Chapter 2

The Power of Pairs

This chapter will shift the focus from teamwork, which is common, to working in pairs, which is the connective tissue of winning organizations. Pairs are hidden in plain sight. Much is made of teams in organizations, sports, work groups, school classes, and so forth, but the pairs in the groups are seldom noted. Those pairs offer remarkable leverage to their teams, and to their individual members as well. Why is it that descriptions of teams often talk about pairs (catcher–pitcher; quarterback–receiver; research partners; writing partners) as they analyze success or failure?

Pairs are our most familiar relationship, perhaps because we often begin bonding with a parent within hours after we're born, even before we're aware of it. The strength of that bond can be a major source of emotional strength through life. That attachment is so familiar, and so vital, that it's no surprise that pairs remain a source of powerful emotional connection.1

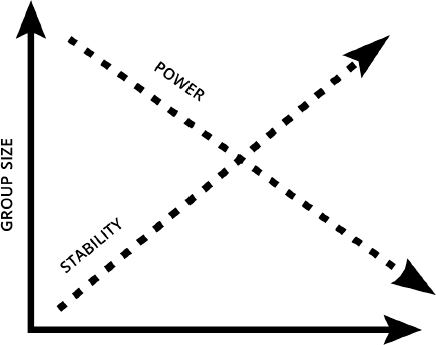

Pairs, or dyads, offer the strongest emotional connection but are the least stable of all group sizes: If one member departs, the dyad ends. German sociologist Georg Simmel (1858–1918) discussed the relationship of group size and group dynamics. In summary, the larger the group, the more stable, but less emotionally connected; the smaller the group, the less stable, and the stronger the emotional connection. To test this, consider your emotional connection to your spouse or partner as compared to your emotional connection to your work group. The fact that this exists in plain sight doesn't hide its power, however.2

Now you know why so much is made of team building. Some pairs in a group will have such powerful connections that their behaviors will lean toward each other, instead of group goals. Why not reverse this? Instead of focusing only on the team, why not focus on the power of pairs in the group as well? The deep emotional power of pairs can be a remarkable source of good in groups and in the organization. It can also be a powerful block to progress if not managed effectively.

Consider that in a group of eight, there are fifty-six pairs of people in relationship with each other. The connections aren't all of the same strength, of course, but their existence underlines the power and challenge of successfully leading a group. Why not recruit the power of pairs to boost the effectiveness of any group in an organization?

Empowering pairs can be most effective in strong groups, often characterized by shared goals, frequent feedback on performance, and the fact that success demands all of the team, not just a few. The undesirable opposite of a successful team is a group dominated by one or two “A” players who act like their performance confers power, recognition, and a senior place in the organization. “Taking the team to the next level” can become a reality instead of a tired cliché by empowering the natural pairs in the group. Their stronger emotional bond can power enhanced commitment and performance, within group goals.

It is a myth that most leadership work happens in groups. Some does, of course, but much coaching, direction, evaluation, and teaching happens between two people, such as a team lead teaching a work technique to an employee, a supervisor helping a manager clarify priorities for the coming week or month, and so forth. These interactions are a significant source of skill-building among managers and are a primary determinant of attitudes, including motivation and feelings of safety, risk, and appreciation. For example, the experiences of self-actualization and recognition can be much more powerful motivators than the modest increases in salary or bonuses available to most employees.

LINKING PEOPLE EFFECTIVELY

Since pairs can affect each other so powerfully, why not take advantage of strong relationships that already exist, and work to reduce the forces that push them apart? Begin by rating pair relationships by using this pair strength measure:

- Strong pair—1

- Negative pair (dislike each other, or one likes but the other dislikes)—2

- Neutral—3

Start with your leadership team because their impact is immense on the organization. List each member. Then pair each member with every other member of the team, one pair at a time. Observe their behavior in meetings and ask these questions:

- Who is always supported by whom?

- Who chooses to work with whom?

- Who avoids whom?

