The Project Selection and Value Realization Process

An effective project selection process can set the tone for strategic alignment and value realization. Certain types of projects align with strategy more effectively than others. Some projects are not designed for cash value realization. It’s important to have a framework that will help define both project type and its alignment to strategy so that projects can be prioritized effectively and selected appropriately.

This book is about realizing cash value from your improvement projects. The first step in the process of value realization is selecting and prioritizing projects. Companies have limits—limited budgets, time, people, and limits to the amount of change they can absorb. As a result, companies do not have the luxury of implementing every project that seems interesting or valuable at any time they want. They must choose, and to do so, they will need a prioritization approach.

When dealing with companies of all sizes, from start-ups to some of the largest and most successful companies in the world, rarely have I seen an effective approach that allows leaders to prioritize a portfolio of improvement opportunities or projects based on two key criteria; strategic relevance and the ability to achieve desired cash value from the project based on project type.

Oftentimes, a process may be broken, so there is an improvement project designed to fix it. There may be an area that may be considered high cost by consultants and subsequently deemed in need of improvement. Sometimes, a company thinks something is wrong and may not be sure exactly what it is, so they need to figure out what is wrong and how to fix it. In each of these cases, the project is often considered in the context of the extent to which the process is perceived as being broken, and the value associated with fixing it, but not necessarily in terms of the type of project being considered and its strategic relevance.

This is a problem. According to Peter Keen, author of The Process Edge, “firms have invested in processes that were not critical to their success. Processes were improved, sometimes dramatically, but they were not the salient ones. Key processes went on unexamined, some even suffering from the attention given to less important ones, so the change program succeeded but the firm succumbed.”1 Leaders need an objective way to identify and prioritize those processes that are strategically important to the company and its cash generation potential while also allowing leaders to compare and prioritize project options based on these factors.

One approach involves creating a Project Prioritization Matrix that considers both salience and project type. This matrix is a hybrid that comes from two sources: Peter Keen’s Salience Worth Matrix from The Process Edge2 and sage advice offered early in my career.3 The Project Prioritization Matrix, pictured in Table 5.1, creates a built-in prioritization schema that helps determine which projects should be approved and in what order based on salience and anticipated cash returns. Let’s look at the two axes on the matrix.

Table 5.1 The Project Prioritization Matrix helps categorize projects based on the salience of the process being improved and the type of project being purchased

Informational | Instructional | Implement | |

Identity | |||

Priority | |||

Background | |||

Mandated |

In his book, the Process Edge, Peter Keen creates an intriguing model that focuses on the notion of process salience or visibility. According to Keen,

The word salience suggests standing out from the general surface, being prominent; salient processes are the most prominent ones. They are the processes that relate most directly to the firm’s identity—those that visibly differentiate it from its competitors—and the priority activities that keep the engine of everyday competitive performance running.4

The idea is that processes that are more salient in the eyes of customers or the market may have a greater strategic importance or value to your company. However, part of the issue is, companies often do not take salience into consideration when considering improvement projects, so opportunities to enhance this relationship are often lost.

Keen defines four types of processes: identity, priority, background, and mandated in order of salience.5

Identity processes define a company to itself, its customers, and its investors. For FedEx, Keen mentioned, it’s their reliability. The process of delivering packages to our home or work is what we largely know them for. The delivery process is likely the most salient process to their customer base: those who engage them and pay the bills. For McDonalds, it’s their speedy consistent food preparation and their loyalty.6

Priority processes are “the engine of corporate effectiveness” and they provide the greatest level of support to the company and its identity processes. For instance, with FedEx, priority processes might include information technology and the ability to track packages on a real-time basis, the route planning process that maximizes coverage while minimizing fuel cost and travel times, and the logistics network of trucks and airplanes that help ensure the packages get to the warehouses before they go out for delivery. These are processes that are important when delivering the reliability we expect, but they, themselves, are not what FedEx is known for. For McDonalds, it may be food supply management, as McDonalds is a restaurant not a food distributor.7 However, the food supply management process helps enable the consistency the market looks for. The idea behind priority processes is, if they fail, the identity processes, too, may fail. Hence, there is an elevated importance that priority processes have over the next type of process, background processes.

