Chapter 9

The Talent Quest

Talent is the engine of the enterprise. More than the right seat on the bus, it is matching real output with company needs in real time. Change now requires broadly skilled individuals playing on broadly skilled teams to surf the tsunami of change that swirls about us even now.

Before you assume that “talent” is something that only big firms do, consider this: The Wall Street Journal reported on January 31, 2018, that Amazon, JPMorgan Chase, and Berkshire Hathaway “plan to form a company to reduce their workers’ health costs.”1 Instead of emphasizing the technical approaches one would expect from such firms, Berkshire chairman Warren Buffett said they believe “putting our collective resources behind the country's best talent” can deliver on such a promise. Look again. One of the nation's stellar collections of technical expertise is talking about talent first! Draw your own conclusions, but if folks who can buy whatever they want are talking first about talent, there must be something there, and of course there is.

RECRUITING TALENT

Who does the organization appeal to? Much is made of the appeal of organizational culture to attract the kinds of people who will power its success. It may be argued that there are two kinds of organizational appeal:

- Type 1: The opportunity to grow and be promoted to positions with more power, influence, and money.

- Type 2: The opportunity to enjoy meaningful work with peers who value each other, in settings that provide the autonomy, mastery, and purpose that build meaning.

These appeals broadly define the hopes and expectations of two types of employees. One gladly seeks the risk and discomfort of moving to a new position before thoroughly mastering the old. She or he thrives on change and increasing responsibility, and in fact, measures success by the speed of those changes. The bent toward change, growth, and promotion provides the fuel for the constant improvement that marks most industries today. These employees are fewer in most firms, but essential to survival.

The other employees are the folks who get most of the actual “work” done. They value more predictability and safety, will devote years to mastering their skills, and will be drawn to organizations that recognize their contributions regularly. Their ability to find other jobs can be more limited because their need for security makes changing jobs uncomfortable.

Cy Green, legendary former president of billion-dollar retailer Fred Meyer, explained these differences to me in a conversation that began like this: “If there's a problem with a store employee, I'll likely take their side.” Paraphrasing, he continued, you don't need the protection, you're willing to take career risks, and you have the resilience to bounce back. They will trade new situations for the safety and familiarity of work that they know they can do well. They often can't protect themselves very well, so I'll be happy to do that. We need both of you.

Recruiting is wrongly defined as searching for the “right” kinds of talent, when it really is about what is needed along a time continuum from now into an uncertain future. These categories of positions need to be made explicit in job discussions, if not in position descriptions. Also, relying on past job descriptions to define the next position is seldom adequate because it looks to the known past more than the possible future.

A better recruiting question: What will this position need to deliver in the next three years? A job description starting from that question has a better chance of delivering a successful employee to almost any position.

The debate about whether to fill the position or promote from inside is over. The recruiting sequence for success is:

- Define the position needed in the coming three years.

- Prepare for an external candidate search.

- Use search criteria to evaluate internal candidates.

- Seek outside candidates when no adequate internal candidate is found.

A new twist: The appeal of company culture is personal, but it extends beyond the employee setting, and rightly so. This culture has expanded outside organizations to their locations and the life that such a location offers. Urban studies expert Richard Florida (The Rise of the Creative Class) documents in exhaustive detail a relatively new and powerful phenomenon: It is common now for workers to choose a job because of its location. That's the reverse of patterns that have existed since the American Civil War (1860) when workers moved where the jobs were. The underground railroad provided a path, not just to escape slavery, but to find jobs and the income that provided for the kind of life that those folks sought.

Today, more than even five years ago, prospective employees ask questions like these:

- What kinds of people work there?

- What's important to folks who work there now?

- What kind of place is it located in?

Successful recruiting will have prepared answers to these questions that anticipate the preferences of desirable employees, not only about job specifics, but also about these softer characteristics.

New data from Stanford Graduate School of Business suggests that adaptability may be as important as cultural fit over time at a firm. Amir Goldberg of Stanford and three coauthors reviewed more than ten million internal emails from a technology firm over five years, tracking cultural fit with linguistic analysis: “Language use is intrinsically related to how individuals fit, or fail to fit, within social environments,” and, “what predicts who will stay . . . leave . . . [or] be fired is . . . the degree to which they adapt,” Goldberg says.2 “Adaptability means working effectively within multiple departments, locations, and company units over time.”3

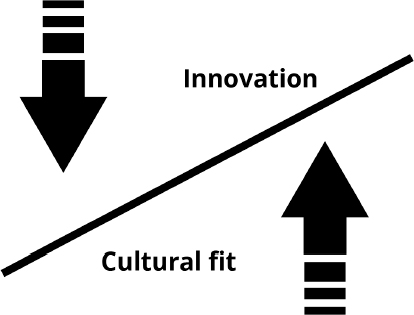

There is always the challenge of balancing cultural fit with innovative drive, but the best answer seems to be the ability to shape the innovation to enable the culture to embrace it well.