- Who fights with whom?

Use your ratings to find strong pairs and pairs that work together poorly.

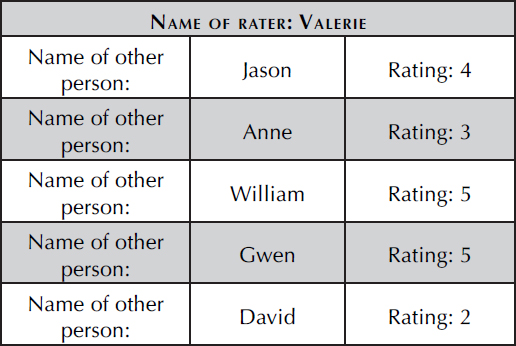

Next, perform a confidential Individual Trust Audit on your leadership team, using a trusted outsider. Ask each person to rate every other person on a scale like the following example in Figure 2.2.

Instructions: Rate each person in the group on how much you trust them, using a scale where 1 = I don't trust them, and 5 = I thoroughly trust them.

Individual Trust Audit Example

Note: Visit grewco.com to download Individual Trust Audit forms to use with your team.

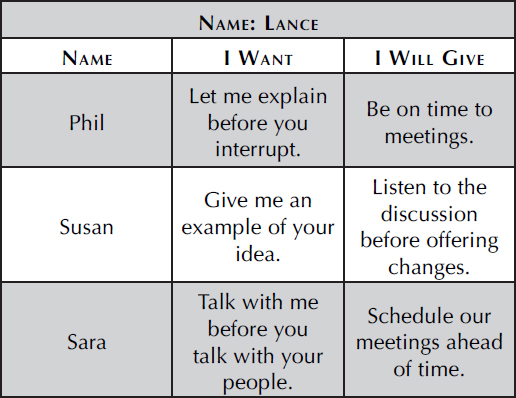

Use the Want–Give Review as a discussion opener to begin fostering trust among pairs in a group or team. The form is available for download on my website (grewco.com), and Figure 2.3 on this page illustrates an example.

Ask each person to fill out both columns. Group in pairs to discuss their answers with each other for seven minutes. Rotate pairs to cover all combinations in the group. For added impact, bring the group back together. Ask each person to share one positive idea that came from the exercise. In six months or a year, repeat the exercise with the same team. Ask each group member to share a significant change from the earlier exercise.

Want–Give Review Example

For strong pairs, assign leadership of initiatives that have a high-value, short time horizon, such as:

- Complex initiatives between departments.

- Modeling processes to be copied by others.

- Process improvements.

- Prototyping management of new initiatives.

- Developing high-potential junior executives by working together (make development explicit).

- Accelerating product development.

- Modeling examples of improved presentations to others, such as customers, process teams, other executives.

For negative pairs, when assigning projects or ad hoc work, either avoid putting these folks on the same team, or make the team at least five people to dilute their impact on each other.

Work to reduce negative perceptions:

- Interview each person separately about perceptions about the other.

- Share the interview with the person described.

- Modify the perceptions of each person with your own experience.

- Add positive characteristics that you see.

- Invite response, looking for willingness to improve in a specific area.

If you observe that this exercise doesn't reduce friction to an acceptable level, counsel each person individually about the impact their behavior has on the team and the company. If necessary, move one or both to other positions, or remove them from the firm. The message, sent by example, is that the company values working constructively with each other, even when friction occurs.

THE EMPATHY CONNECTION

Empathy is such a critical leadership tool that we'll pause to learn about it, learn how to expand your own empathy, and how to use it to improve your leadership.

Empathy is not weakness or emotional diversion. It's an essential skill for any leader, or any person seeking to work or relate constructively with another person. “No less a hard-muscled body than the US Army, in its Army Field Manual on Leader Development (one of the best resources on leadership I've ever seen) insists repeatedly that empathy is essential for competent leadership,” says psychiatrist, psychoanalyst, and leadership expert Prudy Gourgechon, MD.3

Let's clarify what empathy is because it's one of those words that is commonly used incorrectly. It's the ability to put yourself in another person's shoes to understand their reaction. The tricky part is that it means putting yourself in their shoes and understanding how they would react in their shoes, not your shoes. Most of us confidently assume that we know how another is reacting because we put them in our shoes: backward and often way off the mark.