Background processes are the other processes that enable a business to operate effectively. For the most part, they are the processes that are not identity or priority. For FedEx and McDonalds, for instance, accounts payable or payroll may be background processes. This isn’t to suggest they aren’t important processes. On the contrary, they are very important. However, neither payables nor payroll defines either company. They are critical processes that needs to operate effectively.

A natural inclination is to identify types of processes automatically as being an identity, priority, or background process. This isn’t the case. HR may be a background process for a hospital, but for a consulting firm or a company that offers staffing services, HR may be a priority process. Each determination should be aligned with the company’s strategy, brand, and offerings rather than generically assigning categories to processes.

The fourth type of process is a mandated process. Mandated processes are either those that are required by the government, are required to meet government rules and regulations such as taxes and reporting, and those required by clients or other agencies. These processes are directly tied to some sort of compliance issue, contract, or other requirement. The key here is, the process is a requirement and needs attention. Where it falls on the prioritization scale is likely best considered on a situation-by-situation basis. Considerations should include the importance of inaction (nothing, fine, or imprisonment), and, hence, the penalties for noncompliance should be salient in the assessment itself.

The next axis focuses on the type of projects that are being considered. Early in my career, someone told me people buy or execute three types of projects:

• Informational

• Instructional

• Implementation

Informational

Informational projects focus on providing information about a problem the company may be facing. Often, this involves strategic or tactical situations where the company is trying to understand whether there is an issue, what to do about it, and to gain guidance about the impact of fixing it, or not. Common among informational projects is assessments, risk analyses, and strategy design sessions. Key for these engagements is to highlight performance challenges and issues and recommend a course of action. What you have at the end of this type of an engagement is often a presentation of facts, figures, findings, recommendations, and sometimes anecdotes that help explain what is going on, why, what the company should do, and the expected outcome as a result of following the recommendations.

Instructional

There will be a point where companies know what they need to do. They understand they need to reduce costs, for instance, but how? They know they need to offer new, or cut existing products or services, or to create a new division. How should they move forward? What’s the plan?

Instructional projects focus on instructing the company how to move forward by creating a plan to address the issues found in the informational projects. Included in this should be the scope of the project, objectives, high level-to-detailed level project plan, expected benefits and costs when reasonable to estimate them, and ideally, a governance plan to ensure tasks are carried out to achieve the projected benefits.

Until this point, we have gotten information; we know what is wrong and we have a plan to execute so that we can improve our performance. Information and instruction are valuable, of course, but their value is limited to their ability to be implemented.

Implementation

Implementation involves executing the plan described in the output from an instructional project. This means buying and implementing the software, hiring three new salespeople, implementing lean, or shutting down the division. This is where the rubber meets the road. Promised efficiency improvements will not happen completely without implementing the software that enables them. Sales increases will not happen without adding the extra staff that will pound the pavement to create opportunities with new or existing customers.

The idea is, when it comes to the prioritization of projects in the context of creating cash value, one would generally prefer projects that involve implementation over providing information or instruction. Informational and instructional projects have no financial value to them on their own. The purpose they serve is tied to the promise of savings, both positive and negative, that will result from implementation. If the promise of savings is positive and it makes sense to move ahead, the information has been valuable. However, if the savings potential is negative, knowing this, too, is positive.

The Project Prioritization Matrix allows you to plot each project opportunity based on salience and project type and use this as a basis for prioritizing your project portfolio.