Increasingly, I see leaders who are reluctant to move aside employees in critical positions when they are no longer able to perform as needed. Instead of demanding excellence from each of their people, especially leaders, a combination of avoiding pain and wishful thinking perpetuates problem performance. The cost to company performance is high, but that pales beside the damage to the morale of other employees and equally to the struggling employee. Usually, the failing employee knows they are falling short well before the boss is ready to talk about it, producing fear and destroying the self-confidence that's essential in any position and to living a life with some meaning.

Here is a way to approach such a problem situation with these questions, talking privately with the employee and listening especially carefully:

- How are things going?

- It seems like things are a bit of a struggle right now.

- How is it for you?

- Would you like to consider a different position that would be more comfortable for you?

- We can help you find it, write a letter of recommendation listing your considerable skills, and support your job interviews inside or outside the company.

- Would you like to consider that?

That discussion has produced tears, relief, and gratitude, sometimes in just a few days.

Recruiting is mischaracterized as a search process. It's mostly not, but instead it is about clarity and agreement among key leaders about exactly why the position is needed, what it should contribute, and then what the core attributes of the employee might be. Almost always it's better to hire for attitude than for experience, even when there is a core of technical skill needed. After all, your most skilled people learned what they know; they weren't born with it. If they can learn, so can a new person, and a proven learner has much higher value now and in the future.

SUSTAINING AND DEVELOPING TALENT

Sustaining and developing talent demand similar activities. Both thrive with simple, “on the ground” programs, rather than sweeping promises. Often the headset of top leaders is a problem, with beliefs like these (followed by a rebuttal):

- What we have is working fine. Tomorrow will be different, and if our incumbent is just keeping up now, he'll drown in the flood of the future.

- The risks of bringing in a new person are too high for us. Not developing people for our future is a bigger risk than the risk of a hiring failure.

- We aren't good at training or developing people. Begin to learn by finding a leader who is good at it and tasking her to teach others.

- We need the right person right now. If you're saying this, you're already too late. Patch together temporary operations support until you can hire the right person.

- I don't see a person in the company who can fulfill the position. Shift your focus to aptitude and drive instead of skills and experience.

- Hiring is much too expensive. If you're considering hiring, the need is likely deeper and more acute than you realize, and the comfort of waiting will be replaced with declining results. Which heartache do you prefer?

In my work coaching senior executives, a surprisingly pervasive problem is unwillingness to delegate and demand performance from key reports.

The monkey on your back is a metaphor for taking on a project. Many people will try to hand the monkey to their boss (“How do I do this?”), and their boss compounds the error by taking the project (monkey). That reinforces these destructive messages in both people:

- I'm better at this than you are.

- It will take you too long to learn to do it.

- We can't afford to risk this project on someone like you.

- It's faster to do it myself.

Is the damage worse to the leader or the subordinate? It's a tie of bad news. The leader retrenches into familiar work instead of doing the less familiar but higher impact work that his job calls for. The subordinate hears denial of confidence in him, a narrowing of his responsibility to familiar work, and reduced chance of growth in skill or responsibility in this position. The ensuing weak performance is disastrous to the leader's results and career promise. The subordinate may recover faster, if she promptly moves to another leader and lets go of the bad experience.

Delegation can create a faith gap, where the leader lets go and waits to see if the employee picks up the ball well enough and soon enough. The blind spot seems to defy logic. If a leader has four direct reports of adequate competence, he can delegate and monitor the performance of all four in much less time than doing it himself. Instead, he will micromanage parts of projects to “be sure that things are being done well”—code for doing it his way. This behavior drives away top people and limits the performance of the team and the leader. It's logically crazy, but it's driven by feelings, not logic.

Consider levers: Bulldozers, tanks, and other vehicles on tracks steer with a pair of levers that control the speed and direction of each track. Moving the levers works like a steering wheel on steroids, multiplying the driver's power. A leader's people are like those levers. They are the direct link to the work that needs to be done and to how and when it's done. Yet this logical picture sweeps past many leaders who are in love with their task skills.