Empathy is “knowing (and usually sharing) the other person's experience, perspective, and feelings.”4 It may or may not include your own feelings. This “knowing” means that you can imagine what's going on in the other person's thoughts and feelings, although imperfectly. It is a “neutral data gathering tool”5 that helps you understand the people you interact with. Sympathy is a feeling of care and concern for a person. Empathy is recognizing and sharing his or her emotions and perspective. Empathy can be summarized as “feeling with.” Sympathy can be summarized as “feeling for.”

Empathy does not include a psychiatric evaluation or definition, or a peering into the mind or soul of another. Instead, it's a connection in a specific circumstance that provides data for communication, evaluation, decision-making, and leadership. An extreme example is pairs of expert figure skaters, who anticipate each other not only when their routines go well but also when they need to adjust to a misstep.

When empathy is present in a relationship (a pair), both tend to feel safer and more confident because the other person seems like an ally instead of a competitor or antagonist. Notice that this safety is not the product of shared analysis, goals, or values. Instead, it's built on the expectation of a nearly automatic benefit of the doubt. Practice together is powerful, and it also builds the kinds of emotional connection that enables both to perform better together than they would have individually.

How to “Get” Empathy

The brain uses a “system of interconnected brain structures including the amygdala and orbitofrontal cortex to help process emotions, make decisions, control impulses and set goals.” These areas of the brain are plastic, that is, they can be changed by more intensive use, just as most brain cells can be.6 The capacity to develop empathy is available to most people, although it varies in strength.

Empathy involves different experiences with each person. The observational skills can be the same, but the individual's experience will be her own. Here are some cues to begin practicing. Before you start, give yourself some space away from the crush of the day so that you'll be more personally aware of the other person. In each case, focus on one person and pay close attention to cues like these to help answer the question, “What could they be feeling now?”

- Gaze: Attentive, wandering, looking away.

- Posture: Leaning toward the speaker, leaning away, slumping.

- Tone of voice: Animated, neutral, monotone.

- Questions: Perceptive, frequent, and intense; or commonplace repetitions.

Another way to think about it is to ask yourself, “Is this person interested in me and what I'm doing, or are they just going through the motions?” If you can't tell, your empathy detector is closed. To open it up, check yourself: Are you nervous, trying to push your point of view, looking down on them, feeling superior, or rushing to finish a laborious conversation? This checking yourself is called “countertransference,” or observing the ways that you react to another person. Those reactions can be powerful diagnostics for your own skill-building. Unless you are genuinely interested in the other person, you'll miss much of what they offer, let alone have limited ability to team up with or even influence them.

How to Use Empathy

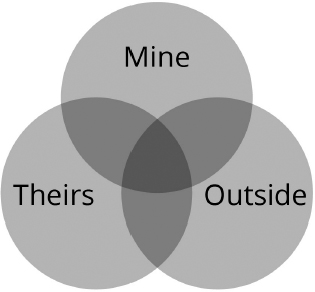

Problem-solving. Problem-solving with another person involves a data triangle: feelings, thoughts, and facts that reside in three areas—your mind, the other person's mind, and external “facts.”

For many questions, better data can produce better answers sooner. The diagram can be analyzed in pairs, showing clearly that data from any two is incomplete:

- Their data + outside data ignores what I know.

- My data + their data ignores outside reality.

- My data + outside data ignores what they know.

