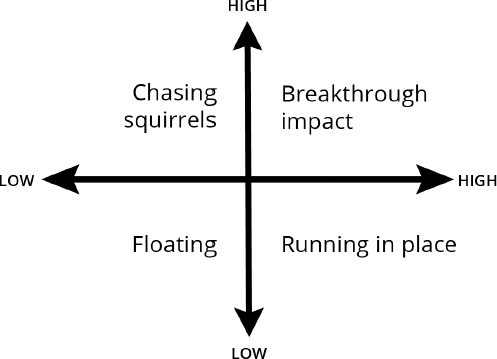

Myth 3: Inputs Are More Important than Outputs

Activity untethered to results frequently produces frantic action but no change. The worst example of this was an otherwise skilled production manager growling, “I want to see all the machines going up and down for the whole shift.” The result was that welders (the second step in the process) hiked all over the plant to find the next pallet of parts to assemble and weld. They were told that their slow welding was making the machines wait! Actually, what made the machines wait was a sloppy work schedule in the first production process in the plant. That process was laser cutting, and the guy leading the laser team grabbed the simplest job in the pile to do next, instead of choosing jobs to optimize plant throughput. When the schedule changed at the laser, the welders stopped walking and went back to welding, which they preferred. Both problem and solution were about the team lead's choice regarding work schedule. It was not about the process.

If people are rewarded for what they do, instead of for their results, it can produce a gauzy happiness with calls made, units produced, orders shipped, and so forth. An e-commerce client found customer call-backs rising, a sign of increasing customer dissatisfaction. Instead of scheduling more folks to handle the call-backs (more activity), the COO adjusted scheduling so that more people were available at peak call times. Callbacks dropped back into an acceptable range without adding people. More important, they took care of customers on time.

Myth 4: Analysis Beats Individual Behavior

Noise about benchmarking and big data obscures the reality that skilled sales people or internal leaders may find an 80 percent solution quickly, and delivering that solution produces progress and a sharper point on the next step to success. Most of the time, analysis feels good but doesn't speed the process of delivering real help to customers. It just reduces stress inside the company. Sometimes a beer is better.

Myth 5: Plans Before Execution Beats Execution to Build Plans

Although there are times that good plans beat execution, usually rapid execution will clarify needed adjustment to plans more quickly and precisely. This approach requires a sensitive balance of listening to customers and a willingness to adjust. It comes by watching customer results, not progress versus plans.

Myth 6: Metrics Provide Accountability

The power of good metrics is focus. Without commitment built on accountability, however, metrics soon lose their punch. A manufacturing company designed new metrics, carefully explained their sources, and posted them daily. One day, I asked the production manager what he thought of the metrics (they were aimed at him). He pointed to the executive conference room and said, “It's up to them!” His message confirmed that the correct data hadn't laid a glove on him, and he felt no accountability at all. As good as the numbers were, what was missing was the conversation with him about his role in moving the numbers and what it meant to the future of the company.

Myth 7: Exceeding Expectations Beats Meeting Goals

“Exceeding expectations” is lazy leadership, meant to substitute for crisp objectives about things that matter to employees, suppliers, and customers. The myth is that hefty promises pull top results with them. The reverse is usually the case, as explained by a veteran middle manager in a privately owned production firm: “We never had goals. The owner just said that he knew we could do better, as he called us to ‘exceed our customer's expectations,’ whatever that meant. What it meant to me was that we always fell short, no matter how hard we worked. It was a real downer.”

Myth 8: If You Put the Right People in the Right Jobs and Leave Them Alone, They'll Excel

This error comes from the well-meaning leader who has successfully built a thriving business from scratch. With growth and complexity come an escalating requirement for blunt communication and teamwork.

Being an able leader doesn't translate to making the right decisions in the high-speed complexity that marks all successful firms. Instead, preplanned processes and connections help folks to work together to get the right stuff done.

Myth 9: A Strong Leader Is More Effective than Delegation to a Team

This is true when the organization is small enough for the leader to know what everyone is doing. It's also true in times of extreme change (high growth, slumping sales, or a merger with another organization) for a short time (months). If the strong leader devotes herself to building a strong team early, the momentum of change can be amplified with improving quality. The secret is in the leader shifting focus to team effectiveness, instead of business effectiveness. If the leader insists on leading himself, the capacity of the business to grow will be truncated. High-growth markets will hide the limits of a strong leader, but competition or the eventual shift to moderate growth will slow business growth.