Interpreting the Chart

There is no single way to assess or interpret the data from the chart. Much of it is a function of where you are as a company. Consider project type. The initial thought might be that implementation projects are the most important and, therefore, should have priority over others. However, this may not always be the case. There are three factors I’ve seen that influence the general prioritization schema or approach:

1. Where is the company in terms of need?

2. What is the lead time to value realization?

3. What is the size of the opportunity?

Where Is the Company?

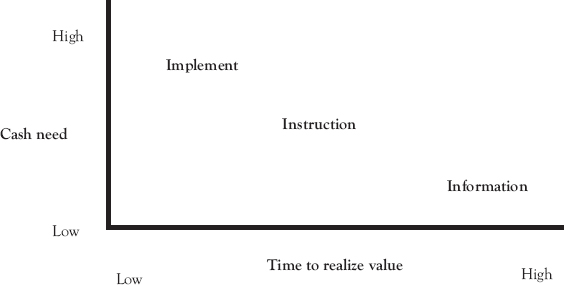

The ebb and flow of corporate performance practically guarantees seasons. There are seasons the company needs to focus on cash generation and seasons where it can invest money in strategic opportunities. It’s important to assess where you are as a firm and to use that as a basis for prioritization. In Figure 5.1, we can see how this may play out.

Figure 5.1 By mapping the time to realize value and the need for cash, companies can get guidance regarding the type of project they should look to implement

Companies in need of quick cash may give Implement projects the highest priority because they may be the fastest path to cash. Second would be Instruction because it creates a plan that positions the company to be one step away from a project that can be fully implemented. The lowest priority may be Insight, where there is a much further lapse between when the recommendations are made, and the program creates cash value.

The opposite of this is the scenario where the company is in a good cash position and can look to make investments in the future. This situation, from my experience, is seen more frequently with private companies where there is little to no pressure from shorter term investors. Private owners may be in a position to make decisions for the future by taking a step back, asking questions, and seeking solutions to opportunities that will lay the groundwork for future performance.

The third scenario is when a company should act to improve its cash position in the medium term. In that context, focusing on laying out plans will set up future opportunities that can, too, lead to implementation when the timing is right. It is almost a lock and load scenario where, when the company is ready to move, it has project opportunities identified and justified, and all that is left is to pull the trigger and implement the chosen opportunities.

Once the company scenario is established and agreed upon, the suggestion is that the leadership should stick to that as a basis for comparison for a period of time. The reason is, if you change too frequently, the prioritization scheme, too, will change, leaving the company in a position where decisions become challenging because the basis for making the decision and the criteria used are shifting.

Lead Time to Value

The lead time to value factor is one that should strongly be considered when selecting projects. The amount of time to implement a project may be enough of an impetus to choose an Instruction project over an Implement project. For example, as mentioned in Chapter 2, I was once a part of a strategy project where the initial returns were substantial as projected, but the project cash payback was 72 months. This was not acceptable to our customer, so we had to redesign the project so that we could reduce the lead time to value. We subsequently broke down the single project into a series of projects that were basically self-funding.

If it takes 36 months from now to realize the financial value with an Implementation project, but an Instruction project can realize a reasonable amount of value in 18 months, the Instruction project may be the right direction to go with all things being equal and if the company is in a position where it needs cash.

One factor to consider in situations like this is to provide, when possible, a pathway to value for the Informational and Instructional opportunities. This pathway includes the value opportunity, the time and effort to realize value, and the potential risks. A savvy manager knows precision isn’t an option at this stage and that the actual value projection, alone, will not be extraordinarily useful due to the numerous uncertainties that exist between identifying a potential opportunity, establishing the plan, and actually executing the plan. In cases like this, I’ve actually found it more valuable to come up with a best- and worst-case scenario to create boundaries for the estimate. With each, you document the assumptions that determine the upper and lower limits of what is possible. We can then discuss the assumptions to assess the plausibility, and to create a level of trust in the projections.