Empathy tip: When you step into the other's shoes, slip into their head long enough to look out at the world through their eyes. Stay there for fifteen seconds, absorbing what you see. Like most worthwhile endeavors, it takes skill and practice. The payback will amaze you if you work at it. One proven technique was first clarified by Timothy Gallwey in his book The Inner Game of Tennis. After prescribing concentration on the seams of a ball to “create time” to hit the ball, he explains how he continues to concentrate in a match. The problem, not unlike life, is that between points there is an explosion of noise in your head: thoughts about the next point, the last point, what needs to be done at home after the match, who is watching, and so forth. His trick is to focus on his breathing between points! The focus is on observing, not controlling your breathing because you don't need to help your lungs perform. As Timothy Gallwey notes, “When the mind is fastened on the rhythm of breathing, it tends to become relaxed and calm. . . . Anxiety is fear about what may happen in the future. . . . But when your attention is on the here and now, the actions which need to be done in the present have their best chance of being accomplished.”7

Create an environment of higher performance. In addition to common ways of reducing noise—room treatment, white noise, closed-door conference rooms, anti-yelling rules (just made up that last one; who does that?)—empathy between pairs of people can remarkably impact the work environment. And as one of the best restaurant entrepreneurs you've never met says, “It's cheap!”

If you look outside at our world, you'll spot powerful trends that are sneaking under our doors, enveloping all of us who aren't living in a climbing tent on the slope of 22,000-foot-high Mount Aconcagua in the Andes Mountains.

VUCA is a military acronym that, like the Internet, is creeping into our lives. It stands for “volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous,” and it sounds like a familiar descriptor of life around us. What's new is its acceleration. Its nose is well into our tents, creating anxiety (fear) about our futures.

One of the fundamentals of dealing with fear espoused by beefy movie heroes is to move right into it. It's a great principle for everyone else but us, especially me when I'm afraid. The power of empathy, of course, is that it can create pairs who will grapple with fear for each other, and drain its power to dilute their best offerings.

Increasing hope and reducing fear. Robert Johansen in his book Leadership Literacies paints a compelling picture of our future, leaking now into our present, that is a combination of escalating fear and enhanced hope. The VUCA challenge is to boost hope because VUCA will continue, likely with greater intensity.

Here are three paths to boost hope, in Johansen's view:

Seek clarity instead of certainty. The difference is that clarity is expressed in stories, not rules, which embrace the essential nuances of reality in ways that can satisfy the drive for understanding without providing false insights. In his book On Being Certain: Believing You Are Right Even When You Are Not, neuroscientist Robert Burton demonstrates the certainty fallacy: We can feel we're right and be flat wrong. He says, “Certainty and similar states of ‘knowing we know’ arise out of involuntary brain mechanisms that, like love or anger, function independently of reason.”8

Explore voluntary fear engagement. Fear is far more debilitating than we realize when looking over our leadership teams. We are trained to hide feelings about it, to act instead as though we're “fine” amid fearsome possibilities. Most of us partition fear-inducing situations away from our everyday lives and give them an as-if reality. For many years, I windsurfed avidly either on the mile-wide Columbia River or in the ocean off Maui. Rational examination would spark fear in either place: The river offered 200-foot-long tugboats and barges with zero ability to turn or stop. The ocean included both sharks and coral, both capable of skin-shredding pain.

I was afraid every time I stepped into the water. The act of stepping into the water was stepping into the fear, reducing it enough for me to function well enough to get back at the end of the trip.

Johansen and others prescribe regularly stepping into the fear by using games as a safe alternative to BASE jumping or swordplay. There are now games that go beyond shoot to kill, involving worldwide teams and visceral competition. Ergo, fear of losing, a healthy step into personal fear. So yes, I prescribe the most intoxicating competitive game that you can tolerate as part of your executive development program. Why not?