Myth 10: Department Excellence Beats Teamwork Across Departments

The basic truth is that all departments should have a hand in company success, or they should be disbanded. When there are fewer than twenty employees or so, communication is common unless there's a catastrophic personal collision. Folks see each other daily, and it's easy to keep up with each other in the course of walking around. Beyond twenty people, misunderstandings spike, regardless of motivation, style, or skill. The culprit is the very department targets that led to excellence. Folks are trained to do the core work of the department before anything else. The flow of work, praise, and job security is a flood of department tasks, with occasional links to other teams floating in the river like debris. Doubt it? Look around your office at lunchtime. How many folks are eating at their desks? Their vote is to spend their time on those tasks, not on other people, even though talking with those people would likely make their jobs easier or their results better.

Unless there is a mechanism for regular communication, silo thinking sprouts, even in companies with a hundred employees. That communication mechanism has to be automatic, simple, and clearly useful, or good employees will ignore it. The mechanism seldom is money. Instead, recognition and structured work time can enable it.

Myth 11: Bonuses Should Be Individually Crafted to Fit Each Department

This crazy notion feeds on the idea that folks in each department need special skills, so their bonuses must be individualized. But it's wasteful: Incentives should be tied to clear results, not individual skills. This is the signing bonus gone awry. If extra skills or work don't benefit customers and the company goals, it is waste and should stop.

The truth is that because all departments (and people) are needed for success in the company, measuring individual contribution is necessary but insufficient for calculating incentive pay. Instead, incentives linked to total company performance will pull your best people into working together for both pride and profit. Such teamwork doesn't require paying everyone the same, although that's successfully done in some firms.

One successful way to do that is to build a company bonus pool as a percentage of earnings, then allocate the pool based upon a mix of individual factors including salary or performance against objectives. It's relatively easy to show that all employee compensation rises as the pool enlarges, and quarterly pool reporting and public formulas for calculating the pool each month enable employees to calculate their personal bonus fund's growth.

Counterintuitively, because most successful sales people are “coin-operated,” their bonuses should be tied to their performance, calculated separately from the rest of the company, but paid from the company pool and reported (if not paid) quarterly or monthly.

HOW WE ACHIEVE MYTH RELIEF

Why bother with myth relief? Myths can impact the present and the future, so like putting steering wheels on cars, we'd like to set aside the dangerous myths before a damaging collision occurs.

Remember the four dogs? Three dogs knew they were running in a field, and the fourth dog acted like it was still in its cage. The difference was in their myths, wasn't it? Imagine if 25 percent of your people thought that the goal was profit at all costs, customer be damned! Those 25 percent create a riptide that dangerously slows your whole operation, like a surfer trying mightily to get past the rip and out to where the riding waves are. By the time she gets there, she's out of energy, and the next rides are lousy. And no one wants to be in the 25 percent that's aiming the wrong way!

Yes, that fourth dog is neurotic. A neurosis is an unconscious false belief about the world that seems real to its user. A false belief lives and has power because it's useful and satisfying, and the more it's invoked, the stronger it becomes. It also blocks a clear view of reality, when reality and neurosis clash. You, dear reader, are participating in this discussion with the neurotic belief that you don't have neurotic beliefs. Of course you do, on a range of topics. Much of the time they do little damage; sometimes they help (little white lies, for example), and sometimes they send you down the road to failure—at least for the task at hand.

If my myths mislead me, and your myths mislead you, then our company is full of people who are misled to some extent. These stories won't go away, but they can be powered down and allowed to linger at the side, untended.

As you might expect, there's a three-step process for myth relief:

- Identify them (the hardest part).

- Rate their danger potential.

- Erase or defang the most damaging.

Learn Your Personal Myths

Your personal myths are also called your cognitive bias. “Cognitive bias” is described by Richard L. Byyny, MD, as “a systematic pattern of deviation from norm or rationality in judgment, whereby inferences about other people and situations may be drawn in an illogical fashion. Individuals create their own ‘subjective social reality’ from their perception of the input.”2 These are often unconscious beliefs that a person isn't aware of and doesn't question, but that provide powerful guidance in behavior, judgments, and relationships. Sounds a lot like myths.

When you find yourself acting on a belief that defies available data, pay attention to the quiet alarms in your head or on your colleagues’ faces: likely there's a personal myth operating. Look at the data to see if you should drop it, modify it, or keep it. And sometimes there is no data check available, but the smart person stays open to the possibility that even cherished beliefs defended loudly may be untrue. Here's a simple personal myth check (no peeking): What percentage of Americans are vegetarians? *Answer at the end of this section.