A CEO of a midsize software business was a brilliant sales leader. Sadly, when his very competent chief revenue officer tried to review a plan with him, the leader would pick up his pen to scrawl new ideas and make changes to the CRO's excellent plan. The differences in approach weren't enough to justify the disconnect with one of the most critical leaders in the company. He went away fuming and disheartened, depending on others to restore his confidence and excitement about his work (which was indeed exciting in every good sense). It took months of work and discussion to repair the breach in the relationship from the CRO's side.

The problem with recognizing poor performance isn't what to do about it, it's calling it out as a problem that needs attention. The potential upset with another person, and perhaps a gap in the leadership roster, will pull the problem to the B pile for another day. The answer for a leader is to ask the subordinate leader directly about performance data. That moves the discussion to the data and then to possible next steps, which boil down to train or replace. When the subordinate leader repeats this error, it's time for focused coaching on the topic. “Focused” often means going to an outside coach whose focus can prompt real change.

My wife repots her orchids after they bloom. They return with a rush of new blooms, often bigger and better than before. Who needs repotting in your organization? Repotting can range from a change in subordinate to a gain or loss of a responsibility to a challenge to develop a subordinate to be ready for the next position.

Mentorship is another powerful concept that's misunderstood. It can be useful to encourage diversity or to help other younger executives begin to understand how to be “seen” and appreciated by top leadership in a company, but that's not it's primary power for retaining and training people. As Sheryl Sandberg, Facebook COO and author of Lean In, says, “So shift your thinking from ‘If I get a mentor, I'll excel’ to ‘If I excel, I will get a mentor.’”4 People in any organization who do well for the goals of the organization will be noticed by others. That opens the door to working on a project or a presentation with a potential mentee or mentor.

Robust mentorship can provide frequent recognition and challenge to folks whose daily and weekly work may not provide much of either. Recognition and challenge with support are essential for building morale and hope—and those are foundations for great performance.

The other secret of a robust mentorship program, besides faster and deeper development of subordinates, is the leadership development available to mentors. It comes in small enough bites to make it useful. Leadership is significantly about influencing other people, and mentorship is the ideal way to test new skills with low risk and prompt feedback. Yes, mentorship is a partnership if it's to be successful. If either partner decides that the wisdom resides in them, it's game over and time to move on.

Carlos Slim, head of Mexico's largest telecom, is one of the world's wealthiest men. His personal wealth has recently dropped 20 percent since AT&T has entered the Mexican market. Ironically, twenty years ago he taught (mentored) the business to employee Randall Stephenson, now CEO of AT&T. Mentorship power, indeed!5

The basic prescription has two parts:

- Spend more time and money in recognition than compensation.

- Teach delegation as an active requirement of leadership.

Recognition tops every study on motivation I've ever seen (provided basic compensation is fair). Make the skillful practice of recognition as vital as making the numbers for every employee. Stop the speeches and make active recognition a daily requirement of employment. If you truly don't know how, ask a first-grade teacher how he does it. Better yet, watch a class and see it live. It's mostly a habit with a tiny bit of skill.

The “how” of delegation is more particular, but the leadership directive is to bring it alive. Every person who supervises another person should be able to answer this question at any time: What have you delegated today? Here's a simple delegation framework that works for almost anyone. Skip a step at your peril.

THE DELEGATION FRAMEWORK

- Name the task.

- Name the leader.

- Hand over the entire task to a person or a pair.

- Check for understanding: “What will you do?”

- Ask how they will measure progress.

- Ask what resource (if any) they will need.

- Ask for a first report back date (e.g., “Let me know Friday how it's coming.”).

- Ask for a completion or substantial progress date (e.g., “When do you think you'll finish?”).

- Be available to help. If there's silence for a week, ask if help is needed.

- After they've hit some of the targets, invite a brief update to the management team. (Optional)

SHARE THE TALENT: EMP LOYEES HELP EACH OTHER TO GROW

Sharing talent is not exclusively an HR function. It belongs to line management everywhere as they are the ones always asking for more people, better people, or more machines. Most people love to be recognized, and being asked to help is a high compliment—so ask. But ask for help instead of assigning a task: “Would you help me sort out this information?”

Model Two-Way Communication

Even though top leaders are regularly quoted as saying, “I learn more from my people than they learn from me,” most discussion about communication focuses on a single direction, usually down (from leaders to subordinates). Up is better than just down, but two-way communication is even better.

The four stages of communication:

- None: “You know what to do.”

- Down: “I know what you should do.”

- Up: “Here are ways to improve.”

- Two-way: “Let's attack it together.”

- What's a leader to do?

- Institutionalize: Make it “something we do here.”