Gaming for grit. The book Grit by Angela Duckworth paints a research-deep picture of the definition and path to enhanced grit. VUCA demands not only resilience—the ability to recover from a hit—but persistence through diversion and difficulty. There are now games of suitable sophistication to seduce executive leaders into competing intensely over time. The grit required to stay in the game will carry over to the “game” of repeatedly leading into VUCA. VUCA promises to be a succession of trips into a dark room, particularly for leaders, where uncertainty and its relatives strain both leadership and continuity. That leadership persistence is a requirement to continually light the fire of hope. It offers some certainty in the uncertainty of VUCA that will infiltrate our work and home lives. That certainty can frame hopeful efforts, recovery, revision, and renewed vitality, which are the foundation of successful pairs, teams, and organizations.

Empathetic Tradition

How you lead impacts your people, but it also impacts their people: their current subordinates, new hires, folks transferred into the department, and the people who they train. Because the sum of daily behaviors of folks around us becomes the environment that we work in, the power of this concept is far beyond occasional kindliness.

The idea of generational transmission of trauma is a suitable model if you replace the word “trauma” with “empathy.” The concept goes back as far as the Bible: “The sins of the fathers will be visited upon the sons.” Or now, children who are beaten are more likely to beat their children, perpetuating a cycle that can wither generations. Remarkably, however, a significant portion of abused children grow up without a trauma hangover, live healthy lives, and do not pass along their pain. Although part of the trauma transmission mechanism is genetic, much of it is not. Further, therapy and training can mitigate the impact of trauma in the life of the victim, as well as reducing the chance that they will pass on their trauma.

What does this have to do with empathy? If empathy is a way toward authentic connection that steps outside rank and power, then it's worth developing as a human being, as well as a leader. Empathy can be learned, or more correctly, natural inclinations can be reinforced through training and by the example of leaders. Bruce Cazenave, CEO of Nautilus, a successful leader in multiple companies, has a way of being immediately present to nearly everyone. It's a powerful experience to have this man asking a personal question about something that he knows that I value—in my case, my car. His knack is to suggest that he's more interested in what the car means to me than in discussing specifications or mechanical high points.

When I asked him in an interview how he came to become such a close student of his people, he described working early in his career for a senior executive at Black & Decker. You guessed it: The Black & Decker guy worked hard to know details about each of his people and asked about them. There's your intergenerational transmission model in action.

Empathy toward yourself. Many leaders I know are unconscious masters, unaware of their techniques or their impact on others. The door to self-observation stays open in most of us for brief bursts, often delivered by a spouse, children, or a disgruntled employee, sad to say. Many leaders I've known have an intellectual understanding of their impact, but few develop the visceral connection that empowers human connection and commitment.

When I was president of a midsize manufacturing firm, I hid the car that I loved for fear that it would prejudice employees against me. Yes, hid it—parked where I thought no employee would find it. It was a midlevel BMW, the best that I could afford, and I loved having it and driving it. I misunderstood my impact on my employees, however. Instead of jealousy about my car and anger toward me (which I feared), I was shocked to look up from my desk one day to see the smiling face of our best machinist. He emigrated to the United States with his family when he was young, and still spoke with a Central European accent. He asked, “Where did you get the snow tires? They don't have studs.” Clearly, he knew exactly where my car was parked, looked at it enough to see that the snow tires replaced the regular tires, and cared deeply about it, in detail (he's a machinist, so no surprise). I soon learned that most of our workers counted that car as “our car” and were so proud to be associated with it that they “counseled me” whenever there was a bump or a mark on it!

ALLOW FOR CHOICE OF PARTNERS

Some pairs work better than others, and thoughtful pairing can improve results, or at least avoid creating problems. For example, when assigning a team to a project, consider including pairs who have shown that they work well together. This seems obvious, but it may produce a stronger team than one chosen for technical ability or experience alone. Even better, ask for volunteers for a team, and arrange the asking to enable folks to see “who's on the team,” so that pairs who work well together can put themselves on the team.

The reverse can also work. A team that doesn't know each other well can be an opportunity for new strong pairs to develop, adding to the potential strength of leadership and project work in the company. It's appealing to think that there's a process for matching pairs, but remind yourself of the mystery of dating and marriage: We're very complex, and simple algorithms probably won't deliver the “click” that strong pairing can. Instead, building a team or a pair for an especially tough project can be a great way for folks to get acquainted— and some strong pairs may emerge because of it!