Size of the Opportunity

Finally, opportunity size and type should be important considerations as well. In general, projects with the greatest returns should be given priority, again, all things being equal. The key, however, is in the proper documentation and consideration of cash value. As mentioned in Chapter 2, and as we will see in the next two chapters, project value can be inflated when noncash costs, costNC, are added to cash costs, costC, creating a large number with currency as its unit of measure as we saw with Oracle. There is a way to keep this from happening.

One recommendation is to articulate capacity and cash improvements separately. We will find, creating BCC Models with capacity maps, that most improvement projects begin by improving capacity use. Capacity improvement refers to the amount of capacity saved or that will not be used as a result of the improvement. For instance, increasing efficiency leads to either less capacity consumed to create output, or for the same consumption of capacity, one can create more output. As an example, improvements may either allow someone to perform 10 tasks in 30 versus 60 minutes, or they can now perform 20 tasks versus 10 tasks in the same time. It is the improvement in capacity use that, in most cases, enables steps that lead to cash savings.

Cash improvement will be tied to the rate of cashIN and cashOUT, which are affected by how much capacity is purchased and how much output is sold and paid for. One does not directly lead to the other. In the example above, doing things more efficiently doesn’t mean the company is spending less on capacity. Hence, there is an improvement to capacity use but not to cashOUT. This will help leaders understand where the improvement was made, whether there was a direct cash impact, and if not, what options exist to improve cash as a result of the improvements in capacity use.

As discussed later in the book, documenting capacity savings first is the preferred method. The numbers or values we use to calculate capacity and cash improvements, of course, are raw, unprocessed data, meaning there are no accounting dollar values tied to the opportunity. If we lease 7,500 square feet, for example, and 1,500 square feet is organized for use, we can see we now have an additional 20 percent of space available for use. If we have 5,000 square feet being used for offices, and our space utilization went from 86.7 percent down to 67 percent, we know that one-third or 1,700 square feet will be available for other use. Compare this to suggesting you’ve saved $2,375 in capacity costs. What does that mean from practical or managerial perspectives? Additionally, it’s a costNC value anyway, so it’s of no cash value. Your lease will not go down because you use space more efficiently. Of course, without knowing where the number came from, you can’t back into how much actual capacity you can now use for something else. The average person would not be able to convert the $2,375 into how much space was saved, or how much is available for use without a good amount of context. The capacity-based approach also allows for relative improvement sizes to be compared easily across projects with no ambiguity and no false financial savings.

When considering the cash savings and the size of the opportunity, we have to think about how the improvement will affect cashIN and cashOUT.

The next two chapters will explain in much more detail how we do this, but the cash calculation and the requisite management actions necessary to achieve the cash benefits should be the determining factors regarding how large the cash opportunity truly is.

Some will still find the need to put a dollar value on capacity savings. This is highly discouraged, but if required, the suggestion is A. The technique for calculating value should remain consistent and, B. The value is not combined with cash savings to create a total dollar savings. The values are different, as one is cash and the other is not. Hence, adding them together makes no mathematical sense and can compromise managerial decision making.

Next chapter, we will discuss how improvement projects create value for organizations.

Key Takeaways

1. When considering improvement projects, strategic alignment is important. Each project should be assessed on its salience.

2. The type of project, too, is important. Informational and Instructional projects will not lead to cash value on their own. This does not mean they are not important. It just means if the company seeks cash returns, the only way to achieve them is through Implementation projects.

3. Companies should have a standard way to prioritize projects. The recommendation here is to do so by using the Project Prioritization Matrix, which both aligns the improvement opportunity with the company’s strategy and considers the cash generation potential of the opportunity.

4. The Project Prioritization Matrix should be a first step and not an end-all, be-all for decision making. Other factors such as the time to value, and opportunity potential should be considered.

1 P.G.W. Keen. 1997. The Process Edge: Creating Value Where It Counts, 16. Harvard Business Review Press.

2 Ibid.

3 Do not know the source, unfortunately.

4 Ibid, 16.

5 Ibid, 26.

6 Ibid.

7 Ibid.