- Check: Ask, “What ideas have you gotten from your people this week?”

- Recognize: At every all-hands meeting, recognize one pair that's done it.

- Include outside employees in management team meetings as observers.

More Simple Tools

These tools work if you rise from your chair and do them.

One that's very effective is regular skip-level visits by leaders. The rules:

- Go see folks who work at least one level below your direct reports.

- Ask them up to three questions:

- What are you proud of?

- What makes your job hard?

- Who helps you?

- Take brief notes.

- Listen. Ask questions only to help you understand.

- Offer no direction.

- Find one good thing they've done and praise them on the spot.

- Practicing one-minute praising is another effective technique. It's simple, but details are everything:

- Praise immediately.

- Stop and face the person; a drive-by doesn't work.

- Look into their eyes, and see if you can see who's in there.

- Praise a specific act. Name it.

- Admit how it makes you feel: pleased, relieved, proud, etc.

- Pause. Count to five to let it sink in.

- Thank them.

- Ask them to keep doing it.

- Move on. Don't dilute the moment with any comment.6

The excuse “I don't praise much” exists in many forms. Skip the psychobabble about why, and just make it a job requirement. Here's how:

- Approach it like any other high-value team responsibility.

- Make it an annual goal in your planning session.

- Quantify what a good job looks like (e.g., five a week, one a day, etc.).

- Provide brief hands-on practice for every leader.

- Require an action tally (how many) as part of the agenda for every one-on-one.

- Post weekly results by department, perhaps number of praisings as a percentage of number of employees.

- Recognize praising expertise in all-hands meetings.

- You get the idea. Instead of a limp, “You all know this is important,” raise it to the level of a major initiative.

For those who demand an ROI, explain that the best research shows that recognition, especially public recognition, ranks way ahead of pay and bonus for motivation. The exception may be salespeople, but because the requirement for success is always fair pay as a hygiene factor, simply pay salespeople fairly and add praise on top, like the cherry on a hot fudge sundae. Of all people, salespeople are generally most motivated by praise and recognition, so what's to lose?

In short, the free investment of regular praise will boost the numbers. We're awash in studies, so instead of reciting another one, I dare you to find a reputable study that proves that money beats recognition. There will be a prize—perhaps recognition on LinkedIn.

For a simple recognition booster, tie the praise to a specific impact on the business, such as customer service, quality, cost, pricing, or efficiency. Most employees are deeply invested in the place where they work, and that investment will boost the power of recognition.

Robert MacLellan, founder of the remarkably successful Pacific Coast Restaurants, will enumerate “free” actions by restaurant staff that played a significant part in their success. For example, a chef may not yell at a server, ever. There is one chance, and then the chef leaves. Why? Who wants an upset server at your table when you hope to enjoy a meal?

Or consider the bartender story as told by Robert MacLellan (a bit longer, but worth it). Picture yourself in the far corner of a bar just as happy hour starts. A man walks in, sits at the end of the bar. Bartender walks over, smiles, asks four questions, listening between each one: “Where are you from? What do you do? What brings you to town? What are you drinking?” Soon a woman walk in, sits at the bar (you guessed it) as far away from the man as possible. (Robert's translation: If an unaccompanied man sits down in a bar next to an unaccompanied woman, or vice versa, there is immediate tension and discomfort, usually in both folks . . . unless there are no other seats available.) Bartender repeats the same questions with the woman. After a bit, the bartender walks over to woman, picks up her drink, starts moving toward the man, saying, “There's someone I'd like you to meet.” Woman obliges, bartender seats her next to the man, introduces them to each other by name, where they're from, what they do, and why they're in town. They start talking. Now, it's not at all what you think. There's no hanky-panky. Instead, the customer experience is that it's a friendly, safe, pleasant place. The bartender repeats with other customers. After some weeks, people ring the bar four deep. They love coming there to talk with their friends! A group that met at the bar develops and starts a tradition of traveling together!

What's the point? Try treating your people, all your people, as folks that you like and admire (even if you must pretend). Pause occasionally and listen to them. Just listen, nod, smile, and look for reasons to connect with them or like them. That's all. That's a rich recognition that's free and makes a huge difference in their day-to-day work at your company.

Try Forced Growth

My early training included moving to a new assignment well before I thought I'd mastered the current one. Admittedly, I love a challenge, but the result was high-speed learning, a regular challenge, and pride in what we accomplished. I was to design and install a bakery concept in a major Chicago food retailer that would “be as good as the best Chicago bakeries, and break even.” That was the assignment. As a kid from Portland, Oregon, I had never encountered Danish dough, let alone artisanal bread or water injection ovens. The learning was a doorbuster for the rest of my life: I could help people with deep expertise apply themselves to a larger project and do it successfully. We designed and then built twenty-nine bakeries before I moved on—and they were magnificent! I'm still proud of what we accomplished, and there was no bonus or special compensation, except my pride in our team and our bakeries, which survives years since!