Why look for your own myths? Myth energy can be so strong that consciously aiming it can make a striking difference in your life, happiness, effectiveness, relationships, and more. Aiming is no more than spotting a myth in action and doing the data check. If it's real, move along; nothing to see here. If it's questionable, ask if it matters to anything that you care about (your values, your company's success, the well-being of your friends or family, etc.). If yes, rebuild the myth on the data, and change what you're doing. If no, ignore it, and especially stop sharing it with others.

No one gets it all the time, but like the old baseball analogy, getting it right a third of the time pulls you out of an eddy of waste in your life.

Company Myth Finder

Answer quickly and honestly. It's your company, after all. Rate how each sentence below applies to your company now. Write your score on a separate sheet of paper using the following scale. If there's a myth that you think deserves attention but it's not listed, write it down.

1 = Seldom 2 = Sometimes 3 = Frequently

4 = Mostly 5 = Always

- Bosses lie, and they care only about themselves.

- Process improvement beats teamwork.

- Inputs are more important than outputs.

- Analysis beats individual behavior.

- Execution before plans beats good plans before execution.

- Metrics provide accountability.

- Exceeding expectations beats meeting goals.

- If you put the right people in the right jobs and leave them alone, they'll excel.

- A strong leader is more effective than delegation to a team.

- Department excellence beats teamwork across departments.

- Bonuses should be individually crafted to fit each department.

- I know I'm doing a good job because no one has chewed me out.

- Other [fill in the blank].

Ways to Use This Data

- Add suspected myths to the list.

- Ask key leaders and employees at all levels to fill out the Myth Finder.

- Send responses it to a neutral person to tally and summarize.

- Schedule a sixty-minute work session to discuss questions like these:

- What are the three most damaging myths?

- Which is the strongest (believed by the most people)?

- What are the facts to counter this myth?

- How do we communicate those facts?

- Do they justify a workshop approach? Present findings, present facts, discuss, and ask for actions outside the room. Use a workshop approach when the facts are either complex or unlikely to be believed (or cared about) if simply recited in a company communication (letter, talk at meeting, e-broadcast).

- Do we need a regular de-mything process in the company?

Pay Attention to Behavior

Where you see behavior that doesn't fit the data as you know it, do one of two things:

- Get the best data you can find to clarify reality.

- Ask the person what prompted them to do it.

If the data is unconvincing, then direct interviews will usually uncover the myth. With either tool, remind yourself that you're seeking what's real, even if it's not what you believe or prefer. The practice of seeking evidence will dissolve myths by itself, as it's observed by others. The truth may not set you free, but its power to simplify can be breathtaking.

For example, dramatic cuts in reimbursements endangered a chain of physical therapy clinics. They recovered by intensive myth-busting.

Myth: Therapists believed that revenue increases would require them to speed up. That would endanger patient satisfaction and treatment quality, the basis of physician referrals.

Myth-buster: When therapist treatment hours and patient satisfaction were posted daily in each clinic, therapists sought ways to move their results. When the therapists saw that they could get more patients to come to treatment just by helping them understand the treatment and asking how they were doing (relationship), their efficiency and cash flow improved dramatically—along with an increase in patient happiness (they measured it).

Replace Negative Myths with a DAC System

As you start noticing myths, go ahead and sort them into two piles: helpful and not helpful. This sort can be quick and easy so that you know which myths to reinforce with measuring or recognition, and which need to be stopped or changed.

Replace negative myths with a data, action, and communication (DAC) system. The core of this system is real-time data shared broadly and frequently in team settings whose purpose is to frame its individual responses. Its purpose is to shift all employees’ evaluation of what they need to do from their myths to actions built on a reality system. (There's more on the DAC system in Chapter 3.)

*Answer to special question: 3 percent of Americans are vegetarian.3

CHANGING OUR BELIEFS INTO VISION

I learned to windsurf with my thirteen-year-old nephew—in Kansas. He moved to Maui and became one of the top professional freestyle windsurfers in the world; I did not. With his windsurfing gear, he sails a wave, launches as much as twenty feet in the air to do aerobatics, and lands back on the wave. Like all acrobats (gymnasts, ice skaters, divers) he learns his moves like this:

- Picture each step.

- Try it.

- Clarify the picture.

- Rinse and repeat—hundreds of times.

Yes, his moves are a string of pictures in his mind. His head moves toward the pictures in sequence, and his body and windsurfing gear follow. His pictures are his “vision.” It has pulled him from a kid in Kansas to a world-ranked competitor in an extreme sport.