Most supervision happens in pairs, not in meetings. And supervisors choose a fraction of the folks who report to them (despite their wishes). Over time, supervisors may replace folks who are a bad fit with those who will hopefully be easier to work with, but the questions supervisors face with new relationships almost always include these:

- How do I get the person to tell me the straight stuff?

- How will they let me help them?

- How can we build a relationship that's mostly about each of us bringing what we can to the situation, rather than role-playing or posing, or worse?

Remarkably, building empathy can accelerate development of a relationship that includes all of these, and more. For openers, your empathetic techniques will fail if they're for manipulation or a hidden objective. Even more important, if your goal serves you instead of the company or them, you'll fail in a fog of suspicion. Instead, start by asking for help—genuine help about a real problem that's a challenge for you. If you fold in respect for the other person's skills and ignore their rank in the company, you're off to a good start.

A client, a senior officer in a major corporation, found himself tagged with a company initiative that required tools he didn't have. The corporate vice president of legal and human resources had a budget and links to outside experts, but our hero's relationship with the VP was mixed up with differences in rank and power. When he sat down in the VP's office as a guy asking for help, with nothing to negotiate, he found a man pleased to offer help who confided some of his own fears about the task in front of them. He moved from a suspicious distance to a comfortable pairing built on mutual empathy!

LINKING PAIRS

Linking pairs almost always delivers better results if part of the preparation includes working with each person individually first to clarify their interest and concerns in the proposed pairing. This exercise can be dramatically powered up by using the kindness trio technique, outlined below.9

Use the same techniques with an individual and when joining a pair: First, identify a key person or a pair to lead the effort. Next, set a goal such as increased focus, higher output, fewer errors, and so forth in agreement with the person or pair. Then shift to the kindness trio technique:

Think about a characteristic of this person that you appreciate. Look for something that creates some feelings in you or at least a sense of respect. Use that insight as a doorway to working kindly with the person.

Put down your shield. This is no commune from California; it's an approach borrowed from skilled hostage negotiators. You may think that you and your people are fundamentally different from folks who take hostages, but there is little difference in much of your psychological makeup. So, take advantage of these insights.

Gather data about what's going on in that person's mind (empathy). Empathy is your recognition that the other person's mind is involved and has information that can help you both. It is your job to learn this information and to make it easy for the other person to share. (Warning: If you try to use this to take advantage of the other person, they'll see it and you risk losing their trust for a long, long time.)

Treat that person with deference. Not just respect, but deference. Skip the power politics. Face the fact that this person has something that you want: their skill, attention, motivation, and so forth. Deference means treating them as someone who has power, respect, and a strong place in the world, and you are happy to get to work with them. Your deference will enable the next gentle exploration:

- What are they afraid of losing? What's on the table in this discussion for them, especially things they value that they might be afraid they'd lose? Slow down, inquire for data. You're looking for information, not for an advantage.

- When you see what they fear losing, say it out loud: “It seems like there's more going in than meets the eye here for you. Is that true?”

- Listen closely.

- The point of this approach is to accept the delightful truth that most people have way more to offer than you allow them to provide. The leadership task is to provide two contrasting elements: focus and depth.

You have two primary tasks here:

- Provide a frame for the work. This frame is like a hallway leading to a room. The room is the goal, or what will it look like when we get there; the hallway is the boundary of where to look and what to ask. Framing must be a two-way conversation, both to assure mutual understanding and to find the best possible objective.

- Provide an empathic invitation for them to participate. “Empathic” means that it feels safe to them, freeing them to offer what they have straight up.

When this approach is applied, the immediate effect is often wonder: wonder at the burst of ideas, wonder at their quality, wonder at the speed of movement. It's invigorating enough to convert unfamiliar pairs into folks who can't wait to work together again.