EVERY EMPLOYEE AN OWNER

One of the company owners that I worked with for several years periodically said, “This would be great if it weren't for the people!” Now, he likes people a little at a time, but he hates confrontation or disagreement. More accurately, he feels flummoxed when he runs into it, doesn't know what to do next, and worse, doesn't know how to prevent it, so he runs away from it. His answer regularly was, “If everyone just acted like an owner!” I think he missed the irony, because he's the owner.

The real point is about motivation and behavior, however. And here's the fantasy, summarized: If I could just inject motivation into people, things would work better (and smoother). This is naïve.

There is no tool, system, practice, culture, or magic that will motivate people; and those who are not owners will not be motivated like an owner—even broader ownership. That's like saying that people should act like astronauts. The problem is that most people will never be in a space station, and they won't be owners of the place where they work.

How to motivate employees? Here's a starter list:

Pay for the job, with minor adjustments for performance and skill. Pay them at least market rates (salary) and provide for regular reviews to see that their pay links to market pay. Don't pay a high-potential person for their future contribution, except in the initial hire. Make it clear that compensation increases come from their contribution to the success of the business. And change the dialogue from pay to compensation so their bonus and benefits are included. It's obvious to your accountant but not to most employees because what they regularly see is the cash part of their paycheck.

Allocate bonuses by the ratio of individual salary to total salary dollars. Develop a company-wide profit sharing system that allocates a percentage of company profit to the company profit pool each year, and avoid shifting cash needed by the business to the profit pool. Report results quarterly, including individual shares. Either pay all annually or pay 30 percent to 50 percent of the profit sharing earned in the current quarter and the rest at year-end. The best plans make the first 50 percent firmly the employee's, without claw back. There are two motivators: the quarterly check, and the report of the company's profit pool progress with monthly financials. If possible, use a formula that allows all employees to calculate their potential share.

The only exception to such a plan is for salespeople who may be so driven by sales that they'll perform better with a commission plan. Do not cap it, because the more they sell, the more the company makes, if there's a gross margin “brake” on their commission, and they are only paid after each commission is fully collected.

- It's more believable to observe that all departments contribute to the profit from each order than to try to motivate people on individual or department performance. The logic is that no one employee in a company can function without the support of all the other employees. (If you have employees that aren't contributing, train or replace them, or eliminate their jobs.) Multiple plans invite disgruntled debates about favoritism. If you must pay incentive pay to departments or to salespeople, make a two-tier plan that's partly driven by their department and partly by company results.

- There is no holy grail. There is no perfect plan, so seek a strong plan, not a perfect one.

- Match their interests and aptitudes to their current position and future positions. Install a system that requires evaluation with every employee the match with current and planned next position every two years at least, if not annually. Replace the hackneyed annual performance system with this current and future match system. This requires:

- A baseline profile of each employee's interest and aptitudes.

- A system of matching and evaluating.

- A conversation with the leader and her leader about the next position for each employee, and one or two skills to consider when that position becomes available.

Use KPIs aggressively (see Chapter 3) to frame what is required to make the week and make the month.

Remarkably, this links to recent research about athletic performance. Key takeaway: Physical conditioning is essential, but world-class performers find another gear as they approach the finish line (end, target). That's in their heads, not their bodies.

The crucial first step is to accept the idea that your perceived capacity for endurance (or speed, or attention, etc.) doesn't always correspond to any physiological reality. The most compelling research example is a French study published in 2017 in Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise.7 Cyclists raced an avatar that they thought was set to match their best times. In fact, it was 2 percent faster, and they matched the new, faster time. When it was set 5 percent ahead, they couldn't keep up.6

Translation: You don't know what you're capable of, especially in bursts, and the end target (end of the race, end of the week at work) is essential to fuel the added performance.

Talent tip: Do you have your top two people in the highest-impact positions in the company? Those can be either permanent or temporary assignments. If not, what will it take to put them there?

The behavior that follows strong motivation is not the result of careful hiring (although it helps). It's a reflection of leadership that trains, recognizes, and appreciates excellent performance, and seeks to provide all three to every employee. If the pride of accomplishment doesn't provide motivation (and sometimes it doesn't), the recognition frequently will.