A vision is a picture of the future. The best are emotional and specific. Done right, it can power a great organization by aligning people's emotions, analysis, and actions toward the same end. It's a common concept that's seldom used well, if at all, because it's easy to create and hard to live daily.

Stanford professor David Cheriton and Sun Microsystems cofounder Andy Bechtolsheim met on David's porch in Palo Alto in 1998 to hear the ideas of Larry Page and Sergey Brin about their page-rank algorithm. Those ideas vaulted into a vision so compelling that Andy ran to his car to get his checkbook. He and David each wrote a check for $100,000 to Brin and Page, becoming the first major investors in a company that became known as Google. That $100,000 has grown to more than $1 billion.

What was that vision? It was access to mind-bending amounts of information instantly for everyday users, including students writing a term paper. Its basis was a switching technology orders of magnitude faster than anything then available. Dr. Cheriton says he has “a belief that if you are providing real value to the world and doing it in a sensible way, then the market rewards you.”4

There's the vision: It's not's the faster switch; it's the instant access to information for millions of people.

It's easy to stop at the billions in value at Google. The point is the power of the vision, however, because it ignited a future beyond imagination. Without the vision, powered by David's deep knowledge of switching algorithms, there's no explosion of technology. This process mirrors the power of vision. Vision correctly used literally means to make a picture of our organization's output in the future, exploding like the Big Bang. Don't miss the “exploding” part. That's numbers of people who were captivated enough to move toward that vision, and their captivation became Google!

What's myth got to do with vision? Myths provide these three essentials for folks who are serious about reaching their picture or their vision:

- Myths (beliefs) often carry a knockout punch of energy, essential for the slog to the finish line of each part of your vision. My nephew can see himself doing his entire move—a complex ballet in the sky with windsurf gear attached and coral reef in a foot of water below. That picture picks him up when he falls and sails him out to try again.

- Myths help you drop activities that don't move you toward your picture.

- Myths help you create a compelling vision that you can't wait to experience. My nephew would say that pulling off the move fifteen feet above the water and landing back on the wave is a rush that defies description. The myth is that he has already done it; the experience is his addiction, and he can't wait to try it again.

WHY HAVE A VISION?

An organization is a group of myths trying to go somewhere together. Each of us is a bundle of myths squinting into the daylight to find our paths. The first function of a company vision statement is to corral the hundreds of myths running around via its employees, and aim enough of them in the same direction to enable positive movement. A vision can be the laser-like alignment that winning organizations and teams need for sustained success.

Myths Drive Future Outcomes

In fact, the power of myths is that we use them to help control our future. The very uncertainty of the future is both a curse and a gift, depending on your personal myths. The outcome of an organization is powerfully impacted by its myths and their translation into personal myths by its people. That personal translation becomes the myth of each employee, powerfully driving individual behavior, and by extension, the performance of the organization.

So we live among two sets of myths: organizational and personal. Each myth set is impacted by past and present, as well as the other myth set, so it's no wonder that we're sometimes unclear about our myths. As an employee, my behavior at work is impacted by my myths and company myths, as I understand them. Myths are a powerful driver of company performance, culture, and aspirations. That swirl of myths can either be a laser or a lightbulb, depending on how leadership directs it.

How to Harness Myth/Vision Power

Sadly, the word “vision” is so overused it's like yesterday's coffee: dark, bad-smelling, and offering an unpleasant diversion from today's opportunities. Picture a vision statement (if you can remember one) from an organization. Too often, it is standard words in a standard frame in a standard place that sleeps like a Harry Potter painting. But the vision doesn't come to life. Ever.

How do you bring your vision to life? Invite your people to hop on the train that's going toward the vision. Their myths and wishes painted that vision picture because they want to go there, so make it explicit.

For example, we can harness the myth-building strength of our people toward our purpose and create powerful new myths about our value story by asking questions like these:

- What could we do for our customers?

- What is the value of each product or service?

- Will the value support a price that our customers will pay?

- How do we refine the value and our costs into a model that works for all of us?

- What value story can we create for our employees and our customers?

Yes, the “value story” is a myth, but a constructive one. It moves from story to myth as your employees live it, struggling with the hidden problems, reveling in the surprising satisfactions—and telling stories about problems solved and customers served in group discussion.

When you combine a myth-charged vision with a value-story myth for your organization, you've created a view of the present and the future that your employees can be excited about. Like our windsurfer, the gleam in their eyes is fueled by myths that they've chosen, and they want to be back on the wave as soon as possible.